Abstract

Introduction

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) affect more than one billion people, mainly living in developing countries. For most of these NTDs, treatment is suboptimal. To optimize treatment regimens, clinical pharmacokinetic studies are required where they have not been previously conducted to enable the use of pharmacometric modeling and simulation techniques in their application, which can provide substantial advantages.

Objectives

Our aim was to provide a systematic overview and summary of all clinical pharmacokinetic studies in NTDs and to assess the use of pharmacometrics in these studies, as well as to identify which of the NTDs or which treatments have not been sufficiently studied.

Methods

PubMed was systematically searched for all clinical trials and case reports until the end of 2015 that described the pharmacokinetics of a drug in the context of treating any of the NTDs in patients or healthy volunteers.

Results

Eighty-two pharmacokinetic studies were identified. Most studies included small patient numbers (only five studies included >50 subjects) and only nine (11 %) studies included pediatric patients. A large part of the studies was not very recent; 56 % of studies were published before 2000. Most studies applied non-compartmental analysis methods for pharmacokinetic analysis (62 %). Twelve studies used population-based compartmental analysis (15 %) and eight (10 %) additionally performed simulations or extrapolation. For ten out of the 17 NTDs, none or only very few pharmacokinetic studies could be identified.

Conclusions

For most NTDs, adequate pharmacokinetic studies are lacking and population-based modeling and simulation techniques have not generally been applied. Pharmacokinetic clinical trials that enable population pharmacokinetic modeling are needed to make better use of the available data. Simulation-based studies should be employed to enable the design of improved dosing regimens and more optimally use the limited resources to effectively provide therapy in this neglected area.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40262-016-0467-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points

| Neglected tropical diseases affect a major part of the global population, but treatments have generally not been optimized. |

| We provide a comprehensive systematic overview of performed pharmacokinetic studies in all 17 neglected tropical diseases, advantages and drawbacks of different methodologies, and gaps in pharmacokinetic research through which neglected tropical diseases therapeutics can be further improved. |

| For most neglected tropical diseases, adequate pharmacokinetic studies were found lacking or completely absent, pediatric patients have largely been ignored, and population-based modeling and simulation techniques have not generally been applied. |

| To more optimally use the limited available resources in this neglected area, more emphasis should be given to simulation-based pharmacokinetic studies enabling the design of improved dosing regimens. |

Introduction

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) represent a wide range of infectious afflictions, which are prevalent mostly in tropical and subtropical countries and have one common characteristic: they all affect people living in deep poverty. All NTDs are heavily debilitating, causing life-long disability, which can be directly fatal if left untreated. At the moment, over 1.4 billion people are affected by at least one NTD, and they are the cause of death for over 500,000 people annually [1, 2]. There are currently 17 NTDs as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), which include protozoal, bacterial, helminth, and viral infections [1]. An overview of their transmission, geography, and burden of disease is provided in Table 1. Collectively, the NTDs belong to the most devastating of communicable diseases, not only in terms of global health burden (26.1 million disability-adjusted life-years) [3, 4], but also in terms of impact on development and overall economic productivity in low- and middle-income countries [3, 5].

Table 1.

Summary of neglected tropical diseases including endemic areas, causative agents, method of transmission, and estimated global burden expressed in deaths per year and DALYsa

| Disease | Endemic areas | Causative agents | Transmission | Deaths per year | DALYs in millions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protozoal infections | |||||

| Chagas disease | Latin America | Trypanosoma cruzi | Triatomine bug | 10,300 | 0.55 |

| Human African trypanosomiasis | Africa | Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, T. brucei rhodesiense | Tsetse fly | 9100 | 0.56 |

| Leishmaniasis | Indian subcontinent, Asia, Africa, Mediterranean basin, South America |

Visceral: Leishmania donovani, L. infantum

Cutaneous: L. major, L. tropica, L. braziliensis, L. mexicana and other Leishmania spp. |

Phlebotomine sandflies | 51,600 | 3.32 |

| Bacterial infections | |||||

| Buruli ulcer | Africa, South America, Western Pacific regions | Mycobacterium ulcerans | Unknown | n.d. | n.d. |

| Leprosy | Africa, America, South-east Asia, Eastern Mediterranean, Western Pacific | Mycobacterium leprae | Unknown | n.d. | 0.006 |

| Trachoma | Africa, Middle East, Mexico, Asia, South America, Australia | Chlamydia trachomatis | Direct or indirect contact with an infected person | - | 0.33 |

| Endemic treponematoses | Global distribution | Treponema pallidum, T. carateum | Skin contact | n.d. | n.d. |

| Helminthes | |||||

| Cysticercosis/taeniasis | Worldwide, mainly Africa, Asia, and Latin America | Taenia solium, Taenia saginata, diphyllobothrium latum | Ingestion of infected pork | 1200 | 0.5 |

| Dracunculiasis | Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, South Sudan | Dracunculus medinensis | Contaminated water | n.d. | n.d. |

| Echinococcosis | Global distribution | Echinococcus granulosus, Echinococcus multilocularis | Feces of carnivores | 1200 | 0.14 |

| Foodborne trematodiases | South-east Asia, Central and South America | Clonorchis spp., Opisthorchis spp., Fasciola spp., and Paragonimus spp., Echinostoma spp., Fasciolopsis buski, Metagonimus, Metagonimus spp., Heterophyidae | Contaminated food | - | 1.88 |

| Lymphatic filariasis | Africa, Asia, Central and South America | Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, B. timori | Mosquitos | - | 2.78 |

| Onchocerciasis | Africa, Latin America, Yemen | Onchocerca volvulus | Black flies | - | 0.49 |

| Schistosomiasis | Africa, South-America, Middle East, East-Asia, Laos, Cambodia | Schistosoma haematobium, S. guineensis, S. intercalatum, S. japonicum, S. mansoni, S. mekongi | Contaminated water | 11,700 | 3.31 |

| Soil-transmitted helminthiases | Global distribution | Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Necator americanus, Ancylostoma duodenale | Human feces | 2700 | 5.19 |

| Viral infections | |||||

| Dengue | Asian and Latin American countries | Dengue fever virus (genus: Flavivirus) | Mosquito | 14,700 | 0.83 |

| Rabies | Global distribution, mainly Africa, Asia, Latin America, and western Pacific | Rabies virus (genus: Lyssavirus) | Animals, mostly domestic dogs | 26,400 | 1.46 |

DALYs disability-adjusted life-years, n.d. not determined

aNumbers are based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010 [4]

The currently available treatments for NTDs are an outdated arsenal generally considered to be insufficient for NTD control and elimination [5]. Many of the currently available drugs were developed over 50 years ago and many of them exhibit high toxicity [5]. For example, the only available drug to treat late-stage human African trypanosomiasis (or sleeping sickness) caused by T. b. rhodesiense is melarsoprol, an arsenic compound, developed in the 1940s, which is itself lethal to 5 % of treated patients owing to post-treatment reactive encephalopathy [6]. In many regions, pentavalent antimony-containing compounds are still the treatment of choice for visceral leishmaniasis (VL) and cutaneous leishmaniasis, which have been in use since the 1930s. Therapeutic failure is generally thought to result from sub-therapeutic dosing and shortened treatment durations [7]. As a consequence, clinical antimonial drug resistance in Leishmania has yielded the drug useless in various geographical regions. At the same time, the upper limit of dosing of antimonials is limited by severe toxicities, such as pancreatitis and cardiotoxicity [7, 8]. Examples like these emphasize the role of dose optimization and pharmacokinetic (PK) studies for treatments against NTDs, where there is often only a small therapeutic window between treatment failure, engendering drug resistance, and drug toxicity.

Despite the urgent need for new, safer, and more efficacious treatments for NTDs, there is insufficient interest from the pharmaceutical industry to invest in drug development for these diseases because of the limited financial incentive. This paradigm has led to a fatal imbalance in drug development: although NTDs account for 12 % of the global disease burden, only 1 % of all approved drugs during the past decade was developed for these diseases. None of these approved drugs were a new chemical entity, and just 0.5 % of all clinical trials in the past decade were dedicated to NTDs [9].

Owing to the lack of innovation as a result of the absence of financial incentives and the continued use of drugs developed many decades ago, dose-optimization studies or studies in specific patient populations particularly affected by NTDs (e.g., pediatric or HIV co-infected patients) have rarely been reported. While a comprehensive and quantitative overview is currently lacking, only a few clinical trials on NTDs appear to have included studies on the pharmacokinetics of the therapeutic compounds that were under clinical investigation. Rational drug therapy is based on the assumption of a causal relationship between exposure and response. Therefore, characterizing the pharmacokinetics of a drug is of utmost importance. Conventionally, non-compartmental analysis (NCA) methods were used for PK analysis, but these are less powerful and informative for typical NTD PK studies, which are sparse and heterogeneous in nature. NCA has a low power to identify true covariate effects and does not allow for simulations of alternative dosing regimens. Population-based modeling and simulation techniques are therefore more appropriate to describe and predict the relationship between exposure (pharmacokinetics), response (pharmacodynamics), individual patient characteristics, and other covariates of interest (e.g., body weight, sex, and concomitant medication). These pharmacometric methods have become standard in drug development worldwide, and have been recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for PK–pharmacodynamic (PD) data analysis and clinical trial design, particularly in pediatric and small-sized patient populations [10–12]. Nevertheless, these methodologies appear to be systematically underused to address NTDs, likely because their advent occurred much later than the time when many of these drugs were developed.

