Abstract

Small-molecule inhibitors of the CDK4/6 cell-cycle kinases have shown clinical efficacy in estrogen receptor (ER)-positive metastatic breast cancer, although their cytostatic effects are limited by primary and acquired resistance. Here we report that ER-positive breast cancer cells can adapt quickly to CDK4/6 inhibition and evade cytostasis, in part, via noncanonical cyclin D1-CDK2–mediated S-phase entry. This adaptation was prevented by cotreatment with hormone therapies or PI3K inhibitors, which reduced the levels of cyclin D1 (CCND1) and other G1–S cyclins, abolished pRb phosphorylation, and inhibited activation of S-phase transcriptional programs. Combined targeting of both CDK4/6 and PI3K triggered cancer cell apoptosis in vitro and in patient-derived tumor xenograft (PDX) models, resulting in tumor regression and improved disease control. Furthermore, a triple combination of endocrine therapy, CDK4/6, and PI3K inhibition was more effective than paired combinations, provoking rapid tumor regressions in a PDX model. Mechanistic investigations showed that acquired resistance to CDK4/6 inhibition resulted from bypass of cyclin D1–CDK4/6 dependency through selection of CCNE1 amplification or RB1 loss. Notably, although PI3K inhibitors could prevent resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors, they failed to resensitize cells once resistance had been acquired. However, we found that cells acquiring resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors due to CCNE1 amplification could be resensitized by targeting CDK2. Overall, our results illustrate convergent mechanisms of early adaptation and acquired resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors that enable alternate means of S-phase entry, highlighting strategies to prevent the acquisition of therapeutic resistance to these agents.

Introduction

Substantial improvements have been made in the treatment of estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer, targeting the ER with antiestrogen hormonal therapies or through estrogen withdrawal by aromatase inhibitors. However, resistance to hormonal therapies is inevitable in metastatic breast cancer, and frequent in early breast cancer (1). A common feature of ER-positive breast cancer is high expression of cyclin D1 (CCND1; refs. 2–4). In mouse models of ER-positive breast cancer, cyclin D1 is required for oncogenesis (5). Cyclin D1 through CDK4 and CDK6, initiates cell-cycle entry by phosphorylating and inactivating the retinoblastoma protein (pRb) that uncouples from E2F transcription factors (6). The release of E2F transcription factors initiates an S-phase transcriptional program promoting E-type cyclin and CDK2 expression and cell-cycle progression (7).

Inhibition of CDK4/6 with small-molecule inhibitors such as palbociclib (PD0332991), abemacilib (LY2835219; ref. 8), and ribociclib (LEE011; ref. 9) has shown substantial promise in early-stage clinical studies, and for palbociclib in randomized studies in combination with hormone therapy (10, 11). CDK4/6 inhibition with palbociclib has led to substantial increased disease control in ER-positive breast cancer, although CDK4/6 inhibitors typically induce tumor stabilization with only modest increased rates of tumor shrinkage (11). A major limitation of CDK4/6 inhibitors is cytostasis, as CDK4/6 inhibition blocks cell-cycle progression in G0–G1 (12, 13). This cytostatic response limits the response rate to CDK4/6 inhibitors in advanced breast cancer, and may limit the effectiveness of CDK4/6 inhibitors in early breast cancer where the aim is to eradicate micrometastatic disease.

PIK3CA mutations occur in approximately 40% of ER-positive breast cancers (3), and activation of the PI3K signaling is prominent as cancers become resistant to endocrine therapy (14). Prior work has identified PI3K inhibitors as synergistic partners of CDK4/6 inhibitors (15, 16); however, the subset of cancers that would benefit from this combination has not been clearly defined.

Here, we show that CDK4/6 inhibition in breast cancer cells is limited by an inability to induce complete and durable cell-cycle arrest, due to early adaptation mediated by persistent G1–S-phase cyclin expression and CDK2 signaling. We show that therapies that inhibit the PI3K–AKT–mTOR pathway synergize with CDK4/6 inhibitors through blockade of early adaptation combined with apoptosis induction. We go on to elucidate the mechanisms of acquired resistance of ER-positive breast cancers to CDK4/6 inhibition that occur through RB1 loss or CCNE1 amplification, and identify therapeutic strategies for acquired resistant cancers with CCNE1 amplification.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

All cell lines were obtained from ATCC or Asterand and maintained according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell lines were banked in multiple aliquots on receipt to reduce risk of phenotypic drift and identity confirmed by STR profiling with the PowerPlex 1.2 System (Promega)

Compound screen

MCF-7 and T47D cells were screened with three commercially available drug libraries from Prestwick (http://www.prestwick-chemical.com/prestwick-chemical-library.html), US drugs (http://www.msdiscovery.com), and Enzo (http://www.enzolifesciences.com/BML-2841/screen-well-reg-fda-approved-drug-library/). Cells were seeded into 384-well plates and half of the plates treated with compound library plus DMSO (vehicle) and half with compound library plus palbociclib at the survival fraction 80 (SF80) concentration. Cell number was assessed after 72-hour exposure using CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega). Each plate in the screen was performed in triplicate. To assess the effect of compound on sensitivity to palbociclib, the log2 ratio between growth in palbociclib plates and vehicle plates was assessed and expressed as a z score, with SD estimated from the median absolute deviation as described previously (17).

Cell staining, image acquisition, and analysis

Cells were seeded in 384-well View Plate (6007460, PerkinElmer), exposed to palbociclib for 24 or 72 hours, and labeled with 10 μmol/L bromodeoxyuridine (BrdUrd; B5002-1G, Sigma-Aldrich) or 5 μmol/L EdU (A10044, Invitrogen) for the indicated times prior to fixation and permeabilization. Cells were stained with mouse anti-BrdUrd (BD55627) and secondary antibody Alexa 488, anti-tubulin (MCA78G, AbD Serotec) and secondary Alexa 647, and DAPI (D9542, Sigma-Aldrich). EdU was stained with Click-iT Cell Reaction Buffer Kit (C10269) using 5 μmol/L Alexa-Azide647 (A10277, Invitrogen). Four fields per well were imaged with the Operetta microscope, 10 × objective lens. The number of nuclei (DAPI staining), percentage of BrdUrd-positive cells (BrdUrd staining vs. number of nuclei), and cell area were measured in more than 1,000 cells using Columbus software (Perkin Elmer). Experiments were performed in triplicates.

Droplet digital PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from cells and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The detection of cylcin E1 amplification by digital PCR was performed with a CCNE1 Taqman Copy Number Variation Assay (Hs07158517_cn) and a TERT TaqMan Copy Number Reference Assay (4403316) from Life Technologies on a QX-100 droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) system (Bio-Rad). To detect RB1 pM695fs*26, we designed a primer probe combination targeting RB1 c.2083-2084insA: pM695fs*26. Digital PCR was performed as described previously (18, 19). The ratio of CCNE1:TERT was calculated using the Poisson distribution in QuantaSoft. The RB1 pM695fs*26 fraction was assessed as published previously (18).

Statistical analysis

For in vitro studies, all statistical tests were performed with GraphPad Prism version 5.0 or Microsoft Excel. Unless stated otherwise, P values were two-tailed and considered significant if P < 0.05. Error bars represent SEM of three experiments.

