Abstract

Immobilized Candida tropicalis cells in freeze dried calcium alginate beads were used for production of xylitol from lignocellulosic waste like corn cob hydrolysate without any detoxification and sterilization of media. Media components for xylitol fermentation were screened by statistical methods. Urea, KH2PO4 and initial pH were identified as significant variables by Plackett–Burman (PB) design. Significant medium components were optimized by response surface methodology (RSM). Predicted xylitol yield by RSM model and experimental yield was 0.87 and 0.79 g/g, respectively. Optimized conditions (urea 1.5 g/L, KH2PO4 1.9 g/L, xylose 55 g/L, pH 6.7) enhanced xylitol yield by 32% and xylose consumption by twofold over those of basal media. In addition, the immobilized cells were reused five times at shake flask level with optimized medium without affecting the xylitol productivity and yield. Xylitol production was successfully scaled up to 7.5 L stirred tank reactor using optimized media. Thus, the optimized condition with non-detoxified pentose hydrolysate from corn cob lignocellulosic waste with minimal nutrients without any sterilization opens up the scope for commercialization of the process.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13205-017-0700-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cell immobilization, Xylitol, Non-detoxified, Non-sterile, Lignocellulose, Optimization

Introduction

Xylitol, a pentitol, is known to be useful for diabetic patients because of its low calorific value and equal sweetness index in comparison to sucrose (Pepper and Olinger 1988). In addition, it helps to reduce dental caries (Ylikahri 1979). Xylitol is known to prevent ear infection in children (Uhari et al. 1996) and is used in personal health products like mouth washes and tooth paste (Affleck 2000). Furthermore, xylitol is US-FDA approved for use in foods, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and oral health products in more than 50 countries (Povelainen 2008). Nowadays, because of above mentioned facts and increasing health consciousness among consumers, there is rising demand for xylitol in health improving products. In spite of this demand, the relatively scarce worldwide production of xylitol can be attributed to the high cost (6.39 $/kg) of chemical production method (Tran et al. 2004). Currently, xylose is obtained from corn cob by acid hydrolysis, followed by purification with chromatography. Xylitol is commercially produced by hydrogenation of pure xylose using Raney nickel catalyst at high temperature and high pressure. Hence, xylitol production by biotechnological route has become an attractive alternative to chemical production as mild conditions are required for the reaction and does not require pure xylose.

For industrial xylitol application, xylitol yield and substrate consumption must be higher and production process costs cheaper. Low-cost xylitol production involves use of crude xylose without any detoxification, recycling of yeast cells, high xylose to xylitol yield, high productivity, high titer of xylitol, less energy input, easy downstream processing to purify xylitol, and use of fermentation media with use of minimal industrial nutrients. Hence, it is very necessary that carbon, nitrogen, minerals, and other nutrients including process parameter must be economically competitive to ensure the commercial feasibility of fermentation process with improved fermentation performance.

Corncob is a major lignocellulosic waste generally employed as animal feed and recycled as fertilizer in soil, or as a fuel. The corn cob waste after acid hydrolysis can be used as a raw material for xylose (Rivas et al. 2002), which will reduce the cost of xylitol production (as compared to use of pure xylose). Urea and ammonium sulphate are generally preferred nitrogen sources in industrial fermentation as economic nutrients.

The efficiency of the xylitol fermentation can be augmented using high cell concentrations, which can be achieved with immobilized cell system. The immobilized microorganism system can be used to improve the fermentation performance and to reduce the overall production costs (Roberto et al. 1991). Immobilized cell bioprocesses are preferred as compared to free cells, because they allow higher fermentation rates, permit high cell concentration, recycling of cells for extended time, reduce costs related to seed development, protect the entrapped biocatalyst from inhibitors, prevent washout of cells, and provide ease of separation of biocatalyst from fermentation broth (Jirku et al. 2000). Particularly, immobilization in calcium alginate beads stands out, because their production method does not require drastic conditions and utilizes ingredients that are accepted as food additives (Champagne et al. 2000). Hence, the optimization of media components and fermentation parameters with immobilized system plays an important role in improving fermentation performance yield and commercial feasibility. Application of statistical methods enables easy selection of various important fermentation parameters and helps in understanding their interaction. A number of statistical experimental designs have been used for optimizing fermentation variables. Plackett–Burman (PB) design is a well-established and widely used statistical technique for screening of significant culture variables (Plackett and Burman 1946). Response surface methodology is used for finding the optimum level of each variable along with its interactions with other variables and their effects on product yield (Gu et al. 2005).

