Abstract

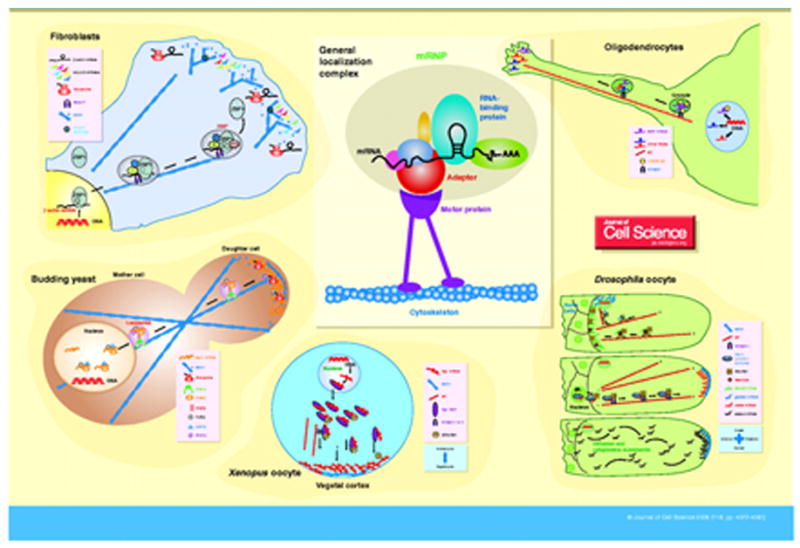

Messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules are transcribed in the nucleus and then undergo export into the cytoplasm, where they are translated to produce proteins. Some mRNA transcripts do not immediately undergo translation but, instead, are directed to specific areas for local translation or distribution. This produces an asymmetric distribution of cytoplasmic proteins, providing localized activities in polarized cells or developing embryos. Studies of the localization process in various eukaryotic systems have unearthed numerous nuclear RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) involved. We present here some representative examples from different organisms.

General features of mRNA localization systems

mRNA transcripts are coated by a variety of RBPs. Some of these are essential for mRNA localization and can be detected even when the mRNA is still nuclear. In many cases, specific sequence elements, ‘zipcodes’, in the untranslated region (UTR) form a secondary structure that serves as a docking site for the RBPs and thus promotes the localization process.

Localizing mRNAs are shuttled to specific areas of the cell or the organism along cytoskeletal elements such as microtubules or actin filaments. They seem to be actively translocated by motor proteins of the myosin, kinesin and dynein families. Although our knowledge of the components of the mRNP complexes is growing, the list we give here is by no means comprehensive and merely a general impression of the multitude of interactions necessary for the localization process.

Mammalian cells

mRNA localization in fibroblasts

β-actin mRNA localization has been identified in several mammalian systems (Lawrence and Singer, 1986). In migrating fibroblasts, β-actin mRNA is localized to the leading edge of the cells (Lawrence and Singer, 1986). This correlates with the elevated levels of β-actin protein required in lamellipodia, which depend on the rapid polymerization of actin for cell movement (Condeelis and Singer, 2005). Zipcode sequences (Kislauskis and Singer, 1992) immediately downstream of the stop codon (Kislauskis et al., 1993) recruit the zipcode-binding protein ZBP1 by interacting with its KH domains (Ross et al., 1997;Farina et al., 2003). ZBP1 and β-actin mRNA associate in the nucleus (Oleynikov and Singer, 2003) and travel in cytoplasmic granules to the leading edge. ZBP2, a predominantly nuclear protein, also binds the zipcode and affects localization (Gu et al., 2002). Translation is thought to be inhibited, perhaps by ZBP1, until the mRNA reaches the lamellipodia. β-actin-containing granules are transported on actin filaments (Sundell and Singer, 1991) and might anchor at specific sites through interactions with EF1α (Liu et al., 2002). The responsible motor is unidentified, although inhibition of myosin activity does disrupt the process (Latham et al., 2001).

