Abstract

Pseudomonas putida KT2440 is a model bacteria used commonly for medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates (mcl-PHAs) production using various substrates. However, despite many studies conducted on P. putida KT2440 strain, the molecular mechanisms of leading to mcl-PHAs synthesis in reaction to environmental stimuli are still not clear. The rearrangement of the metabolism in response to environmental stress could be controlled by stringent response that modulates the transcription of many genes in order to promote survival under nutritional deprivation conditions. Therefore, in this work we investigated the relation between mcl-PHAs synthesis and stringent response. For this study, a relA/spoT mutant of P. putida KT2440, unable to induce the stringent response, was used. Additionally, the transcriptome of this mutant was analyzed using RNA-seq in order to examine rearrangements of the metabolism during cultivation. The results show that the relA/spoT mutant of P. putida KT2440 is able to accumulate mcl-PHAs in both optimal and nitrogen limiting conditions. Nitrogen starvation did not change the efficiency of mcl-PHAs synthesis in this mutant. The transition from exponential growth to stationary phase caused significant upregulation of genes involved in transport system and nitrogen metabolism. Transcriptional regulators, including rpoS, rpoN and rpoD, did not show changes in transcript abundance when entering the stationary phase, suggesting their limited role in mcl-PHAs accumulation during stationary phase.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13568-017-0396-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Global regulation, Pseudomonas putida KT2440, Polyhydroxyalkanoates, Stringent response, Transcriptomics

Introduction

To survive in the harsh conditions, microorganisms need to be able to adapt to a competitive and changing environment. In response to changes in environmental conditions, the physiological status of microorganisms can change due to the actions of transcriptional regulatory systems. Generally, transcription regulation occurs at two different levels. Firstly, regulation can drive the expression of relevant pathway genes in reaction to a specific inducer. Secondly, global regulatory systems can adjust the expression of the pathway gene cluster in response to the general physiological status of the microorganism. The main regulators at this higher level are alternative RNA polymerase sigma subunits (Díaz and Prieto 2000).

One of the survival strategies, that microorganisms living in stressful environments have developed, is synthesis and accumulation of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) in aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Poirier et al. 1995). PHAs play an important role in central metabolism because they serve as a reservoir of carbon and reducing equivalents. The most common PHA is poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB), composed of monomers containing four carbon atoms, whereas medium-chain-length PHAs, containing from 6 to 14 carbon atoms in single monomer, are less abundant. The accumulation of PHAs may increase the survival capabilities of these bacteria in extreme environments or when nutrient availability is poor (Ayub et al. 2009). Because of the complexity of PHAs metabolism knowledge on the re-configuration of the bacteria whole metabolism under the conditions that lead to mcl-PHAs synthesis is still not clear. In Pseudomonas species the pha cluster is very well conserved and is organized into two operons phaC1ZC2D and phaFI. Two polymerases (PhaC1 and PhaC2), a depolymerase (PhaZ), a transcriptional activator (PhaD) and proteins involved in granule formations (PhaF and PhaI) are essential to accumulate and synthesize these biopolyesters. It has been suggested that PhaG encodes transacylase, being not co-localized with the pha gene cluster, is also involved in mcl-PHAs synthesis from non-related carbon sources (Hoffmann and Rehm 2004). It is known that PHAs are accumulated by pseudomonads mainly in response to unbalanced growth conditions such as a lack of nitrogen, which links PHAs accumulation to the stringent response (López et al. 2015).

The stringent response modifies the physiology of the bacterium to such an extent that it can survive difficult environmental circumstances during its lifecycle. This response is mediated by the alarmons-unusual nucleotides, guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp) and guanosine pentaphosphate (pppGpp), often referred collectively to (p)ppGpp, which primarily affects the transcriptional program of the bacterial cell (Potrykus and Cashel 2008). In model bacteria, Escherichia coli and many beta- and gammaproteobacteria, including P. putida, two enzymes modulate the levels of ppGpp (Mittenhuber 2001; Atkinson et al. 2011): the ppGpp synthetase RelA, responsive to amino acid starvation and ppGpp synthetase/hydrolase SpoT, producing (p)ppGpp under other nutrients limitations and stresses (Potrykus and Cashel 2008). Stringent response contributes to stress adaptation, antibiotic tolerance, expression of virulence traits and acquisition of persistent phenotypes in pathogenic bacteria. The regulation of the mode of action of the RelA/SpoT enzymes has been extensively studied, but the regulatory mechanisms that manage transcription of their genes are still not fully understood (Brown et al. 2014).

Recently, Brigham and co-workers (2012) revealed that the polyhydroxybutyrate production cycle in Ralstonia eutropha H16 is regulated by the stringent response. The results indicated that R. eutropha mutant unable to produce ppGpp did not accumulate PHB unless the stringent response was chemically induced. Previously, Ruiz et al. (2001) had shown that alarmones accumulation and PHB degradation are associated in Pseudomonas oleovorans: as PHB were degraded, ATP and ppGpp levels increased. They suggested that the stringent response influenced PHB utilization by activation of RpoS synthesis. Because of these previous studies and the importance of the stringent response in reprogramming bacterial transcription, we hypothesized that P. putida deficient in the stringent response may be impaired in mcl-PHAs synthesis.

Thus, to examine the role of the stringent response in mcl-PHAs synthesis, P. putida KT2440, a model organism for mcl-PHAs production, was used. A set of experiments were performed to determine the possibility of mcl-PHAs accumulation by P. putida KT2440 mutant deficient in stringent response and to investigate the molecular background of this process. Firstly, in shaking flasks experiments, the mcl-PHAs accumulation bioprocess stimulated by nitrogen starvation in P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant and wild type of P. putida KT2440 was compared. Additionally, P. putida KT2440 rpoN mutant was used in this comparison to examine the role of RpoN in mcl-PHAs synthesis under nitrogen deprivation conditions. Secondly, the cultivation of P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant in a bioreactor was conducted to monitor cell growth and biopolymers accumulation over time. Moreover, the transcriptome of P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant cultivated in the bioreactor was analyzed in order to show rearrangements of the metabolism during fermentation towards mcl-PHAs synthesis.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain and growth conditions

Cells of P. putida KT2440 (ATCC® 47054™), P. putida KT2440 rpoN mutant (Köhler et al. 1989), and P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT (Sze et al. 2002) mutant were taken from a deep-frozen stock and grown overnight in Luria–Bertani broth (1% w/v tryptone, 0.5% w/v yeast extract, 1% NaCl) with shaking at 30 °C with 200 rpm for 24 h before inoculation. All studied strains were cultivated under nitrogen-limiting and non-limiting conditions. For all cultivations, the nitrogen-limited medium contained the following components per liter: 2 g Na2HPO4⋅12H2O, 14.9 g KCl, 46.72 g NaCl, 14.5 g Tris, 2.05 g MgCl2, 3.53 g Na2SO4, 1 g (NH4)2 SO4, 1 g MgSO4⋅7H2O, and 2.5 mL of trace element solution. In the non-limited experiments, the level of (NH4)2 SO4 was adjusted to 10 g/L. Each liter of trace element solution contained per liter: 20 g FeCl3⋅6H2O, 10 g CaCl2⋅H2O, 0,03 g CuSO4⋅5H2O, 0,05 g MnCl2⋅4H2O, 0,1 g ZnSO4⋅7H2O dissolved in 0.5 N HCl. All cultures were supplemented with oleic acid (10 mL/L) as the only carbon source in the production media. The 250-mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL of a mineral medium were incubated for 48 h at 30 °C in a rotary shaker at 200 rpm. The shaking flasks cultivations were performed in six replicates for each condition and for each strain.

