Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Approximately, 80% of the many cases of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) confirmed worldwide were diagnosed in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). The risk of the disease spreading internationally is especially worrying given the role of KSA as the home of the most important Islamic pilgrimage sites. This means the need to assess Arab pilgrims' awareness of MERS-CoV is of paramount importance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A cross-sectional study was carried out during Ramadan 2015 in the Holy Mosque in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Self-administered questionnaires were distributed to 417 Arab participants at King Fahad Extension, King Abdullah Prayer Extension and, King Abdullah Piazza Extension after Taraweeh and Fajr prayers.

RESULTS:

The mean MERS-CoV knowledge score was 52.56. Majority of the respondents (91.3%) were familiar with MERS-CoV. Saudis had significantly higher knowledge of MERS-CoV than non-Saudis (56.92 ± 18.55 vs. 44.91 ± 25.46, p = 0.001). Females had significantly more knowledge about consanguineous MERS-CoV than males (55.82 ± 19.35 vs. 49.93 ± 23.66, p = 0.006). The average knowledge was significantly higher in respondents who had received health advice on MERS-CoV (56.08 ± 20.86 vs. 50.65 ± 22.51, p = 0.024). With respect to stepwise linear regression, knowledge of MERS-CoV tended to increase by 14.23 (B = 14.23%, p = 0.001) in participants who were familiar with MERS-CoV, and by 8.50 (B = 8.50, p = 0.001) in those who perceived MERS-CoV as a very serious disease.

CONCLUSION:

There is a great need for educational programs to increase awareness about MERS-CoV.

Key words: Awareness, infection precautions, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Pilgrims, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is a new virus that was first discovered in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia in 2012.[1] Many cases of MERS-CoV have since been confirmed worldwide. Around 80% of the MERS-CoV cases were discovered and confirmed in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA).[2] It is estimated that 1625 cases have been diagnosed with MERS-CoV globally, with 1283 specifically in (KSA). At the time of publishing of this manuscript, 551 deaths had been recorded. In April 2014, the incidence of MERS-CoV dramatically increased and was found to be equal to the number of all cases detected before that month. Numerous hypotheses have been made to explain this dramatic increase in incidence.[2] The basic hypotheses being that viral change in the form of mutation facilitated the dissemination of the virus in health-care facilities and the transmission from animal to human. It seems that MERS-CoV has a predilection to specific months, leading to dramatic increases in incidence from March to April. Many studies have shown that camels may play a role in zoonotic transmission to humans.[2] The clinical features of MERS-CoV infection vary from very simple cases that can be managed in outpatient settings to very complicated ones that require admission to the intensive care unit. However, the most common symptoms are fever, cough, and shortness of breath, which are no different from other influenza infections.[3] The seriousness of MERS-CoV infection is a worldwide health concern.

Owing to the role of KSA plays as the host to the most important Islamic pilgrimage, the actual site of the pilgrimage becomes crowded with a congregation of two million pilgrims for Umrah during Ramadan. Furthermore, about six million pilgrims come to Saudi Arabia for Umrah throughout the year, and another two million, come to fulfill their fifth pillar of Islam, “Hajj.” These events put the pilgrims at an increased risk of contracting and transmitting infections both within and outside the KSA. Some countries such as Germany, UK, France, Italy, Tunisia, Malaysia, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates[4,5] reported incidences of MERS-CoV after their citizens returned from Hajj in 2013. The most common cause of hospital admissions during Hajj is respiratory diseases.[6] Assessing the different aspects of knowledge about MERS-CoV, and the protective precautions that can be taken against it among pilgrims will help to determine the need for MERS-CoV educational programs. To the best of our knowledge, there are hardly any studies that address issues relating to pilgrims.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out during Ramadan 2015 (July 2–13, 2015) in the actual Holy Mosque in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. The sample size was based on the requirement of 95% confidence limit with 5% precision rate and a proportion of 50% based on a pilot study due to limited previous studies. Self-administered structured questionnaires were distributed and collected from 417 Arab participants at their convenience at King Fahad Extension, King Abdullah Prayer Extension area, and King Abdullah Piazza Extension after Taraweeh and Fajr prayers. The data collectors introduced themselves to the respondents, briefed them about the study, and took their verbal consent. They handed out the questionnaires, which required 5 min to complete. All non-Arab pilgrims and those not willing to participate were excluded from this study.