The formation of the branched actin cytoskeleton at the protruding edge of migrating fibroblasts requires the Arp2/3 complex (Machesky et al., 1994). This seven-subunit complex (Machesky et al., 1997; Mullins et al., 1997; Welch et al., 1997), caps the slow-growing ends of actin filaments, while stabilizing the fast-growing polymerizing ends. The seven mRNAs that encode Arp2/3 subunits are all localized to the leading edge of fibroblasts, which supports the idea that localized translation of functionally-related mRNAs is coupled to the assembly of complexes (Mingle et al., 2005).

mRNA localization in the neuronal system

mRNA localization mechanisms also allow local translation in the extremities (dendrites and axons) of cells from the neuronal system (Job and Eberwine, 2001). The mRNAs typically travel from the cell body in granules that contain several copies of the mRNA or several types of mRNA. Myelin basic protein (MBP) mRNAs, for example, are targeted to the myelin membranes of oligodendrocyte cell processes (Ainger et al., 1993). They probably associate with microtubules through a kinesin motor (Carson et al., 1997) and are bound by the RNA-binding protein hnRNP A2 (Hoek et al., 1998). Other examples are localization of CamKIIα mRNA by kinesin in hippocampal dendrites (Kanai et al., 2004; Rook et al., 2000) and translocation of tau mRNA on microtubules in axons, in which a relative of ZBP1, IMP-1, is involved (Atlas et al., 2004). β-actin mRNA is localized to neuronal growth cones and hippocampal dendrites through similar association with ZBP1 (Bassell et al., 1998; Eom et al., 2003). Long-distance translocation occurs along microtubules (Zhang et al., 2001), using an unidentified motor protein, probably kinesin (our unpublished data). Since the distance between dendrites or axons and the cell nucleus can be extremely large, this localization mechanism allows rapid translational responses that are independent of the ongoing transcription in the nucleus.

Budding yeast

Actin-based translocation of localized mRNAs also occurs in yeast (Darzacq et al., 2003; Gonsalvez et al., 2005). In budding yeast, many RNAs translocate from the mother cell into the budding daughter cell and concentrate at the bud tip (Shepard et al., 2003). One of the best studied examples is ASH1 mRNA (Long et al., 1997; Takizawa et al., 1997). Ash1p is a nuclear DNA-binding protein required for control of mating-type switching, and its asymmetric distribution causes the repression of HO endonuclease expression only in the daughter cell (Bobola et al., 1996; Sil and Herskowitz, 1996). ASH1 RNA is moved along actin filaments by a type V myosin, She1p/Myo4p, as part of an RNP complex termed the locasome (Beach et al., 1999; Bertrand et al., 1998). She2p is an RBP that binds to the ASH1 mRNA zipcode sequences in the nucleus, accompanies the mRNA in the cytoplasm (Bohl et al., 2000; Long et al., 2000; Niessing et al., 2004) and bridges the connection to the motor via She3p (Takizawa and Vale, 2000). Once at the bud tip, ASH1 mRNA might be anchored to cortical actin. The Puf6p protein interacts directly with the ASH1 mRNA and represses its translation during translocation to the daughter cell (Gu et al., 2004). Because Puf6p is nuclear, it might associate with ASH1 mRNA in the nucleus. Khd1p is a component of the locasome and localizes with ASH1 mRNA at the bud tip and also inhibits translation (Irie et al., 2002). Loc1p is another nuclear protein that associates with ASH1 mRNA and might be important for mRNP assembly (Long et al., 2001).