Results

Early adaptation to CDK4/6 inhibition in ER-positive breast cancer cells

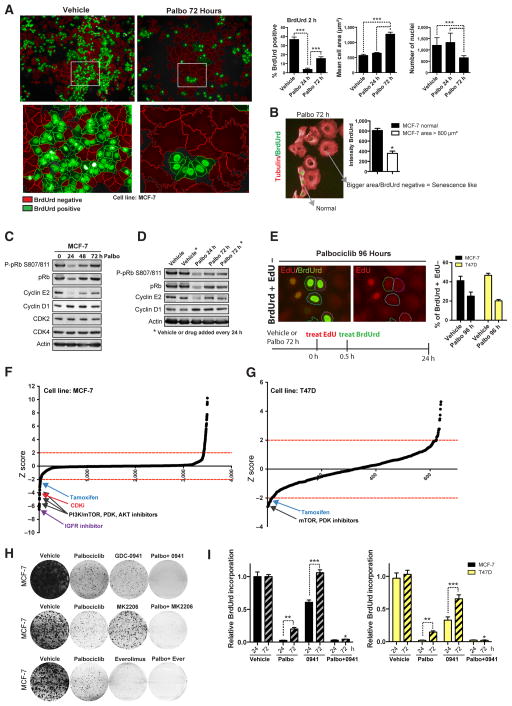

We assessed the steadiness of cell-cycle arrest induced by CDK4/6 inhibition in the ER-positive breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and T47D. Palbociclib treatment induced acute cell-cycle arrest after 24 hours as shown by reduced BrdUrd incorporation (Fig. 1A), and after 72- to 96-hour treatment led to a senescence-like morphology (cell flattening with increased cell area) and reduced cell number (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. S1A). However, prolonged palbociclib treatment over 72 hours was also accompanied by a low-level recovery of cells entering S-phase (BrdUrd positive) that were significantly smaller than the arrested cells (Fig. 1A and B). Accordingly, palbociclib inhibited pRB phosphorylation after 24 hours treatment (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. S1B), but pRB S807/811 phosphorylation and cyclin E2 expression returned to almost baseline levels despite continuous exposure to palbociclib over 72 hours. In addition, palbociclib induced cyclin D1 accumulation over a 72- to 96-hour period (Figs. 1C and D and 2A), likely reflecting arrest of cells in G1. Restoration of pRB S807/811 phosphorylation occurred even when palbociclib was replaced every 24 hours over a 72-hour period, indicating that the restoration did not reflect degradation of palbociclib (Fig. 1D). Cyclin E1 was expressed at low levels and we did not observe significant changes in response to palbociclib (data not shown; ref. 20). Dual pulse labeling with EdU for 30 minutes followed by BrdUrd for 24 hours confirmed that cells were able to transition G1–S phase despite CDK4/6 inhibition (green, BrdUrd+EdU−, Fig. 1E). In addition, cells transition through S-phase into later stages of the cell cycle (red, BrdUrd−EdU+, Supplementary Fig. S1C).

Figure 1.

Early adaptive resistance limits the efficacy of CDK4/6 inhibition. A and B, MCF-7 cells treated with 500 nmol/L palbociclib for 24 or 72 hours as indicated followed by 2 hours exposure to BrdUrd. A, images show BrdUrd-positive cells (green) and BrdUrd-negative cells (red). Graphs show number of nuclei (DAPI staining), percentage of BrdUrd–positive cells, and cell area (***, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test). B, BrdUrd staining (green) and tubulin (red) illustrate that BrdUrd-negative cells correlate with extended cell area (senescence like phenotype; *, P < 0.05, Student t test). C and D, Western blot analysis of lysates from MCF-7 cells treated for 24 to 72 hours with palbociclib (Palbo). *, addition of fresh vehicle or drug every 24 hours over a 72-hour period. E, MCF-7 cells treated with palbociclib for 72 hours followed by 0.5 hours exposure to EdU, then washed and exposed to BrdUrd for another 24 hours. Graph shows percentage of BrdUrd-positive–EdU-negative cells. F, effect of the drug library on the relative sensitivity to palbociclib expressed as a z score, with z scores below −2 indicating increased sensitivity to palbociclib. Main hits are indicated with arrows. H, clonogenic survival assays in MCF-7 cells treated continuously for 14 days with vehicle, 500 nmol/L palbociclib, 250 nmol/L GDC-0941 (0941; PI3K inhibitor), or 100 nmol/L MK2206 (AKT inhibitor) or 100 nmol/L everolimus (Ever; mTOR inhibitor), and the indicated combinations with palbociclib. I, BrdUrd incorporation measured by ELISA and corrected for viable cell number. Cells treated with vehicle, palbociclib, GDC-0941, or the combination for 24 or 72 hours (*, P < 0.05 palbociclib vs. combination at 72 hours, two-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test; **, P < 0.01 palbociclib 24 hours vs. 72 hours; ***, P < 0.001 GDC0941 24 hours vs. 72 hours, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest).

Figure 2.

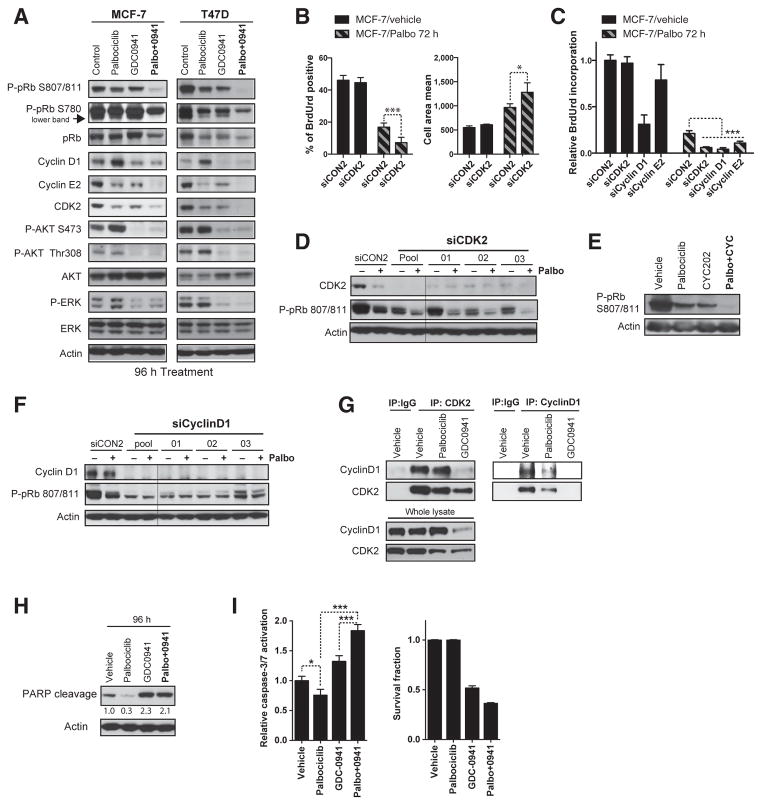

Early adaptation to CDK4/6 inhibition is mediated by noncanonical cyclin D1–CDK2 interaction. The addition of PI3K inhibitors reduces expression of G1–S-phase regulators and induces apoptosis. A and H, Western blot analysis of cell lysates from MCF-7 and T47D cell treated for 96 hours with vehicle, 500 nmol/L palbociclib (Palbo), 250 nmol/L GDC-0941 or combination and blotted with the indicated antibodies. B and C, cells transfected for 4 days with individual siRNAs or SMARTpool targeting CDK2, cyclin D1, or cyclin E2 and treated with vehicle or palbociclib for 72 hours. B, BrdUrd staining and cell area quantified with Columbus software (***, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05, Student t test). C, BrdUrd incorporation-ELISA assay (***, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test). D–G, Western blot analysis of MCF-7 cells lysates. D and F, cells transfected for 5 days with individual siRNAs or pools siRNAs targeting CDK2 or cyclin D1 and treated with vehicle or palbociclib for 96 hours. E, cells treated with vehicle, 500 nmol/L palbociclib, 10 μmol/L CYC202, or the combination for 72 hours. G, CDK2 immunoprecipitation (left) and cyclin D1 immunoprecipitation (right), or control normal IgG, blotted for CDK2 and cyclin D1. I, relative caspase-3/7 activation and survival fraction in MCF-7 cells treated as in A (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test).

