Abstract

Background:

Public sector health facilities were poorly managed due to a history of conflict in Nagaland, India. Government of Nagaland introduced “Nagaland Communitisation of Public Institutions and Services Act” in 2002. Main objectives of the evaluation were to review the functioning of Health Center Managing Committees (HCMCs), deliver health services in the institutions managed by HCMC, identify strengths as well as challenges perceived by HCMC members in the rural areas of Mokokchung district, Nagaland.

Materials and Methods:

The evaluation was made using input, process and output indicators. A doctor, the HCMC Chairman and one member from each of the three community health centers (CHC) and four primary health centers (PHC) were surveyed using a semi-structured questionnaire and an in-depth interview guide. Proportions for quantitative data were computed and key themes from the same were identified.

Results:

Overall; the infrastructure, equipment and outpatient/inpatient service availability was satisfactory. There was a lack of funds and shortage of doctors, drugs as well as laboratory facilities. HCMCs were in place and carried out administrative activities. HCMCs felt ownership, mobilized community contributions and managed human resources. HCMC members had inadequate funds for their transport and training. They faced challenges in service delivery due to political interference and lack of adequate human, material, financial resources.

Conclusions:

Communitisation program was operational in the district. HCMC members felt the ownership of health facilities. Administrative, political support and adequate funds from the government are needed for effective functioning of HCMCs and optimal service delivery in public sector facilities.

Keywords: Communitisation, community participation, Nagaland, public sector

Introduction

Community involvement is defined as a process by which partnership is established between the government and local communities in the planning, implementation and utilization of health related activities.[1] Active involvement of the community, in various maternal and child health interventions, through women groups and community health workers led to the reduction of neonatal, perinatal, and maternal mortality; as demonstrated by various studies from South Asia.[2] National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) has several components to engage the community, such as ASHA for improving health seeking behavior of the women and Rogi Kalyan Samitis (RKS) to increase public participation in the management of public sector facilities. Village health sanitation and nutrition committees (VHSNC) were also formed for encouraging involvement of the community in identifying health problems and facilitating the implementation of various health programs. In addition, community monitoring of the public sector health facilities was another innovative, pilot intervention that was introduced in a few states. Community rated the performance of the health facilities using color coded report cards.[3]

Govt. of Nagaland had passed “Nagaland Communitisation of Public Institutions and Services Act” in 2002 to encourage community participation, even prior to the NRHM.[4] Nagaland was established on 1st December 1963 and has population of 1.9 million as per the 2011 census.[5] Nagaland has a history of conflict due to the demand of an independent homeland since independence, however, the conflict has intensified in the past few decades. Poor governance and administration of various institutions led to dissatisfaction and lack of sense of ownership among the public.[6] Public sector health facilities were poorly managed with lack of transparency, accountability and high absenteeism among the providers.[4] In this context, communitisation was envisaged as an intervention. Communitisation is partnership between the government and the community for management of the public sector institutions to improve service delivery.[4] Although the program has been operational for several years, there was limited data regarding extent of implementation, service delivery in the facilities jointly managed by the community and government.

The main objectives of the evaluation were to review the functioning of Health Center Managing Committees (HCMCs) and health service delivery in the institutions managed by them. Strengths as well as challenges as perceived by HCMC members in the rural areas of Mokokchung district, Nagaland were also identified.

Materials and methods

Study site and study population

The Programme was evaluated in three CHCs and four PHCs in Mokokchung district, Nagaland. Each PHC caters to an approximate population of 7,000 and each CHC caters to a population of 50,000. Study population included the Medical officer in charge, the HCMC Chairman and one HCMC member from selected facilities.

