Abstract

An actinomycete strain with a great potential to produce bioactive compounds isolated from a laterite soil was identified as Streptomyces sp. MSL based on 16S rDNA sequence analysis. Secondary metabolites produced by the strain in optimized nutrient broth were extracted and analyzed by chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques. Among the different fractions, four diols, viz., (1) (2R,3R)-2,3-Butanediol, (2) (2R,3S)-2,3-Butanediol, (3) 2,3-dimethyl-2,3-butanediol (Pinacol), and (4) (3R)-1,3-Butanediol exhibited good antimicrobial activity. These compounds inhibited growth of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as well as fungi tested. Minimum inhibitory concentration of these compounds was also determined against test micro-organisms in vitro. This is the first report on the occurrence of 2,3-dimethyl-2,3-butanediol (Pinacol) in the genus Streptomyces. This paper also reports the extraction, purification, and antimicrobial spectrum of diols fractionated from the culture filtrate of Streptomyces sp. MSL.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13205-017-0649-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: (2R,3R)-2,3-butanediol; (2R,3S)-2,3-butanediol; 2,3-dimethyl-2,3-butanediol (Pinacol); (3R)-1,3-butanediol; Streptomyces sp. MSL

Introduction

Natural product discovery is a major drive of product and process innovation in Biotechnology based industries (Bull et al. 2000). Natural products have been the most productive source of leads for the development of drugs. Most actinomycete species have the potential to synthesize many different biologically active secondary metabolites. A broad spectrum of biological activities have been detected such as antibacterial, antifungal, toxic, cytotoxic, neurotoxic, antimitotic, antiviral and antineoplastic. In more recent years, new targets have been added to the general screening including AIDS, immunosuppression, anti-inflammation, Alzheimer disease, ageing processes and some tropical diseases (Kelecom 1999). Among these compounds, antibiotics are much more important therapeutically and commercially. Approximately, two-thirds of known antibiotics have been isolated from actinomycetes (Olano et al. 2009). Actinomycetes have been especially useful to pharmaceutical industry for their unlimited capacity to produce secondary metabolites with diverse chemical structures and biological activities. They are broadly used in the human therapy, veterinary, agriculture, scientific research and in countless other areas. Discoveries of important, novel bioactive compounds depend upon the development of objective strategies for isolation and characterization of novel and rare micro-organisms for existing and new screens.

The genus Streptomyces, in particular, accounts for about 80% of the actinomycete natural products reported to date. Given the unparalleled potential of actinomycetes and specifically streptomycetes in this regard, significant effort has been directed towards isolation of these filamentous bacteria from various sources for drug screening programs. Streptomyces is a well-explored genus of Gram-positive bacteria in the phylum Actinobacteria. These prokaryotes present a strikingly similar lifestyle to that of filamentous fungi, and as do fungi, most Streptomycetes live as saprophytes in the soil (Lucas et al. 2013). Currently, it is reported that there are more than 2400 different secondary metabolites produced by Streptomyces spp. Scientists and researchers believe that there could be many more such metabolites with therapeutic potential to be discovered and explored (Genilloud et al. 2011). In this regard, the diversity of terrestrial actinomycetes has been of extraordinary significance in several areas of science and medicine.

The present study was mainly aimed to isolate and identify potent actinomycetes strain Streptomyces sp. MSL basing on morphological, biochemical, physiological, and cultural characteristics along with 16S rDNA sequencing and to screen its antimicrobial potential. Attempts were also made to characterize its bioactive compounds.

Materials and methods

Isolation of actinomycetes

Yeast extract malt extract dextrose agar medium (YMD) amended with streptomycin (50 µg/ml) and nystatin (100 µg/ml) was employed for selective isolation of soil actinomycetes. Soil samples randomly collected from laterite soil were air dried at room temperature for 48 h to reduce bacterial contaminants. Tenfold serially diluted soil sample (0.1 ml) was spreaded on YMD agar medium and incubated at 28–30 °C for 7 days. The predominant strain was subcultured and preserved on YMD agar slants at 4 °C (Williams and Cross 1971).

