Abstract

John W. Saunders, Jr. made seminal discoveries unveiling how chick embryos develop their limbs. He discovered the apical ectodermal ridge (AER), the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA), and the domains of interdigital cell death within the developing limb and determined their function through experimental analysis. These discoveries provided the basis for subsequent molecular understanding of how vertebrate limbs are induced, patterned, and differentiated. These mechanisms are strongly conserved among the vast diversity of tetrapod limbs suggesting that relatively minor changes and tweaks to the molecular cascades are responsible for the diversity observed in nature. Analysis of the pathway systems first identified by Saunders in the context of animals displaying limb reduction show how alterations in these pathways have resulted in multiple mechanisms of limb and digit loss. Other classes of modification to these same patterning systems are seen at the root of other, novel limb morphological alterations and elaborations.

Introduction

In 1946, after returning from service in the pacific theater of World War II, John W. Saunders Jr. returned to Johns Hopkins University to complete his PhD thesis. His original focus was on how feather buds develop and are patterned in the ectoderm but it was his dissertation work detailing the apical ectodermal ridge (AER) and its role in limb growth and differentiation which was his first seminal contribution. First identified as a darkly staining structure when Nile Blue was added to the embryo, he found the AER to be required for outgrowth of the limb bud. This discovery provided the first insights in the establishment of the proximodistal axis of the limb and later providing the basis for the progressive model of limb development. When he presented this work in 1948, it was heralded as the greatest discovery in 50 years (Saunders, 2002). As he continued to use Nile Blue to stain chick embryos, he noticed that certain regions of the limb stained more darkly than others. Embryonic manipulation of these regions led first to the discovery of the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) which when transplanted to the anterior limb bud results in a mirror duplicated limb (Saunders and Gasseling 1968). The identification of the ZPA was a watershed moment in developmental biology that characterized a classical organizing center as well as informed the patterning of the anteroposterior limb axis. With the realization that Nile Blue marks cells in the process of dying (through the mechanism we now refer to as apoptosis), Saunders was drawn to investigate the role cell death plays in normal limb development. This interest led to the identification of several distinct zones of cell death in the limb bud, including the discovery that increased cell death removes the interdigital tissue to result in morphologically free digits (Saunders and Gasseling, 1962).

John Saunders’ superb embryological skills and keen observations provided much of the experimental groundwork that would later result in the molecular understanding of how vertebrates develop, grow, and pattern their limbs. The implications of these discoveries, however, reach beyond the understanding of chick embryonic limbs (or vertebrate limbs in general); John Saunders’s seminal discoveries also lie at the center of our current understanding of how these patterning mechanisms have been altered throughout evolution to result in the vast array of limbs observed amongst tetrapods.

The paired appendages of vertebrates have been shaped by natural selection to provide the organism with optimal methods for locomotion. Given the myriad methods of movement observed across the vertebrate clade, it’s not surprising that the fins and limbs of these animals have evolved multiple forms reflecting their specific functions. To attain these multiple forms, the developmental programs that build them need to be altered to shape the limbs and appendages appropriate for the animal’s lifestyle. In this review, we summarize the growing body of literature that describes several mechanisms of limb evolution via alterations in patterning, and place these findings in the context of the discoveries of John W. Saunders, Jr.

Basic limb development

While limb patterning mechanisms are discussed at greater depth in other chapters of this volume, some key aspects are highlighted here as a context for understanding the evolutionary modifications that follow below. Despite the vast array of tetrapod limb adaptions, which allow for running, grasping, swimming, and flying, the developmental programs to build a limb are remarkably conserved. The limb bud first forms as an outgrowth of mesenchyme from the somatoplueral lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) that is enveloped by an ectodermal epithelium. This outgrowth first emerges after three days of development in the chick and nine days in the mouse. The distal tip of the limb bud ectoderm forms a columnar epithelium, which comprises the AER. Experimental studies have revealed that the AER plays an important role in limb development; removal of this structure at progressively later stages results in the loss of progressively more distal structures (Saunders, 1998). Following induction of the AER, the limb bud grows outward and begins to display an anterior-posterior polarity.

Much investigation has been devoted to the molecular signals and gene regulatory networks that drive these morphological events in the embryo (Figure 1A). In amniotes, limb initiation begins with localized epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) in the LPM driven by the activities of Tbx5 (forelimb) or Tbx4 (hind limb) and Fgf10 (Gros and Tabin, 2014). Following this mesodermal EMT, Fgf10 signals to the overlying ectoderm (Ohuchi et al., 1997) which induces it to start secreting Fgf4, Fgf8, Fgf9, and Fgf17. These factors then signal back to the underlying mesenchyme (Lewandoski et al., 2000; Mariani et al., 2008). This reciprocal signaling sets up a positive feedback loop that drives proliferation of the underlying mesenchyme and results in the outgrowth of the bud (Laufer et al., 1994; Niswander et al., 1994). Additionally, this feedback loop has the added function of keeping the mesenchyme under the influence of Fgf signaling undifferentiated. The region of distal proliferative mesenchyme is referred to as the progress zone (Summerbell et al., 1973). However proximodistal patterning (discussed more fully elsewhere in this volume) has turned out to be more complicated than that was conceptualized in early models. More recent studies suggest that proximodistal patterning involves some level of organization in the early limb (Barna and Niswander, 2007; Dudley et al., 2002). This early pattering is thought to result from the activity of countervailing signals from the AER and flank (Cooper et al., 2011; Mariani et al., 2008; Roselló-Díez et al., 2011), as well as an intrinsic timing mechanism within mesenchymal cells operating in the more distal limb segments (Saiz-Lopez et al., 2015).