Evaluation indicators

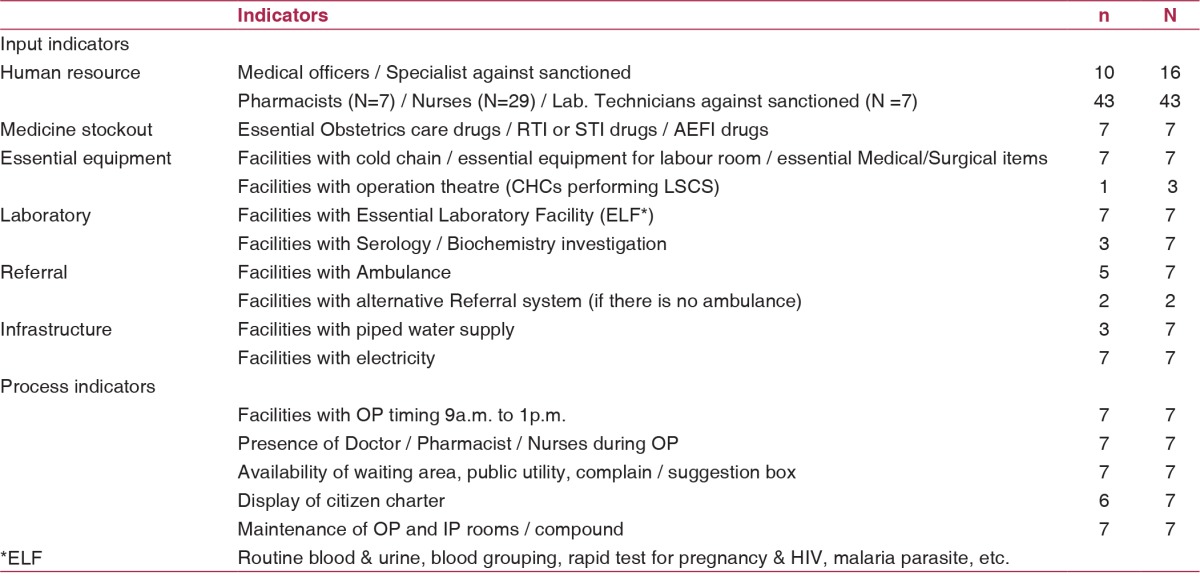

The program was evaluated using input, process and output indicators. Input indicators for service delivery included human resources, medicine stock, equipment, laboratory, ambulance and physical infrastructure. Process indicators included availability of outpatient (OP) services, availability of the staff during the working hours and maintenance of infrastructure. Output indicators included monthly OP and inpatient (IP) utilization during the previous year [Table 1].

Table 1.

Service delivery indicators in the Primary health centers and Community health centers, Mokokchung district, Nagaland, 2015 (N = 7)