The present study reports a highly efficient fermentation process for xylitol production using non-detoxified and non-sterilized corn cob hydrolysate. Alginate-entrapped C. tropicalis yeast cells were found to support high and sustainable xylitol production up to eight cycles of repeated-batch fermentation in shake flask (Yewale et al. 2016). C. tropicalis was used for xylitol production. Furthermore, optimization of conditions for xylitol production using cheap feedstock usually used in industrial fermentation was attempted. Statistical optimization was performed in two steps: (1) Plackett–Burman design used for screening of most significant media components and process parameters; (2) RSM was used for further optimization to enhance the xylitol yield using the significant process variable. Reusability of cells was performed to check the robustness and applicability of process. The feasibility of optimized process parameters was validated in 7.5 L fermenter.

Materials and methods

Corn cob chemical composition

Corn cob was provided by Abhyoday Feedstock Suppliers, Jalgaon (M.S.), India. The moisture content was analyzed by heating the samples in an oven at 105 °C until a constant weight was achieved. Air dried corn cob was milled into small particles (3.5 mm × 2.5 mm) using knife mill. Corn cob compositional analysis performed for determination of total extractive, total carbohydrate, ash, and total lignin content (Sluiter et al. 2008a, b, c). The total extractive content of the biomass was determined by refluxing the samples with distilled water for 16 h, followed with 95% ethanol for 16 h in a Soxhlet extractor. Extractive-free samples were hydrolyzed with 72% sulfuric acid at 32 °C for 1 h, followed by hydrolysis with 4% sulfuric acid at 121 °C for 1 h. The ash content analysis was conducted using a furnace at 550 °C till constant weight was achieved. Total carbohydrate content was determined based on total sugar content in the hydrolysate. Sugar concentrations were measured by HPLC (Agilent Technologies, model 1200 series CA, USA), equipped with Aminex HPX-87H column (300 mm × 7.8 mm, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and a refractive index G 1362A detector, an G 1316B column oven and G 1311A pump. Samples were previously filtered through 0.22 µm filter and injected in the column under the following conditions: injection volume, 20 µL; column temperature, 55 °C; 0.005 M H2SO4 as the mobile phase used at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The standards used for sugar qualitative and quantitative analysis were glucose, xylose, and cellobiose (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Sugar analysis was conducted with an injection volume of 20 μL, and data acquisition was performed with Chemstation software. Filtration of the hydrolysate in a vacuum resulted into acid insoluble residue which was regarded as acid insoluble lignin.

Preparation of corn cob hydrolysate

Corn cob was hydrolyzed by following Praj patented pretreatment procedure (Pal et al. 2013). This pretreatment involved corn cob solid of 16–20% w/w (milled using hammer mill), acid mixture (oxalic acid and sulphuric acid) concentration of 0.5–1% w/w, screw speed of 2–4 rpm, reaction temperature of 160–180 °C, and reaction time of 15–20 min. Then, the corn cob slurry and aqueous solution after reaction were discharged and separated in a solid–liquid separation equipment.

Microorganism cultivation and yeast cell immobilization

Candida tropicalis NCIM 3123 was procured from National Collection of Industrial Microorganism (NCIM), Pune, India. The yeast culture was revived and maintained at 4 °C using the following malt extract 3 g/L; xylose 20 g/L; yeast extract 3 g/L; and peptone 5 g/L; (MXYP) agar slants. The microorganism was sub-cultured twice in a month. A loopful of C. tropicalis from 24 h old slant was inoculated into 50 mL of pre-sterilized inoculum medium containing (g/L) xylose 20.0; yeast extract 3.0; malt extract 3.0; and peptone 5.0, pH 6.5 in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask and incubated for 24 h at 30 °C with agitation at 150 rpm. Harvested culture broth was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The cell pellet obtained was washed twice with pre-sterilized distilled water and was used for immobilization studies. The yeast cells were immobilized by encapsulation in calcium alginate beads by use of freezing thawing method (Yewale et al. 2016).

Shake flask fermentation and media optimization study

Basal media (un-optimized media) contain 3 g/L, malt extract; 3 g/L, yeast extract; and 5 g/L, peptone with required xylose concentration from non-detoxified hydrolysate and used as control experiment in xylitol fermentation with 100 mL working volume in 250 mL shake flask, and were sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min. The non-detoxified xylose stream supplemented with different KH2PO4, (NH4)2SO4, urea, MgSO4·7H2O concentration for tests (Table 1) heated at 80 °C for 10 min, and then used as fermentation medium. Batch fermentation was performed in duplicate in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 mL of required pH adjusted corn cob hydrolysate stream with 4–6% w/v xylose.

Table 1.

