Abstract

Despite the tremendous achievement in reducing child mortality and morbidity in the last two decades, diarrhoea is still a major cause of morbidity and mortality among children in many developing countries, including Ethiopia. Hand washing with soap promotion, water quality improvements and improvements in excreta disposal significantly reduces diarrhoeal diseases.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of hand washing with soap and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) educational Intervention on the incidence of under-five children diarrhoea. A community-based cluster randomized controlled trial was conducted in 24 clusters (sub-Kebelles) in Jigjiga district, Somali region, Eastern Ethiopia from February 1 to July 30, 2015. The trial compared incidence of diarrhoea among under-five children whose primary caretakers receive hand washing with soap and water, sanitation, hygiene educational messages with control households. Generalized estimating equation with a log link function Poisson distribution family was used to compute adjusted incidence rate ratio and the corresponding 95% confidence interval.

The results of this study show that the longitudinal adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) of diarrhoeal diseases comparing interventional and control households was 0.65 (95% CI 0.57, 0.73) suggesting an overall diarrhoeal diseases reduction of 35%. The results are similar to other trials of WASH educational interventions and hand washing with soap.

In conclusion, hand washing with soap practice during critical times and WASH educational messages reduces childhood diarrhoea in the rural pastoralist area.

Keywords: Hand washing with soap, WASH, Education, Childhood diarrhoea, Somali region, Jigjiga, Eastern Ethiopia; Trial Registration: ClinicalTrial.gov: NCT02779010

Highlights

-

•

Childhood diarrhoea is the third leading cause of mortality in low income countries.

-

•

A community based RCT was conducted in the pastoralist Somali region of Ethiopia.

-

•

Intervention was hand washing with soap and WASH educational key messages.

-

•

Longitudinal adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) of diarrhoea was 0.65 (95% CI 0.57).

-

•

Intervention reduced childhood diarrhoea by 35% compared to controls communities.

1. Introduction

The deadline of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) has just expired in 2015. The target for MDG 4 was to reduce the under-5 mortality rate by two-thirds between 1990 and 2015. This goal called for two-thirds reduction in mortality in children younger than five years between 1990 and 2015 (UN, 2000).

Since then, between 1990 and 2012, worldwide mortality in children younger than 5 years has declined by 47%, from an estimated rate of 90 deaths per 1000 live births to 48 deaths per 1000 live births. This translates into 17,000 fewer children dying every day in 2012 than in 1990 (WHO, 2015). The 2014 report of the United Nations Inter-Agency Group for mortality estimated that under-five mortality decreased by 69% from 205 deaths per 1000 live births in 1990 to 64 in 2013, outpacing the MDG 4 target of a two-thirds reduction (Alkema et al., 2014).

In Ethiopia between 2000 and 2016 under-five children mortality have decreased remarkably by 60% from an estimated rate of 166 to 67 deaths per 1000 live births (CSA and ICF, 2016).

However, mortality rates for children under-five remains high. Recent evidence showed that 6.3 million children died before age 5 years in 2013. Among these, 51.8% (3.257 million) died of infectious causes. If present trends continue, 4.4 million children younger than 5 years will die in 2030. Furthermore, sub-Saharan Africa will have 33% of the births and 60% of the deaths in 2030, compared with 25% and 50% in 2013 respectively (Liu et al., 2015). In Ethiopia, despite the sharp decrease in under-five mortality, regional variation exist within the country and Somali region has under-five mortality of 122 deaths per 1000 live births (CSA, 2012).

Infectious diseases reductions significantly reduce childhood deaths. Reductions in pneumonia, diarrhoea, and measles collectively were responsible for half of the 3.6 million fewer deaths recorded in 2013 versus 2000 (Liu et al., 2015).

Childhood diarrhoea is the third leading cause of mortality in low income countries including Ethiopia, causing an estimated 1.4 million deaths in 2012 (WHO, 2015, Forouzanfar et al., 2015). Young children are especially vulnerable, with diarrhoea accounting more than one quarter of all deaths in children aged under-five years in Africa and South East Asia (Murray et al., 2013, Lanata et al., 2013, Walker et al., 2013, Boschi-Pinto et al., 2008).

Diarrhoeal disease risk reductions of 48%, 17% and 36% is associated respectively with hand washing promotion, water quality improvements and improvements in excreta disposal (Cairncross et al., 2010). WASH interventions averted 13% of childhood deaths in Ethiopia in 2011 (Doherty et al., 2016).

Water from improved source isn't always safe (WHO, 2012) and may be contaminated with pathogens during transportation and storage (WHO, 2007). Estimates of the health impact of WASH interventions on under-five children are derived from interventions that promote or improve domestic services and practices in the environment (Cairncross et al., 2010).

