Abstract

Background

Nausea and occasional vomiting in early pregnancy is common. Why some women experience severe nausea and occasional vomiting in early pregnancy is unknown. Causes are multifactorial and only symptomatic treatment options are available, although adverse birth outcomes have been described. Helicobacter pylori infection has been implicated in the cause of nausea and occasional vomiting in early pregnancy.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to investigate the association of H pylori with vomiting severity in pregnancy and its effect on birth outcome.

Study Design

We assembled a population-based prospective cohort of pregnant women in The Netherlands. Enrolment took place between 2002 and 2006. H pylori serology was determined in mid gestation. Women reported whether they experienced vomiting in early, mid, and late gestation. Maternal weight was measured in the same time periods. Birth outcomes were obtained from medical records. Main outcome measures were vomiting frequency (no, occasional, daily) and duration (early, mid, late gestation), maternal weight gain, birthweight, small for gestational age, and prematurity. Data were analyzed with the use of multivariate regression.

Results

We included 5549 Women, of whom 1932 (34.8%) reported occasional vomiting and 601 (10.8%) reported daily vomiting. Women who were H pylori-positive (n=2363) were more likely to report daily vomiting (adjusted odds ratio, 1.44; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.78). H pylori positivity was associated with a reduction of total weight gain in women with daily vomiting (adjusted difference, -2.1 kg; 95% confidence interval, -2.7 to -1.5); infants born to women with H pylori and daily vomiting had slightly reduced birthweight (adjusted difference -60g; 95% confidence interval, -109 - -12) and an increased risk of being small for gestational age (adjusted odds ratio, 1.49; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-2.14). H pylori and daily vomiting did not significantly affect prematurity rate.

Conclusion

This study suggests that H pylori is an independent risk factor for vomiting in pregnancy. In women with daily vomiting, H pylori is also associated with low maternal weight gain, reduced birth weight, and small for gestational age. Because effective treatments for severe nausea and occasional vomiting in early pregnancy are currently lacking, the effect of H pylori eradication therapy on nausea and occasional vomiting in early pregnancy symptom severity should be the target of future studies.

Introduction

Nausea and occasional vomiting in early pregnancy (NVP) affects 50-90% of pregnant women in the first half of gestation,1 and can impact greatly maternal wellbeing and quality of life.2 When vomiting is severe or protracted or is accompanied by weight loss, dehydration, electrolyte disturbances, or hospitalization, it is referred to as hyperemesis gravidarum (HG).3 In the absence of an internationally recognized definition, HG and severe NVP are likely to overlap in studies.4

In the Western world, severe NVP more often affects socially disadvantaged women and those of non-Western ethnicity.5 To date, there is no clear explanation for the risk differences between Western and non-Western ethnic groups. In a recent metaanalysis, colonization with the gastric bacterium Helicobacter pylori was positively associated with severe NVP (odds ratio (OR) 3.34, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.92–4.81).6 Interestingly, the H pylori prevalence in pregnant women of Western ethnicity is much lower than in women of non-Western ethnicity.7 The association between H pylori and severe NVP has been replicated in several studies, but mainly in non-Western populations in which the prevalence of H pylori is high.8–10 Three small studies on this topic have been conducted in a Western setting but reported conflicting findings.11–13 Furthermore, some have suggested that more pathogenic variants of H pylori, such as cytotoxin associated gene A (CagA)-positive strains are more often found among women with severe NVP.14 Several small studies have suggested that H pylori infection is not only associated with the presence of severe NVP, but also associated positively with symptom severity8 and persistence.10

Severe NVP has been associated repeatedly with adverse birth outcome, which includes low birthweight, small for gestational age (SGA), and prematurity;15 however, the mechanism by which severe NVP may lead to adverse birth outcomes is not well understood. Weight loss or insufficient weight gain during pregnancy has been suggested to play a role,16, 17 although other factors such as the presence of H pylori on birth outcome has not been investigated.

In the present study, we investigated the hypothesis that H pylori is associated with vomiting severity in pregnancy and contributes to adverse birth outcomes in women with severe NVP. Furthermore, we investigated whether H pylori explains the marked ethnic differences in maternal daily vomiting incidence. The study was performed in a large prospective multiethnic cohort study in the Netherlands, the Generation R study.

