Abstract

Increasing evidence indicates that the dysregulation of miRNAs that act as tumor suppressors or oncogenes is involved in tumorigenesis. However, the role of miR-539 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has not been well investigated. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), proliferation assay, colony formation assay, migration and invasion assays, western blotting, and xenograft tumor growth models were performed to assess the expression levels and functions of miR-539 in HCC. Luciferase reporter assays, qRT-PCR, western blotting, and immunohistochemistry were used to identify and verify the targets of miR-539. miR-539 was significantly downregulated in HCC cell lines and tissue samples. Ectopic expression of miR-539 inhibited cell viability, proliferation, migration, and invasion in vitro and suppressed xenograft tumor growth in vivo. Fascin homologue 1 (FSCN1) was verified as a direct target of miR-539, and overexpression of FSCN1 promoted HCC cell migration and invasion. miR-539 acts as a novel tumor suppressor in the development and progression of HCC by targeting FSCN1, providing new insight into the mechanisms of HCC carcinogenesis and suggesting that miR-539 may be a therapeutic target.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, miR-539, fascin homologue 1, migration, invasion

Introduction

Primary liver cancer, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), is the sixth most common and aggressive malignancy worldwide, accounting for over 800,000 deaths per year (1,2). In China, the mortality rate of HCC is the second highest, and the 5-year survival rate is below 5% (3). The major cause of mortality in HCC patients is tumor cell invasion and metastasis, which is a complex process that involves changes in the extracellular matrix, leading to translocation from the primary tumor to distant organs and growth at new sites. Multiple reports have shown that various signaling pathways are involved in tumor metastasis, but the details of the molecular mechanisms underlying tumor invasion and metastasis remain largely unclear. Therefore, it is crucial to elucidate the mechanisms of tumor metastasis and to develop a novel strategy for HCC treatment.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of endogenous noncoding RNAs that are 21–23 nucleotides in length (in mammals). They are evolutionarily conserved and bind primarily to complementary sequences in the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of their target mRNAs, inhibiting translation or destabilizing the mRNAs (4). miRNAs can function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors, and miRNA dysfunction is involved in many biological processes, including the development and progression of various human cancers (4,5). The aberrant expression of specific miRNAs is directly implicated in tumorigenesis, including processes of growth, apoptosis, and metastasis (6,7). For example, miR-199a suppresses tumorigenicity and multidrug resistance of ovarian cancer-initiating cells (8). Thus, miRNAs act as potentially important tumor hallmarks, and their deregulation has been studied to identify tools for early diagnosis, prognosis, monitoring, and treatment (9,10). However, the functions and mechanisms of miRNAs involved in HCC metastasis are largely unknown.

In this study, we examined the effect of miR-539 on HCC cells to determine its potential contribution to HCC migration and invasion. We evaluated the expression of miR-539 in HCC cell lines and clinical specimens. Additionally, we investigated the functional role of miR-539 in the migration and invasion of HCC cell lines and the contribution of miR-539 to HCC cancer malignancy and the underlying molecular mechanisms. Our findings elucidated important roles of miR-539 in HCC and suggested novel therapeutic strategies for HCC treatment.

Materials and methods

Human tissue samples

The HCC samples and corresponding adjacent non-tumorous liver tissues were obtained from 30 patients with primary HCC who underwent surgery at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University (Xi'an, China) from July 2012 to June 2014. The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients were independently determined by two experienced pathologists. All tissue samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. None of the patients recruited in this study had undergone preoperative chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or other therapy.

Lentiviral production, plasmid construction, and transfection

Viral vectors containing the miR-539 (GenBank ID: 664612) construct and the green fluorescent protein (GFP) construct were purchased from Takara (Shiga, Japan). The miR-539 sequence was sub-cloned into the pLVX-IRES-Hyg vector (Takara) to generate pLV-miR-539. The viral particles were harvested 48 h after transfection of pLV-miR-539 into HEK293T cells using the Lenti-HT Packaging Mix (Takara). HCCLM3 and SK-HEP1 cells were infected with the harvested recombinant lentivirus in the presence of 6 µg/ml Polybrene (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The empty pLV-GFP vector encoding GFP was used as the control (Fig. 1). The viral particles were harvested as previously described (11) and used in all subsequent studies.

Figure 1.

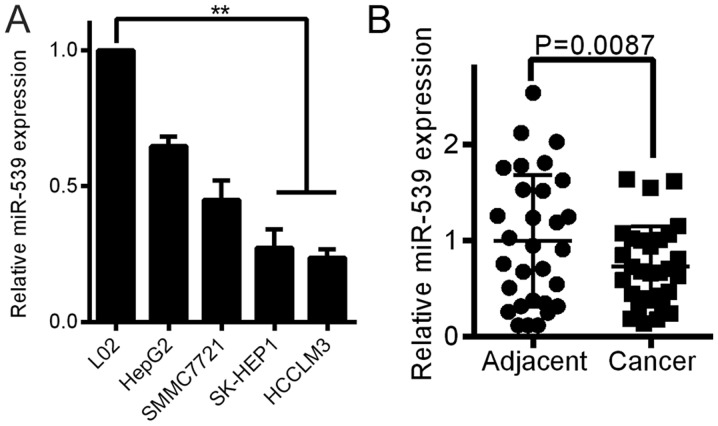

miR-539 is downregulated in HCC cells and tissues. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of miR-539 expression in normal liver cells (L02) and the HCC cell lines HepG2, SK-HEP1, HCCLM3, and SMMC-7721. (B) miR-539 expression in thirty paired HCC tissues and their adjacent normal tissues. Average miR-539 expression was normalized to U6 expression. Bars represent the mean of three independent experiments. **P<0.01.