Moreover, hand washing with soap can reduce micro-organism level close to zero and can interrupt the transmission of faecal-oral microbes in the domestic environment (Kampf and Kramer, 2004, Sprunt et al., 1973) mainly through the mechanics of rubbing and rinsing (Sprunt et al., 1973, Lowbury et al., 1964).

The effect of hand washing with soap practices and WASH educational interventions on childhood diarrhoea in the rural settings of the Sub-Saharan Africa remains unexplored, although it was done in Asia three decades ago (Stanton and Clemens, 1987). Interventional studies have covered the transfer of knowledge about proper hygiene but from school settings (Bowen et al., 2007, Blanton et al., 2010, Dreibelbis et al., 2014).

We evaluated the effect of hand washing with soap practice and WASH educational intervention on childhood diarrhoeal diseases incidence in the rural pastoralist community settings of Somali region, Eastern Ethiopia.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics statement

The study protocols have been reviewed and approved by the Jigjiga University ethical review committee. Study consent was obtained from district administration, district health office and community leaders. Control clusters in the sub-Kebelle have received free books and pencils to support their children's education during the study period and after completion of the study, they were given the same health education sessions used in this study. Written consent was taken from the primary caretakers of the children.

2.2. Study setting

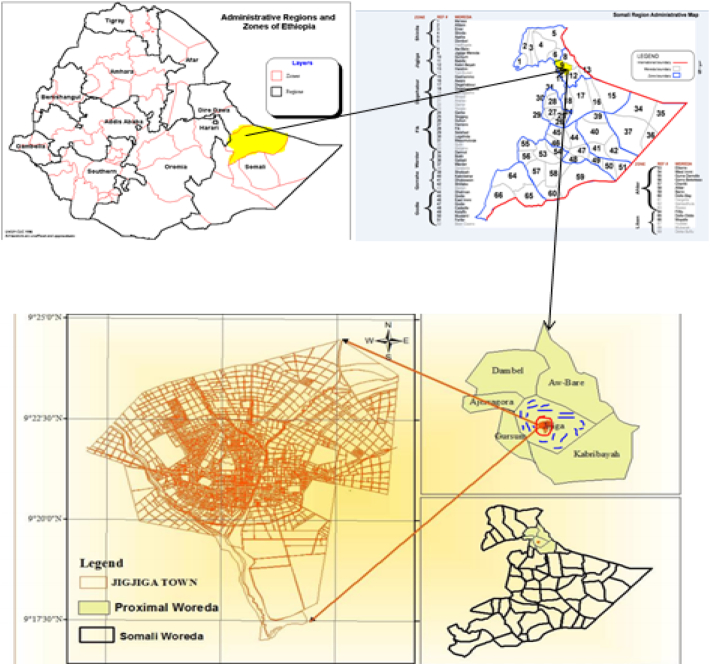

The current study was conducted in the rural areas of Jigjiga district of Ethiopian-Somali Regional State (ESRS) in the Eastern Ethiopia from February 1 to July 30, 2015. The ESRS is one of the nine regional states that constitute the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Pastoralism is a way of life whereby the livelihood of the people depends on raising livestock and living on its milk and meat (Montavon et al., 2013). Nearly 90% of the population in ESRS resides in rural areas, leading either a pastoralist or agro-pastoralist lifestyle. Jigjiga district is one of the 68 districts of the region, part of Fafan zone, with a total population of 277,560 according to 2007 census conducted by the central statistical agency of Ethiopia of whom 149,292 are men and 128,268 women. A total of 34 Kebele is found in the district of which 4 are urban and 30 are rural Kebele in the Woreda (Fig. 1). Finally Jigjiga district was selected for the study because of acute watery diarrhoea outbreaks as reported by the Regional Health Bureau.

Fig. 1.

Map of Jigjiga Woreda; part of the map adopted from (Berisa and Birhanu, 2015). Red-circle indicates Jigjiga city while blue-lines represent Kebelles of Jigjiga district.

2.3. Sample size determination

The sample was calculated by using methods published by Hayes and Bennett (1999). A recent study conducted in Eastern Ethiopia indicated disease rates for incidence of child diarrhoea among home based chlorine treatment intervention group of 4.5 episodes/100 person week observations (Mengistie et al., 2013). Using this incidence, along with 80% power and 95% confidence interval, we randomly selected a final sample of 24 clusters (12 for the intervention group and 12 for the control group) with 50 children of under-five in each cluster.