Methods

Study population

This study was embedded in the Generation R study, which is a population-based, prospective cohort study from early pregnancy until young adulthood. Approval of the Generation R Study was obtained from the Central Committee on Research that involves Human Subjects in the Netherlands via the Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam. All participants provided written informed consent. The study is still ongoing and conducted in Rotterdam, which is the second largest city of the Netherlands with a multiethnic community. Study design and aims have been described in detail elsewhere. 18 In brief, 8879 pregnant women were enrolled from 2002-2006. Women underwent physical examinations (measurement of height and weight) and filled out questionnaires in early, mid, and late gestation. These questionnaires contained information on medical history, socioeconomic background, lifestyle, and current pregnancy. The number of physical examinations and questionnaires received was dependent on the gestational age at enrolment. Serum samples were obtained during mid gestation. 19

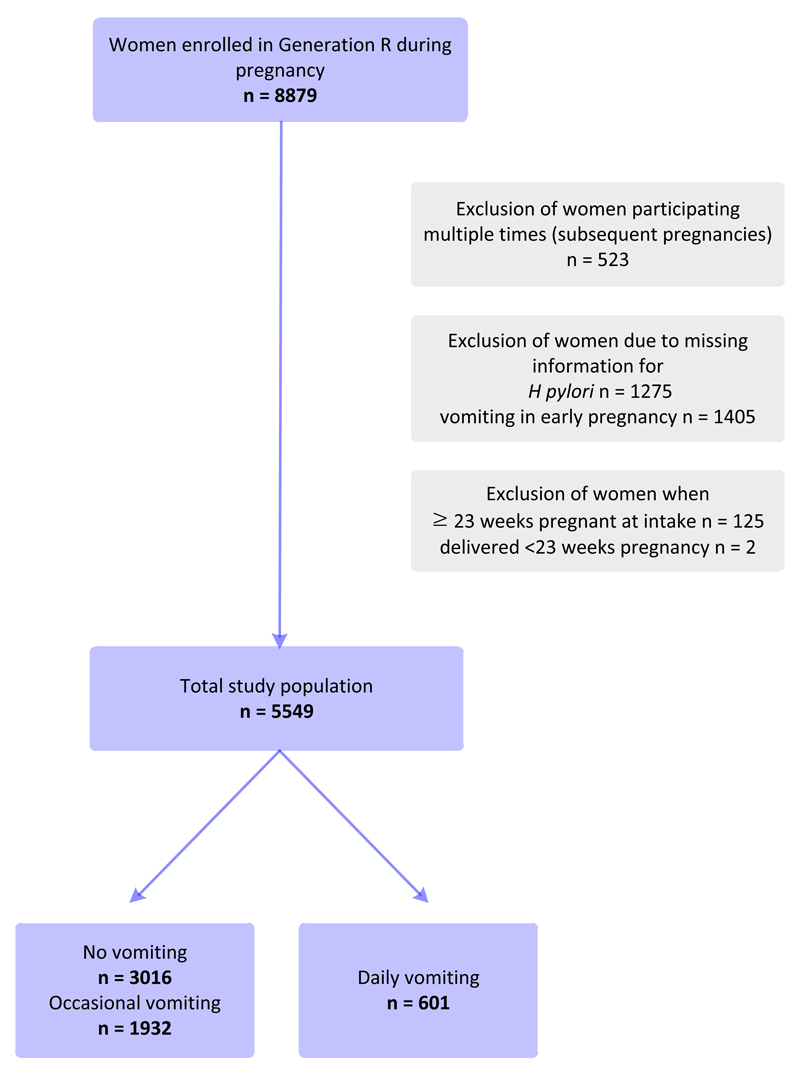

In this study, 5549 women with complete data on vomiting status in early gestation and H pylori serology in mid gestation were included. Women enrolled after 22 weeks gestation with no information on previous vomiting status were excluded, because vomiting that starts after this gestational age is likely to have other underlying causes. Women were also excluded if they participated multiple times in subsequent pregnancies or delivered at <23 weeks gestation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of participant selection.

Definition of daily vomiting

There is no internationally recognized definition for severe NVP or HG. In this study, women were asked in every questionnaire whether they experienced vomiting for the past 3 months. Answers ranged from “never” to “daily” on a 1-5 scale (never, less than once a week, once a week, few times a week, daily). If daily vomiting has been present for 3 months at study enrollment, women were considered to have severe NVP. When vomiting occurred <1 time each week, once a week, or few times a week, women were considered to have occasional vomiting. Because occasional vomiting in pregnancy is considered physiological, women with no vomiting and occasional vomiting were considered the reference group, despite the fact there were some statistical differences in baseline characteristics between women with no vomiting and occasional vomiting (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristics of women and neonates according to daily vomiting.