The questionnaire had two main parts. The first part involved the sociodemographic characteristics, time of visiting Makkah, any health advice about the disease received, perception of the seriousness of MERS-CoV, familiarity with MERS-CoV, and whether he/she had ever caught MERS-CoV. The second part contained 31 structured questions, eliciting “Yes”, “No”, and “I do not know” responses, which dealt with knowledge about the disease in terms of symptomatology of MERS-CoV's modes of transmission, complications, and measures for preventing the transmission of the disease. The questionnaire was found to be reliable with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.875. Permission and ethical approval to conduct the study were granted by the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh.

IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS®) Version, 22.0 (Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for data analysis. Sociodemographic characteristics were reported using counts and percentages. Numerical data on age and knowledge of MERS-CoV were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD). Differences in respondents' knowledge about MERS-CoV across genders, age, nationality, etc., were assessed by independent t-tests/analysis of variance (ANOVA). Participants who selected the right answer were given a score of one for each of the 31 knowledge questions. Those who did not know the answer or answered incorrectly were given a zero for the question. The sum score out of 31 was multiplied by a constant to make a final score of 100. Multivariate stepwise linear regression model was used to identify the predictors associated with knowledge of MERS-CoV. The strength of the relationships was assessed by multiple correlation coefficients and adjusted R-square; p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