Identification of the potent strain

The strain was grown on seven International Streptomyces Project (ISP) media and five non-ISP media to determine cultural characteristics such as color of aerial mycelium and substrate mycelium, pigment production, and spore formation (Pridham et al. 1957). It was examined for morphological, biochemical, physiological, and cultural characteristics (Shirling and Gottlieb 1966; Ruan1977; Williams et al. 1983; Kampfer et al. 1991). Micromorphological characteristics were assessed with 4-day-old culture grown on YMD medium using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM: Model—JOEL-JSM 5600, Japan).

The strain grown in YMD broth for 3 days was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min and the pellet was used for extraction of DNA (Mehling et al. 1995). PCR mixture consisted of 2.5 μl of 10 × buffer, 3.5 μl of MgCl2 (25 mM), 2 μl of dNTP (0.4 mM), 1 μl of 16S rDNA actino specific primer—forward (10 pmol/μl), 1 μl of 16S rDNA actino specific primer—reverse (10 pmol/μl), Taq polymerase (2 U/μl) and 2 μl template DNA. PCR amplification was done with initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 3 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 65 °C for 1 min and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, with a further 5 min extension at 72 °C. The PCR product was purified with Agarose Gel DNA Purification Kit (SoluteReady® Genomic DNA purification kit, PCR Master Mix, Agarose gel electrophoresis consumables and Primers from HELINI Biomolecules, Chennai, India). The 750 bp 16S rDNA sequence was determined with 16S rDNA actino specific forward and reverse primers. The deduced 16S rDNA sequence was compared with the sequences in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) then aligned with related reference sequences retrieved from NCBI GenBank database using the Clustal W method. Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted using Molecular Evolutionary Genetic analysis (MEGA) version 4.0 (Tamura et al. 2007).

Growth pattern of the strain

To determine growth pattern, the strain was inoculated into 500 ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 200 ml YMD broth and flasks were incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for optimum yields on a rotary shaker at 180 rpm. At every 24 h interval, flasks were harvested; growth of the strain was measured by weighing the dry weight of biomass, and antimicrobial metabolites production was determined in terms of antimicrobial spectrum. The culture filtrates were extracted with ethyl acetate and antimicrobial activity of crude extract was determined by agar-well diffusion method.

Fermentation and extraction of bioactive compounds of the strain

Fermentation was carried out in 1 L Roux bottles for 120 h at 30 °C. The broth was harvested by the filtration of biomass through Whatman filter paper no. 42 (Merck, Mumbai, India). The culture filtrate was extracted twice with an equal volume of ethyl acetate, and the combined organic layers were concentrated with a Rotavac. The deep brown concentrated semisolid compound was used as the crude bioactive extract.

Antimicrobial assay

The antimicrobial activity of metabolite produced by the strain was determined by agar-well diffusion method. Nutrient agar (NA) and Czapek-Dox (CD) agar media were used for culturing test bacteria and fungi, respectively. NA medium (100 ml) was sterilized at 15lbs pressure (121 °C) for 15 min, cooled, and inoculated with 0.2 ml of test bacterial suspension. After thorough mixing, the seed medium was poured into Petri plates under aseptic conditions. After solidification of agar medium, wells of about 6 mm diameter were punched into it with sterilized cork borer. For antifungal assay, spore suspension of test fungi was mixed with cooled, molten CD agar medium, and poured into Petri dishes. The crude extract dissolved in ethyl acetate at a concentration of 50 ppm was added to each well. Adding only ethyl acetate to the wells served as control. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h for bacteria and 24–72 h for yeast and filamentous fungi, and diameter of inhibition zones was measured.

Test micro-organisms

Bacillus cereus, B. megaterium, B. subtilis, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella sp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, P. solanacearum, Salmonella typhi, Shigella flexneri, Staphylococcus aureus, Vibrio cholerae, and Xanthomonas campestris were used as test bacteria and test fungi include Alternaria sp., Asperigillus niger, Botrytis cinerea, Candida albicans, Fusarium solani, F. oxysporum, and Verticillium alboatrum.

