Abstract

In the 1970s, groups of gay and gay-allied health professionals began to formulate guidelines for safer sexual activity, several years before HIV/AIDS. Through such organizations as the National Coalition of Gay Sexually Transmitted Disease Services, Bay Area Physicians for Human Rights, and the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, these practitioners developed materials that would define sexual health education for the next four decades, as well as such concepts as “bodily fluids” and the “safe sex hanky.” To do so, they used their dual membership in the community and the health professions. Although the dichotomy between the gay community and the medical establishment helped define the early history of HIV/AIDS, the creative work of these socially “amphibious” activists played an equally important part. Amid current debates over preexposure prophylaxis against HIV and Zika virus transmission, lessons for sexual health include the importance of messaging, the difficulty of behavioral change, and the vitality of community-driven strategies to mitigate risk.

Nearly 36 years after the first reports of immunosuppression among gay men, the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States continues to enter new epochs. The most recent is the age of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), the HIV prevention regimen whose implementation has sparked debates in the American Journal of Public Health and the Journal of the American Medical Association.1 Although PrEP could someday end HIV transmission, the epidemic continues, particularly among socioeconomically disadvantaged people, and condoms remain vital to preventing disease.

Meanwhile, debates about transmission of Zika virus—already dubbed “the millennials’ STD [sexually transmitted disease]”—have grabbed headlines in the New England Journal of Medicine and the New York Times.2 As practitioners of public health and community medicine confront old and new threats, the history of “safe sex”3 offers lessons for progress.

MAKING SEX SAFER: ROOTS IN THE 1970S

For all that has been written about HIV/AIDS and sexuality, the roots of safe sex in the 1970s, particularly in community physicians’ and psychologists’ response to hepatitis B virus (HBV) and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), remain buried. Here I use archival materials, original oral history interviews, and sources from popular and academic media to describe an amended timeline for the modern origins of safe sex. I also use this timeline to illustrate the roles of gay and gay-allied health professionals in responding to HIV/AIDS in the United States, especially in the earliest years of the epidemic.

These aims respond, in part, to two deficiencies in the social history of HIV/AIDS. The first is dating safe sex to the response to AIDS in the early 1980s rather than following its roots down to the response to HBV and other STIs in the 1970s. The second is overstating the dichotomy between laypeople and medical professionals. I use the work of gay and gay-allied health professionals in the 1970s and 1980s to argue that although HIV/AIDS created a tipping point for safe sex, the practices propagated in response to HIV/AIDS actually began with the response to HBV. Furthermore, I contend that although responses to HIV/AIDS grew partly out of tension between community members and health professionals, the work of people who identified with both groups—and whom I therefore call “amphibious” for their having “lived both ways”—is also central to the story of the epidemic.4

In 1996, Cindy Patton argued that “gay men’s collective history—including an affirmative view of the 1970s—formed a basis for, not an impediment to, new norms called ‘safe sex.’”5 This observation serves as a doorway to the period in question and its lessons for the present. As PrEP redefines HIV and Zika virus makes kissing scary again, issues such as risk stratification, community–professional alliances, and public health messaging remain as urgent as ever.

SAFE SEX: TWO ERAS, ONE ELUSIVE TRANSITION

The history of safe sex can be understood in terms of two periods. Prior to the late 1970s, the term and its associated practices were vaguely defined. By the late 1980s, a robust, consistent (if still heterogeneous) set of creeds and practices had emerged. This section examines those two periods and the transition between them.

First Era: Prehistory to the Late 1970s

Between 1979 and 1987, safe sex emerged from prehistoric limbo, transforming from a vague notion to front-page content. Something we might retrospectively call safe sex, however, is as old as art. Practices possibly intended to prevent conception appear in Dordogne frescoes from at least 10 000 BCE, showing what resembles a sheathed penis. Rubber condoms have been available, with restrictions, since the mid-19th century and latex ones since just before World War II.6

