Abstract

Objectives. To examine the health insurance coverage options for Medicaid expansion enrollees if the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is repealed, using evidence from Ohio, where more than half a million adults have enrolled in the state’s Medicaid program through the ACA expansion.

Methods. The Ohio Medicaid Assessment Survey interviewed 42 000 households in 2015. We report data from a unique battery of questions designed to identify insurance coverage immediately prior to Medicaid enrollment.

Results. Ninety-five percent of new Medicaid enrollees in Ohio did not have a private health insurance option immediately before enrollment. These new enrollees are predominantly older, low-income Whites with a high school education or less. Only 5% of new Medicaid enrollees were eligible for an employer-sponsored insurance plan to which they could potentially return in the case of repeal of the ACA.

Conclusions. The vast majority of Medicaid expansion enrollees would have no plausible pathway to obtaining private-sector insurance if the ACA were repealed. Demographic similarities between the expansion population and 2016 exit polls suggest that coverage losses would fall disproportionately on members of the winning Republican coalition.

Numerous press outlets have labeled the election of Donald Trump as “the revenge of working class Whites.”1,2 According to the Washington Post, White voters without a college degree “were the foundation of [Trump’s] victories across the Rust Belt, including a blowout win in Ohio and stunning upsets in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.”1 This same demographic benefits disproportionately from the health insurance coverage provided through the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s; Pub L No. 111–148) Medicaid expansion. It is perhaps surprising, then, that a centerpiece of President Trump’s campaign was his vow to press for a “full repeal” of the ACA (“Obamacare”) on “day one.”3

It is unclear whether Congress will indeed pursue a full repeal of the ACA (which would require 60 votes in the Senate unless the filibuster rule is changed), but it is likely that Congress will act to substantially restructure the ACA. If the ACA is fully or partially repealed, who would lose their coverage and what would happen to them? Using data from Ohio (2015 Ohio Medicaid Assessment Survey, or OMAS), we try to answer those questions by examining what is known about those insured through the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and what their health insurance coverage was before they enrolled. These data indicate that 95% of new Medicaid participants had no private insurance option when they enrolled, and that a rollback of the expansion would predominantly affect older, low-income Whites with less than a college education—in other words, key members of the new Republican coalition.

A centerpiece of the ACA’s effort to reduce the number of uninsured Americans was its expansion of Medicaid. In states that elected to expand Medicaid, all adults with incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) are now eligible for enrollment. (The 2015 FPL for an individual was $11 770; 138% of the FPL was approximately $16 243.) In Ohio, prior to the ACA, childless adults were generally ineligible for Medicaid unless pregnant or disabled, and parents qualified for Medicaid only if their family income was below 90% of the FPL. For this report, we therefore define the 2015 Medicaid expansion population as individuals with Ohio Medicaid coverage who were (1) childless adults in families earning less than 138% of the FPL or (2) parents with family incomes between 90% and 138% of the FPL.

Ohio’s Medicaid expansion took effect on January 1, 2014. During the first 18 months of the program (by completion of the OMAS in June 2015), 626 000 individuals enrolled in Ohio Medicaid through the expansion.4 By October 2016, enrollment had reached 712 000 individuals.5 A recent analysis by the Ohio Department of Medicaid (in which we assisted) concluded that Ohio’s Medicaid expansion increased access to medical care for enrollees, reduced unmet medical needs, improved self-reported health status, and alleviated financial distress.6 All of these results confirm findings from other states that have expanded Medicaid.7

In the case of a Medicaid rollback, what would be the coverage options for the new enrollees? The coverage impact of a large-scale Medicaid rollback is uncharted territory, but policymakers have 20 years of evidence indicating how insurance markets respond to coverage expansions. Most studies focused on Medicaid expansions for children and found that up to 50% of newly eligible children dropped a private plan to enroll in the newly available public coverage (crowd-out). Other studies have found lower but still positive crowd-out rates for children.