The full-length 3′-UTR of the FSCN1 gene containing the putative miR-539 binding sites was amplified by PCR and was inserted into the pGL3 vector under the control of the CMV promoter (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The coding sequences of FSCN1 were amplified by PCR and cloned into the pCDNA3.1(+) vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to generate pCDNA-FSCN1. The primer sequences used to amplify the target genes are listed in Table I. The correct insertion of the PCR-amplified sequences was confirmed by sequencing. The plasmid was transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Table I.

Primer sequences.

| Primer sequences (5′-3′) | Length (bp) | |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH-F | TCATGGGTGTGAACCATGAGAA | 146 |

| GAPDH-R | GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG | |

| FSCN1-F | CACAGGCAAATACTGGACGGT | 101 |

| FSCN1-R | CCACCTTGTTATAGTCGCAGAAC | |

| miR-539-F | GGAGAAATTATCCTTGGTGTG | / |

| U6-F | ATTGGAACGATACAGAGAAGATT | / |

| FSCN1-F | GGAATTCATGACCGCCAACGGCACAGCCGA | 1497 |

| FSCN1-R | CCCTCGAGTTAGTACTCCCAGAGCGAGGCGGG | |

| FSCN1-wtUTR-F | GCTCTAGATGCTAACCCCTTCTCCGCCAGGT | 491 |

| FSCN1-wtUTR-R | GCTCTAGAAAGGGTCAGTCCTAGCCCACCCGA | |

| FSCN1-mutUTR-F | ACCTCAGATGGCTAAGTCACGCAGACACATGGAAGCG | 491 |

| FSCN1-mutUTR-R | CGCTTCCATGTGTCTGCGTGACTTAGCCATCTGAGGT |

RNA extraction and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA from cultured cells and frozen tissues was extracted using the RNAiso reagent (Takara) according to manufacturer's instruction. To measure the miR-539 levels, we used a miRNA reverse transcription kit (Invitrogen) and SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) to obtain the cDNA using qRT-PCR. Aliquots (1 µg) of RNA were reverse transcribed to cDNA (20 µl) with oligo(dT) and M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. One-fifth of the resulting cDNA was used as a template for PCR using a SYBR Green PCR kit (Takara) in a LightCycler 480 Real-time PCR System (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as an internal control for each mRNA expression experiment. U6 was used for miRNA normalization. The primer sequences for the target genes are listed in Table I. The cycling conditions were as follows: an initial 10 min of pre-denaturation at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 20 sec, and 72°C for 15 sec. The specificity of the amplification products was confirmed by melting curve analysis. Each RT reaction was run in triplicate. The relative quantification of miR-539 or FSCN1 was performed using the 2−∆∆Ct method to analyze the qRT-PCR data (12).

Cell proliferation studies

Cells were plated in 96-well plates at 2×103 per well. At the indicated time points, 100 µl of 3-(4–5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, 0.5 mg/ml, Roche Diagnostics) was added to each well, and the cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C, followed by removal of the culture medium and addition of 150 µl dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma) to dissolve the formazan crystals. The OD value at 450 nm was then determined and used to construct a growth curve with time to assess cell proliferation. Each experiment was repeated at least thrice.

Colony formation assay

For the soft-agar assay, 2,000 cells were suspended in complete medium containing 0.6% agar (Sigma) and then added on top of a layer of complete medium containing 1% agar in 6-well plates. Colonies were counted under an inverted microscope after 20 days. The colonies were counted in 10 randomly chosen microscope fields.

Wound healing assay

To further investigate cell migration, we used wound healing assays as previously described (13). Cells (2×105) were seeded in 6-well plates, incubated overnight, and then infected or transfected with a test vector or vehicle. At 90% confluency, the cell monolayer was scratched with a sterile 200-µl pipette tip. Then, the plate was washed with PBS 5–6 times to remove the suspended cells, and the cells were maintained in DMEM containing 1% FBS. Images were taken at 0 and 24 h along the scrape line under a microscope to observe the migrated cells and wound healing, and the cells in three wells from each group were quantified. The results are expressed as the relative scratch width based on the distance migrated relative to the original scratched distance. ImageJ Plus was used to quantify the images of the wound healing assays.

Transwell cell migration and invasion assay

As previously described (14), cell migration and invasion were assayed using Transwells with an 8 µm pore size (Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA). The Transwells were placed into 24-well plates. The following day, the medium was removed, and 100 µl fresh medium was added to the upper chambers coated without or with Matrigel (BD Biosciences) in each insert. Then, 500 µl DMEM with 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. After incubation for 24–48 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator, the cells on the upper surface were removed with a cotton swab, and the cells that migrated or invaded to the bottom side of the membrane were fixed with 95% absolute alcohol and stained with crystal violet for 20 min at room temperature. Four random fields of each membrane were imaged under an inverted microscope (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) at ×100 magnification, and the cells were counted for statistical analysis. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Bioinformatics and dual luciferase reporter gene assay