Prior to the 1980s, sex education in the United States emphasized protecting females from premarital conception and males from venereal disease. As Allan Brandt has written, US sexual education programs in the early 20th century “could be more accurately termed ‘antisexual education.’”7 Elizabeth Fee has described pioneering “sex hygiene” classes taught during World War II, with the message that “sex was both exciting and dangerous.” However, such instruction deemphasized intercourse itself.8 Jeffrey Moran’s study of US sex education hence depicts competing moral agendas, with an overarching “dominance of danger and disease”9 that was only amplified by AIDS. Materials from the 1960s and 1970s—including several that incorporate the phrase safe sex—emphasized heterosexual activity and contraception and seldom offered alternatives to abstinence and monogamy.10

For gay men, too, safe sex was inconsistently defined. A 1980 article on anonymous gay sexual encounters, for instance, defined safe sex as an encounter without violence.11 The monumental book Gay Men: The Sociology of Male Homosexuality, published in 1979, similarly defined “protection” as privacy rather than infection prophylaxis.12 In the late 1970s, Karla Jay and Allen Young completed a survey-based “gay report” totaling more than 800 pages, with only four pages devoted to STIs.13 This was life before AIDS; much changed in half a decade.

Second Era: AIDS and Safe Sex

By the mid-1980s, Patton has written, gay men were “America’s safe sex trendsetters.”14 The Advocate, a national LGBT (lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender) magazine dating to the 1960s, first promoted condoms in April 1983.15 In 1985, the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, in California, announced at the city’s annual Gay Pride March that “[t]here is no longer any excuse for unsafe sex.”16 In 1986, a written review of safe sex pamphlets included descriptions of 22 brochures.17

As the concept of safe sex went mainstream, homosexuality was largely left behind, as was HIV/AIDS, which is ironic given the role of the virus in the early propagation of safe sex. In April 1984, the same month HIV was publicly identified, Time magazine’s cover read “Sex in the ’80s: The Revolution Is Over,” with a cartoon Adam and Eve cowering beneath the headline.18 Inside, “HIV” and “AIDS” went unmentioned. By 1987, the long gestation of safe sex as a mainstream, heterosexual-relevant concept was essentially complete in both the popular and medical media.19 The February 1987 cover of the Atlantic Monthly depicted an opposite-sex couple in bed, looking nervous, with the legend “Heterosexuals and AIDS: the second stage of the epidemic.”20 Writings from this new era included Vern Becker’s Safe Sex, which argues that marriage is “the safest sex” and whose author “practices very safe sex with his wife.”21

In summary, from prehistory until 1979, safe sex heterogeneously emphasized avoidance of pregnancy and disease; by the early 1980s, it was newly defined in terms of risk reduction and sex positivity, especially for gay men, and would diffuse into mainstream culture by around 1987. I now turn to the story of the transition between these two eras.

INNOVATIONS OF THE 1970S: LAYING THE GROUNDWORK

Accounts of this transition are generally limited by two problems: starting too late, in the early 1980s, and overemphasizing the dichotomy between community members and health professionals. First, otherwise excellent secondary sources credit New Yorkers with creating the first guidelines around 1983,22 and typically leave out the work of the National Coalition of Gay Sexually Transmitted Disease Services (henceforth the National Coalition) and Bay Area Physicians for Human Rights (BAPHR),23 which played principal roles in the modern establishment of safe sex. Other sources, all excellent works by duly respected scholars, set the modern origin of safe sex in 1982 or later at the expense of groundwork dating at least three years earlier, pre-AIDS.24

Second, although the dichotomy between community members and medical professionals confronting the HIV/AIDS epidemic is duly emphasized in much of the early history of HIV/AIDS, its widespread overstatement obscures the full story. In many cases, as in the relationships between gay men and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Food and Drug Administration, and the National Institutes of Health, this polarization is largely accurate.25 However, such analyses also prevent acknowledgment that much of the response to HIV/AIDS has come from people who have confronted the epidemic as both gay men and medical professionals.

Looking past 1982 and into the years before AIDS, one approaches the true basis from which safe sex entered contemporary health practice: in gay and gay-allied physicians’ response to HBV and other STIs in the 1970s. Ephemera in the archives of the UCSF (University of California, San Francisco) AIDS History Project illustrate this work: as educational pamphlets on various STIs proliferated in the 1970s, the Resource Foundation hosted a “B Group” for people with HBV and their friends26; others held the first annual “Run-Walk-Crawl-a-thon” for HBV, in 1982.27 Just two years earlier, the CDC had rated HBV the foremost priority among STIs.28

HBV commanded attention for a simple reason: most other STIs could be treated with antibiotics but HBV could not, routinely leading to chronic hepatitis or liver cancer. Dr. Robert Bolan, who finished medical residency in 1975 and went to work at a clinic specializing in the treatment of venereal disease in men, recollected: “we focused on HBV because people die from that. As opposed to gonorrhea or syphilis: you treat it and you’re done . . . we all knew people with chronic HBV who died.”29 As rates of STIs skyrocketed in the gay community, health professionals heard a call to action.