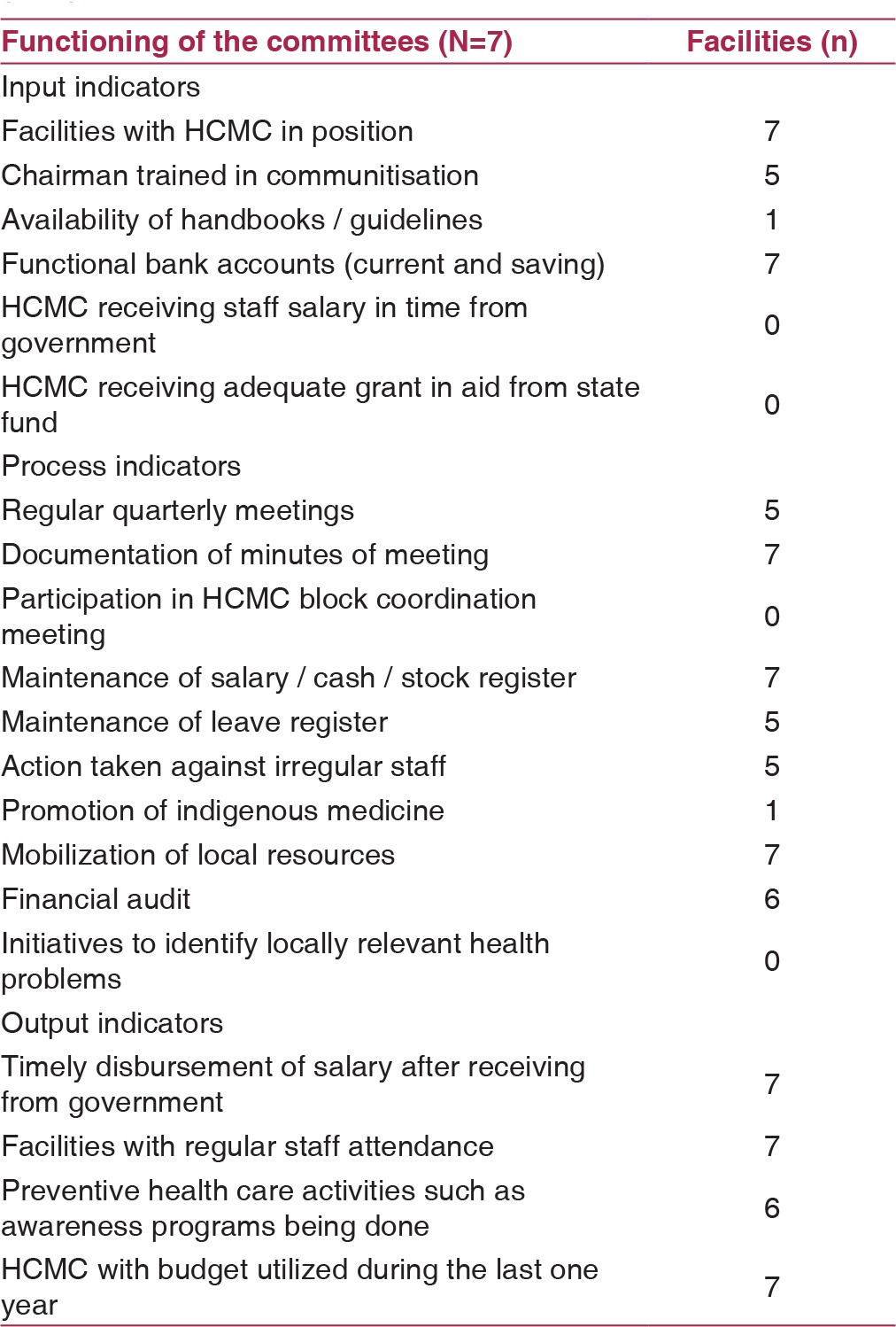

Input indicators for functioning of the HCMC included presence of HCMC, training of the HCMC Chairman, availability of handbook / guidelines and functional bank accounts. Process indicators included quarterly meetings, documentation of meeting proceedings, participation in block coordination meetings, maintenance of various registers, action taken for irregular staff, promotion of indigenous medicine, mobilization of local resources and financial audit. Output indicators included timely disbursement of staff salary, improved staff attendance, identification of corrective measures for health problems and utilization of budget in the previous one year [Table 2].

Table 2.

Indicators for functioning of Health Center Managing Committee, Mokokchung district, Nagaland, 2015 (N=7)

Evaluation design and data collection

Multiple methods were used for evaluation. Guidelines, handbooks on communitisation and records / registers maintained by the HCMC were reviewed. Medical officers were surveyed using a semi-structured questionnaire for facility related indicators. An observation check list was used for the infrastructure. The HCMC Chairman and one other member were both interviewed regarding the functioning of the HCMC using a semi-structured questionnaire. An in-depth interview guide was used to identify the strengths as well as challenges perceived by HCMC members in implementing various activities.

