Abstract

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) are a good candidate for tissue engineering and clinical application. One of the challenges in its cell therapy is how to quickly obtain an adequate number of seed cells and meanwhile maintain suitable differentiation potential. In this study we combined three-dimensional (3D) collagen porous scaffolds with rotary cell culture system (RCCS) (RCCS-3D) to create a stereoscopic dynamic environment for the amplification of rat BMSCs in vitro. The results revealed that this RCCS-3D system could enhance BMSCs’ proliferation and colony formation, as well as maintain the differentiation potential compared with conventional static two-dimensional (2D) and 3D cell culture conditions. In addition, high-throughput microarray analysis showed that gene expressions of RCCS-3D system displayed significant differences in cell proliferation and differentiation compared with static-2D conditions. Thus, RCCS-3D system could provide an effective means for BMSCs cell proliferation in vitro and meanwhile maintain differentiation potential in tissue engineering.

Introduction

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) are ideal seed cells for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine due to their great properties of self-renewal and pluripotency. Moreover, autogenous BMSCs do not have exogenous gene safety issues and ethical problems involved in induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells1–3 and embryonic stem (ES) cells4. However, it’s still a challenge in clinical application of tissue-engineering to obtain sufficient quantities of BMSCs through static two-dimensional (2-D) expansion in vitro 5,6. What is worse, long-term sequential cell passaging results in loss of self-renewal and pluripotency in vitro 7.

The cells growing space environment and the dynamic environment can influence the seed cell fate8. Compared with conventional 2D cell culture, 3D cell culture has received wide attention for it could mimic a native cellular 3D niche in vivo to some extent, which is beneficial to the exchanges of nutrition and metabolism, extracellular matrix synthesis and forming of intricate cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions9. Extracellular matrix (ECM) plays a critical role in cell proliferation and differentiation in static condition in vitro 10–13. Collagen, the main component of ECM in vivo, is a major component of ECM and comprises the major (80–90%) organic component in mineralized bone tissues14. In physiological condition, collagenous stroma is conducive to apatite mineral deposition and the accumulation of noncollagenous and plasma proteins as well as proteoglycans14–16. Some studies suggested that 3D microenvironment could maintain the undifferentiated state of stem cells at static status17–19. Thus, collagen is a suitable cell carrier for favorable biocompatibility and protein-binding capacity.

Rotary cell culture system (RCCS) cannot only produce rotary movement to simulate microgravity effect by the method of vector-averaged gravity20,21 which makes cells losing their intracellular metabolic activity response to gravity and alters the cell perception of gravitational direction, but also provide a dynamic culture system for vital cell movements. Several studies have indicated that the effects of rotary culture on cell fate are multifaceted. Some studies show that rotary culture promoted the proliferation of human adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells without scaffolds22 and promoted various cell proliferations in rotating liquid vessel23–25. Others indicated that rotary culture maintains the undifferentiated state and enhances the neural repair potential of bone marrow stromal cells26 and promotes chondrogenesis of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells via the p38 MAPK pathway27.

In our study, after two or three passages, isolated BMSCs were seeded in cell culture dishes as static-2D group, on collagen scaffolds placed in dishes as static-3D group and on collagen scaffolds rotating in RCCS as RCCS-3D group, respectively. To investigate the effect of 2D static, 3D static and 3D rotary culture on BMSCs, cells cultured in dishes or scaffolds were directly applied to cell proliferation assay. Cells in each group were expanded for 7 days with proliferating L-DMEM medium and then transplanted into 2D cell culture dishes for evaluating colony-forming ability, osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation potential and the expressions of genes associated with osteogenesis and adipogenesis by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). Furthermore, a microarray analysis was introduced to identify potential molecular markers and GO biological process across different culture conditions. We found that RCCS-3D system enhances BMSCs proliferation and maintains the differentiation potential.

Results

Characterization of BMSCs

The primary BMSCs displayed a fibroblast-like morphology and developed to visible colonies after 3–5 days culture (Fig. 1a). After 2 weeks, the cells showed their typical big spindle shape morphology and lined almost next to each other (Fig. 1b). To obtain sufficient cell numbers, we performed the follow studies after 2 weeks in culture. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the cells were uniformly positive for CD29 and CD90, but negative for the hematopoietic surface markers CD11b/c and CD45 (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

(a) Phase-contrast image of BMSCs colonies in the primary culture. Scale bar = 200 μm. (b) Phase-contrast image of BMSCs after three passages. Scale bar = 200 μm. (c) Fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis revealed that cells were positive for CD29 and CD90 expression and negative for CD11b/c and CD45.

Properties of collagen scaffolds and establishment of cell culture models

The collagen material was cut into 4 mm in diameter and 1 mm thick collagen scaffolds (Fig. 2a). SEM analysis showed the collagen scaffolds exhibited interconnecting porous structures whose diameter of pore size reached 40 μm to 100 μm (Fig. 2b). The porous structure of the collagen scaffolds was beneficial to the exchange of nutrition and the metabolism in cultured cells. In RCCS-3D group, cells on collagen scaffolds revolved around the vessel axis at uniform speed in rotating liquid (Fig. 2c). In static-2D and static-3D group, cells were transplanted on dishes and on collagen scaffolds in medium (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

The morphology of BMSCs on 2D culture plate and 3D scaffolds. (a) Macrophotograph of 3D collagen porous scaffolds. (b) SEM image of 3D porous scaffolds. Scale bar = 400 μm. (c) Macrophotograph of BMSCs cultured in RCCS-3D group. (d) Macrophotograph of BMSCs cultured in static-2D group and static-3D group.

