Abstract

Staged marginal evaluation of melanoma in situ (MIS) is performed in order to avoid reconstruction on positive margins. Contoured marginal excision (CME) is an excision of a 2mm wide strip of normal-appearing skin taken 5mm from the visible tumor periphery. If positive, a new CME is excised; the tumor is resected once negative margins are confirmed. The purpose of this study is to report our experience using this technique for the treatment of head/neck MIS. Clinicopathological data were abstracted for all patients who underwent staged CME followed by central tumor resection for head/neck MIS; patients with invasive melanoma were excluded. Statistical analyses included χ2 and t-test. Overall, 127 patients with MIS were identified. 56% were male; the average age was 68 years. The median number of CME procedures per patient was 1 (range 1 to 4). 23% of patients required more than one CME procedure to achieve negative margins. Local recurrence occurred in 3/127 patients after a median follow-up of 5 months. Patients requiring multiple CME procedures were more likely to experience local recurrence (P<0.001). In conclusion, this technique is an effective method to avoid reconstruction on positive MIS margins with high local disease control rates.

Keywords: melanoma in situ, contoured marginal excision, staged excision, picture frame technique

Melanoma in situ (MIS) on sun-damaged skin (lentigo maligna) is associated with chronic ultraviolet light exposure and can pose a treatment dilemma due to microscopically positive margins after excision, since the tumor frequently extends beyond the clinically visible edges. A 5 mm margin is conventionally recommended for treatment, but is associated with recurrence rates up to 20%.1,2 Historically, up to 50% of patients may have histologically positive margins after 5 mm margin excisions.1,2 Several techniques have been utilized to assure negative margins before reconstruction.1–4

Staged contoured marginal excision (CME) followed by central tumor resection and reconstruction is a simple approach to confirm negative margins pathologically prior to definitive tumor resection and reconstruction.1,4,5 This is a variation of the picture frame approach, but we utilize aesthetic incisions (e.g., nasolabial fold), and consider aesthetic units (e.g., nasal alar base) to maximize the final aesthetic outcomes.6,7 The CME procedure involves removing curvilinear strips of normal-appearing skin approximately 5 mm away from gross visible tumor and is performed as described below.

This study investigated the utility of CME followed by central tumor resection in the treatment of head and neck MIS. We specifically excluded patients with a pre-existing diagnosis of invasive melanoma elsewhere, or with invasive melanoma present along with melanoma in situ (lentigo maligna melanoma), in order to accurately characterize the recurrence potential for melanoma in situ after CME. Other groups have demonstrated that the invasive component will dominate the overall survival in those patients with both invasive and non-invasive malignancies.8,9

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Subjects

Clinicopathological, surgical, and recurrence data were abstracted for all patients who underwent staged CME followed by central tumor resection for head or neck MIS from 2006–15. Patients with an invasive melanoma component or with a preexisting diagnosis of invasive melanoma at the time of MIS diagnosis were excluded. All specimens were reviewed by a Moffitt Cancer Center dermatopathologist prior to treatment. Postoperatively, patients are seen about 2 weeks after resection and 3 months after resection, then followed at least every 6 months by their referring dermatologist or a dermatologist at our institution. The institutional review board approved this retrospective data review.