The fermentation study of P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant was carried out in a 5 L working volume in a bioreactor (BioFlo 110, New Brunswick Scientific) at 30 °C with an aeration rate of 4 L/min. Parameters like dissolved oxygen, pH value, biomass, mcl-PHA, nitrogen and carbon concentrations were controlled during the experiments.

pH-value was maintained at seven through the modulated addition of concentrated 1 N NaOH and 1 N HCl. The dissolved oxygen was monitored during the whole cycle with O2 electrode (InPro 6800, Mettler Toledo GmbH, Switzerland). Total fermentation time was 48 h.

Analytical methods

The samples from shake flasks experiment were taken after 48 h of cultivation in order to measure cell dry weight and PHA concentration. The cell density of the cultures in the bioreactor was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm (OD600) using a spectrophotometer. During the cultivation in the bioreactor the samples were taken at 8, 17, 24, 32, 41 and 48 h for measurements of cell dry weight, mcl-PHAs accumulation, ammonium/carbon concentration and for determination of monomers composition and their concentrations. To measure cell dry weight (CDW), the cells in 100 mL culture broth were harvested by centrifugation at 11.200×g for 10 min, washed twice with hexane to remove unused oleic acid and once with distilled water. The collected cells were then weighed after lyophilization. The lyophilization process was performed by Lyovac GT2 System (SRK Systemtechnik GmbH) for 24 h. Ammonium and total organic carbon (TOC) concentration was measured spectrophotometrically using the Hach Lange DR 2800 spectrophotometer (Hach Lange, Düsseldorf DE) and the LCK303 kit for ammonium and LCK380 kit for TOC according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Mcl-PHAs were extracted from lyophilized cells using the chloroform/methanol procedure for quantitative and qualitative analysis of biopolymers. The monomeric composition of the purified mcl-PHAs was determined using a methanolysis protocol as described previously (Mozejko and Ciesielski 2014). The concentrations of methyl esters were estimated by a gas chromatography (GC) equipped with a capillary column Varian VF-5 ms with a film thickness of 0.25 μm (Varian, Lake Forest, USA). Pure standards of methyl 3-hydroxy-hexanoate, -octanoate, -nonanoate, -decanoate, -undecanoate, -dodecanoate, -tetradecanoate, -hexadecanoate were used to generate calibration curves for the methanolysis assay. All samples were analyzed in triplicates.

Cell dry weight and PHA concentration analysis in biomass from shake flasks and fermentor were performed in this same way. Student t test was used to find statistically significant differences between biomass and PHA concentration.

RNA isolation

One aliquot of 20 mL from each of cultures were collected and centrifuged at 4000×g to pellet the cells and then transferred to a Falcon tube containing RNAlater solution (Sigma). Total RNA extraction was performed using a commercial RNA extraction kit (A&A Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Isolated RNA samples were treated with On-Column DNase I Digest Set (Sigma) to remove traces of DNA. Each time the absence of contaminating DNA was proven by PCR reaction. The RNA quantity, quality was checked using capillary electrophoresis (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, California, USA). The RNA integrity number (RIN) of every RNA sample used for sequencing was more than 8.0.

Reverse transcription PCR analysis

Reverse transcription was performed using a SuperScript Vilo™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The cDNA reaction for each sample contained 1 μg of total RNA. Samples, without reverse transcriptase (RT) were used as a negative control. The synthesized first strand cDNA was suspended in sterile water and stored at −20 °C. Real-time PCR reaction was performed using SYBR Green technology in an ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA) in MicroAmpTM optical 96-well reaction plates (Applied Biosystems, USA). The primer pairs used for real-time amplification are given in Table 1. The reactions were run using the thermal cycling parameters as follows: 95 °C for 3 min, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 1 min. After performing a run, a final standard melting curve stage was included. In each run, negative controls (no cDNA) for each primer set were included. For quantification of the fluorescence values, a calibration curve was made using dilution series from 5 × 10−7 to 5 ng of P. putida KT2440 genomic DNA sample. Normalized expression levels of the examined transcripts were estimated relative to the 16S rRNA gene, as its expression is known to remain relatively constant throughout growth phase of P. putida. Then, the concentration of P. putida KT2440 DNA was converted to a genome equivalent for calculation of copy numbers in the real-time PCR assays (Cottyn et al. 2011). For the convenience, the genome size of P. putida KT2440 (6.18 × 106 bp) available at NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) was used to estimate the mean mass of the P. putida KT2440 genome accordingly to the equation:

where n is the genome size in base pairs, mw is the average molecular weight per base pairs (660 g/mol), and AN is the Avogadro constant (6.023 × 1023 molecules/mol).

Table 1.

Details of the PCR primers used in this study

| Name | Amplicon | Sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GlC1 179R |