Morphology and growth of cells

For the analysis of the growing status of the cells in different groups, alive cells were stained by FDA and visualized by laser scanning confocal microscope. At third day, cells in each condition grew well (Fig. 3a,c and e). Cell density in each condition increased with the extension of the cultivation time (Fig. 3b,d and f). However, the cells in RCCS-3D group exhibited a plump morphology expanding along the scaffold structure. Furthermore, it can be seen that cells expanding in RCCS-3D group established tight cell-cell junctions (Fig. 3f). Through SEM analysis, the cells in 2D condition cultured for 3 days showed typical elongated spindle-like morphology adhered to flat plastic surface (Fig. 4a). On the contrary, the static-3D and the RCCS-3D group cells emerged various morphological changes penetrated into the pores of 3D collagen scaffolds (Fig. 4c and e). With the cells expanding to the 7th day, intercellular gaps in the RCCS-3D group almost completely contacted (Fig. 4f), while cells on 2D flat plastic surface proliferated slowly and cells on static collagen scaffolds did not completely form cell-cell tight junctions (Fig. 4b and d).

Figure 3.

Confocal images of BMSCs stained with FDA in static-2D group after 3 days (a), 7 days (d), static-3D group after 3 days (b), 7 days (e), and RCCS-3D group after 3 days (c), 7 days (f). Scale bar = 200 μm.

Figure 4.

SEM images of BMSCs grown in static-2D group after 3 days (a), 7 days (d), static-3D group after 3 days (b), 7 days (e), and RCCS-3D group after 3 days (c), 7 days (f). Scale bar = 20 μm.

Cell proliferation and colony-forming assay

To investigate the cell growth of BMSCs in 3 groups, we examined cell proliferation at day 0, 1, 3, 5, and 7 by counting the total number of cells. The cells number in each group increased along with the time points (Fig. 5a). The difference between RCCS-3D group and static-2D group or static-3D group on the 7th day was significant (P < 0.05). Loading efficacy was designed to evaluate the loading efficacy of cells in each group. We found the loading efficacy of cells on static-2D group, static-3D group and RCCS-3D group were 88.3% ± 4.2%, 72.8% ± 5.2% and 67.0% ± 8.4% (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Cell number and CFU analysis of BMSCs cultured in static-2D, static-3D and RCCS-3D groups. (a) Proliferation curves of BMSCs in static-2D, static-3D and RCCS-3D groups. The fold increase of cell number was calculated at 0, 1, 3, 5 and 7 day, normalized with the fold increase of cells was set as 0 on the seeding day. The difference on the 7th day was significant by one-way ANOVA analysis (*p < 0.05). (b) Loading efficacy of cells in static-2D, static-3D and RCCS-3D groups. (c) Statistical analysis of colony numbers of BMSCs in each group (n = 3, *p < 0.05). (d–f) Morphology of colonies formed by the cells in static-2D group (d), static-3D group (e) and RCCS-3D group (f) and the colonies were stained with crystal violet.

After transferring to 2D 10 mm cell culture dishes and cultured for 12 days, the cells in all the 3 groups formed colonies (Fig. 5d,e and f). However, more colonies were formed in RCCS-3D group than that in static-2D and static-3D conditions (Fig. 5c).

Microarray data

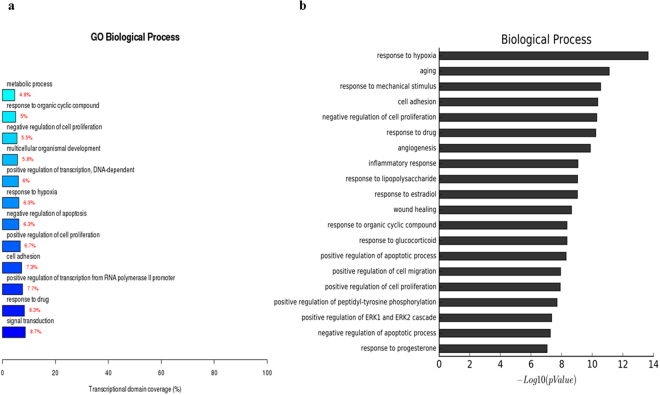

The gene expression analysis of the three groups showed that 1775 genes were upregulated and 1830 were downregulated in RCCS-3D group compared to that in the static-2D group, 1889 genes were upregulated and 1700 downregulated in static-3D group compared to that in the static-2D group, and 244 genes were upregulated and 465 were downregulated in RCCS-3D group compared to that in the static-3D group. Compared with the transcriptional domain coverage of the differential genes in biological process of static-2D group, RCCS-3D group showed the differences of differential genes mainly concentrated in signal transduction, cell adhesion, cell proliferation, apoptosis, gene transcription, response to hypoxia, multicellular organismal development and metabolic (Fig. 6a). Compared to static-2D group, there were top 20 terms based on most significant p value of biological process in RCCS-3D group were involving in response to hypoxia, cell adhesion, regulation of apoptosis, and regulation of cell proliferation, etc. (Fig. 6b). And we can also see the results of the terms based on most significant p value in cellular component differential genes analysis and the transcriptional domain coverage of the differential genes analysis were mainly involving in focal adhesion, intracellular organelles and extracellular matrix, etc. (Fig. 7a,b). In addition, results of the terms based on biological process and cellular component analysis in RCCS-3D group vs static-3D group were less significantly differential compared with RCCS-3D group vs static-2D group (Figs 8a,b and 9a,b). The top 20 up-regulation gene expression of positive regulation of cell proliferation analysis and negative regulation of apoptotic process in biological process analysis were displayed in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 6.

The RCCS-3D vs static-2D group comparison that gene ontology analysis of differentially expressed genes in biological process. (a) Top 20 terms based on most significant p value of biological processes. (b) Top 12 terms based on the differential genes were most extensive transcriptional domain coverage.

Figure 7.

The RCCS-3D vs static-2D group comparison that gene ontology analysis of differentially expressed genes in cellular component. (a) Top 20 terms based on most significant p value of biological processes. (b) Top 12 terms based on the differential genes were most extensive transcriptional domain coverage.

Figure 8.

The RCCS-3D vs static-3D group comparison that gene ontology analysis of differentially expressed genes in biological process. (a) Top 20 terms based on most significant p value of biological processes. (b) Top 12 terms based on the differential genes were most extensive transcriptional domain coverage.

