Abstract

The lipid mediator platelet-activating factor (PAF) and oxidized glycerophosphocholine PAF agonists produced by ultraviolet B (UVB) have been demonstrated to play a pivotal role in UVB-mediated processes, from acute inflammation to delayed systemic immunosuppression. Recent studies have provided evidence that microvesicle particles (MVPs) are released from cells in response to various signals including stressors. Importantly, these small membrane fragments can interact with various cell types by delivering bioactive molecules. The present studies were designed to test if UVB radiation can generate MVP release from epithelial cells, and the potential role of PAF receptor (PAF-R) signaling in this process. We demonstrate that UVB irradiation of the human keratinocyte-derived cell line HaCaT resulted in the release of MVPs. Similarly, treatment of HaCaT cells with the PAF-R agonist carbamoyl PAF also generated equivalent amounts of MVP release. Of note, pretreatment of HaCaT cells with antioxidants blocked MVP release from UVB but not PAF-R agonist N-methyl carbamyl PAF (CPAF). Importantly, UVB irradiation of the PAF-R-negative human epithelial cell line KB and KB transduced with functional PAF-Rs resulted in MVP release only in PAF-R-positive cells. These studies demonstrate that UVB can generate MVPs in vitro and that PAF-R signaling appears important in this process.

INTRODUCTION

Ultraviolet B (290-320 nm; UVB) exposure found in sunlight mediates biological processes ranging from vitamin D metabolism to the generation of inflammatory responses and skin cancer in humans (1,2). UVB damages DNA and has toxic effects upon cell types including keratinocytes. Through its ability to act as a pro-oxidative stressor, UVB can also generate the lipid mediator platelet-activating factor (1-alkyl-2-acetyl glycerophosphocholine; PAF) (3-5). PAF exerts its effects via a single G-protein coupled transmembrane receptor (PAF-R) which is widely expressed on many cell types including keratinocytes (6,7). Activation of the epidermal PAF-R results in similar signaling pathways as UVB itself, suggesting that many of UVB-mediated effects are either mediated via the PAF-R, or can be modulated by concomitant PAF-R activation (8,9).

Microvesicle particles (MVP) are small membrane-bound vesicles released by numerous cell types and can be found in the circulation (10,11). MVPs can contain both nuclear and cytoplasmic components and are thought to provide a mechanism by which cells transmit signals systemically (12-15). Microvesicle particles are 200-1000 nm in diameter and differ from smaller (40-200 nm) exosomes. A previous study showed that exosomes secreted by keratinocytes enhance melanin synthesis by increasing both the expression and activity of melanosomal proteins. It has been shown that the function of keratinocyte-derived exosomes is phototype-dependent and is modulated by UVB (16). However, it is unclear whether UVB induces MVP release from keratinocytes and if the PAF-R is involved in this process.

In the current studies, we used a keratinocyte-derived cell line and epithelial carcinoma cell line to demonstrate that both UVB and PAF-R activation generate MVPs, and that UVB-mediated MVP formation involves the PAF-R. These studies provide a potential mechanism by which UVB can transmit systemic signals.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Reagents and UVB irradiation source

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless indicated otherwise. As previously reported, our UV source was a Philips F20T12/UVB lamp (9). The intensity of the UVB source was measured before each experiment using an IL1700 radiometer and a SED240 UVB detector (International Light) at a distance of 8 cm from the UVB source to the cells.

Cells and cell culture

The keratinocyte-derived cell line HaCaT and the human epithelial cell line KB were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Hyclone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT) as previously described (9,17,18). KB cells are a human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line that we have previously demonstrated are PAF-R-negative. PAF-R-negative KB cells were rendered PAF-R-positive (KBP) by transducing the MSCV2.1 retrovirus encoding the human leukocyte PAF-R as described previously (9,19) and compared with KB cells transduced with the vector alone (KBM).

Cell treatments

HaCaT or KB cells were grown in 10 cm dishes until confluent (HaCaT) or approximately 50% confluent (KB). Media was removed and cells washed three times with HBSS, and then 2ml of pre-warmed (37 °C) HBSS with 10mg/ml fatty acid-free BSA was added. The plates were then treated with UVB at various fluences or no UVB (sham). In some experiments the cells were treated with various concentrations of the metabolically stable PAF-R agonist N-methyl carbamyl PAF (CPAF) or 0.1% ethanol vehicle in HBSS with BSA. Other experiments used preincubation of HaCaT cells for one hour with 0.5mM each of the antioxidants N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and ascorbic acid (Vitamin C), before addition of CPAF or treatment with UVB. Cells were incubated for various times at (37 °C) and the supernatants removed. Cell numbers were determined using a particle counter (Coulter), and HaCaT cell numbers ranged from 12-19 × 106 cells/plate, and KB cells from 2-8 × 106 cells/plate.

