The molecular design concept and mechanism leading to highly efficient thermally activated delayed fluorescence are presented.

Keywords: Organic light-emitting diodes, Thermally activated delayed fluorescence, Reverse intersystem crossing, Excited-state dynamics, Transient absorption spectroscopy, Charge resonance state

Abstract

The design of organic compounds with nearly no gap between the first excited singlet (S1) and triplet (T1) states has been demonstrated to result in an efficient spin-flip transition from the T1 to S1 state, that is, reverse intersystem crossing (RISC), and facilitate light emission as thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF). However, many TADF molecules have shown that a relatively appreciable energy difference between the S1 and T1 states (~0.2 eV) could also result in a high RISC rate. We revealed from a comprehensive study of optical properties of TADF molecules that the formation of delocalized states is the key to efficient RISC and identified a chemical template for these materials. In addition, simple structural confinement further enhances RISC by suppressing structural relaxation in the triplet states. Our findings aid in designing advanced organic molecules with a high rate of RISC and, thus, achieving the maximum theoretical electroluminescence efficiency in organic light-emitting diodes.

INTRODUCTION

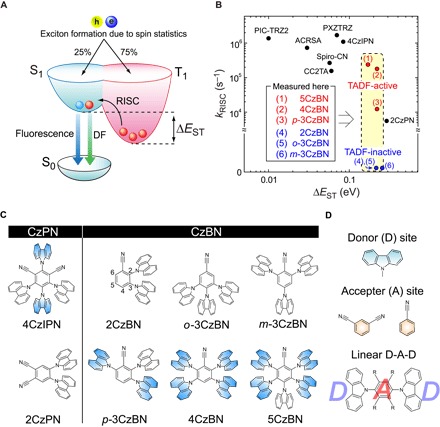

One of the most effective ways to enhance internal electroluminescence (EL) quantum efficiency (ηint) in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) is well recognized to be the management of the pathways between excited singlet (S) and triplet (T) states. In OLEDs, the effective use of triplets is fundamental for achieving high ηint because one singlet is generated for every three triplets based on spin statistics under electrical excitation (Fig. 1A) (1). Although a spin-flip from pure S to pure T states, that is, intersystem crossing (ISC), is generally forbidden because of their different spin multiplicities, it becomes possible when their wave functions are mixed through spin-orbital coupling (SOC). The degree of mixing (λ) can be simply expressed as λ = HSO/ΔEST, where HSO and ΔEST are the SOC constant and energy difference between the S1 and T1 states, respectively (2). By incorporating a heavy atom such as iridium into organic molecules, HSO is enhanced and a strong mixing of the spin orbitals of the S and T states is induced, resulting in efficient radiative decay from T1 to the ground state (S0), that is, phosphorescence, with nearly 100% of photoluminescence (PL) quantum yield (PLQY) (3).

Fig. 1. EL mechanism.

(A) Schematic of electrical exciton generation and EL mechanism in TADF-OLEDs. (B) Relationship between experimentally determined kRISC and ΔEST in previous works (5, 13–19) and this work. The kRISC values of (4) to (6), treating to ~0 s−1, are below the limit of the estimation because of nearly no or undetectably weak DF intensity (Fig. 2A, inset). (C) Molecular structures of CzPN and CzBN derivatives, highlighting linearly positioned Cz moieties (blue). The numbering of the substituent positions of the BN core is depicted for 2CzBN. (D) D and A units of the CzPN and CzBN derivatives and D-A-D structure constructed with a linearly positioned Cz pair. R indicates substituents with electron-accepting properties, such as cyano groups.

Alternatively, the λ can be enhanced by decreasing ΔEST, which can also open a pathway from lower-energy T1 to higher-energy S1, that is, reverse ISC (RISC), when ΔEST is small enough. On the basis of quantum chemical theory, ΔEST is proportional to the exchange energy, which is related to the overlap integral between the two open-shell orbitals responsible for the isoconfigurational S and T states, and is typically ~1 eV for conventional condensed polycyclic aromatic compounds, such as anthracene (4). Because the HSO of aromatic compounds is also small, RISC is generally negligible. However, when the ΔEST approaches the thermal energy (~26 meV at room temperature), RISC is induced via thermal excitation, and delayed fluorescence (DF) is subsequently emitted from S1. This is so-called thermally activated DF (TADF), and recent extensive studies on TADF-OLEDs have revealed ηint values of nearly 100% (5–11). According to the semiclassical model of TADF, the rate constant for RISC (kRISC) is given by kRISC ~ A × exp(−ΔEST/kBT), where A is the pre-exponential factor including HSO, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the temperature (12). Therefore, a high kRISC can be achieved by decreasing ΔEST. However, although this idea has been supported by many experimental results, as shown in Fig. 1B (5, 13–19), several papers report fairly high kRISC values even for large ΔEST of a few hundred millielectron volts (6, 20). For instance, carbazol-benzonitrile (CzBN) derivatives synthesized by Zhang et al. (20, 21) were reported to have a ΔEST of ~0.2 eV. Although the ΔEST is too large for efficient RISC at room temperature, CzBN-based OLEDs showed high external EL quantum efficiencies (ηEQE) of ~20%. This ηEQE value means that, under an assumption of a light outcoupling efficiency of OLEDs (22), all the excitons generated electrically were used for EL.

