Highlights

-

•

Only case in literature without history of endometriosis, on Hormone replacement therapy.

-

•

Only the second case with isolated omental lesion.

-

•

Extrauterine Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma (EESS) is an extremely rare mesenchymal tumour.

-

•

This condition can simulate chronic or acute abdominal pathologies.

-

•

The tumour can occur without preceding endometriosis, and in upper abdominal location.

-

•

Biopsy showing typical immunohistochemistry markers is the best way to achieve diagnosis.

-

•

Hormone replacement therapy may be an independent risk factor for EESS occurrence.

Keywords: Endometrial stromal sarcoma, Extrauterine, Omentum, Hormone replacement therapy

Abstract

Introduction

Extrauterine Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma (EESS) is an extremely rare mesenchymal tumour that simulates other pathologies, and therefore poses a diagnostic challenge. This report outlines a case of EESS arising from the greater omentum mimicking a colonic tumour, with review of literature.

Presentation of case

A 47-year-old woman, with history of hysterectomy for menorrhagia and hormone replacement therapy (HRT), presented with right sided abdominal pain and localized peritonism. On exploratory laparoscopy an omental tumour, suspected to arise from the transverse colon was identified and biopsied. The histological features suggested an EESS. Colonoscopy ruled out colonic lesion. A laparoscopic tumour resection and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) was performed. Immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis. No additional lesions or associated endometriosis were found. Resection was followed by adjuvant medroxyprogesterone-acetate therapy.

Discussion

We reviewed 20 cases of EESS originating from extragenital abdominopelvic organs reported since 1990. Acute presentation is rare, as well as upper abdominal occurrence. Isolated omental involvement was previously reported in only one case. Endometriosis is a risk factor for development of EESS and history and/or histological evidence for endometriosis is usually present. HRT is another acknowledged risk factor, mostly on the background of endometriosis. To our knowledge, this is the only report of EESS occurring in a woman on HRT treatment without background of endometriosis.

Conclusion

EESS can occur without endometriosis and HRT may be an aetiological factor. The condition can mimic a chronic or acute abdominal pathology and laparoscopic core biopsy is the best way to achieve a diagnosis and formulate management.

1. Introduction

Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) is a rare mesenchymal tumour of the uterus. It may also arise as a primary extrauterine endometrial sarcoma (EESS), mainly on the background of endometriosis, with predominant gonadal involvement as a result. Very rarely does EESS arise primarily in the gastrointestinal or extra-gastrointestinal tract organs outside the pelvis, or evolve without preceding endometriosis [1]. In these cases, the non-specific presentation and the unexpected location pose a diagnostic challenge [2], [3], and often another abdominal pathology is first suspected. A case of primary EESS arising from omentum mimicking a colonic primary is presented, with review of the literature. This report is line with the SCARE criteria [4].

2. Presentation of case

A 47-year-old female, presented to the Emergency Department with right sided and central abdominal pain. Her medical history included hysterectomy 10 years earlier for menorrhagia, and HRT with oestradiol patch. She reported vague, generalized abdominal pain, mainly central, which later migrated to the right lower abdomen. On examination she was tender along the right and upper central abdomen with localized peritonism. WBC and CRP were elevated (12.1 × 109/L, 16 mg/L respectively). Sonography demonstrated a hypoechoic, ovoid, irregular lesion with blind end, and sonographic probe induced tenderness above it. Given the acute presentation, and the high suspicion for an inflammatory lesion, the patient was taken for an exploratory laparoscopy. At surgery, a firm irregular omental mass was found, located above the proximal transverse colon, near the hepatic flexure. The lesion seemed to extend from the colon. The Appendix was normal. Prior hysterectomy was noted, right ovary and tube were normal, however optimal view of the left adnexa was impossible due to pelvic small bowel adhesions. No other pathology was found. A partially necrotic omental nodule adjacent to the larger eccentric mass was biopsied. The specimen consisted of an 18 × 15 × 12 mm nodule, with extensive haemorrhagic necrosis. The residual tissue was comprised of monomorphic ovoid to spindle-shaped cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. The morphology suggested a mesenchymal-type lesion, but immunohistochemistry with a panel of antibodies, raised the possibility of endometrial stromal sarcoma.

