SUMMARY

Objective

Robotic-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy (RAMIE) is an emerging, complex operation with limited reports detailing morbidity, mortality, and requirements for attaining proficiency. Our objective was to develop a standardized RAMIE technique, evaluate procedure safety, and assess outcomes using a dedicated operative team and two surgeon approach.

Methods

We conducted a study of sequential patients undergoing RAMIE from January 25, 2011, May 5, 2014. Intermedian demographics and perioperative data were compared between sequential halves of the experience using Wilcoxon rank sum test and Fischer’s exact test. Median operative time was tracked over successive 15-patient cohorts.

Results

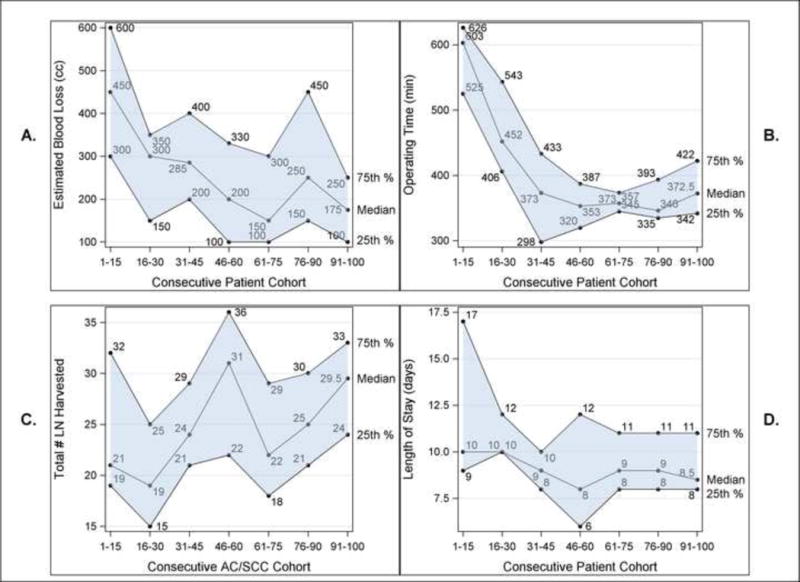

100 of 313 esophageal resections performed at our institution underwent RAMIE during the study period. A dedicated team including two attending surgeons, and uniform anesthesia and OR staff was established. Patient demographics and outcomes are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, gender, histology, stage, induction therapy, or risk class between the two halves of the study. Estimated blood loss, conversions, operative times, and overall complications significantly decreased. The median resected lymph nodes increased, but was not statistically significant. Median operative time decreased to approximately 370 minutes between the 30th and the 45th cases (Figure 1). There were no emergent intra-operative complications and the anastomotic leak rate was 6% (6/100). 30-day mortality was 0% (0/100) and 90-day mortality was 1% (1/100).

Conclusions

Excellent perioperative and short-term patient outcomes with minimal mortality can be achieved using a standardized RAMIE procedure and dedicated team approach. The structured process described may serve as a model to maximize patient safety during development and assessment of complex novel procedures.

Keywords: Esophageal Cancer, Surgery Outcomes, Robotic Esophagectomy, Esophagectomy, Learning Curve

INTRODUCTION

Minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) is an alternative to open esophagectomy with equivalent oncologic outcomes and mortality rates, and potentially improved morbidity and quality of life indicators [1–3]. The learning curve for these operations is significant and the procedures technically demanding, requiring advanced surgical minimally invasive expertise.

Reports of robotic assisted approaches to esophagectomy are emerging, with the putative benefit over standard approaches of improving the primary surgeon’s control over the conduct of the operation. Published experience with robotic assisted MIE (RAMIE) is limited but growing, although reported approaches are quite varied and outcomes difficult to compare between studies [4, 5]. Assessment of the learning curve for these operations is likewise difficult to interpret from study to study given the variation between techniques described, including totally minimally invasive versus hybrid approaches involving either laparoscopy, thoracoscopy, or both[6–9].

A complete robotic assisted laparoscopic and thoracoscopic RAMIE procedure has been under development at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, a high-volume esophageal cancer tertiary referral center, as part of a formal prospective clinical program with a primary emphasis on maximizing patient safety during the evaluation of new technology towards established operations. Our early technical approach and experience with the procedure in 21 patients has been previously reported, with a focus on pitfalls, complications, and cautions encountered during initial development of the program[10]. The objective of the current study is to report our model of procedure development resulting in ongoing refinement and standardization of the procedure over time while maintaining a primary focus on patient safety.

