Abstract

Background

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are linked to metastatic relapse and are regarded as a prognostic marker for human cancer. High expression of plakoglobin, a cell adhesion protein, within the primary tumor is positively associated with CTC clusters in breast cancer. In this study, we investigated the correlation between plakoglobin expression and survival of breast cancer.

Methods

We evaluated 121 breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Expression of plakoglobin was identified by immunohistochemical staining in the cell membrane. We also examined the relation between the expression of plakoglobin and E-cadherin, an epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) marker.

Results

Patients with high plakoglobin expression had significantly worse distant-metastasis-free survival (DMFS) (P = 0.016, log rank). Plakoglobin expression had no correlation with pathological complete response rate (P = 0.627). On univariate analysis with respect to distant metastasis, high plakoglobin expression showed worse prognosis than low plakoglobin expression [P = 0.036, hazard ratio (HR) = 3.719]. Multivariate analysis found the same result (P = 0.013, HR = 5.052). In addition, there was a significant relationship between the expression of plakoglobin and E-cadherin (P = 0.023).

Conclusions

Plakoglobin expression is an independent prognostic factor in patients with breast cancer, particularly for DMFS, and this is related to EMT.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40364-017-0099-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Plakoglobin, Circulating tumor cells, Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Breast cancer, Predictive marker

Background

Breast cancer is the most common and deadly form of cancer worldwide in women. Although treatment with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) increases the rate of breast-conserving surgery and reduces the risk of postoperative recurrence in patients with resectable breast cancer [1–4], recurrence and metastasis remain major problems for cure [5]. NAC requires tailoring; particularly by exploring biomarkers using genetic approaches or establishing therapeutic strategies based on the response to early treatment.

Haematogenous metastasis occurs by circulating tumor cells (CTCs) that detach from primary tumor tissues and circulate in the bloodstream and reach distant sites after extravasation [6]. CTCs are regarded as a useful prognostic marker in patients with breast cancer [7]. Some studies reported that clusters of CTCs were detected within the circulation of patients with metastatic epithelial cancers, and that those clusters had greater metastatic potential than single CTCs [8]. Cell–cell adhesion is a determinant of CTCs in single or clustered cells, and plakoglobin, a cell adhesion protein, is a key mediator of tumor-cell clustering, which is expressed in a heterogeneous pattern within the primary tumor [8]. High plakoglobin expression enables tumor cells to stick together and move in clusters in the bloodstream, allowing more chance of metastasis and resulting in worse survival of breast cancer [9]. Also, tumor cells with high plakoglobin levels show low motility and result in the inhibition of invasion [10].

The association between plakoglobin and malignancy remains controversial. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is observed when cancer spreads, and promotes cancer infiltration and metastasis by facilitating cancer cell motility and breakdown of the extracellular matrix [11]. Plakoglobin is related to EMT, because it can be a linker between E-cadherin and α-catenin in cell–cell adhesion [12]. Insufficient expression of plakoglobin could therefore promote EMT [9]. In this study, we aimed to evaluate plakoglobin as a possible marker for predicting outcome and treatment response in breast cancer, and to investigate the relationship between plakoglobin and E-cadherin expression.

Methods

Patient background

A total of 121 patients with resectable, early-stage breast cancer diagnosed as stage IIA (T1, N1, M0 or T2, N0, M0), IIB (T2, N1, M0 or T3, N0, M0), or IIIA (T1–2, N2, M0 or T3, N1–2, M0) were treated with NAC between 2007 and 2013. Tumor stage and T and N factors were stratified based on the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, UICC 7th Edition [13]. Breast cancer was confirmed histologically by core needle biopsy and staged by systemic imaging studies using computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography (US), and bone scintigraphy. Breast cancer was classified into subtypes according to the immunohistochemical expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PgR), human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) 2, and Ki67.

All patients received a standardised protocol of NAC consisting of four courses of FEC100 (500 mg m−2 fluorouracil, 100 mg m−2 epirubicin, and 500 mg m−2 cyclophosphamide) every 3 weeks, followed by 12 courses of 80 mg m−2 paclitaxel administered weekly [14, 15]. Thirty-five patients had HER2-positive breast cancer and were additionally administered weekly (2 mg kg−1) or tri-weekly (6 mg kg−1) trastuzumab during paclitaxel treatment [16]. All patients underwent chemotherapy as outpatients. Therapeutic anti-tumor effects were assessed according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria [17]. Pathological complete response (pCR) was defined as the complete disappearance of the invasive component of the lesion, with or without intraductal components, including in the lymph nodes. Patients underwent mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery after NAC. All patients who underwent breast-conserving surgery were administered postoperative radiotherapy to the remnant breast. Overall survival (OS) time was the period from the initiation of NAC to the time of death from any cause. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as freedom from all local, locoregional, and distant recurrences. Distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) time was defined as time to distant metastasis or death if the latter event occurred before a distant metastasis was diagnosed. All patients were followed up by physical examination every 3 months, US every 6 months, and CT and bone scintigraphy annually. The median follow-up period for the assessment of OS was 3.5 years (range, 0.6–7.6 years), 3.3 years (range, 0.1–7.6 years) for DFS, and 3.4 years (range, 0.1–7.6 years) for DMFS.

