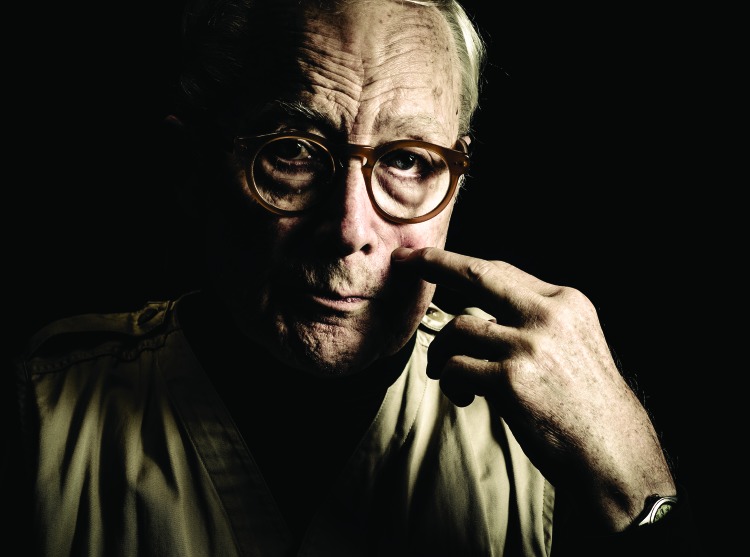

Professional photographer Damari McBride captured a portrait of each participant for the “Typical Day” project Web site and traveling exhibit, which also includes participants’ own photographs and stories. The Web site MyTypicalDay.org offers a platform for awareness, education, and storytelling for people affected by cognitive impairment. Photo by Damari McBride. Printed with permission.

For years Bob worried something was wrong with his memory. He expressed this worry to his family physician, who told him memory loss is a normal part of aging. “All these years that I’ve known that something was going on in my brain, I can see a curve,” said Bob. “It’s always been a pretty steady curve going slowly downhill.”

Bob’s steady decline was not just normal aging. It was a symptom of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a diagnosis characterized by measurable deficits in cognition that, although challenging, do not cause disability. For some patients, MCI may be the earliest sign of Alzheimer’s disease, and patients with MCI may eventually develop dementia.1 Along with 11 other MCI patients from the University of Pennsylvania’s Memory Center, Bob participated in a 2015 photo-elicitation project, for which patients were given cameras and asked to photograph images of a “typical day” living with MCI.2

Participants then discussed with our team the aspects of their everyday life that frustrate, facilitate, or challenge their memory. The participants, and sometimes their caregivers, welcomed the photo project as an opportunity to discuss how MCI has changed their lives, influencing their most intimate relationships, their daily social interactions, their ways of coping with everyday stressors, and, ultimately, their sense of self and what they value most in their lives.

Patients’ photographs served to expand the conversation between patients and our team at the Penn Memory Center, offering insight into patients’ lives outside the walls of the clinic.3 Those conversations allowed clinicians and research staff to further evaluate patients’ functional status, creating opportunities for support regarding how best to handle the “new normal” of lives lived with MCI. Often, participants offered profound commentary about the challenges of being patients—of relying increasingly on clinicians, family members, and friends for assistance in navigating quotidian demands once handled without conscious thought or effort. The patients’ stories and photographs captured elements of both loss and resilience.

Participants welcomed the opportunity to document their daily lives and share their stories, with the goal of raising awareness about cognitive impairment and reassuring people recently diagnosed. Bob captured a picture of his wife, also his caregiver, to discuss how his diagnosis affects not only him, but also the people around him. Photo by Bob. Printed with permission.

In Bob’s interview, he was surprisingly frank about what lies ahead for him. “There is steady deterioration,” he said. “I know where this goes.” But his wife has been more reluctant. “I think it probably embarrassed her,” he said. “She has slowly changed on that; I think we’re at a point now where she accepts that diagnosis.” This social embarrassment was not uncommon among project participants and their family members.

For Bob, as for all Typical Day project participants, interpersonal relationships—especially those with close family—were both centrally important and challenging. Many participants described the difficulty of negotiating a balance between sustained independence and reliance on caregivers, whose assistance was routinely needed in social situations that once had been easily managed. One of Bob’s images showed the steps leading to his front door. He explained:

Let’s say we’re going to go to a cocktail party. I worry about that because I walk into a room where I should know most of the people there. I’ve known them for years, and I’m at a point now where I will not be able to remember hardly any of the names. . . . It can be very embarrassing. But that’s just one example. There are plenty of other situations where I realize I’m going to go there with some trepidation.

The wife of another project participant expressed how her spouse had been “a very outgoing, gregarious person who was able to interact in groups or one on one, but he is not able to do that anymore,” and added, “I often have to remind him how to behave in social situations. It’s been very difficult for me.” These social challenges can both burden caregivers and contribute to stigma, shame, and social isolation for people experiencing MCI.

Caregivers played a critically important role in facing other social challenges, including medical appointments. Several participants said their loved ones offered valuable assistance by translating health care providers’ instructions. In addition, patients with MCI expressed worry about their own decision-making capacity and explained how they rely on caregivers for reassurance and decision support. Nonetheless, multiple project participants, including Bob, emphasized aspects of life that remain rewarding and largely unaffected by MCI, such as spending time with grandchildren. Most importantly, when participants with MCI talked about their caregivers, the overwhelming theme was the importance of the social support provided by their loved ones, especially in difficult times.

These patient narratives can serve as a valuable clinical tool for the health care team, helping them make accurate diagnoses, create plans for their patients’ futures, and guide caregivers in self-care strategies. After all, as another participant shared, the company of family and loved ones is “the best medicine out there.”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by the University of Pennsylvania’s National Institute on Aging funded Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center (P30-AG-010124), the Healthy Brain Research Network (U48-DP-005053), a Penn Medicine CAREs grant, and the Penn Neurosciences Department, University of Pennsylvania Health System.

The authors would like to thank the participants for sharing their stories and photographer Damari McBride for his work on this project.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The University of Pennsylvania institutional review board reviewed this study, which was classified as exempt.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roberts R, Knopman DS. Classification and epidemiology of MCI. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(4):753–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bugos E, Frasso R, FitzGerald E, True G, Adachi-Mejia AM, Cannuscio C. Practical guidance and ethical considerations for studies using photo-elicitation interviews. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E189. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlawish J. An Alzheimer’s doctor reveals his most powerful technology. August 5, 2016. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jasonkarlawish/2016/08/05/an-alzheimers-doctor-reveals-his-most-powerful-technology/#48a8f8687551. Accessed April 5, 2017.