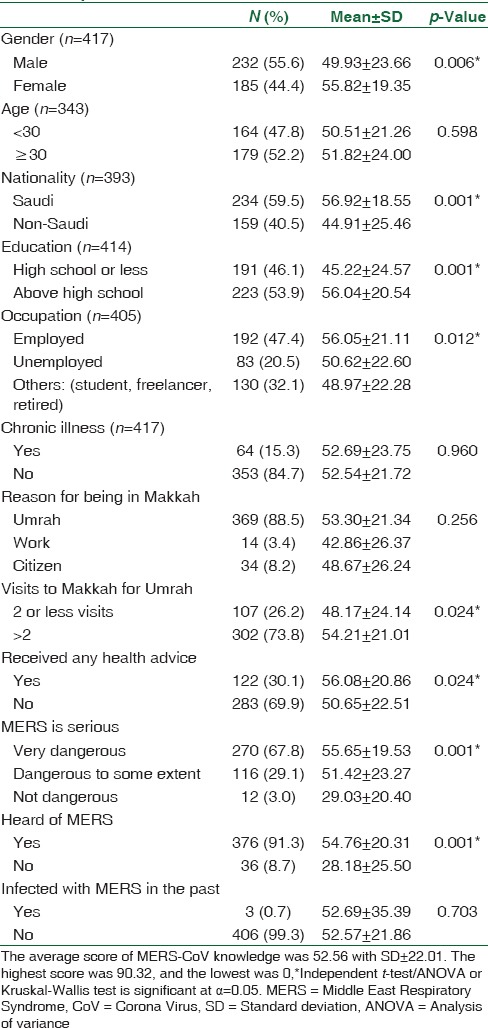

Our study enrolled 417 visitors to the holy mosque; 55.6% were males and 44.4% were females. The average age of the participants was 33 with an SD of 13.39, and range from 18 to 71 years. More than half of the participants were Saudis (56%), and 38% were from different Arab countries (10% were Egyptians, 5.7% from Morocco, 4.5% from United Arab of Emirates, 3.5% were Sudanese, and 3.1% from Kuwait and 1% were Qatari, Bahraini, Iraqi, Libyan, and Syrian); the remaining 5.7% did not indicate their nationalities. With regard to education, 46.1 had high school education or less, while the remaining 53.9% had more than high school education. When asked if they were familiar with MERS-CoV, 91% pilgrims replied affirmative. The average score of MERS-CoV knowledge was 52.56 with SD ± 22.01. The highest score was 90.32, and the lowest was 0. Three of the participants reported that they had had MERS-CoV. An Independent t-test was conducted to compare the knowledge of those who perceived MERS as “very serious” and “not serious”; the average knowledge score of the participants who perceived it as “very serious” was higher than those who thought it was “not serious” (55.65 ± 19.53 vs. 29.03 ± 20.40, p = 0.001). There was a significant difference in the scores between those who had heard of MERS-CoV and those who had not heard of it (54.76 ± 20.35 vs. 28.18 ± 25.5, p = 0.001). Saudi participants had higher knowledge scores than non-Saudis (56.92 ± 18.55 vs. 44.91 ± 25.46, p = 0.001). The MERS-CoV knowledge score was significantly associated with gender with female participants scoring higher than male participants (55.82 ± 19.35 vs. 49.93 ± 23.66, p = 0.006). The average knowledge score of participants who had been given advice was significantly higher than those who had not had any advice (56.08 ± 20.86, 50.65 ± 22.51, p = 0.024).

Those who had finished high school had a higher knowledge score (56.04 ± 20.54), whereas those with a high school diploma or less had a mean score of 45.22 ± 24.57, p = 0.001. There was no statistically significant association between knowledge of MERS-CoV and age, chronic disease, reason for visiting Makah, and those who had had MERS-CoV (> p = 0.05) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Arab pilgrims' knowledge about Middle East respiratory syndrome corona virus and its relation with sample characteristics

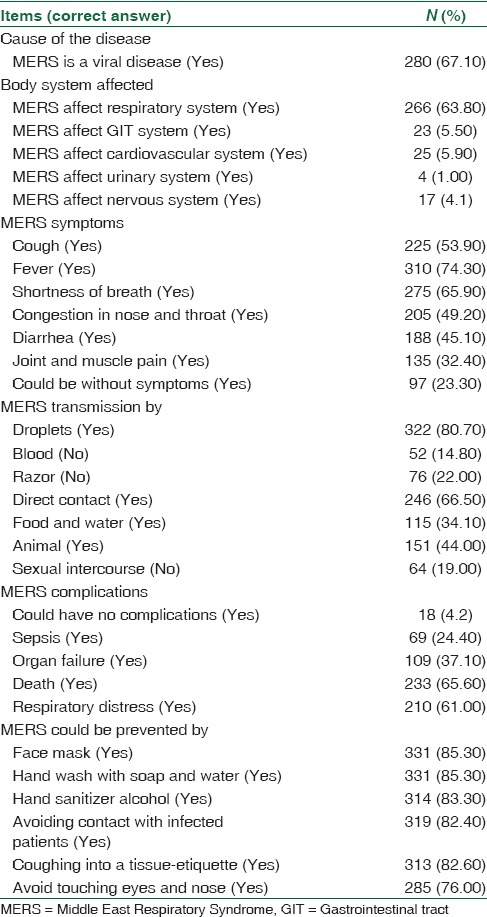

About 67% participants believed that the cause of MERS-CoV disease was viral in origin. With regard to the body system affected by MRES-CoV, the majority (64%) believed that it affected the respiratory system (Table 2). However, when asked about other systems only 5.5% believed that it might affect the gastrointestinal system, 5.9% the cardiovascular system, 1% the urinary system, and 4.1% said the nervous system. The most common symptoms MERS-CoV reported by study participants were fever (74%), shortness of breath (66%), cough (54%), congestion in nose and throat (49%), diarrhea (45%), joint and muscle pain (32%), and (22%) reported that it could present without any symptoms. Majority of the participants believed that MERS-CoV may lead to respiratory compromise (61%) and death (65%), while only 18% thought that there were no complications to MERS-CoV infection. Participants correctly believed that using a facemask (85.3%), hand washing (85.3%), using hand sanitizer (83.3%), avoiding contact with infected patients (82.4%), sneezing into a tissue (82.6%), and avoiding touching eyes and nose (76%) could prevent MERS-CoV transmission. However, participants generally appeared to have some misperceptions about the transmission of MERS-CoV. For instance, only 44% thought that animals (such as camels in MERS case) could transmit the disease and that it has been proven as a source of Coronavirus [Table 2].