Extraction, isolation and purification of bioactive compounds produced by the strain

For the extraction of bioactive compounds, 5% of seed broth was inoculated into optimized production medium (galactose @ 6 g, yeast extract @ 10 g, malt extract @ 10 g, and sodium chloride @ 10 g dissolved in 1 L distilled water with pH 7.0) for enhanced secondary metabolite production. Fermentation was carried out in 1 L Roux bottles for 120 h at 30 °C. The harvested broth (25 L) extracted with ethyl acetate was concentrated in a Rotavac. The deep brown concentrated semisolid compound (3.21 g) obtained was applied to a silica gel G column (80 × 2.5 cm, silica gel, Merck, Mumbai, India). Separation of crude extract was conducted via gradient elution with hexane: ethyl acetate. The eluent was run over the column and small volumes of eluent collected in test tubes were analyzed via thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using silica gel plates (Silica gel, Merck, Mumbai, India) with hexane: ethyl acetate solvent system. Compounds with identical retention factors (R f) were combined and assayed for antimicrobial activities. The crude eluent was recuperated in 5–10 ml of ethyl acetate, and was further purified.

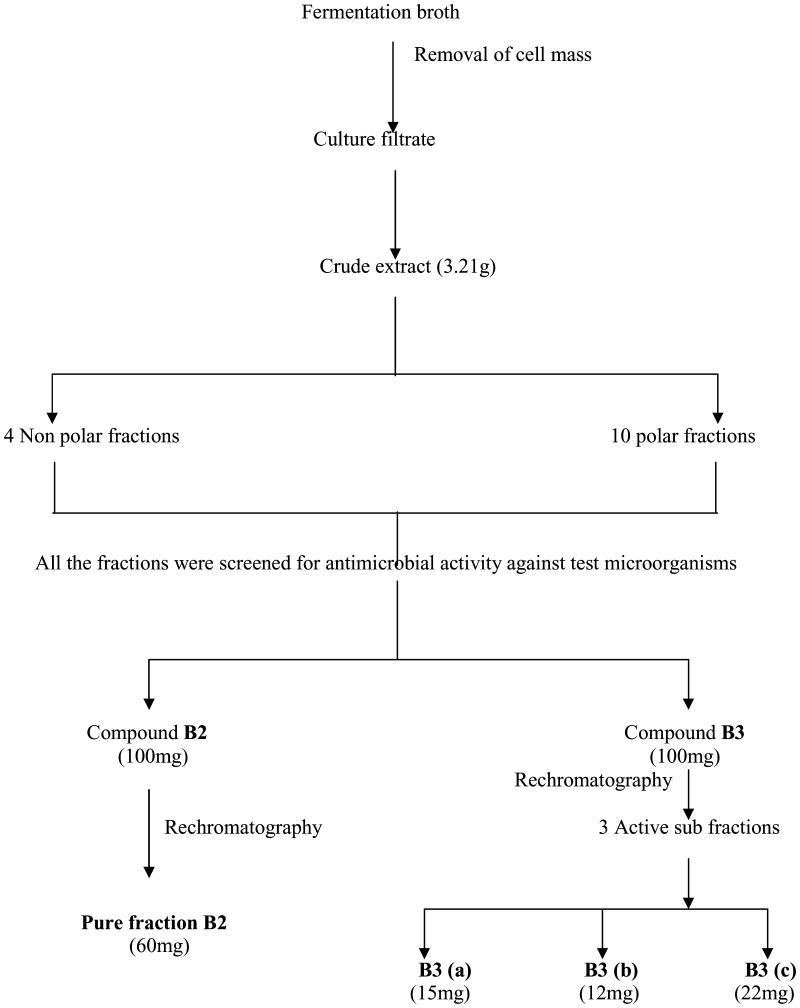

Among the 14 main fractions eluted, 10 fractions were polar and 4 were non-polar residues. Two biologically active fractions (B2, eluted at 70–30v/v and B3 eluted at 60–40v/v) were selected for further studies and the non-polar fractions did not exhibit antimicrobial activity. Fraction B2 (100 mg) and B3 (100 mg) were rechromatographed to obtain in pure form. The structures of these active fractions were analyzed on the basis of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR); model: Thermo Nicolet Nexus 670 spectrophotometer with NaCl optics, Electron Ionization Mass/Electron Spray Ionization Mass Spectrophotometry (EIMS/ESIMS); model: Micromass VG—7070H, 70 eV spectrophotometer, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H NMR and 13C NMR) model: Varian Gemini 200 and samples were made in CDCl3 with Trimethyl silane as standard.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of isolated compounds

Antibacterial activities of the fractions were done by micro-dilution method in 96 well microplates. The bioactive fractions were dissolved in MeOH to prepare required concentrations of compounds ranging form 0 to 500 µg/ml. Each well was inoculated with 10 µl of suspension containing 105 CFU/ml of test bacteria. Antibiotic tetracycline was used as positive control. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation 10 µl of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium, chloride was added to each well. Appearance of red color indicates bacterial growth, while the absence of color indicates inhibition of bacterial growth by bioactive compounds. Similar to determine MIC of the compound against test fungi, 105 spores/ml were dispensed into 24 well microtitre plates. Increasing concentrations of compounds (0–500 µg/ml) was added to the wells and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C. The concentration of compounds that completely inhibited the growth of test micro-organisms was recorded after 3–4 days.