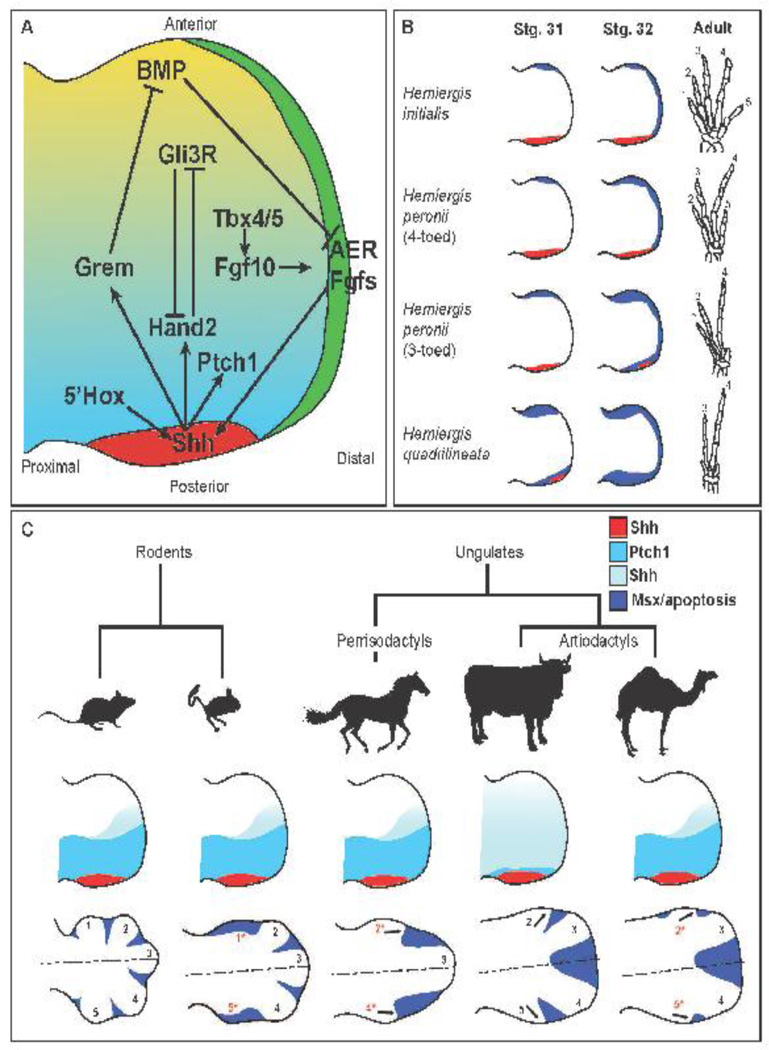

Figure 1.

Schematics of signaling cascades in general tetrapod limb development and alterations that result in digit loss. (A) Major signaling factors and their spatial relationships in the developing tetrapod limb. (B) Schematic of digit loss in Australian skink species showing Shh expression in red and Msx expression in blue of stage 31 and 32 autopods and the resulting adult hind foot skeletons. Adapted from (Shapiro et al., 2003) (C) Representative mammalian species and their respective autopod patterning. Silhouettes of the mouse, jerboa, horse, cow, and camel (left to right) and their relative phylogeny. Limb bud schematics showing Shh expression in red and Ptch1 expression in light blue. Graded blue depicts anterior extent of Shh signaling. Autopod schematics below depict Msx expression or apoptosis (cow). Developing digits are labeled one through five. Digits in red with asterisks are digits that get sculpted away by post-patterning apoptosis. Arrows in the autopods of the cow and the camel indicate angle of digit growth. Dotted lines indicate the weight-bearing axis of the limb for the respective animal.

At the time of limb induction the limb bud mesenchyme is already prepatterned such that it is polarized along the anterior-posterior axis. This includes reciprocal gradients of the transcription factors Hand2 and Gli3 (i.e.(Welscher et al., 2002)) and the vector expression of several 5’ HoxD genes (Zakany et al., 2004). A key consequence of this early prepatterning is the activation in the posterior limb of Sonic hedgehog (Shh), the active agent responsible for the phenotypes observed in Saunder’s ZPA grafts (Riddle et al., 1993). While the full understanding of the localization of Shh expression to the extreme posterior margin is still lacking, it involves the direct activity of Hand2 and 5’ Hoxd genes and is opposed by Gli3 activity. Subsequently, Shh signaling feeds back to induce both Hand2 and HoxdD expression. Most important is the posterior to anterior graded inhibition of Gli3 processing resulting in high Gli3 activator in the posterior and high Gli3 repressor (Gli3R) in the anterior. Once this signaling gradient is established, it is reinforced by the mutual repression between Hand2 and Gli3R (Welscher et al., 2002). The Shh-dependent gradient of Gli3R activity is the critical determinant of anterior-posterior morphological asymmetry in the limb. In addition, Shh signaling is essential for activating a second, late phase of HoxD expression that patterns the distal limb (Nelson et al., 1996; Tarchini and Duboule, 2006). Distinct regulatory regions control the two phases of HoxD gene limb expression. The early phase is controlled by elements located telomeric to the HoxD cluster and is required for formation of the more proximal elements of the limb. The late phase expression is regulated by centromeric elements and is required for the formation of the autopod (Andrey et al., 2013). Following activation of Shh via Hox and Hand2, its expression is maintained by Fgfs from the AER. In turn, Shh induces the expression of the BMP antagonist Gremlin to prevent BMP-mediated inhibition of Fgf production in the AER (Capdevila et al., 1999; Laufer et al., 1994; Niswander et al., 1994; Zuniga et al., 1999). This gene-regulatory loop has the purpose of maintaining Fgf and Shh signaling at the distal end of the limb as it grows out but allows for the attenuation and quenching of these activities in more proximal regions (Scherz et al., 2004; Verheyden and Sun, 2008).

These mechanisms are not restricted to amniotes, amphibians use the same molecular program to build their limbs with posterior expression of Shh (Endo et al., 1997) and distally expressed Fgfs (Christen and Slack, 1997; Keenan and Beck, 2016). In some species (i.e. most urodeles, the direct developing frog Eleutherodactylus coquí, and the marsupial Monodelphis dometica), however, Fgf expressing cells of the ectoderm do not form a morphological ridge at the distal tip of the bud (Doroba and Sears, 2010; Gross et al., 2011; Richardson et al., 1998). This suggests that the columnar structure observed in amniotes is not required for its patterning functions.

Evolution in tetrapod limbs

As fundamental as the signaling criteria discovered by John Saunders have proven to be for understanding developmental mechanisms, they have played equally critical roles in limb evolution. The gene regulatory networks that build the paired appendages of vertebrates are highly conserved with many genes playing similar roles in the fin of zebrafish as they do in the wing of a chicken, reflecting the homology of these structures. While the critical molecular players have been conserved, changes in the regulatory landscape that control the expression of molecules in the limb gene regulatory network have likely driven the fin-to-limb transition (Gehrke and Shubin, 2016; Tanaka, 2016). Subsequent to that transition, however, the basic structures of the tetrapod limb have become highly canalized. Nonetheless, recent investigations have demonstrated that the diversity of tetrapod limbs has, in large measure, been generated through further alterations in the regulation of the same set of patterning genes.

Evolutionary loss and reduction of limb structures

The specialization of tetrapod limbs have resulted in adaptations for aquatic, aerial, fossorial, and cursorial lifestyles. Natural selection imposed by these lifestyles has resulted in limb element reductions/losses as well as elaborations in the tetrapod limb. The question that lies at the center of evolutionary developmental biology is how these different forms are generated using the genes common to all animals within a given group while still conforming with developmental constraint? One common feature in the evolution of the tetrapods is several instances of digit reduction or loss. Given what is known about limb patterning, including insights gleaned from hypermorphic and loss-of-function alleles of the various genes known to be included in the process, various hypotheses can be generated to explain the molecular mechanisms that might underlie digit loss over evolutionary history. Saunders’s original ZPA transplantation experiments indicate that this signaling center, and its proximal ligand Shh, are critical for determining the number of digits in the limb. Thus, one possible mechanism for specifying fewer digits would be attenuation of the level or duration of Shh expression. Reducing the sensitivity to the Shh ligand would have the same effect. Alternatively, an organism could generate a full set of digits during embryogenesis through normal Shh activity and later sculpt them away. Perhaps unsurprisingly, examples of all three of these possibilities can be found in nature.