Figure 9.

The RCCS-3D vs static-3D group comparison that gene ontology analysis of differentially expressed genes in cellular component. (a) Top 20 terms based on most significant p value of biological processes. (b) Top 12 terms based on the differential genes were most extensive transcriptional domain coverage.

Table 1.

Top 20 up-regulation gene expression of positive regulation of cell proliferation in biological process analysis.

| UniGene ID | Gene Title | Gene Symbol | Regulation | Fold Change (3DR vs 2DS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rn.53973 | colony stimulating factor 3 (granulocyte) | Csf3 | up | 171.62158 |

| Rn.33146 | cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide | Camp | up | 48.08884 |

| Rn.102416 | secreted frizzled-related protein 2 | Sfrp2 | up | 40.572308 |

| Rn.198483 | interleukin 11 | Il11 | up | 37.9506 |

| Rn.10232 | adrenomedullin | Adm | up | 30.882835 |

| Rn.6282 | insulin-like growth factor 1 | Igf1 | up | 21.025723 |

| Rn.42897 | epiregulin | Ereg | up | 18.446724 |

| Rn.98842 | fibroblast growth factor 7 | Fgf7 | up | 15.823176 |

| Rn.44285 | colony stimulating factor 2 | Csf2 | up | 11.562983 |

| Rn.9873 | interleukin 6 | Il6 | up | 10.630553 |

| Rn.10468 | hepatocyte growth factor | Hgf | up | 9.064637 |

| Rn.48749 | wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 5A | Wnt5a | up | 7.5712037 |

| Rn.130193 | cardiotrophin-like cytokine factor 1 | Clcf1 | up | 7.039917 |

| Rn.44216 | KIT ligand | Kitlg | up | 6.747355 |

| Rn.1716 | interleukin 6 receptor | Il6r | up | 5.9479833 |

| Rn.162144 | T-box 3 | Tbx3 | up | 5.3641796 |

| Rn.9664 | activating transcription factor 3 | Atf3 | up | 5.3632503 |

| Rn.10568 | amphiregulin | Areg | up | 4.8201013 |

| Rn.1923 | vascular endothelial growth factor A | Vegfa | up | 4.6613054 |

| Rn.12138 | interleukin 6 signal transducer | Il6st | up | 4.5940213 |

Table 2.

Top 20 up-regulation gene expression of negative regulation of apoptotic process in biological process analysis.

| UniGene ID | Gene Title | Gene Symbol | Regulation | Fold Change (3DR vs 2DS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rn.119611 | angiopoietin-like 4 | Angptl4 | up | 679.1727 |

| Rn.16279 | twist homolog 2 (Drosophila) | Twist2 | up | 159.442 |

| Rn.11412 | endothelin receptor type B | Ednrb | up | 111.2116 |

| Rn.161953 | angiopoietin 1 | Angpt1 | up | 84.16098 |

| Rn.198135 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 3 | Bcl3 | up | 55.382526 |

| Rn.102416 | secreted frizzled-related protein 2 | Sfrp2 | up | 40.572308 |

| Rn.10488 | superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial | Sod2 | up | 21.491787 |

| Rn.19770 | BCL2-related protein A1d | Bcl2a1d | up | 16.618256 |

| Rn.107266 | chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1 | Cx3cl1 | up | 14.690553 |

| Rn.6800 | platelet factor 4 | Pf4 | up | 14.353208 |

| Rn.31427 | microphthalmia-associated transcription factor | Mitf | up | 11.888482 |

| Rn.44285 | colony stimulating factor 2 (granulocyte-macrophage) | Csf2 | up | 11.562983 |

| Rn.9873 | interleukin 6 | Il6 | up | 10.630553 |

| Rn.1780 | clusterin | Clu | up | 10.37447 |

| Rn.10468 | hepatocyte growth factor | Hgf | up | 9.064637 |

| Rn.48749 | wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 5A | Wnt5a | up | 7.5712037 |

| Rn.27923 | BTG family, member 2 | Btg2 | up | 7.554541 |

| Rn.6051 | dipeptidase 1 (renal) | Dpep1 | up | 7.429901 |

| Rn.44216 | KIT ligand | Kitlg | up | 6.747355 |

| Rn.62694 | nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 3 | Nr4a3 | up | 5.482495 |

Adipogenic differentiation ability analysis

To detect the adipogenic differentiation of the cells in different culture conditions after 7 days expanding, each group cells were transplanted to 2D plates and induced to adipogenic differentiation for 21 days. Before transplanted to 2D plates and induced to adipogenic differentiation, the RNA transcripton level of the markers of adipocytes such as adipocyte fatty acid binding protein(AP2) and Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) of the static-3D and RCCS-3D groups were increased compared to that of the static-2D group (Fig. 10a). And the RNA transcripton level of the markers of adipocytes such as CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α(C/EBPα), adipocyte fatty acid binding protein(AP2) and Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) of the static-3D and RCCS-3D groups were increased significantly compared to that of the static-2D group (Fig. 10b). Meanwhile, the adipogenic differentiation images of the three groups suggested that more red lipid droplets stained by oil red O were formed in static-3D (Fig. 11b and e) and RCCS-3D groups (Fig. 11c and f) than that in the static-2D group (Fig. 11a and d).

Figure 10.

Adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in static-2D, static-3D and RCCS-3D groups. (a) Q-PCR analysis of adipogenic gene expression levels and osteogenic gene expression levels before BMSCs in each group transplanted to 2D plates for 21 days adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation (N = 3, *p < 0.05). (b) Q-PCR analysis of adipogenic gene expression levels and osteogenic gene expression levels after BMSCs transplanted to 2D plates for 21 days adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in each group (N = 3, *p < 0.05).

Figure 11.

Oil red O staining (a–f) and Von kossa staining (g–i) of BMSCs transplanted to 2D plates for 21 days adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation.