Results and discussion

Identification of the strain

A predominant strain isolated from laterite soil exhibited significant inhibitory activity against selected bacterial and fungal cultures (Table 1). This strain has been identified and used for isolation of bioactive metabolites. The strain grew on a range of agar media, evidencing the typical morphology of Streptomyces. The substrate mycelium was brown, while aerial mycelium tended to be creamy white differentiated into spiral chains of spores with rough surface (Fig. 1a, b). It produced a pink diffusible pigment on starch casein agar medium. The physiological and biochemical characteristics of strain were recorded in Table 2. Enzymatic profile of the strain was interesting as it is a producer of a wide range of commercially important enzymes, such as amylase, protease, pectinase, cellulase, chitinase, and keratinase. The strain when tested for its antibiotic sensitivity against several antibiotics showed resistance to gentamicin, streptomycin, and vancomycin and was susceptible to other antibiotics tested.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial profile of Streptomyces sp. MSL isolated from laterite soil

| Test organism | Zone of inhibition (mm) |

|---|---|

| Bacteria | |

| Bacillus cereus | 22 |

| B. megaterium | 18 |

| B. subtilis | 16 |

| Corynebacterium diphtheriae | 19 |

| Escherichia coli | 17 |

| Klebsiella sp. | 20 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 22 |

| Salmonella typhi | 20 |

| Serratia marcescens | 11 |

| Shigella flexneri | 19 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 23 |

| Vibrio cholerae | 22 |

| Xanthomonas campestris | 15 |

| Fungi | |

| Aspergillus niger | 25 |

| Botrytis cinerea | 14 |

| Candida albicans | 18 |

| Fusarium oxysporum | 16 |

| F. solani | 16 |

| Verticillium alboatrum | 12 |

| Alternaria sp. | 9 |

Fig. 1.

a Spiral spore chains of Streptomyces sp. MSL. b Rough surface of spores of Streptomyces sp. MSL

Table 2.

Physiological and biochemical characteristics of the predominant strain isolated from laterite soil

| Carbon utilization (w/v)* | Sodium Chloride tolerance (%)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | +++ | 0–1 | +++ |

| Xylose | + | 1.5 | ++ |

| Sucrose | ++ | 2–3 | + |

| Raffinose | + | 3.5–7 | − |

| Starch | +++ | Biochemical characteristics: | |

| Galactose | +++ | Indole | P |

| Maltose | ++ | Methyl red | N |

| Fructose | ++ | Voge’s Proskaeur | N |

| Lactose | + | Citrate utilization | P |

| Glycerol | + | H2S production | P |

| Mannitol | + | ||

| Nitrogen source (w/v)* | Growth in the presence of antibiotics (µg/ml): | ||

| Yeast extract | +++ | Ampicillin (10) | S |

| Peptone | ++ | Chloramphenicol (10) | S |

| Tryptone | +++ | Gentamicin (30) | R |

| Asparagine | ++ | Neomycin (15) | S |

| Tyrosine | + | Penicillin (25) | S |

| Ammonium nitrate | + | Rifampicin (20) | S |

| Sodium nitrate | + | Streptomycin (50) | R |

| Potassium nitrate | + | Tetracycline (35) | S |

| Enzymatic activity | Vancomycin (30) | R | |

| Amylase | P | ||

| Cellulase | P | ||

| Chitinase | P | ||

| Keratinse | P | ||

| Pectinase | P | ||

| Protease | P | ||

* Growth of the strain measured as dry weight of the mycelium

+++ good growth, ++ moderate growth, + weak growth, − indicates negative/no growth; S sensitve, R resistant, P positive, N negative

The strain utilized d-galactose, d-glucose, arabinose, starch, sucrose, maltose, and fructose as sole carbon sources when compared to lactose, raffinose, glycerol, and mannitol. It exhibited good growth with organic nitrogen sources, viz, yeast extract, tryptone, peptone, and asparagine, while inorganic nitrogen sources, such as sodium nitrate, potassium nitrate, and ammonium nitrate, did not support the growth. The isolate was indole positive and utilized citrate as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen. It showed negative results for methyl red and Voges Proskauer tests. Comparison of biochemical and morphological characteristics of the strain with those reported in Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology 14revealed its identity as Streptomyces (Buchana and Gibbons 1974).