Operational definitions

Communitisation: Communitisation is defined as ownership and administrative, technical as well as financial management of PHC/CHC by the HCMC constituted as per guidelines.[4]

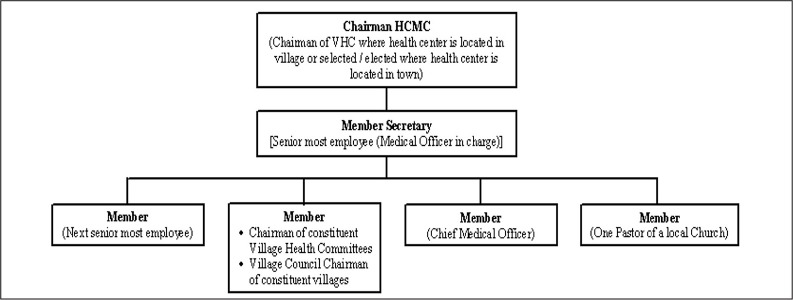

Health center managing committee (HCMC): HCMC consists of a Chairman, two members from the health care facility (one of them being the senior most doctor), members from constituent villages, local Church's Pastor and district Chief Medical Officer. Member secretary is the senior most employee of the facility [Figure 1]. They manage the curative, preventive health services and also promote traditional medicine.[4]

Figure 1.

Constitution of the Health center managing committees (HCMC), Mokokchung, Nagaland

Sampling strategy and sample size

All three CHCs and one PHC was selected from each of the four blocks of the district. One Medical officer, the Chairman of HCMC and one other member of the HCMC were all surveyed in each of the seven health facilities.

Data analysis

Frequencies and proportions for various input, process and output indicators were computed. Various themes were identified to elaborate upon the strengths as well as challenges faced by HCMC based on the qualitative narratives.

Human subject protection

Institutional Ethics committee of National Institute of Epidemiology (NIE) approved the study. Permission from the Chief Medical Officer, Mokokchung, Nagaland was also obtained. Free and informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Results

Description of the programme

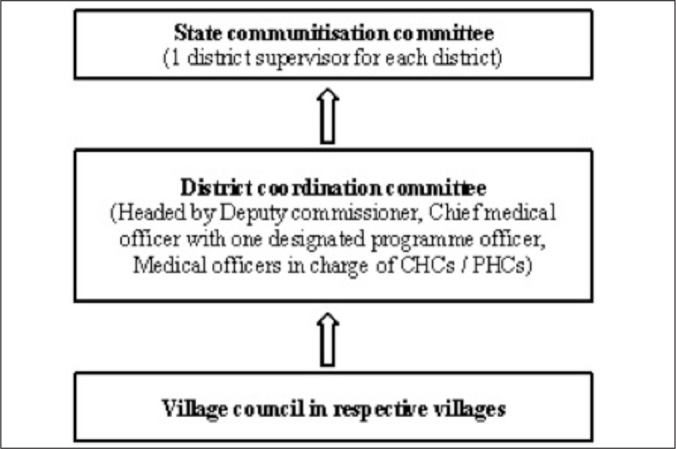

HCMC and Village health committees (VHC) were constituted in PHCs / CHCs and villages, respectively. HCMCs met once every quarter and had a tenure of three years. HCMCs were constituted as per specified guidelines (described earlier in the operational definitions). Assets, powers and management functions of the Government were transferred to the HCMC through a memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the Government and the Village Council. Two joint accounts were operationalized; saving account for developmental funds / grant in aid and current account for salaries. HCMC was carrying out the functions of managing material, human resources and maintenance of infrastructure. They were conducting review meetings and also, mobilizing local resources. The programme was monitored by the Village Council at village level, District Coordination Committee (headed by Deputy Commissioner) at the district level and State Communitisation Committee at the state level [Figure 2]. However, state government took the final decision concerning any difficulty, anomaly or doubt arising from the application of the rules.

Figure 2.