Table 2.

Arab pilgrims' knowledge about Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

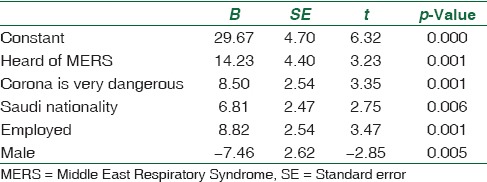

Table 3 shows the result of stepwise multiple linear regression that predicted factors significantly associated with the knowledge of MERS-CoV score. The factors associated with increased knowledge about MERS-CoV included Saudi nationality (β = 6.81, p = 0.006), respondents who perceived MERS-CoV included as very serious (β = 8.50, p = 0.001), participants who were employed (β = 8.82, p = 0.001), and participants who had heard about MERS-CoV (β = 14.23, p = 0.001). The MERS-CoV knowledge score was predicted to decrease by 7.64 for male participants (β= -7.64, p =0.005).

Table 3.

Predictors of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus knowledge according to stepwise regression analysis

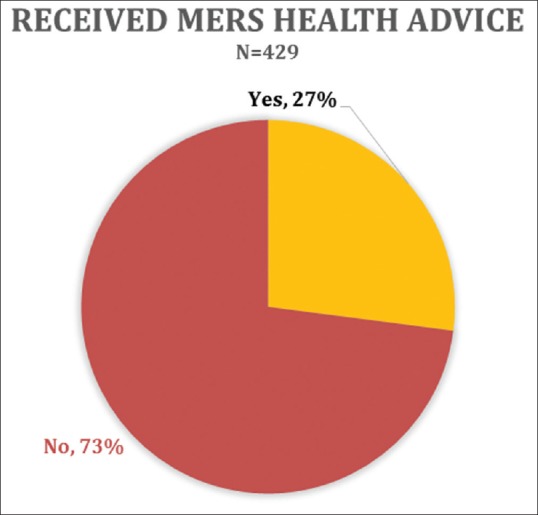

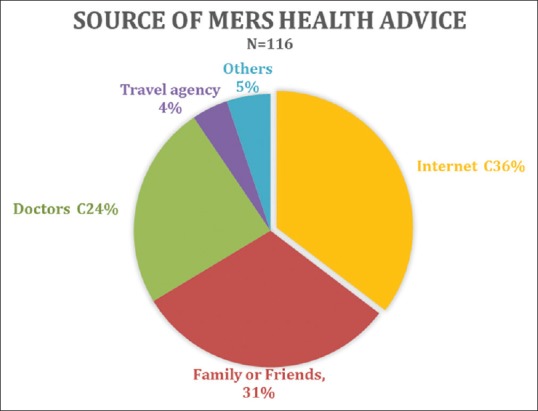

Only 27% the participants reported getting general health advice about MERS-CoV before coming to Makkah [Figure 1]. The sources of the advice about MERS-CoV were the internet (36%), friends or family (31%), doctors (28%), travel agency (4%), and remaining 5% from other sources [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Did person receive advice about Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus?

Figure 2.

Source of advice about Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

Discussion

This study provides descriptive information on Arab pilgrims' knowledge about MERS-CoV. Although our results cannot be generalized to cover all Makkah pilgrims, it reveals that non-Saudi Arabs are less aware of the ongoing situation with regard to MERS-CoV in Saudi Arabia than Saudis. This could be explained by the fact that since almost 80% of the confirmed cases are within the KSA, the local media have put a lot of effort into educating the Saudi society about MERS.

