Abstract

The fluorometric coupled enzyme assay to measure phosphatidic acid (PA) involves the solubilization of extracted lipids in Triton X-100, deacylation, and the oxidation of PA-derived glycerol-3-phosphate to produce hydrogen peroxide for conversion of Amplex Red to resorufin. The enzyme assay is sensitive, but plagued by high background fluorescence from the peroxide-containing detergent and incomplete heat inactivation of lipoprotein lipase. These problems affecting the assay reproducibility were obviated by the use of highly pure Triton X-100 and by sufficient heat inactivation of the lipase enzyme. The enzyme assay could accurately measure the PA content from the subcellular fractions of yeast cells.

Keywords: phosphatidic acid, coupled enzyme assay, fluorometric assay, phosphatidic acid phosphatase, yeast

The analysis of phosphatidic acid (PA) is essential to understand its role in the synthesis of membrane phospholipids and the neutral lipid triacylglycerol (1,2), and in lipid signaling (3,4). In our laboratory, we are interested in how the cellular level of PA is controlled by the action of the yeast Pah1 PA phosphatase, an enzyme that catalyzes the dephosphorylation of PA to yield diacylglycerol (5). The reaction product in yeast, as well as in higher eukaryotes, is required to synthesize triacylglycerol, and to synthesize phosphatidylcholine or phosphatidylethanolamine via the Kennedy pathway (1,2). In yeast, the substrate PA is a precursor for the de novo synthesis of all major membrane phospholipids, and governs the transcriptional regulation of several genes responsible for the synthesis of membrane phospholipids (3).

To determine the cellular levels of PA, we have used analytical methods such as thin-layer chromatography, high performance liquid chromatography, and mass spectrometry (5,6). While these methods can analyze PA and other lipids, they require relatively more effort or specific analytical instruments. For the measurement of PA, a coupled enzyme assay developed by Morita et al. (7) has generated much enthusiasm because it is highly sensitive, specific, and easy to perform. In the assay, lipids are extracted from the cell, solubilized in the nonionic detergent Triton X-100, and treated with lipoprotein lipase to remove fatty acyl moieties (7). Glycerol-3-phosphate, which is produced only from PA (or lysoPA), is oxidized by glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase to produce hydrogen peroxide, which is required to convert Amplex Red to resorufin, a fluorescent product (Ex544/Em590), by peroxidase (7). Several studies using the method have been published (8–15).

During the course of our work, we found that the method is plagued by high background fluorescence compromising the interpretation of the data. By examining each step of the enzyme assay, we identified that Triton X-100, which is used for lipid solubilization, is a major causative agent for background fluorescence. Many commercial preparations of Triton X-100 contain a high level (e.g., ~ 0.2%) of peroxides, and become the source of high background fluorescence. This caveat, which had not been discussed in the publication of the assay, could be addressed by using a highly pure preparation of Triton X-100 (e.g., Thermo Scientific, product no., 28314; Roche, product no., 1332481) that contains a very low level (e.g., ~ 0.002%) of peroxides.

Another source of high background fluorescence is the lipoprotein lipase used for deacylation of extracted lipids. Incubation of the lipase reaction mixture for 3 min at 96 °C was described to be sufficient to inactivate the enzyme, reducing background fluorescence by ~ 90% (7). However, we have found that the heat treatment is not sufficient to inactivate the lipase, and that incubation for at least 10 min in boiling water ensures the full inactivation of the enzyme.