To better understand to what extent clinical PK studies have contributed to optimization of treatment regimens for NTDs, we performed a systematic review of published clinical PK studies on NTD therapeutics. We hypothesize that for many of the NTD therapeutics, proper PK studies and thus a rationale for their dosing are plainly missing, and that only a few of these studies use modeling and simulation tools. By providing a comprehensive overview of performed PK studies, we illustrate the advantages and drawbacks of different PK methodologies and we identity the gaps in PK research for particular NTDs to indicate the areas where NTD therapeutics can be further improved.

Methods

Study Identification

We performed a systematic literature review following applicable criteria of the most current PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [13], the PRISMA Checklist is in Appendix 1. The MEDLINE database was systematically searched through PubMed for all human clinical PK studies until September 2015 that described the clinical pharmacokinetics of a drug in the treatment of any of the NTDs. For instance, the search term used for studies for Chagas disease was: ((Chagas disease[Title/Abstract] OR American trypanosomiasis[Title/Abstract])) AND (pharmacokinetics[Title/Abstract] OR pharmacokinetic[Title/Abstract]). Reviews were excluded from the search, as well as preclinical research and research concerning animals other than humans. The search was limited to publications in English. A full list of all the search terms used is shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Secondary literature was identified using the bibliographies of the primary identified literature and by specifically querying PubMed using the drug name in combination with the disease. Because we were particularly interested in the application of population PK approaches in NTDs, the abstracts of the Population Approach Group Europe conference [14] were also searched using the same search terms. No specific protocol was developed for this systematic review.

Study Selection

Records were initially screened to identify relevant publications based on title and abstract. If the abstract lacked sufficient detail, the full publication was assessed. The aim of this study was the identification of clinical PK studies in the context of the treatment of NTDs, and therefore studies were excluded if the study’s subjects were not healthy subjects (phase I studies) or patients diagnosed with one of the NTDs; or if the drug of interest was symptomatic treatment (e.g., suppression of fever) or for treatment of concomitant diseases instead of the NTD itself (primary criteria). Articles with only pharmacodynamic results or only reporting a bioanalytical method were also excluded.

Assessment of Pharmacokinetic Data Analysis Methods

The methods used to analyze the PK data were extracted from the identified records and qualitatively categorized as follows, in order of level of complexity: (I) comparison of average trough/steady-state concentrations, (II) NCA, (III) individual-based compartmental analysis, (IV) population-based compartmental analysis, and (V) the use of simulations and/or extrapolations. In category I, studies were included that basically compared a drug concentration at a single time point between different formulations or different patient groups. In category II, we included studies that described concentration-time profiles or PK parameters by using NCA techniques [15]. Analyses in category III used non-linear equations to describe individual concentration-time curves, by using theoretical compartments and inter-compartmental transfer rates, deriving individual PK parameters that can be averaged. In population-based analysis (category IV), similar techniques are being used, but with simultaneous estimation of both inter- and intra-individual variability (nonlinear mixed-effects models). The derived model is descriptive for the entire population and can subsequently be used for predictions and simulations, and potentially for extrapolation to for instance other populations (additional category V).

Extraction and Analysis of Data

Besides the PK data analysis method, other data that were extracted from the identified study reports were: administered compound, measured analytes (parent compound and/or metabolites), route of administration, PK sample matrix, the type and number of subjects, and particularly whether pediatric patients were included in the study. Additionally, the main conclusions were extracted from all studies in a qualitative way, focused on the study recommendations in regard to dose adjustments or other treatment optimizations. The risk of bias in these recommendations, for instance when used analysis methods were insufficient to support these treatment recommendations, was gauged and reported if detected. Given the nature of extracted data, only a simple descriptive analysis was conducted, summarizing individual studies.

Results

Study Characteristics

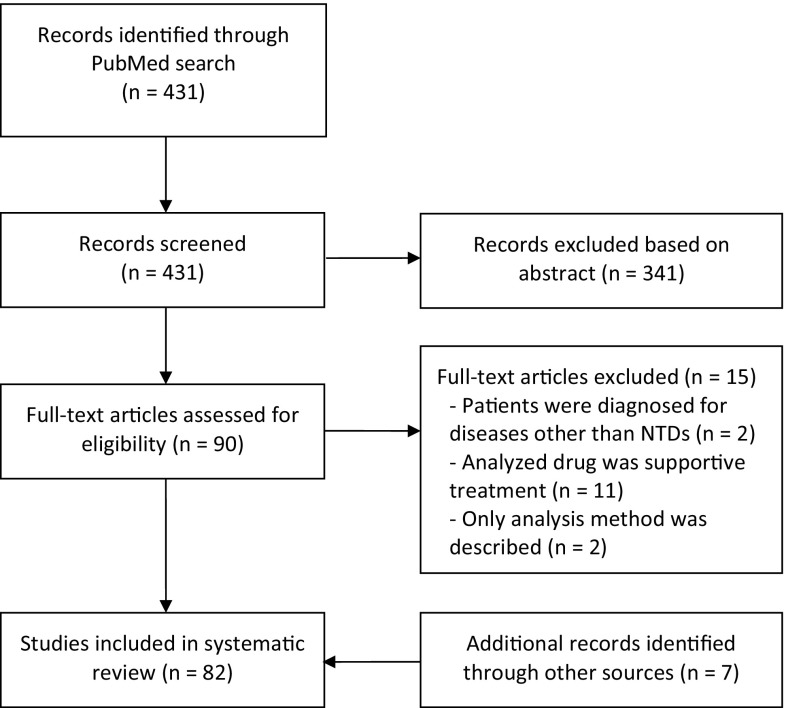

The primary literature search identified 431 unique publications. After screening, 341 publications were excluded based on the primary criteria. Combined with additional articles through secondary sources, 82 publications were eventually included in this systematic review (Fig. 1). No full texts were available for six studies; however, the abstracts of these publications contained all the information to be extracted and they did not need to be excluded. The search and inclusion results stratified per NTD are shown in Supplemental Table 1. A summary of all identified PK studies together with their main characteristics is shown in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram. NTDs neglected tropical diseases

Table 2.

Overview of clinical pharmacokinetic studies in neglected tropical diseases

| Disease | Study | Drug | Administration route | Analytes (parent and metabolites) | Analyzed matrix | Subjects (n) | Pediatrics included | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chagas disease | |||||||||||

| Shapiro et al. [21] | Allopurinol riboside | Oral | Allopurinol (riboside), oxipurinol | Plasma, urine | Male healthy subjects (32) | ||||||

| Were et al. [22] | Allopurinol riboside | Oral | Allopurinol riboside, oxipurinol | Plasma, urine | Male healthy subjects (3) | ||||||

| Garcia-Bournissen et al. [23] | Nifurtimox | Oral | Nifurtimox | Plasma | Healthy subjects (7) | ||||||

| Richle et al. [24] | Benznidazole | Oral | Benznidazole | Plasma | Chagas disease patients (8) | ||||||

| Altcheh et al. [25] | Benznidazole | Oral | Benznidazole | Plasma | Chagas disease patients (40) | ✓ | |||||

| Soy et al. [26] | Benznidazole | Oral | Benznidazole | Plasma | Chagas disease patients (39) | ||||||

| Human African trypanosomiasis | |||||||||||

| Bronner et al. [28] | Pentamidine | IM | Pentamidine | Plasma, whole blood, CSF | T. b. gambiense trypanosomiasis patients (11) | ||||||

| Bronner et al. [29] | Pentamidine | IV | Pentamidine | Plasma | T. b. gambiense trypanosomiasis patients (11) | ||||||

| Harrison et al. [30] | Melarsoprol | IV | Arsenic | Urine | T. b. rhodesiense trypanosomiasis patients (28) | ||||||

| Burri et al. [31] | Melarsoprol | IV | Melarsoprol | Serum, CSF | T. b. gambiense trypanosomiasis patients (19) | ||||||

| Burri et al. [32] | Melarsoprol | IV | Melarsoprol | Serum, CSF | T. b. gambiense trypanosomiasis patients (22) | ||||||

| Bronner et al. [33] | Melarsoprol | IV | Melarsoprol | Plasma, urine, CSF | T. b. gambiense trypanosomiasis patients (8) | ||||||