Surgical/pathological technique

All patients with MIS on the head and neck with no medical contraindications to surgery were considered for treatment by staged CME and subsequent central tumor excision and reconstruction (Figure 1). The CME procedure involves removing 2 to 3 mm wide curvilinear strips of normal-appearing skin approximately 5 mm away from gross visible pigmentation/tumor and from any areas of depigmentation beyond gross tumor noted on Wood’s lamp interrogation (Figures 1A and 1B). The strips are fashioned to conform to the aesthetic lines at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2). Each strip (4–5 per CME procedure) is oriented for the pathologist (Figure 1C). The narrow CME defects (~2mm) are temporarily closed primarily (i.e., running 3-0 nylon). The thickness of the CME (~2mm) is the narrowest width of skin that can be reliably be excised and oriented for fixation and pathologic analysis. Often, the CME procedure is performed in an office setting with local anesthesia. Each margin specimen is embedded in toto in tangential fashion. The outer edge is cut first and evaluated by H&E staining and immunohistochemistry using S-100, Melan-A, MITF, and/or Sox10 if indicated to evaluate melanocyte density, confluence, and/or pagetoid spread. If any strip in the first CME procedure demonstrates MIS on final pathological evaluation, then an additional CME is performed at that margin (Figure 1D, on the inferior and posterior margins). This is repeated until all the margins are negative on final pathologic evaluation (Figure 3). Turnaround time for each stage is approximately 3–5 working days. No further margins are excised if the positive margin is at the ciliary line of the eyelid, the intranasal skin of the nose alar rim, or if the patient refuses further surgery. The final CME margins serve as the boundary for central tumor resection with immediate reconstruction. This procedure usually requires general anesthesia but is almost always performed as an outpatient operation. Reconstruction is performed at the discretion of the surgeon with skin flaps, skin grafts, wound matrix, or primary closure.

Figure 1.

Contoured marginal excision (CME) for melanoma in situ on the left face with poorly demarcated margins (A); after marginal excision (B); specimens oriented for the pathologist (C); and repeat CME performed for positive inferior and posterior margins on the initial CME (D).

Figure 2.

The contoured marginal excision specimens are excised considering the configuration of tumor, aesthetic lines, aesthetic units, and relaxed skin tension lines. (A). The strips of skin are sharply incised (B) and excised (C).

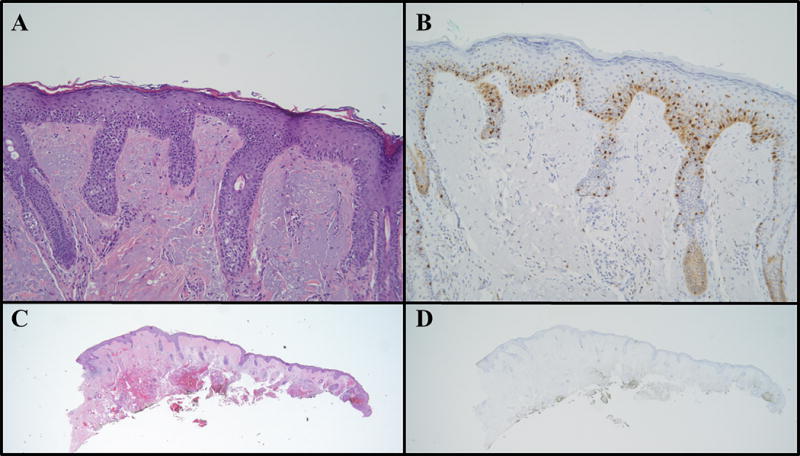

Figure 3.

Melanoma in situ is seen in the contoured marginal excision specimen from the eyelid of a 76-year-old female, (A) with hematoxylin & eosin stain (100×), and (B) with MITF immunohistochemistry (100×). Subsequent specimens from a second contoured marginal excision procedure were negative with both hematoxylin & eosin stains (C, 12.5×) and MITF immunohistochemistry (D, 12.5×).

Local recurrences were defined as MIS or invasive melanoma within 2 cm adjacent to the reconstruction/scar.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance, α, was set at P = 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with χ2, Student’s t-test, and logistic regression. Recurrence-free survival hazards were determined with Cox proportional hazard models; the number of CMEs was investigated as a continuous as well as a categorical variable (1–2 vs 3–4 CMEs).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

130 patients were identified who underwent staged CME for a preoperative diagnosis of MIS of the head or neck and no history of invasive melanoma. Of these, 3 patients were found to have invasive melanoma in the central tumor resection and were excluded from analysis of local and regional recurrence, leaving 127 patients with MIS. Table 1 lists the patient characteristics for all patients in the study (n = 130) and for the 127 patients without incidentally found invasive melanoma, broken down further by the number of CME procedures that the patients underwent before central tumor resection.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | 1–2 CMEs N = 117 |