In June 1979, the National Coalition, a gay-friendly and sex-positive consortium of physicians and other health professionals, began to develop guidelines to improve the safety of gay sexual behavior. Among the members of the National Coalition, numbering 71 by late 1982,30 Bolan is central to the story of safe sex because he happened to move to an epicenter of AIDS on the eve of the epidemic, with leadership roles before and after. Leaving Milwaukee, Wisconsin, for San Francisco in 1979, he brought the National Coalition draft guidelines to BAPHR, where they were expanded and disseminated when AIDS arrived.

Issue by issue, beginning in September 1979, the National Coalition newsletters reveal the development of these groundbreaking Guidelines and Recommendations for Healthful Gay Sexual Activity (henceforth Guidelines). The first newsletter references the goal of “developing a widely circulated statement supporting ‘responsible sexual behavior for gay people,’ especially for the purpose of promoting STD awareness & health care” and “developing a patient education packet on STDs for gay people.” This statement, the next issue adds, would be “published in the gay media, posted in bars, etc.” By 1980, the statement was known as Healthful Guidelines for Recreational Sex, under development by 13 members from throughout the United States, including David Ostrow in Chicago, Illinois, and Dan William in New York City, who soon became leading responders to AIDS.

By its fourth draft, in January 1981—five months prior to the first CDC report heralding AIDS—the document was politely retitled Guidelines and Recommendations for Healthful Gay Sexual Activity and deemed ready for circulation. These guidelines were “based on common sense, clinical observations, and/or empirical data.” They offered a positive definition of health as “more than the avoidance of STDs. It is the human condition in which the physical, mental, and emotional needs of a person are in balance.” The document concluded that “[h]ealthful sexual behavior is an expression of one’s natural sex drives in healthful, disease-free ways.”

The Guidelines also grouped various dimensions of sexual activity (context and frequency as well as behaviors) into three levels of risk and provided an instrument for calculating risk scores. The idea was to encourage people to replace riskier behaviors with safer ones. Local affiliates of the National Coalition developed their own versions of the Guidelines. Bolan, already lead author of the original document, revised a pamphlet for San Francisco via BAPHR, for example, and the Montrose Voice in Houston, Texas, likewise adapted a pamphlet from the Guidelines in April 1982.

In retrospect, Bolan called the Guidelines “our attempt to get the importance of STDs on the agenda.” He recalled: “what we tried to do with this document was to list all of the various STDs as we knew them and to honestly tell people what we knew about what behaviors put them at certain risks.” The authors’ ethos was democratic. Bolan recalled that “this document . . . comes from a health-education perspective of respecting your listener, which means not approaching them with any kind of a moralistic undercurrent to your message.”31 Advocating risk reduction in such a sex-positive manner was completely novel and created the template for responding to AIDS months later.

Pre-AIDS Safe Sex Messaging

Even with attempts at user friendliness, the reception for STI prevention was chilly prior to AIDS. As psychologist Peter Goldblum recalled, in the 1970s, safe sex “was there, but . . . it hadn’t [reached] the community level.”32 Community physician Patrick McGraw, who was central to HBV vaccine research in the 1970s, recalled giving talks about HBV prevention: “We knew condoms would help, but it was falling on deaf ears, largely.”33 STI rates suggested no change in the upward trend.

With HBV quietly devastating the community, the message needed to get out. And prior to AIDS, as its authors acknowledge, the Guidelines’ message was not getting through. “I knew back then,” Bolan recalled, “that if you’re speaking to gay men who highly value sex, you’ve got to speak in a sex-positive manner.”34 But ultimately, Bolan recalled, it took a group of drag nun activists to make his work accessible.