| Milord et al. [34] | Eflornithine | IV | Eflornithine | Serum, CSF | T. b. gambiense trypanosomiasis patients (63) | ✓ | |||||

| Na-Bangchang et al. [35] | Eflornithine | Oral | Eflornithine | Plasma, CSF | T. b. gambiense trypanosomiasis patients (25) | ||||||

| Jansson-Lofmark et al. [36] | Eflornithine | Oral | Eflornithine | Plasma, CSF | T. b. gambiense trypanosomiasis patients (25) | ||||||

| Tarral et al. [37], Gualano et al. [38] | Fexinidazole | Oral | Fexinidazole sulfoxide, fexinidazole sulfone | Plasma, urine | Male healthy subjects (154) | ||||||

| Leishmaniasis | |||||||||||

| Al Jaser et al. [44] | Sodium stibogluconate | IM | Antimony | Blood, urine | CL patients (29) | ||||||

| Al Jaser et al. [52] | Sodium stibogluconate | IM | Antimony | Blood, skin biopsies | CL patients (9) | ||||||

| Reymond et al. [47] | Sodium stibogluconate | IV | Antimony | Serum | Patient with AIDS and VL (1) | ||||||

| Vasquez et al. [45] | Pentavalent antimony | IM | Pentavalent and trivalent antimony | Blood, urine | Healthy subjects (5) | ||||||

| Chulay et al. [48] | Sodium stibogluconate, meglumine antimoniate | IM | Antimony | Blood | VL patients (5) | ||||||

| Cruz et al. [53] | Meglumine antimoniate | IM | Antimony | Plasma, urine | CL patient (24) | ✓ | |||||

| Zaghloul et al. [46] | Sodium stibogluconate | IM | Antimony | Plasma, urine | CL patient (12) | ||||||

| Shapiro et al. [21] | Allopurinol riboside | Oral | Allopurinol, riboside, oxipurinol | Plasma, urine | Male healthy subjects (32) | ||||||

| Were and Shapiro [22] | Allopurinol riboside | Oral | Allopurinol riboside, oxipurinol | Plasma, urine | Male healthy subjects (3) | ||||||

| Musa et al. [49] | Paromomycin sulphate | IM | Paromomycin | Plasma, urine | VL patients (9) | ✓ | |||||

| Ravis et al. [50] | Paramomycin, WR 279396 | Topical | Paromomycin | Plasma | CL patients (60) | ✓ | |||||

| Sundar et al. [51] | Sitamaquine | Oral | Sitamaquine, desethyl-sitamaquine | Plasma | VL patients (41) | ||||||

| Dorlo et al. [40] | Miltefosine | Oral | Miltefosine | Plasma | Old world CL patients (31) | ||||||

| Dorlo et al. [41] | Miltefosine | Oral | Miltefosine | Plasma | VL patients (96) | ✓ | |||||

| Dorlo et al. [42] | Miltefosine | Oral | Miltefosine | Plasma | Simulated female VL patients | ||||||

| Dorlo et al. [43] | Miltefosine | Oral | Miltefosine | Plasma | VL patients (81) | ✓ | |||||

| Buruli ulcer | |||||||||||

| Alffenaar et al. [55] | Streptomycin-rifampicin, rifampin-clarithromycin | Oral | Rifampicin, 25-desacetylrifampicin, clarithromycin, 14OH-clarithromycin | Plasma | Buruli ulcer patients (13) | ✓ | |||||

| Leprosy | |||||||||||

| Mehta et al. [63] | Rifampicin | Oral | Rifampicin | Serum | MB (6) and PB (12) leprosy patients | ||||||

| Venkatesan et al. [61] | Rifampicin and dapsone | Oral | Rifampicin and dapsone | Plasma, urine | Leprosy patients (15) | ||||||

| Pieters and Zuidema [56] | Monoacetyldapsone | IA | Dapsone | Serum | Healthy subjects (22) | ||||||

| Pieters and Zuidema [57] | Dapsone | Oral | Dapsone | Serum | Healthy subjects (5) | ||||||

| Garg et al. [58] | Dapsone | Oral | Dapsone, monoacetyldapsone | Plasma | Lepromatous leprosy patients (15) | ||||||

| Venkatesan et al. [62] | Dapsomine | Oral | Dapsone | Plasma | Lepromatous leprosy patients(14) | ||||||

| Pieters et al. [64] | Dapsone | Oral | Dapsone | Plasma | Leprosy patients (23) | ||||||

| Moura et al. [59] | Dapsone | Oral | Dapsone | Plasma | MB leprosy patients (33) | ||||||

| Nix et al. [60] | Clofazamine | Oral | Clofazamine | Plasma | Healthy subjects (16) | ||||||

| Teo et al. [66] | Thalidomide | Oral | Thalidomide | Plasma | Healthy subjects (17) | ||||||

| Teo et al. [65] | Thalidomide | Oral | Thalidomide | Plasma | Healthy subjects (15) | ||||||

| Trachoma | |||||||||||

| Amsden et al. [67] | Azithromycin, albendazole, ivermectin | Oral | Azithromycin, albendazole sulfoxide, ivermectin H2B1a and H2B1b | Plasma | Healthy subjects (18) | ||||||

| El-Tahtawy et al. [68] | Ivermectin | Oral | Ivermectin H2B1a and H2B1b | Plasma | Healthy subjects (15) | ||||||

| Cysticercosis/taeniasis | |||||||||||

| Jung et al. [75] | Albendazole | Oral | Albendazole sulfoxide | Plasma | Brain cysticercosis patients (8) | ||||||

| Sanchez et al. [70] | Albendazole | Oral | Albendazole sulfoxide | Plasma, urine | Parenchymal brain cysticercosis patients (10) | ||||||

| Jung et al. [69] | Albendazole | Oral | Albendazole sulfoxide | Plasma | Brain cysticercosis patients (8) | ✓ | |||||

| Takayanagui et al. [71] | Albendazole | Oral | Albendazole sulfoxide | Plasma | Parenchymal brain cysticercosis patients (24) | ||||||

| Na-Bangchang et al. [72] | Praziquantel | Oral | Praziquantel | Plasma | Neurocysticercosis patients (11) | ||||||

| Jung et al. [73] | Praziquantel | Oral | Praziquantel | Plasma | Healthy subjects (8) | ||||||

| Garcia et al. [74] | Praziquantel, albendazole | Oral | Praziquantel, albendazole sulfoxide | Plasma | Neurocysticercosis patients (32) | ||||||

| Echinococcosis | |||||||||||

| Cotting et al. [76] | Albendazole | Oral | Albendazole sulfoxide | Plasma | Echinococcosis patients (19) | ||||||

| Mingjie et al. [77] | Albendazole | Oral | Albendazole sulfoxide | Serum | Male cystic echinococcosis patients (7) | ||||||

| Schipper et al. [78] | Albendazole | Oral | Albendazole sulfoxide | Plasma | Male healthy subjects (6) | ||||||

| Food-borne trematodiases | |||||||||||

| Na Bangchang et al. [79] | Praziquantel | Oral | Praziquantel | ? | Opisthorchiasis patients (18) | ||||||

| Choi et al. [80] | Praziquantel | Oral | Praziquantel | Plasma | Healthy subjects (12) and clonorchiasis patients (20) | ||||||

| Lecaillon et al. [81] | Triclabendazole | Oral | Triclabendazole, sulfoxide, sulfone | Plasma | Fascioliasis patients (20) | ||||||

| El-Tantawy et al. [82] | Triclabendazole | Oral | Triclabendazole sulfoxide | Plasma | Healthy subjects (12) and fascioliasis patients (12) | ||||||

| Lymphatic filariasis | |||||||||||

| Shenoy et al. [83] | Diethylcarbamazine, albendazole | Oral | Diethylcarbamazine, albendazole sulfoxide | Plasma | Healthy subjects (42) | ||||||

| Sarin et al. [84] | Albendazole sulfoxide | Oral | Albendazole sulfoxide, albendazole sulfone | Plasma | Healthy subjects (10) | ||||||

| Abdel-tawab et al. [85] | Albendazole | Oral | Albendazole, sulfoxide, albendazole sulfone | Serum, breast milk | Lactating women (33) | ||||||

| Onchocerciasis | |||||||||||

| Lecaillon et al. [93] | Amocarzine | Oral | Amocarzine, N-oxide metabolite | Plasma, urine | Onchocerciasis patients (41) | ||||||

| Lecaillon et al. [94] | Amocarzine | Oral | Amocarzine, N-oxide metabolite | Plasma, urine | Male onchocerciasis patients (20) | ||||||

| Awadzi et al. [86] | Albendazole | Oral | Albendazole sulfoxide | Plasma | Onchocerciasis patients (36) | ||||||

| Awadzi et al. [87] | Ivermectin, albendazole | Oral | Ivermectin, albendazole sulfoxide | Plasma | Male onchocerciasis patients (42) | ||||||