phaC1 | 5′-AAGGTCAACGCCCTGCTGGGT-3′ 5′-GGTGTTGTCGTTGTTCCAGTAGAGGATGTC-3′ |

(Ciesielski et al. 2010) (Solaiman et al. 2000) |

| ZRT5 ZRT3 |

phaZ | 5′-GAAGTCATCGCCTTTGATGTGCC-3′ 5′-ATCATCCACAGCACCTTGGGCTTG-3′ |

This study This study |

| C2RT5 C2RT3 |

phaC2 | 5′-GCGGCGTGGCTCACCTG-3′ 5′-GAAGCTGTTGGTCGCGCTG-3′ |

This study This study |

| D-RTf D-RTr |

phaD | 5′-CATCAGCCCAGGCAACCTGTAC-3′ 5′-GCGCTCGACGATCAAGTGCAG-3′ |

This study This study |

| F-RTf F-RTr |

phaF | 5′-GTCATGTTTAGACGGAATACCCAG-3′ 5′-GCGGCCAACCACCAGCTTG-3′ |

This study This study |

| I-RTf I-RTr |

phaI | 5′-GCACCGGTCAGCTTCTCGATC-3′ 5′-GGAGCGAACTTGAAGAAGCC-3′ |

This study This study |

| phaG2F phaG2R |

phaG | 5′-TTCAAACGCTTCAACTACCGCC-3′ 5′-CGGTCTTGTTCTCCATGTCCAG-3′ |

This study This study |

| 341F 515R |

16S rRNA | 5′-CCT ACG GGA GGC AGC AG-3′ 5′-AAT CCG CGG CTG GCA-3′ |

(López-Gutiérrez et al. 2004) |

Library construction, illumina sequencing and data analysis

RNAseq template libraries were constructed with 1 μg of the enriched mRNA samples using Truseq RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, California, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Deep sequencing was performed by Illumina HiSeq 2500 according to the manufacturer’s description with a read length of 1 × 50 nucleotides. Sequence reads were pre-processed to trim low-quality reads and filter reads shorter than 20 bp using FASTX Tool Kit. Genome sequences and annotation data of P. putida KT2440 were downloaded from NCBI (downloaded on 10 November, 2016). Reads that mapped to non-coding RNA sequences and reads that did not map to unique positions were excluded from further analysis. Remaining reads were mapped to P. putida KT2440 genome using Bowtie with the default parameters. The reads per gene values of all genes were calculated from the SAM output files. Testing for differential expression was performed with DESeq and R software package that uses a statistical model based on the negative bionomial distribution (Anders and Huber 2010). Statistical analysis was performed and genes with a false discovery rate (FDR) p value correction <0.05 were determined as differentially regulated genes. The raw RNAseq data were deposited to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with BioProject accession PRJNA374570.

Results

PHAs synthesis in shake flask cultures experiment

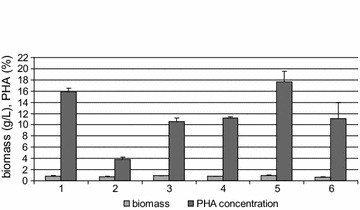

In order to examine the relationship between the stringent response and mcl-PHAs synthesis, P. putida KT2440 and its mutant with non-functional relA/spoT genes were cultivated in shaking flasks. Additionally, an RpoN-deficient mutant of P. putida KT2440 was used to reveal the role of RpoN in the regulatory network that controls mcl-PHAs synthesis in culture supplemented with oleic acid. All cultivations were carried out in six replicates under optimal growth conditions and under nitrogen limitation. After 48 h of growth, final cell dry weight (CDW) ranged from 0.63 to 0.98 g/L (Fig. 1). Under nitrogen limitation, the wild-form and rpoN mutant accumulated the largest amounts of mcl-PHAs (15.9 and 17.7% mcl-PHAs of CDW, respectively). Under optimal conditions, these two strains accumulated significantly less mcl-PHAs (3.8 and 11.1% mcl-PHAs of CDW, respectively; p < 0.05). The relA/spoT mutant synthesized similar amounts of mcl-PHAs in both optimal and nitrogen limiting conditions (10.6 and 11.2% mcl-PHAs of CDW, respectively). In both conditions the PHA concentration in relA/spoT mutant cells was significantly lower than in wild-form cells (p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Mcl-PHAs content and biomass concentration of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 wild-type (1 and 2), P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant (3 and 4) and P. putida KT2440 rpoN mutant (5 and 6). The shake flasks cultivation was performed under nitrogen limitation (1, 3, and 5) and optimal (2, 4, and 6) conditions. Each data represents the mean ± standard deviation

PHAs synthesis during bioreactor cultivation

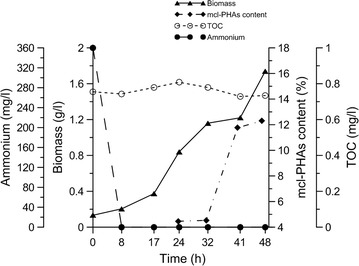

To characterize the process of mcl-PHAs synthesis by P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant, fed-batch culture was carried out for 48 h in a 5-L bioreactor. The first evidence of mcl-PHAs synthesis was noted at 24 h, but up to 32 h of cultivation, mcl-PHAs concentration remained below 4.5% CDW. After that, mcl-PHAs concentration started to increase rapidly, reaching 12.3% CDW at 48 h, when cell dry weight (1.74 g/L) also reached its maximum value. During fermentation, total nitrogen and phosphorus concentration decreased with time, whereas total carbon concentration was similar throughout cultivation (0.8 g/L). As can be seen in Fig. 2, ammonium was completely consumed during the first 8 h of cultivation

Fig. 2.

Growth and mcl-PHAs accumulation during 48 h cultivation of P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant in bioreactor

The major repeat units of the mcl-PHAs produced by P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant on oleic acid were 3-hydroxyoctanoate and 3-hydroxyhexanoate, whereas 3-hydroxyhexanoate and 3-hydroxydodecanoate were found in smaller amounts (Table 2). The composition of the PHAs synthesized by this mutant was similar to composition of mcl-PHAs produced by other Pseudomonas species cultivated on fatty acids (Ciesielski and Mozejko 2015).

Table 2.

Monomeric composition of mcl-PHAs synthesized by Pseudomonas putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant

| Culture time (h) | mcl-PHAs composition (mol%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3HB | 3HHx | 3HO | 3HN | 3HD | 3HUD | 3HDD | 3HTD | 3HHxD | |

| 24 | n.d. | n.d. | 38.5 ± 5.8 | n.d. | 41.4 ± 5.4 | n.d. | 20.1 ± 4.1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 32 | n.d. | 6.0 ± 1.1 | 50.0 ± 4.7 | n.d. | 31.6 ± 5.1 | n.d. | 12.4 ± 2.5 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 41 | n.d. | n.d. | 45.9 ± 5.5 | n.d. | 39.4 ± 2.7 | n.d. | 14.7 ± 1.8 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 48 | n.d. | 6.5 ± 2.0 | 47.7 ± 11.7 | n.d. | 32.3 ± 5.9 | n.d. | 13.5 ± 3.5 | n.d. | n.d. |

3HB 3-hydroxybutyrate, 3HHx 3-hydroxyhexanoate, 3HO 3-hydroxyoctanoate, 3HN 3-hydroxynonanoate, 3HD 3-hydroxydecanoate, 3HUD 3-hydroxyundecanoate, 3HDD 3-hydroxydodecanoate, 3HTD 3-hydroxytetradecanoate, 3HHxD 3-hydroxyhexadecanoate, n.d. not detected