Species of Australian skink (a type of lizard) in the genus Hemiergis contain several closely related species that have a range of digit numbers from two to five. Investigations of the chondrogenic patterns of the digits between different species revealed that the loss of digits is not due to heterochronies in autopod development nor truncations in the digit skeletal programs (Shapiro, 2002). Instead the digit loss in these skinks correlated most significantly with a reduction in the duration of Shh expression in the ZPA (Shapiro et al., 2003) (Figure 1B). This finding suggested that lizards with fewer digits have attenuated sonic signaling in the developing autopod, which fails to broaden the hand plate thereby resulting in the formation of fewer digits. This interpretation is supported by experimental evidence in the more tractable genetic models of the mouse and chick. Lineage tracing and inducible alleles revealed that the Shh producing cells are required for the formation of digits two through five in the mouse (Harfe et al., 2004) and that more posterior digits require longer durations of Shh signaling in order to form them (Scherz et al., 2007). As in skinks, the order in which digits are lost followed truncation of Shh exposure in the mouse is not a single posterior-to-anterior progression, but rather reflects the inverse of the order in which the skeletal elements form (Zhu et al., 2008) a phenomenon first noted in experimental manipulations with amphibians (Alberch and Gale, 1983).

The underlying genetic basis for the Shh attenuation observed in the digit reduced Australian skinks remains to be determined. Certainly one plausible mechanism is alterations in the transcriptional control of Shh via cis-regulatory modules. Interestingly, the limb expression of Shh is controlled by a single cis regulating region, termed the ZRS (ZPA regulatory sequence), which is located 1 Mb away from the Shh transcription start site in intron 5 of the Lmbr1 gene (Lettice et al., 2003). While there are many other enhancers that regulate Shh expression in other tissues, the ZRS is solely responsible for limb expression as loss of the ZRS results in appendages with only a single skeletal element per limb segment in mice (Sagai et al., 2005) and in chickens (Maas et al., 2011; Ros et al., 2003). This enhancer and its location within the Lmbr1 gene is remarkably conserved; it is found in the same gene with a high degree of sequence conservation in all vertebrate clades with paired appendages including chondrichthyans and teleosts (reviewed in (Gehrke and Shubin, 2016).

One of the most obvious examples of digit evolution is seen in the ungulates. These animals have adapted to a cursorial lifestyle, which requires a streamlined body plan for running. Natural selection has resulted in the elongation of distal skeletal elements with terminal hoofs as well as reductions in the lateral digits. These hoofed mammals consist of two groups: the even toed artiodactyls (e.g., cattle, deer, pigs, sheep, camels, etc.) and the odd-toed perissodactyls (horses, tapirs, and rhinoceroses) (Figure 1C). Artiodactyls possess paraxonic limbs meaning that the weight-bearing axis runs between digits three and four whereas the mesaxonic limbs of perissodactyls bear weight on their middle digit. Both these lineages are derived from a pentadactyl ancestor that was presumably mesaxonic and therefore must have altered the basic patterning mechanisms of the autopod to develop fewer digits and shift the axis of symmetry. Contrary to the example of the Australian Skinks above, Shh expression in these groups of animals is not reduced in time or in space suggesting that either changes in the Shh signaling cascade are downstream of the ligand or another mechanism is in place. In the mouse, Ptch1 is upregulated in the posterior region of the limb bud as it is a direct transcriptional target of Shh signaling. Ptch1 is the Shh receptor and, as such, serves to transduce signaling. However, in addition, when up-regulated it serves a second function as a sink for free Shh ligands.

In bovine embryos, however, Ptch1 is not upregulated in the posterior region of the limb bud mesenchyme (López-Ríos et al., 2014). The failure to induce Ptch1 in the posterior region allows Shh signaling to extend further to the anterior as there is less Ptch1 to sequester the Shh protein. This, in turn, results in a non-polarized distal limb bud that lacks digit one (López-Ríos et al., 2014). Consistent with these observations, a cis-regulatory element, bound by Gli3, is found in the Ptch1 locus of the mouse that drives specific expression in the posterior limb mesenchyme. In the cow, however, this regulatory module is lost so that Shh does not induce its expression to a level at which it functions to sequester the ligand (López-Ríos et al., 2014). As expected, when looking at other artiodactyls, it was found that pigs also fail to upregulate Ptch1. Surprisingly, however, camels do have broad expression of Ptch1 in the posterior limb bud (Cooper et al., 2014). Therefore, this attenuation of Shh sequestration does not explain digit loss in all artiodactyls let alone the ungulates in general (Figure 1C).

A clue to additional mechanisms of mammalian digit loss came from examining species of jerboas, small rodents that inhabit the deserts of Asia and Africa. Jerboas are the sister clade to mice but have undergone several adaptations for their environment. The extent of their morphological adaptation varies among jerboa species, but includes a bipedal posture along with elongation of the distal bones and a loss of digits one and five in their hind limbs. Ptch1 is broadly expressed in the posterior mesenchyme of the jerboa hind limb, bud ruling out the mechanism of altering the patterning functions of Shh signaling in the autopod seen in cows. Instead, during the point when cells in the autopod are proliferative, there is an upregulation of Msx2, a pro-apoptotic gene in the limb, and a resulting increase in cell death within the mesenchyme that would otherwise contribute to the lost digits (Cooper et al., 2014). This presents a second mechanism for the evolutionary loss of digits in mammals where the autopod is patterned similar to pentadactyl species but both preaxial and postaxial digits are sculpted away prior to chondrocyte condensation but after anterior posterior patterning (Cooper et al., 2014). This same “post-patterning sculpting” mechanism was also found to occur convergently in horses. If it were not for the data on camels cited above, an attractive hypothesis would have been that the loss of the Gli3 response elements in the Ptch1 locus occurred at the base of artiodactyl evolution and the development of the mesaxonal limb. This, however, cannot be the case. The camel, an artiodactyl with mesaxonic limbs, exhibits the same Ptch1 upregulation in the posterior limb mesenchyme as the horse, jerboa, and mouse. Further, localized apoptosis occurs in the primordial of digits two and five to generate the mature two-toed autopod (Cooper et al., 2014) (Figure 1C). Camels are the earliest branching artiodactyls (Meredith et al., 2011). As such, alterations to the Shh dependent autopod patterning seen in cows and pigs likely evolved in the artiodactyl lineage after the camels split off. This suggests that the mesaxonal configuration as well as digit loss must have arisen as parallel adaptations within the two branches of the clade.