Before AIDS was labeled in 1981, BAPHR had connected with the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence (henceforth the Sisters), a San Francisco–based advocacy group founded in 1979 whose mission is “to promulgate universal joy and expiate stigmatic guilt.”35 The Sisters’ hallmark, as their name suggests, is transformation into drag nun personae—spiritual, playful, often controversial—for their activities.

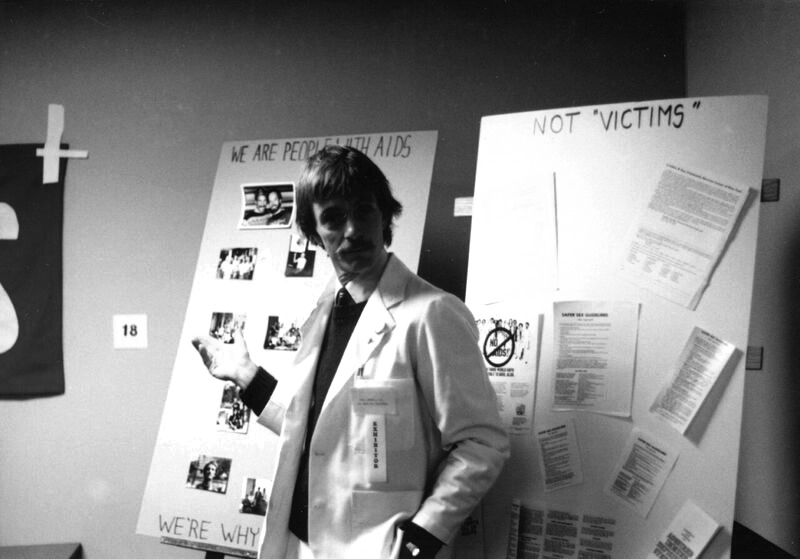

In a typical example of the crucial roles of gay health professionals in responding to AIDS, two registered nurses among the original Sisters, themselves deeply concerned about STIs among gay men, had begun to develop their own pamphlet, Play Fair! Although this pamphlet was prepared by a committee, its medical content came from registered nurses Bobbi Campbell (Sister Florence Nightmare) and Baruch Golden (Sister Roz Erection) in consultation with BAPHR physicians.36 Similar to the National Coalition and BAPHR, the authors of Play Fair! used their social citizenship in both the health professions and the gay community to drive the new response to HBV and other STIs and, soon after, to AIDS. An undated photograph of Bobbi Campbell in a white lab coat, in front of placards reading “WE ARE PEOPLE WITH AIDS” and “NOT ‘VICTIMS,’” exemplifies this dual belonging.37

Undated photograph of Bobbi Campbell. Printed with permission from the University of California, San Francisco.37

Play Fair!’s catalog of illnesses, composed when AIDS was rare, barely indicates the plague to come: “Gonorrhea, syphilis, herpes, scabies, intestinal parasites and hepatitis (not to mention widespread warts and guilt) have all reached epidemic proportions in San Francisco. Mysterious forms of cancer and pneumonia are now lurking among us too.” The language glides into total seriousness: “We are giving these diseases to ourselves and each other through selfishness and ignorance. We are destroying ourselves.” Hence “Mother Superior’s recommendations”: “playing fair” means, among other things, using condoms and avoiding sex if one has an STI.38

In June 1982, Play Fair! was distributed at Pride in San Francisco alongside the comparatively staid Guidelines. Apart from the obvious differences—the Guidelines lacked cartoons of frisky nuns with mustaches, for instance—the language of the two documents clearly represents their relationship. For example, the Guidelines warn that because “scented lubricants may [cause] a chemically induced proctitis (rectal inflammation), the use of hand lotions and other scented products for these purposes are discouraged.”39 Play Fair! translated that message: “buy lubricants free of fancy perfumes . . . the chemicals can inflame your ass.”40

National Coalition newsletters displayed constant revisions of both documents. Beginning with the second edition, completed in the summer of 1982, the Guidelines increasingly incorporated Kaposi’s sarcoma, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, and HIV/AIDS itself, bumping HBV and other STIs downstage.41 This, finally, is the period in which many historians have located the origin of safe sex, the era of Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz’s celebrated How to Have Sex in an Epidemic (1983),42 the Harvey Milk Gay Democratic Club’s Can We Talk? (1984),43 and similar materials.