Plackett–Burman design for screening important variables for xylitol production using calcium alginate immobilized Candida tropicalis

| Run | A: Xylosea | B: Ammonium sulphatea | C: Ureaa | D: KH2POa4 | E: MgSO·47H2Oa | F: Agitation (RPM) | G: Temp (°C) | H: Inoculum beads weight (gm) | J: Initial pH (unit) | K: Dummy 1 | L: Dummy 2 | Xylitol yieldb (g/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 (−1) | 0.2 (+1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.2 (+1) | 0.1 (+1) | 150 (−1) | 40 (+1) | 3 (+1) | 7 (+1) | −1 | −1 | 0.71 ± 0.02 |

| 2 | 6 (+1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.1 (+1) | 0.2 (+1) | 0.05 (−1) | 180(+1) | 40 (+1) | 3 (+1) | 5 (−1) | −1 | −1 | 0.16 ± 0.01 |

| 3 | 4 (−1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.2 (+1) | 0.05 (−1) | 180(+1) | 40 (+1) | 1.5 (−1) | 7 (+1) | 1 | 1 | 0.52 ± 0.02 |

| 4 | 6 (+1) | 0.2 (+1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.05 (−1) | 180(+1) | 30 (−1) | 3 (+1) | 7 (+1) | −1 | 1 | 0.73 ± 0.02 |

| 5 | 4 (−1) | 0.2 (+1) | 0.1 (+1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.1 (+1) | 180(+1) | 40 (+1) | 1.5 (−1) | 5 (−1) | −1 | 1 | 0.49 ± 0.03 |

| 6 | 6 (+1) | 0.2 (+1) | 0.1 (+1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.05 (−1) | 150 (−1) | 40 (+1) | 1.5 (−1) | 7 (+1) | 1 | −1 | 0.79 ± 0.02 |

| 7 | 6 (+1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.1 (+1) | 0.2 (+1) | 0.1 (+1) | 150 (−1) | 30 (−1) | 1.5 (−1) | 7 (+1) | −1 | 1 | 0.77 ± 0.01 |

| 8 | 4 (−1) | 0.2 (+1) | 0.1 (+1) | 0.2 (+1) | 0.05 (−1) | 150 (−1) | 30 (−1) | 3 (+1) | 5 (−1) | 1 | 1 | 0.68 ± 0.03 |

| 9 | 4 (−1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.1 (+1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.1 (+1) | 180(+1) | 30 (−1) | 3 (+1) | 7 (+1) | 1 | −1 | 0.66 ± 0.02 |

| 10 | 6 (+1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.1 (+1) | 150 (−1) | 40 (+1) | 3 (+1) | 5 (−1) | 1 | 1 | 0.74 ± 0.03 |

| 11 | 4 (−1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.05 (−1) | 150 (−1) | 30 (−1) | 1.5 (−1) | 5 (−1) | −1 | −1 | 0.75 ± 0.03 |

| 12 | 6 (+1) | 0.2 (+1) | 0.05 (−1) | 0.2 (+1) | 0.1 (+1) | 180(+1) | 30 (−1) | 1.5 (−1) | 5 (−1) | 1 | −1 | 0.73 ± 0.02 |

aValues in parentheses are coded variables, media components (% w/v)

bMean of duplicate values (SD within 10%)

Plackett–Burman factorial design was used to screen medium components like xylose, ammonium sulphate, urea, KH2PO4, and MgSO4·7H2O, and physical factors like inoculum bead weight, temperature, agitation, and initial pH factors affecting xylitol production. Table 1 shows the experimental design. The effect of each factor is represented by the following equation:

| 1 |

where E(X i) is the concentration effect of tested variable, and and represent xylitol production. Variables (X i) being measured were added to the production medium at high and low concentrations, respectively, and N is the number of experiments performed. Standard error (SE) of the concentration effect was the square root of the variance of an effect and the significant level (p value) of the effect of each concentration was determined using Student’s t test formula:

| 2 |

where E(X i) is the effect of variable X i.

Response surface methodology (RSM) was used to further optimize the significant factors from PB experiments and their interaction effects using Design-Expert Version 9.0.10, Stat-Ease Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, 473 USA) software. The central composite design (CCD) was employed to study the effect of urea, KH2PO4, xylose, and initial pH on xylitol yield by immobilized C. tropicalis in non-detoxified corn cob hydrolysate in 30 trials at 5 levels. The levels for Urea (A), KH2PO4 (B), xylose (C), and initial pH (D) were 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.25; 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.25; 0, 2, 4, 6, 8; and 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, respectively. All experiments were done in duplicate. Statistical analysis of experimental data was also performed using this software. Regression analysis performed gave RSM model equation as follows:

| 3 |

where Y is xylitol yield with predicted response; β 0 is the intercept; β 1, β 2, β 3, and β 4 are the linear coefficients; β 11, β 22, β 33, and β 44 are the squared coefficients; β 12, β 13, β 14, β 23, β 24, and β 34 are the interaction coefficients, and A, B, C, D, A 2, B 2, C 2, D 2, AB, AC, AD, BC, BD, and CD are independent variables.