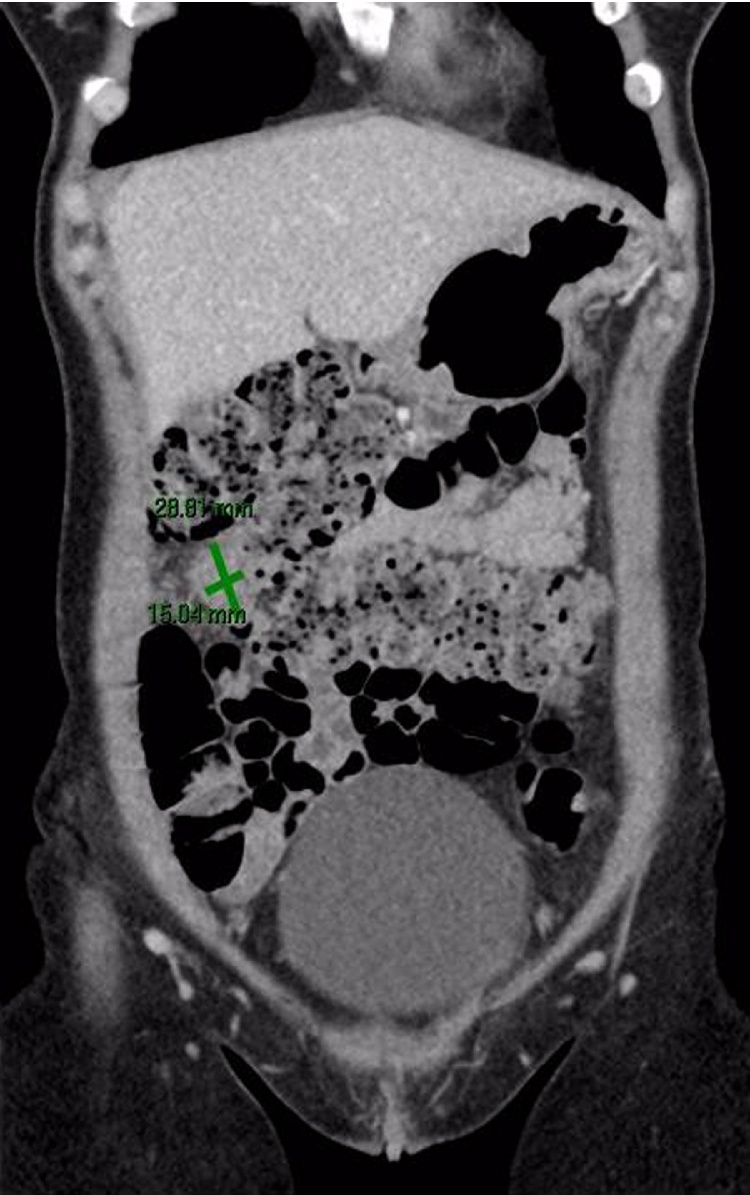

Given the rarity of this diagnosis without previous ESS and endometriosis, the past hysterectomy slides were reviewed and confirmed as benign without any evidence of ESS. The current and previous slides were sent for a second external review which supported the diagnosis of primary EESS. A systemic workup was then undertaken. Chest, abdomen and pelvis computed tomography demonstrated a 28 × 15 mm ovoid mass arising from the transverse colon, without evidence for distant metastasis or nodal disease (Fig. 1). Tumour markers (CA19.9, CA-125, CEA, AFP) were negative. Colonoscopy excluded primary or secondary colon involvement. The patient was discussed by the Surgical and Gynae-Oncology multidisciplinary teams. The decision was to proceed with laparoscopic excision of the tumour together with BSO by joint surgical and gynaecology teams. A two centimetre omental lesion was found next to the hepatic flexure and resected. Pelvic small bowel loops were adhesiolysed and normal looking ovaries and tubes were resected. No peritoneal spread or other metastatic lesions were identified. The post-operative recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged on day one post surgery.