| Characteristics n= |

Total population 5549 |

No vomiting 3016 |

Occasional vomiting 1932 |

Daily vomiting 601 |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (y) | 29.7±5.2 | 30.6±5.0 | 28.9±5.1 | 27.6±5.0 | <0.001 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 22.6 (20.8-25.5) | 22.4 (20.7-25.1) | 22.7 (20.7-25.5) | 23.7 (21.1-27.6) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||

| Western | 62.7 | 71.6 | 58.5 | 31.8 | |

| Non-Western | 37.3 | 28.4 | 41.5 | 68.2 | |

| Ethnic groups | <0.001 | ||||

| Dutch | 50.8 | 58.9 | 46.7 | 23.5 | |

| Other Western | 11.9 | 12.8 | 11.7 | 8.3 | |

| Moroccan | 6.0 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 13.7 | |

| Turkish | 8.6 | 6.5 | 9.0 | 18.1 | |

| Surinamese | 9.2 | 7.4 | 10.5 | 14.6 | |

| Cape Verdean/Dutch Antilles | 7.6 | 5.7 | 9.0 | 12.4 | |

| Other non-Western | 5.9 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 9.5 | |

| Education level | <0.001 | ||||

| Primary | 10.6 | 8.2 | 11.2 | 20.0 | |

| Secondary | 47.3 | 42.5 | 50.7 | 59.9 | |

| Higher | 42.1 | 49.2 | 38.1 | 20.1 | |

| Smoking | 18.1 | 17.7 | 18.3 | 19.3 | 0.62 |

| IgG anti-H. pylori positive* | 42.6 | 36.5 | 45.2 | 64.4 | <0.001 |

| CagA + | 14.6 | 11.9 | 15.4 | 41.1 | <0.001 |

| Pregnancy characteristics | |||||

| Nulliparous | 61.8 | 63.1 | 62.0 | 54.9 | <0.05 |

| Twin pregnancy | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.23 |

| Gestational age at enrollment (wk) | 13.8 (12.4-16.2) | 13.6 (12.2-16.1) | 13.8 (12.5-16.4) | 14.2 (12.5-16.6) | <0.05 |

| Duration of daily vomiting | |||||

| Early gestation | 7.2 | - | - | 66.6 | |

| Mid gestation | 2.4 | - | - | 22.1 | |

| Late gestation | 1.2 | - | - | 11.3 | |

| Total weight gain (kg)** | 10.5±5.1 | 10.9±4.9 | 10.6±5.2 | 8.5±5.9 | <0.001 |

| PE or HELLP-syndrome | 2.7 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 0.31 |

| Neonatal characteristics | |||||

| Gestational age at birth (d) | 281 (273-287) | 281 (274-287) | 281 (274-287) | 280 (273-286) | 0.18 |

| Prematurity (<37 wk) | 5.6 | 5.3 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 0.51 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3402±569 | 3422±563 | 3387±572 | 3360±577 | <0.05 |

| SGA (<p10) | 10.1 | 9.5 | 10.2 | 11.9 | 0.19 |

Data represent mean±SD, median (IQR) or %. Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index; IgG: immune globuline G; CagA: Cytotoxin-associated gene A protein; PE: preeclampsia; HELLP-syndrome: hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets; SGA: small for gestational age.

CagA-negative or positive

Total weight gain based on pre-pregnancy weight and measured weight in late gestation

Symptom severity

Symptom severity was explored according to vomiting frequency (no, occasional, daily vomiting) and vomiting duration. When daily vomiting for the past 3 months was reported in both the first and second questionnaire, women were considered to have daily vomiting that persisted into mid gestation. Similarly, when daily vomiting was reported in all 3 questionnaires, women were considered to have daily vomiting that persisted into late gestation. Because inadequate weight gain is often part of severe NVP, the association of H pylori and daily vomiting with total maternal weight gain (kilograms) was also investigated. Weight gain was based on self-reported prepregnancy weight and measured weight in late gestation.

H pylori serology

Mid pregnancy (18-25 weeks) serum samples were used to determine H pylori serology. H pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody levels were examined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), with the use of whole cell antigens.20 A separate ELISA was performed to determine serum IgG antibodies against CagA protein.21 Both ELISAs were validated locally, by adaption of the ELISA properties based on positive and negative controls.