2.4. Study design and eligibility criteria

A community-based cluster randomized controlled trial was employed. The study groups were divided into two: clusters that received intervention and control clusters. Only rural communities of the district were selected for the study. A household was considered eligible for the study if the following criteria are met: a) at least one child aged 1–59 months living in the home and b) not a model health extension household. Households that successfully implement all components of the 16 packages of the Health Extension Program (HEP) are officially certified as a Model Health Extension Household (Teklehaimanot et al., 2007). This trial excludes all model Health Extension households to avoid biases due to a competing intervention.

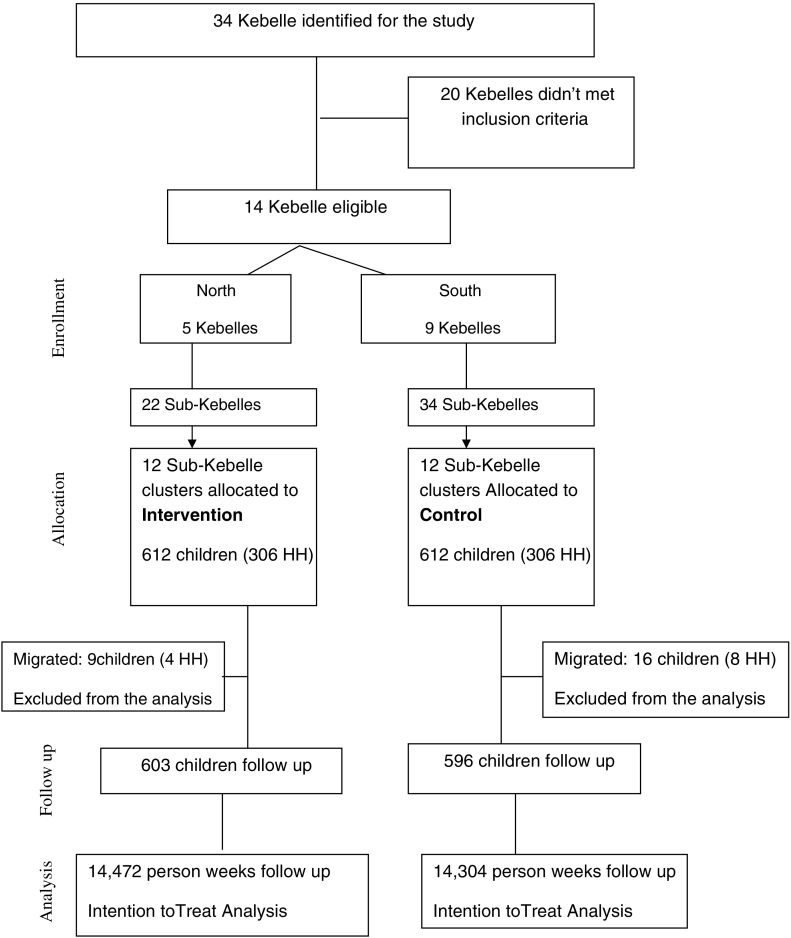

2.5. Randomization and masking

Kebelle is the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia consisting of at least 500 households, or the equivalent of 3500 to 4000 persons (FMOH, 2007). The Kebelle is further divided into sub-Kebelles (neighbourhood villages). A Final count of 14 Kebelle was eligible for the study. These eligible Kebelles for the study located north and south of Jigjiga City i.e., 5 North (22 sub-Kebelles) and 9 South (34 sub-Kebelles). Eligible Kebelles in the north and south were assigned randomly to intervention and control groups respectively by using lottery method in the presence of community leaders, Kebele heads and representative from the district health office and Regional Health Bureau to avoid study contamination by geographically separating the region of the intervention from the control region. Twenty-four Sub-Kebelles were then randomly selected from the 56 total sub-Kebelles by using simple randomization (computer generated numbers). From 22 sub-Kebelles, 12 were selected randomly and assigned to the Intervention group. From 34 sub-Kebelles, 12 were selected randomly and assigned to the control group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Community randomized trial flow of participants on WASH educational intervention: Jigjiga district, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2015.

HH = House holds.

Neither the community (both control and intervention group) nor the field workers knew the intervention purpose. The follow up study started on February 1, 2015 and ended July 30, 2015.

2.6. Intervention

Twelve sessions of health education on key WASH messages and demonstration of hand washing with soap were given to all of the intervention clusters by clinical nurse professionals (field workers) who have taken training for 10 days. Primary care takers of the children in the households were instructed to keep their water storage container clean and covered, to have a latrine and utilize properly, and to wash their hands and children's hands ideally with soap after defecation, before meal preparation and eating.