A number of fundamental studies using transient PL (TR-PL) spectroscopy and theoretical calculations have been devoted to understand the mechanism of efficient RISC upon a large ΔEST of several hundred millielectron volts (6, 23–27). In particular, Dias et al. (25) and Gibson et al. (27) have proposed that the second-order SOC involving the locally excited T state (3LE) and charge-transfer (CT) excited T state (3CT) in thermal equilibrium is crucial for efficient RISC. In the scenario, the spin-allowed transition of 3LE to CT excited S state (1CT) in materials having a large ΔEST is facilitated efficiently by the vibronic coupling between the 3LE and 3CT states (25, 27). This suggests that RISC is a dynamical process in an excited state. However, this study has been thoroughly conducted for only a few molecules, which consist of a near-orthogonal electron donor (D) and acceptor (A) units. Still, a deeper understanding of the mechanism leading to efficient RISC based on a direct observation of excited states formed in both the S and T states is needed to clarify the relationship to the chemical structure and will provide a strategy for the advanced molecular design of TADF molecules.

Here, we used a comprehensive set of complementary experimental techniques, with an emphasis on transient absorption spectroscopy (TAS), to demonstrate that kRISC cannot be determined by the ΔEST alone and strongly relies on the excited states. To understand the mechanism, we focused on Cz-phthalonitrile (CzPN) (5) and CzBN (20, 21) derivatives: 4CzIPN, 2CzPN, 2CzBN, o-3CzBN, m-3CzBN, p-3CzBN, 4CzBN, and 5CzBN (Fig. 1C). Unlike the CzPN derivatives reported previously by our group (5, 19), CzBN derivatives have similar ΔEST values (~0.2 ± 0.04 eV) (see Table 1). In this sense, similar kRISC values might be expected for CzBN derivatives, but the result is completely different. By looking at excited-state dynamics using TAS, we are able to attribute the different kRISC to the formation of delocalized excited states, which facilitates RISC. We also identify that a linearly positioned Cz pair in a D-A-D structure (Fig. 1D) is the structural requirement for the formation of delocalized excited state. Our findings provide an advanced general design for TADF molecules with high kRISC and facilitate the deeper understanding of significant spin up-conversion processes (2).

Table 1. PL characteristics and rate constants of CzBN and CzPN derivatives in solution and doped film.

| Material |

ΦPL Air* (%) |

ΦPL Degassed* (%) |

ΦPL Solid film† (%) |

τprompt‡ (ns) |

τDF‡ (μs) |

‡§ (×107 s−1) |

kRISC‡§ (×105 s−1) |

kISC‡§ (×108 s−1) |

‡§ (×104 s−1) |

ΔEST‡║ (eV) |

| 2CzBN | 15 | 23 | — | 10.9 | 1.3¶ | 1.4 | 0 | 0.8 | 78.3 | 0.21 |

| o-3CzBN | 21 | 31 | 26/33 | 18.5 | 15¶ | 1.1 | 0 | 0.4 | 6.5 | 0.21 |

| m-3CzBN | 15 | 17 | 33/26 | 3.6 | 39¶ | 4.2 | 0 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 0.24 |

| p-3CzBN | 10 | 14 | 35/31 | 1.2 | 35 | 8.3 | 0.12 | 7.5 | 2.7 | 0.22 |

| 4CzBN | 9 | 62 | 94/76 | 1.6 | 36 | 5.6 | 1.8 | 5.7 | 1.7 | 0.22 |

| 5CzBN | 9 | 85 | 89/78 | 3.8 | 39 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0.42 | 0.17 |

| 2CzPN | 42.3 | 46.5 | 89** | 27 | 28¶ | 1.6 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 3.6 | 0.21 |

| 4CzIPN | 10 | 94 | 82** | 16 | 4.6 | 0.63 | 20.3 | 0.56 | 1.5 | 0.04 |

*PLQY at a concentration of 10−4 M in toluene.

†PLQY for PPT host matrix doped with 3 wt % (left) or 15 wt % (right) of the emitter.

‡Solution samples.

§Rate constant of radiative decay of singlets , , kRISC, and kISC of the solution samples determined by the method described by Masui et al. (18).

║Energy gap calculated from S1 and T1 energy levels estimated from the threshold of fluorescence spectra and peak (2CzBN) or threshold (others) of phosphorescence spectra (Fig. 2B), respectively. The error is ±0.03 eV. The data of fluorescence and phosphorescence spectra of 2CzPN and 4CzIPN are depicted in fig. S7.

¶Virtual values as determined by measuring a time profile of decay curve of triplet state absorption bands in microsecond-TAS (see figs. S1 and S8).

**Value of 2CzPN-mCP [1,3-bis(N-carbazolyl)benzene] (6 wt %) by Masui et al. (18) and of 4CzIPN-CBP (4,4-N,N′-dicarbazole-biphenyl) (6 wt %) by Uoyama et al. (5).

RESULTS

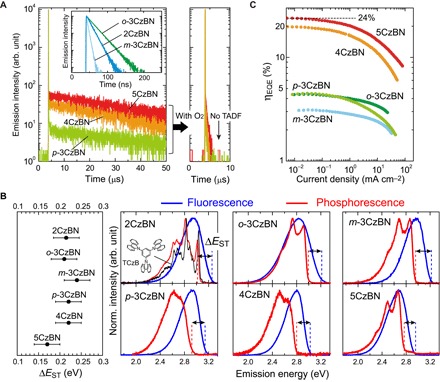

Before examining the excited-state dynamics, we evaluated the fundamental photophysical properties of the CzBN derivatives (Table 1). TR-PL profiles of the CzBN derivatives in oxygen-free toluene show strong DF for 4CzBN and 5CzBN and weak DF for p-3CzBN, but no DF for 2CzBN, o-3CzBN, or m-3CzBN (Fig. 2A). The observed DF completely vanished in the presence of oxygen, indicating that the DF is emitted via T states. In Table 1, the kRISC values of 4CzBN (1.8 × 105 s−1) and 5CzBN (2.4 × 105 s−1) are larger than the kRISC value of p-3CzBN (0.12 × 105 s−1) by one order of magnitude despite similar ΔEST values of ~0.20 eV for the three materials (Fig. 2B). Moreover, although the ΔEST of o-3CzBN is almost the same as that of 4CzBN, o-3CzBN showed no appreciable DF, that is, kRISC ~ 0 s−1. The rate constants for nonradiative decay of the triplet states , a competing parameter of kRISC, are of the same order of magnitude for the three 3CzBN isomers, ~ 104 s−1, although their kRISC values differ by four orders of magnitude (Table 1). This result indicates that the TADF is activated by the large kRISC and not because of the suppression of the nonradiative decay path of the triplet states.