Xenopus

Several mRNAs are localized to the different poles of Xenopus oocytes (Kloc and Etkin, 2005). The unequal distribution of specific mRNAs results in the development of unique daughter cells, providing a means by which germ cell lineages are defined and the primary axis for development is established. Vg1 protein is a member of the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily and has roles in mesoderm and endoderm development. Vg1 mRNA is localized to a tight region in the vegetal cortex of frog oocytes during oogenesis (Melton, 1987). It harbors a zipcode (Mowry and Melton, 1992) that interacts with the protein Vg1-RBP/Vera (Deshler et al., 1998; Havin et al., 1998; Schwartz et al., 1992) through its KH domains (Git and Standart, 2002) and mediates association with microtubules (Elisha et al., 1995).Xenopus Vg1-RBP/Vera is highly related to mammalian ZBP1, and both are part of a family of closely related RBPs involved in RNA regulation (Yisraeli, 2005). Movement of Vg1 mRNA along microtubules (Yisraeli et al., 1990) could involve kinesin motors and the Staufen RBP (see below) (Allison et al., 2004;Betley et al., 2004; Yoon and Mowry, 2004). Interestingly, during these stages of Xenopus development most of the microtubules have their plus ends pointed towards the nucleus (Pfeiffer and Gard, 1999), and therefore it remains unclear how mRNAs localize in the opposite direction (Kloc and Etkin, 2005). Other transport mechanisms might exist – for instance, the association of Vg1 mRNA with ER-membrane vesicles (Deshler et al., 1997). Several other proteins have also been implicated as being part of the zipcode-binding localization complex: VgRBP60/PTB/hnRNP I (Cote et al., 1999); Prrp (Zhao et al., 2001); xStau (Yoon and Mowry, 2004); VgRBP71 (Kroll et al., 2002); 40LoVe (Czaplinski et al., 2005). Some of these, like ZBP2, are predominantly nuclear, which suggests a nuclear connection for cytoplasmic localization (Farina and Singer, 2002; Kress et al., 2004).

Drosophila

Localization of nanos, oskar, bicoid and gurken mRNAs during oogenesis

Localized translation is controlled spatially and temporally in specified areas in Drosophila oocytes and embryos. In the oocyte, nanos mRNA is localized to the posterior during development, and Nanos protein is required for the formation of the anterior-posterior body axis (Gavis and Lehmann, 1992;Tautz, 1988). Most nanos mRNA does not localize and is translationally repressed (Bergsten and Gavis, 1999) or degraded (Bashirullah et al., 1999). Posterior-localized nanos mRNA, however, is stable and translated. The localization of nanos mRNA occurs late in oogenesis when the nurse cells release their cytoplasmic contents and the mRNA moves into the oocyte. In contrast to other systems, nanos mRNA seems to move by diffusion, enhanced by microtubule-dependent cytoplasmic streaming, to the posterior region, where it is anchored to the actin cytoskeleton (Forrest and Gavis, 2003). nanos mRNA contains several regions in its 3′ UTR that are required for its localization (Dahanukar and Wharton, 1996; Gavis et al., 1996). One stem-loop element is bound by the Smaug protein (Smg), which acts in translational repression of Nanos (Crucs et al., 2000; Dahanukar et al., 1999; Smibert et al., 1996).

The localization of nanos mRNA requires the Oskar protein (Ephrussi et al., 1991). oskar mRNA is also localized to the posterior of the embryo and is one of the first molecules to be recruited – probably by a kinesin-I-based mechanism (Brendza et al., 2000). Although oskar mRNA has a 3′ UTR that is required for its localization (Kim-Ha et al., 1993), protein components of the exon-junction-complex (EJC) accompany the mRNA from the nucleus to its destination (Hachet and Ephrussi, 2001; Mohr et al., 2001), and the splicing reaction itself may be necessary for oskar mRNA localization (Hachet and Ephrussi, 2004). Several other trans-acting factors required have been identified. Staufen, for example, is an RBP that colocalizes with oskar mRNA at the posterior pole and is required for its localization and translation (Micklem et al., 2000; Rongo et al., 1995; St Johnston et al., 1991). Staufen is necessary for the localization of another Drosophila mRNA, bicoid, to the anterior pole during late stages of oogenesis (St Johnston et al., 1991), interacting with stem-loop structures in the 3′ UTR of this mRNA (Ferrandon et al., 1994). Bicoid is a transcription factor that diffuses from the anterior pole to form a gradient throughout the embryo. During earlier stages of oogenesis, bicoid localization depends on the Exuperantia protein (St Johnston et al., 1989) and then on Swallow protein for anterior anchoring (Stephenson et al., 1988). bicoid mRNA is transcribed in the oocyte nurse cells and then translocates into the oocyte, where it moves along microtubules (Cha et al., 2001), connecting through Swallow to a dynein motor (Duncan and Warrior, 2002; Januschke et al., 2002; Schnorrer et al., 2000).

Dynein also moves gurken mRNA along microtubules to the anterior; there it changes direction moving towards the oocyte nucleus, where it localizes (MacDougall et al., 2003). The localization of Gurken, the Drosophila homologue of transforming growth factor α (TGFα), is important for the establishment of both the anteroposterior and the dorso-ventral axes.