The field workers arranged cluster (Sub-Kebelle) meetings for each cluster to illustrate the pamphlets, show health problems resulting from hand and water contamination and showed specific instruction on how to use the intervention assigned to the cluster. Intervention happened every 2 weeks in a period of 6 months follow up. Each intervention took up to 3-hour time from 4:00 pm to 7:00 pm local time since most village residents were available in late afternoon.

All households in the intervention clusters received a package of health education messages and soap (white bars). The field workers demonstrated by face to face approach how to wet their hands, lather them completely with soap, and rub together for 1 min. The other key messages were provided by using loudspeaker (Megaphone) at one time in each visit at the respective cluster location.

Primary care takers of the control group continued their way of hand washing practices, disposal of water storage behaviour and latrine sanitation. After the completion of the study they were given the same educational intervention used in this study. Table 1 illustrates key messages and interventions used in this study.

Table 1.

Key messages and WASH interventions used in this study, Jigjiga district, 2015.

| Intervention | Key messages | Method | Tools used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hand washing with soap and water |

|

Demonstration Pamphlets |

Water and white bar soap |

| Water storage behaviour related messages |

|

Instruction | Locally available Jericans were used as demonstration |

| Latrine availability and utilization messages |

|

Demonstration Instruction |

|

| Safe waste disposal messages |

|

Demonstration Instruction |

2.7. Data collection and outcome assessment

The primary outcome was longitudinal incidence of diarrhoea. In this study diarrhoea is defined as the passage of three or more liquid or semi-liquid stools in a 24-hour period or the passage of at least one liquid or semi-liquid stool with blood or mucus (Baqui et al., 1991). This definition of diarrhoea was being instructed to the primary care takers by the data collectors. Primary care takers were also instructed to follow the child and report diarrhoea in the previous two weeks. Twenty-four data collectors (field workers) visited intervention and control households in every 2 weeks period (12 visits). At each visit, occurrence of diarrhoea (episodes of diarrhoea) over the previous two weeks was recorded by the data collectors for all under-five children based on the primary care taker report.

The secondary outcome was bacteriological quality of drinking water at household level. Water samples (100 ml) were collected from all households' drinking water storage container by asking the primary care takers to provide water from the containers for the researchers. The guideline of WHO for drinking water quality assessment was used as a method of water sample collection at each household (WHO, 2004). The collected water samples from each source was labelled and kept in icebox during transportation and analysed in the laboratory. All collected samples were analysed for the presence of faecal coliform.

A baseline survey was conducted on primary care takers, children, environmental characteristics and pre-intervention diarrhoea prevalence rates by using questionnaire.

2.8. Data analysis

The data was cross checked by the field supervisors on a visit basis. Prior to data entry, base line and follow up visit data forms were checked for completeness and consistence. Data was double entered on to EPI data Version 3.5.3 and statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS version 20. Intention-to-treat analysis was used to compare the incidence of diarrhoea among under-five children between intervention and control arms.

The baseline data was analysed and compared among the intervention and control group. The rate of diarrhoea (per 100 person-weeks) in children under-five years of age was measured for the intervention and control communities. Generalized estimating equation (Zeger and Liang, 1986) with log link Poisson distribution family was used to compute adjusted incidence rate ratio and the corresponding 95% confidence interval of the dependent variable (longitudinal incidence of diarrhoea) and co-variates. For the water quality, water samples were analysed for the presence of faecal coliforms and compared among the intervention and control communities.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

At baseline assessment 612 households were interviewed in January 15–25, 2015. The household, primary care takers, children and environmental characteristics were generally similar across intervention and control households and well balanced. The number of households and children per cluster were 25 and 50 respectively. The mean age of the mothers/caretakers was 28.5 for the intervention group and 29.7 for the control group and for the children 21.3 and 21.5 months in the intervention and control respectively. Pre-intervention two week diarrhoea prevalence was 26.5% for the control households and 23.2% for the intervention households (Table 2)).

Table 2.

Base line characteristics of community and household of the randomized cluster trial: Jigjiga district, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2015.

