Abstract

Objective(s):

Despite the good results of anticancer activities by curcumin, there are some hurdles that limit the use of curcumin as an anticancer agent. Many methods were examined to overcome this defect like the use of the dendrosomal curcumin (DNC). There is increasing evidence that miRNAs play important roles in biological processes. In this study, we focus on the roles of microRNA-21 in the anti-cancer effects of DNC in breast cancer.

Materials and Methods:

Also, we have used different methods such as MTT, apoptosis, cell cycle analysis, transwell migration assay and RT-PCR to find out more.

Results:

We observed that miR-21 decreased apoptotic cells in both cells (from 6.35% to 0.34 % and from 7.72% to 1.32% orderly) and DNC increased it. As well as, our findings indicated that cell migration capacity was increased by miR-21 over expression and was decreased by DNC. The combination of miR-21 vector transfection and DNC treatment showed lower percentage of apoptotic cells or a higher level of penetration through the membrane compared with DNC treatment alone. Furthermore, DNC induced a marked increase in the number of cells in sub G1/G1 phase and a decrease in G2/M phase of the cell cycle in both; but, we observed reverse results compared it, after transfection with miR-21 vector.

Conclusion:

We observed that miR-21 suppress many aspects of anti-cancer effects of DNC in breast cancer cells, it seems that co-treatment with DNC and mir-21 down-regulation may provide a clinically useful tool for drug-resistance breast cancer cells.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Cell cycle, Cell proliferation, Curcumin, Dendrosomal curcumin, MicroRNA-21

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common type of malignancy in women and the second leading cause of cancer-associated deaths worldwide, next to lung cancer and the incidence has been increasing for several decades. Although men can also get breast cancer, cases of male breast cancer account for less than .05% of all breast cancer cases diagnosed (1). Like most other malignant tumors, development, progression, invasion and metastasis of breast cancer are caused by multiple genetic alterations, which mechanism was not elucidated completely until now (2). In last few decades, researchers’ attention has focused mostly on the involvement of deregulated genes at the levels of DNA, protein, RNA, and microRNAs (miRNAs).

The discovery of miRNAs, which are endogenous, small (with ~22 nt length), non-protein-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by targeting mRNA transcripts for cleavage or translational repression, have provided new insights in cancer research. (3) There is increasing evidence that miRNAs play important roles in many biological processes, such as cell proliferation, invasion, migration, carcinogenesis, angiogenesis, differentia-tion and apoptosis (4). They act either as tumor suppressors or oncogenes, and alteration in their expression patterns has been linked to onset and progression of various cancers. Several other reports have described altered expression of miRNAs in cancer tissues compared to normal tissues, suggesting that these miRNAs could be potentially

represent novel clinical and prognostic biomarkers for the detection of various cancers (5, 6). Through the discovery of miRNAs and their different expression profiles among different kinds of diseases, the microRNA-21 (miR-21) was the common miRNA which could serve as a potential detection biomarker for digestive system cancer (7, 8). MiR-21 is one of the most frequently up-regulated miRs in many cancers including in breast cancer (9), hepatocellular carcinomas (10), gastric cancer (11), ovarian cancer (12, 13), cervical carcinoma (14), multiple head and neck cancer cell lines (15), papillary thyroid carcinoma (16), and prostate cancer (17) and some other solid tumors. As described above, miR-21 seems to play an important oncogenic role in malignant tumors. As to breast cancer, several studies have proved miR-21 was up-regulated in breast cancer both in vivo and in vitro by different kinds of method including Northern blotting (9), microarray (5, 9), bead-based flow cytometric miRNA expression profiling method (18), in situ hybridization (ISH) (19), bioluminescence-based hybridization assay (20) and real-time RT-PCR (21).

It is clear that systemic treatments for breast cancer such as chemotherapy or hormonal therapy have severe side effects (22). So, increasing focus on chemopreventive properties of natural compounds with plant-based formulations from traditional medicine has led to discovery of potential therapeutic agents targeting breast cancer and other cancers. In addition, plant-derived compounds (natural agents) could potentially regulate the expression of several miRNAs involved in cancer (23). Curcumin, (diferuloylmethane) an active component of the spice turmeric which extracted from the rhizome of Curcuma longa has promising potential in cancer prevention and therapy by interacting with proteins and modifying their expression and activity, which includes transcription factors, inflammatory cytokines, and factors of cell survival, proliferation, and angiogenesis and multiple signaling pathways (24). It is also noteworthy that, in recent studies have been observed curcumin have no toxicity even at high doses on clinical trials and is safe enough for human applications. (25, 26). Despite the good results of anticancer activities by curcumin, there are some hurdles such as low bioavailability, low stability in aqueous solutions, low absorption etc., as a result, these defects reduce anticancer applications of that. In order to achieve a particular aim, several strategies are required to overcome these caveats including chemical modifica-tion, metabolic blockers, artificial analogues of curcumin and several generations of liposomal structures, delivery by nanocarriers, amongst others (27). Consequently, many methods were examined to overcome this defect like the use of the dendrosomal curcumin (DNC) nanoparticles (28, 29). Our research group previous studies demonstrated the new light on the potential biocompatibility, the biodegradability and the anticancer and anti-metastatic effects of DNC nanoparticles in the biological systems (28-32). Also, accumulating lines of evidence have revealed that mir-21 can be regulated by curcumin and other herbal drugs (33). For example, curcumin has been found to decreases miR-21 levels in colorectal cancer (34), lung cancer (35), and pancreatic cancer (36). In this study, we sought to understand the roles of microRNA-21, as an intermediary agent in regulation of DNC nanoparticles anti-cancer functions in breast cancer. We used a dendrosomal carrier designed in our lab and curcumin for production DNC nanoparticles (37). This study evaluates DNC nanoparticles effects on mir-21 expression in three main cancerous cell lines of breast cancer: SKBR3, MDA-mb231, and MCF-7. Furthermore we investigate the anti-metastasis, cell cycle and cell growth inhibition, and apoptotic activation effect of DNC nanoparticles by simultaneously overexpression of miR -21 and DNC nanoparticles treatment. The results indicated cell proliferation inhibition by DNC nanoparticles treatment in comparison with free curcumin treatment was very much and miR-21 expression was significantly decreased dose-dependently after treatment by DNC nanoparticles in breast cancer cells. Also, miR-21 overexpression arrested anti cell proliferation, anti-metastasis and apoptotic activating effects of DNC nanoparticles in breast cancer cells. As well as, the results showed antagonistic effects of miR-21 re-expression and DNC nanoparticles on cell cycle analysis in breast cancer cells. Therefore, DNC nanoparticles as a miR-21 inhibitor might be effective in the treatment of breast malignancies.