Combination of CDK4/6–PI3K inhibition prevents early adaptation

Our experiments suggest that there is early adaptation that limits the cell-cycle arrest induced by CDK4/6 inhibition. To investigate the factors that underlie this early adaptation, we conducted a sensitization screen to identify compounds that synergized with palbociclib (see Materials and Methods). A 3,520 compound library was used in MCF-7 cells, with a repeat screen with 640 targeted anticancer drugs in T47D cells (Fig. 1F and G and Supplementary Fig. S1D). Many cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs had an antagonistic interaction with palbociclib (Supplementary Fig. S1E), as anticipated through palbociclib-arresting cells in G0–G1 (21).

Multiple compounds that inhibit the PI3K pathway, such as PDK, AKT, and mTOR inhibitors, and the selective estrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen, synergized with palbociclib in both cell lines, along with IGF1 receptor (IGF1R) inhibitor and the pan-CDK inhibitor flavopiridol in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 1F and G and Supplementary Fig. S1D). Short-term cell survival (Supplementary Fig. S1F and S1G, combination index 0.26 for 250 nmol/L GDC-0941/500 nmol/L palbociclib) and long-term clonogenic assays (Fig. 1H) confirmed increased sensitivity to palbociclib when combined with either the PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941, the AKT inhibitor MK2206, or the mTOR inhibitor everolimus. In MCF-7 and T47D cells, the combination of CDK4/6 and PI3K inhibition blocked the reentry into S-phase (Fig. 1I), suggesting that PI3K inhibition synergized with CDK4/6 inhibitors, in part, through blocking early adaptation.

Across a large panel of breast cancer cell lines, the combination of CDK4/6 and PI3K inhibition was active specifically in ER-positive cell lines with activating mutations in the PI3K pathway (***, P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA, Supplementary Fig. S2A and S2C). The combination of palbociclib and GDC-0941 did not increase sensitivity compared with monotherapy in vitro in cells with intrinsic resistance to either palbociclib (such as the pRb-null cells) or GDC-0941, suggesting the patient population for combination development (Supplementary Fig. S2B, S2D, and S2E).

Early adaptation to CDK4/6 inhibitors is mediated by G1–S-phase cyclins and CDK2

To investigate how PI3K inhibition blocked early adaptation, we studied the CDK4/6–pRb pathway by Western blot analysis in MCF-7 and T47D cells exposed to palbociclib, GDC-0941, or the combination for 72 to 96 hours (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S3A). We noted that AKT phosphorylation was modestly increased by chronic exposure to palbociclib, which correlates with sustained expression of E2F-induced G1–S-phase regulators such as cyclin E2 or CDK2 (Fig. 2A), and failure to fully inhibit pRB phosphorylation (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S3A). Combination of PI3K and CDK4/6 inhibition resulted in loss of pRB S807/811 and S780 phosphorylation, with concomitant reduction of cyclin E2 and CDK2 expression. Moreover, palbociclib-induced cyclin D1 accumulation was markedly reduced by the addition of GDC-0941. IGF1R/InsR inhibitors also synergized with CDK4/6 inhibition in MCF-7 cells, highlighting the role of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling in CDK4/6 inhibitor adaptation, potentially by feedback activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase (Supplementary Fig. S3B–S3D). Our results suggest that early adaptation following to CDK4/6 inhibition depends on PI3K signaling whereby sustaining expression of G1–S-phase cyclins.

We noted that the pan-CDK inhibitor flavopiridol also sensitized tumor cells to palbociclib in the compound screen (Fig. 1F) evoking a potential role for another CDK in early adaptation. To explore a compensatory role of CDK2 in mediating early adaptation, we undertook transient mRNA knockdown experiments. Silencing of CDK2 alone with siRNA had a very limited effect on S-phase entry and cell area likely because ER-positive MCF-7 cells rely on CDK4/6 for ensuring pRB phosphorylation (Fig. 2B and C). In contrast, in combination with palbociclib, CDK2 knockdown increased the fraction of cell cycle–arrested cells and increased cell area (senescence like morphology) both using pooled or individual siRNAs (Fig. 2B, C, and Supplementary Fig. S3E–S3G). Silencing CDK2 with siRNA (Fig. 2D) or with the CDK2 inhibitor CY202 (Fig. 2E) also resulted in further suppression of pRB S807/ 811 phosphorylation in combination with palbociclib.

We further investigated how CDK2 enabled cell-cycle progression despite CDK4/6 inhibition. We reasoned that cyclin D1 upregulation in cells treated with palbociclib alone could elicit a CDK2-coordinated progression into S-phase (Figs. 1C and D and 2A). Silencing of cyclin D1 both with pooled or individual siRNAs had a prominent effect in untreated MCF-7 cells, reflecting the key role of CDK4/6-cyclin D1 controlling baseline cell cycle (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. S3H). Nonetheless, increased cell-cycle arrest was induced by cyclin D1 knockdown in palbociclib-treated cells, which also resulted in a more profound effect on pRB dephosphorylation than palbociclib alone (Fig. 2F). Accordingly, CDK2 and cyclin D1 coimmunoprecipitated (Fig. 2G), suggesting that cyclin D1 may contribute to CDK2 activation by direct interaction. The interaction between CDK2 and cyclin D1 remained intact despite treatment with palbociclib, but was abolished by GDC-0941 treatment likely due to cyclin D1 downregulation following PI3K blockade. In agreement with cyclin E2 being an E2F-target gene and partner of CDK2, we observed that cyclin E2 expression recovered despite CDK4/6 inhibition (Fig. 1C), which could lead to sustained CDK2 activation. In line with this, knockdown of cyclin E2 significantly increased cell-cycle arrest in combination with palbociclib (Fig. 2C).

Overall our data suggest that early adaptation that follows to CDK4/6 blockade is mediated by the noncanonical CDK2/ cyclin D1 complex promoting pRb phosphorylation recovery. The cyclin E2 rebound is likely a consequence of CDK2/cyclin D1 activity and eventually triggering S-phase entry. Importantly, PI3K signaling blockade downregulates G1–S-phase cyclins that lead to CDK2 activation and act synergistically to suppress tumor cell proliferation.