For molecular characterization, the 16S rDNA sequence of strain (deposited in NCBI Genbank with an accession number JN102132) was compared with sequences in GenBank using BLAST and aligned with sequences retrieved from NCBI GenBank database using Clustal W method. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on maximum parsimony method using bootstrap analysis (Fig. 2). The strain was close to Streptomyces viridis with a bootstrap value of 53.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of Streptomyces sp. MSL

Isolation, purification and identification of bioactive metabolites produced by Streptomyces sp. MSL

The flow chart for isolation and purification of active fractions was illustrated in Fig. 3. The deep brown semi solid (3.21 g) obtained by concentrating ethyl acetate extract of fermentation broth was applied to a silica gel G column. Among the different fractions, fractions B2 and B3 showing higher antimicrobial activity were rechromatographed on silica gel column to yield B2 (60 mg) in pure form and three subfractions from B3, namely, B3 (a), B3 (b), and B3 (c), were obtained.

Fig. 3.

Flowchart of isolation and purification of bioactive compounds produced by the strain

Structural elucidation of B2 and B3 compounds

The fraction B2 was rechromatographed via silica gel column with hexane: ethyl acetate (70-30v/v). The compound in pure form appeared as white solid soluble in CHCl3, MeOH, DCM, and DMSO. Structural elucidation of this active fraction was done with FTIR, EIMS/ESIMS, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR. The IR absorption maxima V max at 3422 cm−1 suggested the presence of functional OH group (Fig. S1). In ESIMS, the compound showed molecular ions at m/z = 119 inferring a molecular weight of C6H15O2 [M + 1]+ (Fig. S2). The proton NMR of compound displayed two exchangeable protons at δ 1.57 (br s, 2OH) and four methyl groups at δ 1.25 (6H, d, J = 5.95 Hz) (Fig. S3). 13C NMR depicted peaks at δ 75.17.(2C) and at δ 24.87(4C) (Fig. S4). Based on spectral data, the B2 fraction was identified as 2,3-dimethyl-2,3-butanediol (Pinacol) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

2,3-dimethyl-2,3-butanediol (Pinacol)

The fraction B3 when rechromatographed via silica gel column using hexane: ethyl acetate eluent system (30–70v/v), three subfractions B3 (a), B3 (b), and B3(c) were obtained (Fig. 5). B3 (a) fraction eluted with 35% ethyl acetate appeared as light brown liquid soluble in CHCl3, MeOH, DCM, and DMSO. The structure of this active fraction was analyzed with FTIR, ESIMS, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR. The IR absorption maxima V max at 3437 cm−1 suggested the presence of functional OH group (Fig. S5). In ESIMS, the compound showed molecular ions at m/z = 108 inferring a molecular weight of C4H28O2 [M + NH3]+ (Fig. S6). The proton NMR of compound displayed proton signals at δ 3.81 (2H, Qd, J = 6.04 Hz) due to methylene protons bearing hydroxyl group, two exchangeable protons at δ 1.93 (br s, OH), at δ 1.67 (br s, OH) and two methyl groups at δ 1.15 (6H, d, J = 6.04 Hz) (Fig. S7). 13C NMR depicted peaks at δ 70.81 (2C) and at δ 16.90 (2C). {α}-25D = −12.5 (c = 1, CHCl3) (Fig. S8). Based on spectral data and optical rotation, B3 (a) was identified as (2R,3R)-2,3-Butanediol (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

Three subfractions B3 (a), B3 (b), and B3(c) obtained from main fraction B3, respectively a (2R, 3S)-2,3-Butanediol; b (2R,3R)-2,3-Butanediol; c (3R)-1,3-Butanediol