Materials and Methods

Cells and reagents

Cells that were examined in this study (MCF7, SKBR3 and MDA-MB231 cell lines) were purchased from Pasteur Institute of Iran. The cells cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% of the antibiotics penicillin and streptomycin - incubation at 5% CO2 at 37 °C respectively. Curcumin was bought from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) with a purity of 95%. The Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics (University of Tehran, Iran) donated dendrosomal nanoparticles (Den 400), a biodegradable polyester. Method of dendrosome making, physical characteristics such as superficial charge, size, and also the rate of drug loading previously demonstrated (28, 30, 31, 37). Briefly, the OA400 carrier was synthesized by esterification of oleoyl chloride (0.01 mol) and polyethylene glycol 400 (0.01 mol) in the presence of triethyl amine (0.012 mol) and chloroform as the solvent at 25 °C for 4 hr. Triethylamine hydrochloride salt was filtered from its organic phase. Then, chloroform was evaporated from OA400 in vacuum oven at 40°C for 4 hr. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Spectrum One, PerkinElmer, Inc., Shelton, CT, USA) analysis was performed to confirm the dendrosomal chemical structure.

The mean diameter of DNC using distributed algorithm analysis of DLS, 200 nm was measured. A suitable value that does not show high stability around −7 mV, was calculated for the ζ-potential. The efficiency of curcumin loading was very much (87%) as well as, transmission electron micrographs results indicated DNC were spherical.

Preparation of dendrosomal curcumin (DNC) nano-particles

To provide DNC nanoparticles, we used optimized manufacturing methods of our laboratory (31). In summary, we investigated dendrosome/curcumin concentration range (about 1:50 to 1:10) by spectrophotometry in order to select the proper ratio and ultimately weight ratio of 1:25 was chosen as the optimum ratio. Dendrosome nanoparticles loaded with curcumin molecules using protocols MaLing Gou et al (37). DNC nanoparticles is prepared at a concentration of 2700 mM and conditions were kept away from light and in 4 ° C. DNC nanoparticles dilution before use in any method was performed using the culture medium (38).

MTT (Microculture Tetrazolium) assay

To check the inhibitory effect of DNC nanoparticles, free curcumin and dendrosome on viability of MCF7, SKBR3 and MDA-MB231 cells, MTT test was used; Thus, the cells plates in 96-well plates (5×103 cells & 100 µl PRMI per each wells) and then, each well treated with varying concentrations (0 to 30 μM) of the DNC nanoparticles, free curcumin and dendrosome for 48 hr. Previous research has shown that curcumin inhibits rate of human breast cancer cells growth, the nearly 100% after treatment with concentrations close to 30-40 μM. For this reason, in this study above mentioned concentrations was used in MTT test and for other tests, lower dosages of the DNC nanoparticles (≤ IC50 or some more) to minimize its anti-proliferative inhibition of cell migration. After 48 hr of incubation, 20 ml of MTT solution was added to each well (0.5 mg/ ml). Then, after 4 hr, the cells are carefully emptied and 200 microliters of DMSO was added to each well to completely dissolve precipitated insoluble formazan salt. The results were obtained by ELISA reader at wavelength of 570 nm.

MiR-21 tranfection

For the mir-21 overexpression experiment, MCF7 and MDA-MB231 cells were seeded in six-well plates in complete RPMI-1640 medium for 24 hr, washed twice with RPMI-1640 medium (without serum), and transiently transfected with miR-21 overexpressing vector or scramble (vector with scramble sequence as an insert) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. All transfections were done 24 hr before the addition of DNC nanoparticles. Then the cells under different treatments, were incubated for 48 hr as shown in the results section, the test outputs were analyzed and assessed. MiR-21 overexpressing vector was a gift from Dr Seyad Javad Mowla, genetics group, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, iran.

Transwell migration assay

In this test, transwell membranes (8 μm pore size, 6.5mm diameter) were coated with diluted fibronectin in serum-free RPMI medium (2.5mg/ml). After that, the cells (5×105) were trypsinized, washed, and maintained in a medium lacking FBS. Upper level of the transwells (24-wells plate) loaded with serum-free medium & cells and in lower level, into the wells were added migration-inducing medium (with 10% FBS) then, they contained different treatments (negative control, scramble trans-fection, mir-21 overexpressing vector transfection, DNC nanoparticles (IC50 concentration) and cotreatment of mir-21 transfection and DNC nanoparticles. The transwells were separated and depleted after 8 hr incubation. After that, membranes were fixed with methanol and wiped on the cells of the upper side. With using 20% Giemsa solution were stained membranes. The migrated cells to the lower surface were counted by the light microscope (39). The following equation was used for calculating of Metastasis Index:

Metastasis Index= Mean of migrated cells in each treatment/Mean of migrated cells in negative control. The metastasis index in negative control was 1.