This study was conducted at Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka, Japan, according to the Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker prognostic Studies (REMARK) guidelines and a retrospectively written research, pathological evaluation, and statistical plan. The design of this study is a retrospective chart review study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This research conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki of 2013. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Osaka City University (#926).

Immunohistochemistry

All patients underwent a core needle biopsy prior to NAC, and they underwent curative surgery involving mastectomy or conservative surgery with axillary lymph node dissection after NAC. Immunohistochemical studies were performed as previously described on core needle biopsy specimens [18, 19]. Tumor specimens were fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution and embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm-thick sections were mounted on glass slides. Slides were deparaffinised in xylene and heated for 20 min (105 °C, 0.4 kg m−2) in an autoclave in Target Retrieval Solution (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Specimens were incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 15 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity, and then incubated in 10% normal goat or rabbit serum to block non-specific reactions.

Primary monoclonal antibodies directed against ER (clone 1D5, dilution 1:80; Dako), PgR (clone PgR636, dilution 1:100; Dako), HER2 (HercepTest™; Dako), Ki67 (clone MIB-1, dilution 1:00; Dako), plakoglobin (clone 4C12, dilution 1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), E-cadherin (clone #3195, dilution 1:400; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and β-catenin (clone #9562, dilution 1:400; CST, Danvers, USA) and were used. Tissue sections were incubated with each antibody for 70 min at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C, and then with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin secondary antibodies (HISTOFINE (PO)™ Kit; Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan). Slides were subsequently treated with streptavidin–peroxidase reagent and incubated in phosphate-buffered saline–diaminobenzidine and 1% hydrogen peroxide (v/v), followed by counterstaining with Mayer’s haematoxylin. Positive and negative controls for each marker were used according to the supplier’s data sheet.

Immunohistochemical scoring

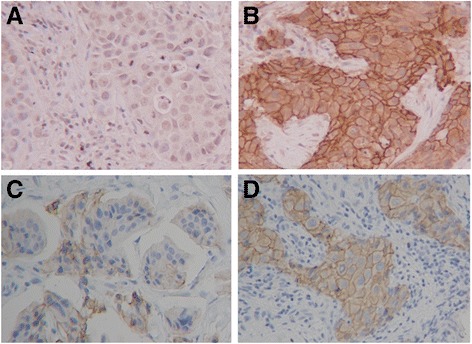

Immunohistochemical scoring was performed by two pathologists specialised in mammary gland pathology, using the blind method to confirm the objectivity and reproducibility of diagnosis. The cutoffs for ER and PgR positivity were both ≥1% positive tumor cells with nuclear staining [20]. Tumors with 3+ HER2 on immunohistochemical staining were considered to show HER2 overexpression; tumors with 2+ HER2 were further analysed by fluorescence in situ hybridisation; and those with HER2/ centromeric probe for chromosome (CEP) 17 ≥ 2.0 were also considered to exhibit HER2 overexpression [21]. A Ki67-labeling index ≥14% tumor cells with nuclear staining was determined to be positive [22]. To evaluate plakoglobin, E-cadherin and β-catenin expression, three fields of view (FOVs) in darkly stained areas were selected, and the percentage of cancer cells showing membrane positivity in each FOV was measured microscopically at 400× magnification. The value of plakoglobin expression was categorised as follows: 0 = no cells; 1+ = 1–25% cells (Fig. 1a ); 2+ = 26–75% of cells; and 3+ = >75% of cells (Fig. 1b ) [23]. Plakoglobin expression was considered high if the score was 3, and low when score was ≤2. The value of E-cadherin expression was categorised as follows: 0 = no cells; 1+ = 1–30% of cells (Fig. 1c ); 2+ = 31–70% of cells; and 3+ = >70% of cells (Fig. 1d ) [24, 25]. E-cadherin expression was considered high if the score was ≥2, and low when the score was ≤1. β-catenin expression was considered high if cells were ≥30% (Additional file 1: Figure S1A), and low when cells were <30% (Additional file 1: Figure S1B).

