Abstract

The Communication Play Protocol (CPP) is a semi-naturalistic, lab-based observational procedure that showcases parent-child interactions. This article reflects on how the CPP has matured since we described it over 25 years ago in the May 1999 issue of Perspectives. We emphasize how the CPP has provided us with a stable frame to observe both typically developing children and children with developmental challenges including autism spectrum disorder as they communicate with caregivers in a range of contexts. We also describe three versions of the CPP that have been designed to address different research questions and several methods including engagement state coding and rating items that have been used to extract data from video records of the CPP. We conclude that the CPP can provide both researchers and clinicians with a valuable way to systematically capture variations in language development.

Researchers all too rarely have the opportunity to revisit their previous claims about the potential of a new research method. Thus it was with gratitude and not a small bit of trepidation that we readily agreed when Gail Van Tatenhove asked us to write a “contemporary version” of our “historical article,” Viewing Variations in Language Development, The Communication Play Protocol, which appeared in the May 1999 issue of the SIG 12 newsletter. Our aim there was to describe a new semi-naturalistic, lab-based observational procedure, the Communication Play Protocol (CPP; Adamson & Bakeman, 1999) that produces a “Play” rich with scenes of parent-child interactions. Often encountered in our literature are procedures for observing interactions that ask a parent to “play as usual” with objects (e.g., “free play” in Bakeman & Adamson, 1984; the “three bags task” in Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015). The essence of the CPP—and what differentiates it from other procedures—is the CPP’s extended use of the simple metaphor of a play. As we explained in our previous note (Adamson & Bakeman, 1999):

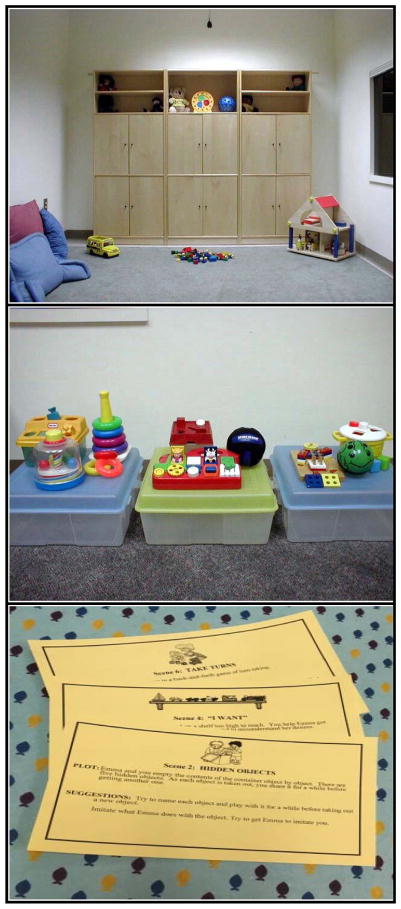

…We use this metaphor liberally as we tell a caregiver verbally and in writing what it is that we want her to do. Our main image is that her child will “star” in “a play” whose major theme is current ways of communicating. We ask her to be the “co-star,” and we note that she is essential because her child would be far less able to perform if anyone else took this role. Then, we proceed to direct the CPP on a “stage” that is a playroom which has one way mirrors so that the “actors” can perform each scene with the audience (two video cameras) hidden from view. [see Figure 1]

From the caregiver’s perspective, the ensuing play consists of eight 5-minute “Interactive Scenes” during which she engages with her child to enact a specified “plot” using “props” that we provide. We do not provide a script but we do give the mother a “cue card” at the beginning of each scene that specifies the plot, props, and directional suggestions. Between each scene, the director enters the stage, provides new props and a cue card, and rapidly exits. (p. 3)

Figure 1.

The Communication Play’s Stage (top), Props (middle), and Cue Cards (bottom).

When we wrote our original article, we had produced 200 Plays. Although we had yet to complete a study that used the CPP, we were confident that “the plays provide varied views of communication, including moments of tense drama and endearing comedy, which caregivers indicate are accurate records of the child’s current ways of communicating” (pp. 3–4). Now, with the passage of time and continuous support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, we are still using the CPP to study variations in early communication. Our research team has recorded literally thousands of Plays, published several articles using data derived from their video records, and shared the CPP manual and associated technical reports (available upon request) with colleagues across the globe.