Analysis of mcl-PHAs related genes using reverse transcription real-time PCR

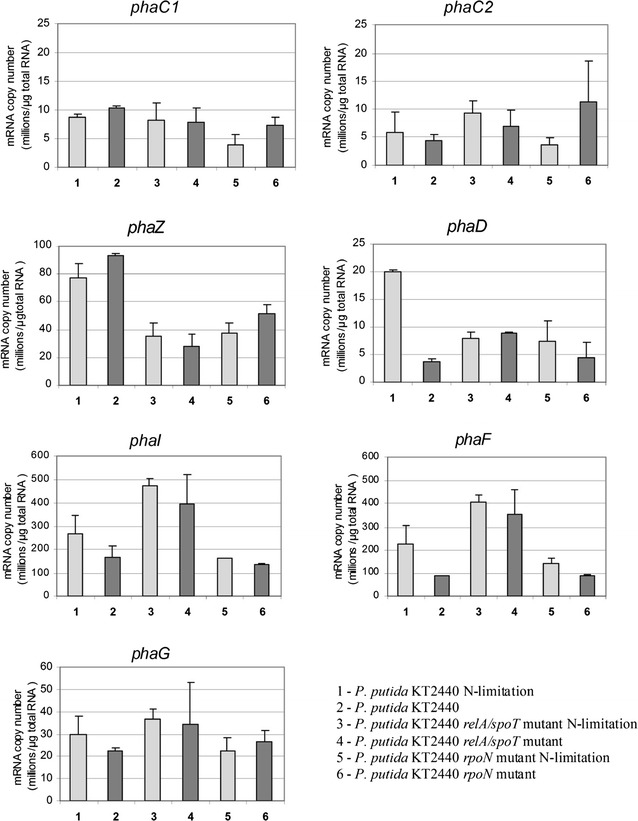

The transcriptional expression levels of phaC1, phaZ, phaC2, phaD, phaI, phaF, and phaG genes were examined. The transcription of all these genes was investigated in flask cultures at 48 h of cultivation. The results in Fig. 3 show that the mRNA copy numbers varied between analyzed strains and conditions. Nitrogen limiting conditions did not increase transcription of phaC1, phaC2, and phaZ genes in any of the analyzed strains. Under both conditions, expression of the phaZ gene was significantly higher in the wild-type than in the mutant. Under nitrogen limiting conditions, the number of phaD gene transcripts was significantly higher in the wild-form than in the mutant (20.0 vs. 3.6 million copies). Although phaD is considered a possible regulator of the PC1 promoter, these results did not show that the changes in phaD had any effect on phaC1, phaC2, and phaZ expression.

Fig. 3.

The result of quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR analysis of phaC1, phaZ, phaC2, phaD, phaI, phaF, and phaG genes. Samples were taken at 48 h of cultivation. Each data represents the mean ± standard deviation

In all strains, phaI and phaF expression was much higher than expression of other genes directly involved in PHAs synthesis, and the transcript numbers of phaI and phaF were higher in nitrogen limiting conditions. Similar profile was observed for phaG, although its expression level was rather comparable to phaZ gene. Whereas the expression of phaI, phaF, and phaG in the relA/spoT mutant was significantly higher than their expression in the other strains, the expression of phaC1, phaC2, phaZ, and phaD did not differ significantly between strains.

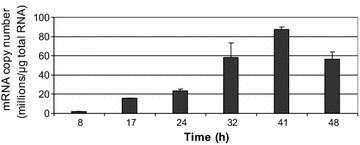

Additionally, the expression of phaG was investigated at six time-points during relA/spoT mutant cultivation in the bioreactor (Fig. 4). The phaG transcript number increased from the beginning of cultivation until 41 h and then decreased. The changes in phaG gene transcription between the exponential growth phase and the stationary phase that were obtained using real-time PCR and RNA-seq were the same.

Fig. 4.

The result of quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR analysis of phaG gene. Samples were taken during cultivation of P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant in bioreactor

Transcriptional analysis using RNA-seq

To investigate how P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT responds at the molecular level to a decrease in nutrient availability and metabolically adapts to deteriorating conditions, samples were withdrawn for RNA-seq at the end of the exponential phase (24 h) and in the middle of the stationary phase (41 h). The sequence reads matched to 5517 coding genes in the P. putida KT2440 genome (Nelson et al. 2002), indicating that the sequencing was deep enough to cover almost all kinds of transcripts in the cells. From the sample withdrawn at 24 h, 18,290,865 sequences of cDNA from mRNA transcripts were obtained; from the sample taken at 41 h, 10,847,701 sequences were obtained.

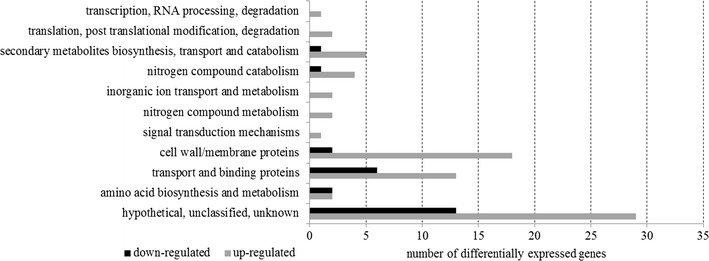

The RNA-seq analysis revealed that, 104 genes were singnificantly differentially expressed between 24 and 41 h of the cultivation. Most of these differentially expressed genes were up-regulated (78 genes), with fold changes ranging from 8.6 to 106.3 (Additional file 1: Table S1). These genes were classified into categories according to the UniProt annotation pipeline (Fig. 5). With regard to the genes directly involved in mcl-PHAs synthesis or degradation, their expression did not differ significantly between the exponential and the stationary phase.

Fig. 5.

Gene ontology analysis of the significantly differentially expressed genes between exponential growth and stationary phase of P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant cultivation

With the exception of genes coding for proteins involved in amino acid biosynthesis and metabolism, many more genes were upregulated during the stationary phase than were downregulated. Almost half of all the genes showing significant differences in transcription (42 genes) were classified as coding for unknown/hypothetical proteins due to a lack of corresponding genes in databases. The next two largest groups of differentially transcribed genes were associated with cell membrane, cell wall proteins and transport and binding protein. Although there were some downregulated genes in these two groups, as in the group of unknown/hypothetical proteins, in all three groups the number of downregulated genes was less than the number of those that were upregulated. This pattern was also observed in the genes involved in secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism, and in those responsible for nitrogen compounds catabolism.

More specifically, the genes that were highly upregulated in the stationary phase are mostly involved in the expression of branched-chain amino acid ABC transporters (e.g. urtA, urtC, urtD). Other upregulated genes code for proteins that participate in nitrogen metabolism. Among these genes were the nitrite reductase small (nirD) and large (nirB) units, and the nitrite transporter (nasA). Other upregulated genes code for the urease subunits gamma (ureA) and alpha (ureC) and for urease accessory proteins (ureD, ureE, ureF, ureJ). Moreover, genes that were upregulated in the stationary phase are involved in fatty acid metabolism: long-chain-fatty-acid-CoA-ligase (PP_2709) and short-chain-dehydrogenase (PP_2711). Furthermore, STRING analysis indicated that some of the significantly upregulated genes that code for hypothetical proteins (PP_2708, PP_2710, PP_2711) are most likely also involved in fatty acids metabolism. Genes involved in the β-oxidation cycle (fadA, fadB, fadAx, fadBx) did not show significant changes in their transcription. Most of the downregulated genes belonged to the group of hypothetical proteins, with one exception: transcription of the gene that codes for the amino acid transporter LysE was about 50 times lower in the stationary phase.

Although some genes directly involved in mcl-PHAs synthesis and degradation changed during a shift from exponential growth to stationary phase, these changes were not statistically significant. However, to show even small changes of this genes transcription, the values of RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase per Million) were used to calculate fold-change values (Table 3). Genes coding for phaC1, phaZ, phaC2, phaF, and phaI showed upregulation in the range from 1.3 to 1.8. PhaG gene coding for (R)-3-hydroxydecanoyl-ACP:CoA transacylase showed almost six-fold increase in the stationary phase. Only gene, that showed small downregulation was phaD, its calculated fold-change was only at the level of 1.1.