Fig. 1.

(Greyscale and colour). Contrast enhancement coronal computed tomography showing showing ovoid mass in proximity to transverse colon.

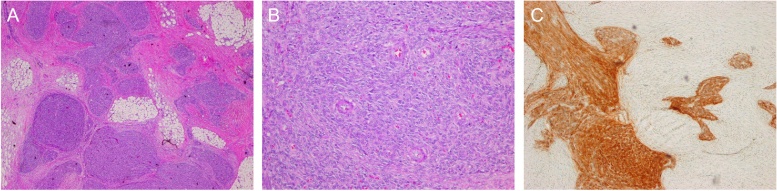

The omental lesion contained a firm nodule measuring 21 mm in maximal dimension. The mass was characterized by multiple foci of ovoid to spindle–shaped cells forming irregular tongues dissecting through markedly fibroblastic stroma (Fig. 2a). The cells were uniform with rare mitotic figures. Small capillary-sized blood vessels were found within the proliferative cells (Fig. 2b). The tumour cells stained strongly for CD10 (Fig. 2c), oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, vimentin, WT-1 and Bcl-2. There was no reaction for c-Kit, CD34, desmin, or smooth muscle actin. Both ovaries and fallopian tubes were normal. The morphology and immunoprofile were compatible with the diagnosis of primary extrauterine low grade ESS originating from the omentum. HRT was ceased and the patient was put on adjuvant hormonal therapy with medroxyprogesterone acetate and was scheduled for regular follow-up.

Fig. 2.

(Colour image). (A) Islands of spindle-shaped tumour cells infiltrating into omental fat. (B) Uniform population of spindle small with embedded prominent capillary-sized vessels/or arterioles. (C) Strong immunoreaction of cells for CD10.

3. Discussion

Extrauterine endometrial sarcoma involving an extra-genital site is an extremely rare condition. It is even more rare to find it in the upper abdomen and without any clinical evidence of endometriosis. Even fewer cases of upper abdominal ESS without clinical evidence of endometriosis have been described in the literature. All 20 reported cases (including the present case) reported since 1990 were reviewed. These are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical features of extaruterine extraovarian abdominopelvic ESS.

| Authors | Age (yr) | Past History/HRT | Presenting symptoms | Abdominal Site | Gross Findings | Dissemination | Associated Endometriosis (specimen) | Treatment | Follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Son et al. [5] | 52 | None | Constipation, abdominal pain and hematochezia (1 mo) |

Sigmoid colon | 3.5 × 2.8 cm polypoid mass involving whole layers of colonic wall to pericolic fat | Local (pelvic, peritoneum, ovaries) | No | Laparoscopic LAR TAH, BSO (2mo later) |

NED, 4 mo |

| Wang et al. [6] | 40 | TAH (leiomyoma) Rt. Ovarian cystectomy |

Change in bowel habits and hematochezia (1 yr) |

Rectosigmoid, mesentery, intestinal wall | Multiple 1–3 cm nodular masses involving intestinal wall and mesentery | Distant (multiple mesentery and abdominal metastasis) | Yes | Intraoperative chemotherapy, palliative transverse loop colostomy | DOD, 18 mo |

| Ghosal et al. [15] | 42 | None | Palpable mass (1 mo) | Transverse and sigmoid colon mesentery, peritoneum | Multiple 0.7–2.8 cm nodular masses involving mesentery and peritoneum | Distant (multiple abdominal metastasis, para-aortic LNs) | Yes | TAH, BSO, resection of abdominal nodules, and pelvic and para-aortic nodes | NA |

| Ayuso et al. [7] | 80 | TAH, BSO (endometriosis/abnormal bleeding) HRT |

Hematochesia Chronic discharge |

Sigmoid colon | 5 cm pelvic mass involving mucosa, muscularis and adjacent peritoneum | Local (peritoneum) | No | Laparoscopic AR - > Hormonal therapy |