Combination of CDK4/6 and PI3K inhibition increases apoptosis

We examined whether the effects of the PI3K inhibitor combination were solely through a greater induction of cell-cycle arrest and/or induction of apoptosis. Although, the arrest induced by palbociclib was accompanied by reduced PARP cleavage (at 96 hours), GDC-0941 alone or in combination with palbociclib increased PARP cleavage (Fig. 2H), active caspase-3/7 (Fig. 2I), and reduced senescence-like morphology (Supplementary Fig. S4A). To assess whether the addition of GDC-0941 could induce apoptosis even in cells previously arrested by palbociclib, we staged the addition of GDC-0941 for 6, 18, and 24 hours after 72 hours of palbociclib pretreatment, again observing an induction of caspase-3/7 activation compared with palbociclib alone (Supplementary Fig. S4B). The staged addition of GDC-0941 to cells arrested with palbociclib resulted in near complete loss of colonies, demonstrating that PI3K inhibition induced death of palbociclib-arrested cells (Supplementary Fig. S4C). Therefore, the combination is highly effective, resulting in profound loss of clonogenic capacity through profound cell-cycle arrest accompanied by apoptosis.

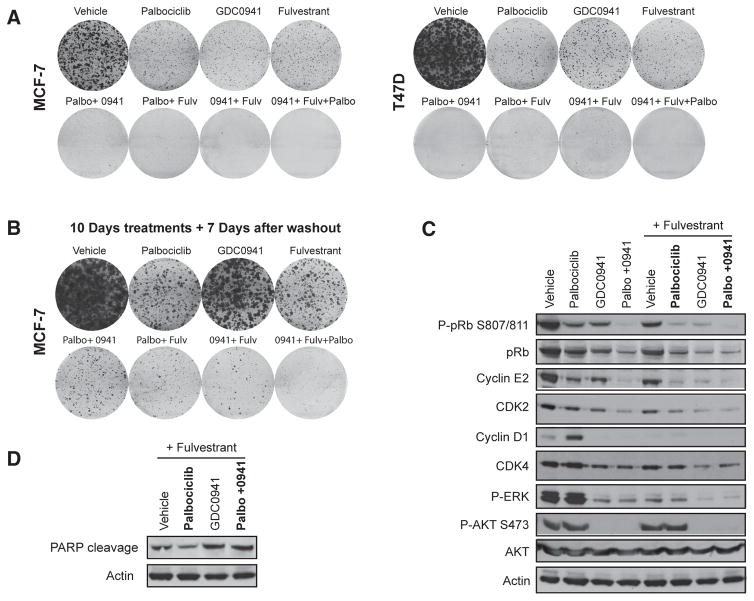

The triplet combination of ER, CDK4/6, and PI3K targeting has greater efficacy than either doublet

In clinical trials, both CDK4/6 inhibitors and PI3K inhibitors are being developed in combination with hormone therapies in ER-positive breast cancer. We examined whether the triplet combination of the estrogen receptor degrader (SERD) fulvestrant, palbociclib, and GDC-0941 would be more effective than the corresponding doublets, in particular, compared with the palbociclib–fulvestrant doublet. In both MCF-7 and T47D cells, continuous exposure to the triplet resulted in significant reduction of colonies, compared with either doublet (Fig. 3A). The clonogenic assays were repeated with 10 days of treatment, followed by washout for 7 days to allow for regrowth of any surviving cells (Fig. 3B). In all doublets, surviving cells were able to repopulate colonies, whereas in the triplet, there was no regrowth of colonies. In addition, the triplet combination reduced more pRB S807/811 phosphorylation and CDK2 and cyclin E2 expression compared with the palbociclib–fulvestrant doublet (Fig. 3C) and increased PARP cleavage (Fig. 3D). Therefore, the well-documented increased synergy between endocrine therapy and CDK4/6 inhibition likely shares the same mechanism as CDK4/6 and PI3K combined inhibition through inhibition of G1–S regulators, with the addition of GDC-0941 further decreasing expression of G1–S-phase regulators and leading to apoptosis.

Figure 3.

The triplet combination of ER degradation, CDK4/6 inhibition, and PI3K inhibition is more active than doublet combinations. A–D, MCF-7 or T47D cells exposed to 500 nmol/L palbociclib (Palbo), 250 nmol/L GDC-0941 (0941), 100 nmol/L fulvestrant (Fulv), or the indicated drug combinations. A, clonogenic survival assays for 14 days. B, clonogenic survival assay in MCF-7 cells treated for 10 days before drugs were washed and colonies were allowed to grow for a further 7 days. C and D, Western blot analysis of lysates from T47D cells blotted with the indicated antibodies.

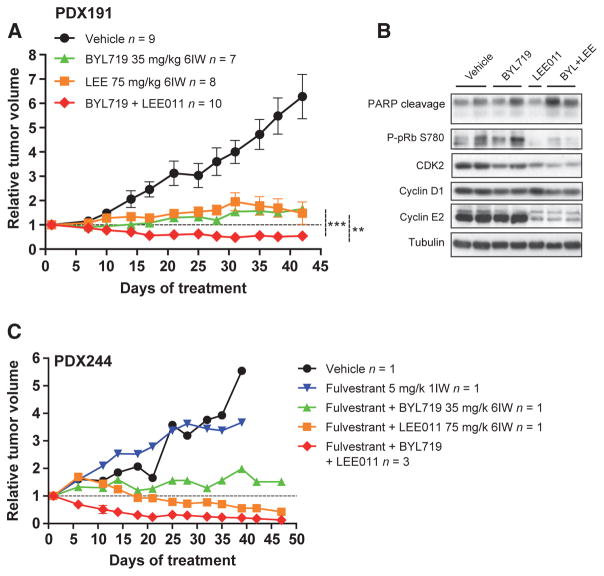

Combination of CDK4/6 and PI3K inhibition is efficacious in patient-derived tumor xenografts

We examined whether CDK4/6 and PI3K inhibitor combinations were efficacious in vivo. We generated patient-derived tumor xenograft (PDX) from patients with ER-positive breast cancer, and treated these with combinations of the CDK4/6 inhibitor LEE011 and the PI3Kα inhibitor BYL719. We chose PDX191, a CCND1-amplified tumor, and PDX244, a model harboring an ESR1 p.Y537S mutation with concomitant loss in CDKN2A/B (encoding for p16INK4A and p15INK4B, respectively). In model PDX191, both CDK4/6 and PI3K inhibitor monotherapy exhibited significant tumor growth reduction compared with vehicle-treated controls, but resulted in disease progression (Fig. 4A; 48% and 66% relative tumor growth increase at day 43, respectively, vs. day 1). Notably, the combination of CDK4/6 and PI3K inhibition resulted in significantly greater antitumor activity and tumor regressions (−45%) when compared with each agent alone. The combination of CDK4/6 with PI3K inhibition was well tolerated on the basis of minimal changes in mouse body weight (Supplementary Fig. S6A). LEE011 had no effect on PI3K pathway markers (data not shown) in tumor xenografts but reduced phophorylated pRb (Fig. 4B). The combination of both drugs increased PARP cleavage and reduced the expression of S-phase regulators mimicking the result observed in vitro.

Figure 4.

Duplet and triplet combination is efficacious in human-derived xenografts. A, relative tumor growth of PDX191 following vehicle, BYL719 (35 mg/kg, once daily, 6IW), LEE011 (75 mg/kg, once daily, 6IW), or the combination (**, P < 0.01;***, P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA). The total number of tumors in each arm (n) and SEM of each point are indicated. B, Western blots with the indicated antibodies in PDX191 after 42 days of vehicle, BYL719, LEE011, or the combination. Each lane belongs to one individual tumor. C, relative tumor growth of PDX244 following vehicle, fulvestrant (5 mg/kg, i.p., 1IW), fulvestrant plus BYL719, fulvestrant plus LEE011, and fulvestrant plus BYL719 plus LEE011 treatment.