B3(b) fraction eluted with 50% ethyl acetate also appeared as light brown liquid which was soluble in MeOH, DCM, and DMSO. The IR absorption maxima V max at 3440 cm−1 suggested the presence of functional OH (Fig. S9). In ESIMS, the compound showed molecular ions at m/z = 90 inferring a molecular weight of C4H10O2 [M]+ (Fig. S10). The proton NMR of compound displayed proton signals at δ 3.78 (2H, Qd, J = 5.95, 2.32 Hz) due to methylene protons bearing hydroxyl group, two exchangeable protons at δ 2.65 (br s, 2OH) and two methyls at δ 1.11 (6H, d, J = 5.95 Hz) (Fig. S11). 13C NMR depicted peaks at δ 70.78 (2C) and at δ 16.84 (2C). {α}-25D = 0 (c = 1, CHCl3) (Fig. S12). B3 (b) bioactive fraction was identified as (2R,3S)-2,3-butanediol (Fig. 5b) based on spectral data and optical rotation.

B3(c) fraction was also eluted at 50% ethyl acetate and appeared as light brown liquid soluble in CHCl3, MeOH, and DCM. The IR absorption maxima V max at 3292 cm−1 suggested the presence of functional OH (Fig. S13). In ESIMS, the compound showed molecular ions at m/z = 113 inferring a molecular weight of C4H10O2Na [M + Na]+ (Fig. S14). The proton NMR of compound displayed proton signals at δ 4.08 (1H, m) due to C-3 methylene protons bearing hydroxyl group, the signals at δ 3.84 (2H, m) due to C-1 methylene proton bearing hydroxyl group, two exchangeable protons at δ 2.4 (br s, OH), two methylene protons at δ 1.7 (2H, m), and two methyl protons at δ 1.24 (3H, d, J = 6.4 Hz) (Fig. S15). 13C NMR depicted peaks at δ 67.1 (1C), 60.6 (1C), 40.0 (1C), and at δ 23.4 (1C). {α}-25D = −30.5 (c = 1, EtOH) (Fig. S16). B3(c) fraction was identified as (3R)-1,3-butanediol (Fig. 5c) based on spectral data and optical rotation.

Biological activities of isolated compounds

All the four chiral compounds fractionated from the culture filtrate of Streptomyces sp. MSL exhibited good antibacterial activity than antifungal activity. Among the four active fractions, (2R,3R)-2,3-Butanediol and (2R,3S)-2,3-Butanediol had greater antimicrobial profile than the other two fractions. The MIC of active fractions was shown in Table 3. Among the four fractions B3(a) and B3(b) exhibited good MIC followed by B3(C) and B2. Pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria tested, namely, S. typhi, S. flexneri, V. cholerae, and X. campestris, were highly sensitive to these metabolites. The genus Streptomyces remains as an outstanding resource for isolation of novel and potent bioactive metabolites, such as 3-phenylpropionic acid, anthracene-9,10-quinone, and 8-hydroxyquinoline by Streptomyces sp. ANU 6277 (Narayana et al. 2008) and chloropyrrol and chlorinated anthracyclinone from Streptomyces MaB-QuH-8 (Pullen et al. 2002). Gohar et al. (2006) reported that proteopolysaccharide produced by Streptomyces nasri isolated from Kuwait tropical soil showed antimicrobial activity against a wide range of micro-organisms (Gohar et al. 2006).

Table 3.

MIC of the bioactive compounds produced by Streptomyces sp. MSL

| Test organism | MIC (µg/ml) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B2 | B3(a) | B3(b) | B3(c) | Positive control | |

| Bacteria | |||||

| Bacillus cereus | 30 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 15 |

| B. megaterium | 25 | 20 | 30 | 25 | 25 |

| B. subtilis | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Corynebacterium diphtheriae | 45 | 55 | 55 | 45 | 30 |

| Escherichia coli | 35 | 45 | 35 | 30 | 20 |

| Klebsiella sp. | 45 | 35 | 35 | 30 | 35 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 45 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 40 |

| Salmonella typhi | 50 | 45 | 45 | 55 | 45 |

| Serratia marcescens | 35 | 30 | 35 | 35 | 25 |

| Shigella flexneri | 20 | 20 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 25 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 20 |