Osteogenic differentiation ability analysis

To detect the osteogenic differentiation of the cells in different expanding conditions after 7 days, each group cells were transplanted to 2D plates and induced to on for 21 days. Before transplanted to 2D plates and induced to osteogenic differentiation, the RNA transcription level of the markers of osteocytes such as bone morphogenetic protein 2(BMP2), Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and Collagen type I (ColI) of the static-3D and RCCS-3D groups were increased compared to that of the static-2D group (Fig. 10a). And the expression levels of osteogenesis-related genes, odontogenesis-related transcription factors Osterix (OSX), bone sialoprotein (BSP), osteopontin (OPN), bone morphogenetic protein 2(BMP2), Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), osteocalcin(Ocn), runt related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) and Collagen type I (ColI) were significantly elevated (P < 0.05) in RCCS-3D group compared to that in the static-2D group and static-3D group at day 21 when normalized to GAPDH (Fig. 10b). And the Von Kossa staining was carried out to visualize the calcium deposition in cells. Cells derived from RCCS-3D group (Fig. 11g) tended to form more calcium deposition stained by silver compared to that in the static-2D group (Fig. 11h) and static-3D group (Fig. 11i).

Discussion

In this study, we combined three-dimensional collagen porous scaffolds with rotary cell culture system to pursue an available approach to expand sufficient seed cells and maintain their pluripotency for tissue engineering applications. 3D porous natural collagen scaffolds were used to provide an appropriate 3D niche for accreting ECM due to their biocompatibility and protein-binding capacity, which was conducive to MSCs to maintain the differentiation potential. In the 3D microenvironment, the cell populations could interface with their surrounding environment and expand with similar to that occurred during in vivo. In addition, the results of cell number count and CFU assay showed RCCS could promote the cell proliferation and self-renew of BMSCs on the 3D collagen scaffold. To some extent, 3D rotary cell culture may be a feasible method to massively amplify seed cells for bioengineering in vitro.

Self-renewal is the intrinsic property of stem cells that allows them to extensively proliferate, prevent apoptosis, and avoid loss of multiple differentiation potential. It is well-known that mesenchymal stromal cells cannot avoid aging and loss of their proliferative capacity and differentiation potential progressively in traditional static-2D culture system. The 3D structure and dynamic environment of RCCS-scaffold system provides suitable conditions for deposition of extracellular matrix. Extracellular matrix has a positive role on the cell proliferation, anti-apoptosis resistance, anti-aging and cell differentiation28–30. RCCS-3D system has promoted the cell proliferation compared with static-2D system based on the cell fold increasing curves and colony-forming assay. Moreover, the porous 3D scaffold structure and liquid surface tension of cell suspension may cause a certain amount of cell loss on the cell culture dishes during cell inoculation. Therefore, the actual number of 3D scaffolds cells ought to be less than the count number, that is, it may be systematic error that the actual fold increase values of 3D groups may be higher than the ones of experimental data. And perhaps this is why the loading efficient of 3D groups were lower than static-2D group. Additionally, the cell bodies of RCCS-3D group displayed more plump and full morphology. And RCCS-3D system might promote the production of intracellular and extracellular based on the cellular component analysis of microarray data, which may indicate that the system enhanced cell biological activity. According to the results of microarray analysis, the differential genes of RCCS-3D group showed significant differences in biological process including response to hypoxia, aging, regulation of apoptosis, proliferation and cell migration compared with static-2D group. Moreover, compared with the transcriptional domain coverage of the differential genes in static-2D group, RCCS-3D group showed the differences of differential genes mainly concentrated in signal transduction, cell adhesion, cell proliferation, apoptosis, gene transcription, response to hypoxia, multicellular organismal development and metabolic. Therefore, it is easy to see that RCCS-3D cell culture system showed significant differences in cytoplasm and their organelles as well as the extracellular matrix compared with traditional static-2D cell culture.

According to the result of the regulation of proliferation and apoptosis in microarray analysis, we can learn some enlightenments that RCCS-3D system enhanced the expression of genes related to proliferation and apoptosis. Angiopoietin-like 4 is a potential anti-apoptotic factor for MSCs. Previous studies have reported that Angptl4 protects MSCs from hypoxia/SD-induced apoptosis by increasing the Bcl-2/Bax ratio and the MMP31. Other studies also reported that Angpt1 enhanced the survival and functional recovery of transplant MSC via PI3K/Akt pathway activation32. Twist can block the myogenic differentiation, leading to halting the terminal differentiation and inhibition of the apoptosis33. SFRP2, an important autocrine factor for MSCs themselves, has recently been highlighted for its therapeutic potential in tissue engineering. Recent studies have shown that sFRP2-expressing MSCs exhibit an increased proliferation rate and inhibit both MSC apoptosis and their differentiation along osteogenic and chondrogenic lineages by blocking the effect of canonical Wnt3a and inhibiting both Wnt and bone morphogenic protein (BMP) signaling pathways34,35. Epiregulin (Ereg), one member of the EGF family, can activate MEK/Erk and JNK signalling pathways. Moreover, a previous study has demonstrated that blocking JNK signalling could abolish the effect of Ereg on the proliferation of human dental stem cells, suggesting that JNK signalling was also involved in EREG-mediated cell proliferation36. Recently, Platelet factor 4 (PF4) has been suggested to enhance the ability of adherent and proliferation of BMSC while inhibiting its apoptosis37. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) is thought to be a growth factor found in the fast-growing stem cell clones to induce BMSCs proliferation38. Additionally, a study shows that IL-6 is a critical factor for maintaining the stemness of adult human bone marrow-derived MSCs39. It regulates both MSC proliferation and inhibition of differentiation through ERK1/2 activation as the key pathway.