Table 3.

Differences in pha genes transcription between exponential growth (24 h) and stationary phase (41 h) expressed in RPKM

| Gene | Locus tag | Description | RPKM 24 h | RPKM 41 h | Fold change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| phaC1 | PP_5003 | PHA polymerase | 638.8 | 834.8 | 1.3 | Up |

| phaZ | PP_5004 | PHA depolymerase | 128.6 | 161.2 | 1.3 | UP |

| phaC2 | PP_5005 | PHA polymerase | 164.8 | 183.2 | 1.1 | UP |

| phaD | PP_5006 | Transcriptional regulator | 216.6 | 197.5 | 1.1 | Down |

| phaF | PP_5007 | PHA granule-associated | 6550.2 | 9404.0 | 1.4 | Up |

| phaI | PP_5008 | PHA granule-associated | 3360.2 | 5976.8 | 1.8 | Up |

| phaG | PP_1408 | Acyl-transferase | 538.02 | 3179.0 | 5.9 | Up |

Similarly, genes playing the regulatory functions were also investigated accurately (Table 4). All genes coding for RNA polymerase subunits and sigma factors displayed small downregulation. The transcription of Lrp (leucine-responsive regulatory protein) increased about 1.3 in stationary phase, similarly Anr (anaerobic regulatory protein), that showed 1.2 upregulation. Catabolic repression control protein (Crc) changed slightly in the stationary phase (fold-change = 1.1).

Table 4.

Differences in regulatory genes transcription between exponential growth (24 h) and stationary phase (41 h) expressed in RPKM

| Gene | Locus tag | Description | RPKM 24 h | RPKM 41 h | Fold change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ntrC | PP_5048 | Fis family transcriptional regulator | 62.1 | 547.7 | 8.8 | Up |

| glnK | PP_5234 | Regulatory protein | 8152.0 | 47668.9 | 5.8 | Up |

| lrp | PP_5271 | Leucine-responsive regulatory protein | 396.2 | 499.0 | 1.3 | Up |

| psrA | PP_2144 | Transcriptional repressor, TetR family | 2028.2 | 1349.0 | 1.5 | Down |

| rpoS | PP_1623 | Sigma factor RpoS | 9969.7 | 9452.2 | 1.1 | Down |

| rpoD | PP_0387 | Sigma factor RpoD | 2845.4 | 2825.1 | 1.1 | Down |

| rpoN | PP_0952 | Sigma factor RpoN | 699.2 | 558.1 | 1.3 | Down |

| rpoA | PP_0479 | RNA polymerase subunit alpha | 5534.4 | 4088.8 | 1.4 | Down |

| rpoB | PP_0447 | RNA polymerase subunit beta | 1443.0 | 1112.9 | 1.3 | Down |

| rpoC | PP_0448 | RNA polymerase subunit beta | 1716.1 | 1329.8 | 1.3 | Down |

| crc | PP_5292 | Catabolite repression control protein | 1860.3 | 1655.0 | 1.1 | Down |

| gacS | PP_1650 | Sensor kinase | 68.7 | 97.9 | 1.4 | Up |

| gacA | PP_4099 | DNA-binding response regulator GacA | 1413.5 | 1169.3 | 1.2 | Down |

| Unknown gene | PP_2475 | Transcriptional regulator, TetR family | 1296.3 | 17129.2 | 13.2 | Up |

| Unknown gene | PP_1863 | Transcriptional regulator, LysR family | 154.7 | 307.5 | 1.9 | Up |

Most of the transcriptional regulators showed only small changes in expression between exponential growth and stationary phase (Table 4). The first exception was transcriptional regulator from Fis family (ntrC), the main nitrogen stress factor, that showed almost ninefold upregulation. The second exception was transcriptional regulator from TetR family that was activated in stationary phase (fold change 13.2).

Discussion

The stringent response is a global regulatory system, which mediates major changes in gene expression in response to growth-limiting stress conditions. Because, polyhydroxyalkanoates accumulation is a central feature of survival physiology when cells are stressed, it was hypothesized that these two mechanisms are linked. A set of cultivations performed both in flask cultures and in a bioreactor showed that a P. putida KT2400 mutant with non functional relA/spoT genes is able to produce and accumulate mcl-PHAs. The result of this examination is surprising in the light of observations made by Brigham et al. (2012), who showed that poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) is regulated by the stringent response in R. eutropha H16. In their study, a R. eutropha spoT2 mutant accumulated no detectable PHB under conditions of nitrogen starvation, confirming the hypothesis that guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp) plays an important role in the production of PHB. A possible relationship between the stringent response and PHB utilization was shown previously by Ruiz et al. (2001) in P. oleovorans GPo1. ATP and ppGpp levels increase concomitantly with PHAs degradation in P. oleovorans cells. It was postulated that ppGpp is an activator of RpoS synthesis that controls the genes involved in PHB metabolism (Ruiz et al. 2001; Brigham et al. 2012). Here, we show that nitrogen limitation positively influences mcl-PHAs synthesis both in the wild strain and the rpoN mutant of P. putida, but in RpoN-independent manner as it was shown by Hoffmann and Rehm (2004). Although this observation suggests that this process is dependent mainly on nitrogen availability, nitrogen limitation did not change the efficiency of mcl-PHAs synthesis in the relA/spoT mutant. Under the stress conditions, in the wild type cells, elevated amount of ppGpp would destabilize RNA polymerase complexes with housekeeping sigma factor promoting transcription from stress related promoters that depend on alternative sigma factors with lower affinity to core RNA polymerase. In this situation, as a result of ppGpp-deficiency due to the mutations, the transcription from the stress-responsive promoters can be impaired, partially due to the insufficient pool of free RNA polymerase core molecules that could bind to other σ factors related to stress tolerance, such as RpoN or RpoS (Potrykus and Cashel 2008).