Monitoring / supervision mechanism of communitisation programme, Mokokchung, Nagaland

Evaluation of the programme

Service delivery

Paramedical human resources were in place as per the sanctions, however, there was a shortage of doctors (10/16). There was shortage of several essential drugs and only one facility had a functional operation theatre (OT) for lower segment caesarean section (LSCS). All the facilities had essential equipment for immunization and delivery services. All labs were carrying out hemoglobin, urine examination, HIV-ELISA and malaria rapid test; but the serology/biochemistry investigations were not available in 4 out of 7 laboratories. OP was conducted in all the facilities and staff was present during OP hours [Table 1]. The mean monthly OP was 513 per PHC and 444 per CHC. The mean monthly IP was 8 per PHC and 38 per CHC during 2013-2014.

Functioning of the Health center managing committee

HCMCs were in place in all the surveyed health institutions. Handbooks / guidelines were not available in 6 out of 7 facilities. Minutes of the meetings conducted by HCMC were available in all facilities. There was delay in receiving funds leading to delayed salary and other payments. HCMCs were performing various functions, such as the mobilization of resources, maintaining attendance and taking action against irregular staff, if necessary. However, participation in the coordination meetings at block level and promotion of indigenous medicine was lacking. All HCMCs utilized funds in the previous financial year and 6 of these carried out a financial audit [Table 2].

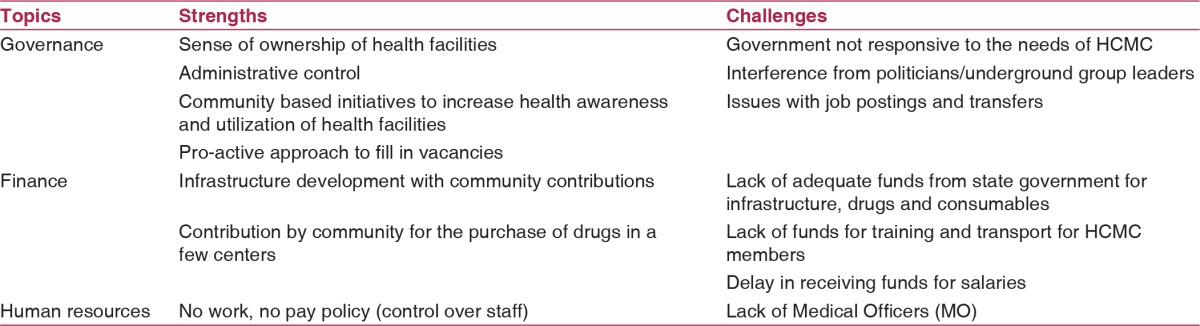

Strengths of the communitisation programme

We identified several themes based on in-depth interviews that highlighted the strengths of communitisation program as perceived by HCMC members [Table 3]. Ownership of health facilities by the community increased the contribution and utilization by village residents. HCMC members gradually understood that their role was much more than just monitoring the staff. HCMC members described their experiences as below:

Table 3.

Strengths as well as challenges of Communitisation programme identified by Health Center Managing Committee members during in-depth interviews, Mokokchung district, Nagaland

“After communitisation, many people now understand that the health center is our property” 63 years old male

“Earlier, the HCMC just checked staff attendance and thought the HCMC was to control the staff. But, now the HCMC understands the concept of communitisation” 47 years old male

“General nursing and midwifery (GNM) staff under NRHM was appointed due to the initiatives taken by the HCMC” 57 years old male

HCMC actively made efforts to increase health awareness and encouraged the community to use the health facilities. A male HCMC member narrated his experience as below:

“We do the public announcements and announcements in church; we also have a health center information board near the church for any health awareness information or activity” 84 years old male

Community gave contributions for construction of various facilities and purchase of office items, drugs and other consumables for the health centers. Various narratives below explain the contributions made by the community:

“The village council donated approximately Rs.34,592/- for furniture in the Health center; soiling of the approach road and footpath (steps) to the Health center; constructed water pipe line connection and placed health center information board near the church” 84 years old male

“Village council and student body at times donate money for medicines. Availability of medicines is largely due to the contributions by community, and not the government” 69 years old male