NED 4 y |

| Biliatis et al. [2] | 56 | None | Incidental finding of a pelvic mass at pelvic US | Terminal ileum, cecum | 8 × 7 × 6 cm mass invading serosa | None | Yes | Rt. Hemicolectomy, TAH, BSO, bilateral pelvic node resection, omentectomy - > Chemotherapy - > Hormonal therapy |

NED 38 mo |

| Rosca et al. [11] | 51 | Removal of endometriosis implants from ovaries and rectum |

NA | Sigmoid, Appendix (2 m later) |

5 cm mass 3 cm peri-appnedicular mass |

Local | Yes | Resection Details NA |

Recurrence 2 mo Long term − NA |

| Doghri et al. [13] | 45 | None | Abdominal discomfort (6 mo) |

Omentum | 35 × 28 × 18 cm mass involving omentum | None | Yes | Tumourectomy and omentectomy | NA |

| Zemlyak et al. [12] | 70 | TAH, BSO (leiomyoma) Endometriosis HRT |

Abdominal pain and increased urinary frequency | Sigmoid colon, terminal ileum | 15.8 × 13 × 8.9 cm mass adherent to both bowel segments and left ureter | None | Yes | Sigmoidectomy and segmental resection of terminal ileum | NED 3 yr |

| Kim et al. [1] | 75 | TAH, BSO (leiomyomas) | Abdominal pain and palpable mass (1 yr) | Jejunum, mesentery and omentum | 7 cm mass adherent to jejunal serosa. 4.5 cm mass in jejunal lumen. 03.-0.5 cm nodules on mesentery and omentum. |

Local (mesentery,omentum) | No | Segmental resection of jejunum and omentectomy Refused chemotherapy |

Recurrence 5 mo repeated surgery, no further F/U |

| Chen et al. [8] | 42 | Non-small cell lung cancer, chemotherapy Treatment (5 yr) |

Difficult defecation and hematochezia (1 mo) |

Sigmoid colon and omentum | 1–3 cm nodular masses involving bowel wall from mucosa to peri-colic fat | Local (omentum, ovary, fallopian tubes) | Yes | Rectosigmoidectomy, TAH, BSO, partial omentectomy -> Radiotherapy |

NED 12 mo |

| Kovac et al. [22] |

45 | TAH, RSO (leiomyoma, normal adnexa) | Symptoms of stenosing process | Rectosigmoid and omentum | 6 cm mass infiltrating all layers of bowel wall and multiple omental nodules | Local (omentum, ovary) | Yes | Tumourectomy, colon resection, LSO, omentectomy | NED 11 mo |

| Rojas et al. [10] | 42 | None | Diarrhea (2 yr) Acute abdominal pain, small bowel obstruction (1 d) | Small bowel, mesentery | 2.5–3.5 cm multiple nodules | Distant (bowel mesentery) | Yes | Laparoscopy, 3 nodules resected for histology. No definite surgery described. | NA |

| Cho et al. [9] | 48 | Subtotal hysterectomy (leiomyoma) TAH, BSO (endometriosis) |

Difficult defecation and tenesmus | Sigmoid colon | 1–3 cm multi-multinodular masses involving all layer of bowel wall | Local (bowel, bladder, ureter) | Yes | Segmental sigmoid resection, regional LNs dissection | DIC post surgery NED 4 mo |

| Bosincu et al. [14] | 42 | None | Abdominal pain and fever | Rectosigmoid | Multiple polypoid ulcerated masses with transmural infiltration of bowel wall (size NA) | Local (omentum, peritoneum, parametrium, paracolic LNs) | Yes | AR, appendectomy, omentectomy, TAH, BSO -> Chemotherapy |