The combination of different optimized parameters, which showed maximum xylitol yield, was tested experimentally to validate RSM model using numerical optimization. Validation of the model and regression equation was performed by taking the optimum values (w/v) of urea (0.15%); KH2PO4, (0.19%); xylose (5.40); and initial pH (6.7) for the xylitol production in duplicate experiments. The study was carried out in shake flasks of varied volume 0.25 and 0.5 L containing 100 and 200 mL volume of the production medium, respectively.

Bioreactor studies

The possibility of using immobilized cells at large scale for xylitol production was studied in a 7.5 L stirred tank reactor (NBS, USA). The fermenter was conditioned containing 5 L of RSM optimized medium at 80 °C for 10 min. The Fermenter was inoculated with 10 g of wet beads. Fermenter was incubated at temperature 30 °C; agitation, 350 rpm aeration (0.2 vvm), and initial pH 6.65. The samples were drawn at desired intervals and analyzed for xylose, xylitol, glucose, arabinose, ethanol, acetic acid, and pH at different interval. Free cell study was also performed using same conditions in 5 L reactor with inoculating same amount of yeast cells.

Reuse of cells

The non-detoxified hydrolysate was heated at 80 °C for 10 min and supplemented with urea (0.15% w/v); KH2PO4 (0.19% w/v); xylose (5.40% w/v) concentration. pH was adjusted to 6.65 with calcium hydroxide. Duplicate repeated-batch fermentation runs were carried out in 250-mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL of fermentation medium and 1.5 g of immobilized biocatalysts. The flasks were maintained in a rotary shaker at 150 rpm and 30 °C for 96 h. After each run/cycle, the fermented medium was discarded, the solid carrier with immobilized cells was carefully drained and gently washed with water to eliminate all non-adhering yeast cells, and the immobilized biocatalysts were charged with fresh medium. At the end of each cycle, amount of xylitol produced was estimated and the process was carried out using the same immobilized cells for successive cycles.

Analytical methods

Cell density was measured at 640 nm using spectrophotometer (Model U-2900, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The optical density of immobilized cell was estimated after dissolution of 0.5 g of wet bead in 0.1 M sodium citrate solution. A calibration curve was used to co-relate OD measurements to dry cell weight concentration of all samples. Sugar and xylitol concentrations were measured by HPLC (Agilent Technologies, model 1200 series CA, USA), equipped with Aminex HPX-87H column (300 mm × 7.8 mm, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and a refractive index G 1362A detector, an G 1316B column oven, and G 1311A pump. Samples were previously filtered through 0.22 µm filter and injected in the column under the following conditions: injection volume, 20 µL; column temperature, 45 °C; 0.005 M H2SO4 as the mobile phase used at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min.

Results and discussion

Compositional analysis of corn cob and corncob acid hydrolysate

Corn cob used in present study was containing 95–97% (w/w) solid residues and 3–5% (w/w) moisture. Solid part was containing 10% extractives (water and ethanol), 20% lignin (acid insoluble and soluble), 2% protein, 2% ash, 32% cellulose, 31.5% hemicelluloses, and 2.5% acetyls. Corn cob acid hydrolysate obtained after acid hydrolysis was analyzed and found to have the following composition: (% w/w) xylose, 4–6 (% w/w); glucose, 0.5–1.0 (% w/w); arabinose, 0.1–0.3 (% w/w); acetic acid, 0.2–0.6 (% w/w); furfural, 100–300 ppm; 5-(hydroxy methyl) furfural (HMF), 100–500 ppm; and phenolic, 2500–4000 ppm.