We examined the triplet combination of fulvestrant, LEE011, and BYL719 in PDX244. The triplet combination induced responses in all animals with a rapid and marked reduction (−87%) in tumor volume after 47 days of treatment (Fig. 4C). Of note, this experiment was conducted using a recently described “one animal per model and treatment” (1 × 1 × 1) experimental design, with enrichment of the triplet combination arm (22).

Acquired palbociclib resistance occurs through gain of cyclin E1 amplification or RB1 loss

We next developed cell lines with acquired resistance to palbociclib, to investigate the mechanism of acquired resistance, and contrast with early adaptation. Palbociclib-resistant MCF-7 (MCF-7pR) and T47D (T47pR) cells were derived through chronic exposure to 1 μmol/L palbociclib during 3 to 4 months. In MCF-7pR and T47DpR, CDK4/6 inhibition failed to induce the acute cell-cycle arrest and cell death seen in parental MCF-7 and T47D, confirming resistance (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Fig. S5A).

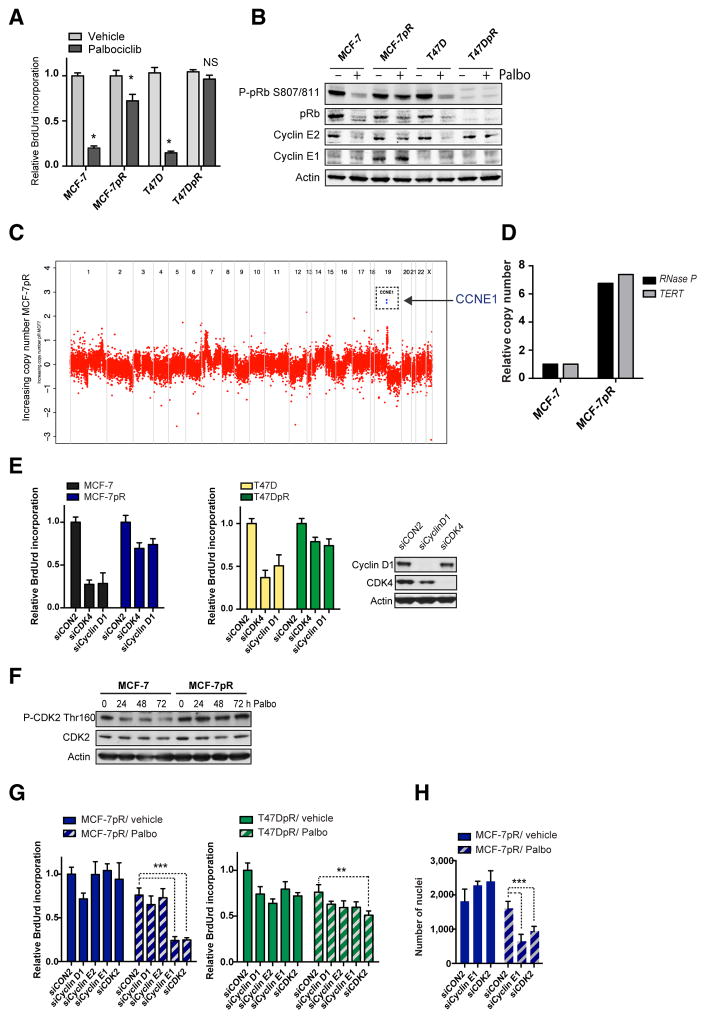

Figure 5.

Acquisition of resistance to CDK4/6 inhibition through RB1 loss or cyclin E1 amplification. A, BrdUrd incorporation-ELISA assay in parental (MCF-7, T47D) and palbociclib-resistant (MCF-7pR and T47DpR) cells treated with vehicle or palbociclib for 72 hours (*, P < 0.001 vehicle vs. palbociclib; NS, not significant, two-way ANOVA with Sidak multiple comparisons test). B, cells treated for 96 hours with vehicle or 500 nmol/L palbociclib, and lysates blotted with the indicated antibodies. C, comparison of copy number for MCF-7 parental versus MCF-7pR–resistant cell line. There is an amplification of chromosome 19q12 region encompassing the CCNE1 gene. D, CCNE1 relative copy number change assessment by ddPCR against two different reference genes, RNase P and TERT. E, BrdUrd incorporation-ELISA assay in cells transfected 4 days earlier with control siCON2 or SMARTpool siRNA targeting CDK4 or cyclin D1. Western blot analysis of the same experiment showing knockdowns in MCF-7 cells. F, Western blots of MCF-7 and MCF-7pR cells treated for 24, 48, and 72 hours with palbociclib (Palbo) and blotted phospho-CDK2 Thr160 and total CDK2. G and H, cells transfected for 4 days with control siCON2 or the indicated SMARTpool siRNAs and treated with vehicle or palbociclib for 72 hours. G, BrdUrd incorporation-ELISA assay adjusted with viable cell number. H, cell number after vehicle or palbociclib for 72 hours (**, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test).

We sought to understand the mechanisms through which the cell lines had acquired resistance. Western blots of lysates from MCF-7pR and T47DpR cells reveled loss of pRB expression in T47DpR (Fig. 5B). MCF-7pR cells underwent a substantial increase in cyclin E1 expression and CDK4/6 inhibition failed to reduce pRb phosphorylation compared with parental MCF-7 (Fig. 5B). Copy number profiling from exome sequencing of MCF-7 and MCF-7pR, confirmed relative amplification of CCNE1 and multiple de novo mutations in resistant MCF-7pR cells (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Fig. S5B and S5C). Gain of CCNE1 copy number in MCF-7pR cells was validated by digital PCR (Fig. 5D and Supplementary Fig. S5D).

In both MCF-7pR and T47DpR cells, siRNA silencing of CDK4 or CCND1 had a reduced effect on growth of MCF-7pR and T47DpR compared with parental MCF-7 and T47D (Fig. 5E), despite similar levels of reduced survival with the transfection/ toxicity control siRNA targeting ubiquitin B (UBB, Supplementary Fig. S5E). Silencing of CDK4 and of CCND1 (cyclin D1) was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 5E).

We next sought to understand whether CDK4/6-resistant cells rewired S-entry via CDK2. MCF-7pR cells sustained high levels of CDK2 Thr160 phosphorylation despite CDK4/6 inhibition (Fig. 5F). Moreover, silencing of CCNE1 or CDK2 alone in MCF-7pR cells had no effect on cell-cycle arrest, but resulted in substantially increased cell-cycle arrest and reduction in cell growth in combination with palbociclib (Fig. 5G and H and Supplementary Fig. S5F and S5G). None of the combinations had an acute effect in pRb-low T47DpR cells (Fig. 5G). Altogether, these results highlight that CDK4/6-resistant cells have lost their dependence on CDK4/6-cyclin D1 signaling, likely due to the acquired CCNE1 and RB1 alterations. Although pRb-low cells may have lost the G1-restriction point and are no longer susceptible of CDK4/6 or CDK2 blockade, CCNE1-amplified cells retain sensitivity to CDK2 blockade.