Cell apoptosis assay

With using Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit, cell apoptosis was analysed. The MCF7 and MDA-MB231 cells were plated in 6-well plates 24 hr and after that, treated with mir-21 overexpressing vector transfection, DNC nanoparticles (IC50 concentration) and cotreatment of both of them for 48 hr. The rest of the process was carried out in the same way that the manufacturer’s instructions had mentioned. Finally, with using flow cytometer, Annexin V and PI were analyzed (40).

Cell cycle analysis

The effect of DNC nanoparticles treatment and mir-21 overexpressing vector transfection or both of them on the distribution of cells in cell cycle was performed by flow cytometry analysis using propidium iodide (PI) staining. The MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 12-well plate (5×105 cells/ml) and treated with mir-21 vector transfection, DNC nanoparticles (IC50 concentration

and cotreatment of both of them for 48 hr. The cells were then harvested and rinsed with cold PBS, fixated in cold 75% ethanol for 15 min at 4 °C. The cells were plated in PBS containing 50 µg/ml PI, 0.1% sodium citrate, and 0.1 Triton X-100 followed by shaking at 37 °C for 15 min. Analyses were done on a FACS flow cytometer.

Mir-21 expression analysis by real-time PCR

After treatment of cells for 48 hr with mir-21 transfection, DNC nanoparticles (IC50 concentration) and cotreatment of both of them, RNA was drew out from MCF7 and MDA-MB231 cells with Trizol based on the principles mentioned in the instructions. Expression of mature miRNAs was assayed using stem-loop RT followed by real time PCR analysis, as previously described (41). With using a RevertAid Reverese transcriptase cDNA Synthesis Kit, cDNA was synthesized and kept at −20 °C until use. With using a light cycler instrument & 5x HOT FIREPol® EvaGreen® HRM Mix (ROX), real-time PCR was done. PCR products were analysed by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis. The relative amount of each miRNA was normalised to an individual U6 snRNA molecule. The fold-change for each miRNA in DNC nanoparticles -treated cells relative to control (untreated) cells was calculated using the Ct (2-ΔΔCt) method (42), where ΔΔCt=ΔCt DNC nanoparticles treated - ΔCt untreated and ΔCt = Ct miRNA-Ct U6. PCR was performed in triplicate. In Table 1 the primers used for stem-loop RT- PCR for miR-21 have been listed.

Table 1.

| Gene | Accession number | Forward primer (5’–3’) | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem-loop RT primer for miR-21 | NR_029493.1 | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTTTCGCACTGGATACGACTCAACA | 49 |

| Forward primer for miR-21 | CCGGCCTAGCTTATCAGACTG | 21 | |

| Reverse primer for miR-21 | AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTA | 18 | |

| Forward primer for 5SRNA | NR_023363.1 | TCTACGGCCATACCACCCT | 19 |

| Reverse or RT primer for 5SRNA | GCCTACAGCACCCGGTATT | 19 |

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean±SD. All tests were repeated for 3 times. In this research, statistical significances were computed using one-way variance analysis and a Student’s t-test. <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