METHODS

An academic clinical plan to develop a standardized RAMIE approach was initiated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center with the goal of assessing the incorporation of new technology (robotics) towards a standard operation (esophagectomy). A central mandate of the program design was maximization of patient safety throughout the process, with key programmatic elements towards that end outlined below, while developing a uniform method to the conduct of the operation. An Institutional Review Board waiver was granted. Study elements were designed to perform concurrent and timely safety monitoring and data acquisition.

Pre-program cadaveric study

An initial, single cadaveric feasibility operation, or “dry-run”, was performed by the study surgeons and senor consulting surgeon prior to initiation of clinical cases with the purpose of planning gross mechanics of the operation (i.e. port placement, robot and table positioning, anesthesia positioning, conduct of operation, etc.) and to identify potential inherent pitfalls early in the course of development. While a critical first step to promote a smooth transition to the clinical setting, no major limitations were identified from this part of the study.

Two attending approach

After case six, all RAMIE procedures were performed by a consistent “console” and “bedside” two attending team (I.S.S. and N.P.R.), with significant combined experience in advanced minimally invasive techniques, including formal advanced fellowship training in minimally invasive esophagectomy, and robotic assisted procedures. The console and bedside attending roles were alternated after the first 50 cases (“training” phase). Additional dedicated staff including a limited set of anesthesiologists, operating room scrub technicians, and circulating staff routinely involved with the thoracic service and familiar with the operation.

Senior partner as “expert consultant”

The most experienced senior esophageal surgeon in our group (M.S.B.) graciously served as a formal procedural consultant and advisor throughout inception and development, with direct observation of cases, technical critique, and recommendations for procedural improvement.

Training and Teaching Phases

During the first 50 case initial development and Training phase, the vast majority of every RAMIE procedure was performed exclusively by the attending team with consistent “console” (I.S.S.) and “bedside” (N.P.R.) roles. Program trainees (residents and fellows) second-assisted at the second robotic console and/or bedside. During the second 50 case Teaching phase, greater emphasis was placed on graded teaching of the procedure, with supervised performance of discrete portions of each operation by the resident or fellow at the robotic console. During this phase, the two attending surgeons alternated their roles between the console and the bedside assist with each successive case.

Immediate case critique and refinement of technique

All cases underwent immediate post-case critical review by the study attending surgeons to identify operative challenges and pitfalls. All post-operative complications were identified and underwent immediate formal review by the study attendings, including the senior consulting attending, to identify clear or putative root causes. All technical complications included discussion with senior partners and video review of key elements of the operation to identify known or otherwise potentially unrecognized technical errors. Potential critical and non-critical procedural refinements were identified, planned, and incorporated with the subsequent case.

Program termination points

A pre-determined termination point of 50 cases was set if less than equivalent outcomes or safety indices to accepted service norms for esophagectomy were identified. An immediate program termination point was set if solutions to observed highly morbid technical pitfalls specific to RAMIE could not be identified.

Set requirements for conversion

Mandated conversion points from RAMIE to standard minimally invasive or open surgery included anticipated excessive operating time, failure to significantly progress, and/or intraoperative complications.

Our RAMIE method has previously been described, including robotic assisted laparoscopy and thoracoscopy with gastric mobilization, pyloroplasty, gastric conduit formation, esophageal mobilization and creation of a circular stapled thoracic anastomosis (Ivor Lewis) or hand-sewn neck anastomosis (McKeown)[4].

All consecutive patients during the study period undergoing RAMIE were included. Patients deemed surgical candidates for esophagectomy were selected for the RAMIE procedure by virtue of presenting to the two study attending surgeons. All patients had biopsy confirmed esophageal cancer by esophagogastroscopy and underwent standard pre-operative evaluation including computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and endoscopic ultrasound. Patient demographics, operative times and peri-operative outcomes were recorded. Statistical comparisons were performed between the first and second half of the experience using the Wilcoxon rank sum test and Fisher’s exact test. Trends in median operative time, estimated blood loss, length of stay, and lymph node count were assessed between successive 15-patient cohorts using median and interquartile (25th–75th percentile) plots. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC USA).

RESULTS

Patients Demographics

Patient demographics and study outcomes are outlined in Table 1. 100 of 313 esophageal resections performed at our institution underwent RAMIE and were evaluated during the study period from January 25, 2011 to May 5, 2014. 74% were male (median age 62 years, range: 37–83 years), 86% had adenocarcinomas, and 89% underwent an Ivor Lewis procedure with an intra-thoracic anastomosis. 73% received induction chemoradiation.