Three generally accepted online bioinformatics programs, TargetScan, RNAhybrid, and microRNA.org, were used to predict the interactions between miR-539 and target mRNAs. The predicted candidates were further investigated. Luciferase reporter assays were performed using a construct that contained the regions of interest that were sub-cloned into the XbaI restriction site of the luciferase reporter vector pGL3 Basic Vector (Promega). The PCR products were amplified from the full-length 3′-UTR of FSCN1 using the primers listed in Table I. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) to alter the miR-539 binding site sequence in the 3′-UTR FSCN1-amplified PCR product. For luciferase assays, SK-HEP1 cells were seeded at 1.0×105/well in 24-well plates, cultured until they reached 70% confluence, and co-transfected with LV-miR-con or LV-miR-539; pGL3-control (400 ng; Promega), pGL3-FSCN1-WT (400 ng) or pGL3-FSCN1-Mut; and pRL-TK (50 ng, Promega) using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. Cells were lysed using cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Boston, MA, USA), and luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Three independent experiments were performed, and the data are presented as the mean ± SD.

Eukaryotic expression vector construction

To construct a plasmid that expresses FSCN1 in cells, we cloned the open reading frame (ORF) of FSCN1 into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1(+) (Invitrogen) using the primers in Table I. The constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

Preparation of cell extracts and western blot analysis

Western blot analyses were performed as previously described (15). Protein lysates were prepared on ice in RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP40 and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate] for 30 min with freshly added 0.1 mg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 1 mg/ml aprotinin. The supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Aliquots of cell extracts containing 20–50 µg of total protein were resolved using 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a 0.45 mm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA). Membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T [10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20] for 2 h at room temperature (RT) and then incubated for 4 h at RT in Blotto A containing a 1:1000 dilution of rabbit anti-FSCN1 and anti-GAPDH monoclonal antibodies. After a wash in TBS-T buffer (5 min, RT), the membranes were incubated for 1 h at RT in Blotto A containing a 1:10,000 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). After a wash in TBS-T, the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) luminol reagent (Pierce) was used to develop the membrane according to the manufacturer's recommendation. GAPDH was used as a loading control. All procedures were performed three times.

Tumor studies in vivo

Athymic nude and BALB/c mice were obtained from the Shanghai Experimental Animal Center (Shanghai, China) and maintained according to the Animal Research Committee's guidelines at Xi'an Jiaotong University. Briefly, a total of 2×106 SK-HEP1 cells were injected into the right leg of each mouse (seven animals for each treatment) and then monitored every other day for tumor growth. When the tumors grew to 40–50 mm3, the animals were randomly divided into two treatment groups. Each mouse was treated with LV-miR-con (100 µl, 2×108 TU/ml) or LV-miR-539 (100 µl, 2×108 TU/ml) via intratumoral injection. All treatments were administered every other day for a total of five doses. Tumor growth was monitored by measuring perpendicular tumor diameters using an electronic digital caliper. Tumor volumes were calculated by the following formula: tumor size=ab2/2, where a is the larger and b is the smaller of the two dimensions. The tumor-bearing mice were sacrificed 24 days after injection, and the tumors were removed, weighed, and examined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining assays.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining

Solid tumors were removed from the sacrificed mice and were fixed with 4% formaldehyde. Paraffin-embedded tumor tissues were sectioned to 5-µm thickness and mounted on positively charged microscope slides, and 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) was used for antigen retrieval. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating the slides in methanol containing 3% hydrogen peroxide, and the slides were then washed in PBS for 6 min. Next, the sections were incubated for 2 h at RT with normal goat serum and subsequently incubated at 4°C overnight with a primary antibody (Abcam: 1:100, Ki67). Then, the sections were rinsed with PBS and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-linked goat anti-rabbit antibody, followed by reaction with Mayer's hematoxylin. Ki-67 was determined as the ratio of the number of cells positive for brown staining to the total number of cells in a given field of view at ×400 magnification. Five fields of view were analyzed per section.

Statistical analyses

The results represent the average of three experiments, and the data are presented as the mean ± SD. Each experiment was performed at least three times unless otherwise specified. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired Student's t-test, and a value of P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

miR-539 is downregulated in HCC cell lines and tissue samples

QRT-PCR analyses were performed to determine the expression level of miR-539 in 4 HCC cell lines and the normal liver cell line L02. The levels of miR-539 were downregulated in all HCC cell lines compared with the miR-539 level in the L02 cells (Fig. 1A). The miR-539 expression was also measured in 30 freshly frozen HCC and adjacent normal tissue samples. The expression of miR-539 was significantly decreased in 19 HCC tissues compared to the expression in the adjacent tissues (Fig. 1B, P<0.01). Five HCC tissues were expressed to the high level of the adjacent tissues, while 6 HCC tissues were the same with the adjacent tissues.