Isolation and Measurement of MVPs

MVPs were collected from culture medium as previously described with slight modifications (20,21). In brief, cell culture medium was collected and centrifuged at 2000 g for 20 mins to remove cells and debris. Then, the supernatant was collected and transferred to a new tube for centrifugation at 20,000 g for 70 min. The resulted pellet was the isolated MVPs. The concentration of the MVP was detected by using a NanoSight NS300 instrument (NanoSight Ltd). Three 60-second videos were recorded of each sample with camera level and detection threshold set at 10. Temperature was monitored throughout the measurements. Videos recorded for each sample were analyzed with NTA software version 3.0 to determine the concentration and size of measured particles with corresponding standard error. The concentration of MVPs was described as the number of MVPs per mL of culture medium.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

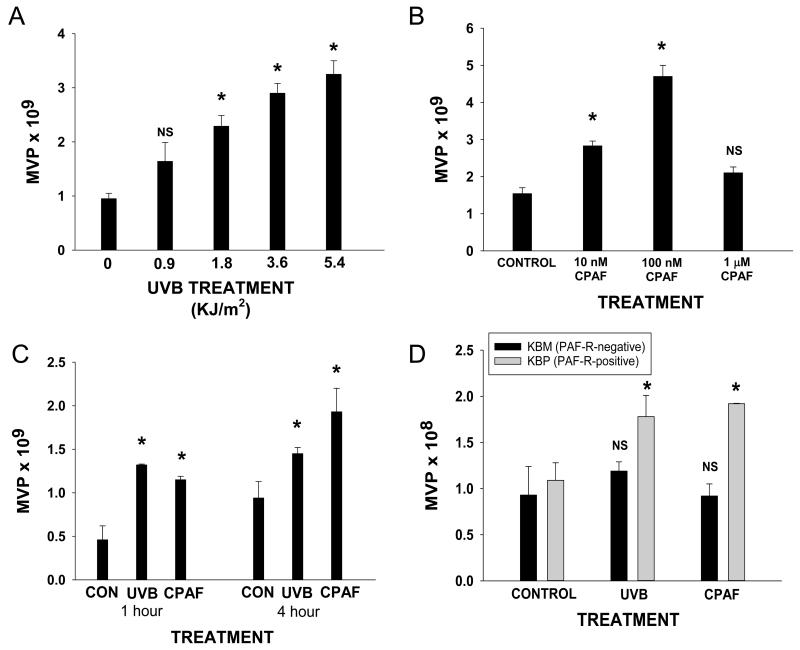

There has been renewed interest in MVP as potential signaling molecules. Though many stressors have been shown to generate MVP, the ability of UVB to induce their formation and release has not been defined. Thus, our first studies tested whether UVB irradiation can generate MVPs. As shown in Fig. 1A, UVB treatment of HaCaT cells resulted in the increased levels of MVP generation at 4 hrs. Of interest, we did not see consistent changes in levels of smaller exosomes in HaCaT cells following UVB (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Effect of UVB and CPAF on MVP release in HaCaT cells. HaCaT cells were either A) control (0) or UVB-irradiated at various fluences or B) control or various doses of CPAF. Four hours after treatment, the supernatants were removed and MVPs quantified as outlined in Methods. C) HaCaT cells were treated with 3.6 KJ/m2 UVB or 100 nM CPAF or control (CON), and were harvested 1 or 4 hrs post treatment. D). HaCaT cells were preincubated with 0.5 mM of N-aceytcysteine and 0.5 mM Vitamin C for one hour before treatment with 3.6 KJ/m2 UVB or 100 nM CPAF. The supernatants were removed and the MVP levels were measured 4 hrs later. The data presented are the mean ± SD. MVP numbers of duplicate values from a representative experiment of at least three performed. *Statistically (p<0.05) significant changes from control values. NS: not statistically significant from control values.