“A garage for ambulance was constructed through public donations; an individual has donated hardware tools to the Health center” 54 years old male

“Local youth club has constructed a waiting shed in the compound and a local union has constructed a toilet and bathroom” 57 years old male

Challenges faced by HCMC members

We identified several themes that highlighted the challenges faced by HCMC members in the management of the facility [Table 3]. Some of the major challenges were lack of Medical Officers as well as funds from the state government that had a negative impact on service delivery. HCMC members did not get adequate funds for transport and participation in various training programmes, meetings. In addition, the delay in receiving funds for staff salaries led to a delay in the payments. These issues were narrated by one of the HCMC members as below:

“There is lack of human resources and lack of funds that is a demotivating factor. We practically cannot function effectively due to failure of the Government to respond to the needs of the facility. There is also lack of mobility support.” 37 years old male

“With no public transportation, we spent few thousand of rupees on commuting to attend a training or meeting and get few hundred of rupees as travelling allowance” 47 years old male

Lack of availability of adequate human resources and inability to take action against absenteeism in few situations were major constraints experienced by the members. Members expressed their discontent over lack of initiative from the government to post doctors despite request from the HCMC. They also acknowledged the lack of willingness on the part of doctors to work in remote areas.

“There is lack of Medical Officers and patients have to be referred out. The Health center is only in name and there is hardly any benefit for the community with lack of Medical Officers” 63 years old male

“We don't allow substitute staff except when directed from higher ups. We have shortage of doctors, so we were asked to identify a doctor for ad hoc appointment. However, doctors don't want to stay in rural areas on ad hoc basis. We approached two doctors from the village, but they preferred working elsewhere.” 63 years old male

“Government has implemented the policy of ‘No work, no pay’. During our meeting, our second resolution was to implement a ‘No pay, no work’ policy. If we deduct even one day's salary, we develop enmity and spoil our relationships. Incapable staff should be terminated.” 84 years old male

HCMC members experienced many difficulties in managing the staff due to interference/pressures from political and pro independent homeland groups. The issues included postings and absenteeism that led to poor service delivery. The community, thus, had to face difficulties in accessing basic facilities such as immunization.

“A staff member posted in our health center was temporarily attached to another Health center. When we refused to release the staff due to shortage, the staff member called senior politicians. They telephoned and pressurized me to release him, however, I refused. Next day, the Medical Officer was also pressurized to release the staff member” 63 years old male

“Sometimes we face the problem of staff not attending duty with the backing of underground group leaders. I believe many officials must be facing the same problem and are unable to speak out. But we are not scared, we are the public, not Government servants; public has nothing to be scared of because we are doing what is written in the guide books” 54 years old male

“Five mothers from a neighboring village, five kilometers away, came walking with their children for vaccination, but due to a shortage of staff had to go back without vaccination” 63 years old male

Discussion

Overall, there have been improvements in the infrastructure and utilization of public sector facilities during the past decade, in Mokokchung district. We have no baseline survey, carried out prior to the launch of communitisation, to evaluate the effectiveness of the programme. Therefore, we have used the data available from the 2002-2004 district level survey. Coverage of services in the district was as follows: ante natal checkups 34%, institutional delivery 17% and full immunization 9%.[7] We compared these indicators with the recent DLHS-4 survey, conducted in 2012-2013, that reported antenatal checkup, institutional delivery and full immunization increased to 86%, 28% and 63%, respectively.[8] This might be due to combination of beginning of communitisation (2003-04) and launch of NRHM (2005-06).