| Okonkwo et al. [88] | Ivermectin | Oral | Ivermectin | Plasma, urine, saliva | Onchocerciasis patients (9) | ||||||

| Baraka et al. [89] | Ivermectin | Oral | Ivermectin | Plasma, tissues | Onchocerciasis patients (25), healthy subjects (14) | ||||||

| Homeida et al. [90] | Ivermectin | Oral | Ivermectin | Plasma | Male subjects (10) | ||||||

| Chijioke et al. [91] | Suramin | IV | Suramin | Plasma | Male onchocerciasis patients (10) | ||||||

| Korth-Bradley et al. [92] | Moxidectin | Oral | Moxidectin | Plasma, breast milk | Healthy lactating women (12) | ||||||

| Schistosomiasis | |||||||||||

| Nordgren et al. [98] | Metrifonate | Oral | Metrifonate, dichlorvos | Plasma | Male schistosomiasis patients (2) | ||||||

| Daneshmend and Homeida [99] | Oxamniquine | Oral | Oxamniquine | Plasma | Hepatosplenic schistosomiasis patients (9), healthy subjects (5) | ||||||

| Pehrson et al. [95] | Praziquantel | Oral | Praziquantel | Serum, urine, dialysis fluid | Patient with uremia (1) | ||||||

| Mandour et al. [96] | Praziquantel | Oral | Praziquantel | Serum or plasma | Healthy subjects (20), schistosomiasis patients (9) | ||||||

| Valencia et al. [97] | Praziquantel | Oral | Praziquantel | Serum | Schistosoma japonicum patients (4) | ||||||

| El Guiniady et al. [16] | Praziquantel | Oral | Praziquantel | Serum | Schistosoma mansoni patients (40) | ||||||

| Rabies | |||||||||||

| Merigan et al. [100] | Human leukocyte interferon | I-VENTRIC, IT, IM | Human leukocyte interferon | Serum, CSF | Suspected rabies patients (2), symptomatic rabies patients (5) | ||||||

| Lang et al. [17] | Equine rabies immunoglobulin | IM | Anti-rabies antibodies | Serum | Healthy subjects (27) | ||||||

| Gogtay et al. [18] | IgG1 monoclonal antibody | IM | Anti-rabies antibodies | Serum | Male healthy subjects (29) | ||||||

| Disease | Study | Analysis method | Aim of the study | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparing concentrations (1) | Noncompartmental (2) | Compartmental (individual-based) (3) | Compartmental (population-based) (4) | Simulation and/or extrapolation (5) | Descriptive | Suggesting alternative dose regimens | Comparing different formulations | Evaluating drug–drug and food interactions | Evaluating exposure-response relationships | ||

| Chagas disease | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Shapiro et al. [21] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Were et al. [22] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Garcia-Bournissen et al. [23] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Richle et al. [24] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Altcheh et al. [25] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Soy et al. [26] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Human African trypanosomiasis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Bronner et al. [28] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Bronner et al. [29] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Harrison et al. [30] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Burri et al. [31] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Burri et al. [32] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Bronner et al. [33] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Milord et al. [34] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Na-Bangchang et al. [35] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Jansson-Lofmark et al. [36] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Tarral et al. [37], Gualano et al. [38] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Leishmaniasis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Al Jaser et al. [44] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Al Jaser et al. [52] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Reymond et al. [47] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Vasquez et al. [45] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Chulay et al. [48] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cruz et al. [53] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Zaghloul et al. [46] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Shapiro et al. [21] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Were and Shapiro [22] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Musa et al. [49] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Ravis et al. [50] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Sundar et al. [51] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dorlo et al. [40] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dorlo et al. [41] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Dorlo et al. [42] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Dorlo et al. [43] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Buruli ulcer | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Alffenaar et al. [55] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Leprosy | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Mehta et al. [63] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Venkatesan et al. [61] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pieters and Zuidema [56] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Pieters and Zuidema [57] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Garg et al. [58] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Venkatesan et al. [62] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pieters et al. [64] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Moura et al. [59] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Nix et al. [60] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Teo et al. [66] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Teo et al. [65] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Trachoma | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Amsden et al. [67] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| El-Tahtawy et al. [68] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Cysticercosis/taeniasis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Jung et al. [75] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Sanchez et al. [70] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Jung et al. [69] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Takayanagui et al. [71] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Na-Bangchang et al. [72] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Jung et al. [73] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Garcia et al. [74] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Echinococcosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Cotting et al. [76] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Mingjie et al. [77] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Schipper et al. [78] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Food-borne trematodiases | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Na Bangchang et al. [79] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Choi et al. [80] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Lecaillon et al. [81] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| El-Tantawy et al. [82] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Lymphatic filariasis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Shenoy et al. [83] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Sarin et al. [84] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Abdel-tawab et al. [85] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Onchocerciasis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Lecaillon et al. [93] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Lecaillon et al. [94] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Awadzi et al. [86] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Awadzi et al. [87] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Okonkwo et al. [88] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Baraka et al. [89] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Homeida et al. [90] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Chijioke et al. [91] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Korth-Bradley et al. [92] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Schistosomiasis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Nordgren et al. [98] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Daneshmend and Homeida [99] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pehrson et al. [95] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Mandour et al. [96] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Valencia et al. [97] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| El Guiniady et al. [16] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Rabies | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | a | b | c | d | e | |

| Merigan et al. [100] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Lang et al. [17] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Gogtay et al. [18] | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

AIDS acquired immune deficiency syndrome, CL cutaneous leishmaniasis, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, IgG1 immunoglobulin G1, IA intra-adipose, IM intramuscular, IT intrathecal, IV intravenous, I-VENTRIC intraventricular, MB multibacillary, PL paucibacillary, VL visceral leishmaniasis, ? unknown

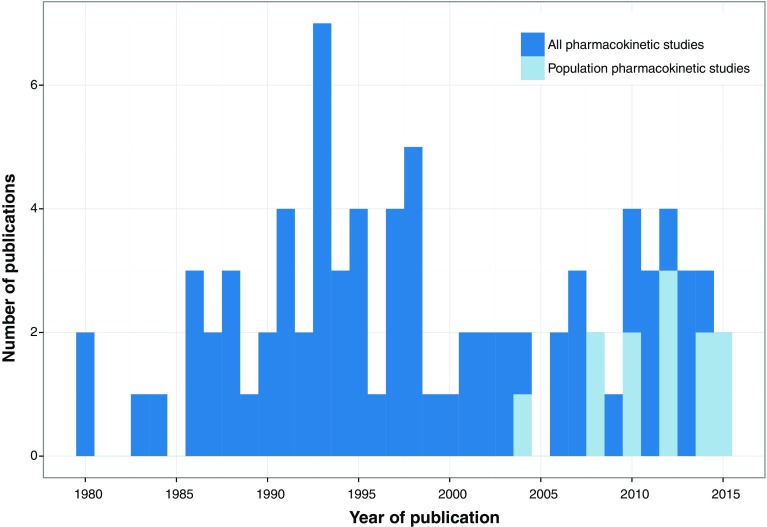

For four out of the 17 (24 %) NTDs, not a single PK study could be identified, these were yaws, dracunculiasis, dengue/chikungunya/zika and soil-transmitted helminthiases. For six (41 %) other NTDs, fewer than five PK studies had been reported. Most studies had included small patient numbers, only five studies (6.1 %) had included >50 subjects (Table 2). Pediatric patients were included in nine (11 %) studies. The majority of these studies were not very recent; 56 % of studies were published before 2000; the frequency of studies per year is depicted in Fig. 2. Concerning the used analysis methods, some studies employed multiple analysis methods, e.g., both comparison of steady-state concentrations and NCA (Table 2). When looking at the most complicated method employed in the study, most studies used NCA methods for PK analysis (62 %). Twelve studies (15 %) used population-based compartmental analysis, of which eight (10 %) additionally performed simulations or extrapolation. Regarding the aim of the studies, 38 studies (46 %) focused on describing the pharmacokinetics of a compound without further interpretations. Only five studies (6 %) evaluated exposure-response relationships. Although some of these studies reported side effects [16–18], none of these attempted to relate drug exposure to observed toxicity. However, relatively many studies (28 %) evaluated drug–drug and food interactions. This is owing to the frequent use of combination therapies for the treatment of NTDs, and the implementation of overlapping prophylactic mass drug administrations, e.g., onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis, and schistosomiasis.

Fig. 2.

