Abstract

State and local governments traditionally protect the health and safety of their populations more strenuously than does the federal government. Preemption, when a higher level of government restricts or withdraws the authority of a lower level of government to act on a particular issue, was historically used as a point of negotiation in the legislative process.

More recently, however, 3 new preemption-related issues have emerged that have direct implications for public health. First, multiple industries are working on a 50-state strategy to enact state laws preempting local regulation. Second, legislators supporting preemptive state legislation often do not support adopting meaningful state health protections and enact preemptive legislation to weaken protections or halt progress. Third, states have begun adopting enhanced punishments for localities and individual local officials for acting outside the confines of preemption.

These actions have direct implications for health and cover such topics as increased minimum wages, paid family and sick leave, firearm safety, and nutrition policies. Stakeholders across public health fields and disciplines should join together in advocacy, action, research, and education to support and maintain local public health infrastructures and protections.

Over the past several years, there has been a dramatic increase in the number and variety of preemptive bills and amendments proposed in states across the country. Preemption occurs when a higher level of government restricts or withdraws the authority of a lower level of government to act on a particular issue. Preemption is of particular concern in the area of public health, wherein state and local governments have historically protected the health and safety of their populations more vigorously than has the federal government.1 Furthermore, local successes often spur state and national action, as was the case with local smoke-free and menu-labeling laws.

The federal government’s authority to preempt state and local law derives from the Supremacy Clause of the US Constitution. In certain cases, the federal government enacts minimum standards and allows states and localities to build upon these protections, such as the nutrition guidelines under the National School Lunch Program. This aligns with the National Academy of Medicine recommendation that federal and state legislators “avoid framing preemptive legislation in a way that hinders public health action.”2 States, however, more routinely enact preemptive laws without such protections. State authority to preempt local law is rooted in each state’s constitution and statutes, which establish the local governments themselves and delineate the boundaries of local control. The majority of states retain the center of control at the state legislature.

Historically, preemption was used as a point of negotiation in the legislative process. Supporters of business interests would agree to health and safety protections in exchange for preemption because it is easier to negotiate and comply with 1 federal or state standard rather than contending and complying with local standards across thousands of jurisdictions. In the 1980s and 1990s, the tobacco, firearm, and alcohol industries shifted their focus from using preemption as a negotiating tool to making it their priority with respect to the establishment of state policies.3 As a result, for example, 43 states have varying degrees of comprehensive preemption of local firearm safety laws.4

More recently, however, 3 new preemption-related issues have emerged that have direct implications for health. First, multiple industries are working in concert on a 50-state strategy to preempt local regulation.5 Second, legislators supporting preemptive legislation often do not support the adoption of meaningful state health protections and enact preemptive legislation to weaken protections or halt progress. Third, states have begun adopting enhanced punishments for localities and individual local officials for acting outside the confines of preemption.

Here we provide 3 brief examples of preemptive legislation recently enacted by state governments, discuss potential health ramifications in these contexts, and explain a radical new method to punish municipalities for exercising their traditional authority to protect public health and safety. We conclude by highlighting the need for concerted action to counteract this trend.

RECENT PREEMPTIVE LEGISLATION

States have begun to preempt local action as the sole purpose of the law on a wide array of topics with direct ramifications for public health, such as increased minimum wages, paid family leave, firearm safety, fracking, and fire sprinklers.5

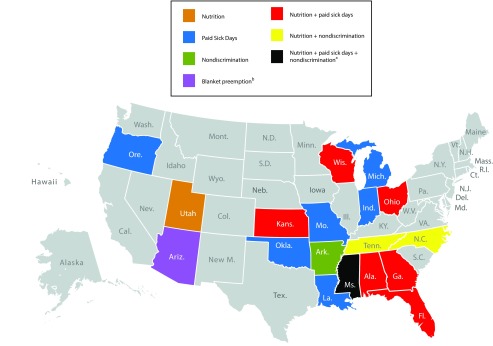

As of February 2017, 16 states preempt the ability of local jurisdictions to mandate earned sick days or other employee benefits (Figure 1). Michigan, for example, does not require employers to provide paid sick days to employees. In 2015, the state broadly prohibited local governments from adopting or enforcing any paid or unpaid family or sick leave policy.6 Paid sick day policies, specifically, allow workers to obtain medical care for themselves or their family through primary care settings, reduce the use of emergency rooms, and help prevent the spread of contagious illnesses.7 Those without paid sick days often forgo medical care for themselves and their family, with the highest risk found among the lowest-income workers.7

FIGURE 1—

State Preemption of Local Paid Sick Days and Nutrition and Nondiscrimination Laws: United States, February 2017

aMississippi adopted legislation in 2016 that grants special rights to citizens who hold 1 of 3 sincerely held religious beliefs or moral convictions reflecting disapproval of lesbian, gay, transgender, and unmarried persons. A Mississippi district court found the law to be unconstitutional and the case is on appeal to the 5th Circuit. If this law is upheld, inconsistent local ordinances protecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning persons from discrimination would be preempted.

bArizona has a form of “blanket” preemption. By notifying the state attorney general, a single legislator can freeze the transfer of state revenue-sharing funds to localities that adopt laws that “violate state law or the state constitution.” Arizona has also adopted individual laws preempting local paid sick days and nutrition ordinances.