While the role of the PAF system in mediating various processes including UVB-induced acute inflammation as well as delayed systemic immunosuppression has been extensively studied (8,19,22), it is not known whether PAF is involved in UVB-induced MVP formation. Given that HaCaT cells express functional PAF-Rs (17), our first studies tested the ability of the non-metabolizable PAF-R agonist CPAF to generate MVP formation. As shown in Fig. 1B, CPAF treatment resulted in MVP formation in a dose-dependent manner. Of interest, high doses of CPAF (1 μM) actually resulted in a decreased response. This paradoxical effect of decreased PAF-R activation upon high levels of agonist has been previously described in other systems (23). The exact mechanism for this is unclear, but, could be due to competing (low- vs high-affinity) conformations of this G-protein coupled receptor, some of which could be linked to signal transduction pathways associated with MVP formation, with others exerting opposite effects. Moreover, we examined the effects of treatment time on the release of MVPs from HaCaT cells. As shown in Fig. 1C, there is MVP release at 1 hr with slightly increasing numbers of MVP measured at 4 hrs.

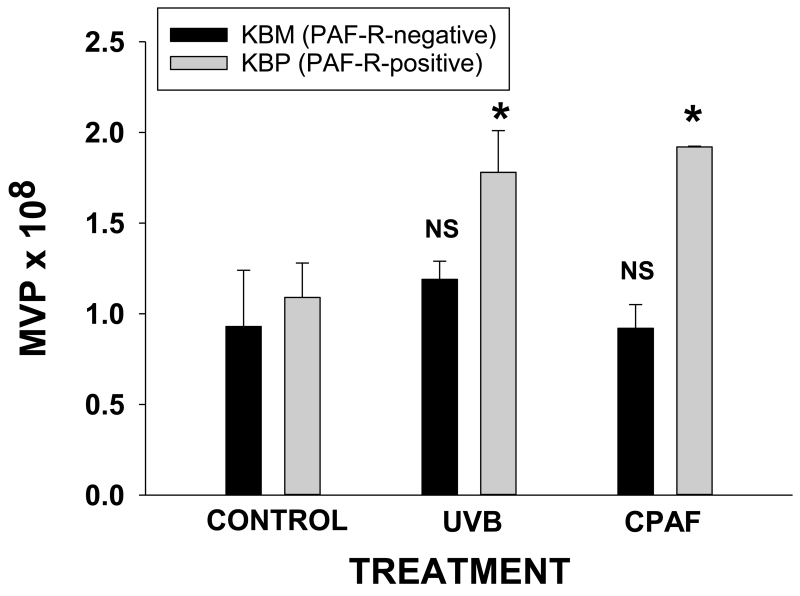

UVB-induced PAF agonists involve reactive oxygen species and can be blocked by antioxidants (7,19,22). To test if UVB-mediated MVP involves PAF agonists, we tested the ability of antioxidants can block UVB MVP production. As shown in Fig. 1D, pretreatment of HaCaT cells for 1h with 0.5 mM N-acetylcysteine and 0.5mM Vitamin C blocked MVP release induced by UVB, yet did not affect CPAF-mediated MVP release. Our next studies were designed to test if UVB-mediated MVP production involved the PAF system. To that end, we employed the KB cellular model of PAF-R-positive and −negative cell types (9,19). As shown in Fig. 2, UVB generated MVP formation only in PAF-R-positive KBP cells, but no appreciable differences were noted in MVP levels in PAF-R-negative KBM cells. Similarly, CPAF treatment only generated increased MVP production in KBP cells. These studies suggest that UVB-mediated generation of MVP formation in epithelial cells involves PAF-R signaling.

Figure 2.

Effect of UVB and CPAF on MVP release in KBP vs KBM cells. KB cells stably transduced with functional PAF-Rs (KBP) or empty vector (KBM) were treated with 100 nM CPAF or irradiated with 3.6 KJ/m2 UVB or control-treated. The supernatants were harvested at 4 hrs post-treatment. The data presented are the mean ± SD. MVP numbers of duplicate values from a representative experiment from at least three performed. *Statistically (p<0.05) significant changes from control values. NS: not statistically significant from control values.

In summary, the present studies indicate that UVB can generate MVP production and that PAF-R activation from endogenous PAF agonists appears to be an important event in mediating this process. Given that MVPs could potentially serve a messenger function, MVPs from epithelial cells could be one mechanism by which UVB can generate systemic signals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health grants HL062996 (JBT), HL098637 (YFC), and Veteran’s Administration Merit Award (JBT).