DNC nanoparticles stops cell growth of breast cancer cells

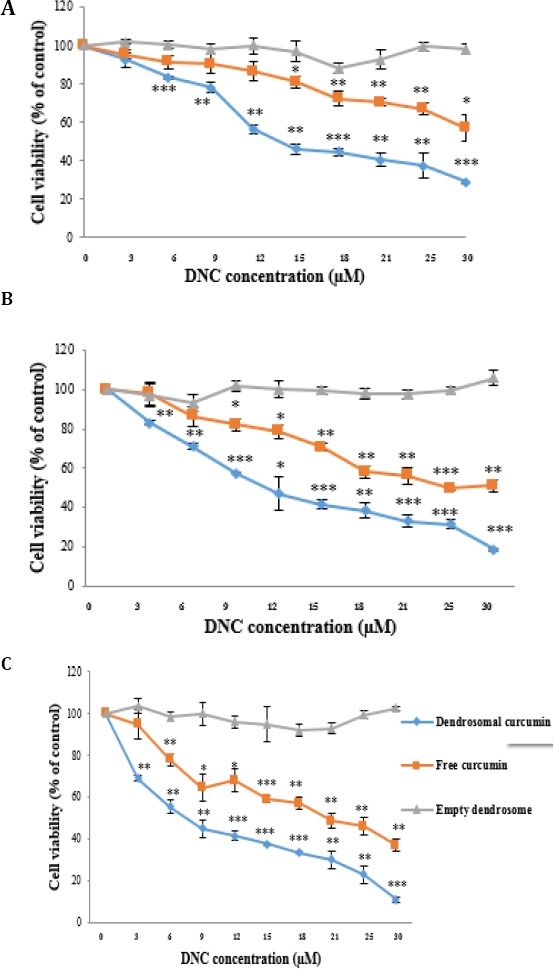

First, we perform MTT assay in 48 hr to assess DNC, free curcumin and dendrosome treatment effects on cell viability of MCF7, MDA-MB231 and SKBR3 cells. Our results showed treatment of DNC nanoparticles and free curcumin inhibited cell growth dose dependently in all above mentioned cells (Figure 1A, B and C). However, the cell survival of MCF7, MDA-MB231 and SKBR3 cells was not affected very much (more than 30%) by free curcumin only for SKBR3 cells (from 13 -30 µM) and for MDA-MB231 cells (from 15-30 µM). But, cell proliferation rate inhibition by DNC treatment in comparison with free curcumin treatment was a little more. In order to evaluate the performance of DNC nanoparticles on MCF7, MDA-MB231 and SKBR3 cells, we compared the IC50 of DNC nanoparticles in these cells. Cell sensitivity to DNC nanoparticles was greatly more for SKBR3 in comparison to MDA-MB231 and MCF7 cells as characterized by a lower IC50 for SKBR3 rather than MDA-MB231 and MCF7 in 48 hr orderly (from 8.31 to 11.66 and 13.45 µM). As expected, dendrosome alone had no effect on all cells. Overall, these findings suggest that dendrosome without any toxic effects enhances the solubility and absorption of Curcumin. As a result, we treated DNC nanoparticles instead of free curcumin in this study. To do that, a number of studies evaluated effects of curcumin in the time 48 hr and IC50 concentration in breast cancer cells, so this treatment time and dose was used in the subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Effects of DNC, free curcumin and dendrosome on cell viability. The cell line was treated with different concentrations of DNC, free curcumin and free dendrosome (0–30 µM) for 48 hrs (A) MCF7 (B) MDA-MB231(C) SKBR3 and their viability was assessed using MTT assay. Results are expressed as a percentage of viability compared to control and are presented as mean±SD from three independent experiments. Significance was set at * P\0.05, ** P\0.01, *** P\0.001

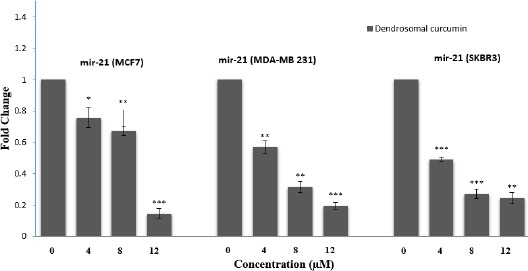

DNC nanoparticles decreased miR-21 expression in breast cancer cells

To evaluate whether treatment of DNC nanopar-ticles could adjust miR-21 expression in MCF7, MDA-MB231 and SKBR3 cells, real-time PCR assay was performed. Significantly expression of miR-21 was diminished after treatment of DNC nanoparticles 4, 8 and 12 µM dose dependently in all above mentioned cells (Figure 2). Next, we focus on the roles of microRNA-21 in the anti-cancer effects of DNC nanoparticles including the anti-metastasis, apoptosis activating, and cell cycle inhibition in MCF7 and MDA-MB231 cells as 2 candidate cells.

Figure 2.

Effect of DNC on transcriptional levels of miR-21 measured by real-time PCR. Data are shown as fold change in relative expression compared with SnU6 on the basis of Comparative Ct (2- Δ (ΔCt)) method. Data are presented as mean±SD from three independent experiments. Significance was set at * P\0.05, ** P\0.01, *** P\0.001

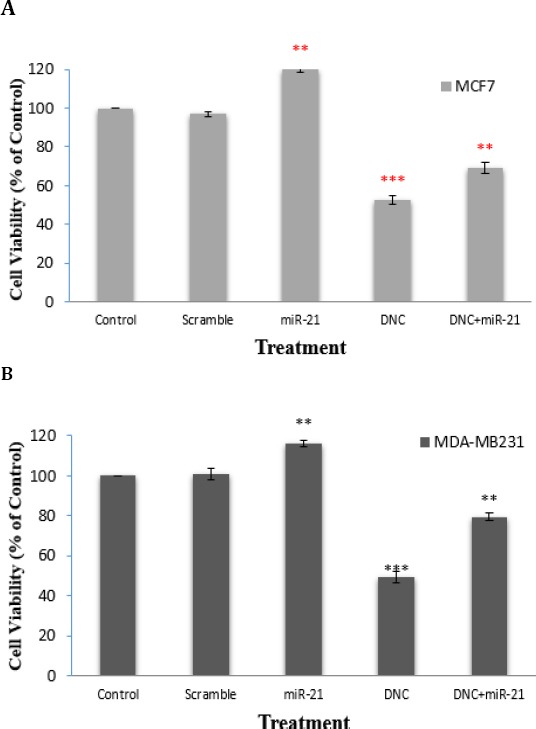

MiR-21 overexpression arrested anti cell proliferation effect of DNC nanoparticles in breast cancer cells

To evaluate miR-21 function on anti-cell growth effect of DNC nanoparticles, both MCF7 and MDA-MB231 cells were transfected with miR-21 overexpressing vector and after that MTT assay was done. Results showed that miR-21 re-expression increased and DNC nanoparticles treatment (in IC50 dose, 13.45 for MCF7 and 11.66 µM for MDA-MB231 cells) decreased cell proliferation in both cells (Figure 3A and B). Simultaneously, we found that miR-21 re-expression partly abrogated inhibition of cell amplification induced by DNC nanoparticles treatment. In other hands, the combination treatment of DNC nanoparticles and miR-21 re-expression exhibited obvious antagonistic anti-proliferative effect in both cells. Treatments with DNC nanoparticles resulted in maximal inhibition of 47.5% and 51% at 48 hr in MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 orderly, while co-delivery of miR-21 overexpressing vector and DNC nanoparticles, resulted in maximal inhibition of 31% and 20.5% during the observation time. These results indicated that re-expressing of miR-21 made the cells more resistant to DNC nanoparticles.

Figure 3.