Evolutionary digit loss is not restricted to reptiles and mammals. Several species of birds have lost digits over their evolution, most commonly in the ratites. Ratites are a paraphyletic group of large flightless birds found throughout the southern hemisphere. These animals have generally adopted a cursorial lifestyle and accordingly lost the ability to fly along with their adaptations to this mode of locomotion. Surprisingly, recent phylogenetic evidence supports the hypothesis that flight was lost multiple times in this clade suggesting that the hallmarks of longer, more robust hind limbs and reduced or missing forelimbs are due to convergent evolution (Baker et al., 2014; Harshman et al., 2008). Further, these adaptations have also resulted in digit loss among the limbs of these birds. For example, the Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) and the Cassowary (Casuarius spp.) possess three digits on their hind limbs but only a single digit on their forelimbs. Conversely, the Ostrich (Struthio camelus) retains the ancestral number of three digits on its wing but has reduced the number of digits on its hind limb to two. In all cases of digit loss among this group, digit three is retained, hypothesized to be due to developmental constraint (de Bakker et al., 2013) meaning that it is isn’t possible to completely do away with digits without disrupting the molecular patterning mechanisms required for other structures such as robust hind limbs. Perhaps due to this constraint, the primordia of the lost digits to persist late into embryogenesis where they are marked by Sox9 expression followed by differentiation into chondrocytes but a failure to ossify (de Bakker et al., 2013). What happens to these digits to stop them from forming bone? Presumably they are sculpted away, perhaps in a similar fashion as seen in the horse and jerboa described above but at much later developmental time point. It’s tempting to assume that the loss is due to wholesale reduction in the size of the overall organ as would be the case for the wings of the Emu and the Cassowary, however, similar digit persistence followed by late loss occurs in the hind limb of the Ostrich which is increased in size and mass. Together this suggests that a different mechanism is at work in the ratites to prune digits from the autopod that is yet to be unraveled.

Finally, it’s worth noting that differences in digit numbers among closely related species is also found within amphibians. There are three extant species of Amphiuma: the Three-toed amphiuma (A. tridactylum), the Two-toed amphiuma (A. means), and the One-toed Amphiuma (A. phoeleter). The limbs of these animals are massively reduced to the point that they’re mostly vestigial. But despite their size and apparent uselessness, their limbs still retain marginal regenerative ability (Morgan, 1903). The developmental basis that results in different digits between species of Amphiuma is not understood but it may yet be a novel mechanism unlike those described for reptile, mammals, and birds above. Salamanders differ from all other tetrapods in that digit condensation proceeds in the preaxial to postaxial direction such that the anterior digits form before the posterior ones. This is in contrast to other tetrapods (including anurans) which form posterior digits before anterior ones (Alberch and Gale, 1983; Shubin and Alberch, 1986). This difference has led some evolutionary biologists to hypothesize that salamanders lost digits then re-evolved them and that the preaxial digits are ancestrally digits three and four (Wagner et al., 1999). This is unlikely as no fossils have been found showing loss and re-emergence of digits in salamander ancestors (Fröbisch and Shubin, 2011). More convincingly, recent phylogenies of salamanders put species with reduced limbs and lost digits in more derived lineages rather than basal ones (Bonett et al., 2009; Roelants et al., 2007; Zhang and Wake, 2009). There is however, a clear correlation with regenerative capacity and preaxial digit development which is yet to be understood (Fröbisch et al., 2015).

Some tetrapods have taken appendage reductions to the extreme by eliminating a limb completely, a phenomenon that has occurred independently in all tetrapod groups. Most snakes are completely limbless but species of pythons and boas develop vestigial pelvic girdles and corresponding limb buds are easily observed in their embryos. These buds fail to produce the full limb however, resulting in a small pelvis and short femur. Earlier work suggested that the limb fails to grow because of a degeneration of the AER resulting in the lack of Fgf and Shh production breaking the ectodermal-mesenchymal Fgf positive feedback loop (Cohn and Tickle, 1999). Recently, however, it was been discovered that pythons do initially induce Shh and Fgf8 in early hindlimb buds, only transiently and Shh expression is reduced due to degeneration of the ZRS (Kvon et al., 2016; Leal and Cohn, 2016). Further analysis revealed that a conserved Ets1 binding site in the ZRS is lost in all examined snake genomes and restoration of this site is sufficient to rescue the full activity of the ZRS (Kvon et al., 2016). These findings reopen the question of why the limb is lost when both Shh and Fgf are expressed in the initial limb bud? It’s possible that other cis-regulatory changes are involved. For example, expression of Tbx5 in both the hindlimb buds and external genitalia of lizards and mice is driven by the HLEB enhancer. However, in snakes, this enhancer is only active in the genital tubercle (Infante et al., 2015). Interestingly, the cis-regulatory modules that control the early and late phase Hox expression in tetrapod limbs is conserved in pythons suggesting that they retain the ability to properly pattern the proximodistal axis of their diminutive limbs (Leal and Cohn, 2016).

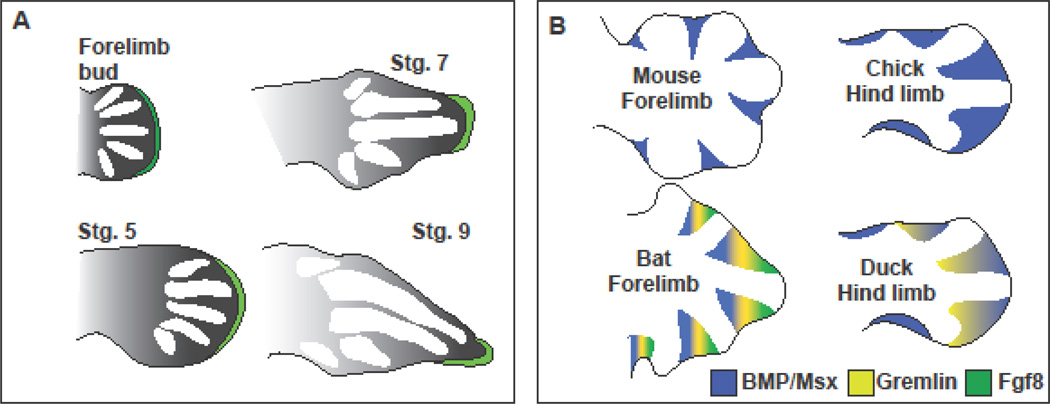

Alterations and reductions of the pelvic girdle are not restricted to reptiles, cetaceans have massively reduced their pelvic girdles as they evolved from land dwelling to marine mammals. Analysis of spotted dolphin (Stenella attenuatta) embryos revealed that they too produce hind limb buds, which are eventually lost by later stages. The dolphin hind limb initially forms an AER and expresses Fgf8 but neither the structure nor the gene expression is maintained. This, along with the failure to induce Shh in the ZPA, results in severely reduced hind limb skeleton (Thewissen et al., 2006). Interestingly, altered Fgf signaling from the AER is also thought to be the developmental basis that underlies aspects of the morphology of the pectoral flipper of dolphins. The AER initially extends along the anterior posterior axis of the forelimb bud in the developing dolphin embryo. However, during the formation of the digits, the AER is maintained for a relatively longer duration than in land developing tetrapods, but it becomes continually restricted to the distal most region of the limb bud which results in digits two and three becoming markedly longer than the others resulting in a triangular shaped flipper (Richardson and Oelschläger, 2002) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Schematics depicting the alterations in the development of dolphin flippers, bat wings, and duck feet. (A) Dolphin flipper development from limb bud through Stage 9. Green depicts the AER and the graded black is the presumed influence of Fgf signaling. Developing digits are shown in white. Modified from (Richardson and Oelschläger, 2002). (B). Patterns of signaling molecules in animals with altered interdigital webbing. BMP and Msx expression is in blue, Gremlin expression in yellow, and Fgf8 expression in green.