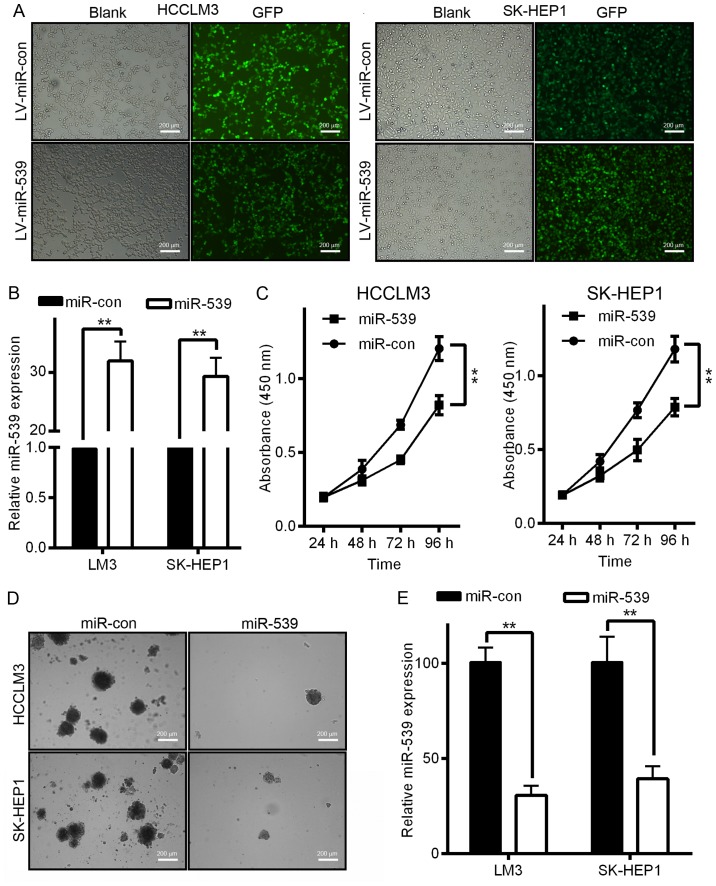

miR-539 inhibits HCC cell growth and proliferation in vitro

The downregulation of miR-539 in both HCC tissues and HCC cell lines suggested that miR-539 may play a role in HCC tumorigenesis. To investigate the biological function of miR-539 in the development and progression of HCC, we performed MTT and soft-agar assays after the infection of HCC cells with LV-miR-539 or LV-miR-con. We first generated LV-miR-539 or LV-miR-con and then used these constructs to infect HCCLM3 and SK-HEP1 cells. The increased miR-539 expression was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 2B). As shown in Fig. 2C, HCCLM3 and SK-HEP1 cells infected with LV-miR-539 displayed significant growth inhibition compared to that of cells infected with LV-miR-con (P<0.01). Moreover, cells infected with LV-miR-539 formed fewer and smaller colonies compared with cells infected with LV-miR-con in an anchorage-independent manner (Fig. 2D and E, P<0.05).

Figure 2.

miR-539 inhibits HCC cell growth and proliferation in vitro. (A) Fluorescence images of GFP in HCCLM3 and SK-HEP1 cells infected with lentiviruses encoding both GFP and miR-539. Strong GFP expression was detected in the lentiviral-infected cells. Scale bar, 200 µm. (B) The expression of miR-539 was upregulated in the cells infected with LV-miR-539. miR-539 levels were measured by qRT-PCR. (C) Cell viability was detected by MTT assays. **P<0.01. (D) Cell anchorage-independent proliferation was detected by soft-agar assays. (E) The count number of colonies is indicated. Data are presented as the mean ± SD; P-values was calculated with Student's t-test.

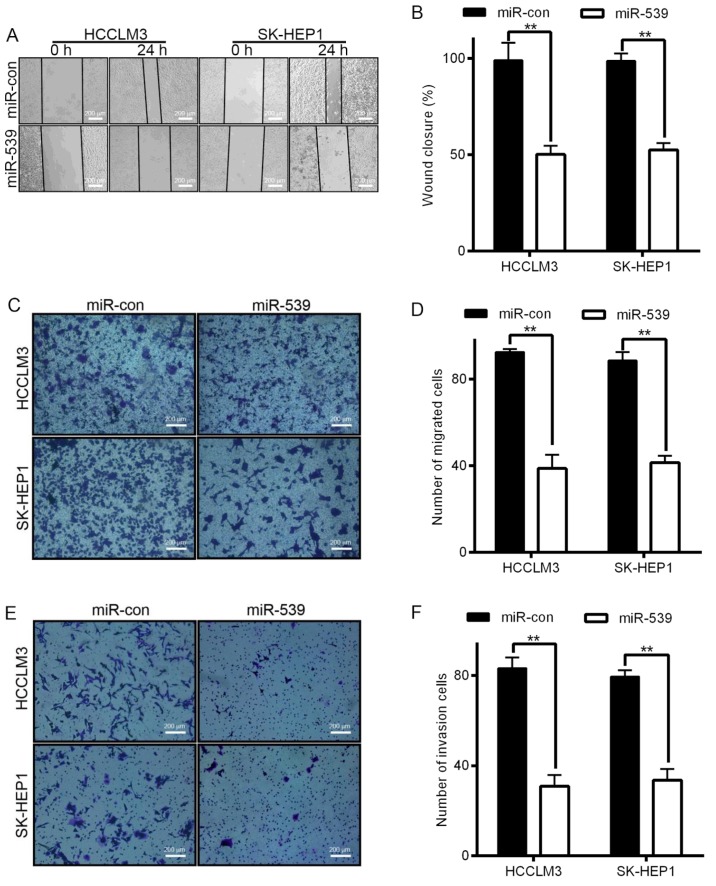

miR-539 inhibits HCC cell migration and invasion in vitro

Invasion and migration through the basement membrane is a characteristic property of metastatic cancer cells. We used two different approaches to assess the role of miR-539 in the migration of HCCLM3 and SK-HEP1 cells. The wound healing assays showed that the migratory ability of HCCLM3 and SK-HEP1 cells infected with LV-miR-539 was much weaker than that of cells transfected with miR controls (Fig. 3A and B). Transwell migration assays also demonstrated that the overexpression of LV-miR-539 significantly suppressed the migratory ability of HCCLM3 and SK-HEP1 cells (Fig. 3C and D, P<0.01). In addition, Transwell invasion assays indicated that invasion was inhibited by infection with LV-miR-539 (Fig. 3E and F, P<0.05). These results, taken together, clearly demonstrate that overexpression of miR-539 markedly reduces the migration and invasion of HCC cancer cells.