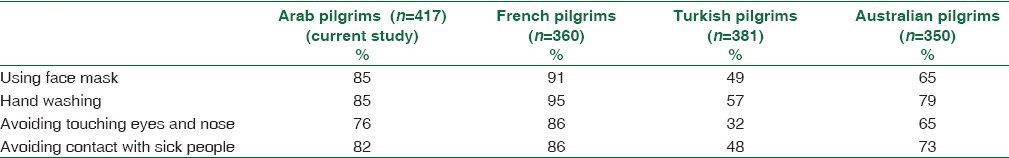

As Saudi Arabia becomes a well-known source of MERS-CoV, public awareness should be raised without creating panic, especially during mass gatherings such as the Hajj and Umrah.[7] With the absence of MERS-CoV vaccinations and treatment, public knowledge, awareness, and perception remains the cornerstone for MERS-CoV prevention. Al-Qahtani et al. tested the knowledge, attitude, and perception of Australian pilgrims about Ebola virus by assessing the pilgrim's background and current knowledge about the Ebola virus. They found that almost all Hajj pilgrims were aware of the Ebola outbreak. There were factors that affected knowledge, such as age and level of education.[8] With regard to respiratory infections, there was a high level of awareness of their risks among pilgrims and different preventive precautionary measures. Unfortunately, the use of face masks was uncommon among pilgrims, with only half of the pilgrims using the face masks because of many barriers, such as discomfort, breathing difficulty, and the feeling of isolation.[8,9] About 83% of our participants agreed that the use of face mask was helpful in decreasing the risk of MERS-CoV, but the percentage of use was not quantified. However, the effectiveness of face masks in decreasing the incidence of influenza-like illnesses in mass gatherings has been recently proven.[10] Health education programs have been proven to enhance pilgrim's knowledge of illnesses as well.[11] Another study conducted in France revealed that pilgrims from southern France were unaware of MERS-CoV before they consulted a specialized travel clinic.[12] One of the preventive measures to which almost all pilgrims adhered was hand hygiene.[8,13] The majority of study participants (85.3%) believed this measure to be helpful in preventing infection by the virus [Table 4]. The three most important protective behaviors shown to reduce the risk of transmission of respiratory illness were social distancing, hand hygiene, and contact avoidance.[14] About 82% of the respondents perceived that avoiding contact with sick people was a factor that would decrease transmission of the disease. Health promotion programs and the distribution of free face masks would increase their use dramatically.[15]

Table 4.

Comparison of pilgrim's knowledge about preventive measures against MERS reported by different studies

The Saudi Ministry of Health (MoH) annually publishes recommendations for pilgrims, including special advice for the elderly, children, pregnant women, and those with chronic diseases to preferably postpone their travel to Makkah. Those who would still like to travel are advised to take the utmost precautions. However, many pilgrims were not aware of MERS-CoV infection in Saudi Arabia and its preventive measures. For instance, a study conducted in France in pre-Hajj outpatient clinics for French Hajj pilgrims on MERS-CoV and its prevention showed that only 64.3% of the study participants were aware of MERS-CoV, and only 35.5% were aware of the recommendations by the Saudi MoH.[12] Another study among Australian pilgrims showed that only about 49% of the pilgrims were familiar with MERS-CoV.[11] This figure is slightly close to another survey of Turkish pilgrims which found that 56% were aware of this virus.[16] However, these numbers are quite different from our study that targeted Arab pilgrims, which showed that 91% had heard of MERS-CoV.

The lack of awareness of MERS-CoV, a potentially serious infection, among the pilgrims especially during Ramadan and Hajj, indicates that the health authorities in the pilgrims' countries of origin should be more active in promoting health education and awareness, especially in the absence of an effective treatment or vaccine for MERS-CoV. A visit to Makkah requires that pilgrims obtain a visa and take meningococcal vaccine. Perhaps it should be mandatory to also provide educational material on the risks of CoV and possible preventive measures.