Use of media components used in industrial fermentations

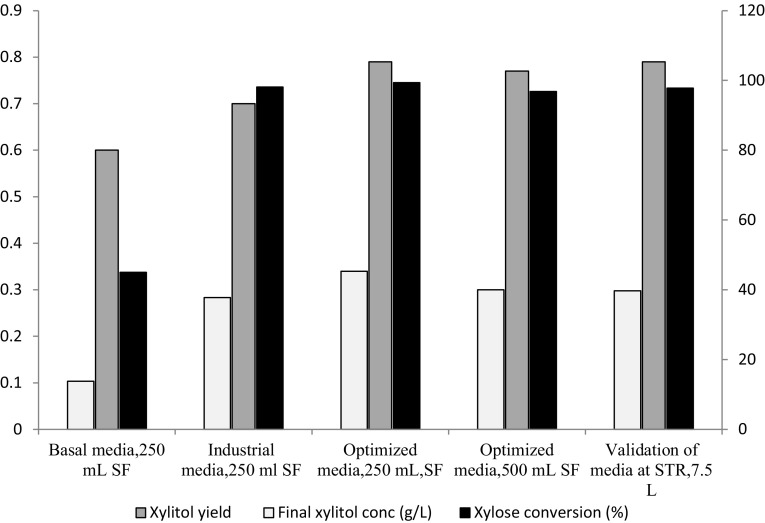

Xylose hydrolysate fermentation in basal media consists of xylose hydrolysate with yeast extract, malt extract, and peptone as nutrients at pH 6.5 (Rajagopalan et al. 2014). The fermentation of immobilized C. tropicalis in this media resulted into 60% xylitol yield and 45% substrate conversion (Fig. 3). As these medium components are expensive, they cannot be applied in industrial processes. In addition, as the basal medium is rich in synthetic nutrients, it is prone to contamination. This will lead to an increase in the operating expenditure due to the requirement of media sterilization and strict sterile fermentation conditions.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of xylose to xylitol bioconversion by C. tropicalis cells immobilized in calcium alginate beads in medium based on corn cob hemicellulosic hydrolysate (working volume 40% v/v, harvest time 72 h. SF shake flask, STR stirred tank reactor)

Media industrialization approach involved replacements of these expensive nutrients with urea as a nutrient. Fermentation with industrial media containing only 500 ppm urea and immobilized C. tropicalis resulted in 70% xylitol yield and 98% substrate conversion (Fig. 3). Thus, the expensive nutrients were removed from basal media with increase in yield and substrate conversion. This was followed by media and process optimization to improve the yield and productivity using the statistical methods (Cao et al. 1994).

Screening of critical variables by Plackett–Burman design

Plackett–Burman design was adopted to select the most significant medium components and fermentation parameters affecting xylitol yield. Among nine variables, which were expected to play a critical role in xylitol production, five of them were media components (xylose, ammonium sulphate, urea, KH2PO4, and MgSO4·7H2O) and four were process parameters (inoculum bead weight, agitation, temperature, and initial pH). A wide variation in xylitol yield (0.16–0.79 g/g) was observed in Plackett–Burman experiments (Table 1).These results showed the importance of optimizing culture variables in attaining higher yields by immobilized microbial cells. Statistical analyses of the responses were performed. The F value of 32.12 implies that model is significant. The value of p < 0.05 indicates that model terms are significant. The regression analysis equation for xylitol yield obtained from Plackett–Burman study is shown below:

| 4 |

Among the tested variables, six factors (urea, KH2PO4, ammonium sulphate, temperature, agitation, and initial pH) had significant effect on xylitol production (p < 0.05). However, for further process optimization, urea, KH2PO4, and initial pH were selected as more significant factors. Urea was preferred instead of ammonium sulphate as inorganic nitrogen source on basis of industrial applicability and availability (Yewale et al. 2016). Although, xylose was not found to be significant in tested narrow range of 4–6% w/v in the Plackett–Burman design, it was selected as critical variable to determine the exact optimum concentration in non-detoxified hydrolysate fermentation. Other significant variables like agitation and temperature were not selected to reduce the number of experiments as major focus was given on industrial media components selection and optimization.

Response surface methodology

Xylose, urea, KH2PO4, and initial pH of media were selected as most important variables affecting xylitol production from Plackett–Burman experiments. Multiple regression analysis was used to analyze the data, and thus, a polynomial equation was derived which is as follows:

| 5 |

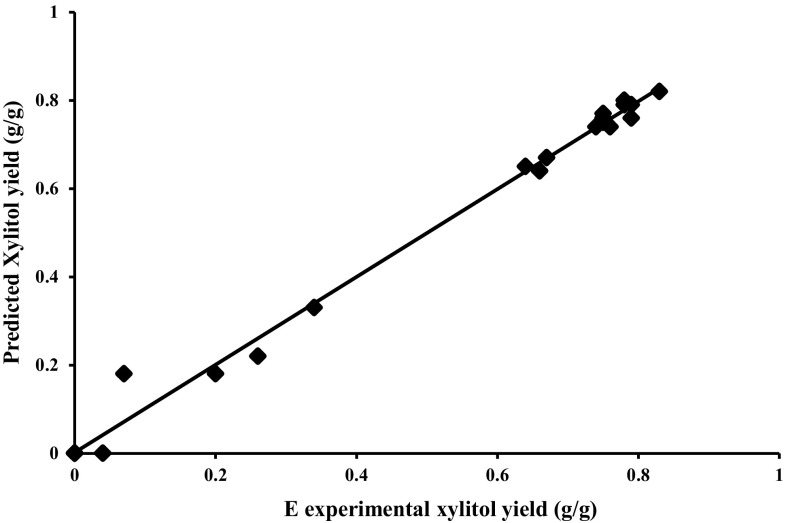

ANOVA analysis shows that F value of 246 indicates that model is significant. The R 2 value (multiple correlation coefficient) closer to 1 (0.9957) denotes better correlation between observed and predicted results (Fig. 1). The predicted R 2 value of 0.9776 was in reasonable agreement with adjusted R 2 value of 0.9916. Values of “Prob > F” less than 0.05 indicate that model terms are significant. In this case, D, CD, C 2, D 2 are significant model terms. Values greater than 0.05 indicate that the model terms are not significant. The “Lack of Fit F value” of 3.16 implies the Lack of Fit is not significant relative to the pure error.