Table 1.

Overall and intermedian demographic characteristics and short-term outcomes in patients undergoing RAMIE.

| Variable | Overall | First half | Second half | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 100 | 50 | 50 | ||

| Age, years, median (range) | 62 (37–83) | 61 (37–83) | 63 (37–83) | 0.25 | |

| Male | 74 (74) | 39 (78) | 35 (70) | 0.49 | |

| Histology | 0.40 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 86 (86) | 41 (82) | 45 (90) | ||

| Squamous carcinoma | 10 (10) | 7 (14) | 3 (6) | ||

| Non-carcinoma | 4 (4) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | ||

| Induction chemoradiation | 73 (73) | 37 (74) | 36 (72) | >0.95 | |

| ASA risk class 3 & 4 | 85 (85) | 40 (80) | 45 (90) | 0.26 | |

| Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy | 89 (89) | 40 (80) | 49 (98) | ||

| Pathology stage | 0.79 | ||||

| Stage 0 (pCR) | 21 (21) | 12 (24) | 9 (18) | ||

| Stage 1 | 23 (23) | 10 (20) | 13 (26) | ||

| Stage 2 | 32 (32) | 17 (34) | 15 (30) | ||

| Stage 3 | 20 (20) | 9 (18) | 11 (22) | ||

| Complete resection (R0) | 90 (90) | 43 (86) | 47 (94) | 0.32 | |

| Lymph nodes, median (range) | 24 (10–56) | 23 (10–56) | 27 (15–45) | 0.08 | |

| Conversion | 0.004 | ||||

| To non-robotic MIS | 5 (5) | 5 (10) | 0 (0) | ||

| To open surgery | 10 (10) | 8 (16) | 2 (4) | ||

| Operative time, min, median (range) | 379 (275–807) | 447 (283–807) | 357 (275–524) | <0.001 | |

| Estimated blood loss, cc, median (range) | 250 (20–700) | 300 (50–650) | 200 (20–700) | 0.005 | |

| Length of stay, days, median (range) | 9 (5–70) | 10 (5–70) | 9 (5–54) | 0.12 | |

| Complications (CTCAE v 3.0) | 0.046 | ||||

| None | 458(48) | 20 (40) | 28 (56) | ||

| Grade 1–2 (minor) | 29 (29) | 20 (40) | 9 (18) | ||

| Grade 3–4 (major) | 22 (22) | 9 (18) | 13 (26) | ||

| Grade 5 (death) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | ||

| Anastomotic leak ≥ grade 2 | 6 (6) | 4 (8) | 2 (4) | 0.52 | |

Data are no. (%), unless otherwise noted; pCR – pathologic complete response; ASA – American Society of Anesthesia; CTCAE – Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

Intermedian comparison identified no differences in age, gender, tumor histology, induction therapy rates, ASA risk class, median length of stay, or pathology stage. 90% of patients had a complete resection (R0), with the remaining having microscopic positive margins (R1) identified on final pathology. Median lymph nodes resected increased between the groups (p=0.08), but were not statistically significant. Trends in median Estimated Blood Loss, Operative Time, Lymph Nodes Harvested, and Hospital Length of Stay over successive 15-patient cohorts are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

RAMIE trends over successive15-patient cohorts in median A.) Estimated blood loss, B.) Operating time, C.) Total lymph nodes harvested, and D.) Hospital length of stay.

Operative Time

Median operative times decreased significantly between the halves of the experience from 447 (range: 283–807) to 357 (range: 275–524) minutes (p<0.001), as determined by the operative record. When analyzed between cohorts of 15 patients, median operative times drop to approximately 370 minutes between 30–45 cases (Figure 1). In this series, operative times nadir at 45 cases with a median time for cases 40–45 of 298 minutes. With introduction of the Teaching phase with guidelines to keep the median time within reasonable limits, a modest but noticeable rise in median OR time is seen and quickly stabilizes over the remaining second half of the experience.

Conversions

Intermedian rates of conversion to non-robotic MIS or open procedures decreased significantly, with only 2 of 15 conversions occurring in the second half (p=0.004). There were no emergent conversions. Reasons for the 10 conversions to open surgery included questionable anastomotic integrity (2), poor visualization of greater gastric curve (2), positive proximal margin (1), inability to safely pass end anastomotic stapler in a patient with a greatly thickened gastric conduit (1), inability to safely advance conduit through into chest (1), dense fibrosis (1), repair of enterotomy (1), and for primary simple, single-suture repair and buttress with intercostal muscle flap of a small, non-thermal tear in left membranous mainstem bronchus in a patient with a grossly overinflated bronchial cuff (1) (patient recovered without incident or complications). The five conversions to laparoscopy included excessive poor visualization of the greater gastric curve (2), excessive operative time (2), and system failure of the robotic console (1).