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical determination of plakoglobin and E-cadherin. Plakoglobin and E-cadherin were observed at cell–cell boundaries of breast cancer cells. Plakoglobin expression was categorised as follows: 0 = no cells; 1+ = 1–25% of cells (a); 2+ = 26–75% of cells; 3+ = >75% of cells (b). E-cadherin expression was categorised as follows: 0 = no cells; 1+ = 1–30% of cells (c); 2+ = 31–70% of cells; 3+ = >70% of cells (d) (400×)

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP11 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The associations between plakoglobin, E-cadherin and clinicopathological variables were evaluated using the χ2 test (or Fisher’s exact test when necessary). The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate OS, DFS and DMFS. The association with survival was analysed by Kaplan–Meier plot and log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to compute univariate and multivariate hazards ratios (HRs) for the study parameters with 95% confidence interval (CI). A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Clinicopathological response of primary breast cancer to NAC

The subtype in 121 patients who received NAC was triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) in 39 (32.2%) patients and non-TNBC in 82 (67.8%) patients. Regarding treatment response, 48 (39.7%) patients had a pCR, and 73 (60.3%) had a non-pCR. According to subtype, 19 (48.7%) TNBC patients and 29 (35.4%) non-TNBC patients had a pCR (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Plakoglobin and E-cadherin expression in all breast cancer

There were 21 (17.4%) patients with high plakoglobin expression (score: 3) and 100 (82.6%) with low plakoglobin expression (score: ≤2). There were 71 (58.7%) patients with high E-cadherin expression (score: ≥2) and 50 (41.3%) with low E-cadherin expression (score: ≤1).

Evaluation based on clinicopathological features showed that plakoglobin was significantly correlated with E-cadherin (P = 0.023) (Table 1 ). There was no significant correlation between plakoglobin and any other tested clinicopathological parameter, including pCR (P = 0.627). Patients with low E-cadherin expression had a significantly higher rate of TNBC (P = 0.003), and patients with high E-cadherin expression in TNBC tended to have a high pCR rate (P = 0.105) (Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Correlation between clinicopathological features and plakoglobin and E-cadherin expression in 121 patients with breast cancer

| Parameters | plakoglobin | p value | E-cadherin | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (n = 21) | Low (n = 100) | High (n = 71) | Low (n = 50) | |||