Nine states preempt municipalities’ ability to regulate food establishments and operations, and these preemptive statutes have become increasingly broad. In a 2016 statute, Kansas preempted local regulation of—and expressly stated that the state would not regulate—food nutrition information, consumer incentive items, food-based health disparities, the growing and raising of livestock or crops, and the sale of foods or beverages.8 Local governments have led the country in innovative food policies such as requiring sodium warning labels on menus, restricting the sale of energy drinks to minors, and conditioning grocery store licenses on provision of fruits and vegetables. Municipalities in states such as Kansas are now unable to enact similar policies or address a primary cause of chronic disease—poor diets—as it relates to known disparities based on race, ethnicity, education, and income.9

The third example stems from the lack of equal protection afforded to LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) people under federal law. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (78 Stat 241) prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, gender, or national origin. State and local governments are free to enact their own stronger civil rights laws.

When communities in Arkansas began considering a law extending protections to members of sexual minority groups, the state preempted local governments from adopting or enforcing any policy creating a protected classification or prohibiting discrimination beyond state protections (which are lacking for LGBTQ individuals). The legislature characterized its preemption provision as an “emergency,” stating that uniformity was “immediately necessary” to preserve the “public peace, health, and safety.”10 However, the opposite is true. LGBTQ people are now the leading targets of hate crimes, and, in states that lack legal protection, LGBTQ individuals are at significantly increased risk of stress, mental health disturbances, risk-taking behavior, and substance use.11

In addition to enacting widespread preemption, one state adopted, and several have proposed, a radical strategy to quell local attempts at policymaking by punishing conflicts with state law. A 2016 Arizona law provides that any member of the state legislature may request the state attorney general to investigate local policies that might conflict with state law.12 Upon notice to the attorney general, the state will withhold funds owed to that municipality. Should the attorney general find a conflict, the municipality will permanently lose those funds, which will be redistributed.

Tucson, Arizona, is the subject of the first such action for destroying handguns seized in criminal investigations, a threat that comes with the potential permanent loss of $170 million a year in state aid for essential services such as fire, police, and public health services. Even if the attorney general or a court eventually finds that there is no conflict, the short-term revenue loss and fear of permanent loss have an enormous chilling effect on policymaking—de facto preemption—with severe consequences for communities. The withholding of state funds for public agencies and basic health and safety services poses an additional threat to public health.

CONCLUSIONS

Many state legislatures have enacted or are considering legislation with the potential to reverse years of public health progress and halt local leadership and innovation for years to come. Municipalities around the country are increasingly unable to address acute public health issues that will have lasting consequences for the health of communities. With the new federal administration, concerns now exist that state legislation will be preempted by federal law, leaving a potential gap in public health regulation on a national level. Stakeholders across public health fields and disciplines should join together in advocacy, action, research, and education to support and maintain local public health infrastructures and protections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Bare of Preemption Watch, a project of Grassroots Change, for his outstanding research assistance.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was needed for this study because no human participants were involved.

REFERENCES

- 1.Obama B. Presidential memorandum regarding preemption. Available at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/presidential-memorandum-regarding-preemption. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 2.National Academy of Sciences. For the public’s health: revitalizing law and policy to meet new challenges (report brief) Available at: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/For-the-Publics-Health-Revitalizing-Law-and-Policy-to-Meet-New-Challenges/Report-Brief.aspx. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 3.Gorovitz E, Mosher J, Pertschuk M. Preemption or prevention? Lessons from efforts to control firearms, alcohol, and tobacco. J Public Health Policy. 1998;19(1):36–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grassroots Change Preemption map: guns. Available at: http://grassrootschange.net/preemption-map/#/category/guns. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 5.Bottari M. The ALEC-backed war on local democracy. Available at: http://www.prwatch.org/news/2015/03/12782/alec-backed-war-local-democracy. Accessed March 8, 2017.

- 6.Michigan HB 4052 (2015).

- 7.Cook WK. Paid sick days and health care use: an analysis of the 2007 National Health Interview Survey data. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54(10):771–779. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kansas SB 366 (2016).

- 9.Rehm CD, Peñalvo JL, Afshin A, Mozaffarian D. Dietary intake among US adults, 1999–2012. JAMA. 2016;315(23):2542–2553. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arkansas Act 137 (2015).

- 11.Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: a prospective study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):452–459. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arizona SB 1487 (2016).