Number of identified clinical pharmacokinetic publications on neglected tropical diseases stratified per year

Pharmacokinetic Studies per Neglected Tropical Disease

Based on the cause of the infection, NTDs can be divided into four groups: diseases caused by protozoal parasites, bacteria, helminthes, and viruses (an extensive overview is provided in Table 1). The protozoal NTDs are all caused by kinetoplastid parasites: Chagas disease, human African trypanosomiasis, and leishmaniasis. Bacteria, a large and diverse group of prokaryotic microorganisms, cause Buruli ulcer, leprosy (both caused by Mycobacteria), trachoma, and yaws. Helminthes, commonly known as parasitic worms, are large multicellular organisms. The helminth NTDs are cysticercosis/taeniasis, dracunculiasis, echinococcosis, food-borne trematodiases, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis, and the soil-transmitted helminthiases. Viral NTDs include the arboviral disease dengue (plus chikungunya and zika) and rabies. A general overview of medicines that are currently in use for NTDs is listed in Table 3 [1, 19].

Table 3.

Currently used drugs for neglected tropical diseases

| Disease | Drug | Route of administration |

|---|---|---|

| Chagas disease | ||

| Benznidazole | Oral | |

| Nifurtimox | Oral | |

| Human African trypanosomiasis | ||

| Early stage | Pentamidine | IV, IM |

| Suramin | IV | |

| Late stage | Melarsoprol | IV |

| Nifurtimox and eflornithine | IV and IV | |

| Leishmaniasis | ||

| Meglumine antimoniate | IL, IV, IM | |

| Sodium stibogluconate | IL, IV, IM | |

| Paromomycin (paromomycin ointment or WR 279396 cream) | Topical, IM | |

| Pentamidine | IV, IM | |

| Amphotericin B deoxycholate | IV | |

| Liposomal amphotericin B | IV | |

| Fluconazole | Oral | |

| Ketoconazole | Oral | |

| Miltefosine | Oral | |

| Buruli ulcer | ||

| Rifampicin and streptomycin | Oral and IM | |

| Alternative compounds: | ||

| Clarithromycin | Oral | |

| Moxifloxacin | Oral | |

| Leprosy | ||

| Multibacillary | Rifampicin and dapsone | Oral and oral |

| Paucibacillary | Rifampicin, dapsone, and clofazimine | Oral, oral, and oral |

| Trachoma | ||

| Azithromycin | Oral | |

| Tetracycline | Topical | |

| Endemic treponematoses | ||

| Azithromycin | Oral | |

| Penicillin G benzathine | IM | |

| Cysticercosis/taeniasis | ||

| Albendazole | Oral | |

| Praziquantel | Oral | |

| Dracunculiasisa | ||

| Echinococcosis | ||

| Albendazole | Oral | |

| Food-borne trematodiases | ||

| Clonorchiasis and opisthorchiasis | Praziquantel | Oral |

| Fascioliasis | Triclabendazole | Oral |

| Paragonimiasis | Praziqantel or triclabendazole | Oral and oral |

| Lymphatic filariasis | ||

| Diethylcarbamazine | Oral | |

| Additional treatment: | ||

| Doxycycline | Oral | |

| Ivermectin | Oral | |

| Albendazole | Oral | |

| Onchocerciasis | ||

| Microfilaricidal therapy: | ||

| Ivermectin | Oral | |

| Macrofilaricidal therapy: | ||

| Doxycycline followed by ivermectin | Oral and oral | |

| Schistosomiasis | ||

| Praziquantel | Oral | |

| Soil-transmitted helminthiases | ||

| Albendazole | Oral | |

| Mebendazole | Oral | |

| Pyrantel pamoate | Oral | |

| Dengue and chikungunyab | ||

| Rabiesc | ||

IL intralesional, IM intramuscular, IV intravenous

aFor dracunculiasis, treatment involves removing the adult worm

bTreatment of dengue and chikungunya consists of relieving symptoms

cAfter exposure by an animal that might have rabies, post-exposure anti-rabies vaccination is recommended to prevent rabies infection

We discuss the most salient identified PK studies for NTD therapies, focusing on studies that played a role in treatment optimization. A full overview of identified studies can be found in Table 2.

Chagas Disease

Around 5.7 million people worldwide are affected by Chagas disease (also known as American trypanosomiasis), which is caused by the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite [20]. The acute phase of the disease is asymptomatic in most patients. During the chronic phase, patients can experience cardiac, digestive, or neurological symptoms, which complications lead in many patients to fatality in the late chronic stage mostly decades after the start of infection. However, Chagas disease can be cured when treatment is initiated at the acute or early chronic stage. Currently, the only two drugs with proven efficacy in Chagas disease are nifurtumox and benznidazole (Table 3). Clinical PK studies were found for three drugs: allopurinol riboside [21, 22], nifurtimox [23], and benznidazole [24–26] (Table 2).

Allopurinol was not further evaluated for the treatment of Chagas disease after demonstrating suboptimal exposure [21], which could not be sufficiently increased by probenecid co-administration decreasing the drug’s renal excretion [22]. A population PK modeling and simulation approach was used to estimate the exposure of infants to nifurtimox via breastmilk of patients [23]. Transfer of nifurtimox into breastmilk appeared limited and unlikely to lead to significant exposure in infants, yielding nifurtimox safe to use for breastfeeding patients. The first PK study on benznidazole was published in 1980 [24]. Very recently, population-based analyses were performed in children [25] and in adults [26]. Model-based simulations in these studies suggested that the adult daily dose intervals in chronic Chagas patients could be prolonged, while benznidazole concentrations were kept within the target range, potentially simplifying the treatment regimen.

Human African Trypanosomiasis

Human African trypanosomiasis, also known as sleeping sickness, is transmitted by the tsetse fly and caused by T. b. rhodesiense, resulting in an acute infection, and T. b. gambiense, leading to a more chronic infection (Table 1). Without treatment, the infection of the central nervous system is ultimately fatal [27]. There are currently four treatments in use for the two different stages of human African trypanosomiasis (Table 3), all of which exhibit substantial toxicities: pentamidine, suramin, melarsoprol, and nifurtimox plus eflornithine. Clinical PK studies were identified for three of these treatments: pentamidine [28, 29], melarsoprol [30–33], and eflornithine [34–36]. Additionally, PK studies were found for fexinidazole, a drug currently still in late-phase clinical development [37, 38].

Pharmacokinetics played an important role in the optimization of eflornithine therapy. Based on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma PK data from late-stage T. b. gambiense trypanosomiasis, a new dosing regimen was proposed for eflornithine, including different infusion intervals, and increased doses in children, based on body surface area instead of body weight [34]. Later, it was shown that the current dosing of oral eflornithine did not result in adequate therapeutic plasma and CSF concentrations in adult patients [35]. Recently, a population-based PK–PD model for the different stereoisomers of eflornithine was developed reanalyzing previous PK data and showed the importance of stereoselective exposure, which provided an explanation why oral eflornithine had failed so far for late-stage human African trypanosomiasis patients [36].

Melarsoprol pharmacokinetics in plasma and CSF was assessed using compartmental methods in 19 trypanosomiasis patients, after which the typical exposure for safer alternative dose regimens could be simulated [31]. However the PK–PD relationships for melarsoprol remain unclear: melarsoprol PK parameters and CSF/plasma exposure were not significantly different in refractory compared with cured patients [32] and arsenic urinary excretion was not predictive of either toxicity or efficacy of melarsoprol [30].

Fexinidazole, a nitroimidazole-compound currently in clinical development for human African trypanosomiasis, and its active metabolites were studied in healthy volunteers. The study showed the need for concomitant food intake, which increases the bioavailability of this compound substantially, and identified a target dose for the first in-patient studies [37, 38].

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is caused by various species of Leishmania parasites that are transmitted by sandflies, with different and widespread geographical regions of distribution, leading to distinctly different clinical presentations. Cutaneous leishmaniasis is most prevalent and has the potential to progress into mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Visceral leishmaniasis is the most severe clinical form and is inevitably fatal if left untreated. Treatment of leishmaniasis depends on the type of disease, parasite species, and on the availability of treatment depending on the geographical location. Local chemotherapeutic treatment with intralesional pentavalent antimonials or paromomycin cream can be an option for cutaneous leishmaniasis, although some species or severe/diffuse disease are rather treated systemically with either parenteral antimonials, liposomal amphotericin B, pentamidine or oral miltefosine, ketoconazole, and fluconazole [39]. Recommended treatments for VL are, depending on species and geographical location, either parenteral (liposomal) amphotericin B, the antimonial sodium stibogluconate, paromomycin, oral miltefosine, or combinations of sodium stibogluconate with paromomycin (East Africa) or liposomal amphotericin B plus paromomycin/miltefosine (India). Several clinical PK studies were conducted in leishmaniasis, and have helped most notably to optimize dose regimens for miltefosine for VL [40–43], for antimonials for cutaneous leishmaniasis [44–46] and for VL [47, 48], to quantify exposure to paromomycin in VL [49], and to assess systemic penetration of topical paromomycin formulations [50]. Few studies have been performed in the context of leishmaniasis on allopurinol [21, 22] and sitamaquine [51] of which both are not in clinical use at the moment.