Figure 3.

Ectopic expression of miR-539 in HCCLM3 and SK-HEP1 cells inhibits cell migration and invasion in vitro. (A and B) Cell migration was detected by wound healing assays. (C and D) HCCLM3 and SK-HEP1 cells were loaded in the top well of Transwell inserts for cell migration assays. Migrating cells were stained with crystal violet, visualized under a phase-contrast microscope, and photographed. **P<0.01. (E and F) Ectopic expression of miR-539 impeded cell invasion in HCCLM3 and SK-HEP1 cells as determined by Transwell invasion assays. Scale bar indicates 200 µm. Data are presented as the mean ± SD; P-values was calculated with Student's t-test.

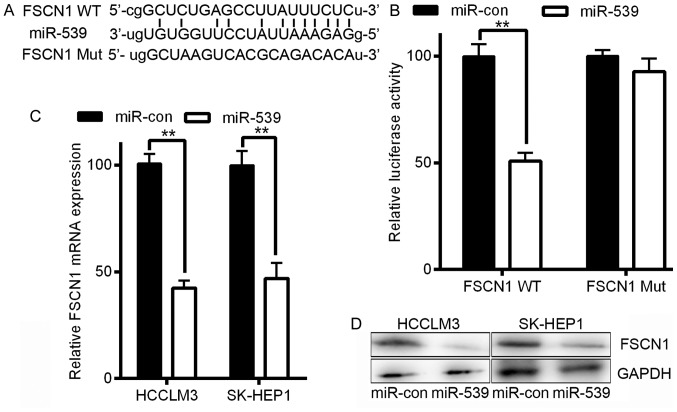

FSCN1 is a direct target of miR-539

Next, we explored the underlying molecular mechanism of the anti-tumorigenic effects of miR-539 in HCC cells. Because miRNAs primarily mediate their biological functions in animal cells by altering the expression of target genes, we performed a bioinformatics search with publicly available databases (TargetScan, RNAhybrid, and microRNA.org) for putative mRNA targets of miRNAs that exhibited anti-tumor properties. Fascin homologue 1 (FSCN1) was identified as a potential target as it contains one potential miR-539 binding site within its 3′-UTR (Fig. 4A). FSCN1 is a 55 kDa actin-binding protein that is an important regulator of the maintenance and stability of filamentous actin and plays a crucial role in the regulation of cell adhesion, migration, and invasion (16,17).

Figure 4.

FSCN1 is a direct miR-539 target. (A) FSCN1 3′-UTRs contains one predicted miR-539 binding site. In the figure, the alignment of the seed region of miR-539 with the FSCN1 3′-UTR is shown. The sites mutated by target mutagenesis are indicated below. (B) Relative luciferase activity was detected by luciferase reporter assays. (C) Quantification of FSCN1 mRNA expression by qRT-PCR. D) FSCN1 protein expression was assessed by western blotting after miR-539 overexpression. **P<0.01. Data are presented as the mean ± SD; P-values was calculated with Student's t-test.

Additionally, FSCN1 has been reported to regulate the migration and invasion of HCC (18). To assess the potential regulation of FSCN1 by miR-539 via this putative binding site, we constructed a reporter vector consisting of the luciferase coding sequence followed by the 3′-UTR of FSCN1. Either the wild-type (pGL3-FSCN1-WT) or a mutated sequence (pGL3-FSCN1-Mut) with the seed region sites was cloned into the modified pGL3 vector (Fig. 4B). Co-transfection experiments showed that miR-539 significantly decreased the luciferase activity of the construct containing the wild-type 3′-UTR sequence in HCCLM3 cells (P<0.01, Fig. 4B), but this decreased activity was not observed in the pGL3-FSCN1-Mut-transfected cells (Fig. 4B). Our data thus demonstrated that FSCN1 is a direct target of miR-539. To further confirm that miR-539 targets FSCN1, we transfected LV-miR-539 or LV-miR-con into HCCLM3 and SK-HEP1 cells. Infection with miR-539 resulted in a significant reduction in FSCN1 mRNA and protein expression as measured by qRT-PCR and western blotting, respectively, in HCCLM3 and SK-HEP1 cells (P<0.01, Fig. 4C and D). Taken together, these results indicate that in HCC cells, FSCN1 is a direct target gene of miR-539, and this regulation requires the miR-539 binding sequence in the 3′-UTR.