Fig. 1.

Graph of predicted and experimental xylitol yield

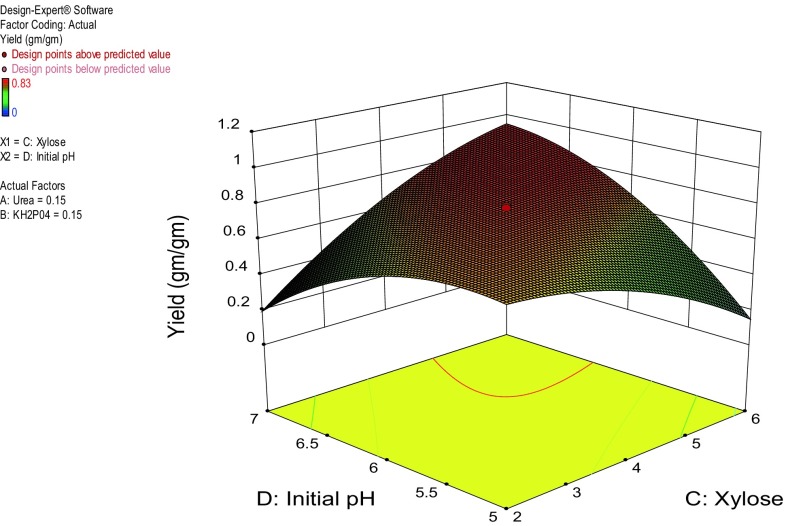

Figure 2 shows three-dimensional plots of the calculated responses from the interaction between pH and xylose. A linear increase in xylitol yields was recorded with increase in xylose concentration and pH which reached up to yields of 0.90 g/g at 6% xylose (‘+1’ level) and initial pH 7.0. Furthermore, the RSM model was validated by numerical optimization. The optimized RSM conditions for xylitol production contain urea 0.15% w/v, KH2PO4 0.19% w/v, xylose 5.40% w/v, and pH 6.65 leading to a yield of 0.79 g/g, whereas the basal media fermentation resulted into xylitol yield of 0.60 g/g only.

Fig. 2.

Response surface curve for xylitol production as a function of pH and xylose concentration

Validation of the optimized conditions

In case of RSM optimized media parameters and physical conditions, xylitol yield 0.79 g/g was obtained which was in close agreement with the predicted xylitol yield, 0.87 g/g. Hence, RSM optimized conditions were validated successfully. Furthermore, xylitol yield was sustainable in shake flask of different volumes (0.25, 0.50 L) by maintaining the 40% ratio of working volume to flask volume, as shown in Fig. 3.