Comparing the two pentavalent antimonial compounds in use for leishmaniasis, meglumine antimoniate, and sodium stibogluconate, equivalent systemic exposure was shown for the active component pentavalent antimony, possibly indicating that they can be used interchangeably [48]. In cutaneous leishmaniasis, PK studies on parenteral sodium stibogluconate demonstrated wide variability in drug exposure [44], but also penetration of the active component antimony in the skin, with no differences between normal skin and lesions [52]. The first pediatric study of meglumine antimoniate showed that drug exposure is significantly lower in children than in adults treated with the same linear weight-adjusted (mg/kg) regimen, possibly indicating that children are currently undertreated [53]. Only a descriptive analysis of the pharmacokinetics was performed, which did not suggest or evaluate alternative dose regimens for children.

Systemic penetration of paromomycin and gentamycin after application of two different topical formulations in cutaneous leishmaniasis patients was assessed using compartmental methods [50]. While gentamycin remained largely undetectable in plasma, paromomycin accumulated to 5–9 % of typical trough concentrations achieved after a standard intramuscular administration of 15 mg/kg paromomycin, indicating little concern for systemic drug toxicity of the topical formulations.

Most PK studies in leishmaniasis were conducted on the oral drug miltefosine. In 2008, the first population PK model for this drug was developed on data from Dutch military personnel who contracted L. major cutaneous leishmaniasis in Afghanistan [40]. This analysis showed that miltefosine is eliminated at a much slower rate than expected, which has potential implications for emerging drug resistance and the required contraception period owing to the teratogenicity of miltefosine. A subsequent simulation study focused on the translation of the reproductive safety limit in animal studies to Indian female VL patients. New recommendations for the duration of contraceptive cover after miltefosine treatment were provided based on these findings [41]. In a model-based study, miltefosine exposure appeared to be lower in children than in adults treated with the same mg/kg dose, possibly explaining increased failure rates observed in pediatric VL patients. A new dosing algorithm based on allometric scaling was proposed and was evaluated by Monte Carlo simulations [42]. Recently, a PK–PD model of miltefosine in Nepalese VL patients indeed identified a PK–PD relationship between miltefosine exposure and long-term treatment relapse [43]. The confirmed underexposure in children, reinforces the need for implementing the earlier proposed allometric miltefosine dosing regimen for VL [42, 43].

Buruli Ulcer

Buruli ulcer is an ulcerating infection caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans, leading to long-term functional disability, loss of productivity, and stigmatization. Antimicrobial treatment is particularly effective in small lesions and at an early stage of infection, it reduces healing time, recurrence rate, and the need for surgical intervention [54]. Different combinations of antimicrobials are used, depending on available resources and the stage of the disease. The most widely accepted combination is oral rifampicin with intramuscular streptomycin, the oral combination of rifampicin with clarithromycin is still under clinical evaluation. Only a single PK study could be identified for Buruli ulcer, which studied systemic pharmacokinetics of rifampicin and clarithromycin in patients using population compartmental methods [55].

In this study, the counteracting interaction effects (both cytochrome P450 3A4 and P-glycoprotein) of clarithromycin and rifampicin on each other’s pharmacokinetics were investigated. Eventually, it was suggested that a doubled dose of clarithromycin should be evaluated in future clinical studies to ensure an increased time above the minimum inhibitory concentration [55].

Leprosy

Leprosy can be divided into paucibacillary and multibacillary disease. If not treated in an early phase, it results in lifelong neuropathy and disability. A combination of drugs is needed because of the emergence of drug resistance. In 1995, the WHO supplied free multi-drug therapy to leprosy patients in all endemic countries, which led to a dramatic decrease in prevalence. For paucibacillary treatment, the recommended all oral treatment combination is rifampicin plus dapsone, for multibacillary treatment; this combination should be extended with clofazimine (Table 3). Various PK studies have been conducted on dapsone [56–59], clofazimine [60], and specific drug–drug interaction studies focusing on the interactions between dapsone, clofazimine, and rifampicine using various formulations [61–64]. A few studies focused on thalidomide pharmacokinetics [65, 66], which is currently largely considered obsolete because of its teratogenicity. PK studies for leprosy were mainly performed in the 1980/90s and generally using NCA methods (Table 2).

A study on dapsone and its main active metabolite monoacetyldapsone in leprosy patients concluded that the standard 100-mg/day dose was sufficient to maintain therapeutic plasma concentrations in relation to in vitro susceptibility values [58]. Nevertheless, dose adjustments might be needed for obese patients treated with this regimen [59]. Various drug–drug interaction studies did not reveal clinical significant interactions, although little is known about the required minimal effective exposure in leprosy [61–64].

Pharmacokinetics of clofazimine has been analyzed using compartmental methods after various fed and fasting conditions to determine food effects and the relative bioavailability [60]. A high-fat meal increased bioavailability significantly and was therefore considered preferable, although exposure–effect relationships for clofazimine in leprosy have not been properly established.

Trachoma

Trachoma is the leading infectious cause of blindness worldwide. The infection of the eye by Chlamydia trachomatis can be divided into two clinical stages: initial active trachoma (inflammation) and cicatricial disease (eyelid scarring). Active trachoma is mostly seen in young children and cicatricial disease and eventual blindness are typically seen in adults. Treatment and prevention of trachoma consists of surgery and mass drug administration of antibiotic treatment. The WHO recommends either single-dose oral azithromycin or topical tetracycline. Because trachoma commonly geographically overlaps with other NTDs such as onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis, regional elimination initiatives for these diseases in terms of mass drug administrations are often aimed to be combined. Pharmacokinetic studies have therefore focused on drug–drug interactions between azithromycin and drugs used in mass drug administration for these other NTDs (ivermectin and albendazole) [67, 68].

Ivermectin exposure appeared to be increased in healthy volunteers in combination with azithromycin and the authors recommended subsequent modeling and simulation to predict and evaluate an optimal dosing regimen for this drug combination [67]. A subsequent population PK analysis of the same data showed the benefit of modeling and simulation by pinpointing that the mechanism of this interaction was an increase in bioavailability and demonstrating that maximum expected ivermectin exposures after concomitant administration of azithromycin were still within a well-tolerated range, meaning that combining these drugs in mass drug administrations should be feasible [68].

Endemic Treponematoses

Endemic treponematoses are a group of chronic bacterial infections, related to venereal syphilis, caused by treponemes that mainly affect the bones and/or skin causing localized lesions. The spectrum of diseases includes yaws, endemic syphilis (bejel), and pinta. Yaws is the most prevalent form of non-venereal treponematosis, and while rarely fatal, it can lead to chronic disfigurement and disability. Treatment consists of a single dose of long-acting penicillin or oral azithromycin. No PK studies could be identified for drugs used to treat endemic treponematoses.

Cysticercosis/Taeniasis

Cysticercosis and taeniasis are both caused by species of the Taenia tapeworm. Taeniasis is the intestinal infection with adult tapeworms. This mild disease is an important cause for transmission of cysticercosis, an infection with the larval stage of the pork tapeworm Taenia solium that can cause life-threatening clinical manifestations. The most severe form is neurocysticercosis in which the larval cysts are located in the central nervous system and cause severe neurological symptoms. The treatment of (neuro-)cysticercosis is not fully established. Besides symptomatic treatment (antiepileptics), it remains debated whether, and if so in which cases, antiparasitic and concomitant anti-inflammatory treatment to reduce inflammation associated with the dying organism are indicated. The main antiparasitic agents used in cysticercosis are albendazole and praziquantel, while the supportive anti-inflammatory therapy can be corticosteroids or methotrexate. Pharmacokinetic studies are available for both albendazole [69–71, 75] and praziquantel [72–74], and have focused on drug–drug interactions [71–74].

Albendazole sulfoxide, the main metabolite of albendazole, has been studied in several clinical trials on neurocysticercosis. Despite the absence of an established PK–PD relationship, these studies suggested based on the area under the concentration-time curve and steady-state trough concentrations that albendazole administration could be changed from the current clinical practice of three times daily, to twice daily [70, 75]. Conversely, a small descriptive study in children advised an opposite dose adjustment, given the increased clearance in children [69]. Drug–drug interaction studies indicated that there were no interactions with antiepileptic drugs and that dexamethasone even decreased the elimination rate of albendazole [71]. Co-administration of the antiparasitic praziquantel increased albendazole sulfoxide exposure possibly synergizing the efficacy of both drugs when administered together [74].

Drug–drug interaction studies with praziquantel demonstrated that exposure was decreased in combination with dexamethasone and anti-epileptic drugs possibly related to induction of cytochrome P450-mediated hepatic metabolism [72]. Conversely, co-administration of the histamine H2-receptor antagonist cimetidine was demonstrated to prolong exposure of praziquantel, suggesting the possibility for further improvement of efficacy of this single-day therapy [73].

