Abstract

Background:

We systematically reviewed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of complementary and alternative interventions for fatigue after traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Methods:

We searched multiple online sources including ClinicalTrials.gov, the Cochrane Library database, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, the Web of Science, AMED, PsychINFO, Toxline, ProQuest Digital Dissertations, PEDro, PsycBite, and the World Health Organization (WHO) trial registry, in addition to hand searching of grey literature. The methodological quality of each included study was assessed using the Jadad scale, and the quality of evidence was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system. A descriptive review was performed.

Results:

Ten RCTs of interventions for post-TBI fatigue (PTBIF) that included 10 types of complementary and alternative interventions were assessed in our study. There were four types of physical interventions including aquatic physical activity, fitness-center-based exercise, Tai Chi, and aerobic training. The three types of cognitive and behavioral interventions (CBIs) were cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), and computerized working-memory training. The Flexyx Neurotherapy System (FNS) and cranial electrotherapy were the two types of biofeedback therapy, and finally, one type of light therapy was included. Although the four types of intervention included aquatic physical activity, MBSR, computerized working-memory training and blue-light therapy showed unequivocally effective results, the quality of evidence was low/very low according to the GRADE system.

Conclusions:

The present systematic review of existing RCTs suggests that aquatic physical activity, MBSR, computerized working-memory training, and blue-light therapy may be beneficial treatments for PTBIF. Due to the many flaws and limitations in these studies, further controlled trials using these interventions for PTBIF are necessary.

Keywords: complementary and alternative medicine, fatigue, intervention, systematic review, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Fatigue is a common phenomenon following traumatic brain injury (TBI), with a reported prevalence ranging from 21% to 80% [Ouellet and Morin, 2006; Bushnik et al. 2007; Dijkers and Bushnik, 2008; Cantor et al. 2012; Ponsford et al. 2012], regardless of TBI severity [Ouellet and Morin, 2006; Ponsford et al. 2012]. Post-TBI fatigue (PTBIF) refers to fatigue that occurs secondary to TBI, which is generally viewed as a manifestation of ‘central fatigue’. Associated PTBIF symptoms include mental or physical exhaustion and inability to perform voluntary activities, and can be accompanied by cognitive dysfunction, sensory overstimulation, pain, and sleepiness [Cantor et al. 2013]. PTBIF appears to be persistent, affects most TBI patients daily, negatively impacts quality of life, and decreases life satisfaction [Olver et al. 1996; Cantor et al. 2008, 2012; Bay and De-Leon, 2010]. Given the ubiquitous presence of PTBIF, treatment or management of fatigue is important to improve the patient’s quality of life after TBI. However, the effectiveness of currently available treatments is limited.

Although pharmacological interventions such as piracetam, creatine, monoaminergic stabilizer OSU6162, and methylphenidate can alleviate fatigue, adverse effects limit their usage and further research is needed to clarify their effects [Hakkarainen and Hakamies, 1978; Sakellaris et al. 2008; Johansson et al. 2012b, 2014]. Therefore, many researchers have attempted to identify complementary and alternative interventions to relieve PTBIF [Bateman et al. 2001; Hodgson et al. 2005; Gemmell and Leathem, 2006; Hassett et al. 2009; Johansson et al. 2012a; Björkdahl et al. 2013; Sinclair et al. 2014]. In this study, we aimed to systematically review randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated treatment of PTBIF using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) to provide practical recommendations for this syndrome.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We performed online searches using multiple sources, including ClinicalTrials.gov, the Cochrane Library database, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, the Web of Science, AMED, PsychINFO, Toxline, ProQuest Digital Dissertations, PEDro, PsycBite, and the World Health Organization (WHO) trial registry, in addition to hand searching of grey literature. The last search was performed on May 10, 2016. Search terms included TBI, head injury, head trauma, and brain injury; or brain trauma, concussion, fatigue, and tiredness. The reference lists of all retrieved studies and relevant reviews were searched manually to identify additional trials missed by the electronic literature search. G.X. and M.W. initially screened and included all articles based on the title and abstract. Full-text articles were obtained for all eligible studies and were assessed independently by G.X. and Y.L. against the inclusion and exclusion checklist. Disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached; if this failed, a third party, D.C., was consulted. All RCTs investigating the effect of complementary and alternative interventions on fatigue management in patients with TBI were included, regardless of intervention type. The inclusion criteria were: (1) studies that were RCTs or randomized crossover trials; (2) articles written in English and published or informally published; and (3) studies that compared interventions with a placebo intervention, no treatment, or other types of interventions. The exclusion criteria were: (1) nonrandomized studies; (2) studies that lacked outcome measures for fatigue; and (3) studies testing pharmacological interventions, as well as botanical or herbal interventions.