Acquired mutation in RB1 induces resistance to CDK4/6 blockade in PDX

To establish whether similar mechanisms of acquired resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors are seen in vivo, we took advantage of the CDK4/6-sensitive PDX244 model and developed acquired resistance to CDK4/6 blockade with LEE011 (Fig. 6A). During the first 40 days of treatment, 5 of 8 CDK4/6 inhibitor-treated tumors underwent regression compared with the vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 6A). After this period, tumors started to regrow under drug pressure. Western blot analysis showed a decrease of pRb protein levels in 4 of 7 CDK4/ 6-acquired resistant tumors and a sustained expression of the E2F target cyclin E2, in contrast to CDK4/6 inhibitor-sensitive PDX244 (Fig. 6B and Supplementary Fig. S7).

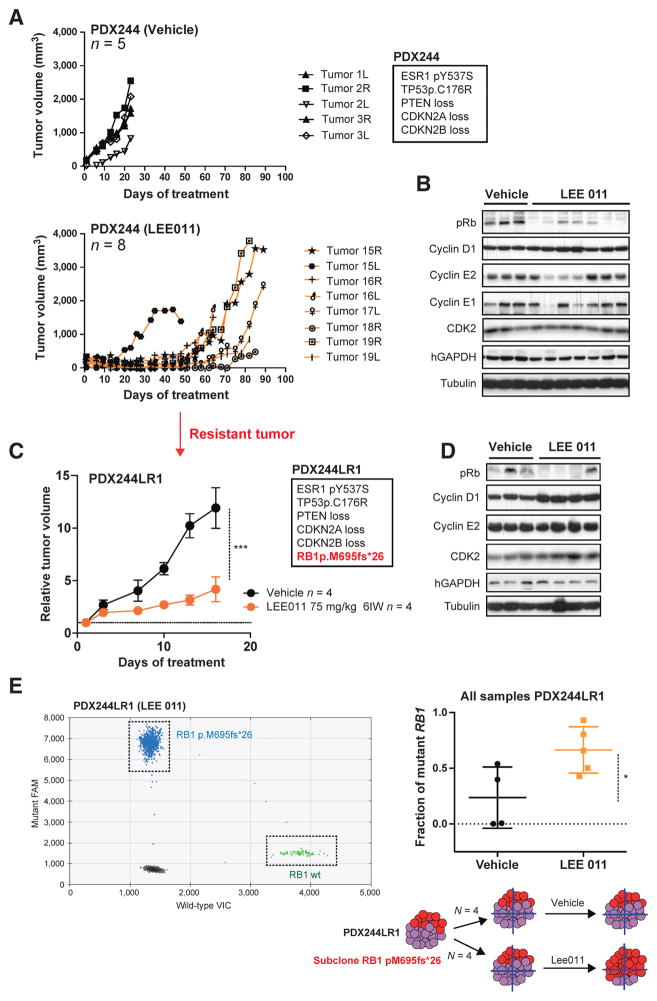

Figure 6.

Acquisition of resistance to CDK4/6 inhibition through RB1 mutation in PDX. A, tumor growth of PDX244 following vehicle (top graphic) or LEE011 (75 mg/kg, once daily, 6IW; bottom graphic) treatment. Tumor volume (mm3) is shown over the days of treatment. The total number of mice in each arm (n) and the relevant genetic alterations of PDX244 are indicated. B, Western blots with the indicated antibodies in PDX244 after 23 days of vehicle treatment or 89 days of LEE011 treatment. Each lane belongs to one individual tumor. C, relative tumor growth of PDX244LR1 following vehicle or LEE011 treatment (***, P < 0.001, Student t test). The relevant genetic alterations of PDX244LR1 are indicated. D, Western blots with the indicated antibodies in PDX244LR1 after 16 days of vehicle or LEE011 treatment. Each lane belongs to one individual tumor. E, RB1 pM695fs*26 fraction in vehicle or LEE011-treated samples from PDX244LR1 assessed by ddPCR against RB1 wild-type (*, P < 0.05, Student t test).

We hypothesized that the CDK4/6-acquired resistance phenotype was due to the gain of a genomic alteration, as resistance was confirmed in a serial passage of an LEE011-relapsed tumor (PDX244LR1; Fig. 6C). Genomic characterization of PDX244LR1 showed the acquisition of an RB1 frameshift mutation (RB1 p.M695fs*26). Interestingly, despite the presence of an RB1 mutation, transplanted tumors remained partially sensitive to CDK4/6 inhibition. To investigate the potential reason for this, we performed Western blot analysis of PDX244LR1 tumors. We confirmed that treatment with LEE011 did not result in downmodulation of cyclin E2 and noted that the levels of pRb expression were variably low across the individual tumors (Fig. 6D). We therefore reasoned that the acquired RB1 mutation could be subclonal. Digital PCR analysis of PDX244LR1 tumors showed that the RB1 mutation allele fraction increased from 0.25 in control tumors to 0.55 in CDK4/6-treated tumors (Fig. 6E). This result suggests that the RB1 mutation was subclonal in the resistant tumor, and that CDK4/6 inhibition resulted in selection of the RB1-mutant population (Fig. 6E).

Combination of CDK4/6–PI3K inhibitors does not resensitize cancers with acquired resistance but prevents CDK4/6 resistance

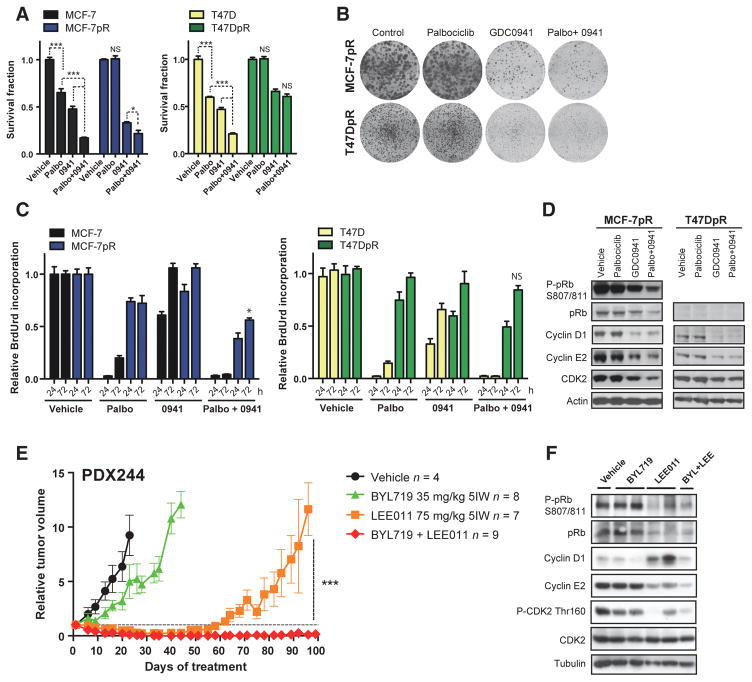

We next addressed whether CDK4/6 and PI3K inhibitor combinations could resensitize cell lines with acquired CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance. Although MCF-7pR and T47DpR cells exhibited similar levels of sensitivity to GDC-0941, GDC-0941 was not able to fully resensitize cells to CDK4/6 inhibitors (Fig. 7A and B). The combination did not suppress S-phase entry in the resistant MCF-7pR and T47DpR (Fig. 7C), and was unable to fully suppress pRb phosphorylation and cyclin E2 or CDK2 expression (Fig. 7D). The lack of combination effect was more evident in the pRb-low T47DpR cell line. In both cell lines, the addition of GDC-0941 substantially reduced cyclin D1 expression, yet this did not result in combination efficacy, confirming the loss of dependence to cyclin D1 of cells with CDK4/6 inhibitor acquired resistance (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