Pregnancy outcomes

Gestational age at birth, birthweight, and neonatal sex were obtained from medical records.18 Prematurity was defined as birth at <37 weeks gestation; SGA was defined as gestational age-adjusted birthweight at <10th percentile in this study’s population, based on the reference standard by Niklasson et al.22

Covariates

General characteristics

Maternal age was assessed at enrolment. Prepregnancy body mass index (kilograms per square meter) was calculated with the use of self-reported prepregnancy weight and height measured at enrolment. All sociodemographic characteristics were self-reported. Ethnicity was determined according to the definition of Statistics Netherlands23 by country of birth of the pregnant woman and her parents. Based on the urban population of Rotterdam, the following ethnic groups were identified: Dutch, “other Western” (women who originated from Europe, North America, Oceania, Japan, or Indonesia), Surinamese, Turkish, Cape Verdean/Dutch Antilles, Moroccan and “other non-Western” (women who originated from Africa, Asia, or South or Central America). Dutch and “other Western” ethnic groups were classified as Western, all other ethnic groups that were described were classified as non-Western. Educational level served as a proxy for socioeconomic status and was based on the highest completed education (none or primary school, secondary school, higher education). Smoking during pregnancy was also self-reported.

Pregnancy characteristics

All major pregnancy characteristics and outcomes were obtained from medical records18 that included parity, twin pregnancy, diabetes mellitus gravidarum, and information on hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclampsia, and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets (HELLP) syndrome).

Data analysis

Differences in subject characteristics between groups were evaluated with the use of chi-square tests for proportions and 1-way analysis of variance or Kruskal Wallis for continuous variables. Logistic regression analysis was performed to study associations between H pylori seropositivity and vomiting frequency and persistence. We adjusted for maternal age, parity, ethnicity (ethnic groups), education level, and smoking (model 2). Effects of H pylori and daily vomiting on maternal weight gain and birth outcomes were explored with linear regression analysis. These analyses were adjusted for neonatal sex, gestational age at birth, twin pregnancy, maternal age, parity, diabetes mellitus gravidarum, hypertensive disorders, ethnicity, education level, prepregnancy body mass index, and smoking. Sensitivity analyses were performed by including maternal weight gain based on measured weight in early and late gestation, additional adjustment for gestational age at time of measured weight in late gestation, and the exclusion of twin pregnancies. We also investigated whether H pylori explained ethnic differences in daily vomiting. Using logistic regression analysis, we first explored the association of ethnicity and daily vomiting, followed by adjustment for H pylori (model 2). We then further adjusted for maternal age, parity, education level, and smoking (model 3). Possible strain-specific effects on vomiting frequency were assessed among women who were H pylori-positive (CagA-positive and -negative). Because of small numbers, analyses on birth outcomes were not repeated in this subgroup. Last, sensitivity analyses were performed to examine whether the associations between H pylori, vomiting severity, and birth outcomes were similar for Dutch women only (largest ethnic group). Possible confounders were identified with directed acyclic graphs, 24 based on known risk factors for HG. Missing data of covariates were input with the use of multiple imputations (5 datasets). The percentages of missing values within the population for analysis were <2%, except for prepregnancy weight (10.8%) and total weight gain (14.1%). All analyses were performed with the use of IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 21.0; SPSS, IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Baseline characteristics of women with and without daily vomiting

The study population consisted of 5549 pregnant women, of which 601 women experienced daily vomiting in early gestation (10.8%). Compared with women excluded from the analysis (n=3330; Figure 1), women who were included were slightly more often nulliparous, of Western ethnicity, and more highly educated (data not shown). Table 1 describes sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of women who were included and infants according to vomiting frequency. Women with daily vomiting were younger, more often of non-Western ethnicity, less highly educated, and with a higher body mass index than women with no or occasional vomiting. Women with daily vomiting were more often H pylori positive (64.4%), compared with women with no vomiting (36.5%) and occasional vomiting (45.2%; P<.001), and more often infected by CagA-positive strains.

Does H pylori underlie symptom severity?