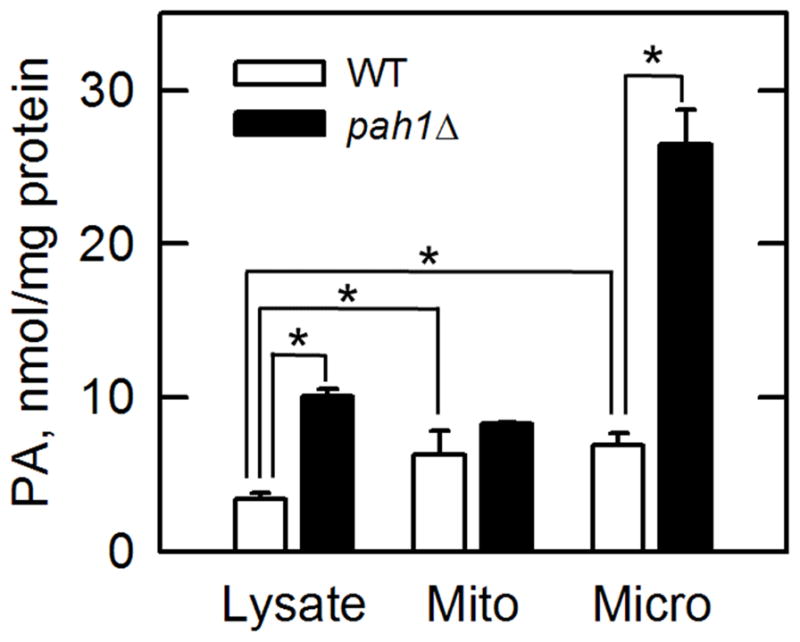

By controlling the two sources of non-specific fluorescence, we were able to reduce the background from > 800 to ~100 arbitrary units with our fluorescence spectrometer. We utilized the coupled enzyme assay to measure the PA content in pah1Δ mutant cells, which lack the Pah1 PA phosphatase enzyme. As described previously using thin-layer chromatography or high performance chromatography (5,6), the cellular content of PA (as reflected in the cell lysate) was higher in the mutant by 3-fold (Fig. 1). The cell lysate was fractionated into the mitochondrial and microsomal fractions (16), and the subcellular fractions were analyzed for PA levels using the coupled assay. In wild type cells, the concentration of PA was enriched in the mitochondrial and microsomal fractions by 2-fold (Fig. 1). Whereas the pah1Δ mutation did not have a significant effect on the PA content of the mitochondrial fraction, the mutation caused a 4-fold increase in the PA content of the microsomal fraction (Fig. 1), which is derived from endoplasmic reticulum membranes. This result supports the observation that Pah1 associates with the endoplasmic reticulum membrane to catalyze its PA phosphatase reaction (17,18).

Fig. 1. Measurement of PA levels in yeast subcellular fractions by the fluorometric coupled enzyme assay.

Wild type (WT) or pah1Δ mutant (5) cells were grown to the stationary phase in 250 ml YEPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% glucose) medium. The cells (~ 4 g wet weight) of each culture were harvested by centrifugation, treated with lyticase, and the resulting spheroplasts were lysed using a Dounce homogenizer. 90% of the cell lysate was fractionated by differential centrifugation (16), and the lipids were extracted (19) from the lysate and subcellular fractions. The lipid extracts were solubilized in 0.5 ml of 1% Triton X-100 (Surfact-Amps, < 1.0 μeq/ml peroxides, Thermo Scientific), and 20 μl of the samples were treated with 2,400 units (μmol/min) Pseudomonas sp. lipoprotein lipase (Wako). The lipase was inactivated by boiling for 10 min and the denatured protein was removed by centrifugation. Glycerol-3-phosphate derived from PA was oxidized by 0.5 unit (μmol/min) Aerococcus viridans glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase (Sigma-Aldrich) to produce hydrogen peroxide, which was then used for the conversion of Amplex Red (10-Acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine, Thermo Scientific) to resorufin by 0.5 unit (μmol/min) horseradish peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich) (7). The last two steps in the coupled enzyme reaction were carried out for 30 min at room temperature in a black 96-well plate, and the resulting fluorescence was immediately measured by Agilent Technologies Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrometer. The Amplex Red stop solution (7), which is ineffective in stopping the peroxidase reaction under the conditions of the assay, was not used in this work. A standard curve with dioleoyl PA (Avanti Polar Lipids) (200 to 1,000 pmol, linear range) was used to quantify the phospholipid in the extracted lipids. The data are averages ± S.D. (error bars) from triplicate determinations. *, p < 0.01.