Effect of MiR-21 overexpression on anti-cell proliferation effect of DNC in breast cancer cells. MTT assay was performed after DNC treatment (in IC50 dose, 13.45 and 11.66 µM for MCF7 and MDA-MB231, orderly) or miR-21 overexpressing vector transfection or the combination in MCF7 (A) and MDA-MB231 (B) cells. Scramble: vector with scramble sequence as an insert. Significance was set at * P\0.05, ** P\0.01, *** P\0.001

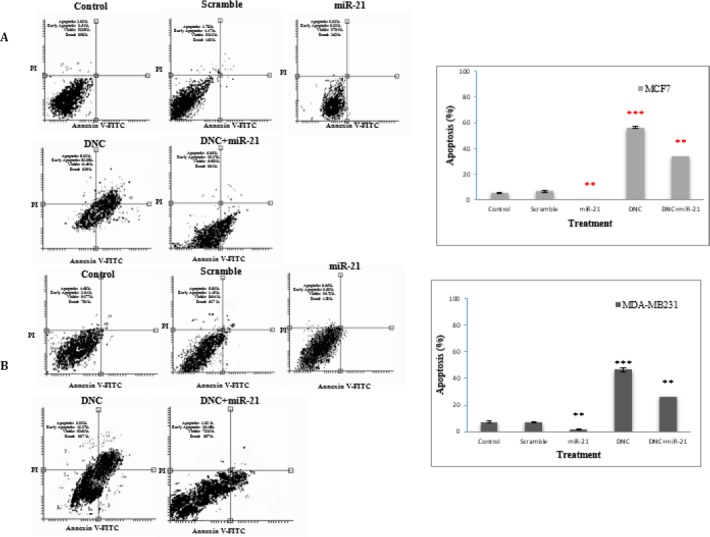

MiR-21 overexpression abrogated apoptotic activating effect of DNC in breast cancer cells

We evaluate whether miR-21 re-expression can inhibit apoptosis in MCF7 and MDA-MB231 cells. Our results showed that apoptotic cells percentage diminished after miR-21 re-expression in both cells (from 6.35% to 0.34% in MCF7 and from 7.72% to 1.32 % in MDA-MB231 cells). As we see in Figure 4A and B, the combination of miR-21 overexpressing vector transfection and DNC nanoparticles treatment (in IC50 dose, 13.45 for MCF7 and 11.66 µM for MDA-MB231 cells) showed lower percentage of apoptotic cells than DNC nanoparticles. The results offered that down-regulation of miR-21 in breast cancer cells by DNC nanoparticles is a main agent for its cell apoptosis inducing effect.

Figure 4.

Effect of MiR-21 overexpression on apoptosis activating effect of DNC in breast cancer cells. Apoptosis was detected by Annexin V-FITC/PI method in MCF7 (A) and MDA-MB231 (B) cells after DNC treatment (in IC50 dose, 13.45 and 11.66 µM for MCF7 and MDA-MB231, orderly) or miR-21 overexpressing vector transfection or the combination. Scramble: vector with scramble sequence as an insert. Significance was set at * P\0.05, ** P\0.01, *** P\0.001

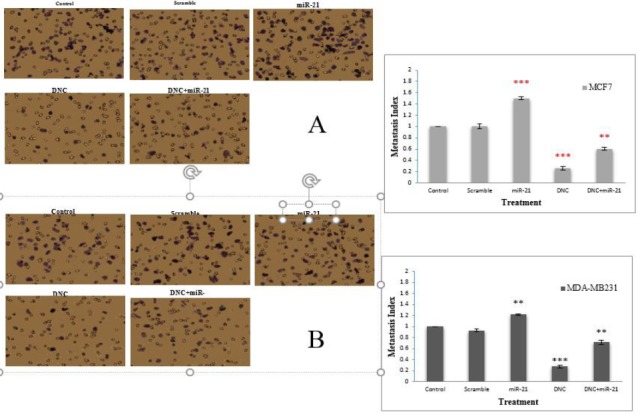

MiR-21 overexpression arrested anti-metastasis effect of DNC in breast cancer cells

To assess the miR-21 function in anti-metastasis capacity of DNC nanoparticles in both MCF7 and MDA-MB231 cells, Transwell assay was performed. The results showed that capacity of cell migration was enhanced by overexpression of miR-21 and was decreased by DNC nanoparticles treatment (in IC50 dose, 13.45 for MCF7 and 11.66 µM for MDA-MB231 cells) in both cells (Figure 5A and B). Notably, penetration through the membrane compared with treatment of DNC nanoparticles was lower for cotreatment of DNC nanoparticles with miR-21 overexpressing vector. In agreement with this observation, we showed that miR-21 overexpression arrested anti-metastasis effect of DNC nanoparticles in breast cancer cells to a certain degree.

Figure 5.

Effect of MiR-21 overexpression on anti-metastasis effect of DNC in breast cancer cell. Cell migration was measured using transwell inserts in MCF7 (A) and MDA-MB231 (B) cells after DNC treatment (in IC50 dose, 13.45 and 11.66 µM for MCF7 and MDA-MB231, orderly) or miR-21 overexpressing vector transfection or the combination. Scramble: vector with scramble sequence as an insert. Significance was set at * P\0.05, ** P\0.01, *** P\0.001

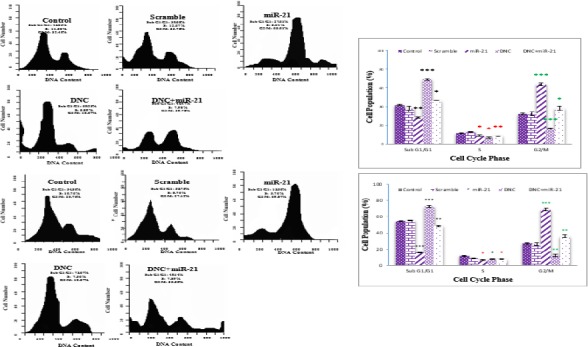

Antagonistic Effects of miR-21 re-expression and DNC on cell cycle analysis in breast cancer cells