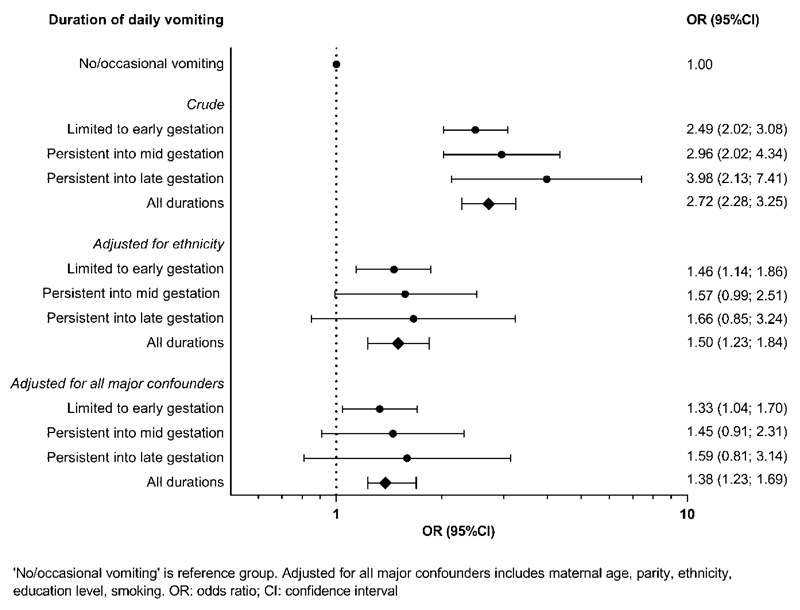

After adjustment for confounders, the association between H pylori and daily vomiting was still present (Table 2). H pylori was also associated positively with symptom duration: 39.9% of women with no or occasional vomiting were H pylori positive, compared with 62.4% of women with daily vomiting in early pregnancy, 66.4% of women with daily vomiting persistent into mid pregnancy, and 72.1% of women with daily vomiting persistent into late pregnancy (P<.001). Logistic regression for the association of H pylori and daily vomiting duration is shown in Figure 2. After adjustment for confounders, the association was reduced, but a similar trend was seen. Furthermore, women with daily vomiting had reduced weight gain in pregnancy (Table 3). The presence of H pylori further reduced weight gain in these women.

Table 2. Logistic regression for vomiting frequency and H pylori.

| No vomiting | Occasional vomiting | Daily vomiting | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Crude | |||||

| H pylori | 1.0 | 1.44** | 1.28; 1.61 | 3.14** | 2.62; 3.77 |

| Adjusted | |||||

| H pylori | 1.0 | 1.10 | 0.96; 1.26 | 1.44* | 1.16; 1.78 |

‘No vomiting’ is reference group. Adjusted for maternal age, parity, ethnicity, education level, smoking. OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

p<0.05

p<0.001

Figure 2. Logistic regression for H pylori and daily vomiting according to symptom duration.

Table 3. Linear and logistic regression for H pylori and/or daily vomiting, maternal and neonatal outcome.

| H.pylori | Daily vomiting | H. pylori + daily vomiting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β/OR | 95% CI | β/OR | 95% CI | β/OR | 95% CI | |

| Maternal outcome | ||||||

| Total weight gain (kg) | -0.1 | -0.4; 0.2 | -1.2* | -1.9; -0.4 | -2.1** | -2.7;-1.5 |

| Neonatal outcome | ||||||

| Birthweight (g) | -31* | -58; -4 | 31 | -30; 92 | -60* | -109; -12 |

| SGA (<p10) | 1.08 | 0.87; 1.34 | 0.77 | 0.45; 1.30 | 1.49* | 1.04; 2.14 |

| Prematurity (<37 wk) | 1.13 | 0.85; 1.49 | 1.21 | 0.67; 2.18 | 1.35 | 0.83; 2.21 |

‘No/occasional vomiting and no H. pylori’ is reference group. Adjusted for neonatal sex, gestational age at birth, twin pregnancy, maternal age, parity, diabetes gravidarum, hypertensive disorders, ethnicity, education level, pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking. β: difference; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; SGA: small for gestational age.

p<0.05

p<0.001

Does H pylori underlie the association between daily vomiting and poor pregnancy outcome?

We also examined the effects of H pylori and daily vomiting on pregnancy outcome (Table 3). After adjustment for confounders, there was no significant association between H pylori or daily vomiting and SGA or prematurity. However, in infants born to women with H pylori, birthweight was slightly reduced. In infants born to women with both H pylori and daily vomiting, birthweight was further reduced, and the risk for SGA was increased. Maternal weight gain was associated significantly with birthweight (for every kilogram of maternal weight gain adjusted birthweight difference was 18g (95% CI, 15-21; P<.001).

Does H pylori underlie ethnic differences in daily vomiting?

Daily vomiting occurred more often in women of non-Western ethnicity (crude OR, 4.25; 95%CI, 3.55-5.10). After adjustment for H pylori, the OR diminished only slightly (model 2; adjusted OR, 3.47; 95% CI, 2.84-4.24). Across all ethnicities, the OR for daily vomiting according to the presence of H pylori was similar. After further adjustment for major confounders, non-Western ethnicity remained significantly associated with daily vomiting (model 3; adjusted OR, 2.49; 95% CI, 1.99-3.10). In fact, this was true for all non-Dutch ethnicities (Supplementary Table 1).