In summary, the fluorometric coupled enzyme assay for PA measurement (7) is an excellent method, and can be readily reproducible by utilizing a highly purified preparation of the Triton X-100 detergent and extending the time for the heat inactivation of the lipoprotein lipase. Here we showed the method to be useful for measuring PA from yeast, and as shown previously (7), the method is useful for measuring the phospholipid from mammalian cells.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM028140.

Abbreviations

- PA

phosphatidic acid

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the contents of this article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carman GM, Han GS. Regulation of phospholipid synthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ann Rev Biochem. 2011;80:859–883. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060409-092229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henry SA, Kohlwein S, Carman GM. Metabolism and regulation of glycerolipids in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;190:317–349. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.130286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carman GM, Henry SA. Phosphatidic acid plays a central role in the transcriptional regulation of glycerophospholipid synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37293–37297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700038200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster DA. Regulation of mTOR by phosphatidic acid? Cancer Res. 2007;67:1–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han GS, Wu WI, Carman GM. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae lipin homolog is a Mg2+-dependent phosphatidate phosphatase enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9210–9218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600425200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fakas S, Qiu Y, Dixon JL, Han GS, Ruggles KV, Garbarino J, Sturley SL, Carman GM. Phosphatidate phosphatase activity plays a key role in protection against fatty acid-induced toxicity in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:29074–29085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morita SY, Ueda K, Kitagawa S. Enzymatic measurement of phosphatidic acid in cultured cells. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1945–1952. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D900014-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sembongi H, Miranda M, Han G-S, Fakas S, Grimsey N, Vendrell J, Carman GM, Siniossoglou S. Distinct roles of the phosphatidate phosphatases lipin 1 and 2 during adipogenesis and lipid droplet biogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. J Biol Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.488445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang P, Takeuchi K, Csaki LS, Reue K. Lipin-1 Phosphatidic Phosphatase Activity Modulates Phosphatidate Levels to Promote Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor gamma (PPARgamma) Gene Expression during Adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:3485–3494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.296681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlam D, Bohdanowicz M, Chatgilialoglu A, Steinberg BE, Ueyama T, Du G, Grinstein S, Fairn GD. Diacylglycerol kinases terminate diacylglycerol signaling during the respiratory burst leading to heterogeneous phagosomal NADPH oxidase activation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:23090–23104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.457606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giridharan SS, Cai B, Vitale N, Naslavsky N, Caplan S. Cooperation of MICAL-L1, syndapin2, and phosphatidic acid in tubular recycling endosome biogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:1776–15. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-01-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohdanowicz M, Schlam D, Hermansson M, Rizzuti D, Fairn GD, Ueyama T, Somerharju P, Du G, Grinstein S. Phosphatidic acid is required for the constitutive ruffling and macropinocytosis of phagocytes. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:1700–1707. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-11-0789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shirai Y, Kouzuki T, Kakefuda K, Moriguchi S, Oyagi A, Horie K, Morita SY, Shimazawa M, Fukunaga K, Takeda J, Saito N, Hara H. Essential role of neuron-enriched diacylglycerol kinase (DGK), DGKβ in neurite spine formation, contributing to cognitive function. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antonescu CN, Danuser G, Schmid SL. Phosphatidic acid plays a regulatory role in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2944–2952. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-05-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiu Y, Hassaninasab A, Han GS, Carman GM. Phosphorylation of Dgk1 diacylglycerol kinase by casein kinase II regulates phosphatidic acid production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:26455–26467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.763839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meisinger C, Pfanner N, Truscott KN. Isolation of yeast mitochondria. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;313:33–39. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-958-3:033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karanasios E, Han GS, Xu Z, Carman GM, Siniossoglou S. A phosphorylation-regulated amphipathic helix controls the membrane translocation and function of the yeast phosphatidate phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17539–17544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007974107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karanasios E, Barbosa AD, Sembongi H, Mari M, Han GS, Reggiori F, Carman GM, Siniossoglou S. Regulation of lipid droplet and membrane biogenesis by the acidic tail of the phosphatidate phosphatase Pah1p. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:2124–2133. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-01-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]