| Vibrio cholera | 40 | 30 | 35 | 35 | 30 |

| Xanthomonas campestris | 35 | 25 | 20 | 30 | 25 |

| Fungi | |||||

| Aspergillus niger | 35 | 35 | 45 | 45 | 5 |

| Botrytis cinerea | 25 | 20 | 45 | 30 | 10 |

| Candida albicans | 25 | 20 | 35 | 35 | 10 |

| Fusarium oxysporum | 30 | 25 | 25 | 20 | 10 |

| F. solani | 35 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 10 |

| Verticillium alboatrum | 45 | 35 | 30 | 20 | 10 |

| Alternaria sp. | 25 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 5 |

B2 2,3-dimethyl-2,3-butanediol, B3(a) (2R,3R)-2,3-Butanediol, B3(b) (2R,3S)-2,3-Butanediol, B3(c) (3R)-1,3-Butanediol

Positive control Tetracycline for bacteria and Nystatin for fungi

The study of Roy et al. (2006) stated that dibutyl phthalate produced by Streptomyces albidoflavus 321.2 showed strong activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as well as unicellular and filamentous fungi. 1,3-dihydroxybutane was reported to be active against Aspergillus niger (Rehn 1983; Rehn et al. 1984). An active compound produced by Streptomyces aureocirculatus (Y10) showed good activity against MRSA, VRSA, and ESBL pathogens (Pazhani Murugan et al. 2010). Streptomyces spp. isolated from Mediterranean Sponges were reported to produce antiparasitic compounds, such as valinomycin, staurosporine, and butenolide (Pimentel-Elardo et al. 2010). Three antimycobacterial (anti-Mycobacterium bovis) metabolites recovered from culture broth of a marine derived Streptomyces sp. MS100061which were identified as a new spirotetronate, lobophorin G (1), together with two known compounds, lobophorins A (2) and B (3). (Chen et al. 2013). Vineomycin A1 and chaetoglobosin A reported from Streptomyces sp. PAL114 showed a strong activity especially against Candida albicans, Bacillus subtilis, and Staphylococcus aureus (Aouiche et al. 2015).

2,3-Butanediol also known as 2,3-butylene glycol, dimethylene glycol, or 2,3-dihydroxybutane is an odorless liquid of high boiling point. It is a promising chemical used in a variety of chemical feed stocks, liquid resources, antifreeze agents, and also as drug carrier (Syu 2001). During the last few decades, considerable efforts have been made to improve the production of 2,3-butanediol from fermentation, and much progress has been achieved (Qin et al. 2006; Zeng et al. 1991). This compound could not be easily recovered by conventional distillation because of its high boiling point (about 180 °C). Li-Hui et al. (2009) reported a novel aqueous two-phase system consisted of 2-propanol/ammonium sulfate used for extraction of 2,3-butanediol from fermentation broths (Li-Hui et al. 2009). It can be further converted to 1,3-dihydroxybutane which is used in the production of synthetic rubber. This is the first report of pinacol (2,3-dimethyl-2,3-butanediol) production from actinomycetes and from the genus Streptomyces, in particular.

Conclusions

The present study revealed that the strain Streptomyces sp. MSL served as a good source for production of bioactive diols with good antagonistic activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors (MRHB, MVL, and MRK) are grateful to the University Grants Commission, New Delhi as this work was supported in part by UGC Major Research project and DKR and YV are thankful to the Director, IICT, Hyderabad and CSIR, New Delhi.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13205-017-0649-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Aouiche A, Meklat A, Bijani C, Zitouni A, Sabaou N, Mathieu F. Production of vineomycin A1 and chaetoglobosin A by Streptomyces sp. PAL114. Ann Microbiol. 2015;65:1351–1359. doi: 10.1007/s13213-014-0973-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchana RE, Gibbons NE. Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology. 8. Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Company; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Bull AT, Ward AC, Goodfellow M. Search and discovery strategies for biotechnology: the paradigm shift. Microbiol Mol Bio Rev. 2000;64:573–606. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.3.573-606.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Wang J, Guo H, HouW Yang N, Ren B, Liu M, Dai H, Liu X, Song F, Zhang L. Three antimycobacterial metabolites identified from a marine-derived Streptomyces sp. MS100061. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:3885–3892. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genilloud O, Gonzalez I, Salazar O, Martin J, Tormo JR. Current approaches to exploit actinomycetes as a source of novel natural products. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;38:375–389. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0882-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohar Y, Beshay U, Daba A, Hafez E. Bioactive compounds from Streptomyces nasri and its mutants with special reference to proteopolysaccharides. Pol J Microbiol. 2006;55:179–187. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampfer P, Kroppenstedt RM, Dott W. A numerical classification of the genera Streptomyces and Streptoverticillium using miniaturized physiological tests. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1831–1891. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-8-1831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelecom A. Chemistry of marine natural products: yesterday, today and tomorrow. An Acad Bras Cienc. 1999;71:249–263. [Google Scholar]