Localization in the embryo

Later stages of Drosophila development also require RNA localization events, which occur after the setting of anteriorposterior protein gradients in the oocyte. In the blastoderm embryo, gap genes are located in broad segments along the anterior-posterior axis, yielding local mRNA expression and protein translation.

The differences in concentrations of gap gene products such as Krüppel, Hunchback and Giant give rise to embryo segmentation in conjunction with localized expression of pair-rule genes. The pair-rule genes ftz, hairy and runt are expressed in a segmental seven-stripe pattern in the syncytial embryo (Davis and Ish-Horowicz, 1991). When transcribed, these transcripts diffuse into the cytoplasm in all directions and later localize to their correct positions in RNA particles, moving on microtubules by dynein motors (Wilkie and Davis, 2001). Two other proteins, Bicaudal-D (BicD) and Egalitarian (Egl), are important for dynein-mediated transport of localized mRNAs both in the oocyte and the embryo (Bullock and Ish-Horowicz, 2001). Egl binds to dynein light chain and to BicD and might bridge the connection between the motor and RNA cargo (Mach and Lehmann, 1997; Navarro et al., 2004).

Outlook

The list of mRNAs known to be localized now stands at well over 100. In neurons alone, the number is probably even higher. Many questions remain: what are the complex motor systems that transport mRNAs and how do they ‘choose’ their respective cargos and cytoskeletal tracks, do mRNAs commit to localization in the nucleus, which proteins cooperate in the assembly of localization granules, which mRNAs are co-transported in the same granules and how is the translation of these mRNAs regulated? The combination of molecular and protein strategies in conjunction with live-cell imaging techniques should bring us closer to understanding the different mechanisms of mRNA localization and how they evolved in various species. For instance, following single, localizing mRNAs indicates that events involving RNA diffusion, assembly of motor complexes and interaction with cytoskeletal filaments are all probabilistic. Having a zipcode increases the probability of each of those events that lead to localization (Fusco et al., 2003). Further analysis of these factors at the molecular level will be an important next step in decoding the localization process.

Figure 1.