In the flask culture experiment, the transcription of the genes directly involved in mcl-PHAs synthesis and degradation differed depending on the strain of bacteria and on the availability of nitrogen. The transcription of phaC1 and phaC2 were similar in all strains in both conditions. This observation is in contrary to results of Hoffmann and Rehm (2005) who showed that phaC1 gene expression was slightly induced in P. putida KT2440 under nitrogen starvation when sodium gluconate was used. Transcription of phaZ was significantly upregulated in P. putida KT2440 wild-type under both optimal and nitrogen limiting conditions. It could be suggested that both mutants do not effectively activate processes leading to recovery of energy from PHAs. The number of transcripts of phaC1, phaZ, phaC2 and phaD differed significantly from those of phaF and phaI, which indicates that these operons are differentially regulated, as in de Eugenio et al. (2010). According to previous studies (Klinke et al. 2000; de Eugenio et al. 2010), the phaD gene acts as an activator of the phaC1 and phaI promoters. In our study, however, phaC1 was not induced by high expression of phaD gene in wild type of P. putida KT2440 under nitrogen limiting conditions. On the contrary, obtained results support the possible regulation of the phaI promoter by phaD, which controls the phaI and phaF gene (Prieto et al. 1999). This was reflected in the higher expression of the phaI and phaF genes by this strain under nitrogen limitation than under optimal conditions. Because the expression of phaD gene was highest in the wild type strain cultivated under nitrogen limiting conditions, it could be suggested that this gene induction is dependent on nitrogen availability. In rpoN mutant the difference in phaD gene expression was smaller between conditions, therefore phaI and phaF genes expression difference between conditions was also smaller. Because the expression level of phaD gene was much lower in rpoN mutant than in wild type under nitrogen limiting conditions it could be speculated that a regulation of this gene could be RpoN dependent. Accordingly to Hoffmann and Rehm (2005), RpoN might be a negative regulator of phaF transcription, particularly when excess nitrogen is available, however it was not observed in our study because the expression of phaF gene was at the same level both in wild type and rpoN mutant. In a case of relA/spoT mutant, phaD gene expression was independent on the used conditions. It is worth emphasizing that, in the relA/spoT mutant, the phaI/phaF genes expression was at comparable level in both conditions. Expression of these genes in relA/spoT mutant was significantly higher than in wild-type strain and rpoN mutant, which could suggest that this operon is regulated by the stringent response in negative manner.

RNA-seq analysis revealed that genes directly involved in mcl-PHAs synthesis and degradation in relA/spoT mutant during cultivation in bioreactor did not show statistically significant changes in transcription between exponential growth and stationary phase. Similarly to the results obtained by Poblete-Castro et al. (2012) and Fu et al. (2015), the highest upregulation was noticed for phaI and phaF genes. In the mentioned reports, as well as in this study, upregulation of phaI was higher, that confirm superiority of phaI in relation to phaF gene (de Eugenio et al. 2010). The higher induction of phaI/phaF operon in comparison to phaC1/phaZ/phaC2/phaD operon, as well as its significantly higher transcription in flasks culture confirms both independent regulation of phaI/phaF genes, and possible negative influence of stringent response on these genes expression. The highest upregulation (5.9 fold-change) showed phaG gene linking fatty acid de novo biosynthesis with PHAs biosynthesis when non-related carbon sources are utilized (Hoffmann and Rehm 2004). The flasks culture showed that its transcription was nitrogen dependent but RpoN-independent. The same observation was previously made by Hoffman and Rehm (2004), when sodium gluconate was used as a carbon source. However, in this work oleic acid was used as the only carbon source, therefore high induction of this gene is surprising. In order to prove this observation phaG gene transcription was examined at six time-points during relA/spoT mutant cultivation in bioreactor using reverse transcription real-time PCR. Obtained results showed gradual increase of this gene transcription until 41 h of cultivation, confirming the results from RNA-seq. It seems that this gene must have (an) additional function(s) in P. putida KT2440 metabolism.

Global transcriptomics of the relA/spoT mutant revealed that only some regulatory genes showed upregulation although these changes were not statistically significant. During the stationary phase the highest activation was shown by genes coding for NtrC transcriptional regulator (fold-change 8.8) and an undetermined gene coding for a transcriptional regulator from TetR family (fold-change 13.2). NtrC, a global regulator, activates the transcription of many genes for the uptake and catabolism of various nitrogen sources and should be activated only during nitrogen limitation (Chubukov et al. 2014). NtrC activated relA gene during nitrogen starvation, therefore it is accepted that NtrC couples nitrogen starvation stress and stringent response (Brown et al. 2014). One of the other genes regulated by NtrC is glnK. The PII-like protein that is produced by this gene regulates multiple cellular functions related to nitrogen metabolism, including ammonium transport and assimilation via glutamine synthetase, nitrogen fixation and nitrogen-responsive transcriptional regulation, by means of protein–protein interactions (García-González et al. 2009). Our results showed its upregulation, which is in accordance with the results of Poblete-Castro et al. (2012). In their work glnK showed a large change in both mRNA abundance and protein level when P. putida was subjected to dual limitation of nitrogen and carbon.

One of the regulators specific to the stationary phase is highly conserved bacterial protein Lrp (leucine-responsive regulatory protein), which can act both as a transcriptional repressor and activator (Pletnev et al. 2015) influencing on more than 400 genes in E. coli. Among them there are genes responsible for amino acid synthesis, catabolism and the utilization of various carbon sources (Tani et al. 2002). Most probably, Lrp is upregulated by ppGpp in P. putida KT2440 like in E. coli, which would explain the fact that the increase in abundance of Lrp transcripts during the transition to the stationary phase was not significant.

The RpoS factor, encoded by rpoS, activates the transcription of genes involved in the bacterial general stress response. Therefore, it was expected that the number of rpoS gene transcripts will increase entering stationary phase. However, the number of rpoS gene transcripts did not increase in the relA/spoT mutant; the same was observed with the rpoN and rpoD genes. The observed relation between rpoS expression and the stringent response is in agreement with previous reports. For instance, high ppGpp levels resulted in increased rpoS transcription in E. coli (Gentry et al. 1993), and the P. aeruginosa relA mutant strain, which synthesizes less ppGpp than the wild type, had reduced but not abolished RpoS protein levels (Erickson et al. 2004). In E. coli, poor induction of the RpoS regulon in the ppGpp-null mutant likely results from lower induction of the rpoS gene, weak stabilization of RpoS by IraP, and poor competition of core RNAP for RpoS (Traxler et al. 2008).

The Crc (catabolite repression control) protein is a key regulator involved in the repression by catabolites in Pseudomonas at translational level. Generally, the action of Crc is limited to the exponential growth phase and it is not observed when the cultures entered into the stationary phase (La Rosa et al. 2014). In our study the number of mRNA transcripts of Crc decreased in the stationary phase, but they were still present, most likely reducing mcl-PHAs synthesis by repressing phaC1 translation.

The gene whose expression was upregulated the most was a transcriptional regulator from the TetR family (PP_2475) (fold change 13.2). Follonier et al. (2013) found that when P. putida KT2440 was grown in medium supplemented with octanoate, the same gene was upregulated to a much lesser extent under elevated total pressure and elevated oxygen pressure (fold change of 1.59 and 1.7, respectively). A similar upregulation (1.56 fold-change) of a TetR family transcriptional regulator was shown by Fu et al. (2015) for P. putida LS46 grown on waste fatty acid but not on glycerol. The authors postulated that this factor is responsible for short chain fatty acid degradation.