Excerpt From Play Fair! Illustrating the Pamphlet’s Integration of Humor and Gravity. Printed with permission from the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.38

HBV to AIDS: New Behavioral Change Basis

In comparison with AIDS, death from HBV was rare and slow. To the recollections of doctors on the front lines, the dramatic impact of AIDS finally raised interest in changing sexual behaviors,44 as these physicians rapidly identified what appeared to be viral contagion. Paul Volberding recalled a “strong early rationale to safe sex”45 on this basis, despite the fact that the virus that became known as HIV was not publicly announced until 1984.

A recent epidemiological study of HBV helped lay the groundwork for this perspective; according to Gerald Oppenheimer, the association between HBV infection and numbers of sexual partners became a basis for the “lifestyle” hypothesis floated in the CDC’s earliest reports on AIDS.46 It is important to acknowledge the homophobic undercurrents of this hypothesis. As Steven Epstein has written, gay men’s “sexualized lifestyle was already depicted as medically problematic” in clinical literature,47 as revealed by phrases such as “homosexual hazards” and “gay bowel syndrome.” As they developed guidelines for the community, Bolan and his colleagues were contending with social stigma that preceded AIDS.

This HBV study offers one example of increased epidemiological attention to gay sex in the late 1970s; another is the Merck vaccine project. As Michelle Cochrane has argued: “increasing medicalization of gay men in the national hepatitis B vaccine trials of the late 1970s and early 1980s . . . preceded the emergence of the AIDS epidemic.”48 These changes also pertained to health professionals responding to STIs in the 1970s. McGraw, for example, recalled that when AIDS appeared, “we basically used hepatitis B as our prototype.”49 The substance of all of the guidelines that proliferated after 1981 therefore was basically the same as before AIDS, as designed by the National Coalition, disseminated by BAPHR, and translated for mass consumption by the Sisters. Year zero for modern safe sex is 1979, not 1982 or 1983.

Messaging 2.0

Even after AIDS, however, framing these concepts for the public remained challenging. A clarifying moment came at Lia Belli’s mansion in San Francisco’s Pacific Heights neighborhood during one of many community meetings after AIDS arrived. In a room full of doctors, a nonphysician, Paul Boneberg, stood up and said, “It sounds like you’re talking about exchange of bodily fluids.” Bolan vividly recalls this moment: “Those of us who were physicians looked around and said, ‘that’s exactly right’ . . . because we’d been struggling to come up with a really concise term so we could explain to people what you should be wary of: bodily fluids. . . . That concept, as it became incorporated into our language of safer sex, became the currency of the day: ‘no exchange of bodily fluids.’”50

Although the film Dr. Strangelove had famously used this phrase in 1964,51 a search of PubMed conducted in March 2016 shows 567 references to “bodily fluids.” Only three of these 567 references predate the approximate timing of the meeting at Belli’s mansion. The phrase seems to have entered medical science in the context of AIDS, possibly at the very meeting Bolan describes. Concerns about oversimplification and euphemism have accompanied the phrase since its adoption, but, as with safe sex, its extensive usage testifies to its value as convenient shorthand.

Such pragmatic framing reflected a goal of remaining sex positive, to give the public guidelines that honored the basic human need for sex. On this basis, Bolan recalls relying not on the existing heterosexist guidelines emphasizing marital fidelity and contraception but on

Smoking cessation guidelines, and overeating guidelines . . . because I viewed the challenge of convincing someone to change their sexual behavior as fundamentally biological a challenge as getting people to stop smoking, stopping an addicting drug, or reducing their weight, a biological drive, eating. So I just knew right in my gut that we really needed a new educational paradigm.52

This “new paradigm” was partly rooted in the most intense loci of sexual activity: the leather community, transactional sex, and pornography. Berkowitz recalled that after AIDS, transactional sadomasochism—which already required negotiation of everything from prices to specific acts—improvised modes of communication to incorporate safe sex.53 In work that cited BAPHR guidelines, Richard Locke, a pornographic actor and safe sex advocate, promoted lower-risk practices.54 Psychologist Bill Woods recalled integration of sadomasochism tenets into safe sex advocacy:

Because they had a history and a culture of formalizing things, and negotiating things, and having language for [sexual activity] at a time when most gay men didn’t have any of those things [it was helpful] to pull that from the leather community.55