RNA Localization

References

- Ainger K, Avossa D, Morgan F, Hill SJ, Barry C, Barbarese E, Carson JH. Transport and localization of exogenous myelin basic protein mRNA microinjected into oligodendrocytes. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:431–441. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.2.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison R, Czaplinski K, Git A, Adegbenro E, Stennard F, Houliston E, Standart N. Two distinct Staufen isoforms in Xenopus are vegetally localized during oogenesis. RNA. 2004;10:1751–1763. doi: 10.1261/rna.7450204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlas R, Behar L, Elliott E, Ginzburg I. The insulin-like growth factor mRNA binding-protein IMP-1 and the Ras-regulatory protein G3BP associate with tau mRNA and HuD protein in differentiated P19 neuronal cells. J Neurochem. 2004;89:613–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashirullah A, Halsell SR, Cooperstock RL, Kloc M, Karaiskakis A, Fisher WW, Fu W, Hamilton JK, Etkin LD, Lipshitz HD. Joint action of two RNA degradation pathways controls the timing of maternal transcript elimination at the midblastula transition in Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J. 1999;18:2610–2620. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell GJ, Zhang H, Byrd AL, Femino AM, Singer RH, Taneja KL, Lifshitz LM, Herman IM, Kosik KS. Sorting of beta-actin mRNA and protein to neurites and growth cones in culture. J Neurosci. 1998;18:251–265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00251.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach DL, Salmon ED, Bloom K. Localization and anchoring of mRNA in budding yeast. Curr Biol. 1999;9:569–578. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten SE, Gavis ER. Role for mRNA localization in translational activation but not spatial restriction of nanos RNA. Development. 1999;126:659–669. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand E, Chartrand P, Schaefer M, Shenoy SM, Singer RH, Long RM. Localization of ASH1 mRNA particles in living yeast. Mol Cell. 1998;2:437–445. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betley JN, Heinrich B, Vernos I, Sardet C, Prodon F, Deshler JO. Kinesin II mediates Vg1 mRNA transport in Xenopus oocytes. Curr Biol. 2004;14:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobola N, Jansen RP, Shin TH, Nasmyth K. Asymmetric accumulation of Ash1p in postanaphase nuclei depends on a myosin and restricts yeast mating-type switching to mother cells. Cell. 1996;84:699–709. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohl F, Kruse C, Frank A, Ferring D, Jansen RP. She2p, a novel RNA-binding protein tethers ASH1 mRNA to the Myo4p myosin motor via She3p. EMBO J. 2000;19:5514–5524. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendza RP, Serbus LR, Duffy JB, Saxton WM. A function for kinesin I in the posterior transport of oskar mRNA and Staufen protein. Science. 2000;289:2120–2122. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock SL, Ish-Horowicz D. Conserved signals and machinery for RNA transport in Drosophila oogenesis and embryogenesis. Nature. 2001;414:611–616. doi: 10.1038/414611a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson JH, Worboys K, Ainger K, Barbarese E. Translocation of myelin basic protein mRNA in oligodendrocytes requires microtubules and kinesin. Cell Motil Cytoskel. 1997;38:318–328. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1997)38:4<318::AID-CM2>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha BJ, Koppetsch BS, Theurkauf WE. In vivo analysis of Drosophila bicoid mRNA localization reveals a novel microtubule-dependent axis specification pathway. Cell. 2001;106:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00419-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condeelis J, Singer RH. How and why does beta-actin mRNA target? Biol Cell. 2005;97:97–110. doi: 10.1042/BC20040063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote CA, Gautreau D, Denegre JM, Kress TL, Terry NA, Mowry KL. A Xenopus protein related to hnRNP I has a role in cytoplasmic RNA localization. Mol Cell. 1999;4:431–437. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crucs S, Chatterjee S, Gavis ER. Overlapping but distinct RNA elements control repression and activation of nanos translation. Mol Cell. 2000;5:457–467. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80440-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaplinski K, Kocher T, Schelder M, Segref A, Wilm M, Mattaj IW. Identification of 40LoVe, a Xenopus hnRNP D family protein involved in localizing a TGF-beta-related mRNA during oogenesis. Dev Cell. 2005;8:505–515. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahanukar A, Wharton RP. The Nanos gradient in Drosophila embryos is generated by translational regulation. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2610–2620. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahanukar A, Walker JA, Wharton RP. Smaug, a novel RNA-binding protein that operates a translational switch in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 1999;4:209–218. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80368-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzacq X, Powrie E, Gu W, Singer RH, Zenklusen D. RNA asymmetric distribution and daughter/mother differentiation in yeast. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis I, Ish-Horowicz D. Apical localization of pair-rule transcripts requires 3′ sequences and limits protein diffusion in the Drosophila blastoderm embryo. Cell. 1991;67:927–940. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshler JO, Highett MI, Schnapp BJ. Localization of Xenopus Vg1 mRNA by Vera protein and the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 1997;276:1128–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshler JO, Highett MI, Abramson T, Schnapp BJ. A highly conserved RNA-binding protein for cytoplasmic mRNA localization in vertebrates. Curr Biol. 1998;8:489–496. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JE, Warrior R. The cytoplasmic dynein and kinesin motors have interdependent roles in patterning the Drosophila oocyte. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1982–1991. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elisha Z, Havin L, Ringel I, Yisraeli JK. Vg1 RNA binding protein mediates the association of Vg1 RNA with microtubules in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1995;14:5109–5114. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eom T, Antar LN, Singer RH, Bassell GJ. Localization of a beta-actin messenger ribonucleoprotein complex with zipcode-binding protein modulates the density of dendritic filopodia and filopodial synapses. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10433–10444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10433.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ephrussi A, Dickinson LK, Lehmann R. Oskar organizes the germ plasm and directs localization of the posterior determinant nanos. Cell. 1991;66:37–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90137-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina KL, Singer RH. The nuclear connection in RNA transport and localization. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:466–472. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina KL, Huttelmaier S, Musunuru K, Darnell R, Singer RH. Two ZBP1 KH domains facilitate beta-actin mRNA localization, granule formation, and cytoskeletal attachment. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:77–87. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandon D, Elphick L, Nusslein-Volhard C, St Johnston D. Staufen protein associates with the 3′UTR of bicoid mRNA to form particles that move in a microtubule-dependent manner. Cell. 1994;79:1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest KM, Gavis ER. Live imaging of endogenous RNA reveals a diffusion and entrapment mechanism for nanos mRNA localization in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1159–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco D, Accornero N, Lavoie B, Shenoy SM, Blanchard JM, Singer RH, Bertrand E. Single mRNA Molecules demonstrate probabilistic movement in living mammalian cells. Curr Biol. 2003;13:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01436-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavis ER, Lehmann R. Localization of nanos RNA controls embryonic polarity. Cell. 1992;71:301–313. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90358-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavis ER, Curtis D, Lehmann R. Identification of cis-acting sequences that control nanos RNA localization. Dev Biol. 1996;176:36–50. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.9996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Git A, Standart N. The KH domains of Xenopus Vg1RBP mediate RNA binding and self-association. RNA. 2002;8:1319–1333. doi: 10.1017/s135583820202705x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalvez GB, Urbinati CR, Long RM. RNA localization in yeast: moving towards a mechanism. Biol Cell. 2005;97:75–86. doi: 10.1042/BC20040066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Pan F, Zhang H, Bassell GJ, Singer RH. A predominantly nuclear protein affecting cytoplasmic localization of beta-actin mRNA in fibroblasts and neurons. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:41–51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Deng Y, Zenklusen D, Singer RH. A new yeast PUF family protein, Puf6p, represses ASH1 mRNA translation and is required for its localization. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1452–1465. doi: 10.1101/gad.1189004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachet O, Ephrussi A. Drosophila Y14 shuttles to the posterior of the oocyte and is required for oskar mRNA transport. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1666–1674. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00508-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachet O, Ephrussi A. Splicing of oskar RNA in the nucleus is coupled to its cytoplasmic localization. Nature. 2004;428:959–963. doi: 10.1038/nature02521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havin L, Git A, Elisha Z, Oberman F, Yaniv K, Schwartz SP, Standart N, Yisraeli JK. RNA-binding protein conserved in both microtubule- and microfilament-based RNA localization. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1593–1598. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek KS, Kidd GJ, Carson JH, Smith R. hnRNP A2 selectively binds the cytoplasmic transport sequence of myelin basic protein mRNA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7021–7029. doi: 10.1021/bi9800247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YS, Richter JD. Regulation of local mRNA translation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie K, Tadauchi T, Takizawa PA, Vale RD, Matsumoto K, Herskowitz I. The Khd1 protein, which has three KH RNA-binding motifs, is required for proper localization of ASH1 mRNA in yeast. EMBO J. 2002;21:1158–1167. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Januschke J, Gervais L, Dass S, Kaltschmidt JA, Lopez-Schier H, St Johnston D, Brand AH, Roth S, Guichet A. Polar transport in the Drosophila oocyte requires Dynein and Kinesin I cooperation. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1971–1981. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Job C, Eberwine J. Localization and translation of mRNA in dendrites and axons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:889–898. doi: 10.1038/35104069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai Y, Dohmae N, Hirokawa N. Kinesin transports RNA: isolation and characterization of an RNA-transporting granule. Neuron. 