Fig. 2. Photophysical characteristics.

(A) PL decay curves of 2CzBN, o-3CzBN, m-3CzBN, p-3CzBN, 4CzBN, and 5CzBN in toluene at 295 K. 2CzBN, o-3CzBN, and m-3CzBN showed only prompt fluorescence, whereas p-3CzBN, 4CzBN, and 5CzBN exhibited prompt and delayed fluorescence (TADF). Right: Disappearance of TADF due to deactivation of T states caused by O2. (B) ΔEST with an error of ±0.03 eV of CzBN derivatives, estimated from the threshold energy difference between the fluorescence and phosphorescence spectra (77 K) for each molecule (right). Note that only the energy of the phosphorescence spectrum of 2CzBN was chosen from a first peak top (0-0 peak). For 2CzBN, the phosphorescence spectrum of TCzB (black) is also shown to display the spectral similarities with 2CzBN. Inset: Chemical structure of TCzB. (C) ηEQE as a function of current density for OLEDs [ITO/TAPC (35 nm)/mCP (10 nm)/dopant (15 wt %):PPT (30 nm)/PPT (40 nm)/LiF (0.8 nm)/Al (100 nm)] containing o-3CzBN (green), m-3CzBN (light blue), p-3CzBN (light green), 4CzBN (light brown), and 5CzBN (red) as the emitter dopant.

When doped at a concentration of 15 weight % (wt %) in a 2,8-bis(diphenylphosphoryl)dibenzo[b,d]thiophene (PPT) matrix, 5CzBN showed a PLQY of 78 ± 2%, and OLEDs using 5CzBN reached an ηEQE of ~24% (Fig. 2C), indicating that 5CzBN can intrinsically harvest almost all excitons for light emission in the OLEDs with the help of RISC. Here, we note that the 15 wt % 4CzBN–doped PPT films show a PLQY comparable with that of 5CzBN. However, the ηEQE of the 4CzBN-based OLEDs showed a slightly lower value of ~20%, presumably because of a lower charge carrier balance in the devices. Although 15 wt % p-3CzBN–doped PPT films show a low PLQY of 31 ± 2%, the ηEQE of p-3CzBN–based OLEDs (~4.5%) is much higher than the theoretical limit of ηEQE for ordinary fluorescent OLEDs considering a similar PLQY (1.6 to 2.3%), where a light outcoupling efficiency of 20 to 30% and an exciton generation ratio of singlets of 25% are assumed (22), indicating that TADF from p-3CzBN contributes to ηEQE. These photophysical properties and OLED characteristics imply that kRISC cannot be predicted by ΔEST only, and instead, the bonding configuration of D to A moieties plays an essential role for the CzBN derivatives to increase kRISC and enhance ηEQE.

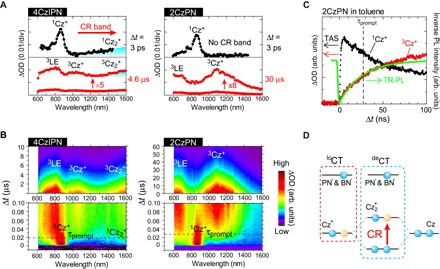

To understand the large difference in kRISC by the structural modifications, we investigated the excited-state dynamics of CzPN and CzBN derivatives using TAS (28–30). We measured the absorption change (ΔOD; OD, optical density) caused by the presence of photoexcited states of not only S1 and T1 but also intermediate excited states as a function of delay time (Δt). Figure 3A shows the TAS spectra of 4CzIPN (Δt = 3 ps and 4.6 μs) and 2CzPN (Δt = 3 ps and 30 μs) in toluene. The TAS profiles over the full measured range of Δt are illustrated in Fig. 3B as contour maps. The contour maps of both molecules show that the TAS spectra change in the vicinity of ISC, as judged from the time constant of the prompt fluorescence (τprompt) determined by TR-PL (Fig. 3C). We found that the spectral shape for Δt > τprompt stays unchanged for each molecule because of the almost identical decay lifetimes of T features (fig. S1) (the assignment is described below). In addition, we confirmed that the lifetimes of the T features for 4CzIPN are nearly the same as the τDF determined by TR-PL (fig. S1). These results indicate that the observed T states are mutually coupled in thermal equilibrium, and facilitate the RISC as a unit for the dynamics of RISC. Therefore, in the following experiments, we focused on the assignment of the excited states of the S and T states (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. Excited-state dynamics of CzPN derivatives.

(A) Selected TAS spectra of 4CzIPN (Δt = 3 ps and 4.6 μs) and 2CzPN (Δt = 3 ps and 30 μs). div, division. (B) Contour maps of TAS results of 4CzIPN and 2CzPN obtained by different TAS techniques: microsecond-TAS (top) and nanosecond-TAS (bottom) (29, 30). For (B), ΔOD (color intensity) in each figure is normalized arbitrarily for better visualization. (C) Time profile of TR-PL and ΔOD in TAS results at 860 nm (1Cz+) and 1070 nm (3Cz+) of 2CzPN. The TR-PL shown to overlap with the profile of T feature (3Cz+) illustrates the coincidence of their τ. (D) Schematic explanation of the CR band formed by Cz2+ in terms of energy-level diagram.