| Variable | Control N (Percent %) | Intervention, N (percent %) |

|---|---|---|

| Household information | ||

| Number of clusters | 12 | 12 |

| Number of households | 306 | 306 |

| Number of household per cluster | 25 | 25 |

| Number of under five children per cluster | 50 | 50 |

| Number of under-five children | 612 | 612 |

| Mean (SD) family size per household | 4.45 (1.85) | 4.89 (2.33) |

| Mean age of the child in months | 21.5 | 21.3 |

| Mothers/caretakers characteristics | ||

| Mean age | 28.5 | 29.7 |

| Mothers education | ||

| No formal education | 173 (56.5) | 149 (48.7) |

| Primary education | 121 (39.5) | 134 (43.8) |

| Secondary education | 10 (3.3) | 18 (5.9) |

| More than secondary education | 2 (0.7) | 5 (1.6) |

| Mothers marital status | ||

| Married | 265 (86.6) | 266 (86.9) |

| Divorced | 38 (12.4) | 35 (11.4) |

| Widowed | 3 (1.0) | 5 (1.6) |

| Occupation | ||

| House wife | 264 (86.3) | 249 (81.4) |

| Others | 42 (13.7) | 57 (18.6) |

| Fathers occupation | ||

| Livestock | 142 (49.8) | 130 (43.3) |

| Farmer | 108 (37.9) | 120 (40) |

| Merchant | 19 (6.7) | 23 (7.7) |

| Government employee | 16 (5.6) | 22 (7.3) |

| No job | – | 3 (1.0) |

| Others | – | 2 (0.7) |

| Mothers/caretakers diarrhoea | ||

| Yes | 57 (18.6) | 50 (16.3) |

| No | 249 (81.4) | 256 (83.7) |

| Child characteristics (N = 612) | ||

| Child age | ||

| < 12 months | 233 (39.1) | 242 (40.1) |

| 12–24 months | 175 (29.4) | 184 (30.5) |

| 24–59 months | 188 (31.5) | 177 (29.4) |

| Child gender | ||

| Male | 325(54.5) | 344 (57.0) |

| Female | 271 (45.5) | 259 (43.0) |

| Birth order | ||

| First order | 166 (27.9) | 171 (28.4) |

| Second order | 289 (48.5) | 284 (47.1) |

| Third order | 141 (23.7) | 148 (24.5) |

| Breastfeeding status | ||

| Exclusive | 119 (38.9) | 126 (41.2) |

| Partial | 177 (57.8) | 150 (49.0) |

| Not breastfed | 10 (3.3) | 30 (9.8) |

| Water, hygiene and sanitation indicators | ||

| Drinking water source | ||

| Protected source | 131 (42.8) | 146 (47.7) |

| Unprotected source | 175 (57.2) | 160 (52.3) |

| Water storage material | ||

| Jericans | 224 (73.2) | 217 (70.9) |

| Pot | 74 (24.2) | 77 (25.2) |

| Plastic container | 8 (2.6) | 12 (3.9) |

| Latrine availability | ||

| Yes | 146 (47.7) | 183 (59.8) |

| No | 160 (52.3) | 123 (40.2) |

| Waste water disposal site availability | ||

| Yes | 173 (56.5) | 147 (48.0) |

| No | 133 (43.5) | 159 (52.0) |

| Solid waste disposal site availability | ||

| Yes | 152 (49.7) | 155 (50.7) |

| No | 154 (50.3) | 151 (49.3) |

| Hand washing at critical points | ||

| Yes | 147 (48.0) | 145 (47.4) |

| No | 159 (52.0) | 161 (52.6) |

| Hand washing site in the latrine | ||

| Yes | 133 (43.5) | 113 (36.9) |

| No | 173 (56.5) | 193 (63.1) |

| Two-week prevalence of diarrhoea | ||

| Yes | 81 (26.5) | 71 (23.2) |

| No | 225 (73.5) | 235 (76.8) |

3.2. Longitudinal incidence of diarrhoea

The incidence of diarrhoea was significantly lower among under-five children from the intervention households. From the control arm 905 occurrences (episodes) of diarrhoea (6.3 episodes per 100 person-weeks observation) were reported. Intervention households reported 594 episodes (4.1 episodes per 100 person-weeks observation) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of the intervention with different age groups of under-five children of randomized cluster trial: Jigjiga district, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2015.

| Age group | Control group (N = 596) |

Intervention group (N = 603) |

% of reduction | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of DD episode | PWO | DD incidence | Number of DD episode | PWO | DD incidence | |||

| < 12 months | 358 | 5592 | 6.4 | 251 | 5808 | 4.3 | 33 | < 0.01 |

| 12–24 months | 262 | 4200 | 6.2 | 192 | 4416 | 4.3 | 31 | < 0.01 |

| 24–59 months | 285 | 4512 | 6.3 | 151 | 4248 | 3.5 | 44 | < 0.01 |

| All < 5 years | 905 | 14,304 | 6.3 | 594 | 14,472 | 4.1 | 35 | < 0.01 |

DD = Diarrhoeal disease, PWO = person-week observation, DD incidence is number of DD episodes/PWO per 100 person-weeks.