Outcome measures

The outcome of this study was any symptom of fatigue or tiredness, as evaluated by a range of current valid and reliable indices such as the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) [Krupp et al. 1989], Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS) [Fisk et al. 1994], Mental Fatigue Scale (MFS) [Johansson et al. 2009], and Profile of Mood States (POMS) [Shahid et al. 2012]. While there are many measures and instruments of fatigue with acceptable psychometric properties, there is not yet a ‘gold standard’ measure of fatigue due to clinical overlap between fatigue, depression, sleepiness, and other conditions.

Evaluation of quality of evidence

The methodological quality of each included study was assessed using the Jadad scale, based on the description of randomization, blinding, and patient attrition. Higher scores indicate better quality [Jadad et al. 1996]. The quality of evidence was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system [Balshem et al. 2011].

Data extraction

Data were extracted and independently crosschecked using a standard data extraction form. For each study, the types of interventions and detailed patient characteristics were extracted, as well as relevant fatigue outcome data.

Data analysis

For continuous outcomes, a weighted mean difference was calculated. In the presence of heterogeneity, we explored potential clinical, methodological and statistical sources. Because interstudy heterogeneity precluded a meta-analysis, a narrative synthesis of all of the included studies was employed.

Results

Search results

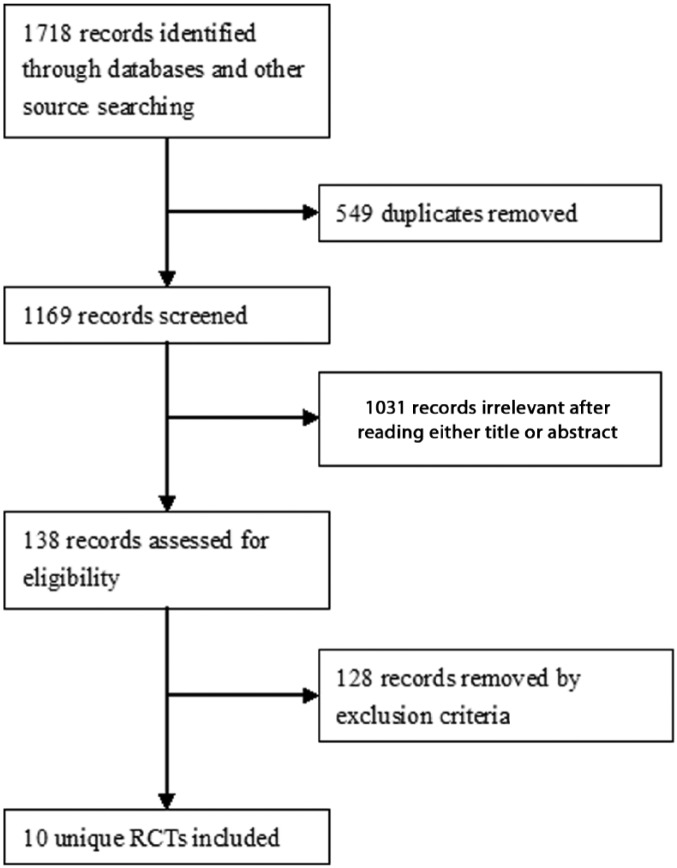

The study selection process is shown in Figure 1. A total of 1718 records were identified from searches. Ultimately, 10 unique RCTs that met the inclusion criteria were included in the review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The study selection process for the systematic review.

Characteristics of the included randomized controlled trials

Details of the included trials are summarized in Table 1. The interventions and outcome measures varied between studies, indicating apparent clinical heterogeneity. There were 10 different types of interventions in the 10 included trials. In addition, because of the heterogeneity in population characteristics, intervention types, outcome measures and durations of intervention, it was not considered appropriate to perform a meta-analysis to provide a pooled estimate of the outcome measure. Therefore, narrative analysis rather than meta-analysis was employed. Among these interventions, there were four types of physical interventions: fitness-center-based exercise [Hassett et al. 2009], Tai Chi [Gemmell and Leathem, 2006], aquatic physical activity [Dijkers and Bushnik, 2008], and aerobic training [Bateman et al. 2001]. The three types of cognitive and behavioral interventions (CBIs) were cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [Hodgson et al. 2005], mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) [Johansson et al. 2012a], and computerized working-memory training [Björkdahl et al. 2013]. The two types of biofeedback therapy were the Flexyx Neurotherapy System (FNS) [Schoenberger et al. 2001] and cranial electrotherapy [Smith et al. 1994], and blue-light therapy was the only included light therapy [Sinclair et al. 2014].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies and quality of the evidence included in the systematic review.