The navigation of anonymous sexual encounters in public spaces already required what Patton has called the “minimalist vernaculars of cruising,”56 an idiom whose grammar readily integrated safety. “Hanky codes,” in which displays of different handkerchiefs indicate desired sexual activities, were a natural locus for safe sex communication. Hence, the flyer for the “Safe Week” held in May 1981 in Denver, Colorado, featured a cartoon of “Le Hunk Safe,” who appears to have a checkered hanky—the safe sex hanky—in his right back pocket.57 This may be the first clearly dateable instance of the “safe hanky,” notably preceding the CDC’s AIDS-heralding reports of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and Kaposi’s sarcoma and supporting the argument that safe sex was culturally reified before AIDS.

“Le Hunk Safe” Sporting a Checkered Hanky. Printed with permission from the National Coalition of Gay Sexually Transmitted Disease Services and the Denver Health and Hospital Authority.57

A final memory spotlights the location of safe sex innovation in the overlap of the community and the health professions. Bolan recalled that in the early 1980s, when he was president of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, “we did a safe sex porn.” Such work was increasingly common; unusually, here the sponsor insisted that Bolan introduce the action, on camera. “They wanted me sitting on a stool, fully clothed, introducing the safe sex video, and I said, ‘This is porn, you don’t want a doctor lecturing to you!’ And they said, ‘Do you want the money?’ So I did it!” To Bolan, who had written the earliest modern safe sex guidelines and had met with Kinsey Institute specialists to discuss eroticization of condoms, the “safe sex pornography” idea seemed reasonable: “I wasn’t dubious about the porn video; I was dubious about introducing it. Let the thing speak for itself!”58

Returning to the present, the same tensions between medicalization and popularization and between safety and fulfillment appear in the propagation of PrEP and the new menace of Zika virus. Bolan himself had doubts before the IPERGAY trial59 supported the effectiveness of intermittent adherence to antiretroviral prophylaxis, but he now sees PrEP as a potential means to end AIDS. Meanwhile, the spread of Zika virus demands risk stratification and education for behavioral change. Zika virus differs from HIV in an important regard: while men who have sex with men have been disproportionately affected by HIV, it is not clear whether an analogous community will emerge to propel the fight against Zika virus.60 Women (especially health professionals) of reproductive age would be an obvious demographic to play this role. But the form and style of the response to Zika virus remain uncertain, as does the magnitude of the epidemic itself. One lesson from the early years of AIDS appears to be that people change sexual behaviors when they experience personal danger or loss, but not before.

Several aspects of safe sex innovation illustrate principles necessary to engage the public on current sexual threats to public health. By identifying bodily fluids as a concern, community leaders created shorthand that laypeople could understand. The origins of the checkered hanky show that the portions of a community at highest risk—here, those engaging in cruising—might also be exactly the people to innovate solutions via existing subcultural idioms. Bolan’s prefatory “safe sex porn” discourse exemplifies the incorporation of education into loci of hedonism. Finally, these examples of creative health practices show the power of “amphibian” civilian-professionals who “live both ways,” in roles that are not hybrid but innately dual. Their simultaneous citizenship in the gay and medical communities enabled them to innovate safe sex guidelines and begin to market them effectively before AIDS even arrived.

As health promotion progresses, implementation of accessible language, adaptation of existing idioms, and action by population-bridging agent-advocates—people who are both exceptionally affected by an epidemic and empowered with content expertise—remain fundamental. If sexual health promotion is to remain politically effective, sex positive, and socially just, its agents must continue to incorporate these principles.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Joel Braslow (University of California, Los Angeles) and Dorothy Porter (University of California, San Francisco) for research supervision; the staff of the University of California, San Francisco, AIDS History Project, especially David Uhlich; the staff of the University of California, Berkeley, Regional Oral History Office at the Bancroft Library; and the many heroes of the HIV/AIDS epidemic who have given generously of their time and memories for this study.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, Los Angeles, and participants provided informed consent.