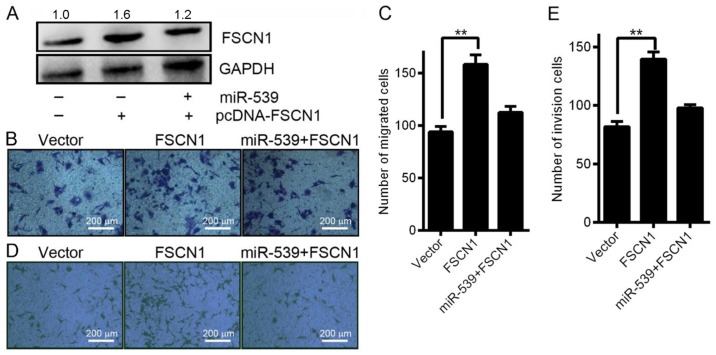

Restoring FSCN1 expression reverses the effect of miR-539 on HCC cell migration and invasion

FSCN1 has been reported to play a critical role in the migration and invasion of HCC (18). To confirm that miR-539 regulates FSCN1, we co-transfected SK-HEP1 cells with LV-miR-539 and pcDNA-FSCN1 to perform a rescue experiment. As shown in Fig. 5A, western blotting analysis indicated that simultaneous transfection of SK-HEP1 cells with miR-539 and pcDNA-FSCN1 reduced the ability of miR-539 to downregulate FSCN1 protein expression. Consistent with this result, the Transwell migration assays revealed that co-transfection of pcDNA-FSCN1 significantly reduced the ability of the miR-539 to inhibit cell migration at 24 h after transfection (Fig. 5B and C). Additionally, the Transwell invasion assays showed that co-transfection of pcDNA-FSCN1 abolished the increased cell invasion promoted by infection by LV-miR-539 at 24 h (Fig. 5D and E). Overall, the results indicate that miR-539 suppresses HCC cell invasion and migration by regulating FSCN1.

Figure 5.

Restoring FSCN1 expression reverses the effect of miR-539 on HCC cell migration and invasion. SK-HEP1 cells were transfected with pcDNA3-FSCN1 alone, pcDNA3-FSCN1 plus LV-miR-539, and the corresponding pcDNA3 vector as the negative control. (A) Detection of FSCN1 protein expression by western blot analysis. (B and C) Effects of pcDNA-FSCN1 on miR-539-infected SK-HEP1 cells were examined by Transwell migration assays. Scale bar indicates 200 µm. The graph shows the mean ± SD, and **P<0.01, as determined by Student's t-test, for the test groups versus the vector control. (D and E) Transwell invasion assays of LV-miR-539-infected SK-HEP1 cells co-transfected with pcDNA-FSCN1. Scale bar indicates 200 µm. Data are presented as the mean ± SD; P-values was calculated with Student's t-test.

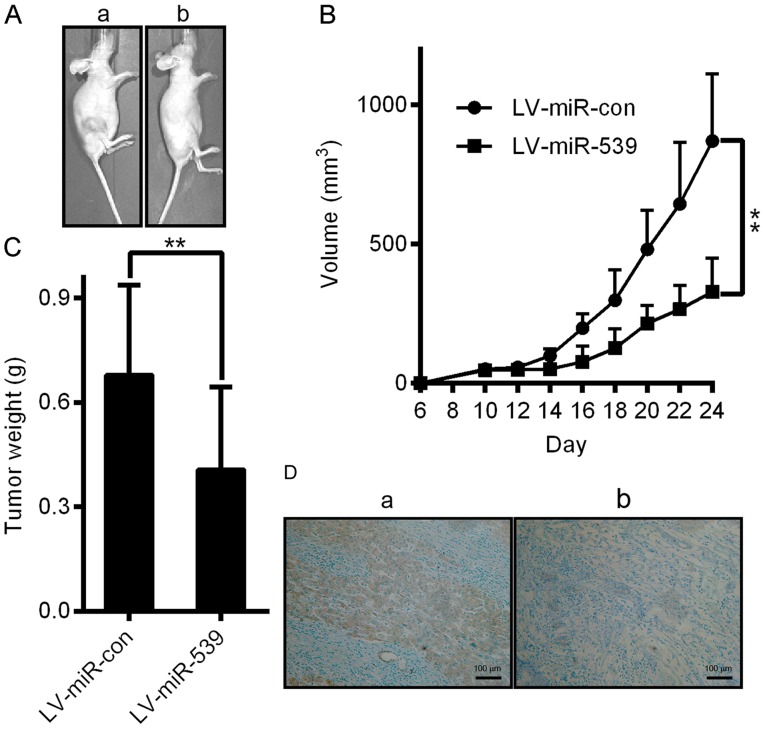

miR-539 inhibits HCC xenograft tumor growth in vivo

To further confirm the growth-attenuating effect of miR-539 on HCC, we performed a xenograft tumor growth assay. Xenograft tumor growth models were established as described in the methods section. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, tumors grew at a slower rate and had smaller volumes in the miR-539-overexpressing group than those of the miR-con group (P<0.05). The average tumor weight in the miR-539-overexpressing group was also significantly lower than that of the control group (0.41±0.09 g vs. 0.68±0.10 g; Fig. 6C, P<0.05). We further performed IHC staining for Ki67 in the tumors. Compared with the miR-con control, miR-539 overexpression suppressed proliferative activity, as indicated by the percentage of cells positive for Ki67 staining (Fig. 6D). Our results revealed that miR-539 attenuated the proliferation of HCC cells in vivo. Thus, this study demonstrates that miR-539 plays a tumor suppressive role in HCC.

Figure 6.