| HR and HER2 status | ||||||

| TNBC | 4 (19.0%) | 35 (35.0%) | 0.203 | 15 (21.1%) | 24 (48.0%) | 0.003 |

| non-TNBC | 17 (81.0%) | 65 (65.0%) | 56 (78.9%) | 26 (52.0%) | ||

| HER2 status | ||||||

| negative | 16 (76.2%) | 70 (70.0%) | 47 (66.2%) | 39 (78.0%) | 0.222 | |

| positive | 5 (23.8%) | 30 (30.0%) | 0.792 | 24 (33.8%) | 11 (22.0%) | |

| Age at operation | ||||||

| ≤ 56 | 12 (57.1%) | 45 (45.0%) | 0.344 | 34 (47.9%) | 23 (46.0%) | 0.855 |

| > 56 | 9 (42.9%) | 55 (55.0%) | 37 (52.1%) | 27 (54.0%) | ||

| Menopause | ||||||

| Negative | 10 (47.6%) | 38 (38.0%) | 0.466 | 28 (39.4%) | 20 (40.0%) | 0.950 |

| Positive | 11 (52.4%) | 62 (62.0%) | 43 (60.6%) | 30 (60.0%) | ||

| Tumor size | ||||||

| ≤ 2 cm | 2 (9.5%) | 15 (15.0%) | 0.734 | 9 (12.7%) | 8 (16.0%) | 0.607 |

| > 2 cm | 19 (90.5%) | 85 (85.0%) | 62 (87.3%) | 42 (84.0%) | ||

| Lymph node status | ||||||

| Negative | 8 (38.1%) | 27 (27.0%) | 0.304 | 23 (32.4%) | 12 (24.0%) | 0.416 |

| Positive | 13 (61.9%) | 73 (73.0%) | 48 (67.6%) | 38 (76.0%) | ||

| Nuclear grade | ||||||

| 1, 2 | 16 (76.2%) | 78 (78.0%) | 0.857 | 54 (76.1%) | 40 (80.0%) | 0.663 |

| 3 | 5 (23.8%) | 22 (22.0%) | 17 (23.9%) | 10 (20.0%) | ||

| Ki67 | ||||||

| ≤ 14% | 6 (28.6%) | 45 (45.0%) | 0.225 | 30 (42.3%) | 21 (42.0%) | 0.978 |

| > 14% | 15 (71.4%) | 55 (55.0%) | 41 (57.7%) | 29 (58.0%) | ||

| Pathological response | ||||||

| pCR | 7 (33.3%) | 41 (41.0%) | 0.627 | 39 (54.9%) | 34 (68.0%) | 0.187 |

| non-pCR | 14 (66.7%) | 59 (59.0%) | 32 (45.1%) | 16 (32.0%) | ||

| Plakoglobin | ||||||

| Low | Not | Not | 54 (76.1%) | 46 (92.0%) | 0.023 | |

| High | determined | determined | 17 (23.9%) | 4 (8.0%) | ||

| E-cadherin | ||||||

| Negative | 4 (19.0%) | 46 (46.0%) | 0.023 | Not | Not | |

| Positive | 17 (81.0%) | 54 (54.0%) | determined | determined | ||

HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR hormone receptor; pCR pathological complete response; TNBC triple-negative breast cancer

Table 2.

Correlation between pCR and plakoglobin and E-cadherin expression in 39 TNBC and 82 non-TNBC.

| Parameters | plakoglobin | p value | E-cadherin | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (n = 4) | Low (n = 35) | High (n = 15) | Low (n = 24) | ||||

| TNBC (n = 39) |

Pathological response | ||||||

| pCR | 3 (75.0%) | 16 (45.7%) | 0.342 | 10 (66.7%) | 9 (37.5%) | 0.105 | |

| non-pCR | 1 (25.0%) | 19 (54.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 15 (62.5%) | |||

| non-TNBC (n = 82) |

High (n = 17) | Low (n = 65) | High (n = 56) | Low (n = 26) | |||

| Pathological response | |||||||

| pCR | 4 (23.5%) | 25 (38.5%) | 0.393 | 22 (39.3%) | 7 (26.9%) | 0.328 | |

| non-pCR | 13 (76.5%) | 40 (61.5%) | 34 (60.7%) | 19 (73.1%) | |||

pCR pathological complete response; TNBC triple-negative breast cancer

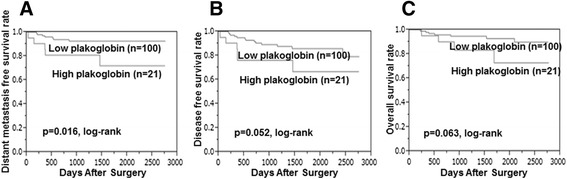

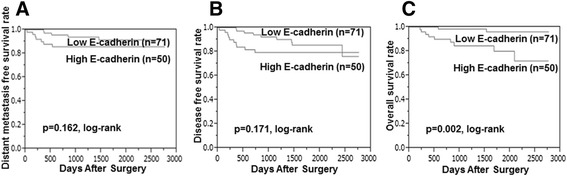

DMFS was significantly worse in patients with high compared with low plakoglobin expression (P = 0.016, log-rank) (Fig. 2a ). DFS and OS did not differ significantly between patients with low or high plakoglobin expression (P = 0.052, log rank) (P = 0.063, log rank) (Figs. 2b, c). OS was significantly longer in patients with high compared with low E-cadherin expression (P = 0.002, log rank), while DFS and DMFS tended to be longer in the high-E-cadherin group (P = 0.171, log rank) (P = 0.162, log rank) (Fig. 3a–c ).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier stratified by plakoglobin expression in breast cancer. DMFS was significantly worse in the high- compared with low-plakoglobin group (P = 0.016, log rank) (a). DFS and OS did not differ significantly between patients with low or high plakoglobin expression (P = 0.052, log rank) (b) (P = 0.063, log rank) (c). Abbreviations: DFS = disease-free survival; DMFS = distant-metastasis-free survival; OS = overall survival

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier stratified by E-cadherin expression in breast cancer. Compared with those with low E-cadherin, patients with high expression had superior overall survival (P = 0.002) (c), disease-free survival (P = 0.171) (b), and distant-metastasis-free survival (P = 0.162) (a)