Dracunculiasis

Dracunculiasis is also known as guinea-worm disease. The infection is transmitted by drinking unfiltered water containing the larvae of Dracunculus medinensis. Treatment consists of slow extraction of the worm combined with wound care and pain management. There is no specific chemotherapy indicated to treat dracunculiasis and no PK studies were found.

Echinococcosis

There are four species of Echinococcus tapeworms that can cause infection in humans. Humans are an incidental host; with transmission through for example, contaminated environmental water. The two main types of disease are cystic echinococcosis and alveolar echinococcosis, both characterized by the slow growth of cyst-like larvae, usually in the liver. Development of active disease can take multiple years. Oral albendazole is the chemotherapy of choice for both disease types, sometimes combined with surgery or percutaneous drainage of the cysts. Albendazole is poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and most PK studies have focused on improving the bioavailability of the compound [76–78].

The pharmacokinetics of albendazole and its main metabolite, albendazole sulfoxide, have been studied in patients with echinococcosis [76]. It was shown that extrahepatic cholestasis, a common symptom of echinococcosis, delayed the absorption and decreased the elimination rate of albendazole. Another study looked at bioequivalence between a novel emulsified formulation of albendazole compared with a standard oral tablet formulation [77]. To improve the low bioavailability of albendazole, co-administration with cimetidine was studied [78]. The high inter-individual variability in drug exposure and the various possible contradictory effects of cimetidine on both absorption (increased) by decreasing the gastrointestinal pH and metabolism by cytochrome P450 enzyme inhibition for both albendazole and its sulfoxide metabolite complicated the descriptive interpretation of the results from this study [78].

Food-Borne Trematodiases

Food-borne trematodiases are zoonotic infections caused by parasitic flatworms, so-called ‘liver flukes’, which can result in clonorchiasis, opisthorchiasis, fascioliasis, and paragonimiasis. Transmission cycles differ widely, but generally involve ingestion of food contaminated with the parasite larvae. The worms are mainly located in the liver and gall bladder or in the lung (paragonimiasis). Different anti-helminthic compounds are used, depending on the infecting worm (Table 3), but praziquantel and triclabendazole are two of the main drugs in use for this group of diseases. Pharmacokinetic studies were found for both these drugs [79–82], although no studies were found in the context of paragonimiasis (lung fluke). Given the liver damage caused by the flukes, many PK studies focused on a disease effect on cytochrome P450 enzyme-mediated metabolism of the compounds, which appeared most prominent for the cytochrome P450 3A4 substrate praziquantel [79].

The bioavailability of triclabendazole, the drug of choice for fascioliasis, and total exposure to active metabolites were shown to be greatly increased by concomitant food intake [81]. Descriptive PK parameters were not different between fascioliasis patients and healthy subjects, indicating the absence of a disease effect on triclabendazole metabolism despite obvious liver damage [82].

Praziquantel, the anti-helminth drug of choice for both opisthorchiasis and clonorchiasis, appeared to have a reduced clearance rate in advanced opisthorchiasis infection, compared with early-stage disease and post-recovery, presumably owing to liver impairment [79]. In clonorchiasis patients, a sustained-release formulation was tested to allow for a single-dose treatment with praziquantel. Despite a similar area under the concentration-time curve, the sustained-release formulation with lower maximal concentration and peak time showed unsatisfactory efficacy compared with single-dose normal-release praziquantel [80].

Lymphatic Filariasis

Lymphatic filariasis, also known as elephantiasis, is a disfiguring disease caused by filarial nematodes (roundworms) and is a major cause of disability and social stigma in endemic areas. The filarial worms are transmitted by mosquitoes and cause an infection of the lymphatic system and skin, leading to massive edema formation in, for example, extremities and genitalia. Current treatment is generally through mass drug administration with the aim to stop transmission of the disease by killing the microfilarial stage of the parasite, using albendazole plus either ivermectin in regions with onchocerciasis (i.e., African countries) or albendazole plus diethylcarbamazine in all other regions. Pharmacokinetic studies in the context of lymphatic filariasis were found for both these combinations [83–85]. Doxycycline has been proposed as a treatment to kill also adult worms, but no PK studies could be identified for this drug in this context.

Co-administration of diethylcarbamazine and albendazole was investigated in healthy volunteers from areas where lymphatic filariasis is endemic [83]. Whereas large inter-individual variability in exposure of all drugs was observed, no significant interaction was detected. To assess the safety of albendazole mass drug administration during breast feeding, the pharmacokinetics of albendazole and metabolites was studied in the breast milk of treated women. Albendazole and albendazole sulfoxide achieved low penetration into breast milk and was not considered to be harmful for breastfed infants [85].

Onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness, is caused by the filarial nematode Onchocerca volvulus, which is transmitted through the bites of blackfly that breed near rivers. It results in various clinical manifestations, such as pruritus, subcutaneous nodules, onchocercal skin disease, and blindness. The therapeutic targets are the young microfilariae located, for example, in the skin, as well as the adult worms (macrofilariae) located generally in the subcutaneous nodules. The clinical approach to treatment is mainly focused on interrupting transmission through mass drug administration programs with ivermectin (focused on killing the microfilariae) at 6- to 12-monthly intervals, sometimes in combination with albendazole owing to an overlap with lymphatic filariasis co-infection. For individual treatment, doxycycline is used in combination with ivermectin. Various studies have investigated the pharmacokinetics of albendazole and ivermectin in onchocerciasis patients, focusing on dose-finding, food-effect, compliance, disease-effect, tissue distribution, and drug–drug interactions [86–90]. No PK studies were found for doxycycline. Other less established treatments include: suramin (too toxic and costly [91]), moxidectin (under development [92]), and amocarzine (insufficient efficacy [93, 94]).

Combining albendazole and ivermectin appeared to be safe and not to result in any PK interactions; albendazole co-administration offered no advantage over ivermectin alone in terms of efficacy against onchocerciasis [86, 87]. A fatty meal increased the bioavailability of albendazole fourfold and concomitant food intake should thus be recommended [86]. However, ivermectin pharmacokinetics was shown to be not affected by either food or alcohol intake [90].

Ivermectin PK parameters were similar between healthy volunteers and onchocerciasis patients and the drug was shown to penetrate in fat, skin, infected nodules, and even isolated parasites from these patients [89]. Compliance to non-observed ivermectin therapy in mass drug administration programs could be assessed through plasma concentration monitoring [88].

Pharmacokinetics of moxidectin, a veterinary anti-parasitic, was studied in healthy lactating women, including excretion into breast milk [92]. Moxidectin exposure in infants via breast milk was estimated to be 8.37 % of the maternal dose, but PK information from young children is necessary to fully understand the implications of this indirect exposure.

The bioavailability of amocarzine, an experimental drug for onchocerciasis, appeared to be poor in fasting conditions. Additionally, the dosing interval was suggested to be shortened to twice-daily administration to increase exposure [93]. A subsequent study showed improved bioavailability of amocarzine and exposure to its N-oxide metabolite with food intake [94].

Schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis is caused by Schistosoma blood flukes, whose life cycle is dependent on fresh water snails. Humans are infected through skin contact with contaminated water. The localization of the infection can vary depending on the infective Schistosoma species and can develop in the intestines, liver, spleen, lungs, bladder, or urinary tract. The acute phase is characterized by a transient hypersensitivity reaction associated with tissue migration of the larvae. Chronic infection can result in many different clinical manifestations such as hematuria (urogenital) or blood in the stool (intestinal), depending on the infected organs. Control of schistosomiasis is based on large-scale treatment mainly using praziquantel, which was the topic of most PK studies in schistosomiasis [16, 95–97]. The hepatic and renal dysfunction associated with chronic infection have been the focus of various praziquantel PK studies, which is hepatically metabolized and renally cleared. We also found descriptive PK studies for the experimental drugs metrifonate [98] and oxamniquine [99].

In one schistosomiasis case with chronic kidney failure, praziquantel plasma pharmacokinetics seemed not to be affected. This could indicate that advanced schistosomiasis can be treated with the regular praziquantel dose [95]. In patients infected by Schistosoma mansoni with various degrees of hepatic dysfunction, both the time to maximal concentrations as well as the area under the concentration-time curve increased proportionally with the degree of hepatic insufficiency [16]. Despite these PK differences, efficacy appeared not to be affected and dose adjustments based on hepatic function were not advised [16]. Pharmacokinetic parameters of two formulations of praziquantel were compared, to investigate a slower release formulation [96].

Soil-Transmitted Helminthiases

Soil-transmitted helminthiases are a diverse set of diseases caused by intestinal worms and often affect the most poor and rural communities. The main species that infect people through contact with contaminated soil are the roundworm (Ascaris), the whipworm (Trichuris), and the hookworms (Necator and Ancylostoma). Treatment for these infections is mainly through administration of antihelminths such as albendazole and mebendazole. Preventive treatment to reduce transmission to endemic populations is also widely used. No PK studies were identified.

Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika

Dengue is the most prevalent arthropod-borne viral disease. The Flavivirus infection can cause a wide range of clinical manifestations of which severe hemorrhagic dengue is potentially fatal. Chikungunya and zika, two other flaviviruses that are also transmitted by mosquitos, both cause acute febrile polyarthralgia and arthritis. There are no specific therapeutic treatments available for dengue, chikungunya, or zika, although a few vaccines are currently in development. However, no PK studies were identified for these viral infections.

Rabies

Rabies is caused by a range of lyssaviruses and usually starts with non-specific symptoms during the prodromal phase, but once a patient is symptomatic the infection usually leads to progressive encephalopathy and is virtually always fatal. There are no established antiviral treatment regimens for rabies, although various post-exposure prophylaxis schedules based on vaccine therapy with or without rabies-specific immunoglobulins are being used to prevent development of symptomatic disease. Some PK studies have been performed on the kinetics of administered anti-rabies antibodies [17, 18] and administered human interferon to support an early immune response [100].

Pharmacokinetics of human leukocyte interferon in CSF was compared between systemic and local intraventricular direct administration [100]. This study demonstrated that interferon levels in the CSF could be maintained at potentially therapeutically active levels, also by systemic administration. Two other studies looked at immunoglobulin antibody administrations to increase rabies antibody titers. In one study, two sources of equine rabies immunoglobulin were compared in terms of antigen-binding fragments, which showed similar time profiles, but no bioequivalence [17]. A phase I study with a recombinant human IgG1 anti-rabies monoclonal antibody determined the required dose to use in future post-exposure prophylaxis studies based on antibody pharmacokinetics [18].

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive and systematic review of clinical PK studies undertaken in the field of NTDs. Our study highlights the paucity of PK data available for the treatments used against NTDs and the lack of application of modeling and simulation techniques in this particular clinical area. For various NTDs (endemic treponematoses, dracunculiasis, dengue/chikungunya, and soil-transmitted helminthiasis), no PK studies could be identified at all, while for others only very few studies (<5) were found (Buruli ulcer, trachoma, echinococcosis, lymphatic filariasis, food-borne trematodiases, and rabies). For diseases such as soil-transmitted helminthiases and rabies, this lack of PK studies is in stark contrast to their massive global burden of disease (2700 and 26,400 deaths per year and 5.19 and 1.46 million disability-adjusted life-years, respectively). Whereas for some of these diseases dedicated chemotherapeutic options have never been available (e.g., dracunculiasis and dengue), for other NTDs, multiple drugs have been in clinical use for decades as part of established treatment guidelines, but information on PK studies is lacking. Owing to the consistent lack of research and development funding for treatment of NTDs, very little innovation has been witnessed in the past century for the management of NTDs. For example, suramin, pentamidine, and melarsoprol, which were discovered in 1920, 1940, and 1949, respectively, are still being used for human African trypanosomiasis and leishmaniasis management. For all of these drugs, no or very little PK studies have been performed since their introduction (we identified one, two, and five studies, respectively), while their live-threatening toxicities and the continuous threat of emerging drug resistance requires continued optimization of these dose regimens. The gap of knowledge on pharmacokinetics and PK–PD relationships limiting treatment optimization and adaptation has been highlighted before, e.g., for praziquantel [101] and schistosomiasis [102], but has largely been neglected for other NTDs previously.

Limitations

Because our systematic review focused on clinical PK studies, the term ‘pharmacokinetics’ was the most central search term in our analysis. However, this term itself was only been introduced in the field of pharmacology in 1953 by Dost and has been popularized in the two decades afterwards [103]. Given that several current drugs against NTDs have been in use for a few decades already, it could be that various older publications for these particular NTD drugs were not identified because they potentially did not make mention of the term ‘pharmacokinetics’. This might also explain that our two oldest identified studies date from 1980 [24, 98], which might thus be a biased observation. While drug development activities in the field of NTDs have substantially increased during the past 15 years, mainly through increased political awareness and novel innovation mechanisms such as the product development partnership Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (http://www.dndi.org), this appeared not to be reflected in the number of PK studies conducted. There is no particular increasing trend in the number of clinical PK reports for NTDs since 2000 (Fig. 2). On the contrary, more than half of all identified PK studies were published prior to 2000, with a peak of publications in the mid-1990s (seven studies in 1993). This might indicate that, despite innovative breakthroughs and increased clinical trial activities in the field of NTDs, PK studies are still being neglected; an observation corroborated by a recent review that found only 4/382 active clinical trials on NTDs directed at PK studies [9]. Regarding the type of PK analysis, there was an increasing trend of using a population approach to analyze the PK data over the past decade (Fig. 2).

A limitation in our search strategy was the English language restriction, potentially missing papers, e.g. in French from African journals or Chinese from Asian journals. Additionally, (national) journals from countries/regions where NTDs are endemic are not particularly well covered by PubMed/MEDLINE. Theoretically, this might have precluded our access to some literature, but given the topic of our literature analysis this potential bias is probably in reality very small or even non-existent and more relevant for clinical publications than PK publications.

While the list of NTDs used can be variable, the word ‘neglected’ in that term generally refers to the lack of interest from the pharmaceutical industry and the overall lack of funding and innovation in terms of therapeutic research and development for these diseases, but also to neglect by health ministries in countries where infected people live, by the World Bank, or relative to human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome, tuberculosis, and malaria. Typically NTDs are infectious diseases closely interrelated to poverty and socioecological systems promoting close contact between affected populations, vectors, and animal reservoirs. Malaria, tuberculosis, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome are not considered as NTDs. The list of NTDs has since the turn of the century often been expanded to more than 30 diseases and disease complexes [104]. We adhered to the list of NTDs put forward by the WHO [1], which contains 17 items of which various are disease ‘complexes’, such as ‘soil-transmitted helminthiases’, comprising multiple clinical infectious disorders.

Challenges in Clinical Pharmacokinetic Studies in Patients with Neglected Tropical Diseases

In the rural settings in which NTD clinical trials take place, collecting samples, maintaining cold chains, and generally performing large clinical trials are logistically challenging. Obtaining useful blood samples from patients can be practically difficult owing to a lack of laboratory infrastructure and restrictive clinical characteristics such as anemia. NTDs typically affect the poorest of the poor and disadvantaged populations, inherently constituting ethical difficulties, while language barriers and illiteracy make it difficult to acquire informed consent from patients. Additionally, following up patients after their treatment, e.g., to sample the elimination phase of a drug or identify long-term outcome, is often practically impossible, e.g., in nomadic populations. Moreover, there is limited research and development funding available for the clinical development of drugs for NTDs [9]. For all these reasons, clinical trials on NTDs therefore typically result in small and heterogeneous datasets. This is illustrated by our systematic review, as 94 % of the identified studies included small patient numbers (n < 50).

Patients in PK studies on NTDs are highly heterogeneous owing to variability in clinical characteristics such as degree of liver impairment, malnourishment, or concomitant underlying infections, which subsequently can lead to large inter-individual variability in PK parameters. Many studies in this review, e.g. almost all studies on cysticercosis and taeniasis [69, 70, 72–75], reported large inter-individual variabilities in PK profiles and parameters. That large unexplained inter-individual variability can limit conclusions of trials is also exemplified in our review. For instance, in one study on Buruli ulcer, no significant differences in PK parameters could be found between two treatment groups because of the small population size and high degree of inter-patient variability [55]. In another study on albendazole in echinococcosis, a dose-dependent increase of the active metabolite’s maximum plasma concentration could not be identified because of high intra- and inter-individual variability in bioavailability [78]. Furthermore, in the PK studies, some attention has been paid to drug–drug and food interactions (28 % of studies), but only a few studies (11 %) made suggestions for optimizing dosing. Furthermore, little attention has been paid to exposure-response relationships (6 % of studies), which is of high importance to make proper decisions regarding dosing schemes.

Advantages of Pharmacometric Techniques

To optimize treatment regimens and to design efficient and cost-effective clinical trials, the use of population-based analyses can provide substantial advantages. The US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency recommend the use of pharmacometrics in data analysis and clinical trial designs, especially in pediatrics or small patient groups [10–12]. Modeling and simulation techniques are pivotal in designing and simulating dosing regimens and trials and are a useful tool to extrapolate proposed regimens, e.g., from healthy to diseased populations. Particularly for pediatrics, the application of quantitative pharmacometric methods has been considered essential to increase the success rates of clinical trials [105]. Not only in a priori pediatric trial design, but particularly also in the a posteriori analysis of collected PK (and PD) data, pharmacometric methods are needed to deal with the typical pediatric challenges of small study populations and a low number of measurements [106]. For many NTDs, e.g., human African trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis, soil-transmitted helminthiases, schistosomiasis, and dengue, more than 50 % of the burden of disease is occurring in children [4].