2004;43:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Ha J, Webster PJ, Smith JL, Macdonald PM. Multiple RNA regulatory elements mediate distinct steps in localization of oskar mRNA. Development. 1993;119:169–178. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kislauskis EH, Singer RH. Determinants of mRNA localization. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992;4:975–978. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90128-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kislauskis EH, Li Z, Singer RH, Taneja KL. Isoform-specific 3′-untranslated sequences sort alpha-cardiac and beta-cytoplasmic actin messenger RNAs to different cytoplasmic compartments. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:165–172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloc M, Etkin LD. RNA localization mechanisms in oocytes. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:269–282. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress TL, Yoon YJ, Mowry KL. Nuclear RNP complex assembly initiates cytoplasmic RNA localization. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:203–211. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll TT, Zhao WM, Jiang C, Huber PW. A homolog of FBP2/KSRP binds to localized mRNAs in Xenopus oocytes. Development. 2002;129:5609–5619. doi: 10.1242/dev.00160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham VM, Yu EH, Tullio AN, Adelstein RS, Singer RH. A Rho-dependent signaling pathway operating through myosin localizes beta-actin mRNA in fibroblasts. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1010–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JB, Singer RH. Intracellular localization of messenger RNAs for cytoskeletal proteins. Cell. 1986;45:407–415. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Grant WM, Persky D, Latham VM, Jr, Singer RH, Condeelis J. Interactions of elongation factor 1alpha with F-actin and beta-actin mRNA: implications for anchoring mRNA in cell protrusions. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:579–592. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-03-0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long RM, Singer RH, Meng X, Gonzalez I, Nasmyth K, Jansen RP. Mating type switching in yeast controlled by asymmetric localization of ASH1 mRNA. Science. 1997;277:383–387. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long RM, Gu W, Lorimer E, Singer RH, Chartrand P. She2p is a novel RNA-binding protein that recruits the Myo4p-She3p complex to ASH1 mRNA. EMBO J. 2000;19:6592–6601. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long RM, Gu W, Meng X, Gonsalvez G, Singer RH, Chartrand P. An exclusively nuclear RNA-binding protein affects asymmetric localization of ASH1 mRNA and Ash1p in yeast. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:307–318. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall N, Clark A, MacDougall E, Davis I. Drosophila gurken (TGFalpha) mRNA localizes as particles that move within the oocyte in two dynein-dependent steps. Dev Cell. 2003;4:307–319. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mach JM, Lehmann R. An Egalitarian-BicaudalD complex is essential for oocyte specification and axis determination in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1997;11:423–435. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machesky LM, Atkinson SJ, Ampe C, Vandekerckhove J, Pollard TD. Purification of a cortical complex containing two unconventional actins from Acanthamoeba by affinity chromatography on profilin-agarose. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:107–115. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machesky LM, Reeves E, Wientjes F, Mattheyse FJ, Grogan A, Totty NF, Burlingame AL, Hsuan JJ, Segal AW. Mammalian actin-related protein 2/3 complex localizes to regions of lamellipodial protrusion and is composed of evolutionarily conserved proteins. Biochem J. 1997;328:105–112. doi: 10.1042/bj3280105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton DA. Translocation of a localized maternal mRNA to the vegetal pole of Xenopus oocytes. Nature. 1987;328:80–82. doi: 10.1038/328080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micklem DR, Adams J, Grunert S, St Johnston D. Distinct roles of two conserved Staufen domains in oskar mRNA localization and translation. EMBO J. 2000;19:1366–1377. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingle LA, Okuhama NN, Shi J, Singer RH, Condeelis J, Liu G. Localization of all seven messenger RNAs for the actin-polymerization nucleator Arp2/3 complex in the protrusions of fibroblasts. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2425–2433. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr SE, Dillon ST, Boswell RE. The RNA-binding protein Tsunagi interacts with Mago Nashi to establish polarity and localize oskar mRNA during Drosophila oogenesis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2886–2899. doi: 10.1101/gad.927001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowry KL, Melton DA. Vegetal messenger RNA localization directed by a 340-nt RNA sequence element in Xenopus oocytes. Science. 1992;255:991–994. doi: 10.1126/science.1546297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins RD, Stafford WF, Pollard TD. Structure, subunit topology, and actin-binding activity of the Arp2/3 complex from Acanthamoeba. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:331–343. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.2.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro C, Puthalakath H, Adams JM, Strasser A, Lehmann R. Egalitarian binds dynein light chain to establish oocyte polarity and maintain oocyte fate. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:427–335. doi: 10.1038/ncb1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessing D, Huttelmaier S, Zenklusen D, Singer RH, Burley SK. She2p is a novel RNA binding protein with a basic helical hairpin motif. Cell. 2004;119:491–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleynikov Y, Singer RH. Real-time visualization of ZBP1 association with beta-actin mRNA during transcription and localization. Curr Biol. 2003;13:199–207. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00044-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer DC, Gard DL. Microtubules in Xenopus oocytes are oriented with their minus-ends towards the cortex. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1999;44:34–43. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(199909)44:1<34::AID-CM3>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rongo C, Gavis ER, Lehmann R. Localization of oskar RNA regulates oskar translation and requires Oskar protein. Development. 1995;121:2737–2746. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook MS, Lu M, Kosik KS. CaMKIIalpha 3′ untranslated region-directed mRNA translocation in living neurons: visualization by GFP linkage. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6385–6893. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06385.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross AF, Oleynikov Y, Kislauskis EH, Taneja KL, Singer RH. Characterization of a beta-actin mRNA zipcode-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2158–2165. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnorrer F, Bohmann K, Nusslein-Volhard C. The molecular motor dynein is involved in targeting swallow and bicoid RNA to the anterior pole of Drosophila oocytes. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:185–190. doi: 10.1038/35008601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SP, Aisenthal L, Elisha Z, Oberman F, Yisraeli JK. A 69-kDa RNA-binding protein from Xenopus oocytes recognizes a common motif in two vegetally localized maternal mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11895–11899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard KA, Gerber AP, Jambhekar A, Takizawa PA, Brown PO, Herschlag D, DeRisi JL, Vale RD. Widespread cytoplasmic mRNA transport in yeast: identification of 22 bud-localized transcripts using DNA microarray analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11429–11434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2033246100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sil A, Herskowitz I. Identification of asymmetrically localized determinant, Ash1p, required for lineage-specific transcription of the yeast HO gene. Cell. 1996;84:711–722. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smibert CA, Wilson JE, Kerr K, Macdonald PM. smaug protein represses translation of unlocalized nanos mRNA in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2600–2609. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D, Driever W, Berleth T, Richstein S, Nusslein-Volhard C. Multiple steps in the localization of bicoid RNA to the anterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Development. 1989;107:13–19. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.Supplement.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D, Beuchle D, Nusslein-Volhard C. Staufen, a gene required to localize maternal RNAs in the Drosophila egg. Cell. 1991;66:51–63. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90138-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson EC, Chao YC, Fackenthal JD. Molecular analysis of the swallow gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1655–1665. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundell CL, Singer RH. Requirement of microfilaments in sorting of actin messenger RNA. Science. 1991;253:1275–1277. doi: 10.1126/science.1891715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa PA, Vale RD. The myosin motor, Myo4p, binds Ash1 mRNA via the adapter protein, She3p. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5273–5278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080585897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa PA, Sil A, Swedlow JR, Herskowitz I, Vale RD. Actin-dependent localization of an RNA encoding a cell-fate determinant in yeast. Nature. 1997;389:90–93. doi: 10.1038/38015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D. Regulation of the Drosophila segmentation gene hunchback by two maternal morphogenetic centres. Nature. 1988;332:281–284. doi: 10.1038/332281a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch MD, Iwamatsu A, Mitchison TJ. Actin polymerization is induced by Arp2/3 protein complex at the surface of Listeria monocytogenes. Nature. 1997;385:265–269. doi: 10.1038/385265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie GS, Davis I. Drosophila wingless and pair-rule transcripts localize apically by dynein-mediated transport of RNA particles. Cell. 2001;105:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yisraeli JK. VICKZ proteins: a multi-talented family of regulatory RNA-binding proteins. Biol Cell. 2005;97:87–96. doi: 10.1042/BC20040151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yisraeli JK, Sokol S, Melton DA. A two-step model for the localization of maternal mRNA in Xenopus oocytes: involvement of microtubules and microfilaments in the translocation and anchoring of Vg1 mRNA. Development. 1990;108:289–298. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon YJ, Mowry KL. Xenopus Staufen is a component of a ribonucleoprotein complex containing Vg1 RNA and kinesin. Development. 2004;131:3035–3045. doi: 10.1242/dev.01170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HL, Eom T, Oleynikov Y, Shenoy SM, Liebelt DA, Dictenberg JB, Singer RH, Bassell GJ. Neurotrophin-induced transport of a beta-actin mRNP complex increases beta-actin levels and stimulates growth cone Motility. Neuron. 2001;31:261–275. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao WM, Jiang C, Kroll TT, Huber PW. A proline-rich protein binds to the localization element of Xenopus Vg1 mRNA and to ligands involved in actin polymerization. EMBO J. 2001;20:2315–2325. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]