Microenvironment and mechanical stimulation of ECM have great impact on cellular activities40. The space structure of scaffold provides complex surfaces for cell attachment and growth. In Fig. 4, we can see that multiple contacts of cells and 3D interface in scaffold displayed cell morphology diversity that are analogous to axon and soma of neurons differing from typical spindle cell morphology in static-2D system. According to biological process and cellular component of microarray analysis, RCCS-3D system vs static-2D system showed significant differences in cell adhesion, extracellular matrix microenvironment and response to mechanical stimulation. Focal adhesions provide cells mechanical transmission pathways to respond to their microenvironment41. ECM elasticity is able to regulate FAK activity to trigger relative signal molecules to regulate cell differentiation and different elastic substrate can lead to different results42. The potential impact of prior expansion of the rat BMSCs in plastic dishes on the differentiation potential of the post-expansion on 3D scaffolds could not be avoided in our study for the rare number and the separation of original MSCs. The impact might have always existed during the prior expansion, which could also influence subsequent differentiation. The rotating mechanical environment and the multipath contact conduction of 3D space structure in scaffold provide complex force field environment for cells to sense the constantly changing direction of gravity, which is similar to different matrix elastic strength mechanical stimulation. The cells in RCCS-3D system may exhibit multicellular organismal differentiation potential.

In this study, after the 7 days expanding in proliferation culture medium, the cells in each group were transplanted to 2D plates and induced to adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation. And we assayed mRNA expressions of the essential adipogenesis-related and osteogenesis-related markers. The results exhibited that more red lipid droplets stained by oil red O in static-3D and RCCS-3D groups in comparison with that in static-2D group and more calcium deposition stained by silver compared to static-2D group and static-3D group. The expressions of both adipogenic and osteogenic genes were upregulated significantly in varying degrees during adipogenic and ostogenic differentiation. C/EBPa is an essential transcription factor for the induction of terminal adipocyte differentiation43. Fatty acid binding protein 4/AP2 (Fabp4), a member of the cytoplasmic fatty acid-binding protein family, was detected to express in adipose tissue and its expression was highly regulated during the differentiation of adipocytes44. LPL is synthesized in tissues involved in fatty acid metabolism45. A study demonstrated that ex vivo expansion of MSCs on the collagen matrix results in the retention of the adipogenic differentiation potential in vitro. Moreover, the transcript levels of Fabp4 and LPL were demonstrated to be significantly higher in the cells ex vivo expanded on the collagen matrix in comparison with the cells ex vivo expanded on cultured on TCP46. Recent study has identified that JNK-dependent noncanonical WNT-5a signaling is important to maintain the potential of multipotent stem cells to undergo osteogenesis47. It is possible that the culture method in our study involving the dynamic and 3D tissue-engineering model stimulates the up-regulation of wnt5a (Table 2), suggesting that this culture system is beneficial for maintaining the multiple differentiation potential of the adult stem cells for a long term growth in vitro 48. Osterix and Runx2 are two essential transcription factors for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation49. OPN is highly expressed during the last stage of bone formation, namely the mineralization period50. ALP is an earlier osteogenic marker that increases rapidly with the proliferation and external secretion of osteoblasts, while BSP has activated the function in the initiation of mineralization, both of which are relatively mature osteogenic differentiation markers51. The increased oil red staining and Von Kossa staining in RCCS-3D group as well as the assays of mRNA expressions of adipogenesis-related and osteogenesis-related markers suggested that RCCS-3D system could maintain the potential of adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation when MSCs loading on the collagen 3D scaffolds after a long-term culture, while 2D BMSCs tended to lose their differentiation potential after expanding for same long- term time.

In summary, we developed an effective RCCS-3D means for BMSCs cell proliferation in vitro and meanwhile maintain differentiation potential in tissue engineering in vitro. The mechanisms of 3D dynamic BMSCs culture are complicated and multiple signal pathways including growth, differentiation, and apoptosis are involved. Further studies on the internal connection among the up-regulated genes should shed light on the mechanism by which the combination of three-dimensional culture and RCCS promotes the proliferation and maintains the differentiation potential of BMSCs.

Methods

Collagen scaffold preparation

The collagen material was provided by Zhenghai Biotechnology Inc. (Shandong, China). The preparation method of collagen was described previously52. Briefly, collagen material was cut into 4 mm in diameter and 1 mm high cylinder. Then, the collagen scaffolds were crosslinked according to the procedure adopted from Zhao et al. 53. Briefly, the scaffolds were soaked into 2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid solution (pH 5.6) with Nhydroxysulfosuccinimide (NHS, 1.2 mg/mL) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl aminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC, 3 mg/mL, respectively). After crosslinking at 37 °C for 4 hours, the scaffolds were washed with 0.1 M Na2HPO4 for 4 hours and with 4 M NaCl overnight to remove the remaining crosslinking reagents, followed by washing with ddH2O for half an hour at least eight times, and then freeze-dried overnight. At last, the collagen scaffolds selected based on the previous size standard at 4 mm (diameter) × 1 mm (height) were sterilized by gamma irradiation before further experiments.

Preparation of rBMSCs and cell-scaffold complexes

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) were isolated from the marrow cavities of tibias and femora of Sprague Dawley rat (8 weeks). The animal experimentation was performed in accordance with NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the United National Institutes of Health. All experimental protocols were approved by the Review Committee for the Use of Human or Animal Subjects of Dalian Medical University). Briefly, the marrow was flushed out from the tibias and femora with Low Glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (L-DMEM) containing 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. Cells were centrifuged and suspended in proliferating L-DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 mmol/L non-essential amino acids, 100 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. Then they were placed on a culture dish and cultured in an incubator under humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37 °C. Nonadherent cells were removed on day 3 and the proliferating medium was changed every 2 days. Cells were passaged at 80% confluence. After two or three passages, cells were used in following tests. Collagen scaffolds were placed in a 100 mm culture dish, 10 ul of 2 × 104 cells suspension was dropwise added on the surface of the collagen scaffold, and the cell-scaffold complex was incubated in 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for 4 hours. After 4 hours, the cell-scaffold complexes of RCCS-3D group were removed in a sterile container rotating culture system, and 50 ml cell culture medium was added slowly until filling with a 10 ml syringe vent emptying bubble in the rotating culture system container. After the container is mounted to the rotary cultivator machine bed, adjusting a rotational speed of 20 rev/min. The system is placed in the rotary cultivator 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. The cell-scaffold complexes of static-3D group were removed in cell culture dishes added with 50 ml cell culture medium. The cells of static-2D group were seeded directly in cell culture dishes.