Scale-up of xylitol production

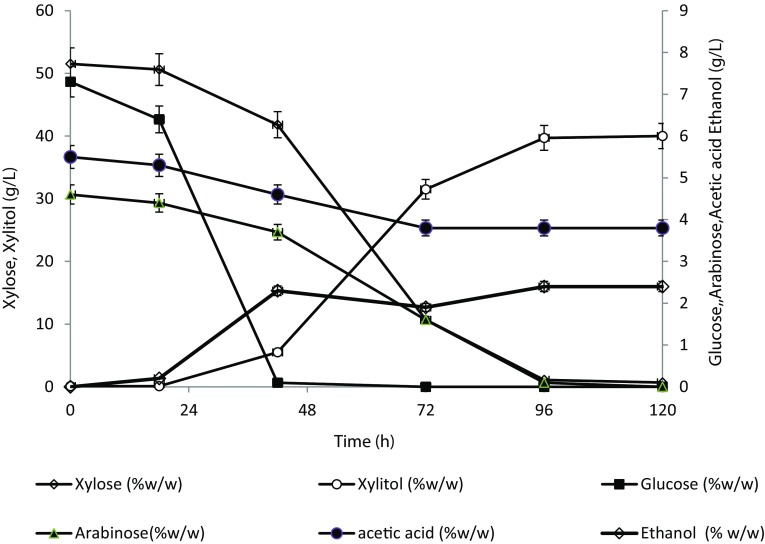

Scale-up study was performed in 7.5 L stirred tank reactor with 5 L working volume containing optimized media composition to check the bead stability, integrity, and xylitol production. It was observed that xylitol concentration increased gradually with the progression of fermentation and reached up to 40 g/L with yield of 0.79 g/g after 96 h, which was comparable to shake flasks and stabilized thereafter without any decrease in yield due to consumption of xylitol by yeast cells (Fig. 4). Fermentation time increased to 96 h (as compared to 72 h for shake flask) in stirred tank reactor as lag phase extended for 20–24 h in STR which could be due to shear stress imparted by impeller and changed mixing conditions. Xylose consumption started after 20 h, and by the end of 96 h, the yeast utilized about 98% of the xylose as a substrate. To assess the potential advantages of the optimized process for xylitol production, xylitol yield obtained in this work was compared with those reported in the literature. Carla and Roberto statistically optimized xylitol fermentation media using rice bran hydrolysate and C. guillermondii (FTI 20037). The significant components observed were rice bran hydrolysates using RSM as optimization methods with xylitol titer 52 g/L, xylitol yield 0.65 g/g and productivity as 0.54 g/L/h (Carla and Roberto 2001). Ling et al. optimized xylitol fermentation media using corn cob hydrolysate using C. tropicalis HDY 02 using PD and RSM methods. The significant nutrients obtained were KH2PO4, yeast extract, ammonium sulphate, and magnesium sulphate with xylitol titer 58 g/L and 0.73 g/g xylitol yield. The xylose stream used in these references was detoxified before fermentation, whereas in present process, corn cob xylose hydrolysate was used without any detoxification (Carla and Roberto 2001; Ling et al. 2011). Xylitol production media optimized using PB and RSM and immobilized C. tropicalis cells resulted into urea, and KH2PO4 as significant nutrients to get xylitol titer of 45 g/L with yield 0.79 g/g and xylitol productivity of 0.47 g/L/h. The immobilized microbial cell gave 0.60, 0.70 g/g yield with 45, 95% substrate conversion in simple basal medium and industrial media, respectively. This performance was enhanced to 0.79 g/g and 98% substrate conversion (Fig. 3) by use of statistical optimization consequently reducing the overall media cost, operating cost, and capital cost. The costly medium components were substituted and optimized by industrial nutrients like urea and KH2PO4, after media screening and statistical optimization.

Fig. 4.

Xylitol production profile of immobilized Candida tropicalis in stirred tank reactor. Error bars represent variation between the duplicate trials

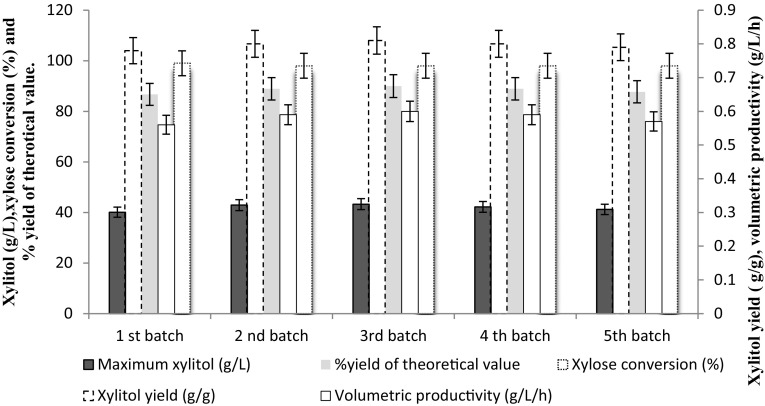

Reuse of immobilized cells

Recycling of alginate-entrapped C. tropicalis cells was studied with optimized media in shake flask. Such reuse was performed five times with no reduction in the xylose consumption, xylitol productivity, and yields. The immobilized yeast produced xylitol with a yield, productivity, and xylose conversion efficiency of more than 0.78 g/g, 0.56 g/L/h, and 98%, respectively, for five successive batches (Fig. 5).The free cell fermentation study in 5 L fermenter shows that C. tropicalis produces 34 g/L xylitol titer with 0.67 g/g yield. Immobilized cell systems are used as an alternative to free cells for increasing the overall process productivity and for minimizing production costs. Immobilized cells exhibit many advantages over free cells including the maintenance of stable, active biocatalysts with high productivity.

Fig. 5.