REFERENCES

- 1.Murphy GM. Ultraviolet radiation and immunosuppression. Br. J. Dermatol. 2009;161(Suppl 3):90–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leitenberger J, Jacobe HT, Cruz PD., Jr. Photoimmunology--illuminating the immune system through photobiology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2007;29:65–70. doi: 10.1007/s00281-007-0063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher MS, Kripke ML. Suppressor T lymphocytes control the development of primary skin cancers in ultraviolet-irradiated mice. Science. 1982;216:1133–1134. doi: 10.1126/science.6210958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ullrich SE. Mechanisms underlying UV-induced immune suppression. Mutat. Res. 2005;571:185–205. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walterscheid JP, Ullrich SE, Nghiem DX. Platelet-activating factor, a molecular sensor for cellular damage, activates systemic immune suppression. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:171–179. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Q, Yao Y, Konger RL, Sinn AL, Cai S, Pollok KE, Travers JB. UVB radiation-mediated inhibition of contact hypersensitivity reactions is dependent on the platelet-activating factor system. J. Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1780–1787. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao Y, Wolverton JE, Zhang Q, Marathe GK, Al-Hassani M, Konger RL, Travers JB. Ultraviolet B radiation generated platelet-activating factor receptor agonist formation involves EGF-R-mediated reactive oxygen species. J. Immunol. 2009;182:2842–2848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dy LC, Pei Y, Travers JB. Augmentation of ultraviolet B radiation-induced tumor necrosis factor production by the epidermal platelet-activating factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:26917–26921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travers JB, Edenberg HJ, Zhang Q, Al-Hassani M, Yi Q, Baskaran S, Konger RL. Augmentation of UVB radiation-mediated early gene expression by the epidermal platelet-activating factor receptor. J. Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:455–460. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao X, Ma X, Liu L, Wang J, Bi K, Liu Y, Fan R, Zhao B, Chen Y, Bihl JC. Cellular Membrane Microparticles: Potential Targets of Combinational Therapy for Vascular Disease. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2015;13:449–458. doi: 10.2174/1570161112666141014145440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orozco AF, Lewis DE. Flow cytometric analysis of circulating microparticles in plasma. Cytometry A. 2010;77:502–514. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camussi G, Deregibus MC, Bruno S, Cantaluppi V, Biancone L. Exosomes/microvesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication. Kidney Int. 2010;78:838–848. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratajczak J, Wysoczynski M, Hayek F, Janowska-Wieczorek A, Ratajczak MZ. Membrane-derived microvesicles: important and underappreciated mediators of cell-to-cell communication. Leukemia. 2006;20:1487–1495. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu S, Zhang W, Chen J, Ma R, Xiao X, Ma X, Yao Z, Chen Y. EPC-derived microvesicles protect cardiomyocytes from Ang II-induced hypertrophy and apoptosis. PLoS. One. 2014;9:e85396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Chen S, Ma X, Cheng C, Xiao X, Chen J, Liu S, Zhao B, Chen Y. Effects of endothelial progenitor cell-derived microvesicles on hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced endothelial dysfunction and apoptosis. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2013;2013:572729. doi: 10.1155/2013/572729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cicero AL, Delevoye C, Gilles-Marsens F, Loew D, Dingli F, Guere C, Andre N, Vie K, van NG, Raposo G. Exosomes released by keratinocytes modulate melanocyte pigmentation. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7506. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Travers JB, Huff JC, Rola-Pleszczynski M, Gelfand EW, Morelli JG, Murphy RC. Identification of functional platelet-activating factor receptors on human keratinocytes. J. Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:816–823. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12326581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li T, Southall MD, Yi Q, Pei Y, Lewis D, Al-Hassani M, Spandau D, Travers JB. The epidermal platelet-activating factor receptor augments chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in human carcinoma cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:16614–16621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marathe GK, Johnson C, Billings SD, Southall MD, Pei Y, Spandau D, Murphy RC, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, Travers JB. Ultraviolet B radiation generates platelet-activating factor-like phospholipids underlying cutaneous damage. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:35448–35457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crescitelli R, Lasser C, Szabo TG, Kittel A, Eldh M, Dianzani I, Buzas EI, Lotvall J. Distinct RNA profiles in subpopulations of extracellular vesicles: apoptotic bodies, microvesicles and exosomes. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2013:2. doi: 10.3402/jev.v2i0.20677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witwer KW, Buzas EI, Bemis LT, Bora A, Lasser C, Lotvall J, Nolte-’t Hoen EN, Piper MG, Sivaraman S, Skog J, Thery C, Wauben MH, Hochberg F. Standardization of sample collection, isolation and analysis methods in extracellular vesicle research. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2013:2. doi: 10.3402/jev.v2i0.20360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Travers JB, Berry D, Yao Y, Yi Q, Konger RL, Travers JB. Ultraviolet B radiation of human skin generates platelet-activating factor receptor agonists. Photochem. Photobiol. 2010;86:949–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2010.00743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nilsson G, Metcalfe DD, Taub DD. Demonstration that platelet-activating factor is capable of activating mast cells and inducing a chemotactic response. Immunology. 2000;99:314–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]