There are many reasons we like to use the CPP. High among them is that caregivers and children—including typically developing toddlers and young children with developmental difficulties including autism spectrum disorder and severe speech delays—almost always enjoy performing the CPP. Thus our observation sessions are almost always complete and attrition rates in our longitudinal studies are low. We think the procedure is well accepted because it assigns parents an active role without leaving them puzzled about what we expect of them and their children.

From our perspective as researchers, we especially like how the CPP provides a stable frame—a series of scenes—to observe how a child communicates in a range of contexts. There are three reasons why we find viewing interactions using this frame illuminating. First, the CPP captures current communication patterns in a relatively brief session. By concentrating on a range of common communication functions, it can serve as a valuable complement to extended home observations that use video or audio recordings to sample the child’s natural language environment. Moreover, it can supplement standardized language and communication assessments that probe specific functions (e.g., Dunn & Dunn, 2007, Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test; Mundy, Delgado, & Hogan, 2003, Early Social Communication Scales) or level of skill (e.g., Mullen, 1995, Mullen Scales of Early Learning) as the child interacts with a well-scripted friendly stranger.

The second reason we like viewing a series of scenes is that it divides an observation session into smaller well-defined but functionally meaningful units. Our original CPP contained eight 5-minute scenes; there were two scenes designed to display four communicative functions (social interacting, requesting, commenting, and narrating) using “every day” plots such as making music or looking at pictures together (see Table 1). This not only provides a structure easily understood by our players, but also has several methodological advantages. For example, we know up front that children will spend the same amount of time in different communicative conditions, so we do not have to compensate for variations across dyads in how much time they devoted to one condition compared to another. In addition, we can randomize the order of conditions so that when it comes time to interpret findings related to conditions we are not forced to consider the possibility that the findings merely reflect some uninteresting third variable such as increasing fatigue as the session progressed.

Table 1.

Plots for the Scenes in Three Versions of the Communication Play Protocol

| Communicative context | Plots | Original CPP | CPP-2 | CPP-A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social interacting | Take turns | x | x | |

| Play music | x | |||

| Requesting | I want that toy on the shelf | x | x | |

| Help me play with a toy | x | |||

| Commenting | What’s in the container | x | x | |

| Visit to the art gallery | x | |||

| Narrating time | Discuss the past | x | x | |

| Discuss the future | x | x | ||

| Internal states | What others desire | x | ||

| What others believe | x | |||

| Graphic systems | Writing | x | ||

| Drawing | x | |||

| Sounds | The child’s name | x | ||

| Music (piano or cello) | x | |||

| Animal (bird or cat) | x | |||

| Mechanical (train or motorcycle) | x |

Third, and most importantly, new Plays can be tailored to fit research questions and samples by changing scenes rather than retooling the entire data collection structure. We have used this strategy often in our research program. Initially we (Adamson, Bakeman, & Deckner, 2004) designed a Play suited to studying how symbol-infused joint engagement typically develops as language emerges between 18- and 30-months of age. Then, when we began observing joint engagement in young children with autism and with Down syndrome (Adamson, Bakeman, Deckner, & Romski, 2009), and in young children whose language was severely delayed (Adamson, Romski, Bakeman, & Sevcik, 2010), we decided to shorten the Play to 6 scenes; we dropped the two scenes (“past” and “future”) in the more language-dependent narrating context because many of the participants were minimally verbal. This 6-scene version became standard fare in our next large longitudinal study of the development of children at risk for autism (e.g., Suma, Adamson, Bakeman, & Robins, 2014). Later, when we wanted to observe how interactions developed into conversations (Adamson, Bakeman, Deckner, & Nelson, 2014) by following the typically-developing children we had started to observe when they were 18 months old until they were 5½ years old, we again modified the Play (calling it now the CPP-2). To make the scenes more interesting for our more mature participants and to observe more fully the complexity of symbol use, we retained only the two narrating scenes about time and added four new ones that focused on discussion of internal states and the use of graphic systems (see Table 1). And now, in our fourth cycle of studies of joint engagement using the CPP, we are using a version of the CPP (which we call the Communication Play Protocol-Auditory or CPP-A; see Table 1) that contains three scenes from our standard version and four new scenes that probe variations in how children and caregivers shared sounds both developmentally from 12 to 30 months of age and between groups of 2-year olds who are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and with other developmental disorders.