To understand the antagonistic effects of miR-21 re-expression and DNC nanoparticles treatment on cell growth, we exposed MCF7 and MDA-MB231 cells to miR-21 overexpressing vector transfection and DNC nanoparticles treatment (in IC50 dose, 13.45 for MCF7 and 11.66 µM for MDA-MB231 cells) alone or in combination to evaluated changes in the cell cycle distribution after 48 hr. Uninfected and untreated cells served as a negative control. Free DNC nanoparticles induced a marked increase (P<0.001) in the number of cells in sub G1/G1 phase and a significant decrease (P<0.001) in the number of cells in G2/M phase of the cell cycle in both cells (Figure 6A and B); also, after transfection with miR-21 overexpressing vector alone was observed reverse results compared to DNC nanoparticles. Results of combination seemed to be able to achieve the antagonistic effects in both cells.

Figure 6.

Effect of MiR-21 overexpression and DNC on cell cycle progression in breast cancer cell. The distribution of cell cycle stages was analyzed by flow cytometry after 48 hr of treatment with miR-21 overexpressing vector and DNC (in IC50 dose, 13.45 and 11.66 µM for MCF7 and MDA-MB231, orderly) alone or in combination in MCF7 (A) and MDA-MB231 (B) cells. Histogram showing the percentage of cells in different phases of the cell cycle. Scramble: vector with scramble sequence as an insert. Significance was set at * P\0.05, ** P\0.01, *** P\0.001

Discussion

Cancer accounts for the leading cause of mortality in developed countries and the second highest in developing countries, making it a global health issue. It is immediate to diagnose cancer in the early stage by a noninvasive way. However, few molecules have been detected as biomarkers for therapy or diagnosis in clinical application. Therefore, it was significant to search novel biomarkers using a less invasive method. MicroRNAs are non-coding RNA molecules that post-transcriptionally regulate expression of target genes and have been implicated in the progress of cancer proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. MiRNAs are now recognized as key players of post-transcriptional control of gene expression. It has been shown that alterations of some miRNAs expression may play a role in the development of human cancers (43). While many miRNA are down-regulated or deleted in cancers including let-7, miR-15 and miR-16 (33, 44), oncogenic miRNAs are frequently overexpressed in very diverse types of malignancy, particularly, miR-21 is overexpressed in most tumors. Several evidences have shown that the inhibitory effects of curcumin on cancer development is done in part through regulation of miRNA (45). It is proven that, curcumin up-regulates miR-9 in ovarian cancer cells and by that modulates Akt/FOXO1 axis (35). In addition, curcumin through miR-186 down-regulation activated apoptosis in lung adenocarcinoma cells (46). Likewise, curcumin has been found to inhibit migration by controlling miR-181b expression in breast cancer (47). Curcumin also regulated the Src-Akt expression axis via modulating miR-203 level in bladder cancer (48). Different researches have proved that curcumin controled many miRNAs alike miR-200 (49, 50), miR-34 (51), miR-19 (52), and miR-7 (9). MicroRNA-21 (miR-21), a small noncoding RNA with 23 nucleotides that regulates several apoptotic and tumor suppressor genes and contributes to the initiation, promotion, and progression of tumors is a key microRNA that is overexpressed in most human cancers, including breast cancer. MiR-21 shows a critical oncogenic role in malignant tumors and especially in breast cancer. Several studies have suggested that miR-21 was up-regulated in breast cancer both in vivo and in vitro (18, 19). Interestingly, miR-21 was found to be significantly up-regulated in BC in miRNA expression profiles (5). It was recently reported that miR-21 mediates MCF-7 cell growth; suppression of this miRNA, which is also overexpressed in MCF-7 cells, was associated with increased apoptosis and decreased cell proliferation (20).

Curcumin has been revealed to reduce the miR-21 expression in various cancers (21). Mudduluru et al showed that curcumin inhibited colon cancer cell cycles through down-regulation of miR-21 (34). In another study, Zhang et al reported that curcumin decreased human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cell proliferation and increased apoptosis with decreased miR-21 (35). Bao et al demonstrated that curcumin analogue difluorinated curcumin (CDF) reduced pancreatic cancer cell migration via decreasing miR-21 (36). Curcumin can also cause anoikis, which refers to cell death after detachment (55, 56). In addition, Curcumin has been shown to decrease NF-κB via miR- 21 (57). It has also been found that curcumin decreases miR-21 by increasing its secretion carried in exosomes in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) cell lines K562 and LAMA84 (2). Similarly, curcumin was shown to inhibit activator protein-1 (AP-1) binding upstream of the pri-miR-21, which reduced miR-21 expression and induced expression of the tumor suppressor Pdcd4, a target of miR- 21 (35). The anticancer effects of DNC nanoparticles in the biological systems have been examined in our previous studies (28-31) In the present study for the first time, the mediating role of mir-21 in anti-cancer mechanisms of curcumin in breast cancer cells, were studied. At first, a series of quantitative analyses were carried out based on our findings and revealed that dendrosomal curcumin (DNC) nanoparticles could down-regulate miR-21 expression, induce apoptosis and inhibit metastasis, cell growth and cell cycle in breast cancer cells. Also, we demonstrated the antagonistic anticancer effects of the combination of dendrosomal curcumin (DNC) nanoparticles treatment and miR-21 overexpression to suppress the growth ability, metastasis, cell cycle and activation of apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Accordingly, 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of DNC nanoparticles were significantly increased to a greater extent in the cells transfected with miR-21 vector (overexpression). DNC treatment could increase the percentage of apoptotic breast cancer cells among miR-21-transfected cells compared with non-transfected cells. Furthermore, treatment of the miR-21-transfected cells with DNC nanoparticles resulted in significantly decreased cell viability and invasiveness compared with mock cells.