| Study | Country | Participants’ type of disease | Sample size | Design | Trial duration | Interventions description | Outcomes assessed | Results | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith et al. [1994] | USA | CHI | 21 | RCT (parallel) | 3 weeks | IG: Cranial electrotherapy stimulation 45-minute sessions, 4 days per week × 3 weeks (12 sessions) (n = 10) CG1: sham-treated (n = 5) CG2: placebo (n = 6) |

POMS Fatigue | Fatigue/inertia scores significant lower in IG (pretest, Mn = 7.44, SD = 6.75 versus post-test, Mn = 0.33, SD = 0.96, p value was not stated). | ⊕⊕OO Low |

| Bateman et al. [2001] | England | TBI (44), stroke (70), SAH (15) or other (28) | 157 | RCT (parallel) | 24 weeks | IG: aerobic training (n = 78) CG: relaxation training (n = 79) |

Fatigue scale | The fatigue questionnaire scores had no significance in (group × time) interactions in ANOVA. | ⊕⊕OO Low |

| Schoenberger et al. [2001] | USA | TBI | 12 | RCT (WLC) | 20 weeks | IG: immediate FNS treatment (n = 6) CG: WLC group (n = 6) |

MFI | No significant in MFI total score (p < 0.09), but General Fatigue (p < 0.02) and Mental Fatigue (p < 0.02) subscales were significantly improved in IG compared with CG. No significant difference for Physical Fatigue (p < 0.13) | ⊕OOO Very low |

| Hodgson et al. [2005] | Australia | CHI (9), stroke (1), hypoxic brain injury (1), cerebral oedema (1) | 12 | RCT (WLC) | 13-18 weeks | IG: 9 to 14 individual 1 hour, weekly sessions of CBT (n = 6) CG: WLC group (n = 6) |

POMS fatigue–inertia subscale | No statistical significance for main or interaction effects for fatigue, but effect sizes postintervention and at 1-month follow up were medium (0.4) | ⊕OOOVery low |

| Gemmell et al. [2006] | New Zealand | TBI | 18 | RCT (WLC) | 9 weeks | IG: Tai Chi twice weekly for 45 minutes, 6 weeks (n = 9) CG: WLC group (n = 9) |

VAMS tiredness item | No significant difference between groups in vitality (fatigue) (before and after intervention, 54.42 ± 6.03 versus 52.52 ± 5.82, t = 1.104, p value was not stated) | ⊕OOOVery low |

| Driver et al. [2009] | USA | TBI | 16 | RCT (parallel) | 8 weeks | IG: 3 × 1-hour sessions/week x 8 weeks aquatic physical activity, both aerobic & resistance (n = 8) CG: 3 × 1-hour sessions/week x 8 weeks vocational readiness training (n = 8) |

POMS fatigue subscale | In IG, improvement from pre- to postintervention was found on the fatigue subscale of the POMS (p < 0.05, ES = 0.00), but there was no significant change in CG (ES = 0.08) | ⊕OOO Very low |

| Hassett et al. [2009] | Australia | TBI | 62 | RCT (parallel) | 6 months | IG: combined fitness and strength-training exercise in fitness center supported by on-site personal trainer (n = 32) CG: similar exercise programme unsupervised at home (n = 30) |

POMS Fatigue subscale | No difference in fatigue between two groups (p = 0.070 at 3 months (end of intervention), p = 0.178 at 6 months (3 months after the intervention ended) | ⊕OOOVery low |

| Johansson et al. [2012a] | Sweden | TBI (11) or stroke (18) | 29 | RCT (WLC) | 8 weeks | IG (MBSR group 1): MBSR (n = 15) CG (MBSR group 2): WLC group (n = 14) |

MFS | Statistically significant improvement was achieved in IG in the self-assessment for mental fatigue (F = 8.47, p = 0.008) | ⊕OOOVery low |

| Björkdahl et al. [2013] | Sweden | TBI (5), stroke (28) or other (5) | 38 | RCT (parallel) | 24 weeks | IG: standard rehabilitation + computerized working-memory training (n = 20) CG: standard rehabilitation (n = 18) |

FIS | Significant improvement in the FIS score in IG (p = 0.038, r = −0.33) | ⊕OOOVery low |

| Sinclair et al. [2014] | Australia | TBI | 30 | RCT (parallel) | 10 weeks | IG1: blue-light therapy 45 minutes/day, 4 weeks (n = 10) IG2: yellow-light therapy (n = 10) CG: no treatment control (n = 10) |