Community participation has four conceptual approaches. These approaches include contributions, community empowerment, instrumental and developmental approaches.[9] Contributions and community empowerment approaches are suitable frameworks for interpreting the communitisation programme in Nagaland. Communitisation empowered the community to improve governance, service delivery and made the partnership with community that much stronger. The results of the study were encouraging and consistent with the literature from other developing countries. Effectiveness of community empowerment was also observed in studies from Azerbaijan and Papua New Guinea for improving health outcomes and reducing malaria mortality respectively.[10,11] In addition, community participation through involvement of community volunteers or health care workers led to better health seeking behaviour and improved maternal, child health indicators in studies from developing countries such as India, Bangladesh and Pakistan.[12,13,14] Community participation may not be able to achieve the health outcomes by itself in the absence of active involvement of government stakeholders. The challenges identified by the HCMC member such as inadequate funds from state budget for infrastructure/drugs, lack of funds for travel for HCMC members and political/pro independent homeland groups interference in the management of human resources can only be addressed by active involvement of the district /state administration.

The limitation of the study was lack of inclusion of Village health committees (Sub centers). Challenges perceived by the health facility staff due to communitisation were also not studied.

Communitisation programme built on the foundation of community spirit and bonding was effectively implemented in the Mokokchung district. HCMC members were able to discharge administrative/financial duties and had ownership of the facilities. They mobilized community resources and managed material, human resources well. The lack of doctors, poor administrative as well as financial support from the state government and an inadequate budget for infrastructure/drugs were the major constraints in ensuring adequate service delivery. HCMC members need to be trained and sensitized for identifying locally relevant health problems and strengthening preventive health care by actively engaging with the community. Administrative, political support and adequate funds from the government are needed for the effective functioning of HCMC as well as service delivery in public sector facilities.

Financial support and sponsorship

National Institute of Epidemiology, Chennai.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Government of Nagaland and the Chief Medical Officer, Mokokchung for granting us permission to evaluate the programme. We would like to convey our sincere gratitude to Dr. Tiasunep, the senior Medical Officer, Mokokchung for providing us with valuable inputs of the programme.

References

- 1.Kahssay HM, Oakley P. World Health Organization. Community involvement in health development: A review of the concept and practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999. p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marston C, Renedo A, McGowan CR, Portela A. Effects of community participation on improving uptake of skilled care for maternal and newborn health: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National rural health mission (NRHM) NRHM in the eleventh five year plan (2007-2012) New DelhiNational health systems resource center [Google Scholar]

- 4.Government of Nagaland HFWD Handbook on communitisation of health centers. Kohima: State communitization committee, department of Health and Family Welfare, Nagaland, Kohima; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5. [Last accessed on 2015 June 4];Office of the Registrar General I, India Nagaland Population Census data 2011 New Delhi, India: Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs. 2011 http://www.census2011.co.in/census/state/nagaland.html . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh M Amarjeet, The Naga Conflict Bangalore: National Institute of Advanced Studies. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reproductive and Child Health, District Level Household Survey (DLHS - 2), Nagaland 2002-04. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2006. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare ND. [Google Scholar]

- 8.District Level Household and Facility Survey-4, District Fact Sheet Mokokchung (2012-13) Mumbai: International institute for population sciences; 2012-13. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare GoI. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor J, Wilkinson D, Cheers B. Working with communities in health and human services. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzpatrick J, Ako WY. Empowering the initiation of a prevention strategy to combat malaria in Papua New Guinea. Rural and Remote Health. 2007;7:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikniaz A, Alizadeh M. Community participation in environmental health: Eastern Azerbaijan Healthy Villages project. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13:186–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule SB, Reddy MH, Deshmukh MD. Effect of home-based neonatal care and management of sepsis on neonatal mortality: Field trial in rural India. Lancet. 1999;354:1955–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baqui AH, El-Arifeen S, Darmstadt GL, Ahmed S, Williams EK, Seraji HR, et al. Effect of community-based newborn-care intervention package implemented through two service-delivery strategies in Sylhet district, Bangladesh: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1936–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhutta ZA, Memon ZA, Soofi S, Salat MS, Cousens S. Martines J, Implementing community-based perinatal care: Results from a pilot study in rural Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:452–9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.045849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]