3–4 CMEs N = 10 |

Univariate P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD years | 68 ± 13 | 71 ± 15 | 0.53 | |

|

| ||||

| Gender, male n (%) | 68 (58%) | 3 (30%) | 0.09 | |

|

| ||||

| Site | Face, n (%) |

96 (82%) | 10 (100%) | 0.54 |

| Ear, n (%) | 5 (4%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Scalp, n (%) | 12 (10%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Neck, n (%) | 4(3%) | 0 (0%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Clinical tumor diameter (maximum), mean ± SD cm | 2.9 ± 1.9 | 3.8 ± 2.5 | 0.18 | |

|

| ||||

| Positive margin, n (%) | 4 (3.4%) | 2 (20%) | 0.02 | |

|

| ||||

| Local recurrence, n (%) | 1 (0.9%) | 2 (20%) | 0.0001 | |

SD: standard deviation, CME: contoured marginal excision

Totals do not always equal 100% due to rounding.

Of the 127 patients, 56% were male, 83% of the lesions were on the face, and the average age was 68 years (range 30 to 92 years). Ninety-two percent of patients had the lentigo maligna subtype of MIS; the remainder were superficial spreading MIS. The median follow up was 5.4 months, with a range from 1 to 101 months and a mean follow up of 9.9 months.

Contoured marginal excisions

The median number of CME procedures was 1 (range 1 to 4). Final margins were negative in 95% of patients, but 29 patients (22.8%) required two or more CME procedures to achieve negative margins.

Of the 127 patients, negative margins were not achieved in 6 patients (4.7% positive margin rate). Three of these 6 patients had positive margins on the edge of the eyelid and 1 patient had a positive margin on the inner aspect of nasal ala with no further skin to excise. Two of the 6 patients had positive margins on the cheek but refused to undergo further CMEs. Both of these patients were octogenarians and decided against further CMEs after discussion with their primary surgeon. There were no recurrences in this group of 6 patients with positive margins, at a median follow up of 7.8 months (range 2 to 37 months, mean 11.3 months).

Reconstruction

After central tumor resection, the median final tissue defect size was 10 cm2 with a range from 1.5 to 210 cm2. Reconstruction was completed with local flaps (36%), skin grafts (59%), wound matrix (2%), or primary closure (3%). Twelve of the 29 patients (41%) with MIS in the initial CME were eventually reconstructed with local flaps while the rest were reconstructed with skin grafts after further CMEs were excised. Primary closure was occasionally utilized when there was sufficient laxity in the skin (e.g., on the neck). We utilized wound matrix only when other options were inadequate, predominantly due to patient-related issues. Full-thickness skin grafts were often utilized for small to moderate sized defects not amenable to primary closure, and were harvested from easily accessible sites.

Recurrence

At last follow up, three of the 127 MIS patients (2.4%) developed locally recurrent MIS. These three patients underwent 1, 3, and 4 CME procedures to achieve negative margins after their original diagnosis, respectively. There was no difference in the average area of initial visible MIS between those patients who recurred and those who did not recur (P=0.8). The follow up for those three patients who recurred was 3, 26, and 26 months, respectively. All three patients who recurred were re-resected with negative margins. One of those patients was found to have a dermal nodule of invasive melanoma adjacent to the site of MIS recurrence. No patients developed regional or distant metastatic disease. Increased risk for recurrence was associated with the number of individual CME procedures (Cox proportional hazard ratio = 3.0 for each additional CME, P = 0.039) as well as comparing 1–2 vs 3–4 CMEs (P < 0.001, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Recurrence rate for melanoma in situ (MIS) is related to the number of contoured marginal excision procedures (CMEs) required (P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Appropriately managing the subclinical extent of MIS- pathologically positive but visibly negative tissue- is the greatest challenge in managing this disease. Confirming negative margins prior to definitive central tumor resection and reconstruction is critically important in order to avoid reconstruction on tumor-positive margins, avoid subsequent operations, and to minimize the chance of local recurrence. Additionally, pathologic examination of specimens re-excised after positive margins can be challenging due to changes secondary to the prior procedure. The staged CME procedure enables pathologic analysis of the entire peripheral surgical margin. In our series, 23% of patients with MIS of the head and neck had disease beyond the recommended 5 mm resection margins based on a positive first CME at that distance. It is difficult to identify these patients preoperatively by clinical examination, especially with lentigo maligna. Other groups have demonstrated local recurrence rates for MIS as high as 20%1,2 whereas it was 2.4% in this series, albeit with short follow-up. This highlights the potential advantage of staged CME and central resection. It is interesting that the reported local recurrence rate in the literature is similar to our CME positivity rate at the first procedure, suggesting biologic plausibility.