METHODS

To determine who would lose coverage in a Medicaid rollback, we used the 2015 OMAS (n = 42 876 households), with additional data from the 2012, 2010, and 2008 survey iterations. (The name of the survey was changed from the Ohio Family Health Survey in 2012.) Data collection for the 2015 survey took place from January through June 2015. Each survey captured respondents’ insurance, self-reported health status, health care utilization, and other key population health determinants.8

The OMAS is a dual-frame (landline and cellular phone), computer-assisted telephone survey. The dual-frame methodology allows for more precise estimates for both younger and low-income households that increasingly rely solely on cell phone service. All iterations of the survey oversample African Americans and Hispanics and interviews are conducted in both English and Spanish. The overall response rate (response rate 3, or RR3) for the 2015 OMAS was 24.1%.

The OMAS includes a unique battery of questions to identify coverage immediately before Medicaid enrollment. The insurance coverage begins with a standard question to identify the respondent’s primary coverage. For all adults with Medicaid, a second question asks how long they have been covered by Medicaid. Individuals enrolled for less than 12 months are asked whether they had insurance before enrolling in Medicaid. If they were insured before their current Medicaid coverage, a follow-up question records the type of coverage. This series of questions allowed us to determine coverage, or lack of coverage, immediately preceding enrollment in the Medicaid expansion.

The OMAS allows respondents to report multiple types of health insurance. For this study, we created a hierarchical insurance variable of coverage at the time of the survey, in which Medicaid coverage takes precedence. We coded individuals reporting a private source of coverage as having private insurance only if they were not also enrolled in government-sponsored coverage. We excluded individuals with dual Medicaid and Medicare coverage from the analysis. Similarly, we focused on adults aged 18 to 64 years and excluded senior citizens.

RESULTS

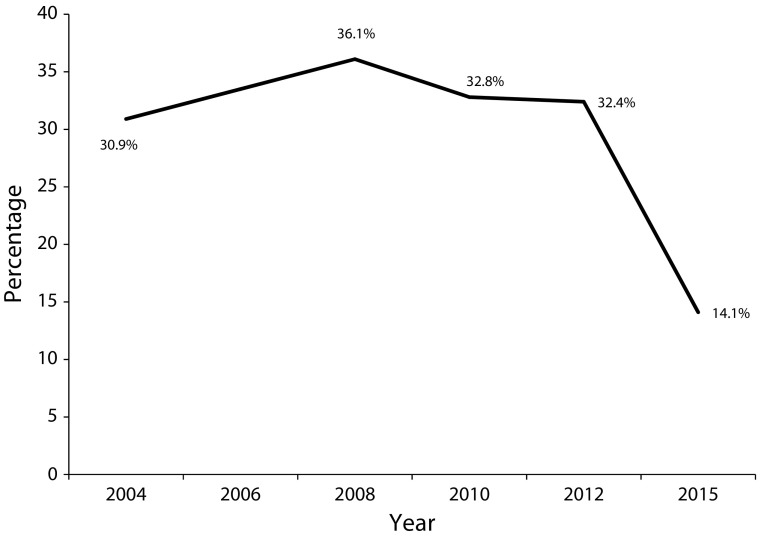

Ohio’s Medicaid expansion coincided with a dramatic decline in the uninsured rate for low-income adults. As shown in Figure 1, Ohio’s uninsured rate for adults with family incomes at or below 138% of the FPL was 31% in 2004, and then peaked at 36% during the Great Recession before stabilizing around 32% in 2010 and 2012. By mid-2015, 18 months after Ohio expanded Medicaid, the uninsured rate for low-income adults had dropped by half to 14.1%. The reductions in the uninsured rate and increases in Medicaid coverage observed in the survey data were also reflected in Ohio Medicaid administrative data. From January 2014 to June 2015, 625 000 nonsenior adults enrolled in Ohio’s Medicaid expansion.4

FIGURE 1—

Uninsured Rates of Nonelderly Adults With Incomes at or Below 138% of the Federal Poverty Level: Ohio, 2004–2015

Source. Ohio Medicaid Assessment Survey, 2004–2015.

Table 1 details prior insurance status for Ohio adults who were enrolled in Medicaid for less than 12 months and who met the ACA expansion eligibility thresholds. For these new Medicaid enrollees, 17.7% had private health insurance immediately prior to enrolling in Medicaid. Of those 17.7%, almost all (16.6%) had employer-sponsored insurance, and another 1.1% had a privately purchased individual plan.