Conclusion

The results obtained in this study indicate that the oncogenic role of mir-21 is a main agent in the resistance of breast carcinoma cells to DNC. Since miR-21 suppress many aspects of anti-cancer effects of DNC including cell proliferation, cell cycle and metastasis inhibition and apoptotic activation in breast cancer cells, it seems that co-treatment with DNC and mir-21 down-regulation may provide a clinically useful tool for drug-resistance breast cancer cells.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to all of those who provided rich insights into the field. Also, we apologize to the colleagues whose work could not be cited due to space limitations. This work was supported from Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2012. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu C-G, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proceedings of the National academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattie MD, Benz CC, Bowers J, Sensinger K, Wong L, Scott GK, et al. Optimized high-throughput microRNA expression profiling provides novel biomarker assessment of clinical prostate and breast cancer biopsies. Molecular cancer. 2006;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yanaihara N, Caplen N, Bowman E, Seike M, Kumamoto K, Yi M, et al. Unique microRNA molecular profiles in lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer cell. 2006;9:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Gao X, Wei F, Zhang X, Yu J, Zhao H, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of circulating miR-21 for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gene. 2014;533:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu X, Lv M, Wang H, Guan W. Identification of circulating microRNAs as novel potential biomarkers for gastric cancer detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2014;59:911–919. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2970-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Liu C-G, Veronese A, Spizzo R, Sabbioni S, et al. MicroRNA gene expression deregulation in human breast cancer. Cancer research. 2005;65:7065–7070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kutay H, Bai S, Datta J, Motiwala T, Pogribny I, Frankel W, et al. Down-regulation of miR-122 in the rodent and human hepatocellular carcinomas. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2006;99:671–678. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Zhang Z, Li Z, Gao C, Chen P, Chen J, Liu W, et al. miR-21 plays a pivotal role in gastric cancer pathogenesis and progression. Laboratory investigation. 2008;88:1358–1366. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iorio MV, Visone R, Di Leva G, Donati V, Petrocca F, Casalini P, et al. MicroRNA signatures in human ovarian cancer. Cancer research. 2007;67:8699–8707. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nam EJ, Yoon H, Kim SW, Kim H, Kim YT, Kim JH, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles in serous ovarian carcinoma. Clinical cancer research. 2008;14:2690–2695. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lui W-O, Pourmand N, Patterson BK, Fire A. Patterns of known and novel small RNAs in human cervical cancer. Cancer research. 2007;67:6031–6043. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran N, McLean T, Zhang X, Zhao CJ, Thomson JM, O’Brien C, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles in head and neck cancer cell lines. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2007;358:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tetzlaff MT, Liu A, Xu X, Master SR, Baldwin DA, Tobias JW, et al. Differential expression of miRNAs in papillary thyroid carcinoma compared to multinodular goiter using formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissues. Endocrine pathology. 2007;18:163–173. doi: 10.1007/s12022-007-0023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasahara K, Taguchi T, Yamasaki I, Kamada M, Yuri K, Shuin T. Detection of genetic alterations in advanced prostate cancer by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer genetics and cytogenetics. 2002;137:59–63. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blenkiron C, Goldstein LD, Thorne NP, Spiteri I, Chin S-F, Dunning MJ, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling of human breast cancer identifies new markers of tumor subtype. Genome biology. 2007;8:1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sempere LF, Christensen M, Silahtaroglu A, Bak M, Heath CV, Schwartz G, et al. Altered MicroRNA expression confined to specific epithelial cell subpopulations in breast cancer. Cancer research. 2007;67:11612–11620. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cissell KA, Rahimi Y, Shrestha S, Hunt EA, Deo SK. Bioluminescence-based detection of microRNA, miR21 in breast cancer cells. Analytical chemistry. 2008;80:2319–2325. doi: 10.1021/ac702577a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Si M, Zhu S, Wu H, Lu Z, Wu F, Mo Y. miR-21-mediated tumor growth. Oncogene. 2007;26:2799–2803. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noh E-M, Yi MS, Youn HJ, Lee BK, Lee Y-R, Han J-H, et al. Silibinin enhances ultraviolet B-induced apoptosis in mcf-7 human breast cancer cells. Journal of breast cancer. 2011;14:8–13. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2011.14.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buhrmann C, Mobasheri A, Matis U, Shakibaei M. Curcumin mediated suppression of nuclear factor-κB promotes chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in a high-density co-culture microenvironment. Arthritis research & therapy. 2010;12:1. doi: 10.1186/ar3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunnumakkara AB, Anand P, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin inhibits proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis of different cancers through interaction with multiple cell signaling proteins. Cancer letters. 2008;269:199–225. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta SC, Patchva S, Koh W, Aggarwal BB. Discovery of curcumin, a component of golden spice, and its miraculous biological activities. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2012;39:283–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogel A, Pelletier J. Examen chimique de la racine de Curcuma. J Pharm. 1815;1:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masika J, Zhao Y, Hescheler J, Liang H. Modulation of miRNAs by Natural Agents: Nature’s way of dealing with cancer. RNA & DISEASE. 2015:3. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarbolouki MN, Sadeghizadeh M, Yaghoobi MM, Karami A, Lohrasbi T. Dendrosomes: a novel family of vehicles for transfection and therapy. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology. 2000;75:919–922. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alizadeh AM, Khaniki M, Azizian S, Mohaghgheghi MA, Sadeghizadeh M, Najafi F. Chemoprevention of azoxymethane-initiated colon cancer in rat by using a novel polymeric nanocarrier–curcumin. European journal of pharmacology. 