Gene expression and morphological analyses suggest a molecular mechanism for the loss of limbs, but what is the genetic basis for the observed altered gene expression? Species of stickleback fish have both marine and freshwater forms, which differ in the presence or absence of pelvic spines, respectively (the pelvic spine being a modified pectoral fin, the homologue of the hind limb). Quantitative trait analysis revealed that loss of the homeobox transcription factor pitx1 expression in the pelvic girdle is responsible for the loss of these structures (Shapiro et al., 2004). Control of pelvic pitx1 expression is via a highly conserved enhancer that drives expression specifically in the pelvis, which is repeatedly lost in freshwater species (Chan et al., 2010). The remnant of the pelvis in stickleback fish missing their pelvic spans and in mice deficient for pitx1 in the limb is asymmetric, likely due to a small amount of compensation by the left-right patterning gene pitx2 on the left. A similar signature of a larger pelvic remnant in the left versus right in manatees suggests that limb-specific loss of Pitx1 may underlie loss of hind limbs. It’s interesting to speculate whether similar mechanisms are responsible for the loss of hind limbs in the sirenidae; species of large salamanders with reduced forelimbs and absent hind limbs.

Adaptations that augment the tetrapod limb

While many of the most dramatic tetrapod limb modifications involve the loss of structures, there are striking examples of elaborations as well. Changes to the developmental limb patterning programs that result in major additions or transformations of structures of existing ones are by comparison more rare than reductions or losses, but nonetheless have occurred with the evolution of tetrapods. Perhaps the most salient example of this is the alterations to the forelimb of bats that has allowed for powered flight. The wings of bats are primarily supported by extremely elongated phalanges of digits three, four, and five of the forelimb. This extreme elongation occurs after the skeletogenic precursors condense and differentiate into chondrocytes as the digits of both bat and mouse embryos are initially equal in length (Sears et al., 2006). Comparisons between the mouse and the Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) revealed that there is a high correlation between the number of proliferating chondrocytes at birth and proximal bone length of the adult (Rolian, 2008). Consistent with this observation, the elongated digits in the bat exhibit increased chondrocyte proliferation along with a lengthening of the hypertrophic chondrocyte zone relative to mice (Sears et al., 2006). The hypertrophic zone has been shown to contribute the most to overall bone length (Wilsman et al., 1996), which gives support to the conclusion that the increased hypertrophic zone of these digits are responsible for their elongation. One contributing factor underlying these adaptations on the bat forelimb is likely to be increased signaling via Bmp2, as inhibition via the antagonist Noggin results in shortened hypertrophic zones and Bmp2 is expressed at a somewhat higher level in the developing bat forelimb digits relative to both the bat hind limb and mouse forelimb digits. Although multiple other Bmp ligands are co-expressed in the same domain, they do not appear to be upregulated in the same manner (Sears et al., 2006). Moreover, Bmp2 is not likely to be the only factor involved in elongating the digits of the bat. The paired homeobox gene Prx1 is expressed in the craniofacial mesenchyme, somites, and limb lateral plate mesoderm and mice lacking this gene have severe craniofacial defects and extremely shortened limbs (Martin et al., 1995). Comparisons between the regulatory regions of Prx1 between bats and mice revealed potential enhancers that drive its expression in the limb. Removal of these enhancers do not significantly alter the length of the forelimb but replacing the mouse enhancer with that of the bat results in a modest and transient increase in bone length (Cretekos et al., 2008). These data suggest that multiple pathways have evolved in the bat lineage to derive the elongated digits required to support the wing during flight and that it is likely that additional critical pathways still await elucidation.

Perhaps the most obvious modification of the limb in bats is the webbing of their wings. John Saunders discovered that the webbing between the digits of most tetrapods is sculpted away via apoptosis (Saunders and Gasseling, 1962), which was later found to be due to upregulation of Bmp signaling (Zou and Niswander, 1996). However, in ducks where the webbing is retained between the digits, Bmp is still highly expressed but is counteracted by an increasing the expression of the BMP antagonist Gremlin (Merino et al., 1999) (Figure 2B). A similar mechanism is at work in the bat interdigital webbing. Bmp2/4/7 are expressed in the interdigital space of the bat as is the antagonist Gremlin. Moreover, Fgf8 (which opposes the activity of Bmp signaling in the dorsal limb) is also upregulated in this tissue. The concomitant expression of Fgf8 and Gremlin serves to block apoptosis at two nodes, ensuring that the wing membrane persists throughout development (Weatherbee et al., 2006) (Figure 2B).

Similar to the elongation in the digits of the bat, jerboas, mentioned above, also have also elongated their limb bones in their evolution of a bipedal posture. The three-toed jerboa has extremely elongated metatarsals in the hind limb. Similar to what is observed in the bat, the metatarsal of the jerboa has a markedly larger hypertrophic chondrocyte zone when compared to the mouse (Cooper et al., 2013). Further, Cooper and colleagues found that the chondrocytes in the hypertrophic zone go through three phases of hypertrophy dependent on Igf1 and the third phase of hypertrophy contributes to the greatest increase in bone length. Certainly Bmp and Igf1 signaling could both be playing a role in augmenting bone length either independently or in concert. In the jerboa, as in the bat, the key genetic changes that result in the observed changes in gene expression in these species await discovery.

Open Questions

The molecular era of developmental and evolutionary biology has helped elucidate several mechanisms that have altered the basic form of the tetrapod limb. It’s no surprise, however, that many questions remain. In particular, the molecular control of timing, particularly that determining when tetrapod limbs develop in various species, is poorly understood. One exception is the Emu, which has a marked delay in the development of the forelimb relative to chick embryos (Nagai et al., 2011). The transcription factor Tbx5 is required for forelimb development as its deletion in the forelimb lateral plate mesoderm results in mice lacking their forelimbs (Rallis et al., 2003). Expression analysis of Tbx5 expression in Emu embryos revealed a delay in forelimb expression until shortly before their forelimb buds form suggesting a mechanism whereby the delay in forelimb growth is due to delayed Tbx5 expression. Restriction of Tbx5 expression to the forelimb is achieved via regulatory elements that are responsive to broadly expressed activators but subject to dominant repression by caudally expressed Hoxc9 (Minguillon et al., 2012; Nishimoto et al., 2014). Therefore, this combinatorial regulation must be altered in the Emu, either at the level of Hox expression or the Tbx5 regulatory elements to result in its delayed expression.