In this study 104 genes were significantly differentially expressed between exponential growth and stationary phase. Most of them were responsible for the expression of the branched-chain amino acid ABC transporters and proteins engaged in nitrogen metabolism. Similar observation was made by Poblete-Castro et al. (2012) when wild-type of P. putida KT2440 was grown under nitrogen-limitation. Authors observed that expression of the branched-chain amino acid ABC transporter was up to 16-fold higher as a result of stress. Other upregulated genes were responsible for the urea assimilation system (e.g. UreE, UreJ, and UreA). The activation of urease may increase competitive fitness of bacteria under nitrogen-limiting conditions, since urease catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea to yield ammonia. According to Poblete-Castro et al. (2012) the same system was activated both under nitrogen limitation and under carbon–nitrogen dual limitation. However, our examination showed that upregulation of the genes responsible for branched-chain amino acid ABC transporters and nitrogen metabolism was much stronger than in the above mentioned paper. The transcription of genes coding for branched-chain amino acid ABC transporters was even more than 100 times higher in the stationary phase (utrA). Similarly, nitrogen metabolism related genes showed more than 100 times higher activity in the stationary phase (e.g. nirD). The differences in gene transcription between exponential growth and the stationary phase in the relA/spoT mutant were unexpectedly high in comparison to values obtained by other authors for P. putida KT2440 (Poblete-Castro et al. 2012; Follonier et al. 2013). It is postulated that most of the highly upregulated genes are stringent response dependent. This group comprises genes coding for branched-chain amino acid ABC transporters and nitrogen metabolism. Especially, glnK gene coding for nitrogen regulatory protein P-II showed unusually high number of transcripts in the stationary phase (RPKM = 47668.9). This hypothesis could be supported by results obtained for Corynebacterium glutamicum (Brockmann-Gretza and Kalinowski 2006). In this study, the C. glutamicum rel mutant was used to reveal genes controlled by the stringent response. According to the results obtained by Brockmann-Gretza and Kalinowski (2006), many genes coding for branched-chain amino acid ABC transporters and nitrogen metabolism were negatively controlled by the stringent response. High expression of phaI and phaF genes observed during the experiment in flasks suggests that these PHA granule associated proteins can be also negatively regulated by ppGpp. Other genes are positively affected by the stringent response. Among them are genes involved in global regulation, with rpoS being the most important (Brockmann-Gretza and Kalinowski 2006). RpoS controls the general stress response therefore it plays an important role in adaptation to nutritional and environmental stress. In contrary to P. putida deficient in stringent response examined in this study, RpoS expression in the wild type strain is increasing during transition from exponential growth to stationary phase when ppGpp are at the sufficient level. Similar behaviour was observed in the case of genes encoding Lpr, PsrA and GacA transcriptional regulators, that are likely positively affected by stringent response. It is known that psrA and gacA are involved in rpoS activation (Venturi 2003), thus RpoS is additionally restricted. The stringent response deficiency makes cellular metabolism disordered by transcriptional regulators deactivation, and therefore cells are much more unbalanced in a stressful environment.

In conclusion, we showed that the P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant is able to accumulate mcl-PHAs, therefore it could be postulated that the stringent response is not necessary for polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesis using oleic acid as an external carbon source. The composition of mcl-PHAs monomers was similar to that of mcl-PHAs synthesized by other Pseudomonas species using fatty acids. Comparative analysis showed that nitrogen limitation did not influence mcl-PHAs synthesis, suggesting that the global regulator did not act properly in the studied mutant. Expression of phaI/phaF genes in the relA/spoT mutant was significantly higher than in the wild type strain and the rpoN mutant, which suggests that this operon is negatively regulated by the stringent response. The small changes in mcl-PHAs related genes between the exponential growth and stationary phases can be due to the fact that they are activated more or less directly by the RpoS global regulator. Surprisingly, the substantial activation of the phaG gene was observed. RNA-seq analysis showed that the transition from exponential growth to the stationary phase caused significant changes in genes encoding the branched-chain amino acid ABC transporters and proteins engaged in nitrogen metabolism. Most of these genes were upregulated, confirming that the stringent response affected their transcription negatively in P. putida KT2440. Transcriptional regulators, including rpoS, rpoN and rpoD, did not show changes when entering the stationary phase, therefore it could be suggested that they are influenced positively by stringent response. Although global regulation was non-functioning in the P. putida KT2440 relA/spoT mutant, mcl-PHAs synthesis was made possible by the activity of other transcriptional factors that remain to be determined.

Authors’ contributions

JMC participated in the design of the study and carried out the molecular studies, and RNAseq data analysis as well as drafted manuscript. DD performed the experiments. ASzP helped to draft manuscript and gave some interpretation on data. SC participated in the design of the study, supervised the work and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Tomasz Pokój for his help on polyhydroxyalkanoates analysis using gas chromatography.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article (and its supporting material).

Funding

This work was financed by National Science Centre (Poland) under Project Number 2012/05/B/NZ1/00011.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- PHA

polyhydroxyalkanoates

- mcl-PHA

medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates

- PHB

poly(3-hydroxybutyrate)

- P. putida

Pseudomonas putida

- ppGpp

guanosine tetraphosphate

- (p)ppGpp

guanosine pentaphosphate

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- CDW

cell dry weight

- GC

gas chromatography

- TOC

total organic carbon

- RIN

RNA integrity number

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- FDR

false discovery rate

- RPKM

Reads Per Kilobase per Million

- 3HB

3-hydroxybutyrate

- 3HHx

3-hydroxyhexanoate

- 3HO

3-hydroxyoctanoate

- 3HN

3-hydroxynonanoate

- 3HD

3-hydroxydecanoate

- 3HUD

3-hydroxyundecanoate

- 3HDD

3-hydroxydodecanoate

- 3HTD

3-hydroxytetradecanoate

- 3HHxD

3-hydroxyhexadecanoate

- n.d.

not detected

- C. glutamicum

Corynebacterium glutamicum

Additional file

Additional file 1: TableS1. Significantly differentially expressed genes in the stationary phase (41 h) with adjusted p-value (Adj. p-value) lower than 0.05. The genes are sorted according to fold-change.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13568-017-0396-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Justyna Mozejko-Ciesielska, Phone: (+48) (89) 5234234, Email: justyna.mozejko@uwm.edu.pl.

Dorota Dabrowska, Email: dorota.dabrowska@uwm.edu.pl.

Agnieszka Szalewska-Palasz, Email: agnieszka.szalewska-palasz@biol.ug.edu.pl.

Slawomir Ciesielski, Email: slawomir.ciesielski@uwm.edu.pl.