Are there H pylori strain specific effects?

Subanalysis among women who were H pylori-positive (n=2363) showed that women who were CagA-positive were more likely to experience daily vomiting compared with women who were H pylori-positive but CagA-negative (crude OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.09-1.70). After adjustment for ethnicity, this difference was rendered nonsignificant (adjusted OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.93-1.48).

Comment

This study confirms the association between H pylori and daily vomiting and adds to the existing evidence that the presence of H pylori is associated with a reduction of total maternal weight gain. More importantly, we found evidence that H pylori contributes to reduced birth weight and SGA, which makes H pylori eradication in pregnancy in women with severe NVP an attractive target for future intervention studies.

Previous studies have established that H pylori infection is associated with severe NVP, although the strength and size of these associations varied between different populations and countries. 6, 25 Our findings confirm this association. Similarly, the prevalence of H pylori infection among Dutch (24%) and non-Dutch women (64%) in this cohort7 is in line with the existing literature. We found that H pylori remained a risk factor for daily vomiting after adjustment for ethnicity and socioeconomic status, which lends further support to the hypothesis that H pylori is implicated causally in the pathophysiologic condition of severe NVP.

Several studies that have evaluated birth outcome in pregnancies that are complicated by severe NVP have demonstrated modest negative effects on birthweight, SGA, and prematurity rates. 15 Both H pylori and severe NVP have been implicated in placental dysfunction disorders. 26, 27 Interestingly, we observed an increased risk for SGA only in women who were H pylori-positive with daily vomiting, which might explain why not all studies found adverse birth outcomes after pregnancies that were complicated by severe NVP. SGA may be a result of poor placentation, including failed remodeling of the spiral arteries. 25 Causes of impaired remodelling might include an excessive or atypical maternal immune response to trophoblasts. 26 Franceschi et al27 have shown that anti-CagA antibodies in vitro were able to recognize b-actin on the surface of trophoblast cells in a dose-dependent binding activity. This binding resulted in impaired cytotrophoblast invasiveness, which is crucial for the development of the placental syndrome. This study may provide a biologic explanation for the epidemiologic association between H pylori and the placental syndrome. Taken together, it is possible that H pylori has a local gastrointestinal effect that leads to NVP symptoms and a systemic placental effect that results in an increased risk for SGA. A similar pathway might underlie the relationship between severe NVP and preeclampsia; however, this needs further study. Additionally, an interaction of H pylori and NVP might result in reduced maternal weight gain, which in turn negatively affects birth outcome.

Most likely H pylori is acquired at a young age and leads to lifelong colonization, unless specifically treated.28 More pathogenic variants of H pylori, in particular CagA-positive strains, are associated with increased gastric inflammation.21 Like Xia et al,14 we found that women who were CagA positive were more likely to experience daily vomiting compared with women who were H pylori-positive but CagA negative, which might be partly explained by differences in geographic distribution of CagA-strains.

This study was embedded in a large prospective cohort study; data collection was performed by trained research assistants. Questionnaires that inquired about the presence of vomiting were collected prospectively, which made the risk of recall bias low. If misclassification of vomiting frequency had occurred, the presented effects could be underestimated. Furthermore, we were unable to confirm HG diagnosis based on hospital admission or other more commonly used criteria,29 and numbers for persistent vomiting in late pregnancy were small. Because of the observational design, residual confounding might still be an issue. Based on the nature of the study, we did not adjust for multiple testing. Despite these limitations, characteristics of women who experienced daily vomiting largely resembled previous reported data on patient with severe NVP.30 Additionally, we were informed about maternal weight gain and symptom persistence and were able to adjust for all previously described major confounders known to be associated with H pylori and severe NVP12 with detailed information on ethnic background. Sensitivity analyses on the studied associations that included only Dutch women resulted in similar findings (data not shown). We were underpowered to show that the presence of H pylori was associated with daily vomiting persistence or prematurity or to study potential effects of H pylori strains on vomiting severity and pregnancy outcome.