Suppression of tumor growth by LV-miR-539 in vivo. (A and B) Representative images of tumors formed and the growth curves of tumor volume. a, LV-miR-con group. b, LV-miR-539 group. (C) The total weight of the HCC tumors in each group. (D) Representative images of IHC sections by Ki67 staining from mice. a, LV-miR-con group. b, LV-miR-539 group. Data are presented as the mean ± SD; P-values was calculated with Student's t-test.

Discussion

There are several miRNAs with potential roles in cancer development, and we selected miR-539 as the focus of this study due to its tumor suppressor role in osteosarcoma cancer (19) and its unclear roles in HCC. miR-539 is present in the miRNA-rich intragenic region of mouse chromosome 12 [NC_000078.6 (109728129 to 109728202)] between Rian (RNA imprinted and accumulated in nucleus) and Mirg (miRNA-containing gene). There are few verified targets of miR-539, although miR-539 has been shown to inhibit migration and invasion in several types of tumors, including thyroid cancer (20), prostate cancer (21), and osteosarcoma (19). Recently, Zhang et al (21) showed that ectopic overexpression of miR-539 drastically inhibited SPAG5 expression and prostate cancer cell proliferation and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, Zhu et al reported miR-539 was downregulated in HCC tissues and cells, and suppresses tumor growth and tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo. miR-539 overcomes arsenic trioxide resistance in HCC (22). There may be different effects of miR-539 on different cellular processes involved in tumor development, so the roles of miR-539 are still poorly understood.

FSCN1, a 55 kDa actin-binding protein, regulates the maintenance and stability of filamentous actin and plays a crucial role in the regulation of cell adhesion, migration, and invasion (16,17). The overexpression of FSCN1 was associated with aggressive clinical course, poor prognosis, and decreased survival in various cancers, including HCC (18,23), indicating that FSCN1 may play a central role in tumorigenesis. The tumorigenic function of FSCN1 may be conferred by its invasive properties in cancer cells (24). The knockdown of FSCN1 expression reduced the proliferation and metastasis of GC cells, and higher expression of FSCN1 was correlated with more advanced cancer stages and inversely correlated with survival rates in gastric adenocarcinomas (25). A previous study identified FSCN1 as a target of miR-145 in bladder cancer cells (26), but the clinical relevance of FSCN1 in HCC remains unknown.

HCC is characterized by rapid growth and relentless invasion. Invasiveness and metastasis, the two leading causes of cancer mortalities, are especially pronounced in HCC, which shows strikingly high invasive and metastatic potential (27). We highlighted the therapeutic potential of miR-539 in HCC by identifying miR-539 as a tumor suppressor that attenuates the proliferation and invasion of HCC cells both in vitro and in vivo and inhibited growth and invasion of HCC cells in a nude mouse model. To identify novel downstream targets of miR-539, we used the TargetScan, RNAhybrid, and microRNA.org databases to perform screening experiments. From several candidates, FSCN1 was selected for further experiments due to the crucial roles of FSCN1 in tumor migration and invasion. Several pieces of evidence suggest that FSCN1 is a direct downstream target of miR-539. First, FSCN1 contains highly conserved sequences at the 3′-UTR that are complementary to the miR-539 seed sequence. Second, we observed that levels of miR-539 were substantially reduced in HCC samples compared to adjacent tissues. The present study additionally shed new light on the correlation between miR-539 and FSCN1 in HCC. Our results suggest that miR-539 and FSCN1 both play important roles in HCC invasion.

Our present study represents the first comprehensive analysis of miR-539 in HCC. We selected miR-539 as a target molecule based on miRNA profiling and then identified miR-539 as a tumor suppressor that can attenuate the proliferation and invasion of HCC in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, we identified FSCN1 as a direct functional target of miR-539, which expanding our understanding of the players and mechanisms underlying HCC progression.

Although several studies have reported the regulation of FSCN1 by miRNAs in many malignant tumors (26,28,29), to the best of our knowledge, no study has identified FSCN1 as a direct target of miR-539 in HCC. In this study, we confirmed that miR-539 inhibits the expression of FSCN1 and directly targets the 3′-UTR of FSCN1 in HCC cells. Furthermore, the simultaneous re-expression of FSCN1 compromised the miR-539 supression of cell migration and invasion almost completely in miR-539-transfected SK-HEP1 cells, which indicated that the repression of FSCN1 is necessary for miR-539 to inhibit the migration and invasion of HCC cells. Therefore, FSCN1 is an important downstream target of miR-539 in the regulation of HCC migration and invasion.

In brief, our study showed that miR-539 is primarily downregulated in HCC samples and cell lines and that miR-539 expression and FSCN1 expression are strongly negatively correlated in HCC. In addition, we provided evidence that miR-539 inhibits cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in HCC via targeting FSCN1 directly. Therefore, restoring miR-539 expression should be explored as a potential therapeutic strategy for treatment of HCC.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81572734), the Scientific and Technological Development Research Project Foundation by Shaanxi Province (2016SF-121) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities in Xi'an Jiaotong University (no. 2013jdhz33).