TABLE 1—

Expansion-Eligible Adult Respondents to Survey Who Had Enrolled in Medicaid Within the Past 12 Months: Ohio, 2015

| Insurance Status Before Switching to Medicaid | % of Respondents (95% CI) |

| Employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) | 16.6 (13.1, 20.2) |

| Other private insurance | 1.1 (0.0, 2.2) |

| Any private insurance | 17.7 (14.1, 21.4) |

| Respondent was unemployed | 8.7 (6.1, 11.3) |

| No one in household was employed | 6.2 (4.1, 8.4) |

| Respondent was self-employed | 0.7 (0.0, 1.4) |

| Respondent had ESI | 6.7 (4.0, 9.3) |

| Respondent was eligible for ESI | 4.8 (2.4, 7.3) |

| Respondent could afford ESI | 4.0 (1.7, 6.3) |

Note. CI = confidence interval. The number of respondents was 727. We excluded from the analysis individuals with dual Medicaid and Medicare coverage.

Source. Ohio Medicaid Assessment Survey, 2004–2015.

Although 17.7% of new Medicaid enrollees had private insurance prior to Medicaid, most of them involuntarily lost their private coverage. Table 1 shows that most of these individuals transitioned to Medicaid because of unemployment. Of the 17.7% that previously had private coverage, 8.7% (almost half) were unemployed at the time they enrolled in Medicaid. Another 6.7% (about one third) worked for an employer who sponsored a group health insurance plan, but just 4.8% were eligible for that plan. In sum, 95.3% of Medicaid expansion enrollees (1) did not have private health insurance prior to Medicaid, (2) lost their prior coverage through unemployment, or (3) did not qualify for their employer’s health plan.

Table 1 also examines affordability. Of the 4.8% of new Medicaid enrollees who were still eligible for their employer-sponsored group plan, 0.8% indicated that they did not participate because it cost too much. Only 4.0% of all new Medicaid enrollees were eligible for an employer-sponsored insurance plan that they considered affordable.

Demographic information collected as part of the OMAS (Table 2) shows that the average Ohio Medicaid expansion enrollee was almost 40 years old (58% were older than 35 years), and by design, Medicaid expansion enrollees had family incomes at or below 138% of the FPL. More than two thirds of Medicaid expansion enrollees identified themselves as White, and more than half (59%) had a high school education or less.

TABLE 2—

Demographic Characteristics of Adult Enrollees of Medicaid Expansion and Federal Exchange: Ohio, 2015

| Characteristic | 2015 Medicaid Expansion (n = 725) | 2015 Marketplace (n = 688) |

| Age, y, Mean (95% CI) | 39.0 (37.8, 40.2) | 49.0 (47.7, 50.3)* |

| Age category, % (95% CI) | ||

| 19–27 | 25.3 (20.9, 29.8) | 10.0 (6.8, 13.2)* |

| 28–34 | 17.2 (13.4, 21.1) | 10.9 (7.7, 14.2) |

| 35–44 | 20.0 (16.1, 23.9) | 11.2 (8.1, 14.3)* |

| 45–54 | 22.3 (18.7, 25.9) | 23.7 (19.7, 27.6) |

| 55–65 | 15.2 (12.5, 17.8) | 44.3 (39.8, 48.8)* |

| Race/ethnicity, % (95% CI) | ||

| White | 68.2 (63.7, 72.7) | 89.2 (86.3, 92.1)* |

| Black or African American | 24.8 (20.5, 29.1) | 7.1 (4.7, 9.4)* |

| Asian | 1.5 (0.1, 2.8) | 2.2 (0.7, 3.7) |

| Hispanic | 4.6 (2.8, 6.4) | 1.2 (0.4, 1.9)* |

| Female, % (95% CI) | 49.6 (44.9, 54.3) | 52.9 (48.3, 57.6) |

| Married, % (95% CI) | 19.8 (16.2, 23.4) | 51.6 (47.0, 56.3)* |

| Education, % (95% CI) | ||

| < high school | 18.0 (14.2, 21.7) | 3.4 (1.5, 5.4)* |

| High school graduate | 41.4 (36.8, 45.9) | 33.7 (29.3, 38.0) |

| Some college | 34.2 (29.5, 38.8) | 33.1 (28.6, 37.6) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 6.4 (4.3, 8.4) | 29.5 (25.5, 33.5)* |