There is debate on the accuracy of various diagnostic strategies to establish H pylori infection. Many studies,6 including this study, have investigated the presence of H pylori IgG antibodies in serum using ELISA. Other tests with greater accuracy have replaced serology in clinical practice; however, because of low costs, acceptability to patients, and practicability, serology is still indicated for epidemiologic studies.31 The declining H pylori prevalence in The Netherlands might affect the positive predictive value of serology,32 but it is unlikely that this has influenced our findings. Unlike most infectious diseases, H pylori infection does not result in acquired immunity. Therefore, IgG anti-H pylori and anti-CagA antibodies are indicative of active disease, unless eradication therapy has been prescribed in the previous months.33 This would have been rare among pregnant women.

To date, no effective treatment options are available for severe NVP, nor do we know how to identify patients at risk for persistent symptoms during the course of pregnancy. Several case studies have reported that H pylori eradication effectively relieved symptoms in women with persistent vomiting that was unresponsive to conventional treatment.34–36 H pylori eradication therapy in The Netherlands normally consists of triple therapy, including a proton pump inhibitor, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin or metronidazole.32 A metaanalysis performed by Gill et al37 showed no teratogenic effects of proton pump inhibitor use in early pregnancy. No teratogenic effects were described for amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole.38–40 Clarithromycin, but not amoxicillin and proton pump inhibitor, was associated with miscarriage when administered in the first trimester.40 These studies indicate that triple therapy that consisted of proton pump inhibitor, amoxicillin, and metronidazole might be used safely in pregnancy. If remaining circulating anti-H pylori and CagA antibodies have the ability to affect placental function, H pylori eradication before pregnancy in women with a history of severe NVP should be considered. Further evidence to confirm the effectiveness of H pylori eradication on NVP symptom reduction and adverse birth outcome is needed from randomized controlled trials.

In conclusion, our study suggests that H pylori is an independent risk factor for vomiting in pregnancy, which leads to low maternal weight gain, reduced birthweight and increased risk of SGA. Because treatment options for severe NVP currently are lacking, the effect of H pylori eradication therapy on NVP severity and birth outcome should be target of future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Generation R Study is being conducted by the Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University Rotterdam in close collaboration with the Municipal Health Service Rotterdam area, Rotterdam and the Stichting Trombosedienst and Artsenlaboratorium Rijnmond, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of children and their parents, general practitioners, hospitals, midwives, and pharmacies in Rotterdam.