Flow cytometry (FCM) analysis

The third passage MSCs were harvested by digested with 0.25% trypsin, and suspended in PBS containing 2% FBS. Cells were incubated on ice for 30 min with anti-rat antibodies (BioLegend) conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE). Markers of BMSC (CD29-PE and CD90-PE) and Hematopoietic cell (CD11b/c-FITC and CD45-PE) were evaluated and analyzed respectively. FITC- or PE-conjugated IgG were used as isotype control. After washing three times, cells were analyzed on Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorter (FACS).

Fluorescein diacetate(FDA) for living cell staining

The samples of the three groups were washed with PBS and incubated in 10 μg/ml fluorescein diacetate(FDA) for 30 seconds at room temperature. Then the scaffolds were washed at least three times with PBS and observed with laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

The surface morphological characteristics of scaffolds and the cell morphology of static-2D group, static-3D group and RCCS-3D group cells were observed with SEM respectively. After the cells in each group were cultured for 3 days and 6 days, they were gently removed from medium and fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C overnight. Subsequently, the samples were dehydrated by a gradient concentration ethanol series of 30%, 50%, 75%, 80%, 85%, 90%, 95% and 100% and then immersed in isoamyl acetate overnight. After CO2 critical point drying, the samples were coated with gold and analyzed by a scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi Science Systems).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation assay was performed with cell counting. BMSCs were seeded with an initial density of 20,000 cells per scaffold or 8000 cells per 35 mm culture dish. Every sample was cultured in proliferating L-DMEM medium and the medium was changed every 3 days. After the cells in each group were cultured for 0, 1, 3, 5 and 7 days, they were digested with 0.25% trypsin to count the cell number respectively. Cell multiplications were expressed as a relative value that the fold increase of cells was set compared with the seeding cell density. The time of seeding after 4 hours was set as 0 day.

Colony-forming unit-fibroblasts (CFU-F) assay

Cells cultured for 7 days in each group were harvested by treatment with 0.25% trypsin. 1000 cells were plated in 10 cm culture dishes and three replicate plates were used for each group. Then the cells were cultured for 12 days and the medium was changed every 3 days. Upon harvesting, the cells were washed with PBS and stained with 0.25% crystal violet solution for 10 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the colonies (containing > 50 cells) were counted with microscopic observation.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the cultured cells with Trizol (Invitrogen) reagent, and the contaminated genomic DNA was removed with Deoxyribonuclease I (Invitrogen). The first-strand complementary cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScriptTM III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). qPCR was performed using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in combination with a CFX96 system (Bio-Rad). The relative mRNA level was expressed as fold change relative to untreated controls after normalization to the expression of GAPDH by the 2−ΔΔCT method. The thermocycler parameters were 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. The target genes and primer sequences are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Primer sequences used for qPCR amplification.

| Gene Title | Gene Symbol | primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH | F:5¡−-AGAGACAGCCGCATCTTCTTG-3¡− |

| R:5¡−-ACCGACCTTCACCATCTTGTCTA-3¡− | ||

| Alkaline phosphatase | ALP | F:5¡−-CCGATCGGGACTGGTACTC-3¡− |

| R:5¡−-TCAGTTCTGTTCTTGGGGTACA-3¡− | ||

| Osteocalcin | OCN | F:5¡−-GAGGGCAGTAAGGTGGTGAA-3¡− |

| R:5¡−-GTCCGCTAGCTCGTCACAAT-3¡− | ||

| Osteopontin | OPN | F:5¡−-TGTCCTCTGAAGAAACGGATG-3¡− |

| R:5¡−-ACAGAATCCTCGCTCTCTGC-3¡− | ||

| Bone sialoprotein | BSP | F:5¡−-CGGCCACGCTACTTTCTTTA-3¡− |

| R:5¡−-CCCTCCTCCTCCGAACTATC-3¡− | ||

| Collagen type I | COLI | F:5¡−-CATGTTCAGCTTTGTGGACCT-3¡− |

| R:5¡−-GGTTTCCACGTCTCACCATT-3¡− | ||

| Runt-related transcription factor 2 | RunX2 | F:5¡−-CTTCACAAATCCTCCCCAAG-3¡− |

| R:5¡−-GAGGCGGTCAGAGAACAAAC-3¡− | ||

| Osterix | OSX | F:5¡−-CACTGGCTCCTGGTTCTCTC-3¡− |

| R:5¡−-GCTGTTGAGTCTCGCAGAGG-3¡− | ||

| Bone morphogenetic protein 2 | BMP2 | F:5¡−-AGACCACCGGCTGGAGAG-3¡− |

| R:5¡−-TGAGAAACTCATCAGTAGGGACAG-3¡− | ||

| CCAAT/enhancer binding protein, alpha | C/EBPa | F:5¡−-AAGTCGGTGGATAAGAACAGC-3¡− |

| R:5¡−-TCAACTCCAACACCTTCTGC-3¡− | ||

| Adipocyte lipid-binding protein | AP2 | F:5¡−-GATTTCCTTCAAACTGGGCG-3¡− |

| R:5¡−-TGACACATTCCACCACCAGC-3¡− | ||

| Lipoprotein lipase | LPL | F:5¡−-CAGCTGGGCCTAACTTTGAG-3¡− |

| R:5¡−-AATGGCTTCTCCAATGTTGC-3¡− |

Microarray analysis

To compare the gene expression of cells in each group, microarray analysis was performed by Shanghai OE Biotech Co., Ltd. Simply, the total RNA was extracted according to the method mentioned above and its clean-up was performed using QIAGEN RNeasy Kit. The double strand cDNA was synthesized using 500 ng of total RNA. The in vitro transcription was performed to synthesize RNA amplification (aRNA). Samples were labeled using the GeneChip 3′IVT Express Kit (Affymetrix). The labeled aRNA was fragmented (35–200 nt) and hybridized to a GeneChip Rat Genome Array (Affymetrix). The size of aRNA fragmentation was checked by electrophoresis using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). The hybridization was performed for 16 h at 60 rpm and 45 °C in the GeneChip Hybridization Oven 640 (Affymetrix). The Gene Chip Fluidics Station 450 (Affymetrix) was used to wash and stain the probe array according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The scanning of the samples was performed using the GeneChip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix).