NED 20 mo |

| Mourra et al. [17] | 61 | HRT | Epigastric pain (portal vein thrombosis on US) | Rectosigmoid | 2.7 cm polypoid tumour with lumen stenosis, involving all layers of bowel wall | None | Yes | LAR | NED 30 mo |

| Yantiss et al. [18] | 63 | NA | NA | Rectum | 2 cm polypoid mass involving all layers of bowel wall with lumen stenosis | None | Yes | Rectal resection (not specified) | Recurrence 3y. NED at 6y following radiotherapy |

| Fukunaga et al. [23] | 43 | None | Abdominal distention (1 mo) |

Rectum, bladder | 14 × 12 × 10 cm ill-circumscribed mass adherent to rectum and bladder wall | None | Yes | Tumourectomy, partial resection of rectal wall, TAH, BSO | NED 39 mo |

| Fukunaga et al. [23] | 50 | None | Abdominal distension | Omentum, transverse colon mesentery | 20 cm omental mass, 10 cm mesocolon mass | Local (mesentery) | No | Tumourectomy, partial resection of transverse colon | NED 18 mo |

| Baiocchi et al. [16] | 38 | Ovarian Cystectomy (endometriosis) TAH, BSO (menorrhagia) |

Abdominal and back pain (6 mo) |

Transverse and ascending colon, terminal ileum | Large multilobular mass adherent to colon and ileum, with scattered implants (size NA) | Distant (falciform ligament, gastrocolic ligament mesentery, pelvis) | Yes | Colectomy (ascending and transverse colon), partial ileum resection -> Chemotherapy -> Hormonal therapy |

NED 2y |

| Present case | 47 | TAH (menorrhagia) HRT |

Acute RLQ abdominal pain | Omentum | 2.1 cm tumour embedded in omentum | None | No | Laparoscopic resection of tumour, BSO -> Hormonal therapy |

NED 6 mo |

TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy; BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; RSO, rt. salpingo-oophorectomy; HRT, hormonal replacement therapy; NA, not available; NED, no evidence of disease; DOD, dead of disease.

Patient ages ranges between 38–80 years (median, 47.5 years). More than half of the patients were in their fifth decade or early menopause years (11/20) as previously reported [3]. The clinical presentation was ambiguous in most instances. The commonest complaint was abdominal pain (9 cases). Other complaints included hematochezia (4 cases) [5], [6], [7], [8], change in bowel habits (4 cases) [5], [6], [8], [9], and tenesmus (1 case) [9]. Only 2 cases, including the current one, presented acutely and were diagnosed following an emergent surgical intervention [10]. Associated foci of endometriosis was found in proximity to the tumour in 16 out of 20 patients, but only 3 of the 16 had documented history of endometriosis [9], [11], [12]. One patient had past endometriosis but none was found near the tumour [7]. The rectosigmoid was the most common site for primary EESS (12/20). Solitary involvement of the omentum is rare and was reported only in one case report prior to ours [13]. Lesions in the gastrointestinal tract may involve the serosa (9 cases) or invade bowel wall to create polypoid lesions [14], with resulting carcinoma-like obstructive symptoms (8 cases). Only four patients presented with disseminated disease [6], [10], [15], [16], while localised lesion or local spread comprised the majority of cases (9 and 7 cases respectively). Eight women had previous hysterectomy for benign pathologies, and four received unopposed hormonal therapy at the time of diagnosis, including the present case [7], [12], [17].

The association of EESS with endometriosis provides a clue for the pathogenesis of this tumour. Malignant transformation of endometriosis is a rare but recognised phenomenon, and was demonstrated by Yantiss et al. who reviewed 17 cases of pre-malignant and malignant transformation of gastrointestinal endometriosis [18]. Most malignant tumours were endometrial adenocarcinomas (8 cases), with one case of EESS. The high prevalence of concomitant endometriosis may have a bearing on the transformation pathway for EESS [3]. The pathogenesis of EESS in the absence of ectopic endometrial stroma is more obscure. Possible explanations include gland-poor endometriosis foci (stromal endometriosis) or complete replacement by the tumour [3]. Another theory is de-novo malignant transformation of peritoneum or coelomic multipotential epithelial cells [1], [3], [19].