- Li-Hui S, Bo J, Zhi-Long X. Aqueous two-phase extraction of 2,3-butanediol from fermentation broths by isopropanol/ammonium sulfate system. Biotechnol Lett. 2009;31:371–376. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9874-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas X, Senger C, Erxleben A, Grüning BA, Döring K, Mosch J, Flemming S, Günther S (2013). Streptome ***DB: a resource for natural compounds isolated from Streptomyces species. Nucl Acids Res (Database Issue) D1130–D1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mehling A, Wehmeier UF, Piepersberg W. Nucleotide sequences of streptomycete 16S ribosomal DNA: towards a specific identification system for streptomycetes using PCR. Microbiol. 1995;141:2139–2147. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-9-2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayana KJP, Prabhakar P, Vijayalakshmi M, Venkateswarlu Y, Krishna PSJ. Study on Bioactive compounds from Streptomyces sp. ANU 6277. Pol J Microbiol. 2008;57:35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olano C, Méndez C, Salas JA. Antitumor compounds from marine actinomycetes. Mar Drugs. 2009;7:210–248. doi: 10.3390/md7020210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazhani Murugan R, Radhakrishnan M, Balagurunathan R. Bioactive sugar molecule from Streptomyces aureocirculatus (Y10) against MRSA, VRSA and ESBL pathogens. J Pharm Res. 2010;3(9):2180–2181. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel-Elardo SM, Kozytska S, Bugni TS, Ireland CM, Moll H, Hentschel U. Anti-parasitic compounds from Streptomyces sp. strains isolated from mediterranean sponges. Mar Drugs. 2010;8:373–380. doi: 10.3390/md8020373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pridham TG, Anderson P, Foley C, Lindenfelser LA, Hesseltine CW, Benedict RG. A selection of media for maintenance and taxonomic study of Streptomyces. Ant Ann. 1957;57:947–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullen C, Schmitz P, Meurer K, Bamberg DD, Lohmann S, De Castro França S, Groth I, Schlegel B, Möllmann U, Gollmick F, Gräfe U, Leistner E. New bioactive compounds from Streptomyces strains residing in the wood of Celastraceae. Planta. 2002;216:162–167. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0874-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin JY, Xiao ZJ, Ma CQ, Xie NZ, Liu PH, Xu P. Production of 2,3-butanediol by Klebsiella pneumonia using glucose and ammonium phosphate. China J Chem Engg. 2006;14:132–136. doi: 10.1016/S1004-9541(06)60050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rehn D. Quantitative structure activity considerations on the spore-inhibiting activity of esters of 1, 3-dihydroxybutane. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1983;5:701–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehn D, Siegert W, Nolte H. Antimicrobial activity of linear esters of 1,3-dihydroxybutane. Pharm Acta Helv. 1984;59:162–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy RN, Laskar S, Sen SK. Dibutyl phthalate, the bioactive compound produced by Streptomyces albidoflavus 321.2. Microbiol Res. 2006;161:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan JS. The basis of taxonomy of actinomycetes. Beijing: The Chinese Academic Press; 1977. pp. 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Shirling EB, Gottlieb D. Methods for characterization of Streptomyces species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1966;16:313–340. doi: 10.1099/00207713-16-3-313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Syu MJ. Biological production of 2,3-butanediol. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;55:10–18. doi: 10.1007/s002530000486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ST, Cross T. Actinomycetes. In: Booth C, editor. Methods in microbiology. London: Academic press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Williams ST, Goodfellow M, Alderson G, Wellington FMH, Sneath PHA, Sackin MJ. Numerical classification of Streptomyces and related genera. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:1743–1813. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-6-1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng AP, Biebl H, Deckwer WD. Production of 2,3-butanediol in a membrane bioreactor with cell recycle. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;34:463–468. doi: 10.1007/BF00180571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.