ENDNOTES

- 1. S. K. Calabrese and K. Underhill, “How Stigma Surrounding the Use of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Undermines Prevention and Pleasure: A Call to Destigmatize ‘Truvada Whores,’” American Journal of Public Health 105, no. 10 (2015): 1960–1964; K. H. Mayer, D. S. Krakower, and S. L. Boswell, “Antiretroviral Preexposure Prophylaxis: Opportunities and Challenges for Primary Care Physicians,” Journal of the American Medical Association 315, no. 9 (2016): 867–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2. F. M. Folkers, “Zika: The Millennials’ STD?” http://mobile.nytimes.com/2016/08/21/opinion/sunday/zika-the-millennials-std.html (accessed March 4, 2017); E. D’Ortenzio, S. Matheron, Y. Yazdanpanah, et al., “Evidence of Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus,” New England Journal of Medicine 374, no. 22 (2016): 2195–2198.

- 3. Although “safe sex” oversimplifies the crucial point of risk stratification by implying that “safety” is binary, I defer to standard usage and expedience by henceforth using the term without quotation marks.

- 4. T. R. Blair, “Plague Doctors in the HIV/AIDS Epidemic: Mental Health Professionals and the ‘San Francisco Model,’ 1981–1990,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 90, no. 2 (2016): 279–311. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5. C. Patton, Fatal Advice (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996), 111.

- 6. E. Chevallier, The Condom (London, UK: Penguin Books, 1993).

- 7. A. M. Brandt, “AIDS: From Social History to Health Policy,” in E. Fee and D. M. Fox, eds., AIDS: The Burdens of History (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988), 151.

- 8. E. Fee, “Sin Versus Science: Venereal Disease in Twentieth-Century Baltimore,” in E. Fee and D. M. Fox, eds., AIDS: The Burdens of History (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988), 137.

- 9. J. Moran, Teaching Sex (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

- 10. Examples of this usage include D. Cossey, Safe Sex for Teenagers (London, UK: Brook Advisory Centers, 1978), and J. S. Golden and C. Mason, “The Doctor and Sex Education,” Western Journal of Medicine 115, no. 4 (1971): 60–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11. B. Miller and L. Humphreys, “Lifestyles and Violence: Homosexual Victims of Assault and Murder,” Qualitative Sociology 3, no. 3 (1980): 169–185.

- 12. M. P. Levine, ed., Gay Men: The Sociology of Male Homosexuality (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1979).

- 13. K. Jay and A. Young, The Gay Report (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1977). Jay and Young would soon use the same Gay Report data to complete a massive contribution to the epidemiology of STIs among gay men.

- 14. Patton, Fatal Advice, 3.

- 15. J.-M. Andriote, Victory Deferred (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

- 16. R. Shilts, And the Band Played On (New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1987), 569.

- 17. K. Siegel, P. B. Grodsky, and A. Herman, “AIDS Risk-Reduction Guidelines: A Review and Analysis,” Journal of Community Health 11, no. 4 (1986): 233–243. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18. “Sex in the ’80s: The Revolution Is Over” (cover), Time, April 9, 1984.

- 19. J. J. Goedert, “What Is Safe Sex? Suggested Standards Linked to Testing for Human Immunodeficiency Virus, New England Journal of Medicine 316, no. 21 (1987): 1339–1342. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20. “Heterosexuals and AIDS: The Second Stage of the Epidemic” (cover), Atlantic Monthly, February 1987. For further discussion of HIV/AIDS, gender, and media in the 1980s, see P. Treichler, How to Have Theory in an Epidemic (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999).

- 21. V. Becker, Safe Sex (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1989), 31.

- 22. M. Cochrane, When AIDS Began (New York, NY: Routledge, 2004). See also R. Berkowitz, Stayin’ Alive (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2003).

- 23. National Coalition of Gay Sexually Transmitted Disease Services. Official Newsletter of the NCGSTDS, 1981, vol. 3, no. 2, http://chodarr.org/sites/default/files/chodarr2870.pdf (accessed March 4, 2017)

- 24. Patton, Fatal Advice; E. King, Safety in Numbers (New York, NY: Routledge, 1993); D. Altman, AIDS in the Mind of America (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1986); S. Brier, Infectious Ideas (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

- 25. S. Epstein, Impure Science (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996).

- 26. Resource Foundation. UCSF AIDS History Project Archive, https://www.library.ucsf.edu/archives/aids (accessed March 4, 2017)

- 27. First Annual Run-Walk-Crawl-a-thon (flyer), UCSF AIDS History Project archive, 1982.