The correlations between DMFS, OS and the various clinicopathological factors are shown in Table 3. According to the results of univariate analysis, DMFS exhibited significant relationships with age (P = 0.006), tumor size (P = 0.049) and plakoglobin (P = 0.036), and OS exhibited significant relationships with age (p = 0.020) and E-cadherin (P = 0.002). Multivariate analysis indicated that age (HR = 6.543, 95% CI: 1.563–47.40, P = 0.008), lymph node (HR = 7.035, 95% CI: 1.195–137.4, P = 0.028), nuclear grade (HR = 12.79, 95% CI: 1.591–163.3, P = 0.016), Ki67 (HR = 13.99, 95% CI: 2.063–203.4, P = 0.005), and plakoglobin (HR = 7.371, 95% CI: 1.596–44.23, P = 0.011) were independent prognostic factors for DMFS, and that age (HR = 6.525, 95% CI: 1.437–52.39, P = 0.013), nuclear grade (HR = 7.513, 95% CI: 1.047–84.10, P = 0.045), plakoglobin (HR = 8.232, 95% CI: 1.428–63.37, P = 0.019), and E-cadherin (HR = 15.62, 95% CI: 2.425–172.9, P = 0.003) were independent prognostic factor for OS (Additional file 3: Table S2).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis with respect to distant metastasis-free survival in 121 patients with breast cancer

| Parameter | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | ||

| Intrinsic subtype | TNBC vs non-TNBC | 1.053 | 0.281–3.344 | 0.933 | 0.632 | 0.137–2.710 | 0.535 |

| Intrinsic subtype | HER2 vs non-HER2 | 2.060 | 0.543–13.41 | 0.314 | 1.721 | 0.353–12.53 | 0.517 |

| Age at operation | ≤56 vs >56 | 6.096 | 1.606–39.67 | 0.006 | 6.543 | 1.563–47.40 | 0.008 |

| Tumor size (cm) | ≤2 vs >2 | 3.234 | 0.445–40.56 | 0.049 | 2.811 | 0.874–46.08 | 0.062 |

| Lymph node status | Negative vs Positive | 4.493 | 0.873–82.10 | 0.077 | 7.035 | 1.195–137.4 | 0.028 |

| Nuclear grade | 1–2 vs 3 | 1.805 | 0.482–5.730 | 0.353 | 12.79 | 1.591–163.3 | 0.016 |

| Ki67 (%) | ≤14 vs >14 | 2.048 | 0.652–6.942 | 0.218 | 13.99 | 2.063–203.4 | 0.005 |

| Pathological response | pCR vs non-pCR | 2.075 | 0.619–9.357 | 0.248 | 1.561 | 0.301–10.34 | 0.609 |

| plakoglobin | High vs Low | 3.719 | 1.100–11.66 | 0.036 | 7.371 | 1.596–44.23 | 0.011 |

| E-cadherin | Low vs High | 2.223 | 0.709–7.517 | 0.169 | 5.003 | 0.966–35.14 | 0.055 |

HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; CI confidence interval; pCR pathological complete response; TNBC triple-negative breast cancer

According to the results of univariate analysis, DMFS exhibited significant relationships with tumor size (P = 0.049) and plakoglobin (P = 0.036), and OS exhibited significant relationships with E-cadherin (P = 0.002). Multivariate analysis indicated that tumor size (>2) (HR = 5.511, 95% CI: 1.223–46.08, P = 0.032) and plakoglobin (HR = 5.052, 95% CI: 1.449–16.41, P = 0.013) were independent prognostic factors for DMFS, and that E-cadherin (HR = 8.045, 95% CI: 2.014–53.84, P = 0.002) was an independent prognostic factor for OS (Additional file 3: Table S2).

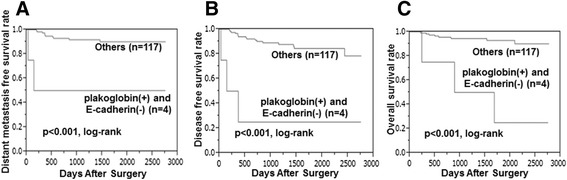

Combination of plakoglobin and E-cadherin

Only four patients had a combination of high plakoglobin and low E-cadherin expression. Compared with patients with other combinations, those with high plakoglobin and low E-cadherin expression had significantly worse OS (P < 0.001, log rank), DFS (P < 0.001, log rank), and DMFS (P < 0.001, log rank) (Fig. 4a–c).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier stratified by combination of plakoglobin and E-cadherin expression in breast cancer. Compared with those with high plakoglobin and low E-cadherin expression, patients with others had superior overall survival (P < 0.001) (c), disease-free survival (P < 0.001) (b), and distant-metastasis-free survival (P < 0.001) (a)

In addition, we evaluated β-catenin expression of patients with high plakoglobin and low E-cadherin expression. They all exhibited high β-catenin expression.