Perhaps the biggest challenge presented by the CPP is that it does not, in and of itself, produce data. Unlike standardized assessments and automated devices, extracting data from video records takes hours (and hours) of coders’ time. This arduous process can be guided by knowledge of systematic observational methods (Bakeman & Quera, 2011) and eased by using computer programs such as Mangold International’s INTERACT (http://www.mangold-international.com) or similar computer programs for assisting the coding of video records. In our studies, we have made transcripts (e.g., Adamson & Bakeman, 2006), done state coding (Adamson et al., 2004, 2009; Adamson, Deckner, et al., 2010, Adamson, Romski, et al., 2010), used rating items (Adamson, Bakeman, Deckner, & Nelson, 2012; Suma et al., 2014), and focused on specific events such as children’s gestures (Özçalışkan, Adamson, & Dimitrova, 2015).

There is, we admit, a temptation to code more details about behavior than we might need to answer a specific research question. But sometimes less is not only fine but also actually more informative. Recently we (Adamson et al., 2012) directly compared results from our earlier (Adamson et al., 2009) findings about the development of symbol-infused joint engagement obtained using state coding with results using rating items. A major advantage of rating is that it takes considerably less time than coding: a trained rater can rate a 5 min scene in 15 min while a trained coder might take an hour. For the purpose of measuring the amount of various types of joint engagement during caregiver-child interactions, we found that ratings generated almost identical results to coding, both when we compared groups of children and the same children at two-age points. Moreover, given the efficiency of using rating items, we were able to expand our data capture to include several more aspects of the child’s behavior (e.g., a rating of expressive language), the caregiver’s behavior (e.g., scaffolding and following in on the child’s focus), and the dyad’s interaction (e.g., its fluency and connectedness).

It is easier to use a relatively streamlined coding scheme be more parsimonious initially knowing that the video records remain available for additional coding later. We have revisited our growing archive of Plays several times. Sometimes we looked only at a specific scene (e.g., Nelson, Adamson, & Bakeman, 2012, focused on the Belief scene in the CPP-2) or examined a specific behavior (e.g., Özçalışkan, Adamson, Dimitrova, Bailey, & Smuck, 2015, documented the use of baby signs as toddlers request and comment). Or, we documented how autism spectrum disorder and Down syndrome influence a specific communication process (e.g., Adamson, Bakeman, & Brandon, 2015, considered how parents introduce novel words to young children and Dimitrova, Özçalışkan, & Adamson, 2016, considered how parents’ translations of children’s gestures facilitate vocabulary acquisition). Sometimes our archive helped a colleague answer a research question (e.g., Visootsak, Hess, Bakeman, & Adamson, 2013, on the effects of congenital heart defects on the language development of young children with Down syndrome). Much to our delight, sometimes we see something new hidden in the structure of the Play, as we did when we focused on the interlude between scenes to probe how variations in children’s interests might affect their engagement during parent-child interactions (Adamson, Deckner, & Bakeman, 2010).

One take-home message is that CPP video records are a valuable research resource and so it is important to consider not only how to produce them but also how to save them. As cameras become cheaper and smaller, capturing more views becomes feasible (e.g., in our current study, we are supplementing the two-camera view we have used for many years with a small head cam worn by the caregiver). And as vast digital storage becomes available at little cost, barriers to recording not just many views but many hours are crumbling (although a possible downside is the need to convert older media such as tapes and DVDs into digital files). Vast digital storage has its challenges, including management of files, their maintenance and backup, but also—once relevant ethical concerns have been satisfactorily addressed—the potential for sharing. One promising possibility is that video records may be preserved and shared in Databrary (https://nyu.databrary.org), a shared archive for developmental science.

The CPP was developed as a research tool for studies of communication development. But clinicians may also find that it is a useful procedure for collecting systematic observations that can help retain a record of a child’s communication with a parent before, during, and following an intervention. As in a research study, its use can provide a stable frame for repeated observations that are far more nuanced than observations of “free play”. Designing a Play can help a clinician decide what to monitor closely over the course of an intervention. For example, a Play with scenes focused on requesting and commenting might be produced just before and at various intervals after a new AAC device is provided to see if the device facilities the child’s use of these important communication functions. Props might be selected to include objects that correspond to vocabulary available on the device. Directorial suggestions might encourage the parent to display a newly learned strategy such as demonstrating the use of the device or waiting for the child to initiate its use. Moreover, using the metaphor of a Play may help engage a parent in the production of interactions. Further, reviewing the video records of Plays produced at different points in an intervention with the parent might facilitate discussions about the child’s communication progress and challenges and about the next steps in the intervention.