In the time range of Δt = 3 ps, an intense feature at 860 nm with a small shoulder (760 nm), which greatly resembles features commonly observed for cationic mono-Cz (Cz+) compounds (31, 32), was observed for both molecules. Considering that the absorption spectra of 4CzIPN and 2CzPN showed CT characters (5), we assigned the characteristic features at Δt = 3 ps to the absorption of Cz+ moieties (1Cz+) formed in the S1 state by the photoinduced intramolecular CT transitions (figs. S2 and S3). At the same Δt, we found another band in the near-infrared region of 4CzIPN. This band is a so-called charge resonance (CR) band (31) or an intervalence CT band (32), and it indicates the formation of a delocalized CT (deCT) state attributed to an intramolecular dimeric radical Cz (Cz2+) formed by an electronic coupling between a mono-Cz+ and a neutral Cz moiety (Fig. 3D). Specifically, a deCT state means that the cation charge of Cz+ is delocalized in the Cz2+, whereas the counter anion charge is localized at the acceptor moiety, that is, IPN− for 4CzIPN. The CR band is seen not only in the S1 state as 1Cz2+ but also in the T1 state (Δt = 4.6 μs) as 3Cz2+, together with other rising features at 680 and 1070 nm. These rising features were also observed for 2CzPN in the time range of Δt = 30 μs, but the CR band was not detected. These results indicate that, in the S1 and T1 states, 2CzPN forms a localized CT (loCT) state, whereas 4CzIPN forms both deCT and loCT states in thermal equilibrium. The formation of this delocalized excited T state is consistent with the excited-state scheme for 4CzIPN obtained by time-resolved electron paramagnetic resonance conducted at 77 K (33).

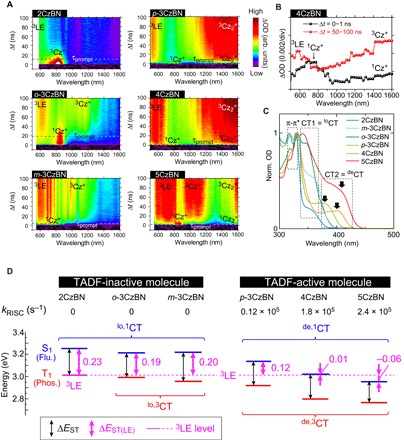

Figure 4A shows contour maps for the TAS results of all six CzBN derivatives in toluene. The TAS spectra at Δt in the vicinity of τprompt of all the derivatives are depicted in fig. S4. In Fig. 4A, 2CzBN shows an absorption band at around 815 nm, which is assigned to 1Cz+ and thus lo,1CT. After transition through ISC, we found only one T absorption band at around 600 nm. Because the phosphorescence spectrum of 2CzBN (Fig. 2B), with clear vibronic progressions and a long triplet lifetime of ~5 s, was in good agreement with that of tricarbazolyl benzene (TCzB; inset in Fig. 2B), the T1 state of 2CzBN is considered to be the same as that of TCzB and, thereby, is assigned to a localized state on a mono-Cz moiety with pure π-π* character (34). In this context, the T1 absorption band at around 600 nm can be ascribed to the π-π* transition of a neutral mono-Cz state (3LE).

Fig. 4. RISC mechanism of TADF-active molecules.

(A) Contour maps of nanosecond-TAS results of 2CzBN, o-3CzBN, m-3CzBN, p-3CzBN, 4CzBN, and 5CzBN in toluene. (B) TAS spectra of the S (Δt = 0 to 1 ns) and T (Δt = 50 to 100 ns) states of 4CzBN. ΔOD is averaged one in each time range. (C) Ground-state absorption spectra of the CzBN derivatives in toluene. (D) Relation between kRISC and ΔEST(LE) of TADF-inactive (left) and TADF-active (right) molecules in energy-level diagram, respectively. Flu., fluorescence; Phos., phosphorescence.

Similar to 2CzBN, the TAS spectra of o-3CzBN show a 1Cz+ band at around 850 nm before ISC and a 3LE band at around 600 nm after ISC. In addition, o-3CzBN exhibited another T band at around 1150 nm. Because the T1 character of o-3CzBN is understood as a mixing of the CT and LE states based on the vibronic-less phosphorescence spectrum (Fig. 2B) with a short lifetime (~1 s) (34), the feature at around 1150 nm can be attributed to the absorption of the loCT state of 3Cz+ (lo,3CT). These spectral characteristics are also observed for m-3CzBN, implying the formation of the same excited states.

Finally, we look at the dynamics of TADF-active CzBN derivatives. Clear 1Cz2+ and 3Cz2+ bands were observed in addition to 1Cz+, 3LE, and 3Cz+ bands for 5CzBN, similar to 4CzIPN, indicating the formation of lo,1CT and de,1CT in the S1 state and 3LE, lo,3CT, and de,3CT in the T1 state, respectively. On the other hand, for 4CzBN, 1Cz+ and 1Cz2+ bands were observed in the S1 state, but no 3Cz+ band was seen after relaxation via ISC and only 3LE and strong 3Cz2+ bands were formed (see also Fig. 4B). The phosphorescence spectra of 4CzBN and p-3CzBN show rather vibronic-less features resembling their fluorescence spectra (see Fig. 2B), indicating a strong CT character in the T1 state (34) because of the formation of de,3CT state. For p-3CzBN, the TAS spectra were essentially the same as those of 4CzBN, except for the energy positions, suggesting a similar T1 character and RISC process as for 4CzBN.