Affymetrix GeneChip Command Console (version 4.0, Affymetrix) was used to analyze array images to get raw data. Next, Genesrping software (version 12.5; Agilent Technologies) was employed to finish the basic analysis with the raw data. To begin with, the raw data was normalized with the MAS5 algorithm. The probes that at least 100.0 percent of samples in any 1 out of 2 conditions have flags in “P” were chosen for further data analysis. Differentially expressed genes were then identified through fold change. The threshold set for up- and down-regulated genes was a fold change ≥2.0.

The osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation assay

To investigate the difference of cell pluripotency after 7 days expanding under the different culture conditions the cells were digested with 0.25% trypsin and transplanted into 6-well plate and cultured with osteogenic or adipogenic induction medium for 21 days respectively.

The osteogenic induction medium was consisted of L-DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 nmol/L dexamethasone, 10 mmol/L sodiumβ-glycerophosphate, and 0.05 mmol/L L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (Sigma) and replaced every 3 days. Von kossa staining and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) for osteoblastic markers were used for analysing the differences of the osteogenic ability among the 3 groups.

For adipogenic differentiation analysis, cells in each group were incubated in H-DMEM medium supplemented with 1 mmol/L dexamethasone (Sigma), 0.2 mmol/L indomethacin(Sigma), 10 mg/mL insulin(Roche), 0.5 mmol/L 3-isobutyl-1- methyl-xanthine (IBMX) (Sigma), and 10% FBS for 21 days. The adipogenic induction medium was replaced every 3 days. Oil red O staining and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) for adipogenic gene expression were used for analysing the differences of the adipogenic ability among the 3 groups.

Oil red O staining

Each group sample was fixed in 4% formalin for 5 min. 0.5% Oil red O solution (sigma) was prepared in isopropanol and diluted 3:2 (v:v) with deionized water. Each sample was incubated with 1 mL Oil red O for 15 min at room temperature. After rinsed 3 times with PBS, samples were visualized under D5100 Digital Camera (Nikon).

Von Kossa staining

The cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and then rinsed with deionized water. After a brief air dry, the samples were exposed to ultraviolet light in 1% aqueous silver nitrate under UV exposure for 30 min. Calcium deposition was appeared as black spots, and then the samples were rinsed fully with distilled water and 5% sodium thiosulfate to fix the positive dark staining and remove excess silver nitrate. Then the samples were visualized under D5100 Digital Camera (Nikon).

Statistical analysis

All data were performed at least three times and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA test and p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Nos 2011CB710905), the “Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences” (Grant No. XDA04020202-19) and the “National Natural Science Foundation of China” (81271719).

Author Contributions

Yilong Tang carried out the experiments. Zhifeng Xiao, Yannan Zhao and Jing Li provided reagents tools. Yilong Tang, Sufang Han, Lei Chen and Bin Dai conceived the study, designed the experiments and analyzed the data. Yilong Tang and Yan Xu wrote the manuscript. Hong Wang, Ling Wang and Bing Chen revised the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Yilong Tang and Yan Xu contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ling Wang, Email: whwl2003@tom.com.

Bing Chen, Email: jwdai@genetics.ac.cn.