References

- Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson GC, Tenson T, Hauryliuk V. The RelA/SpoT homolog (RSH) superfamily: distribution and functional evolution of ppGpp synthetases and hydrolases across the tree of life. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayub ND, Tribelli PM, López NI. Polyhydroxyalkanoates are essential for maintenance of redox state in the Antarctic bacterium Pseudomonas sp. 14-3 during low temperature adaptation. Extremophiles. 2009;13:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s00792-008-0197-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigham CJ, Speth DR, Rha C, Sinskey AJ. Whole-genome microarray and gene deletion studies reveal regulation of the polyhydroxyalkanoate production cycle by the stringent response in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:8033–8044. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01693-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann-Gretza O, Kalinowski J. Global gene expression during stringent response in Corynebacterium glutamicum in presence and absence of the rel gene encoding (p)ppGpp synthase. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:230–245. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR, Barton G, Pan Z, Buck M, Wigneshweraraj S. Nitrogen stress response and stringent response are coupled in Escherichia coli. Nat Commun. 2014;5:155–176. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubukov V, Gerosa L, Kochanowski K, Sauer U. Coordination of microbial metabolism. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:327–340. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielski S, Mozejko J. Pisutpaisal N (2015) Plant oils as promising substrates for polyhydroxyalkanoates production. J Clean Prod. 2015;106:408–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielski S, Mozejko J, Przybylek G. The influence of nitrogen limitation on mcl-PHA synthesis by two newly isolated strains of Pseudomonas sp. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;37:511–520. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0698-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottyn B, Baeyen S, Pauwelyn E, Verbaendert I, De Vos P, Bleyaert P, Höfte M, Maes M. Development of a real-time PCR assay for Pseudomonas cichorii, the causal agent of midrib rot in greenhouse-grown lettuce, and its detection in irrigating water. Plant Pathol. 2011;60:453–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02388.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Eugenio LI, Galán B, Escapa IF, Maestro B, Sanz JM, García JL, Prieto MA. The PhaD regulator controls the simultaneous expression of the pha genes involved in polyhydroxyalkanoate metabolism and turnover in Pseudomonas putida KT2442. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:1591–1603. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz E, Prieto MA. Bacterial promoters triggering biodegradation of aromatic pollutants. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2000;11:467–475. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson DL, Lines JL, Pesci EC, Venturi V, Storey DG. Pseudomonas aeruginosa relA contributes to virulence in Drosophila melanogaster. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5638–5645. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5638-5645.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follonier S, Escapa IF, Fonseca PM, Henes B, Panke S, Zinn M, Prieto MA. New insights on the reorganization of gene transcription in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 at elevated pressure. Microb Cell Fact. 2013;12:30–48. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Sharma P, Spicer V, Krokhin OV, Zhang X, Fristensky B, Cicek N, Sparling R, Levin DB. Quantitative omics analyses of medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanaote metabolism in Pseudomonas putida LS46 cultured with waste glycerol and waste fatty acids. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0142322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-González V, Jiménez-Fernández A, Hervás AB, Canosa I, Santero E, Govantes F. Distinct roles for NtrC and GlnK in nitrogen regulation of the Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP cyanuric acid utilization operon. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;300:222–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry DR, Hernandez VJ, Nguyen LH, Jensen DB, Cashel M. Synthesis of the stationary-phase sigma factor sigma s is positively regulated by ppGpp. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7982–7989. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7982-7989.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann N, Rehm BHA. Regulation of polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;237:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2004.tb09671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann N, Rehm BHA. Nitrogen-dependent regulation of medium-chain length polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis genes in pseudomonads. Biotech Lett. 2005;27:279–282. doi: 10.1007/s10529-004-8353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinke S, De Roo G, Witholt B, Kessler B. Role of phaD in accumulation of medium-chain-length poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) in Pseudomonas oleovorans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3705–3710. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.9.3705-3710.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler T, Harayama S, Ramos JL, Timmis KN. Involvement of Pseudomonas putida RpoN sigma factor in regulation of various metabolic functions. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4326–4333. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4326-4333.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa R, de la Peña F, Prieto MA, Rojo F. The Crc protein inhibits the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates in Pseudomonas putida under balanced carbon/nitrogen growth conditions. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:278–290. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López NI, Pettinari MJ, Nikel PI, Méndez BS. Chapter Three—polyhydroxyalkanoates: much more than biodegradable plastics. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2015;93:73–106. doi: 10.1016/bs.aambs.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Gutiérrez JC, Henry S, Hallet S, Martin-Laurent F, Catroux G, Philippot L. Quantification of a novel group of nitrate-reducing bacteria in the environment by real-time PCR. J Microbiol Methods. 2004;57:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittenhuber G. Comparative genomics and evolution of genes encoding bacterial (p)ppGpp synthetases/hydrolases (the Rel, RelA and SpoT proteins) J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;3:585–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozejko J, Ciesielski S. Pulsed feeding strategy is more favorable to medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates production from waste rapeseed oil. Biotechnol Prog. 2014;30:1243–1246. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KE, Weinel C, Paulsen IT, Dodson RJ, Hilbert H, Martins dos Santos VAP, Fouts DE, Gill SR, Pop M, Holmes M, Brinkac L, Beanan M, DeBoy RT, Daugherty S, Kolonay J, Madupu R, Nelson W, White O, Peterson J, Khouri H, Hance I, Chris Lee P, Holtzapple E, Scanlan D, Tran K, Moazzez A, Utterback T, Rizzo M, Lee K, Kosack D, Moestl D, Wedler H, Lauber J, Stjepandic D, Hoheisel J, Straetz M, Heim S, Kiewitz C, Eisen JA, Timmis KN, Düsterhöft A, Tümmler B, Fraser CM. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the metabolically versatile Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ Microbiol. 2002;4:799–808. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletnev P, Osterman I, Sergiev P, Bogdanov A, Dontsova O. Survival guide: Escherichia coli in the stationary phase. Acta Nat. 2015;7:22–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poblete-Castro I, Escapa IF, Jäger C, Puchalka J, Chi Lam C, Schomburg D, Prieto M, Martins dos Santos VA. The metabolic response of P. putida KT2442 producing high levels of polyhydroxyalkanoate under single- and multiple-nutrient-limited growth: highlights from a multi-level omics approach. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:34–55. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier Y, Nawrath C, Somerville C. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates, a family of biodegradable plastics and elastomers, in bacteria and plants. Biotechnol (NY) 1995;13:142–150. doi: 10.1038/nbt0295-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potrykus K, Cashel M. (p)ppGpp: still magical? Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:35–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto MA, Hler BB, Jung K, Witholt B, Kessler B. PhaF, a polyhydroxyalkanoate-granule-associated protein of Pseudomonas oleovorans GPo1 involved in the regulatory expression system for pha genes. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:858–868. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.858-868.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz JA, Lopez NI, Fernandez RO, Mendez BS. Polyhydroxyalkanoate degradation is associated with nucleotide accumulation and enhances stress resistance and survival of Pseudomonas oleovorans in natural water microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:225–230. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.225-230.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaiman DK, Ashby RD, Foglia TA. Rapid and specific identification of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase gene by polymerase chain reaction. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;53:690–694. doi: 10.1007/s002530000332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze CC, Bernardo LMD, Shingler V. Integration of global regulation of two aromatic-responsive sigma(54)-dependent systems: a common phenotype by different mechanisms. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:760–770. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.3.760-770.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani TH, Khodursky A, Blumenthal RM, Brown PO, Matthews RG. Adaptation to famine: a family of stationary-phase genes revealed by microarray analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13471–13476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212510999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traxler MF, Summers SM, Nguyen H-T, Zacharia VM, Hightower GA, Smith JT, Conway T. The global, ppGpp-mediated stringent response to amino acid starvation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:1128–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venturi V. Control of rpoS transcription in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas: why so different? Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article (and its supporting material).