Emus are not the only tetrapods that exhibit a heterochrony in the development of their forelimbs and hind limbs. Marsupials develop and differentiate their forelimbs well before their hind limbs, as they are needed to crawl to the pouch following birth. This heterochrony between fore- and hindlimb development observed in marsupials has been investigated in the gray short-tailed opossum Monodelphis domestica. Gene expression analysis has revealed that following initiation of both fore- and hindlimb buds, Fgf8, Fgf10, and Shh are all expressed earlier in the forelimb (Dowling et al., 2016; Keyte and Smith, 2010). Additionally, cells in the forelimb expresses more Igf1 (Sears et al., 2012), proliferate more (Beiriger and Sears, 2014), and undergo precocious chondrogenesis and ossification (Sears, 2009). However, the underlying genetic mechanisms responsible for changes in gene expression between fore- and hindlimbs of marsupials are not understood. It could be altered Hox gene responsiveness or as yet another mechanism to be discovered. Similar questions await answers in amphibians as well. Direct developing frogs like the coquí develop limb buds at a similar stage and mechanism as amniotes do (Elinson and del Pino, 2012; Gross et al., 2011; Hanken et al., 2001). What mechanisms have evolved in the coquí that allows it to grow limbs so early in embryogenesis where ancestral frogs develop limbs during metamorphosis? Answers to these questions and others will further broaden our knowledge on how tetrapods have evolved the diversity of limbs observed in nature.

Concluding remarks

Even with the many questions remaining to be answered, it’s clear that the discoveries of John Saunders and colleagues over his career continue to provide the basis of our understanding of limb development. These discoveries also serve as the foundation for understanding the molecular mechanisms that underlie limb evolution. Digit loss in artiodactyls and Australian skinks is the result of alterations in the ZPA. Loss of hind limbs in the dolphin is attributed to the degradation of the AER. The webbing of duck feet and bat wings is the result of changes in cell death within the limb. John Saunders’s natural curiosity, keen observations, and excellent experimental technique has made it possible for scientists to begin to understand molecular evolution of limb form and function. We are all grateful that John W. Saunders Jr. returned to Johns Hopkins to complete his Ph.D.

HIGHLIGHTS.

John W. Saunders, Jr. made seminal discoveries unveiling how chick embryos develop their limbs. These discoveries provide the basis for molecular understanding of how vertebrate limbs are induced, patterned, and differentiated.