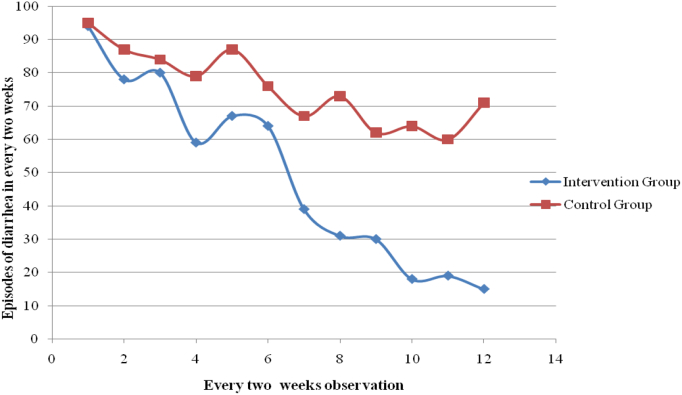

Sharp decrease of diarrhoea episodes per week among intervention households was observed during the course of this study. Fig. 3 shows the number of diarrhoea occurrence and the visit week.

Fig. 3.

Bi-weekly total episodes of diarrhoea versus weeks of observation of randomized cluster trial: Rural areas of Jigjiga district, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2015.

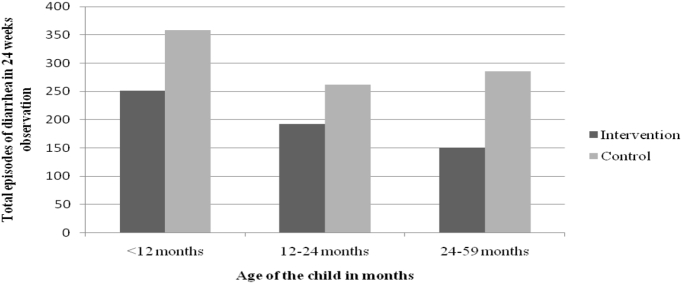

In both interventional and control households, in the follow up duration, the longitudinal episodes of diarrhoea was higher in children < 12 months. The reduction of diarrhoea episodes for all age group in the follow up duration between the control and intervention households is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Bi-weekly total episodes of diarrhoea versus age category of randomized cluster trial: Rural areas of Jigjiga district, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2015.

3.3. Household drinking water quality

There is a significant difference between the intervention and control households in the base-line and end-line water contamination. At base-line nearly 31% of the water was contaminated from the intervention households but in the end line assessment only 11% were contaminated from the intervention households (Table 4).

Table 4.

Household drinking water quality among intervention and control households at the base line and end line of the intervention: Jigjiga district, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2015.

| E. coli presence in the drinking water | Control | Intervention | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base line | 97 (31.7) | 94 (30.7) | 0.79 |

| After study completion | 142 (46.4) | 33 (10.8) | < 0.01 |

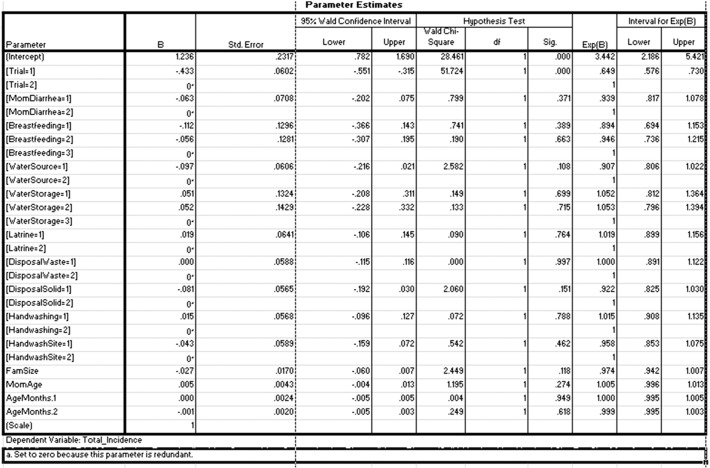

3.4. Multivariable analysis of intervention effect

Generalized estimating equation using log link function was used to control confounding factors that might have contributed to the incidence of diarrhoeal diseases. Socio-demographic characteristics, child, maternal factors and WASH related factors were checked if there is an association with the incidence of diarrhoea. The result shows that only the intervention contributes to the reduction of diarrhoea in the study area. See Table 5.

Table 5.