| Self-reported health status, % (95% CI) | ||

| Excellent or very good | 33.4 (28.8, 38.0) | 55.2 (50.7, 59.8)* |

| Good | 34.1 (29.7, 38.6) | 31.0 (26.7, 35.3) |

| Fair or poor | 32.5 (28.2, 36.7) | 13.7 (10.7, 16.8)* |

| Family income, % (95% CI) | ||

| ≤ 138% of FPL | 100.0 | 17.4 (13.8, 21.1)* |

| 139%–200% of FPL | . . . | 22.2 (18.4, 26.0)* |

| 201%–300% of FPL | . . . | 25.2 (21.2, 29.2)* |

| > 300% of FPL | . . . | 35.2 (30.8, 39.6)* |

| Employed at time of interview, % (95% CI) | 45.6 (40.9, 50.3) | 68.5 (64.3, 72.7)* |

| Employed by a firm with ≤ 50, % (95% CI) | 16.8 (13.5, 20.1) | 50.6 (46.0, 55.2)* |

| County type, % (95% CI) | ||

| Suburban | 12.3 (9.2, 15.3) | 13.6 (10.7, 16.4) |

| Non-Appalachian rural | 8.1 (5.8, 10.4) | 13.3 (10.2, 16.3) |

| Metro | 64.7 (60.4, 69.0) | 54.6 (50.1, 59.2)* |

| Appalachian | 14.9 (11.9, 17.9) | 18.5 (15.1, 22.0) |

Note. FPL = federal poverty level; CI = confidence interval.

Source. Ohio Medicaid Assessment Survey, 2004–2015.

P = .05 (significant difference between Medicaid expansion and marketplace samples).

Although not the primary focus of this study, it should be noted that the demographics of Ohio’s ACA exchange participants showed some similarities to those of Medicaid expansion enrollees. By design, exchange participants had higher income levels than Medicaid expansion enrollees, but they were similarly older (with an average age of 49 years) and were almost exclusively White (89%).

DISCUSSION

Data from the 2015 OMAS provide suggestive evidence of what would happen if policymakers decided to roll back the Medicaid expansion. First, unless some new health care option is provided in its place, most of the people who have enrolled in Medicaid through the expansion would be left without any realistic avenue for obtaining health insurance. Of those who enrolled in the exchange, 95% had no private insurance option when they enrolled. Although it is possible that some portion of these enrollees have since been hired by an employer that offers an employer-sponsored insurance, it is unlikely that this would meaningfully improve the insurance outlook for this population. Because of the low incomes of the expansion population, previous research suggests that many would not be able to afford an employer-sponsored insurance plan, even if one were available.9

Second, those who would lose coverage in a Medicaid expansion rollback would be disproportionately White, middle-aged, and with a high school diploma or less. The loss of coverage for these individuals would threaten to reverse the significant improvements in financial security and access to health care that Medicaid expansion has provided.7 In Ohio, a rollback of the Medicaid expansion would be substantially more disruptive than discontinuing the federal exchange (Table 1). Although Ohio enrollment in the federal exchange was by no means trivial—188 223 paid enrollees as of June 2015 according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services10—it was considerably less that the number enrolled through Medicaid expansion. Put differently, between the 2012 and 2015 OMAS, Medicaid participation increased from 9.7% to 18.5% of Ohio’s adult population, whereas only 2.3% of adults reported participating in a new marketplace plan in the 2015 OMAS.

When Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-WI) chaired the House Budget Committee, his committee staff asserted that “government-provided health care in the form of Medicaid has been shown to reduce private-insurance participation” and that “people are enrolling in taxpayer-funded Medicaid despite having access to private health insurance.”11 Although the results in other states might be different, this analysis suggests that these claims are unfounded in Ohio. Very few individuals participating in Ohio’s Medicaid expansion had potential access to private health insurance at the time they enrolled. More than 80% of new enrollees had no prior insurance whatsoever, and most of the rest had recently lost their employer-provided coverage.