2012;689:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babaei E, Sadeghizadeh M, Hassan ZM, Feizi MAH, Najafi F, Hashemi SM. Dendrosomal curcumin significantly suppresses cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. International immunopharmacology. 2012;12:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mirgani MT, Isacchi B, Sadeghizadeh M, Marra F, Bilia AR, Mowla SJ, et al. Dendrosomal curcumin nanoformulation downregulates pluripotency genes via miR-145 activation in U87MG glioblastoma cells. International journal of nanomedicine. 2014;9:403–417. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S48136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farhangi B, Alizadeh AM, Khodayari H, Khodayari S, Dehghan MJ, Khori V, et al. Protective effects of dendrosomal curcumin on an animal metastatic breast tumor. European journal of pharmacology. 2015;758:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sethi S, Li YH, Sarkar F. Regulating miRNA by natural agents as a new strategy for cancer treatment. Current drug targets. 2013;14:1167–1174. doi: 10.2174/13894501113149990189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mudduluru G, George-William JN, Muppala S, Asangani IA, Kumarswamy R, Nelson LD, et al. Curcumin regulates miR-21 expression and inhibits invasion and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Bioscience reports. 2011;31:185–197. doi: 10.1042/BSR20100065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang W, Bai W. MiR-21 suppresses the anticancer activities of curcumin by targeting PTEN gene in human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. Clinical and Translational Oncology. 2014;16:708–713. doi: 10.1007/s12094-013-1135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bao B, Ali S, Kong D, Sarkar SH, Wang Z, Banerjee S, et al. Anti-tumor activity of a novel compound-CDF is mediated by regulating miR-21, miR-200, and PTEN in pancreatic cancer. PloS one. 2011;6:e17850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 37.Gou M, Men K, Shi H, Xiang M, Zhang J, Song J, et al. Curcumin-loaded biodegradable polymeric micelles for colon cancer therapy in vitro and in vivo. Nanoscale. 2011;3:1558–1567. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00758g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Journal of immunological methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen H-C. Boyden chamber assay. Cell Migration: Developmental Methods and Protocols. 2005:15–22. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-860-9:015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lian J, Zhang X, Tian H, Liang N, Wang Y, Liang C, et al. Altered microRNA expression in patients with non-obstructive azoospermia. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2009;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song B, Wang C, Liu J, Wang X, Lv L, Wei L, et al. MicroRNA-21 regulates breast cancer invasion partly by targeting tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 expression. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;29:1. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer AJ, Zhou Z, Lee DH, Nguyen JT, et al. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem–loop RT–PCR. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:e179–e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E, et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro-RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao S-F, Zhang X, Zhang X-J, Shi X-Q, Yu Z-J, Kan Q-C. Induction of microRNA-9 mediates cytotoxicity of curcumin against SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP. 2013;15:3363–3368. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.8.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kronski E, Fiori ME, Barbieri O, Astigiano S, Mirisola V, Killian PH, et al. miR181b is induced by the chemopreventive polyphenol curcumin and inhibits breast cancer metastasis via down-regulation of the inflammatory cytokines CXCL1 and-2. Molecular oncology. 2014;8:581–595. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saini S, Arora S, Majid S, Shahryari V, Chen Y, Deng G, et al. Curcumin Modulates MicroRNA-203–Mediated Regulation of the Src-Akt Axis in Bladder Cancer. Cancer prevention research. 2011;4:1698–1709. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang H-H, Wei P-L, Hung C-S, Wu C-T, Wang W, Huang M-T, et al. MicroRNA-200a/b influenced the therapeutic effects of curcumin in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells. Tumor Biology. 2013;34:3209–3218. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0891-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reuter S, Gupta SC, Park B, Goel A, Aggarwal BB. Epigenetic changes induced by curcumin and other natural compounds. Genes & nutrition. 2011;6:93–108. doi: 10.1007/s12263-011-0222-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roy S, Levi E, Majumdar AP, Sarkar FH. Expression of miR-34 is lost in colon cancer which can be re-expressed by a novel agent CDF. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2012;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li X, Xie W, Xie C, Huang C, Zhu J, Liang Z, et al. Curcumin Modulates miR-19/PTEN/AKT/p53 Axis to Suppress Bisphenol A-induced MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation. Phytotherapy Research. 2014;28:1553–1560. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma J, Fang B, Zeng F, Pang H, Zhang J, Shi Y, et al. Curcumin inhibits cell growth and invasion through up-regulation of miR-7 in pancreatic cancer cells. Toxicology letters. 2014;231:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar S, Keerthana R, Pazhanimuthu A, Perumal P. Overexpression of circulating miRNA-21 and miRNA-146a in plasma samples of breast cancer patients. 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmittgen TD, Jiang J, Liu Q, Yang L. A high-throughput method to monitor the expression of microRNA precursors. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32:e43–e43. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chan JA, Krichevsky AM, Kosik KS. MicroRNA-21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer research. 2005;65:6029–6033. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ciafre S, Galardi S, Mangiola A, Ferracin M, Liu C-G, Sabatino G, et al. Extensive modulation of a set of microRNAs in primary glioblastoma. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2005;334:1351–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roldo C, Missiaglia E, Hagan JP, Falconi M, Capelli P, Bersani S, et al. MicroRNA expression abnormalities in pancreatic endocrine and acinar tumors are associated with distinctive pathologic features and clinical behavior. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:4677–4684. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.5194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]