Performance of immobilization system employed for xylose to xylitol bioconversion by C. tropicalis immobilized in calcium alginate matrix

Conclusions

The present study is the first report to demonstrate the xylitol production in non-detoxified corn cob hydrolysate using freeze dried C. tropicalis yeast cells. Basal media with costly nutrients were successfully replaced with low cost, industrially applicable nutrients with improved yield, and productivity by used of statistical design. Screening and selection criteria resulted into urea, KH2PO4, and initial pH as significant variable. The interactive effects of pH and xylose without detoxification on xylitol yield were found to be significant. Xylitol yield improved from 0.60 to 0.79 g/g in optimized medium with twofold increase in xylose consumption. Thus, the optimized condition with non-detoxified corn cob hydrolysate without sterilization and with low-cost nutrients opens up the scope for industrial application of the process.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the analytical team of Praj Matrix for experimental sample analysis and Siddhartha Pal for providing xylose hydrolysate stream.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13205-017-0700-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Affleck RP (2000) Recovery of xylitol from fermentation of model hemicellulose hydrolysates using membrane technology. M.Sc. thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, Virginia

- Cao NJ, Tang R, Gong CS, Chen LF. The effect of cell density on the production of xylitol from d-xylose by yeast. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1994;45(1):515–519. doi: 10.1007/BF02941826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carla JSM, Roberto IC. Optimization of xylitol production by Candida guillermondii FTI 20037 using response surface methodology. Process Biochem. 2001;36:1119–1124. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(01)00153-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne CP, Blahuta N, Brion F, Gagnon C. A vortex-bowl disk atomizer system for the production of alginate fermentor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;68:681–688. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(20000620)68:6<681::AID-BIT12>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu XB, Zheng ZM, Yu HQ, Wang J, Liang FL, Liu RL. Optimization of medium constituents for a novel lipopeptide production by Bacillus subtilis MO-01 by a response surface method. Process Biochem. 2005;40:3196–3201. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2005.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jirku V, Masák J, Cejková A. Yeast cell attachment: a tool modulating wall composition and resistance to 5-bromo-6-azauracil. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2000;26:808–811. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(00)00175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H, Cheng K, Ge J, Ping W. Statistical optimization of xylitol production from corncob hemicellulose hydrolysate by Candida tropicalis HDY-02. New Biotechnol. 2011;28(6):673–678. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S, Joshi S, Padmanabhan S, Rao R, Kumbhar P (2013) Preparation of lignocellulosic hydrolysate (2053/MUM/2013)

- Pepper T, Olinger PM. Xylitol in sugar free confections. Food Technol. 1988;10:98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Plackett RL, Burman JP. The design of optimum multifactorial experiments. Biometrika. 1946;33:305–325. doi: 10.1093/biomet/33.4.305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Povelainen M (2008) Pentitol phosphate dehydrogenases: discovery, characterization and use in d-arabitol and xylitol production by metabolically engineered Bacillus subtilis. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

- Rajagopalan S, Yewale T, Ingle U, Panchwagh S, Wavikar M, Patil H, Shaikh I, Ahmed F (2014) A process for the preparation of xylitol from natural xylose (1908/MUM/2014). http://ipindiaonline.gov.in/patentsearch/GrantedSearch/viewdoc.aspx?id=81afBGvBut7aK+RCzbjhgw%3d%3d&loc=vsnutRQWHdTHa1EUofPtPQ%3d%3d. Accessed 20 Apr 2017

- Rivas B, Domínguez JM, Domínguez H, Parajó JC. Bioconversion of post hydrolysed auto hydrolysis liquors: an alternative for xylitol production from corn cobs. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2002;31(4):431–438. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(02)00098-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto C, Felipe MGA, Lacis LS, Silva SS, Mancilha IM. Utilisation of sugar cane bagasse hemicellulosic hydrolysate by Candida guillermondii for xylitol production. Bioresour Technol. 1991;36:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0960-8524(91)90234-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter A, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D (2008a) Determination of extractives in biomass. Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP), National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). http://www.nrel.gov/docs/gen/fy08/42619.pdf. Accessed 19 Apr 2017

- Sluiter A, Hames B, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D, Crocker D (2008b) Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. Laboratory Analytical Procedures (LAP), National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). http://www.nrel.gov/docs/gen/fy13/42618.pdf. Accessed 19 Apr 2017

- Sluiter A, Hames B, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D (2008c) Determination of ash in biomass. Laboratory Analytical Procedures (LAP). National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). http://www.nrel.gov/docs/gen/fy08/42622.pdf. Accessed 19 Apr 2017

- Tran LH, Yogo M, Ojima H, Idota O, Kawai K, Suzuki T. The production of xylitol by enzymatic hydrolysis of agricultural wastes. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2004;9:223–228. doi: 10.1007/BF02942297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uhari M, Kontiokari T, Koskela M, Niemelä M. Xylitol chewing gum in prevention of acute otitis media: double blind randomized trial. BMJ. 1996;313:1180–1184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7066.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yewale T, Panchwagh S, Rajagopalan S, Dhamole P, Jain R. Enhanced xylitol production using immobilized Candida tropicalis with non-detoxified corn cob hemicellulosic hydrolysate. 3 Biotech. 2016;6(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0388-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylikahri R. Metabolic and nutritional aspect of xylitol. Adv Food Res. 1979;25:159–180. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2628(08)60237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.