Morbidity and Mortality

Complications were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Outcomes v. 3.0. 22 (22%) patients had Grade 3–4 (major) complications. Overall, complications decreased (p=0.046) over the experience. Rates of anastomotic leak greater or equal to grade 2 remained similar (p=0.52). Specific complications are summarized in Table 2. 30-day mortality was 0%, and 90-day mortality 1%, with one death due to gastric conduit-airway fistula repaired successfully, but with subsequent unrecoverable respiratory failure on post-operative day 70.

Table 2.

| Complications | Number |

|---|---|

| Grade 2 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 |

| Anastomotic leak | 4 |

| Anastomotic stricture | 3 |

| C. difficile colitis | 3 |

| Pleural effusion | 2 |

| UTI | 2 |

| Empyema | 2 |

| Anemia | 1 |

| Fever of unknown origin | 1 |

| Pneumonitis | 1 |

| Wound infection | 1 |

| Grade 3 | |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy | 4 |

| Vomiting/reflux | 2 |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 2 |

| Pneumonia | 2 |

| Anastomotic leak | 1 |

| Anastomotic leak/tracheoesophageal fistula | 1 |

| Respiratory failure | 1 |

| Postoperative hemorrhage | 1 |

| Chylothorax | 1 |

| C. difficile colitis | 1 |

| Wound infection | 1 |

| Pneumothorax | 1 |

| Septicemia | 1 |

| Pericardial effusion | 1 |

| Grade 4 | |

| Pulmonary embolus | 3 |

| Respiratory failure | 1 |

| Grade 5 | |

| Respiratory failure | 1 |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report our institutional experience with the RAMIE procedure as developed within a highly structured academic program focused on patient safety. Using an ongoing iterative process of procedure critique and development, several refinements to the RAMIE procedure were made and are detailed below.

Airway Dissection

As previously described, 2 patients developed conduit or anastomotic fistula complications involving the airway within one month of surgery[10]. While unclear if related specifically to the procedure, a third presented approximately three months after operation. Two of the fistulas were small (less than 5mm) and healed completely with temporary placement of covered esophageal stents. The third was successfully repaired, but the patient ultimately died from ongoing respiratory failure on post-operative day 70 and represents the only mortality in the series. It is important to note that these complications are not specific to the robotic approach, and represent a recognized manifestation of immediate or delayed injury to the airway during MIE with the use of thermal dissection devices, such as the ultrasonic shears. We have modified our technique during airway dissection to use of articulated bipolar energy instrumentation with minimal lateral thermal spread, and overall limitation of energy use during this portion of the operation. We have since seen no such complications due to thermal injury. Of note, one conversion in our late experience was due to a small 1mm direct injury to the membranous left-mainstem bronchus in the presence of a grossly over-inflated bronchial cuff. This occurred with non-energy dissection and was repaired with a simple suture and reinforced with an intercostal muscle flap. The patient’s post-operative course was without event.

Anastomosis

We simplified our method of securing the EEA stapler anvil into the proximal esophagus, with placement of the first purse-string suture prior to insertion of the anvil as opposed to after. While attention must be paid to avoid attempts at dilating the esophageal orifice while inadvertently grasping the suture in a fixed position, this technically less difficult modification also allows for more precise and unobstructed placement of the suture, thus avoiding a “rosebud” of excessive tissue around the anvil stem.

Intra-operative Fluorescence Imaging

As previously described, we incorporated the use of indocyanine green based Near Infrared Fluorescence Imaging (available on the current robotic platform) to better identify the right and left gastroepiploic arcades during dissection of the greater gastric curve[11]. This, and similar technologies, may increase the safety index of surgery by allowing clear visualization of otherwise obscured vital structures during dissection.

Replaced left hepatic artery

Three patients required sparing of a left hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery. This was accomplished readily and did not require conversion to open procedures. In the author’s opinion, the advanced technical capabilities of the robotic platform was a significant asset in these more complex scenarios. Of note, sparing of a replaced left hepatic artery is not routine in our practice, and it can often be sacrificed with little or no threat to hepatic viability. It is performed on the relatively rare occasion that the artery is deemed large enough, and in the presence of a substantial left hepatic lobe, to raise concern for significant liver ischemia. In this scenario, the replaced left hepatic artery is temporarily occluded with a small clip to assess perfusion/ischemia to the left liver prior to finalizing a decision to spare the artery.