Discussion

Stephen Paget proposed in 1889 that cancer metastasis depends on the concept of “seed and soil”. With regard to the ability of the seed, the physical characteristics of single and clustered CTCs may also contribute to metastatic propensity [26]. CTC clusters are more rapidly cleared from the circulation than single CTCs, therefore, clusters account for only 2–5% of all observed CTCs. However, CTC clusters have 23–50 times greater metastatic potential than single CTCs; have more resistance to apoptosis than single CTCs; and contribute to shorter survival in patients with breast cancer [8]. Aceto et al. [8] found that CTC clusters had higher plakoglobin expression than single CTCs and that patients with high plakoglobin expression in primary tumors had significantly worse DMFS.

Plakoglobin (also known as γ-catenin) is a member of the Armadillo family of proteins and a homologue of β-catenin, and an important component of both the adherens junctions and desmosomes [27]. High plakoglobin expression makes tumor cells move in clusters in the circulation, which have a greater tendency to form distant metastasis than single CTCs have [9]. Plakoglobin interacts directly with E-cadherin and plays a fundamental role as a link between desmosomal cadherin and the intermediate filament cytoskeletons [12]. Insufficient desmosomal assembly leads to cytoskeletal reorganisation and loss of polarity of epithelial cells, thereby promoting EMT [28, 29]. This study also showed that patients with low plakoglobin expression had a significantly longer DMFS, and patients with high plakoglobin expression had significantly higher E-cadherin expression.

However, unlike plakoglobin, high E-cadherin expression was an independent prognostic factor. Therefore, the combination of low E-cadherin and high plakoglobin expression meant that EMT was promoted and there were more CTC clusters. Although only a few patients had that combination, they had remarkably high metastatic potential and poor outcome. Also, patients with low E-cadherin expression had a significantly higher rate of TNBC. Some studies demonstrated that Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation was preferentially found in TNBC [30, 31]. Though there was no significant correlation between plakoglobin and TNBC, patients with high plakoglobin and low E-cadherin expression all exhibited high β-catenin expression. It suggests that the reason why the combination of high plakoglobin and low E-cadherin expression induced significantly poor outcome may relate to Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation.

Emerging evidence suggests that EMT contributes to chemoresistance [32, 33]. The present study also showed that patients with high E-cadherin expression in TNBC tended to have a high pCR rate. However, plakoglobin expression did not significantly affect response to NAC in breast cancer. This may be because plakoglobin is not only involved in cell adhesion. It has been reported that plakoglobin plays both positive and negative roles in diverse malignancies [34–36]. It suggests that the microenvironment and the activated signalling pathways decide whether plakoglobin acts as an oncogene or tumor suppressor. In other words, the correlation between high plakoglobin expression and more distant metastatic potential of breast cancer may have nothing to do with either oncogene or tumor suppressor. While E-cadherin is one of EMT-markers, it is thought that plakoglobin is more useful prognostic factor for distant metastasis. As a potential limitation, the sample size of our study was small, and the numbers of combination of high plakoglobin and low E-cadherin expression were thus even smaller.

Conclusions

In conclusion, plakoglobin expression in primary tumor is useful as a biomarker to predict DMFS in breast cancer. It may offer an opportunity for therapeutic intervention. Further studies are therefore warranted to investigate which transcription factors regulate the expression of plakoglobin.

Additional files

Immunohistochemical determination of β-catenin was observed at cell–cell boundaries of breast cancer cells. β-catenin expression was considered high if cells were ≥30% (A), and low when cells were <30% (B) (400×). (TIFF 505 kb)

Clinical response rate and pathological response rate to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. (DOCX 11 kb)

Univariate and multivariate analysis with respect to overall survival in 121 patients with breast cancer. (DOCX 14 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Yayoi Matsukiyo and Tomomi Ohkawa (Department of Surgical Oncology, Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine) for helpful advice regarding data management.

Funding

This study was supported in part by Grants-in Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI, Nos. 25,461,992 and 26,461,957) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture and Technology of Japan.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in the preparation of this manuscript. WG collected the data, and wrote the manuscript. SK, YA, KTakada, KTakahashi, TH and TT performed the operation and designed the study. WG, SK and ST summarized the data and revised the manuscript. MOhsawa performed the pathological diagnosis. HM, KH and MOhira substantial contribution to the study design, performed the operation, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. This research conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki in 2013. All patients were informed of the investigational nature of this study and provided their written, informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Osaka City University (#926).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- CEP

Centromeric probe for chromosome

- CI

Confidence interval

- CT

Computed tomography

- CTC

Circulating tumor cells

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- DMFS

Distant-metastasis-free survival

- EMT

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- FOV

Fields of view

- HER

Human epidermal growth factor receptor

- HR

Hazards ratios

- NAC

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- OS

Overall survival

- pCR

Pathological complete response

- PgR

Progesterone receptor

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- REMARK

Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker prognostic Studies

- TNBC

Triple negative breast cancer

- US

Ultrasonography

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40364-017-0099-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Wataru Goto, Email: saraikazemaru@gmail.com.