Early treatment with CDK4/6 plus PI3K inhibitors prevents acquisition of resistance in PDXs, but is not efficacious in resistant cells. A, relative growth of parental (MCF-7 and T47D) and palbociclib-resistant (MCF-7pR and T47DpR) cell lines treated for 6 days with control vehicle, 500 nmol/L palbociclib, 250 nmol/L GDC0941 (0941), or the combination (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; NS, not significant, two-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test). B, clonogenic survival assays in MCF-7pR and T47DpR cells treated for 14 days. C, BrdUrd incorporation-ELISA assays in cells treated for 24 or 72 hours (*, P < 0.05 palbociclib or GDC0941 vs. combination at 72 hours, two-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons test). D, Western blots of resistant cells treated for 96 hours as indicated. E, relative tumor growth of PDX244 following vehicle, BYL719, LEE011, or the combination (***, P < 0.0003 Student t test for LEE011 vs. BYL719 plus LEE011). F, Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies in PDX244 after 103 days of vehicle, BYL719, LEE011, or the combination. Each lane belongs to one individual tumor.

To assess whether PI3K could prevent the acquisition of resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors in vivo, we utilized the PDX244 model in the chronic treatment setting. Although LEE011 single agent induced a short partial response in 5 of 8 individual tumors, combination therapy resulted in a prolonged complete response in 7 of 9 tumors, preventing the outgrowth of CDK4/6-resistant tumors (Fig. 7E). Therefore, our data support the use of CDK4/6 and PI3K inhibitor combinations in CDK4/6 treatment–naïve tumors, to maximize tumor shrinkage and prevent the acquisition of resistance.

Discussion

Proliferation of hormone receptor–positive breast cancer is dependent on cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 (CDK4 and CDK6), which promote progression from the G1-phase to the S-phase of the cell cycle (23–28). CDK4/6 inhibitors have shown activity in breast cancer, particularly in combination with endocrine therapy (13, 23, 29). Efforts are being made to identify markers of sensitivity or resistance to CDK4/ 6 blockade. In the current study, we explore resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors and the molecular mechanisms that determine sensitivity to novel combination therapies in ER-positive breast cancers. We show that CDK4/6 inhibition as monotherapy is limited by early adaptation, with cyclin D1 and G1–S cyclins mediating residual cell-cycle entry via CDK2. This highlights the importance of combining CDK4/6 inhibitors with therapies that block expression of cyclin D1 and other G1–S cyclins, block early adaptation, and induce greater cell-cycle arrest.

Our study demonstrates that in response to chronic CDK4/6 inhibition, there is a PI3K-dependent upregulation of cyclin D1 along with CDK2-dependent pRb phosphorylation and S-phase entry (Fig. 1C and D). Prior research has shown, particularly in the absence of CDK4/6 (30), that cyclin D1 can bind to and activate CDK2 (31), and that this complex has the ability to phosphorylate pRb and other substrates (32). Here we demonstrate that cyclin D1 and CDK2 directly interact upon CDK4/6 inhibition. Whereas we show that cyclin D1, and downstream cyclin E2 expression, promotes ongoing cell-cycle entry in ER-positive breast cancer, in other cancer types, cyclin E1 may be the driver of primary resistance (16, 20, 33), likely reflecting tumor or cell-type differences in the cyclins that promote G1–S transition. In MCF-7 cells, cyclin E1 levels remained low despite CDK4/6 inhibition and cyclin E1 silencing in combination with palbociclib failed to reduce pRb phosphorylation, suggesting that cyclin E1 does not promote early adaptation in our model (data not shown).

Although CDK4/6 inhibition induces cell-cycle arrest accompanied by phenotypes of senescence, a low level of cells continue to reenter the cell cycle, and on withdrawal of CDK4/6 inhibition the cell-cycle arrest/senescent phenotype is readily reversible (Supplementary Fig. S4D; refs. 34–36). The efficacy of palbociclib is also limited by inhibition of apoptosis during the cell-cycle arrest. We demonstrate that the combination of CDK4/6 and PI3K inhibition induces a different mode of arrest compared with palbociclib alone, characterized by not only sustained growth arrest, but also increased apoptosis in vitro, as well as tumor regression in vivo.

Acquired resistance to palbociclib in vitro reflects loss of dependence on cyclin D1-CDK4/6, although the molecular mechanism of this loss of dependence is multifactorial through loss of pRb expression and overexpression of cyclin E1. Similar mechanisms of acquired resistance to palbociclib have recently been reported in ovarian cancer cell lines in vitro (37). Although the PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941 still modulates cyclin D1 expression in acquired resistant cells, the acquired lack of dependence on cyclin D1 results in an inability to restore sensitivity to CDK4/6 inhibition. However, we show that an upfront combination of CDK4/ 6-PI3K inhibitors prevented the development of resistance. Our data suggest that combinations of PI3K inhibitors and CDK4/6 inhibitors are best employed clinically in the treatment ER-positive CDK4/6 inhibitor-naïve cancers, namely, pRb proficient with low levels of cyclin E1 expression tumors.

In summary, these findings support the clinical development of combinations of CDK4/6 and PI3K/mTOR inhibitors in ER-positive cancers. Our data also support the development of triplet combinations of CDK4/6, PI3K, and fulvestrant in ER-positive breast cancer. These combinations have the potential to overcome the cytostatic nature of CDK4/6 inhibition, and are being taken forward in multiple clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Beach of the Blizzard Institute, Javier Hernandez of the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, and Jose Jimenez from VHIO for discussion of data and technical advice, respectively. Emmanuelle di Tomaso and Giordi Caponigro from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation provided LEE011 and BYL719 for the in vivo work. The authors also acknowledge NHS funding to the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and the ICR. The authors thank GHD, the FERO Foundation, and the Orozco Family for supporting this study (V. Serra and J. Baselga).

Grant Support

This research was funded by Breast Cancer Now with generous support from the Mary-Jean Mitchell Green Foundation, the Avon foundation, and Cancer Research UK C30746/A16642 (to N.C. Turner); and by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III PI13-01714, CP14/00228 and the Catalan Agency AGAUR (2014 SGR 1331) Research Grants (to V. Serra).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

M. Bellet has received speakers’ bureau honoraria from Astra Zeneca. J. Cortes has received speakers’ bureau honoraria from Novartis. M. Dowsett reports receiving a commercial research grant from Pfizer and has received speakers’ bureau honoraria from Pfizer. L.-A. Martin reports receiving a commercial research grant from PUMA and Pfizer. N.C. Turner reports receiving a commercial research grant from Pfizer and Roche and is a consultant/advisory board member for Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design: M.T. Herrera-Abreu, M. Palafox, U. Asghar, J. Cortés, J. Baselga, N.C. Turner, V. Serra

Development of methodology: M.T. Herrera-Abreu, M. Palafox, U. Asghar, M.A. Rivas, I. Garcia-Murillas, A. Pearson, C.J. Lord, V. Serra