The ultimate goal of resecting MIS is to prevent the progression to invasive melanoma.10 In this series of 127 patients with MIS, the recurrence rate of MIS was 2.4% with only 1 of the 3 patients who recurred developing an invasive melanoma. Assuming that the underlying goal in treating MIS in patients is the prevention of invasive melanoma, then we report a failure to cure rate of 0.8% (1/127). Of note, three patients with a preoperative diagnosis of MIS were found to have invasive melanoma in the central tumor resection specimen and were excluded from this analysis. One of those three patients had an invasive melanoma 1.5 mm in depth and underwent further resection and a delayed sentinel lymph node biopsy, which was negative. The other two patients had invasive melanomas less than 0.3 mm in depth and underwent wide resection. None of these three patients recurred with a median follow up of 9 months (range 5 months to 12 months). A recent study by Gardner et al. demonstrated that 4% of patients with head and neck MIS were found to have invasive melanoma upon final resection.11 In addition, in that study, 4 out of 624 patients (0.6%) were found to have an invasive melanoma more than 5 mm away from the primary MIS lesion.

Treatment options for MIS also include Mohs micrographic surgery and topical therapy. Micrographic surgical excision with delayed reconstruction after immunohistochemistry evaluation is an option and has recurrence rates of approximately 5%.12 An advantage of micrographic surgery is that patients can potentially have pathologic evaluation and reconstruction on the same day. However, reconstruction is often delayed one or more days even after micrographic surgery, and these patients will have an open wound until the reconstruction is completed. A major disadvantage of micrographic surgery is the challenge associated with interpreting MIS on frozen section evaluation, even with the use of immunohistochemical stains, compared to permanent sections obtained for evaluation with the CME procedure. Importantly, excising the CME starting at a 5mm distance from the MIS assures that no patients are receiving sub-standard of care margins (i.e., less than 5 mm).

Another treatment option involves topical therapy, such as imiquimod, which has been reported to be an effective therapy in selected patients with limited disease or medical contraindications to surgery. However, this approach suffers from the inability to examine pathologic tissue for occult invasive melanoma.13–14

Optimal reconstruction near critical aesthetic and functional structures is a challenge and should be accomplished with minimal risk of recurrence, maintenance of cosmesis, and maximal preservation of these structures (Figure 2). Maintaining functional and cosmetic status is especially paramount considering that MIS is not a life-threatening disease. Utilizing staged CME does require at least two procedures but is associated with an acceptably low recurrence rate and a very low rate of invasive recurrence (1 out of 127 patients in this series). Importantly, the initial staged CME procedure can be performed with local anesthesia in an office-type setting in order to minimize anesthetic risks.

The relatively short follow up and long time period of this study are both limitations to generalizing these results. Our practice is to evaluate patients with MIS approximately 3 months after resection and reconstruction in order to confirm that there is no evidence of disease and all wounds healed well. At that point, patients are typically referred back to their local dermatologist for continued skin surveillance (at least twice yearly). It is common practice for patients to be referred back to our institution if further MIS or melanoma lesions are diagnosed, but this clearly remains a limitation of this study.