FSS | The blue-light group showed a significant improvement in fatigue compared to CG (difference from CG in quadratic time coefficient 0.04, p < 0.001). | ⊕OOO Very low |

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; CHI, closed-head-injured; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; CG, control group; ES, effect sizes; FIS, Fatigue Impact Scale; FSS, Fatigue Severity Scale; FNS, Flexyx Neurotherapy System; IG, intervention group; Mn, mean; MFS, Mental Fatigue Scale; MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction; MFI, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory; POMS, Profile of Mood States; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; TBI, traumatic brain injury; VAMS, Visual Analog Mood Scale; WLC, wait-list control.

Quality evaluation

A summary of quality assessment scores for the included trials is shown in Table 2. Of the 10 RCTs, only three studies were high-quality RCTs (3–5 points) based on the Jadad scale [Smith et al. 1994; Bateman et al. 2001; Hodgson et al. 2005], and the other studies were low-quality RCTs (0–2 points) [Schoenberger et al. 2001; Gemmell and Leathem, 2006; Driver and Ede, 2009; Hassett et al. 2009; Johansson et al. 2012a; Björkdahl et al. 2013; Sinclair et al. 2014]. The quality of this evidence was judged to be low/very low using the GRADE system (Table 1). Risk of bias in study design, imprecision and indirectness was the most common reason for low grades, keeping in mind there was only one RCT trial for each intervention.

Table 2.

Jadad quality assessment scores for the included trials.

| Study ID | Type of intervention | Randomization (0–2 points) | Double blinding (0–2 points) | Withdrawals/dropouts (0–1 points) | Total score* (0–5 points) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith et al. [1994] | Cranial electrotherapy stimulation | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Bateman et al. [2001] | Aerobic training | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Schoenberger et al. [2001] | FNS | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hodgson et al. [2005] | CBT | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Gemmell and Leathem [2006] | Tai Chi | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Driver and Ede [2009] | Aquatic physical activity | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Hassett et al. [2009] | Combined fitness and strength training exercise | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Johansson et al. [2012a] | MBSR | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Björkdahl et al. [2013] | Computerized working memory training | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sinclair et al. [2014] | Blue light therapy | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; FNS, flexyx neurotherapy system; MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction;

0 = very poor; 5 = rigorous.

Reported effects of intervention

Physical interventions

Many different types of physical interventions are used in clinical settings. Physical exercise programs provide cognitive and functional benefits [Wischenka et al. 2016]. Driver and Ede conducted an 8-week aquatic physical activity intervention for patients after TBI and used a vocational rehabilitation class as a control. After assessing pre- and post-treatment symptoms using the fatigue subscale of the POMS, they found a significant improvement in the intervention group [IG, effect size (ES) = 1.00], while there was no significant change in the control group (CG, ES = 0.08) [Driver and Ede, 2009].

Fitness training is an intervention that can potentially reverse deconditioning. Hassett and colleagues compared cardiorespiratory fitness and psychosocial functioning effects between a supervised fitness-center-based exercise program and an unsupervised home-based exercise program in subjects with TBI in a multicenter study. There was no between-group difference in psychosocial functioning at the end of the intervention or at follow up, and no difference in fatigue was found between the two groups (p = 0.070 at 3 months; p = 0.178 at 6 months) [Hassett et al. 2009].

Tai Chi is a gentle stress-free exercise form that is characterized by soft flowing movements that can be practiced for health improvement. The effects of a 6-week Tai Chi course on individuals with TBI were investigated by Gemmell and Leathem. No significant difference was found in the intervention group in tiredness as assessed using the Visual Analog Mood Scale (VAMS) [Arruda et al. 1999], but data from the control group were not provided. The authors reported that no within-subject improvement in fatigue was found [Gemmell and Leathem, 2006].

Aerobic exercise has various health benefits, including improving cardiorespiratory fitness and psychological well-being. The impact of fitness training on inpatients with brain injuries was examined by Bateman and colleagues. They conducted an RCT with 157 total participants, including inpatients with TBI, stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and other brain injuries. The patients attended a 12-week aerobic training program or relaxation training as the control condition. Assessments were performed using a fatigue scale before and after the 12-week training program and during a follow-up assessment 12 weeks post-training. Their results indicated that patient fatigue questionnaire scores did not significantly improve after the aerobic training program [Bateman et al. 2001].