Transhiatal Advancement of Conduit

After conversion to thoracotomy in one patient after inability to safely advance the conduit into the chest, our technique was modified from “pulling” the conduit directly towards the neck to “lifting” the gastric tube “up” towards the lateral chest, thus allowing easier and safer traverse of the sometimes bulky vascular arcade and omentum into the chest through the hiatus, and potentially avoiding the need for “relaxing” incisions in the right crus. This technical modification was a direct result of technical advice from our senior consultant after review of procedure and video.

Limitations

There are several limitations of the study, including its relatively small numbers and potentially still maturing results. Also, conclusions regarding oncologic outcomes cannot be determined without further follow-up over time. It is also difficult to know how translatable the results are to other practices. The reported outcomes and process of procedure development at a single high volume center with extensive surgical and institutional experience in complex esophageal and minimally invasive procedures may represent a “best-case” scenario not easily reproducible in other practice settings. Development of formal training programs for complex procedures such as RAMIE may help achieve incorporation of such approaches into practice without recapitulation of know pitfalls and morbidity, such as airway injury. We caution that these approaches may best be performed in high volume centers with experience in complex esophageal surgery for cancer [12, 13].

Conclusions

Within a high volume esophageal cancer practice, the RAMIE procedure was feasible with excellent peri- and post-operative outcomes. We believe our reported results are due largely to adherence of key programmatic principles focused on evaluating and maintaining high safety and quality profiles throughout the process of procedure development. These include pre-execution planning, formal and ongoing procedure critique and refinement, a consistent experienced team, and defined procedure and program termination points. The current study outlines one potential paradigm for the evaluation and development of “disruptive” techniques and technologies, while maintaining a clear focus on the highest levels of patient safety.

Acknowledgments

NIH Core Grant P30 CA008748 helped fund the study.

Footnotes

Presented at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society for Minimally Invasive Cardiothoracic Surgery, June 3 – 6, 2015, Berlin, Germany.

Disclosures: Inderpal S. Sarkaria, MD, Nabil P. Rizk, MD, Rachel Grosser, BA, Debra Goldman, MA, David J. Finley, MD, Amanda Ghanie, BA, Camelia S. Sima, MD, Manjit S. Bains, MD, Prasad S. Adusumilli, MD, Valerie W. Rusch, MD, and David R. Jones, MD, declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Biere SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Maas KW, et al. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1887–1892. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60516-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luketich J, Pennathur A, Catalano PJ, et al. Results of a phase II multicenter study of minimally invasive esophagectomy (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E2202) J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2009;27:4516. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luketich JD, Pennathur A, Awais O, et al. Outcomes after minimally invasive esophagectomy: review of over 1000 patients. Ann Surg. 2012;256:95–103. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182590603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarkaria IS, Rizk NP. Robotic-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy: the Ivor Lewis approach. Thorac Surg Clin. 2014;24:211–222. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruurda JP, van der Sluis PC, van der Horst S, van Hilllegersberg R. Robot-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: A systematic review. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112:257–265. doi: 10.1002/jso.23922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez JM, Dimou F, Weber J, et al. Defining the Learning Curve for Robotic-assisted Esophagogastrectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1346–1351. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS, Hawn MT. Technical aspects and early results of robotic esophagectomy with chest anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weksler B, Sharma P, Moudgill N, et al. Robot-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy is equivalent to thoracoscopic minimally invasive esophagectomy. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:403–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SY, Kim DJ, Yu WS, Jung HS. Robot-assisted thoracoscopic esophagectomy with extensive mediastinal lymphadenectomy: experience with 114 consecutive patients with intrathoracic esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:326–332. doi: 10.1111/dote.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarkaria IS, Rizk NP, Finley DJ, et al. Combined thoracoscopic and laparoscopic robotic-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy using a four-arm platform: experience, technique and cautions during early procedure development. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43:e107–115. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkaria IS, Bains MS, Finley DJ, et al. Intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence imaging as an adjunct to robotic-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy. Innovations. 2014;9:391–393. doi: 10.1097/IMI.0000000000000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markar S, Gronnier C, Duhamel A, et al. Pattern of Postoperative Mortality After Esophageal Cancer Resection According to Center Volume: Results from a Large European Multicenter Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2615–2623. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reames BN, Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Hospital volume and operative mortality in the modern era. Ann Surg. 2014;260:244–251. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]