Multivariable analysis of intervention effect on the incidence of diarrhoeal among under-Five children, GEE using log link function: Jigjiga district, Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2015.

| Factors | Crude IRR (95% C.I) | Adjusted IRR (95% C.I) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 0.65 (0.58,0.72) | 0.65 (0.57,0.73) | < 0.01 |

| Control | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Family size | 0.97 (0.95,1.00) | 0.97 (0.94,1.01) | 0.11 |

| Child age | 1.00 (0.99,1.01) | 0.99 (0.99,1.00) | 0.62 |

| Mother/caretaker age | 1.00 (0.99,1.01) | 1.00 (0.99,1.01) | 0.27 |

| Mothers/care takers diarrhoea | |||

| Yes | 0.93 (0.81,1.08) | 0.94 (0.69,1.15) | 0.37 |

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Child breastfeeding | |||

| Exclusive | 0.93 (0.73,1.18) | 0.89 (0.69,1.15) | 0.38 |

| Partial | 1.00 (0.79,1.28) | 0.94 (0.74,1.21) | 0.66 |

| Not breastfed | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Water source | |||

| Protected source | 0.89 (0.79,1.01) | 0.91 (0.81,1.02) | 0.11 |

| Unprotected source | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Water storage | |||

| Jericans | 1.04 (0.81,1.35) | 1.05 (0.81,1.36) | 0.69 |

| Pot | 1.04 (0.79,1.38) | 1.05 (0.79,1.39) | 0.71 |

| Plastic container | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Latrine availability | |||

| Yes | 0.93 (0.83,1.04) | 1.02 (0.89,1.15) | 0.76 |

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Liquid waste disposal | |||

| Yes | 1.02 (0.91,1.14) | 1.00 (0.89,1.15) | 0.99 |

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Solid waste disposal | |||

| Yes | 0.91 (0.81,1.01) | 0.92 (0.82,1.03) | 0.92 |

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Hand washing at critical times | |||

| Yes | 0.98 (0.87,1.10) | 1.01 (0.91,1.13) | 0.78 |

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Hand washing site in the latrine | |||

| Yes | 0.95 (0.85,1.06) | 0.96 (0.85,1.07) | 0.46 |

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

IRR = Incidence Rate Ratio.

4. Discussion

The study assessed effect of hand washing with soap and WASH educational interventions on the incidence of childhood diarrhoea in the rural settings of Somali region. The study shown 35% reduction (RR = 0.65; 95% CI 0.57,0.73) in diarrhoeal diseases for households who practiced hand washing with soap and the WASH key messages compared to control households that were given no intervention. The result of the study is supporting one another. When exposure of continuous health education session was given consistently in six months period, longitudinal incidence of under-five children diarrhoea has decreased by 35%.

The importance of WASH educational interventions is stressed by reports that show that improvements in water supply in terms of quantity and quality and physical facilities for excreta disposal without adequate behavioural change among the target community alone would not change the prevalence of diarrhoeal diseases (Brown et al., 2013).

Although our study didn't compare effect of each intervention on the overall reduction, we believe that the WASH educational messages also led to behavioural changes among the target group which together reduced diarrhoeal diseases. Our result suggests the assumption that it was those combinations of hand washing with soap and key health education on WASH factors that reduced the incidence of diarrhoea on a weekly base as field workers continue visiting and instructing intervention households.

The result was consistent with other similar studies interventional study done on the subject WASH interventions (Blanton et al., 2010, Bowen et al., 2007, Luby et al., 2005, Luby et al., 2006, Freeman et al., 2012, Han and Hlaing, 1989, Aiello et al., 2008).

Limitation of this study includes randomization at the Sub-Kebelle level which resulted in a small number of clusters but the result can still be compared to other studies of WASH education and hand washing interventions.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contribution

All authors participated from the conception to the final write up of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express profound gratitude to the Ethiopian Institute of Water Resources, Addis Ababa University and University of Connecticut and USAID for their financial support. We are also thankful for the Ethiopian-Somali Regional Health Bureau, all the data collectors and study participants for their cooperation and facilitation of the data collection.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.04.011.

Contributor Information

Abdiwahab Hashi, Email: abdiwahab_2@yahoo.com.

Abera Kumie, Email: aberakumie2@yahoo.com.

Janvier Gasana, Email: Janvier.Gasana@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material 1

Supplementary material 2

Supplementary material 3

Supplementary material 4

Supplementary material 5

Supplementary material 6

Trial Protocol

References

- Aiello A.E., Coulborn R.M., Perez V., Larson E.L. Effect of hand hygiene on infectious disease risk in the community setting: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Public Health. 2008;98:1372–1381. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.124610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkema L., New J.R., Pedersen J., You D. Child mortality estimation 2013: an overview of updates in estimation methods by the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baqui A.H., Black R.E., Yunus M., Hoque A.R., Chowdhury H.R., RB S. Methodological issues in diarrhoeal diseases epidemiology: definition of diarrhoeal episodes. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1991;20:1057–1063. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.4.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berisa G., Birhanu Y. 2015. Municipal Solid Waste Disposal Site Selection of Jigjiga Town Using GIS and Remote Sensing Techniques. (Ethiopia) [Google Scholar]