Acquisition of data (provided animals, acquired and managed patients, provided facilities, etc.): M.T. Herrera-Abreu, M. Palafox, U. Asghar, M.A. Rivas, I. Garcia-Murillas, M. Guzman, O. Rodriguez, J. Grueso, M. Bellet, R. Elliott, S. Pancholi, C.J. Lord, M. Dowsett, L.A. Martin

Analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis): M.T. Herrera-Abreu, M. Palafox, U. Asghar, R.J. Cutts, I. Garcia-Murillas, A. Pearson, M. Dowsett, C.J. Lord, N.C. Turner, V. Serra

Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: M.T. Herrera-Abreu, M. Palafox, M. Dowsett, L.A. Martin, N.C. Turner, V. Serra

Administrative, technical, or material support (i.e., reporting or organizing data, constructing databases): M.T. Herrera-Abreu, V. Serra

Study supervision:M.T. Herrera-Abreu, J. Cortés, J. Baselga, N.C. Turner, V. Serra

References

- 1.Yeo B, Turner NC, Jones A. An update on the medical management of breast cancer. BMJ. 2014;348:g3608. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal R, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Myhre S, Carey M, Lee JS, Overgaard J, et al. Integrative analysis of cyclin protein levels identifies cyclin b1 as a classifier and predictor of outcomes in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3654–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu Q, Geng Y, Sicinski P. Specific protection against breast cancers by cyclin D1 ablation. Nature. 2001;411:1017–21. doi: 10.1038/35082500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato J, Matsushime H, Hiebert SW, Ewen ME, Sherr CJ. Direct binding of cyclin D to the retinoblastoma gene product (pRb) and pRb phosphorylation by the cyclin D-dependent kinase CDK4. Genes Dev. 1993;7:331–42. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkhart DL, Sage J. Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:671–82. doi: 10.1038/nrc2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapiro G, Rosen LS, Tolcher AW, Goldman JW, Gandhi L, Papadopoulos KP, et al. A first-in-human phase I study of the CDK4/6 inhibitor, LY2835219, for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl) abstr 2500. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Infante JR, Shapiro G, Witteveen P, Gerecitano JF, Ribrag V, Chugh R, et al. A phase I study of the single-agent CDK4/6 inhibitor LEE011 in pts with advanced solid tumors and lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(5s) suppl; abstr 2528. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I, Boer K, Bondarenko IM, Kulyk SO, et al. Final results of a randomized Phase II study of PD 0332991, a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)-4/6 inhibitor, in combination with letrozole vs letrozole alone for first-line treatment of ER+/HER2-advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1; TRIO-18) [abstract]. Proceedings of the 105th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; 2014 Apr 5–9; San Diego, CA. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; Abstract nr CT101. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I, Boer K, Bondarenko IM, Kulyk SO, et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:25–35. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finn RS, Dering J, Conklin D, Kalous O, Cohen DJ, Desai AJ, et al. PD 0332991, a selective cyclin D kinase 4/6 inhibitor, preferentially inhibits proliferation of luminal estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer cell lines in vitro. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R77. doi: 10.1186/bcr2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asghar U, Witkiewicz AK, Turner NC, Knudsen ES. The history and future of targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:130–46. doi: 10.1038/nrd4504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller TW, Balko JM, Fox EM, Ghazoui Z, Dunbier A, Anderson H, et al. ERalpha-dependent E2F transcription can mediate resistance to estrogen deprivation in human breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:338–51. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vora SR, Juric D, Kim N, Mino-Kenudson M, Huynh T, Costa C, et al. CDK 4/6 inhibitors sensitize PIK3CA mutant breast cancer to PI3K inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:136–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franco J, Witkiewicz AK, Knudsen ES. CDK4/6 inhibitors have potent activity in combination with pathway selective therapeutic agents in models of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5:6512–25. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrera-Abreu MT, Pearson A, Campbell J, Shnyder SD, Knowles MA, Ashworth A, et al. Parallel RNA interference screens identify EGFR activation as an escape mechanism in FGFR3-mutant cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1058–71. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Murillas I, Schiavon G, Weigelt B, Ng C, Hrebien S, Cutts RJ, et al. Mutation tracking in circulating tumor DNA predicts relapse in early breast cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:302ra133. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gevensleben H, Garcia-Murillas I, Graeser MK, Schiavon G, Osin P, Parton M, et al. Noninvasive detection of HER2 amplification with plasma DNA digital PCR. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3276–84. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caldon CE, Sergio CM, Sutherland RL, Musgrove EA. Differences in degradation lead to asynchronous expression of cyclin E1 and cyclin E2 in cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:596–605. doi: 10.4161/cc.23409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts PJ, Bisi JE, Strum JC, Combest AJ, Darr DB, Usary JE, et al. Multiple roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:476–87. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao H, Korn JM, Ferretti S, Monahan JE, Wang Y, Singh M, et al. High-throughput screening using patient-derived tumor xenografts to predict clinical trial drug response. Nat Med. 2015;21:1318–25. doi: 10.1038/nm.3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner NC, Ro J, André F, Loi S, Verma S, Iwata H, et al. Palbociclib in hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:209–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt M, Fernandez de Mattos S, van der Horst A, Klompmaker R, Kops GJ, Lam EW, et al. Cell cycle inhibition by FoxO forkhead transcription factors involves downregulation of cyclin D. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7842–52. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7842-7852.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foster JS, Wimalasena J. Estrogen regulates activity of cyclin-dependent kinases and retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:488–98. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.5.8732680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:153–66. doi: 10.1038/nrc2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musgrove EA, Caldon CE, Barraclough J, Stone A, Sutherland RL. Cyclin D as a therapeutic target in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:558–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narasimha AM, Kaulich M, Shapiro GS, Choi YJ, Sicinski P, Dowdy SF. Cyclin D activates the Rb tumor suppressor by monophosphorylation. Elife. 2014:3. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.VanArsdale T, Boshoff C, Arndt KT, Abraham RT. Molecular pathways: targeting the cyclin D-CDK4/6 axis for cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:2905–10. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malumbres M, Sotillo R, Santamaría D, Galán J, Cerezo A, Ortega S, et al. Mammalian cells cycle without the D-type cyclin-dependent kinases Cdk4 and Cdk6. Cell. 2004;118:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiong Y, Zhang H, Beach D. D type cyclins associate with multiple protein kinases and the DNA replication and repair factor PCNA. Cell. 1992;71:505–14. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90518-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jahn SC, Law ME, Corsino PE, Rowe TC, Davis BJ, Law BK. Assembly, activation, and substrate specificity of cyclin D1/Cdk2 complexes. Biochemistry. 2013;52:3489–501. doi: 10.1021/bi400047u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caldon CE, Sergio CM, Kang J, Muthukaruppan A, Boersma MN, Stone A, et al. Cyclin E2 overexpression is associated with endocrine resistance but not insensitivity to CDK2 inhibition in human breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1488–99. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burd CE, Sorrentino JA, Clark KS, Darr DB, Krishnamurthy J. Deal AMMo-nitoring tumorigenesis and senescence in vivo with a p16(INK4a)-luciferase model. Cell. 2013;152:340–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartkova J, Horejsí Z, Koed K, Kramer A, Tort F, Zieger K, et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434:864–70. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor-Harding B, Aspuria PJ, Agadjanian H, Cheon DJ, Mizuno T, Greenberg D, et al. Cyclin E1 and RTK/RAS signaling drive CDK inhibitor resistance via activation of E2F and ETS. Oncotarget. 2015;6:696–714. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.