Limitations

First, the sample size represented a relatively small percentage of the total number of pilgrims that performed Umrah during Ramadan in 2015. Furthermore, since we used nonprobability sample of convenience, the results cannot be generalized to all the pilgrims. Second, some data were missing probably as a result of the use of self-administered questionnaire. This might have restricted the external validations of our study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the College of Medicine and Research Center, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. ALL the authors are grateful to KSU Life Club volunteers for their help in collecting the data.

References

- 1.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balkhair A, Alawi FB, Al Maamari K, Al Muharrmi Z, Ahmed O. MERS-CoV: Bridging the knowledge gaps. Oman Med J. 2014;29:169–71. doi: 10.5001/omj.2014.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saad M, Omrani AS, Baig K, Bahloul A, Elzein F, Matin MA, et al. Clinical aspects and outcomes of 70 patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: A single-center experience in Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;29:301–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soliman T, Cook AR, Coker RJ. Pilgrims and MERS-CoV: What's the risk? Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2015;12:3. doi: 10.1186/s12982-015-0025-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan K, Sears J, Hu VW, Brownstein JS, Hay S, Kossowsky D, et al. Potential for the international spread of middle East respiratory syndrome in association with mass gatherings in Saudi Arabia. PLoS Curr. 2013;5 doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.a7b70897ac2fa4f79b59f90d24c860b8. pii: Ecurrents.outbreaks.a7b70897ac2fa4f79b59f90d24c860b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abubakar I, Gautret P, Brunette GW, Blumberg L, Johnson D, Poumerol G, et al. Global perspectives for prevention of infectious diseases associated with mass gatherings. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:66–74. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Turki YA. Can we increase public awareness without creating anxiety about corona viruses? Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:286–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alqahtani AS, Wiley KE, Willaby HW, BinDhim NF, Tashani M, Heywood AE, et al. Australian Hajj pilgrims' knowledge, attitude and perception about Ebola, November 2014 to February 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015;20:pii: 21072. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.12.21072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alqahtani AS, Sheikh M, Wiley K, Heywood AE. Australian Hajj pilgrims' infection control beliefs and practices: Insight with implications for public health approaches. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2015;13:329–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, Barasheed O, Rashid H, Booy R, El Bashir H, Haworth E, et al. A cluster-randomised controlled trial to test the efficacy of facemasks in preventing respiratory viral infection among Hajj pilgrims. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2015;5:181–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alqahtani AS, Wiley KE, Tashani M, Heywood AE, Willaby HW, BinDhim NF, et al. Camel exposure and knowledge about MERS-CoV among Australian Hajj pilgrims in 2014. Virol Sin. 2016;31:89–93. doi: 10.1007/s12250-015-3669-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gautret P, Benkouiten S, Salaheddine I, Belhouchat K, Drali T, Parola P, et al. Hajj pilgrims knowledge about Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, August to September 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20604. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.41.20604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gautret P, Soula G, Parola P, Brouqui P. Hajj pilgrims' knowledge about acute respiratory infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1861–2. doi: 10.3201/eid1511.090201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balaban V, Stauffer WM, Hammad A, Afgarshe M, Abd-Alla M, Ahmed Q, et al. Protective practices and respiratory illness among US travelers to the 2009 Hajj. J Travel Med. 2012;19:163–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2012.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benkouiten S, Brouqui P, Gautret P. Non-pharmaceutical interventions for the prevention of respiratory tract infections during Hajj pilgrimage. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2014;12:429–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahin MK, Aker S, Kaynar Tuncel E. Knowledge, attitudes and practices concerning Middle East respiratory syndrome among Umrah and Hajj pilgrims in Samsun, Turkey, 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015;20:pii=30023. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.38.30023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]