Hong Wang, Email: whwl@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Zhang Y, et al. Intramyocardial transplantation of undifferentiated rat induced pluripotent stem cells causes tumorigenesis in the heart. PloS one. 2011;6:e19012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutierrez-Aranda I, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cells develop teratoma more efficiently and faster than human embryonic stem cells regardless the site of injection. Stem cells. 2010;28:1568–70. doi: 10.1002/stem.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-David U, Benvenisty N. The tumorigenicity of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:268–77. doi: 10.1038/nrc3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wert dW, Mummery C. Human embryonic stem cells, research, ethics and policy. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:672–682. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pittenger MF, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dominici M, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madeira A, da Silva CL, dos Santos F, Camafeita E, Cabral JM, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cell expression program upon extended ex-vivo cultivation, as revealed by 2-DE-based quantitative proteomics. PloS one. 2012;7:e43523. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Xu H, Wan C, McCaigue M, Li G. Bioreactor expansion of human adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2052–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Provin C, Takano K, Sakai Y, Fujii T, Shirakashi R. A method for the design of 3D scaffolds for high-density cell attachment and determination of optimum perfusion culture conditions. J Biomech. 2008;41:1436–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu H, et al. Cultured cell-derived extracellular matrix scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2011;32:9658–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindner U, et al. Improved proliferation and differentiation capacity of human mesenchymal stromal cells cultured with basement-membrane extracellular matrix proteins. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:992–1005. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.510503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen XD, Dusevich V, Feng JQ, Manolagas SC, Jilka RL. Extracellular matrix made by bone marrow cells facilitates expansion of marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells and prevents their differentiation into osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1943–56. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badylak SF, Freytes DO, Gilbert TW. Extracellular matrix as a biological scaffold material, Structure and function. Acta biomater. 2009;5:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaro Sodek, Marc DM. Molecular and cellular biology of alveolar bone. Periodontology. 2000;24:99–126. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2240106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landis WJ, Hodgens KJ, Arena J, Song MJ, McEwen BF. Structural relations between collagen and mineral in bone as determined by high voltage electron microscopic tomography. Microsc Res Tech. 1996;33:192–202. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19960201)33:2<192::AID-JEMT9>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arena J, et al. A study of the mineralization of bone by high voltage electron microscopic tomography. Proc Electr Microsc Soc Am. 1992;50:582–583. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei XH, et al. NASA-approved rotary bioreactor enhances proliferation of human epidermal stem cells and supports formation of 3D epidermis-like structure. PloS one. 2011;6:e26603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han S, et al. The three-dimensional collagen scaffold improves the stemness of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. J Genet Genomics. 2012;39:633–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu B, et al. Simulated microgravity using a rotary cell culture system promotes chondrogenesis of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells via the p38 MAPK pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;414:412–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sievers A, Hejnowicz Z. How well does the clinostat mimic the effect of microgravity on plant cells and organs? ASGSB bulletin. 1992;5:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klaus DM. Clinostats and bioreactors. ASGSB bulletin. 2001;14:55–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen X, Xu H, Wan C, McCaigue M, Li G. Bioreactor expansion of human adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem cells. 2006;24:2052–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuge L, et al. Microgravity potentiates stem cell proliferation while sustaining the capability of differentiation. Stem Cells Dev. 2006;15:921–9. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.15.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samuelson L, Gerber DA. Improved function and growth of pancreatic cells in a three-dimensional bioreactor environment. Tissue eng, Methods. 2013;19:39–47. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li S, et al. NASA-approved rotary bioreactor enhances proliferation and osteogenesis of human periodontal ligament stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:1273–82. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuge L, et al. Simulated microgravity maintains the undifferentiated state and enhances the neural repair potential of bone marrow stromal cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:893–900. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu B, et al. Simulated microgravity using a rotary cell culture system promotes chondrogenesis of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells via the p38 MAPK pathway. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2011;414:412–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heo JS. et al. Poly-L-lysine prevents senescence and augments growth in culturing mesenchymal stem cells ex vivo. Biomed Res Int.2016, Article ID 8196078 (online), 13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Shekaran A, et al. Biodegradable ECM-coated PCL microcarriers support scalable human early MSC expansion and in vivo bone formation. Cytotherapy. 2016;10:1332–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Y, et al. Effects of human fibroblast-derived extracellular matrix on mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2016;5:560–572. doi: 10.1007/s12015-016-9671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hou M, et al. Angiopoietin-like 4 confers resistance to hypoxia/serum deprivation-induced apoptosis through PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 signaling pathways in mesenchymal stem cells. PloS one. 2014;9:e85808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Liu XB, et al. Angiopoietin-1 preconditioning enhances survival and functional recovery of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Journal of Zhejiang University Science B. 2012;13:616–23. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1201004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maestro R, et al. Twist is a potential oncogene that inhibits apoptosis. Gene Dev. 1999;13:2207–17. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alfaro MP, et al. sFRP2 suppression of bone morphogenic protein (BMP) and Wnt signaling mediates mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) self-renewal promoting engraftment and myocardial repair. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35645–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.135335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alfaro MP, et al. The Wnt modulator sFRP2 enhances mesenchymal stem cell engraftment, granulation tissue formation and myocardial repair. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18366–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803437105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao Y, et al. Epiregulin can promote proliferation of stem cells from the dental apical papilla via MEK/Erk and JNK signalling pathways. Cell Proliferat. 2013;46:447–56. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen JJ, Gao Y, Tian Q, Liang YM, Yang LD. Platelet factor 4 protects bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from acute radiation injury. Brit J of Radiol. 2014;87:1084. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mareddy S, Dhaliwal N, Crawford R, Xiao Y. Stem cell-related gene expression in clonal populations of mesenchymal stromal cells from bone marrow. Tissue eng. 2010;16:749–58. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pricola KL, Kuhn NZ, Haleem-Smith H, Song Y, Tuan RS. Interleukin-6 maintains bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell stemness by an ERK1/2-dependent mechanism. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108:577–88. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steward AJ, Kelly DJ. Mechanical regulation of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. J. Anat. 2015;227:717–731. doi: 10.1111/joa.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andrew MH, et al. Tissue stiffness dictates development, homeostasis, and disease progression. Organogenesis. 2015;11:1–15. doi: 10.1080/15476278.2015.1019687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adam JE, et al. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrison RF, Farmer SR. Hormonal signaling and transcriptional control of adipocyte differentiation. J Nutr. 2000;130:3116s–21s. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.12.3116S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glatz JF, Borchers T, Spener F, van der Vusse GJ. Fatty acids in cell signalling, modulation by lipid binding proteins. Prostag Leukotr Ess. 1995;52:121–7. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(95)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janderova L, McNeil M, Murrell AN, Mynatt RL, Smith SR. Human mesenchymal stem cells as an in vitro model for human adipogenesis. Obes res. 2003;11:65–74. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mauney JR, Volloch V, Kaplan DL. Matrix-mediated retention of adipogenic differentiation potential by human adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells during ex vivo expansion. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bilkovski R, et al. Role of WNT-5a in the determination of human mesenchymal stem cells into preadipocytes. J biol chem. 2010;28:6170–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.054338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuo CK, Tuan RS. Mechanoactive tenogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue eng. 2008;14:1615–27. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2006.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baglio SR, Devescovi V, Granchi D, Baldini N. MicroRNA expression profiling of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells during osteogenic differentiation reveals Osterix regulation by miR-31. Gene. 2013;527:321–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kollmer M, Buhrman JS, Zhang Y, Gemeinhart RA. Markers Are Shared Between Adipogenic and Osteogenic Differentiated Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J Dev Bio tissue eng. 2013;5:18–25. doi: 10.5897/JDBTE2013.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang S, et al. Transcriptional regulation of bone sialoprotein gene by interleukin-11. Gene. 2011;476:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen B, et al. Homogeneous osteogenesis and bone regeneration by demineralized bone matrix loading with collagen-targeting bone morphogenetic protein-2. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1027–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao Y, et al. Crosslinked three-dimensional demineralized bone matrix for the adipose-derived stromal cell proliferation and differentiation. Tissue eng. 2009;15:13–21. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]