Unopposed hormonal therapy is associated with endometrial carcinomatosis and is related to EESS as well [18]. Masand et al. found that the majority of postmenopausal women diagnosed with EESS and associated endometriosis were on long standing HRT [3]. In the present review four women received HRT, including the present case. Associated endometrial foci were found in two of those cases. No endometriosis was found in the third case, although there was a clinical history of endometriosis. The present case had neither past endometriosis nor pathological evidence of it in the resected specimen. This is the only reported case with EESS on the background of prolonged HRT without history or clinical presence of endometriosis. These findings suggest that HRT may be an independent risk factor for development and/or progression of EESS [3], [18].

Diagnosis of primary EESS needs exclusion of a uterine primary. In women with previous hysterectomy for benign pathologies, it is crucial to review previous specimens and rule out a missed uterine primary. The main differential diagnosis for EESS when arising from bowel is some other mesenchymal tumours, especially gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs). Spindle cells in EESS are characterised by monotonous arrangement, compared with sheets or fascicles arrangement in GIST. Proliferation of small arterioles, resembling spiral arterioles of the endometrium, is also typical of EESS. However, the final diagnosis, especially in cases of unusual tumour location and absence of endometriosis, depends on immunohistochemistry. Positive labelling for CD10, PR and ER with no reactivity for CD117 and CD34 confirms the diagnosis [1], [3], [20].

Although EESS was previously believed to have worse prognosis than its uterine counterpart [21], accumulating evidence, does not support this. Most cases reviewed had multifocal disease, with either local or distant dissemination, while only one death was reported for a patient with unresectable low grade EESS [6]. The clinical behaviour of EESS is similar to low grade uterine ESS. Mitotic index, size, multifocality, and vascular invasion, the known predictors for worse prognosis, do not affect the patients’ outcomes. The only feature that may predict poorer prognosis is high grade histologic features namely de-differentiation or cytologic atypia. This includes loss of typical vascular pattern, pleomorphic spindle or epitheloid cells, in concurrence with brisk mitotic activity [3].

Given the rarity of EESS, the treatment is usually based on the guidelines for uterine ESS. Surgical resection with or without debulking is the cornerstone of EESS treatment. Total abdominal hysterectomy and BSO is often added in order to rule out uterine or ovarian primary. The value of adjuvant therapy is not clear, as no prospective studies exist. Treatment options include observation only, hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or combined modality treatment. Hormonal therapy is the most prevalent treatment, and was also the chosen treatment for the present case [3], [12], [20].

4. Conclusion

EESS can occur without endometriosis and HRT may be an independent aetiological factor. The condition can mimic a chronic or acute abdominal pathology and laparoscopic core biopsy is the best way to achieve a diagnosis and formulate management.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Funding

This Research did no receive and specific grant form funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

The paper is a case report, and therefore does not require ethics approval.

Consent

Informed consent has been obtained from the patient, and all identifying details have been omitted.

Author contributions

Vered Buchholz – Conception of study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article

George Kiroff – Acquisition of data, management of case, revision of article.

Markus Trochsler – Acquisition of data, management of case, revision of article.

Harsh Kanhere – Analysis of data, revision of article, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Guarantor

Dr. Harsh Kanhere.