The formation of the deCT state is also reflected in the electronic structure of the CzBN derivatives. In the ground-state absorption spectra (Fig. 4C) of p-3CzBN, 4CzBN, and 5CzBN, a characteristic CT band is observed as the lowest energy transition (CT2), which differs from the commonly observed CT band (CT1) and π-π* band of Cz moieties. Furthermore, CT1 forms for all the CzBN derivatives, except p-3CzBN and 4CzBN. From these results, we can assign CT1 and CT2 to originate from the formation of loCT and deCT characters, respectively. This assignment is consistent with the TAS results, which suggest that p-3CzBN, 4CzBN, and 5CzBN form a de,1CT state in the S1 state, whereas other CzBN derivatives exhibit a lo,1CT state. The same consideration is applicable to 4CzIPN and 2CzPN (Fig. 3B and fig. S2).

DISCUSSION

The combined results of all structural, photophysical, excited-state, and OLED studies provide a comprehensive answer to the question of why kRISC of the CzBN derivatives does not necessarily depend on ΔEST. Molecules exhibiting TADF showed deCT states (that is, 1Cz2+ and 3Cz2+) and a 3LE state, whereas TADF-inactive molecules exhibited only a 3LE state or a combination of 3LE state and loCT states (that is, 1Cz+ and 3Cz+). This indicates, for CzBN derivatives, that neither the presence of only a 3LE state nor a combination of 3LE and loCT states is a sufficient condition for the activation of TADF, and instead, the presence of a deCT state is the key factor for increasing kRISC: The deCT facilitates RISC irrespective of ΔEST. However, this does not exclude the contribution of the combination of loCT and 3LE states to kRISC as 2CzPN, which showed these two states (Fig. 3B) has been reported to exhibit weak TADF (4.2 percentage point contribution to a total PLQY of 46%) (18). This result suggests that a combination of loCT and 3LE states can also be essentially involved in the RISC process if a D unit is combined with a strong A unit, such as PN. That is, the stabilization of the CT state is an important factor for enhancing kRISC.

Now, the practically relevant question is what are the structural requirements for deCT formation? The TAS results of the CzBN derivatives demonstrated that the position of the Cz units connected to the BN core is important. Namely, the positioning of Cz moieties at 2 and 3 (2CzBN) or 2, 4, and 6 (m-3CzBN) cannot satisfy the structural requirement (see Fig. 1C). Although the Cz at the 4-position of o-3CzBN might be expected to tend to form Cz+ because of the low electron density, the TAS results showed that the Cz at the 4-position does not form a CR band with the neighboring Cz moieties at the 3- or 5-position. In addition, we confirmed that the Cz at the 2-position does not play a role in the CR band of p-3CzBN because movement of the Cz from 2- to 4-position in p-3CzBN also showed the CR band (fig. S5). Consequently, we identify the common structure among the TADF-active molecules as a pair of Cz units connected linearly with a bridging A unit, that is, at 2- and 5-positions or 3- and 6-positions (Fig. 1D). This structural scheme is regarded as a linear D-A-D structure, and the linearly positioned Cz pair in the D-A-D structure is identified as the origin of the deCT states. Notably, a D-A-D structure has been a common chemical template of TADF molecules, but the linear D-A-D structure proposed here is a new connection rule for the D and A moieties within a category of D-A-D structures. Furthermore, the linear D-A-D structure is extremely simple, and a combination of other kinds of D and A units may facilitate RISC by forming deCT states.

We next discuss a mechanism leading to high kRISC via deCT in terms of excited-state dynamics. Generally, RISC is intrinsically forbidden between 3CT and 1CT states because of a vanishing of the SOC matrix elements between their molecular orbitals and it is facilitated by SOC between 3LE and 1CT (25, 27). In addition, as Gibson et al. (27) demonstrated theoretically, a vibronic coupling between the 3CT and 3LE states plays a crucial role in the production of 1CT states via RISC. In this context, the energy gap to overcome for RISC is not ΔEST but the energy difference between 3LE and 1CT, as here defined to ΔEST(LE), and a mutual coupling among the T states in thermal equilibrium is the key for efficient RISC.

Figure 4D shows ΔEST(LE) and ΔEST of all the CzBN derivatives, which are taken from Fig. 2B. Here, the 3LE level observed only for 2CzBN is used as a common one for all the CzBN derivatives because the 3LE, which originates from a phenyl-Cz, is not significantly affected by adding acceptor substituents (see the phosphorescence spectrum of 2CzBN and TCzB in Fig. 2B). It is seen that, although the ΔEST(LE) values of the TADF-inactive molecules are similar to their ΔEST values (~0.2 eV), the ΔEST(LE) values of the TADF-active molecules are 0.12, 0.01, and −0.06 eV for p-3CzBN, 4CzBN, and 5CzBN, respectively, which are all smaller than their corresponding ΔEST values. This result is caused by the lowering of the S1 state for the TADF-active molecules, in line with the formation of a CT2 band in Fig. 4C. In addition, a dependence on ΔEST(LE) appears among the TADF-active molecules. Both 4CzBN and 5CzBN, which exhibit kRISC values that are one order of magnitude higher than the kRISC value of p-3CzBN, show smaller ΔEST(LE) values. These data suggest that, for the facilitation of RISC, a ΔEST of ~0.2 eV does not play a role, and instead, a ΔEST(LE) of less than 0.2 eV is needed; a large kRISC can be achieved by decreasing ΔEST(LE). To verify this idea, a comparison of an activation energy for the RISC among the TADF-active molecules may be needed, but a quite small TADF efficiency of p-3CzBN, ~4% at room temperature, made the comparison in the present stage difficult. The kRISC of 5CzBN is higher than that of 4CzBN despite the larger energy gap between de,3CT and 3LE for 5CzBN than for 4CzBN. We speculate that the reason for this is effective vibronic coupling among lo,3CT, 3LE, and de,3CT, as observed in the TAS of 5CzBN. An efficient vibronic coupling can occur between 3LE and de,3CT, but the coexistence of lo,3CT may assist the vibronic coupling in 5CzBN.