References

- 1.DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, Alteri R, Robbins AS, Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:252–271. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hao K, Luk JM, Lee NP, Mao M, Zhang C, Ferguson MD, Lamb J, Dai H, Ng IO, Sham PC, et al. Predicting prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma after curative surgery with common clinicopathologic parameters. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:389. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng CJ, Bahal R, Babar IA, Pincus Z, Barrera F, Liu C, Svoronos A, Braddock DT, Glazer PM, Engelman DM, et al. MicroRNA silencing for cancer therapy targeted to the tumour microenvironment. Nature. 2015;518:107–110. doi: 10.1038/nature13905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee YS, Dutta A. MicroRNAs in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:199–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White NM, Fatoohi E, Metias M, Jung K, Stephan C, Yousef GM. Metastamirs: A stepping stone towards improved cancer management. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:75–84. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen R, Alvero AB, Silasi DA, Kelly MG, Fest S, Visintin I, Leiser A, Schwartz PE, Rutherford T, Mor G. Regulation of IKKbeta by miR-199a affects NF-kappaB activity in ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:4712–4723. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li ZZ, Shen LF, Li YY, Chen P, Chen LZ. Clinical utility of microRNA-378 as early diagnostic biomarker of human cancers: A meta-analysis of diagnostic test. Oncotarget. 2016;7:58569–58578. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Leeuw DC, Verhagen HJ, Denkers F, Kavelaars FG, Valk PJ, Schuurhuis GJ, Ossenkoppele GJ, Smit L. MicroRNA-551b is highly expressed in hematopoietic stem cells and a biomarker for relapse and poor prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30:742–746. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart SA, Dykxhoorn DM, Palliser D, Mizuno H, Yu EY, An DS, Sabatini DM, Chen IS, Hahn WC, Sharp PA, et al. Lentivirus-delivered stable gene silencing by RNAi in primary cells. RNA. 2003;9:493–501. doi: 10.1261/rna.2192803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan W, Chang Y, Li R, Xu Q, Lei J, Yin C, Li T, Wu Y, Ma Q, Li X. Curcumin inhibits hypoxia inducible factor-1α-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:2505–2510. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lei J, Fan L, Wei G, Chen X, Duan W, Xu Q, Sheng W, Wang K, Li X. Gli-1 is crucial for hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasion of breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:3119–3126. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2948-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X, Ma Q, Xu Q, Liu H, Lei J, Duan W, Bhat K, Wang F, Wu E, Wang Z. SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling induces pancreatic cancer cell invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in vitro through non-canonical activation of Hedgehog pathway. Cancer Lett. 2012;322:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayo A, Parsons M. Fascin: A key regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1614–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams JC. Roles of fascin in cell adhesion and motility. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:590–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi Y, Osanai M, Lee GH. Fascin-1 expression correlates with repression of E-cadherin expression in hepatocellular carcinoma cells and augments their invasiveness in combination with matrix metalloproteinases. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1228–1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01910.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirghasemi A, Taheriazam A, Karbasy SH, Torkaman A, Shakeri M, Yahaghi E, Mokarizadeh A. Down-regulation of miR-133a and miR-539 are associated with unfavorable prognosis in patients suffering from osteosarcoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2015;15:86. doi: 10.1186/s12935-015-0237-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 20.Gu L, Sun W. MiR-539 inhibits thyroid cancer cell migration and invasion by directly targeting CARMA1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;464:1128–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, Li S, Yang X, Qiao B, Zhang Z, Xu Y. miR-539 inhibits prostate cancer progression by directly targeting SPAG5. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:60. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0337-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu C, Zhou R, Zhou Q, Chang Y, Jiang M. microRNA-539 suppresses tumor growth and tumorigenesis and overcomes arsenic trioxide resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Life Sci. 2016;166:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iguchi T, Aishima S, Umeda K, Sanefuji K, Fujita N, Sugimachi K, Gion T, Taketomi A, Maehara Y, Tsuneyoshi M. Fascin expression in progression and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:575–579. doi: 10.1002/jso.21377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Machesky LM, Li A. Fascin: Invasive filopodia promoting metastasis. Commun Integr Biol. 2010;3:263–270. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.3.11556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai WC, Jin JS, Chang WK, Chan DC, Yeh MK, Cherng SC, Lin LF, Sheu LF, Chao YC. Association of cortactin and fascin-1 expression in gastric adenocarcinoma: Correlation with clinicopathological parameters. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;55:955–962. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7235.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inamoto T, Taniguchi K, Takahara K, Iwatsuki A, Takai T, Komura K, Yoshikawa Y, Uchimoto T, Saito K, Tanda N, et al. Intravesical administration of exogenous microRNA-145 as a therapy for mouse orthotopic human bladder cancer xenograft. Oncotarget. 2015;6:21628–21635. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang ZC, Gao Q, Shi JY, Guo WJ, Yang LX, Liu XY, Liu LZ, Ma LJ, Duan M, Zhao YJ, et al. Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor S acts as a metastatic suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma by control of epithermal growth factor receptor-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Hepatology. 2015;62:1201–1214. doi: 10.1002/hep.27911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue M, Pang H, Li X, Li H, Pan J, Chen W. Long non-coding RNA urothelial cancer-associated 1 promotes bladder cancer cell migration and invasion by way of the hsa-miR-145-ZEB1/2-FSCN1 pathway. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:18–27. doi: 10.1111/cas.12844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen JJ, Cai WY, Liu XW, Luo QC, Chen G, Huang WF, Li N, Cai JC. Reverse correlation between microRNA-145 and FSCN1 affecting gastric cancer migration and invasion. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]