Cognitive and behavioral interventions

CBIs are psychotherapy approaches that teach patients the cognitive and behavioral competencies needed to function adaptively in their interpersonal and intrapersonal worlds [Heimberg, 2002]. The common CBIs used in clinical settings include cognitive restructuring, relaxation training, social skills training, MBSR, and computerized working-memory training. Hodgson and colleagues evaluated the efficacy of CBT for acquired brain injury. They selected a set of patients, the majority of whom had suffered a TBI. The intervention group received hour-long CBT sessions each time, once per week for 9–14 weeks, and the control group was waitlisted. CBT may potentially reduce fatigue, as there was a medium ES (0.4) [Hodgson et al. 2005].

An MBSR is an educational program to improve attention and cognitive flexibility, increase brain neuronal connectivity, and help individuals to better cope with their difficulties. It has been used to treat patients with a wide range of conditions, such as stress, depression, pain, and fatigue [Johansson et al. 2012a]. The effects of MBSR on PTBIF with 29 participants with stroke and TBI were evaluated recently. Fifteen individuals participated in an MBSR program for 8 weeks, while the other 14 individuals served as controls and received no active treatment, but they were offered MBSR treatment during the following 8 weeks. Participants who completed the MBSR program had a decline in self-assessed MFS score (p = 0.004), while control group scores remained unchanged over the 8 weeks (p = 0.89). There was a significant difference in MFS score between the two groups after the 8-week MBSR program (p = 0.008). The control group completed the MBSR program at a later stage and also showed similar and significant declines in MFS scores after 8 weeks of MBSR (p = 0.002) [Johansson et al. 2012a].

Björkdahl and colleagues investigated whether computerized working-memory training after brain injury had a significant effect on daily life functions. Both the intervention group and control group underwent a 5-week standard rehabilitation. In addition, the intervention group also received working-memory training. The FIS score in the intervention group improved significantly after working-memory training compared with pretraining, but the score in the control group did not significantly improve [Björkdahl et al. 2013].

Biofeedback therapy

Conventional electroencephalographic biofeedback has the potential to improve the cognitive symptoms and problematic behaviors. Schoenberger and colleagues evaluated the potential efficacy of the FNS, a type of electroencephalographic biofeedback, as treatment for TBI. In between-group comparisons, the intervention group exhibited significantly improved General Fatigue and Mental Fatigue subscale scores versus the control group, though the total Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) score did not change significantly [Schoenberger et al. 2001].

Cranial electrotherapy stimulation has been used to alleviate anxiety, depression and insomnia in clinical settings. Smith and colleagues assessed the effects of cranial electrotherapy stimulation (1.5 mA, 100 Hz, 45 min/day, 4 days/week for 3 weeks) on patients who suffered closed head injuries. Compared with both a sham treatment group and a no-treatment group, the treatment group showed significantly greater improvement on the Fatigue–Inertia scale of the POMS [Smith et al. 1994].

Light therapy

Light therapy can improve depressed mood and fatigue in patients with cancer. Sinclair and colleagues investigated the efficacy of 4 weeks (45 min/day) of blue-light therapy for fatigue reduction in patients with TBI and compared it with yellow light as a placebo and no treatment. Treatment with blue-light therapy significantly reduced fatigue by FSS score during the treatment phase. These changes were not observed in the groups that underwent yellow light therapy or no treatment. However, the authors indicated that improvements in these measures did not persist following cessation of the treatment at week 8 [Sinclair et al. 2014].

Side effects

Two of 10 included studies reported no side effects [Smith et al. 1994; Bateman et al. 2001], and three studies reported minor side effects, such as musculoskeletal pain for fitness training exercise and headache for blue-light therapy [Schoenberger et al. 2001; Hassett et al. 2009; Sinclair et al. 2014]. All adverse events resolved spontaneously and did not result in discontinuation of therapy. The other five studies lacked information regarding the side effects of CAM interventions [Hodgson et al. 2005; Gemmell and Leathem, 2006; Driver and Ede, 2009; Johansson et al. 2012a; Björkdahl et al. 2013].

Discussion

The objectives of this review were to systematically characterize and evaluate CAM studies for PTBIF. We have revealed the various CAM interventions explored to date for the treatment of PTBIF. There is evidence for the effectiveness of physical activity, MBSR, computerized working-memory training, and blue-light therapy for the treatment of PTBIF. However, these interventions must be used with caution in clinical practice because of the high risk of bias in most studies and the small number of studies for each intervention type. The quality of this evidence was judged to be low/very low using the GRADE system based on the risk of bias, imprecision and indirectness, and more important, there was only one RCT trial for each intervention.