Finally, we propose a comprehensive design strategy for TADF molecules to obtain a high PLQY. Although 4CzBN and 5CzBN exhibited comparable kRISC, the PLQY of 4CzBN (62%) was lower than that of 5CzBN (85%) in solution (Table 1). This is ascribed to the high of 4CzBN, and p-3CzBN was found to have an even higher . We attribute the high to structural relaxation because the PLQY of 4CzBN increases to nearly 100% in a rigid matrix owing to the suppression of (1.7 × 104 s−1 in solution to 3.4 × 103 s−1 in rigid matrix). For the CzBN derivatives, the most probable relaxation is the twisting of the Cz moieties against the BN core (5). The of p-3CzBN was a few times higher than that of 5CzBN because there is no Cz at the 5-position, and twisting of the Cz moiety at the 6-position can easily occur (Fig. 1C). The absence of Cz at the 4-position for 4CzBN still produces the twisting of Cz moiety at 3- and 5-positions. As a result, the twisting of all the Cz moieties becomes most difficult for 5CzBN owing to the strong steric hindrance around each Cz moieties.

According to the Mulliken-Hush theory, the peak top of a CR band (VCR) is proportional to the electronic coupling (V) between the two redox sites (35); thus, the degree of structural relaxation can be rationalized by the VCR in the linearly positioned Cz pair. The VCR gradually shifts to lower energies in the order of p-3CzBN > 4CzBN > 5CzBN (fig. S6), indicating that p-3CzBN forms a more planar D-A-D structure in the T1 state because of V and, thus, VCR increases when the twisting angle of the D moieties becomes smaller (32). Therefore, we conclude that binding the linearly positioned Cz pair with surrounding bulky groups suppresses the structural relaxation, thereby contributing to a decreased while keeping a high kRISC. Consequently, the most rigid molecule, 5CzBN, shows the highest PLQY owing to the largest kRISC and lowest .

In summary, we clarified that the formation of a deCT is a driving force to promote a large kRISC even when ΔEST is not close to zero. We also pointed out the importance of the suppression of the structural relaxation in the T1 state to achieve a high PLQY. For CzBN derivatives, twisting of the linearly positioned Cz pair connected to the A-unit plane may occur depending on the free space around the Cz pair. This causes the structural relaxation to deactivate the T1 state. Accordingly, we propose a chemical structure to form deCT while suppressing the structural relaxation by introducing bulky moieties around linearly positioned D units in a D-A-D structure. The simple design strategy established here will be extremely beneficial for the design of new TADF molecules, and we believe that our work contributes to the progression of photochemistry and the development of high-performance OLEDs, as well as future molecular light-emitting devices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

4CzIPN, 2CzPN, m-3CzBN, 4CzBN, and 5CzBN were synthesized according to literature procedures (5, 20, 21). 2CzBN, o-3CzBN, and p-3CzBN were newly synthesized. The synthetic procedures and characterization are described in the Supplementary Materials. All the materials were purified by thermal sublimation. Solutions were prepared by dissolving the purified molecules in toluene (purity, 99.8%). The solution concentration was 10−3 to 10−5 M, depending on the samples and measurements.

Optical characterization of TADF molecules

The solutions were characterized by measuring the steady-state ultraviolet-visible (UV-VIS) absorption/PL spectra and TR-PL. TR-PL was measured using a C11367-01 spectrometer (Hamamatsu Photonics) or a Fluorocube fluorescence lifetime system (HORIBA). The PLQY of the solutions was measured by an absolute PLQY measurement system (C11347-01, Hamamatsu Photonics), with an excitation wavelength of 337 nm. Before the TAS and TR-PL measurements, the solutions were deoxygenated with dry nitrogen gas to eliminate the deactivation of triplets. The effect of deoxygenation was confirmed by comparing τprompt and τTADF values with those reported by Uoyama et al. (5).

OLED fabrication and characterization

Glass substrates with a prepatterned, 100-nm-thick, 100 ohm/square tin-doped indium oxide (ITO) coating were used as anodes. After precleaning of the substrates, effective device areas of 4 mm2 were defined on the patterned ITO substrates by a polyimide insulation layer using a conventional photolithography technique. Organic layers were formed by thermal evaporation. Doped emitting layers were deposited by coevaporation. Deposition was performed under vacuum at pressures <5 × 10−5 Pa. After device fabrication, devices were immediately encapsulated with glass lids using epoxy glue in a nitrogen-filled glove box [O2 < 0.1 parts per million (ppm) and H2O < 0.1 ppm]. OLEDs with the structure ITO/4,4′-cyclohexylidenebis[N,N-bis(4-methylphenyl)benzenamine] (TAPC) (35 nm)/mCP (10 nm)/dopant (15 wt %):PPT (30 nm)/PPT (40 nm)/LiF (0.8 nm)/Al (100 nm) were fabricated. The current density–voltage–luminance characteristics of the OLEDs were evaluated using a source measurement meter (B2912A, Agilent) and a calibrated spectroradiometer (CS-2000A, Konica Minolta Sensing Inc.). EL spectra were collected using a spectroradiometer (simultaneously with luminance). The ηEQE was calculated from the front luminance, current density, and EL spectrum. All measurements were performed under an ambient atmosphere at room temperature.