These findings, in turn, have informed and guided efforts to understand limb evolution, including cases of limb and digit loss.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alberch P, Gale EA. Size dependence during the development of the amphibian foot. Colchicine-induced digital loss and reduction. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1983;76:177–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrey G, Montavon T, Mascrez B, Gonzalez F, Noordermeer D, Leleu M, Trono D, Spitz F, Duboule D. A switch between topological domains underlies HoxD genes collinearity in mouse limbs. Science. 2013;340:1234167. doi: 10.1126/science.1234167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AJ, Haddrath O, McPherson JD, Cloutier A. Genomic support for a moa-tinamou clade and adaptive morphological convergence in flightless ratites. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:1686–1696. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barna M, Niswander L. Visualization of cartilage formation: insight into cellular properties of skeletal progenitors and chondrodysplasia syndromes. Dev Cell. 2007;12:931–941. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiriger A, Sears KE. Cellular basis of differential limb growth in postnatal gray short-tailed opossums (Monodelphis domestica) J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2014;322:221–229. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.22556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonett RM, Chippindale PT, Moler PE, Van Devender RW, Wake DB. Evolution of gigantism in amphiumid salamanders. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila J, Tsukui T, Rodríquez Esteban C, Zappavigna V, Izpisúa Belmonte JC. Control of vertebrate limb outgrowth by the proximal factor Meis2 and distal antagonism of BMPs by Gremlin. Mol Cell. 1999;4:839–849. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80393-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YF, Marks ME, Jones FC, Villarreal G, Shapiro MD, Brady SD, Southwick AM, Absher DM, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Myers RM, Petrov D, Jónsson B, Schluter D, Bell MA, Kingsley DM. Adaptive evolution of pelvic reduction in sticklebacks by recurrent deletion of a Pitx1 enhancer. Science. 2010;327:302–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1182213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen B, Slack JM. FGF-8 is associated with anteroposterior patterning and limb regeneration in Xenopus. Dev Biol. 1997;192:455–466. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn MJ, Tickle C. Developmental basis of limblessness and axial patterning in snakes. Nature. 1999;399:474–479. doi: 10.1038/20944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper KL, Hu JK-H, Berge ten D, Fernandez-Teran M, Ros MA, Tabin CJ. Initiation of proximal-distal patterning in the vertebrate limb by signals and growth. Science. 2011;332:1083–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1199499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper KL, Oh S, Sung Y, Dasari RR, Kirschner MW, Tabin CJ. Multiple phases of chondrocyte enlargement underlie differences in skeletal proportions. Nature. 2013;495:375–378. doi: 10.1038/nature11940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper KL, Sears KE, Uygur A, Maier J, Baczkowski K-S, Brosnahan M, Antczak D, Skidmore JA, Tabin CJ. Patterning and post-patterning modes of evolutionary digit loss in mammals. Nature. 2014;511:41–45. doi: 10.1038/nature13496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cretekos CJ, Wang Y, Green ED, Martin JF, Rasweiler JJ, Behringer RR. Regulatory divergence modifies limb length between mammals. Genes Dev. 2008;22:141–151. doi: 10.1101/gad.1620408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bakker MAG, Fowler DA, Oude den K, Dondorp EM, Navas MCG, Horbanczuk JO, Sire J-Y, Szczerbińska D, Richardson MK. Digit loss in archosaur evolution and the interplay between selection and constraints. Nature. 2013;500:445–448. doi: 10.1038/nature12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doroba CK, Sears KE. The divergent development of the apical ectodermal ridge in the marsupial Monodelphis domestica. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2010;293:1325–1332. doi: 10.1002/ar.21183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling A, Doroba C, Maier JA, Cohen L, VandeBerg J, Sears KE. Cellular and molecular drivers of differential organ growth: insights from the limbs of Monodelphis domestica. Dev Genes Evol. 2016;226:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s00427-016-0549-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley AT, Ros MA, Tabin CJ. A re-examination of proximodistal patterning during vertebrate limb development. Nature. 2002;418:539–544. doi: 10.1038/nature00945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinson RP, del Pino EM. Developmental diversity of amphibians. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2012;1:345–369. doi: 10.1002/wdev.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T, Yokoyama H, Tamura K, Ide H. Shh expression in developing and regenerating limb buds of Xenopus laevis. Dev Dyn. 1997;209:227–232. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199706)209:2<227::AID-AJA8>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröbisch NB, Bickelmann C, Olori JC, Witzmann F. Deep-time evolution of regeneration and preaxial polarity in tetrapod limb development. Nature. 2015;527:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature15397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröbisch NB, Shubin NH. Salamander limb development: integrating genes, morphology, and fossils. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:1087–1099. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke AR, Shubin NH. Cis-regulatory programs in the development and evolution of vertebrate paired appendages. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros J, Tabin CJ. Vertebrate limb bud formation is initiated by localized epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Science. 2014;343:1253–1256. doi: 10.1126/science.1248228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JB, Kerney R, Hanken J, Tabin CJ. Molecular anatomy of the developing limb in the coquí frog, Eleutherodactylus coqui. Evol Dev. 2011;13:415–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2011.00500.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanken J, Carl TF, Richardson MK, Olsson L, Schlosser G, Osabutey CK, Klymkowsky MW. Limb development in a “nonmodel” vertebrate, the direct-developing frog Eleutherodactylus coqui. J. Exp. Zool. 2001;291:375–388. doi: 10.1002/jez.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe BD, Scherz PJ, Nissim S, Tian H, McMahon AP, Tabin CJ. Evidence for an expansion-based temporal Shh gradient in specifying vertebrate digit identities. Cell. 2004;118:517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harshman J, Braun EL, Braun MJ, Huddleston CJ, Bowie RCK, Chojnowski JL, Hackett SJ, Han K-L, Kimball RT, Marks BD, Miglia KJ, Moore WS, Reddy S, Sheldon FH, Steadman DW, Steppan SJ, Witt CC, Yuri T. Phylogenomic evidence for multiple losses of flight in ratite birds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13462–13467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803242105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infante CR, Mihala AG, Park S, Wang JS, Johnson KK, Lauderdale JD, Menke DB. Shared Enhancer Activity in the Limbs and Phallus and Functional Divergence of a Limb-Genital cis-Regulatory Element in Snakes. Dev Cell. 2015;35:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JR JS, Fallon JH. Major… - Google Scholar. 1966. SAUNDERS JR: Cell death in morphogenesis. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan SR, Beck CW. Xenopus Limb bud morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2016;245:233–243. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyte AL, Smith KK. Developmental origins of precocial forelimbs in marsupial neonates. Development. 2010;137:4283–4294. doi: 10.1242/dev.049445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvon EZ, Kamneva OK, Melo US, Barozzi I, Osterwalder M, Mannion BJ, Tissières V, Pickle CS, Plajzer-Frick I, Lee EA, Kato M, Garvin TH, Akiyama JA, Afzal V, López-Ríos J, Rubin EM, Dickel DE, Pennacchio LA, Visel A. Progressive Loss of Function in a Limb Enhancer during Snake Evolution. Cell. 2016;167:633–642. e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufer E, Nelson CE, Johnson RL, Morgan BA, Tabin C. Sonic hedgehog and Fgf-4 act through a signaling cascade and feedback loop to integrate growth and patterning of the developing limb bud. Cell. 1994;79:993–1003. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal F, Cohn MJ. Loss and Re-emergence of Legs in Snakes by Modular Evolution of Sonic hedgehog and HOXD Enhancers. Curr Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettice LA, Heaney SJH, Purdie LA, Li L, de Beer P, Oostra BA, Goode D, Elgar G, Hill RE, de Graaff E. A long-range Shh enhancer regulates expression in the developing limb and fin and is associated with preaxial polydactyly. Human Molecular Genetics. 2003;12:1725–1735. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandoski M, Sun X, Martin GR. Fgf8 signalling from the AER is essential for normal limb development. Nat Genet. 2000;26:460–463. doi: 10.1038/82609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Ríos J, Duchesne A, Speziale D, Andrey G, Peterson KA, Germann P, Unal E, Liu J, Floriot S, Barbey S, Gallard Y, Müller-Gerbl M, Courtney AD, Klopp C, Rodriguez S, Ivanek R, Beisel C, Wicking C, Iber D, Robert B, McMahon AP, Duboule D, Zeller R. Attenuated sensing of SHH by Ptch1 underlies evolution of bovine limbs. Nature. 2014;511:46–51. doi: 10.1038/nature13289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas SA, Suzuki T, Fallon JF. Identification of spontaneous mutations within the long-range limb-specific Sonic hedgehog enhancer (ZRS) that alter Sonic hedgehog expression in the chicken limb mutants oligozeugodactyly and silkie breed. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:1212–1222. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani FV, Ahn CP, Martin GR. Genetic evidence that FGFs have an instructive role in limb proximal-distal patterning. Nature. 2008;453:401–405. doi: 10.1038/nature06876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JF, Bradley A, Olson EN. The paired-like homeo box gene MHox is required for early events of skeletogenesis in multiple lineages. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1237–1249. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith RW, Janečka JE, Gatesy J, Ryder OA, Fisher CA, Teeling EC, Goodbla A, Eizirik E, Simão TLL, Stadler T, Rabosky DL, Honeycutt RL, Flynn JJ, Ingram CM, Steiner C, Williams TL, Robinson TJ, Burk-Herrick A, Westerman M, Ayoub NA, Springer MS, Murphy WJ. Impacts of the Cretaceous Terrestrial Revolution and KPg extinction on mammal diversification. Science. 2011;334:521–524. doi: 10.1126/science.1211028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino R, Rodriguez-Leon J, Macias D, Gañan Y, Economides AN, Hurle JM. The BMP antagonist Gremlin regulates outgrowth, chondrogenesis and programmed cell death in the developing limb. Development. 1999;126:5515–5522. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minguillon C, Nishimoto S, Wood S, Vendrell E, Gibson-Brown JJ, Logan MPO. Hox genes regulate the onset of Tbx5 expression in the forelimb. Development. 2012;139:3180–3188. doi: 10.1242/dev.084814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TH. Regeneration of the leg of Amphiuma means. Biol. Bull. 1903 [Google Scholar]