Pausing to compose a contemporary version of our earlier comments about the Communication Play Protocol has reinforced our conviction that it is a semi-naturalistic data collection procedure that “can provide us, both as researchers and clinicians, a view of the rich variation in early communicative development” (Adamson & Bakeman, 1999, p. 4). We are especially heartened that it can help us capture established patterns of a child’s interaction with a caregiver who is a critical partner in language acquisition. This exercise has also prompted us to reflect on how we hope the CPP will fare in the future. Needless-to-say, we expect that we will be modifying and using the CPP in our own studies of processes and differences in language development. In addition to our current project about auditory joint engagement and language development, we plan to work with colleagues to adapt the CPP to study the effectiveness of early ASD interventions and to assess the effectiveness of community-based interventions that seek to strengthen the communication foundation for language development in children from low-income families. More broadly, we hope that some of the CPP’s more unusual nuances—such as its use of metaphor to communicate with caregivers—will inspire others to collect systematic observations of parent-child interactions. Further, and perhaps most fervently, we hope that the CPP serves as a well-honed example of the benefits of how best to structure observations of children’s communication before we turn the video cameras on. The productivity and usefulness of all subsequent coding and analysis of our video records rests crucially on well-considered data collection strategies.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the development of the Communication Play Protocol was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD035612. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R. Viewing variations in language development: The communication play protocol. Perspectives on Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 1999;8:2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R. The development of displaced speech in early mother-child conversations. Child Development. 2006;77:186–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Brandon B. How parents introduce new words to young children: The influence of development and developmental disorders. Infant Behavior and Development. 2015;39:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Deckner DF. The development of symbol-infused joint engagement. Child Development. 2004;75:1171–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Deckner DF, Nelson PB. Rating parent-child interactions: Joint engagement, communication dynamics, and shared topics in autism, Down syndrome, and typical development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42:2622–2635. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1520-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Deckner DF, Nelson PB. From interactions to conversations: The development of joint engagement during early childhood. Child Development. 2014;85:941–955. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Deckner DF, Romski M. Joint engagement and the emergence of language in children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:84–96. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0601-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson LB, Deckner DF, Bakeman R. Early interests and joint engagement in typical development, autism, and Down syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40:665–676. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0914-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson LB, Romski MA, Bakeman R, Sevcik RA. Augmented language intervention and the emergence of symbol-infused joint engagement. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2010;53:1769–1773. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0208). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Adamson LB. Coordinating attention to people and objects in mother-infant and peer-infant interaction. Child Development. 1984;55:1278–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Quera V. Sequential analysis and observational methods for the behavioral sciences. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova N, Özçalıskan S, Adamson LB. Parents’ translations of child gesture facilitate word learning in children with autism, Down syndrome and typical development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46:221–231. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2566-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn DM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. 4. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson Assessments; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh-Pasek K, Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Owen MT, Golinkoff RM, Pace A, Yust PKS, Suma K. The contribution of early communication quality to low-income children’s language success. Psychological Science. 2015;26:1071–1083. doi: 10.1177/0956797615581493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen EM. Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Pline, MN: American Guidance Circle; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mundy P, Delgado C, Hogan A. A manual for the abridged Early Social Communication Scales (ESCS) Department of Psychology, University of Miami; Miami, FL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PB, Adamson LB, Bakeman R. The developmental progression of understanding of mind during a hiding game. Social Development. 2012;21:313–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçalışkan S, Adamson LB, Dimitrova N. Early deictic but not other gestures predict later vocabulary in both typical development and autism. Autism. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1362361315605921. on-line. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçalışkan S, Adamson LB, Dimitrova N, Bailey J, Schmuck L. Baby sign but not spontaneous gesture predicts later vocabulary in children with Down syndrome. Journal of Child Language. 2015 doi: 10.1017/S030500091500029X. on-line. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suma K, Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Robins DL. The impact of early intervention on parent-child communication following early ASD screening. Poster presented at the International Meeting for Autism Research; Atlanta. May, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Visootsak J, Hess B, Bakeman R, Adamson LB. Effect of congenital heart defects on language development of toddlers with Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2013;57:887–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]