CAM therapies are attractive because they use an integrative approach to healing and usually cause fewer side effects than drug treatment. In the 10 studies included in this review, two studies reported no side effects and three studies reported minor side effects, whereas five studies lacked information concerning side effects. In another systematic review there were only five studies among 26 included RCTs on CAM treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome that assessed the side effects of CAM treatment. The conclusion from those five studies also indicated that no severe side effects were found for CAM treatment. However, the side effects of CAM treatment should be assessed in future CAM trials, even though they are minimal [Alraek et al. 2011].

Despite the high occurrence and enduring nature of fatigue complaints after TBI and the trials using complementary and alternative interventions that show promising preliminary findings, the most effective strategies for PTBIF treatment are not yet established. A systematic review of the literature on fatigue management currently being undertaken suggests there are few high-quality studies on effective PTBIF interventions [Hicks et al. 2007]. While Cantor and colleagues previously conducted a systematic review of interventions for fatigue after TBI, they included both RCTs and non-RCTs [Cantor et al. 2014]. In the current study, we included only RCTs, with three new RCTs in addition to the seven RCTs in Cantor’s systematic review [Bateman et al. 2001; Johansson et al. 2012a; Björkdahl et al. 2013]. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of RCTs on complementary and alternative interventions for PTBIF. This study provides information regarding the knowledge of CAM interventions by evaluating the efficacy of CAM modalities when treating PTBIF.

The etiology of PTBIF is complex, as it is a multidimensional syndrome that includes physical, psychological, motivational, situational, and activity-related components [Lachapelle and Finlayson, 1998; Ouellet and Morin, 2006; Cantor et al. 2008]. Fatigue management guidelines compiled by Mock [Mock, 2001] include coping strategies, cause-specific interventions, pharmacologic interventions, and nonpharmacologic interventions such as exercise, nutrition, sleep therapy, and restorative therapy.

For physical and cognitive limitations, individuals with TBI must be monitored, and their lifestyles must be adjusted to minimize PTBIF. Regarding physical activity interventions, Borgaro and colleagues [Borgaro et al. 2005] suggested that engaging patients in physical activity increased endurance, improved restful sleep, and may help reduce fatigue. Aerobic exercise and other forms of physical activity reduce fatigue levels in individuals with cancer, multiple sclerosis, and other conditions [Krupp et al. 2010; Mitchell, 2010], but whether or not aerobic exercise benefits individuals with PTBIF warrants further studies. Among all physical interventions, only aquatic physical activity was effective for PTBIF [Driver and Ede, 2009], while fitness-center-based exercise [Hassett et al. 2009], Tai Chi [Gemmell and Leathem, 2006] and aerobic training [Bateman et al. 2001] had no impact on PTBIF. However, the evidence is weak because of the small and underpowered sample sizes.

Two studies indicated that CBI might be effective in reducing PTBIF [Johansson et al. 2012a; Björkdahl et al. 2013]. However, another study by Hodgson and colleagues questioned these results [Hodgson et al. 2005], which were considered ‘effective’ by Cantor and colleagues [Cantor et al. 2014] in the systematic review. TBI-related cognitive impairment and behavioral deficiencies can lead to increased PTBIF, as patients may lack the capacity and ability to expend the effort necessary to perform previously manageable tasks (i.e. the coping hypothesis). Through adopting a collaborative team approach to address patient concerns, cognitive and behavioral skills are beneficial to individuals with PTBIF [Heimberg, 2002]. Since research in other patient populations (multiple sclerosis, cancer and chronic fatigue syndrome) also suggests that CBI is effective in the management and reduction of fatigue [Montgomery et al. 2009; Krupp et al. 2010; Wiborg et al. 2010], CBI approaches are worth further pursuing.

The effects of the two related electro–biofeedback therapies were questionable, as they had elevated risks of bias [Smith et al. 1994; Schoenberger et al. 2001]. One study on light therapy presented better results in managing PTBIF, but further study is required to confirm its efficacy [Sinclair et al. 2014].

From the three additional RCTs [Bateman et al. 2001; Johansson et al. 2012a; Björkdahl et al. 2013] not included in Cantor’s systematic review, MBSR [Johansson et al. 2012a] and computerized working-memory training [Björkdahl et al. 2013] interventions were effective, but aerobic training was ineffective [Bateman et al. 2001]. Although the numbers of subjects with TBI included in these studies were small, they should not be ignored because of their positive results concerning PTBIF. In addition, some other CAM interventions have been demonstrated to be effective for fatigue, such as massage, tuina, qigong for chronic fatigue syndrome [Alraek et al. 2011], as well as yoga and acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue [Finnegan-John et al. 2013], but these interventions have not been examined for PTBIF. Therefore, it is worth determining whether these interventions can reduce PTBIF, since PTBIF management remains unstandardized and unsatisfied.