- 28. R. K. Bolan, “Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Homosexuals: Focusing the Attack,” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 8, no. 4 (1981): 293–297. [PubMed]

- 29. R. K. Bolan, personal interview, February 23, 2016.

- 30. National Coalition of Gay Sexually Transmitted Disease Services. Official Newsletter of the NCGSTDS. 1982, vol. 4, no. 2, http://chodarr.org/sites/default/files/chodarr2876.pdf (accessed March 4, 2017). The newsletter citations that follow are from volumes 1–3 (1979–1981)

- 31. S. S. Hughes, interview with R. K. Bolan, San Francisco AIDS Oral History Series. Quoted with permission, http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt1489n6h0&brand=calisphere&doc.view=entire_text (accessed March 4, 2017)

- 32. P. Goldblum, personal interview, January 6, 2012.

- 33. P. McGraw, personal interview, February 14, 2012. Although reliable longitudinal data had yet to be collected and analyzed, the unpopularity of safety measures prior to AIDS is a matter of total consensus among this study’s interviewees.

- 34. R. K. Bolan, personal interview, February 23, 2016.

- 35. K. Bunch, personal interview, June 1, 2016.

- 36. C. Brayton, personal interview, May 9, 2016; K. Bunch, personal interview, June 1, 2016; B. Golden, personal interview, May 6, 2016; R. Stine, personal interview, May 26, 2016.

- 37. Undated photograph of Bobbi Campbell. UCSF AIDS History Project, University of California, San Francisco Library.

- 38. Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, Play Fair! (San Francisco, CA: Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, 1982).

- 39. National Coalition of Gay Sexually Transmitted Disease Services. Official Newsletter of the NCGSTDS. 1981, vol. 2, no. 3, 14, http://chodarr.org/sites/default/files/chodarr2870.pdf (accessed March 4, 2017)

- 40. Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, Play Fair!

- 41. National Coalition of Gay Sexually Transmitted Disease Services. Official Newsletter of the NCGSTDS. 1982, vol. 4, no. 2, http://chodarr.org/sites/default/files/chodarr2876.pdf (accessed March 4, 2017)

- 42. M. Callen and R. Berkowitz, How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: One Approach (New York, NY: Tower Press, 1983).

- 43. Harvey Milk Lesbian & Gay Democratic Club, Can We Talk? (San Francisco, CA: Harvey Milk Lesbian & Gay Democratic Club, 1984).

- 44. P. Volberding, personal interview, January 9, 2012.

- 45. Ibid.

- 46. G. Oppenheimer, “Causes, Cases, and Cohorts: The Role of Epidemiology in the Historical Construction of AIDS,” in E. Fee and D. M. Fox, eds., AIDS: The Making of a Chronic Disease (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1992).

- 47. Epstein, Impure Science, 50.

- 48. M. Cochrane, When AIDS Began (New York, NY: Routledge, 2004), xxiv. See also Patton, Fatal Advice, and Andriote, Victory Deferred.

- 49. P. McGraw, personal interview, February 14, 2012.

- 50. R. K. Bolan, personal interview, February 23, 2016.

- 51. S. Kubrick, Dr. Strangelove; or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Culver City, CA: Columbia TriStar Home Entertainment, 1964).

- 52. R. K. Bolan, personal interview, February 23, 2016.

- 53. Berkowitz, Stayin’ Alive.

- 54. R. Locke, In the Heat of Passion (San Francisco, CA: Leyland Publications, 1987).

- 55. W. Woods, personal interview, April 12, 2012.

- 56. Patton, Fatal Advice.

- 57. National Coalition of Gay Sexually Transmitted Disease Services. Official Newsletter of the NCGSTDS. 1981, vol. 3, no. 2, http://chodarr.org/sites/default/files/chodarr2870.pdf (accessed March 4, 2017)

- 58. R. K. Bolan, personal interview, February 23, 2016.

- 59. J. M. Molina, C. Capitant, B. Spire, et al., “On-Demand Preexposure Prophylaxis in Men at High Risk for HIV-1 Infection,” New England Journal of Medicine 373, no. 23 (2015): 2237–2246. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60. I am indebted to an anonymous reviewer for this point.