There are two noteworthy limitations to the staged CME technique itself. First, there are anesthetic risks as patients are undergoing multiple operations. Performing the first CME procedure under local anesthesia with or without sedation, however, minimizes this risk. Second, if an invasive melanoma over 0.75 mm is identified after central tumor resection, then a subsequent sentinel lymph node biopsy may not be reliable. The true sentinel lymph node may not be identified because lymphatic channels have been disrupted during the CME procedure but a large series by Gannon et al demonstrated overall success in staged sentinel lymph node biopsy after wide excision of invasive melanoma in highly selected patients.15 Surveillance of the lymph node basin with serial ultrasound examination is an alternative or adjunct to sentinel node biopsy in these patients.16

In conclusion, staged CME followed by central tumor resection is an effective method to treat MIS on the head and neck. Twenty-three percent of these patients would have had positive margins if treated by standard excision with 5 mm margins, as proposed by most guidelines. Lesions with larger subclinical extent (i.e., requiring more than two CMEs) had a significantly higher rate of local recurrence and may represent tumors for which more intensive surveillance or adjunctive means to reduce local recurrence should be investigated.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported in part by the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292), and the Department of Surgery at the University of South Florida. A portion of this manuscript was presented at the 2016 SSO Annual Cancer Symposium.

Footnotes

Conflicts/disclosures: The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this research.

References

- 1.Moller MG, Pappas-Politis E, Zager JS, et al. Surgical Management of Melanoma-in-Situ Using a Staged Marginal and Central Excision Technique. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2009;16:1526–1536. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunishige JH, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Surgical Margins for Melanoma in Situ. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2012;66:438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins HW, II, Lee KC, Galan A, Leffell DJ. Melanoma in Situ Part Ii. Histopathology, Treatment, and Clinical Management. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2015;73:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messina J, Moller MG, Sondak VK, et al. The Contoured Staged Marginal and Central Surgical Excision Technique with En Face Histopathological Analysis: Useful Additions in the Armamentarium for Treating and Diagnosing Melanoma in Situ. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2009;16:2654–2655. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0600-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia Bracamonte B, Palencia-Perez SI, Petiti G, Vanaclocha-Sebastian F. The Perimeter Technique in the Surgical Treatment of Lentigo Maligna and Lentigo Maligna Melanoma. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2012;103:748–750. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cotter MA, McKenna JK, Bowen GM. Treatment of Lentigo Maligna with Imiquimod before Staged Excision. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34:147–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark GS, Pappas-Politis EC, Cherpelis BS, et al. Surgical Management of Melanoma in Situ on Chronically Sun-Damaged Skin. Cancer Control. 2008;15:216–224. doi: 10.1177/107327480801500304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Youlden DR, Khosrotehrani K, Green AC, et al. Diagnosis of an Additional in Situ Melanoma Does Not Influence Survival for Patients with a Single Invasive Melanoma: A Registry-Based Follow-up Study. The Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 2016;57:57–60. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackwood MA, Holmes R, Synnestvedt M, et al. Multiple Primary Melanoma Revisited. Cancer. 2002;94:2248–2255. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tannous ZS, Lerner LH, Duncan LM, et al. Progression to Invasive Melanoma from Malignant Melanoma in Situ, Lentigo Maligna Type. Human Pathology. 2000;31:705–708. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.7640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner KH, Hill DE, Wright AC, et al. Upstaging from Melanoma in Situ to Invasive Melanoma on the Head and Neck after Complete Surgical Resection. Dermatologic Surgery. 2015;41:1122–1125. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenna JK, Florell SR, Goldman GD, Bowen GM. Lentigo Maligna/Lentigo Maligna Melanoma: Current State of Diagnosis and Treatment. Dermatologic Surgery. 2006;32:493–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandit AS, Geiger EJ, Ariyan S, et al. Using Topical Imiquimod for the Management of Positive in Situ Margins after Melanoma Resection. Cancer Medicine. 2015;4:507–512. doi: 10.1002/cam4.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spenny ML, Walford J, Werchniak AE, et al. Lentigo Maligna (Melanoma in Situ) Treated with Imiquimod Cream 5%: 12 Case Reports. Cutis. 2007;79:149–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gannon CJ, Rousseau DL, Jr, Ross MI, et al. Accuracy of Lymphatic Mapping and Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy after Previous Wide Local Excision in Patients with Primary Melanoma. Cancer. 2006;107:2647–2652. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voit CA, van Akkooi AC, Eggermont AM, et al. Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology of Palpable and Nonpalpable Lymph Nodes to Detect Metastatic Melanoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2011;103:1771–1777. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]