The general design of the Generation R Study is made possible by financial support from the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport and Ministry of Youth and Families; V.W.J. received grants from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (VIDI 016.136.361) and European Research Council (ERC-2014-CoG-648916). These funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jarvis S, Nelson-Piercy C. Management of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. BMJ. 2011;342:d3606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lacasse A, Rey E, Ferreira E, Morin C, Bérard A. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: what about quality of life? BJOG. 2008;115(12):1484–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niebyl JR. Clinical practice. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(16):1544–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1003896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Practice Bulletin No. 153. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e12–24. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vikanes A, Grjibovski AM, Vangen S, Magnus P. Variations in prevalence of hyperemesis gravidarum by country of birth: a study of 900,074 pregnancies in Norway, 1967-2005. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36(2):135–42. doi: 10.1177/1403494807085189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L, Li L, Zhou X, Xiao S, Gu H, Zhang G. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with an increased risk of hyperemesis gravidarum: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:278905. doi: 10.1155/2015/278905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.den Hollander WJ, Holster IL, den Hoed CM, van Deurzen F, van Vuuren AJ, Jaddoe VW, et al. Ethnicity is a strong predictor for Helicobacter pylori infection in young women in a multi-ethnic European city. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(11):1705–11. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Güngören A, Bayramoğlu N, Duran N, Kurul M. Association of Helicobacter pylori positivity with the symptoms in patients with hyperemesis gravidarum. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;288(6):1279–83. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-2869-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaban MM, Kandil HO, Elshafei AH. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in patients with hyperemesis gravidarum. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2014;347(2):101–5. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31827bef91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poveda GF, Carrillo KS, Monje ME, Cruz CA, Cancino AG. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastrointestinal symptoms on Chilean pregnant women. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2014;60(4):306–10. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.60.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frigo P, Lang C, Reisenberger K, Kolbl H, Hirschl AM. Hyperemesis gravidarum associated with Helicobacter pylori seropositivity. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(4):615–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandven I, Abdelnoor M, Wethe M, Nesheim B-I, Vikanes Å, Gjønnes H, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and hyperemesis gravidarum. An institution-based case–control study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23(7):491–8. doi: 10.1007/s10654-008-9261-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vikanes AV, Støer NC, Gunnes N, Grjibovski AM, Samuelsen SO, Magnus P, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and severe hyperemesis gravidarum among immigrant women in Norway: a case-control study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;167(1):41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia LB, Yang J, Li AB, Tang SH, Xie QZ, Cheng D. Relationship between hyperemesis gravidarum and Helicobacter pylori seropositivity. Chin Med J (Engl) 2004;117(2):301–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veenendaal MVE, van Abeelen AFM, Painter RC, van der Post JAM, Roseboom TJ. Consequences of hyperemesis gravidarum for offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2011;118(11):1302–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodds L, Fell DB, Joseph KS, Allen VM, Butler B. Outcomes of pregnancies complicated by hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(2 Pt 1):285–92. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000195060.22832.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grooten IJ, Painter RC, Pontesilli M, van der Post JAM, Mol BW, van Eijsden M, et al. Weight loss in pregnancy and cardiometabolic profile in childhood: findings from a longitudinal birth cohort. BJOG. 2015;122(12):1664–73. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaddoe VWV, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, van der Heijden AJ, van Iizendoorn MH, de Jongste JC, et al. The Generation R Study: design and cohort update 2012. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27(9):739–56. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9735-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaddoe VWV, Bakker R, van Duijn CM, van der Heijden AJ, Lindemans J, Mackenbach JP, et al. The Generation R Study Biobank: a resource for epidemiological studies in children and their parents. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22(12):917–23. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9209-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez-Perez GI, Dworkin BM, Chodos JE, Blaser MJ. Campylobacter pylori Antibodies in Humans. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109(1):11–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuipers EJ, Perez-Perez GI, Meuwissen SGM, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and atrophic gastritis: importance of the cagA status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(23):1777–80. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niklasson A, Ericson A, Fryer JG, Karlberg J, Lawrence C, Karlberg P. An update of the Swedish reference standards for weight, length and head circumference at birth for given gestational age (1977-1981) Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80:756–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1991.tb11945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alders M, editor. Classification of the population with a foreign background in the Netherlands. Paper presented to the conference 'The Measure and Mismeasure of Populations The statistical use of ethnic and racial categories in multicultural societies'; 17-18 December 2001; Paris: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shrier I, Platt RW. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Romero R. The "Great Obstetrical Syndromes" are associated with disorders of deep placentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jauniaux E, Poston L, Burton GJ. Placental-related diseases of pregnancy: involvement of oxidative stress and implications in human evolution. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(6):747–55. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franceschi F, Di Simone N, D'Ippolito S, Castellani R, Di Nicuolo F, Gasbarrini G, et al. Antibodies anti-CagA cross-react with trophoblast cells: a risk factor for pre-eclampsia? Helicobacter. 2012;17(6):426–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kusters JG, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(3):449–90. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00054-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fairweather DV. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1968;102(1):135–75. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(68)90445-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roseboom TJ, Ravelli ACJ, van der Post JA, Painter RC. Maternal characteristics largely explain poor pregnancy outcome after hyperemesis gravidarum. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;156(1):56–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaira D, Vakil N. Blood, urine, stool, breath, money, and Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 2001;48(3):287–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Numans ME, De Wit NJ, Dirven JAM, Heemstra-Borst CG, Hurenkamp GJB, Scheele ME, et al. NHG-Standaard Maagklachten (Derde herziening) Huisarts Wet. 2013;(56):26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61(5):646–64. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mansour G, Nashaat E. Role of Helicobacter pylori in the pathogenesis of hyperemesis gravidarum. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284(4):843–7. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1759-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacoby EB, Porter KB. Helicobacter pylori infection and persistent hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Perinatol. 1999;16(2):85–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strachan BK, Jokhi RP, Filshie GM. Persistent hyperemesis gravidarum and Helicobacter pylori. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;20(4):427. doi: 10.1080/01443610050112147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gill SK, O'Brien L, Einarson TR, Koren G. The safety of proton pump Iinhibitors (PPIs) in Ppregnancy: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(6):1541–5. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheehy O, Santos F, Ferreira E, Berard A. The use of metronidazole during pregnancy: a review of evidence. Current drug safety. 2015;10(2):170–9. doi: 10.2174/157488631002150515124548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Jonge L, Bos HJ, van Langen IM, de Jong-van den Berg LT, Bakker MK. Antibiotics prescribed before, during and after pregnancy in the Netherlands: a drug utilization study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(1):60–8. doi: 10.1002/pds.3492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andersen JT, Petersen M, Jimenez-Solem E, Broedbaek K, Andersen NL, Torp-Pedersen C, et al. Clarithromycin in early pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage and malformation: a register based nationwide cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.