- Nagai H, Mak S-S, Weng W, Nakaya Y, Ladher R, Sheng G. Embryonic development of the emu, Dromaius novaehollandiae. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:162–175. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CE, Morgan BA, Burke AC, Laufer E, DiMambro E, Murtaugh LC, Gonzales E, Tessarollo L, Parada LF, Tabin C. Analysis of Hox gene expression in the chick limb bud. Development. 1996;122:1449–1466. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto S, Minguillon C, Wood S, Logan MPO. A combination of activation and repression by a colinear Hox code controls forelimb-restricted expression of Tbx5 and reveals Hox protein specificity. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswander L, Jeffrey S, Martin GR, Tickle C. A positive feedback loop coordinates growth and patterning in the vertebrate limb. Nature. 1994;371:609–612. doi: 10.1038/371609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohuchi H, Nakagawa T, Yamamoto A, Araga A, Ohata T, Ishimaru Y, Yoshioka H, Kuwana T, Nohno T, Yamasaki M, Itoh N, Noji S. The mesenchymal factor, FGF10, initiates and maintains the outgrowth of the chick limb bud through interaction with FGF8, an apical ectodermal factor. Development. 1997;124:2235–2244. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.11.2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rallis C, Bruneau BG, Del Buono J, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Nissim S, Tabin CJ, Logan MPO. Tbx5 is required for forelimb bud formation and continued outgrowth. Development. 2003;130:2741–2751. doi: 10.1242/dev.00473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MK, Carl TF, Hanken J, Elinson RP, Cope C, Bagley P. Limb development and evolution: a frog embryo with no apical ectodermal ridge (AER) J. Anat. 1998;192(Pt 3):379–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1998.19230379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MK, Oelschläger HHA. Time, pattern, and heterochrony: a study of hyperphalangy in the dolphin embryo flipper. Evol Dev. 2002;4:435–444. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2002.02032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle RD, Johnson RL, Laufer E, Tabin C. Sonic hedgehog mediates the polarizing activity of the ZPA. Cell. 1993;75:1401–1416. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90626-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelants K, Gower DJ, Wilkinson M, Loader SP, Biju SD, Guillaume K, Moriau L, Bossuyt F. Global patterns of diversification in the history of modern amphibians. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:887–892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608378104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolian C. Developmental basis of limb length in rodents: evidence for multiple divisions of labor in mechanisms of endochondral bone growth. Evol Dev. 2008;10:15–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ros MA, Dahn RD, Fernandez-Teran M, Rashka K, Caruccio NC, Hasso SM, Bitgood JJ, Lancman JJ, Fallon JF. The chick oligozeugodactyly (ozd) mutant lacks sonic hedgehog function in the limb. Development. 2003;130:527–537. doi: 10.1242/dev.00245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselló-Díez A, Ros MA, Torres M. Diffusible signals, not autonomous mechanisms, determine the main proximodistal limb subdivision. Science. 2011;332:1086–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.1199489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagai T, Hosoya M, Mizushina Y, Tamura M, Shiroishi T. Elimination of a long-range cis-regulatory module causes complete loss of limb-specific Shh expression and truncation of the mouse limb. Development. 2005;132:797–803. doi: 10.1242/dev.01613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiz-Lopez P, Chinnaiya K, Campa VM, Delgado I, Ros MA, Towers M. An intrinsic timer specifies distal structures of the vertebrate limb. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8108. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JW. How serendipity shaped a life; an interview with John W. Saunders, Jr. by John F. Fallon. The International journal of developmental biology. 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JW. Apical ectodermal ridge in retrospect. J. Exp. Zool. 1998;282:669–676. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-010x(19981215)282:6<669::aid-jez3>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JW, Gasseling MT. Cellular death in morphogenesis of the avian wing. Dev Biol. 1962;5:147–178. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(62)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherz PJ, Harfe BD, McMahon AP, Tabin CJ. The limb bud Shh-Fgf feedback loop is terminated by expansion of former ZPA cells. Science. 2004;305:396–399. doi: 10.1126/science.1096966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherz PJ, McGlinn E, Nissim S, Tabin CJ. Extended exposure to Sonic hedgehog is required for patterning the posterior digits of the vertebrate limb. Dev Biol. 2007;308:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears KE. Differences in the timing of prechondrogenic limb development in mammals: the marsupial-placental dichotomy resolved. Evolution. 2009;63:2193–2200. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears KE, Behringer RR, Rasweiler JJ, Niswander LA. Development of bat flight: morphologic and molecular evolution of bat wing digits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6581–6586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509716103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears KE, Patel A, Hübler M, Cao X, Vandeberg JL, Zhong S. Disparate Igf1 expression and growth in the fore- and hind limbs of a marsupial mammal (Monodelphis domestica) J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2012;318:279–293. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.22444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MD. Developmental morphology of limb reduction in Hemiergis (Squamata: Scincidae): chondrogenesis, osteogenesis, and heterochrony. J Morphol. 2002;254:211–231. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MD, Hanken J, Rosenthal N. Developmental basis of evolutionary digit loss in the Australian lizard Hemiergis. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2003;297:48–56. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MD, Marks ME, Peichel CL, Blackman BK, Nereng KS, Jónsson B, Schluter D, Kingsley DM. Genetic and developmental basis of evolutionary pelvic reduction in threespine sticklebacks. Nature. 2004;428:717–723. doi: 10.1038/nature02415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shubin NH, Alberch P. Evolutionary Biology. US, Boston, MA: Springer; 1986. A Morphogenetic Approach to the Origin and Basic Organization of the Tetrapod Limb; pp. 319–387. [Google Scholar]

- Summerbell D, Lewis JH, Wolpert L. Positional information in chick limb morphogenesis. Nature. 1973;244:492–496. doi: 10.1038/244492a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M. Fins into limbs: Autopod acquisition and anterior elements reduction by modifying gene networks involving 5'Hox, Gli3, and Shh. Dev Biol. 2016;413:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarchini B, Duboule D. Control of Hoxd genes' collinearity during early limb development. Dev Cell. 2006;10:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thewissen JGM, Cohn MJ, Stevens LS, Bajpai S, Heyning J, Horton WE. Developmental basis for hind-limb loss in dolphins and origin of the cetacean bodyplan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8414–8418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602920103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheyden JM, Sun X. An Fgf/Gremlin inhibitory feedback loop triggers termination of limb bud outgrowth. Nature. 2008;454:638–641. doi: 10.1038/nature07085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GP, KHAN PA, BLANCO MJ, MISOF B, LIVERSAGE RA. Evolution of Hoxa-11Expression in Amphibians: Is the Urodele Autopodium an Innovation? Am Zool. 1999;39:686–694. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherbee SD, Behringer RR, Rasweiler JJ, Niswander LA. Interdigital webbing retention in bat wings illustrates genetic changes underlying amniote limb diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15103–15107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604934103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welscher, te P, Fernandez-Teran M, Ros MA, Zeller R. Mutual genetic antagonism involving GLI3 and dHAND prepatterns the vertebrate limb bud mesenchyme prior to SHH signaling. Genes Dev. 2002;16:421–426. doi: 10.1101/gad.219202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsman NJ, Farnum CE, Leiferman EM, Fry M, Barreto C. Differential growth by growth plates as a function of multiple parameters of chondrocytic kinetics. J. Orthop. Res. 1996;14:927–936. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100140613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakany J, Kmita M, Duboule D. A dual role for Hox genes in limb anterior-posterior asymmetry. Science. 2004;304:1669–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.1096049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Wake DB. Higher-level salamander relationships and divergence dates inferred from complete mitochondrial genomes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2009;53:492–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Nakamura E, Nguyen M-T, Bao X, Akiyama H, Mackem S. Uncoupling Sonic hedgehog control of pattern and expansion of the developing limb bud. Dev Cell. 2008;14:624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, Niswander L. Requirement for BMP signaling in interdigital apoptosis and scale formation. Science. 1996;272:738–741. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga A, Haramis AP, McMahon AP, Zeller R. Signal relay by BMP antagonism controls the SHH/FGF4 feedback loop in vertebrate limb buds. Nature. 1999;401:598–602. doi: 10.1038/44157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]