References

- 1.Kim L., Choi S.J., Park I.S., Han J.Y., Kim J.M., Chu Y.C., Kim K.R. Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the small bowel. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2008;12:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biliatis I., Akrivos N., Sotiropoulou M., Rodolakis A., Simou M., Antsaklis A. Endometrial stromal sarcoma arising from endometriosis of the terminal ileum: the role of immunohistochemistry in the differential diagnosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2012;38:899–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masand R.P., Euscher E.D., Deavers M.T., Malpica A. Endometrioid stromal sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013;37:1635–1647. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Son H.-J., Kim J.-H., Kang D.-W., Lee H.-K., Park M.-J., Lee S.Y. Primary extrauterine endometrial stromal sarcoma in the sigmoid colon. Ann. Coloproctol. 2015;31:68–73. doi: 10.3393/ac.2015.31.2.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Q., Zhao X., Han P. Endometrial stromal sarcoma arising in colorectal endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/534273. 534273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayuso A., Fadare O., Khabele D. A case of extrauterine endometrial stromal sarcoma in the colon diagnosed three decades after hysterectomy for benign disease. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;2013(202458) doi: 10.1155/2013/202458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C.-W., Ou J.-J., Wu C.-C., Hsiao C.-W., Cheng M.-F., Jao S.-W. High-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma arising from colon endometriosis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1551–1553. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho H.-Y., Kim M.-K., Cho S.-J., Bae J.-W., Kim I. Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the sigmoid colon arising in endometriosis: a case report with a review of literatures. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2002;17:412–414. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.3.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rojas H., Wang J., Chase D., Wang J. Pathologic quiz case: a 46-year-old woman with 1-day history of abdominal pain and intestinal obstruction. Extrauterine low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2005;129:e44–e46. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-e44-PQC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roşca E., Venter A., Muţiu G., Drăgan A., Coroi M., Roşca D.M. Endometrial stromal sarcoma developed on outer endometriosis foci. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. Rev. 2011;52:489–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zemlyak A., Hwang S., Chalas E., Pameijer C.R.J. Primary extrauterine endometrial stromal cell sarcoma: a case and review. J. Gastrointest. Cancer. 2008;39:104–106. doi: 10.1007/s12029-009-9064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doghri R., Mrad K., Driss M., Sassi S., Abbes I., Dhouib R., Hechiche M., Romdhane K.B. Endometrial stromal sarcoma presenting as a cystic abdominal mass. Pathologica. 2009;101:93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosincu L., Massarelli G., Cossu Rocca P., Isaac M.A., Nogales F.F. Rectal endometrial stromal sarcoma arising in endometriosis: report of a case. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2001;44:890–892. doi: 10.1007/BF02234715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosal T., Roy A., Kurian S. Primary extrauterine endometrial stromal sarcoma: located in pelvic and abdominal tissue and arising in endometriosis. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2014;57:447–449. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.138757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baiocchi G., Kavanagh J.J., Wharton J.T. Endometrioid stromal sarcomas arising from ovarian and extraovarian endometriosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Gynecol. Oncol. 1990;36:147–151. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mourra N., Tiret E., Parc Y., de Saint-Maur P., Parc R., Flejou J.F. Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the rectosigmoid colon arising in extragonadal endometriosis and revealed by portal vein thrombosis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2001;125:1088–1090. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-1088-ESSOTR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yantiss R.K., Clement P.B., Young R.H. Neoplastic and pre-neoplastic changes in gastrointestinal endometriosis: a study of 17 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2000;24:513–524. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200004000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katre R., Morani A.K., Prasad S.R., Surabhi V.R., Choudhary S., Sunnapwar A. Tumors and pseudotumors of the secondary müllerian system: review with emphasis on cross-sectional imaging findings. AJR Am J. Roentgenol. 2010;195:1452–1459. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rauh-Hain J.A., del Carmen M.G. Endometrial stromal sarcoma: a systematic review. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;122:676–683. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a189ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang K.L., Crabtree G.S., Lim-Tan S.K., Kempson R.L., Hendrickson M.R. Primary extrauterine endometrial stromal neoplasms: a clinicopathologic study of 20 cases and a review of the literature. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 1993;12:282–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kovac D., Gasparović I., Jasic M., Fuckar D., Dobi-Babić R., Haller H. Endometrial stromal sarcoma arising in extrauterine endometriosis: a case report. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2005;26:113–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fukunaga M., Ishihara A., Ushigome S. Extrauterine low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: report of three cases. Pathol. Int. 1998;48:297–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1998.tb03909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]