- Blanton E., Ombeki S., Oluoch G.O., Mwaki A., Wannemuehler K., Quick R. Evaluation of the role of school children in the promotion of point-of-use water treatment and handwashing in schools and households—Nyanza Province, Western Kenya, 2007. Am.J.Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010;82:664–671. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschi-Pinto C., Velebit L., Shibuya K. Estimating child mortality due to diarrhoea in developing countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2008;86:710–717. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.050054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen A., Ma H., Ou J. A cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of a handwashing-promotion program in Chinese primary schools. Am.J.Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007;76:1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J., Cairncross S., Ensink J.H.J. Water, sanitation, hygiene and enteric infections in children. Global Child Health. 2013:629–634. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairncross S., Hunt C., Boisson S. Water, sanitation and hygiene for the prevention of diarrhoea. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2010;39:i193–i205. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CSA . Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA. Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) and ICF International; 2012. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2011. [Google Scholar]

- CSA E., ICF . Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA. CSA and ICF; 2016. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016: key indicators report. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty T., Rohde S., Besada D. Reduction in child mortality in Ethiopia: analysis of data from demographic and health surveys. J. Global Health. 2016;6 doi: 10.7189/jogh.06.020401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreibelbis R., Freeman M.C., Greene L.E., Saboori S., Rheingans R. Vol. 104. 2014. The Impact of School Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Interventions on the Health of Younger Siblings of Pupils: A Cluster-randomized Trial in Kenya; pp. 91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FMOH . Addis Ababa: Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. 2007. Health extension program profile in Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Forouzanfar M., Alexander L., Anderson H. GBD 2013 risk factors collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:2287–2323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M.C., Greene L.E., Dreibelbis R. Assessing the impact of a school-based water treatment, hygiene and sanitation programme on pupil absence in Nyanza Province, Kenya: a cluster-randomized trial. Tropical Med. Int. Health. 2012;17:380–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han A.M., Hlaing T. Prevention of diarrhoea and dysentery by hand washing. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1989;83:128–131. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90737-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes R.J., Bennett S. Simple sample size calculation for cluster-randomized trials. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1999;28:319–326. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampf G., Kramer A. Epidemiology background of hand hygiene and evaluation of the most important agents for scrubs and rubs. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004;17:863–893. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.863-893.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanata C.F., Fischer-Walker C.L., Olascoaga A.C., Torres C.X., Aryee M.J., Black R.E. Global causes of diarrheal disease mortality in children < 5 years of age: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Oza S., Hogan D. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385:430–440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowbury E.J., Lilly H.A., JP B. Disinfection of hands: removal of transient organisms. Br. Med. J. 1964;2:230–233. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5403.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby S.P., Agboatwalla M., Feikin D.R. Effect of handwashing on child health: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:225–233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66912-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby S.P., Agboatwalla M., Painter J. Combining drinking water treatment and hand washing for diarrhoea prevention, a cluster randomised controlled trial. Tropical Med. Int. Health. 2006;11:479–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengistie B., Berhane Y., Worku A. Household water chlorination reduces incidence of diarrhea among under-five children in rural Ethiopia: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montavon A., Jean-Richard V., Bechir M. Health of mobile pastoralists in the Sahel–assessment of 15 years of research and development. Tropical Med. Int. Health. 2013;18:1044–1052. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C.J., Vos T., Lozano R. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprunt K., Redman W., Leidy G. Antibacterial effectiveness of routine hand washing. Pediatrics. 1973;52:264–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton B.F., Clemens J.D. An educational intervention for altering water-sanitation behaviors to reduce childhood diarrhea in urban Bangladesh II. A randomized trial to assess the impact of the intervention on hygienic behaviors and rates of diarrhea. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1987;125:292–301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teklehaimanot A., Kitaw Y., G-Yohanne A. Study of the working conditions of health extension workers in Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 2007;23:246–259. [Google Scholar]

- UN U.G.A. United Nations General Assembly. 2000. United Nations millennium declaration. [Google Scholar]

- Walker C.L.F., Rudan I., Liu L. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet. 2013;381:1405–1416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2004. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Links to Health: Facts and Figures. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . International Network to Promote Household Water Treatment and Safe Storage. Geneva World Health Organization; 2007. Combating waterborne disease at the house-hold level. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva, Swizerland: 2012. Rapid Assessment of Drinking Water Quality: A Handbook for Implementation. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2015. World Health Organization. The Top 10 Causes of Death. Fact Sheet N°310. [Google Scholar]

- Zeger S.L., Liang K.-Y. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 3

Supplementary material 4

Supplementary material 5

Supplementary material 6

Trial Protocol