There are some limitations to the present systematic review. First, study quality varied among the included studies. Second, heterogeneity may exist because of differences in intervention style, study parameters, and outcome measurements, which impede comparisons between studies. Discrepancies also exist in the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Third, though a systematic search of multiple databases was undertaken, some unpublished grey literature might have been missed. Thus, potential publication bias and selection bias could not be eliminated. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted cautiously.

In conclusion, among complementary and alternative interventions, physical activity, MBSR, computerized working-memory training, and blue-light therapy may be beneficial in PTBIF treatment. However, due to the limited number of RCTs for each intervention in addition to methodological problems and high risks of bias in the most included studies, the quality of evidence was judged to be low/very low using the GRADE system. Further RCTs with larger sample sizes and more scientific rigor in particular for all of these interventions are necessary to determine the efficacy of these treatments in PTBIF.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article: Shaanxi Province Natural Science Basic Research Foundation of China (2016JM3015) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81671097).

Conflict of interest statement: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Gang-Zhu Xu, Key Laboratory of Shaanxi Province for Craniofacial Precision Medicine Research, Stomatological Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University and First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Medical University, Xi’an, China.

Yan-Feng Li, First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Medical University, China.

Mao-De Wang, First Affiliated Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University, China.

Dong-Yuan Cao, Key Laboratory of Shaanxi Province for Craniofacial Precision Medicine Research, Stomatological Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University, 98 West 5th Road, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710004, China.