TAS measurements

Femtosecond-, nanosecond-, and microsecond-TAS measurements were conducted using different apparatuses developed in-house (28–30). For femtosecond-TAS, the output from a Ti:Al2O3 regenerative amplifier [Spectra-Physics, Hurricane, 800 nm; full width at half maximum (FWHM) pulse, 130 fs; repetition, 1 kHz] was used as the light source. The wavelength of the pump laser was 400 nm, which is a second harmonic of the fundamental light (800 nm) generated by a β-barium borate crystal, whereas the white-light continuum generated by focusing the fundamental beam (800 nm) onto a sapphire plate (2 mm thick) was used as the probe light. For nanosecond-TAS, we used the third harmonic of fundamental light (1064 nm) of a Nd3+:YAG laser (wavelength, 355 nm; FWHM pulse, <150 ps; repetition, 10 Hz) as the pump light and a xenon flash lamp as the probe light. The system of nanosecond-TAS was used for microsecond-TAS measurements, but the probe light was exchanged with a xenon steady-state lamp. Although the strong intensity of the flash lamp was suitable for measurements with a fast response time (~1 ns), the use of the steady lamp could cover Δt ~ 100 ms with a slow response time of 10 to 30 ns. The irradiated intensity of the pump laser was set to 0.21 and 0.27 mJ/cm2 for femtosecond-TAS measurements of 4CzPN and 2CzPN, respectively, and 0.7 to 1.4 mJ/cm2 for nanosecond- and microsecond-TAS of all the derivatives. After the TAS measurements, UV-VIS absorption spectra were measured to check the sample degradation by laser irradiation. We noted that the long-duration irradiation of the femtosecond-pulse laser gave rise to a decrease of a first CT band (CT2) in the UV-VIS absorption spectra, in particular for 4CzIPN (fig. S2). Therefore, we carefully conducted the TAS measurements by checking the data reproducibility. All measurements were carried out at 295 K. In Fig. 3A, ΔOD of the microsecond-TAS spectra at Δt = 4.6 and 30 μs was corrected with reference to the intensity of nanosecond-TAS at Δt = 27 ns; the ΔOD of the nanosecond-TAS was also corrected in advance using femtosecond-TAS at Δt = 2 ns. The linearity of ΔOD for each correcting process was guaranteed by considering the time resolution of microsecond- and nanosecond-TAS measurements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank W. J. Potscavage Jr. for assistance with the preparation of this manuscript and T. Yoshioka for assistance with this project. Funding: This work was supported, in part, by the “Development of Fundamental Evaluation Technology for Next-Generation Chemical Materials” program commissioned by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization, and the International Institute for Carbon Neutral Energy Research (WPI-I2CNER) sponsored by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). Author contributions: T.H. and H.M. performed TAS measurements and T.H., H.M., A.F., and H. Nakanotani analyzed the data. T.H. and H. Nakanotani determined photophysical properties and analyzed the data. K.N. and H. Nomura prepared CzPN and CzBN derivatives. H. Nakanotani fabricated OLEDs and analyzed the data. T.H. and H. Nakanotani coordinated the work and wrote the paper. K.T., T.T., M.Y., and C.A. conceived the project, and all authors critically commented on the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/5/e1603282/DC1

Synthesis and characterization of 2CzBN, o-3CzBN, and p-3CzBN

fig. S1. Time profiles of TAS of various triplet states of 4CzIPN and 2CzPN in toluene.

fig. S2. Steady-state absorption spectra.

fig. S3. Laser power dependence in TAS spectra.

fig. S4. TAS spectra of the CzBN derivatives.

fig. S5. TAS results of 3, 4, 6-p-3CzBN.

fig. S6. Energy position of CR band.

fig. S7. Emission spectra of CzPN derivatives.