Limitations

Decreasing response rates are an important limitation for all household telephone-based surveys. Concerns about these declining response rates date back more than a decade.12 The response rates for large, nonfederal household telephone surveys commonly range from 12% to 30%.13 The 2015 OMAS is in the middle of this range, with a combined response rate (RR3) of 24.1%. To minimize the risk of sampling bias, the OMAS uses a complex survey design that oversamples key demographic groups and weights responses to match Ohio’s demographics in the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.14

Conclusions and Implications

If the ACA were repealed, the vast majority of Medicaid expansion enrollees would have no current plausible pathway to obtaining private-sector insurance. Moreover, the demographics of those who would lose coverage if Medicaid expansion is undone suggest an interesting political dynamic. Exit polls from the 2016 election indicate that President Trump’s victory depended on support from middle-aged White voters (particularly men) with lower levels of education. Indeed, roughly 70% of White men without a college degree voted for Trump.15 Republicans overall benefited from greater vote margins than in previous elections among older, White, less-educated, low-income households.16 This demographic closely matches enrollment in Ohio’s Medicaid expansion. Thus, in addition to reversing gains in health insurance coverage, Republicans might risk electoral backlash if they follow through with their plan to repeal the ACA.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study used publicly available, de-identified data. No human participants were involved in the research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tankersley J. How Trump won: the revenge of working-class whites. Washington Post. November 9, 2016. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/11/09/how-trump-won-the-revenge-of-working-class-whites/?utm_term=.8c04197093dd. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 2.Cohn N. Why Trump won: working-class whites. New York Times. November 9, 2016. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/10/upshot/why-trump-won-working-class-whites.html?_r=1. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 3.Trump DJ. Healthcare reform to make America great again. Available at: https://www.donaldjtrump.com/positions/healthcare-reform. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 4.Ohio Dept of Medicaid. Caseload reports. Available at: http://medicaid.ohio.gov/Portals/0/Resources/Reports/Caseload/2015/10-Caseload.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 5.Ohio Dept of Medicaid. Caseload reports. Available at: http://medicaid.ohio.gov/Portals/0/Resources/Reports/Caseload/2016/10-Caseload.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 6.Ohio Dept of Medicaid. Ohio Medicaid Group VIII Assessment: A Report to the General Assembly. 2016. Available at: http://medicaid.ohio.gov/Portals/0/Resources/Reports/Annual/Group-VIII-Assessment.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 7.Antonisse L, Garfield R, Rudowitz R, Artiga S. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: findings from a literature review. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2016. Available at: http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review. Accessed March 22, 2017.

- 8.Ohio Colleges of Medicine Government Resource Center. The 2015 Ohio Medicaid Assessment Survey. Available at: http://grc.osu.edu/omas. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 9.Sommers A, Zuckerman S, Dubay L, Kenney G. Substitution of SCHIP for private coverage: results from a 2002 evaluation in ten states. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(2):529–537. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. June 30, 2015 effectuated enrollment snapshot. September 8, 2015. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-09-08.html. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 11.House Budget Committee Majority Staff. The War on Poverty: 50 years later. (pp109–110). Available at: http://budget.house.gov/uploadedfiles/war_on_poverty.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 12.Groves RM. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opin Q. 2006;70(5):646–675. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2015 Summary Data Quality Report. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2015/pdf/2015-sdqr.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 14.RTI Authors. 2015 Ohio Medicaid Assessment Survey Methodology Report. Available at: http://grc.osu.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/12015OMASMethReptFinal121115psg.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 15.CNN. Exit polls. 2016. Available at: http://www.cnn.com/election/results/exit-polls. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 16.Huang J, Jacoby S, Strickland M, Lai KK. Election 2016: exit polls. New York Times. November 8, 2016. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/11/08/us/politics/election-exit-polls.html?_r=0. Accessed February 6, 2017. [Google Scholar]