References

- Alraek T., Lee M., Choi T., Cao H., Liu J. (2011) Complementary and alternative medicine for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med 11: 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda J., Stern R., Somerville J. (1999) Measurement of mood states in stroke patients: validation of the visual analog mood scales. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 80: 676–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balshem H., Helfand M., Schünemann H., Oxman A., Kunz R., Brozek J., et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 64: 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Culpan F., Pickering A., Powell J., Scott O., Greenwood R. (2001) The effect of aerobic training on rehabilitation outcomes after recent severe brain injury: a randomized controlled evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 82: 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay E., De-Leon M. (2010) Chronic stress and fatigue-related quality of life after mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 26: 355–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkdahl A., Akerlund E., Svensson S., Esbjörnsson E. (2013) A randomized study of computerized working memory training and effects on functioning in everyday life for patients with brain injury. Brain Inj 27: 1658–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgaro S., Baker J., Wethe J., Prigatano G., Kwasnica C. (2005) Subjective reports of fatigue during early recovery from traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 20: 416–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnik T., Englander J., Katznelson L. (2007) Fatigue after TBI: association with neuroendocrine abnormalities. Brain Inj 21: 559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor J., Ashman T., Bushnik T., Cai X., Farrellcarnahan L., Gumber S., et al. (2014) Systematic review of interventions for fatigue after traumatic brain injury: a NIDRR traumatic brain injury model systems study. J Head Trauma Rehabil 29: 490–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor J., Ashman T., Gordon W., Ginsberg A., Engmann C., Egan M., et al. (2008) Fatigue after traumatic brain injury and its impact on participation and quality of life. J Head Trauma Rehabil 23: 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor J., Bushnik T., Cicerone K., Dijkers M., Gordon W., Hammond F., et al. (2012) Insomnia, fatigue, and sleepiness in the first 2 years after traumatic brain injury: an NIDRR TBI model system module study. J Head Trauma Rehabil 27: E1-E14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor J., Gordon W., Gumber S. (2013) What is post TBI fatigue? Neurorehabilitation 32: 875–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkers M., Bushnik T. (2008) Assessing fatigue after traumatic brain injury: an evaluation of the Barroso Fatigue Scale. J Head Trauma Rehabil 23: 3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver S., Ede A. (2009) Impact of physical activity on mood after TBI. Brain Inj 23: 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan-John J., Molassiotis A., Richardson A., Ream E. (2013) A systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine interventions for the management of cancer-related fatigue. Integr Cancer Ther 12: 276–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk J., Ritvo P., Ross L., Haase D., Marrie T., Schlech W. (1994) Measuring the functional impact of fatigue: initial validation of the fatigue impact scale. Clin Infect Dis 18: S79–S83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmell C., Leathem J. (2006) A study investigating the effects of Tai Chi Chuan: individuals with traumatic brain injury compared to controls. Brain Inj 20: 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkarainen H., Hakamies L. (1978) Piracetam in the treatment of post-concussional syndrome. A double-blind study. Eur Neurol 17: 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett L., Moseley A., Tate R., Harmer A., Fairbairn T., Leung J. (2009) Efficacy of a fitness centre-based exercise programme compared with a home-based exercise programme in traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med 41: 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg R. (2002) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder: current status and future directions. Biol Psychiatry 51: 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks E., Senior H., Purdy S., Barker-Collo S., Larkins B. (2007) Interventions for fatigue management after traumatic brain injury (protool). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007: CD006448. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson J., McDonald S., Tate R., Gertler P. (2005) A randomised controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioural therapy program for managing social anxiety after acquired brain injury. Brain Impair 6: 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Jadad A., Moore R., Carroll D., Jenkinson C., Reynolds D., Gavaghan D., et al. (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 17: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson B., Berglund P., Rönnbäck L. (2009) Mental fatigue and impaired information processing after mild and moderate traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 23: 1027–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson B., Bjuhr H., Rönnbäck L. (2012. a) Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) improves long-term mental fatigue after stroke or traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 26: 1621–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson B., Carlsson A., Carlsson M., Karlsson M., Nilsson M., Nordquist-Brandt E., et al. (2012. b) Placebo-controlled cross-over study of the monoaminergic stabiliser (−)-OSU6162 in mental fatigue following stroke or traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropsychiatr 24: 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson B., Wentzel A., Andréll P., Odenstedt J., Mannheimer C., Rönnbäck L. (2014) Evaluation of dosage, safety and effects of methylphenidate on post-traumatic brain injury symptoms with a focus on mental fatigue and pain. Brain Inj 28: 304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp L., Larocca N., Muirnash J., Steinberg A. (1989) The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol 46: 1121–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp L., Serafin D., Christodoulou C. (2010) Multiple sclerosis-associated fatigue. Expert Rev Neurother 10: 1437–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachapelle D., Finlayson M. (1998) An evaluation of subjective and objective measures of fatigue in patients with brain injury and healthy controls. Brain Inj 12: 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S. (2010) Cancer-related fatigue: state of the science. PM R 2: 364–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock V. (2001) Fatigue management: evidence and guidelines for practice. Cancer 92: 1699–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery G., Kangas M., David D., Hallquist M., Green S., Bovbjerg D., et al. (2009) Fatigue during breast cancer radiotherapy: an initial randomized study of cognitive-behavioral therapy plus hypnosis. Health Psychol 28: 317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olver J., Ponsford J., Curran C. (1996) Outcome following traumatic brain injury: a comparison between 2 and 5 years after injury. Brain Inj 10: 841–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet M., Morin C. (2006) Fatigue following traumatic brain injury: frequency, characteristics, and associated factors. Rehabil Psychol 51: 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ponsford J., Ziino C., Parcell D., Shekleton J., Roper M., Redman J., et al. (2012) Fatigue and sleep disturbance following traumatic brain injury—their nature, causes, and potential treatments. J Head Trauma Rehabil 27: 224–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakellaris G., Nasis G., Kotsiou M., Tamiolaki M., Charissis G., Evangeliou A. (2008) Prevention of traumatic headache, dizziness and fatigue with creatine administration. A pilot study. Acta Paediatr 97: 31–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberger N., Shif S., Esty M., Ochs L., Matheis R. (2001) Flexyx neurotherapy system in the treatment of traumatic brain injury: an initial evaluation. J Head Trauma Rehabil 16: 260–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid A., Wilkinson K., Marcu S., Shapiro C. (2012) Profile of Mood States (POMS).In: Shahid A., Wilkinson K., Marcu S., Shapiro C. (eds) STOP, THAT and One Hundred Other Sleep Scales. New York, NY: Springer, pp; 285–286. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair K., Ponsford J., Taffe J., Lockley S., Rajaratnam S. (2014) Randomized controlled trial of light therapy for fatigue following traumatic brain injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 28: 303–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R., Tiberi A., Marshall J. (1994) The use of cranial electrotherapy stimulation in the treatment of closed-head-injured patients. Brain Inj 8: 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiborg J., Knoop H., Stulemeijer M., Prins J., Bleijenberg G. (2010) How does cognitive behaviour therapy reduce fatigue in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome? the role of physical activity. Psychol Med 40: 1281–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wischenka D., Marquez C., Felsted K. (2016) Benefits of physical activity on cognitive functioning in older adults. Ann Rev Gerontol Geriatr 36: 103–122. [Google Scholar]