Shinichiro Kashiwagi, Phone: (+81) 6-6645-3838, Email: spqv9ke9@view.ocn.ne.jp.

Yuka Asano, Email: asnyk0325@yahoo.co.jp.

Koji Takada, Email: taka.cl22.kou.sp@gmail.com.

Katsuyuki Takahashi, Email: k.taka@med.osaka-cu.ac.jp.

Takaharu Hatano, Email: hatano@med.osaka-cu.ac.jp.

Tsutomu Takashima, Email: tsutomu-@rd5.so-net.ne.jp.

Shuhei Tomita, Email: tomita.shuhei@med.osaka-cu.ac.jp.

Hisashi Motomura, Email: motomurally@gmail.com.

Masahiko Ohsawa, Email: m-ohsawa@med.osaka-cu.ac.jp.

Kosei Hirakawa, Email: hirakawa@med.osaka-cu.ac.jp.

Masaichi Ohira, Email: masaichi@med.osaka-cu.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Mayer EL, Carey LA, Burstein HJ. Clinical trial update: implications and management of residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(5):110. doi: 10.1186/bcr1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sachelarie I, Grossbard ML, Chadha M, Feldman S, Ghesani M, Blum RH. Primary systemic therapy of breast cancer. Oncologist. 2006;11(6):574–589. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-6-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Hage JA, van de Velde CJ, Julien JP, Tubiana-Hulin M, Vandervelden C, Duchateau L. Preoperative chemotherapy in primary operable breast cancer: results from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of cancer trial 10902. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(22):4224–4237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.22.4224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolmark N, Wang J, Mamounas E, Bryant J, Fisher B. Preoperative chemotherapy in patients with operable breast cancer: nine-year results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and bowel project B-18. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001;30:96–102. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson RW, Allred DC, Anderson BO, Burstein HJ, Edge SB, Farrar WB, Forero A, Giordano SH, Goldstein LJ, Gradishar WJ, et al. Metastatic breast cancer, version 1.2012: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2012;10(7):821–829. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L, Riethdorf S, Wu G, Wang T, Yang K, Peng G, Liu J, Pantel K. Meta-analysis of the prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(20):5701–5710. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aceto N, Bardia A, Miyamoto DT, Donaldson MC, Wittner BS, Spencer JA, Yu M, Pely A, Engstrom A, Zhu H, et al. Circulating tumor cell clusters are oligoclonal precursors of breast cancer metastasis. Cell. 2014;158(5):1110–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu L, Zeng H, Gu X, Ma W. Circulating tumor cell clusters-associated gene plakoglobin and breast cancer survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;151(3):491–500. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rieger-Christ KM, Ng L, Hanley RS, Durrani O, Ma H, Yee AS, Libertino JA, Summerhayes IC. Restoration of plakoglobin expression in bladder carcinoma cell lines suppresses cell migration and tumorigenic potential. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(12):2153–2159. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139(5):871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukunaga Y, Liu H, Shimizu M, Komiya S, Kawasuji M, Nagafuchi A. Defining the roles of beta-catenin and plakoglobin in cell-cell adhesion: isolation of beta-catenin/plakoglobin-deficient F9 cells. Cell Struct Funct. 2005;30(2):25–34. doi: 10.1247/csf.30.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene FL, Sobin LH. A worldwide approach to the TNM staging system: collaborative efforts of the AJCC and UICC. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99(5):269–272. doi: 10.1002/jso.21237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mauri D, Pavlidis N, Ioannidis JP. Neoadjuvant versus adjuvant systemic treatment in breast cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(3):188–194. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mieog JS, van der Hage JA, van de Velde CJ. Preoperative chemotherapy for women with operable breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD005002. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005002.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buzdar AU, Valero V, Ibrahim NK, Francis D, Broglio KR, Theriault RL, Pusztai L, Green MC, Singletary SE, Hunt KK, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy with paclitaxel followed by 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy and concurrent trastuzumab in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive operable breast cancer: an update of the initial randomized study population and data of additional patients treated with the same regimen. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(1):228–233. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumors: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asano Y, Kashiwagi S, Onoda N, Kurata K, Morisaki T, Noda S, Takashima T, Ohsawa M, Kitagawa S, Hirakawa K. Clinical verification of sensitivity to preoperative chemotherapy in cases of androgen receptor-expressing positive breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(1):14–20. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kashiwagi S, Yashiro M, Takashima T, Aomatsu N, Kawajiri H, Ogawa Y, Onoda N, Ishikawa T, Wakasa K, Hirakawa K. C-kit expression as a prognostic molecular marker in patients with basal-like breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100(4):490–496. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umemura S, Kurosumi M, Moriya T, Oyama T, Arihiro K, Yamashita H, Umekita Y, Komoike Y, Shimizu C, Fukushima H, et al. Immunohistochemical evaluation for hormone receptors in breast cancer: a practically useful evaluation system and handling protocol. Breast Cancer. 2006;13(3):232–235. doi: 10.2325/jbcs.13.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, Dowsett M, McShane LM, Allison KH, Allred DC, Bartlett JM, Bilous M, Fitzgibbons P, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(2):241–256. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0953-SA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Thurlimann B, Senn HJ, Panel m: Strategies for subtypes--dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St. Gallen international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2011. Ann Oncol 2011, 22(8):1736-1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Sivrikoz ON, Doganay L, Sivrikoz UK, Karaarslan S, Sanal SM. Distribution of CXCR4 and gamma-catenin expression pattern in breast cancer subtypes and their relationship to axillary nodal involvement. Pol J Pathol. 2013;64(4):253–259. doi: 10.5114/pjp.2013.39333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kashiwagi S, Yashiro M, Takashima T, Aomatsu N, Ikeda K, Ogawa Y, Ishikawa T, Hirakawa K. Advantages of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with triple-negative breast cancer at stage II: usefulness of prognostic markers E-cadherin and Ki67. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(6):R122. doi: 10.1186/bcr3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kashiwagi S, Yashiro M, Takashima T, Nomura S, Noda S, Kawajiri H, Ishikawa T, Wakasa K, Hirakawa K. Significance of E-cadherin expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(2):249–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathot L, Stenninger J. Behavior of seeds and soil in the mechanism of metastasis: a deeper understanding. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(4):626–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aktary Z, Pasdar M. Plakoglobin: role in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:189521. doi: 10.1155/2012/189521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gosavi P, Kundu ST, Khapare N, Sehgal L, Karkhanis MS, Dalal SN. E-cadherin and plakoglobin recruit plakophilin3 to the cell border to initiate desmosome assembly. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68(8):1439–1454. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0531-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kundu ST, Gosavi P, Khapare N, Patel R, Hosing AS, Maru GB, Ingle A, Decaprio JA, Dalal SN. Plakophilin3 downregulation leads to a decrease in cell adhesion and promotes metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(10):2303–2314. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khramtsov AI, Khramtsova GF, Tretiakova M, Huo D, Olopade OI, Goss KH. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway activation is enriched in basal-like breast cancers and predicts poor outcome. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(6):2911–2920. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geyer FC, Lacroix-Triki M, Savage K, Arnedos M, Lambros MB, MacKay A, Natrajan R. Reis-Filho JS: beta-Catenin pathway activation in breast cancer is associated with triple-negative phenotype but not with CTNNB1 mutation. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(2):209–231. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer KR, Durrans A, Lee S, Sheng J, Li F, Wong ST, Choi H, El Rayes T, Ryu S, Troeger J, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is not required for lung metastasis but contributes to chemoresistance. Nature. 2015;527(7579):472–476. doi: 10.1038/nature15748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh A, Settleman J. EMT, cancer stem cells and drug resistance: an emerging axis of evil in the war on cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29(34):4741–4751. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hakimelahi S, Parker HR, Gilchrist AJ, Barry M, Li Z, Bleackley RC, Pasdar M. Plakoglobin regulates the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(15):10905–10911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kolligs FT, Kolligs B, Hajra KM, Hu G, Tani M, Cho KR. Fearon ER: gamma-catenin is regulated by the APC tumor suppressor and its oncogenic activity is distinct from that of beta-catenin. Genes Dev. 2000;14(11):1319–1331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiina H, Breault JE, Basset WW, Enokida H, Urakami S, Li LC, Okino ST, Deguchi M, Kaneuchi M, Terashima M, et al. Functional loss of the gamma-catenin gene through epigenetic and genetic pathways in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(6):2130–2138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Immunohistochemical determination of β-catenin was observed at cell–cell boundaries of breast cancer cells. β-catenin expression was considered high if cells were ≥30% (A), and low when cells were <30% (B) (400×). (TIFF 505 kb)

Clinical response rate and pathological response rate to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. (DOCX 11 kb)

Univariate and multivariate analysis with respect to overall survival in 121 patients with breast cancer. (DOCX 14 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.