fig. S8. Time profiles of TAS of triplet states of CzBN derivatives.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Baldo M. A., O’Brien D. F., Thompson M. E., Forrest S. R., Excitonic singlet-triplet ratio in a semiconducting organic thin film. Phys. Rev. B 60, 14422–14428 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 2.N. J. Turro, V. Ramamurthy, J. C. Scaiano, Principle of Molecular Photochemistry: An Introduction (University Science Books, 2009), chap. 3, pp. 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawamura Y., Goushi K., Brooks J., Brown J. J., Sasabe H., Adachi C., 100% phosphorescence quantum efficiency of Ir(III) complexes in organic semiconductor films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 071104 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adachi C., Third-generation organic electroluminescence materials. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 53, 060101 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uoyama H., Goushi K., Shizu K., Nomura H., Adachi C., Highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 492, 234–238 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dias F. B., Bourdakos K. N., Jankus V., Moss K. C., Kamtekar K. T., Bahlla V., Santos J., Bryce M. R., Monkman A. P., Triplet harvesting with 100% efficiency by way of thermally activated delayed fluorescence in charge transfer OLED emitters. Adv. Mater. 25, 3707–3714 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun J. W., Lee J.-H., Moon C. K., Kim K.-H., Shin H., Kim J.-J., A fluorescent organic light-emitting diode with 30% external quantum efficiency. Adv. Mater. 26, 5684–5688 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao Y., Yuan K., Chen T., Xu P., Li H., Chen R., Zheng C., Zhang L., Huang W., Thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials towards the breakthrough of organoelectronics. Adv. Mater. 26, 7931–7958 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S., Yao L., Peng Q., Li W., Pan Y., Xiao R., Gao Y., Gu C., Wang Z., Lu P., Li F., Su S., Yang B., Ma Y., Achieving a significantly increased efficiency in nondoped pure blue fluorescent OLED: A quasi-equivalent hybridized excited state. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 1755–1762 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee D. R., Kim M., Jeon S. K., Hwang S.-H., Lee C. W., Lee J. Y., Design strategy for 25% external quantum efficiency in green and blue thermally activated delayed fluorescent devices. Adv. Mater. 27, 5861–5867 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komatsu R., Sasabe H., Seino Y., Nakao K., Kido J., Light-blue thermally activated delayed fluorescent emitters realizing a high external quantum efficiency of 25% and unprecedented low drive voltages in OLEDs. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 2274–2278 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baleizão C., Berberan-Santos M. N., Thermally activated delayed fluorescence as a cycling process between excited singlet and triplet states: Application to the fullerenes. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 204510 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S. Y., Yasuda T., Nomura H., Adachi C., High-efficiency organic light-emitting diodes utilizing thermally activated delayed fluorescence from triazine-based donor–acceptor hybrid molecules. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 093306 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakagawa T., Ku S. Y., Wong K.-T., Adachi C., Electroluminescence based on thermally activated delayed fluorescence generated by a spirobifluorene donor–acceptor structure. Chem. Commun. 48, 9580–9582 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka H., Shizu K., Miyazaki H., Adachi C., Efficient green thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) from a phenoxazine–triphenyltriazine (PXZ–TRZ) derivative. Chem. Commun. 48, 11392–11394 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato K., Shizu K., Yoshimura K., Kawada A., Miyazaki H., Adachi C., Organic luminescent molecule with energetically equivalent singlet and triplet excited states for organic light-emitting diodes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 247401 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nasu K., Nakagawa T., Nomura H., Lin C., Chen C.-H., Tseng M.-R., Yasuda T., Adachi C., A highly luminescent spiro-anthracenone-based organic light-emitting diode exhibiting thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Chem. Commun. 49, 10385–10387 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masui K., Nakanotani H., Adachi C., Analysis of exciton annihilation in high-efficiency sky-blue organic light-emitting diodes with thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Org. Electron. 14, 2721–2726 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furukawa T., Nakanotani H., Inoue M., Adachi C., Dual enhancement of electroluminescence efficiency and operational stability by rapid upconversion of triplet excitons in OLEDs. Sci. Rep. 5, 8429 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang D. D., Cai M. H., Zhang Y. G., Zhang D. Q., Duan L., Sterically shielded blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters with improved efficiency and stability. Mater. Horiz. 3, 145–151 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang D., Cai M., Bin Z., Zhang Y., Zhang D., Duan L., Highly efficient blue thermally activated delayed fluorescent OLEDs with record-low driving voltages utilizing high triplet energy hosts with small singlet-triplet splittings. Chem. Sci. 7, 3355–3363 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondakov D. Y., Pawlik T. D., Hatwar T. K., Spindler J. P., Triplet annihilation exceeding spin statistical limit in highly efficient fluorescent organic light-emitting diodes. J. Appl. Phys. 106, 124510 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Data P., Pander P., Okazaki M., Takeda Y., Minakata S., Monkman A. P., Dibenzo[a,j]phenazine-cored donor–acceptor–donor compounds as green-to-red/NIR thermally activated delayed fluorescence organic light emitters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 5739–5744 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X.-K., Zhang S.-F., Fan J.-X., Ren A.-M., Nature of highly efficient thermally activated delayed fluorescence in organic light-emitting diode emitters: Nonadiabatic effect between excited states. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 9728–9733 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dias F. B., Santos J., Graves D. R., Data P., Nobuyasu R. S., Fox M. A., Batsanov A. S., Palmeira T., Berberan-Santos M. N., Bryce M. R., Monkman A. P., The role of local triplet excited states and D-A relative orientation in thermally activated delayed fluorescence: Photophysics and devices. Adv. Sci. 3, 1600080 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marian C. M., Mechanism of the triplet-to-singlet upconversion in the assistant dopant ACRXTN. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 3715–3721 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibson J., Monkman A. P., Penfold T. J., The importance of vibronic coupling for efficient reverse intersystem crossing in thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules. ChemPhysChem 17, 2956–2961 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshihara T., Murai M., Tamaki Y., Furube A., Katoh R., Trace analysis by transient absorption spectroscopy: Estimation of the solubility of C60 in polar solvents. Chem. Phys. Lett. 394, 161–164 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katoh R., Furube A., Fuke N., Fukui A., Koide N., Ultrafast relaxation as a possible limiting factor of electron injection efficiency in black dye sensitized nanocrystalline TiO2 films. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 22301–22306 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahanta S., Furube A., Matsuzaki H., Murakami T. N., Matsumoto H., Electron injection efficiency in Ru-dye sensitized TiO2 in the presence of room temperature ionic liquid solvents probed by femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy: Effect of varying anions. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 20213–20219 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto M., Tsujii Y., Tsuchida A., Near-infrared charge resonance band of intramolecular carbazole dimer radical cations studied by nanosecond laser photolysis. Chem. Phys. Lett. 154, 559–562 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaafarani B. R., Risko C., El-Assaad T. H., El-Ballouli A. O., Marder S. R., Barlow S., Mixed-valence cations of Di(carbazol-9-yl) biphenyl, tetrahydropyrene, and pyrene derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 3156–3166 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogiwara T., Wakikawa Y., Ikoma T., Mechanism of intersystem crossing of thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 3415–3418 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Q., Li J., Shizu K., Huang S., Hirata S., Miyazaki H., Adachi C., Design of efficient thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for pure blue organic light emitting diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 14706–14709 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heckmann A., Lambert C., Organic mixed-valence compounds: A playground for electrons and holes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 326–392 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/5/e1603282/DC1

Synthesis and characterization of 2CzBN, o-3CzBN, and p-3CzBN

fig. S1. Time profiles of TAS of various triplet states of 4CzIPN and 2CzPN in toluene.

fig. S2. Steady-state absorption spectra.

fig. S3. Laser power dependence in TAS spectra.

fig. S4. TAS spectra of the CzBN derivatives.

fig. S5. TAS results of 3, 4, 6-p-3CzBN.

fig. S6. Energy position of CR band.

fig. S7. Emission spectra of CzPN derivatives.

fig. S8. Time profiles of TAS of triplet states of CzBN derivatives.