Abstract

Basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins, which are characterized by a conserved bHLH domain, comprise one of the largest families of transcription factors in both plants and animals, and have been shown to have a wide range of biological functions. However, there have been very few studies of bHLH proteins from perennial tree species. We describe here the identification and characterization of 175 bHLH transcription factors from apple (Malus × domestica). Phylogenetic analysis of apple bHLH (MdbHLH) genes and their Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis) orthologs indicated that they can be classified into 23 subgroups. Moreover, integrated synteny analysis suggested that the large-scale expansion of the bHLH transcription factor family occurred before the divergence of apple and Arabidopsis. An analysis of the exon/intron structure and protein domains was conducted to suggest their functional roles. Finally, we observed that MdbHLH subgroup III and IV genes displayed diverse expression profiles in various organs, as well as in response to abiotic stresses and various hormone treatments. Taken together, these data provide new information regarding the composition and diversity of the apple bHLH transcription factor family that will provide a platform for future targeted functional characterization.

Introduction

Numerous plant-specific transcription factors (TFs) have been shown to play important roles regulating the development of plant-specific organs and adaptations to terrestrial environments1. The bHLH proteins constitute one of the largest TF families and share a conserved domain of approximately 60 amino acids, including a 15-amino acid basic region and a HLH region that contains two amphipathic α-helices with a linking loop that varies in length2. The basic region is involved in binding to specific DNA sequences, while dimerization with other HLH-containing proteins occurs through the HLH region, and is a prerequisite for DNA binding2.

Since the bHLH domain was initially defined2, a variety of bHLH subgroups have been identified based on the frequencies of 19 conserved amino acids in the bHLH consensus motif2. Structural analyses of animal bHLH proteins indicated that they comprise only six groups (designated A-F)3, while phylogenetic analyses have shown that plant bHLH proteins comprise 26 subgroups, twenty of which are present in the common ancestors of extant mosses and vascular plants, and six additional subgroups that evolved among the vascular plants4.

In animals, bHLH proteins are involved in regulating responses to environmental signals, controlling cell cycle and circadian rhythms, and modulating a range of developmental processes, such as neurogenesis, myogenesis, sex and cell lineage determination, proliferation, and differentiation3,5. In addition, functions in processes such as chromosome segregation, general transcriptional enhancement, and metabolism regulation have been demonstrated in unicellular eukaryotes, such as budding yeast6. In plants, the founding member of the bHLH superfamily is the maize (Zea mays) R gene, which plays a key role in anthocyanin biosynthesis7. Subsequently, many more functions for plant bHLH genes have been identified, including the regulation of light signaling8,9; hormone signal transduction10; responses to wounding, drought, salt and oxidative stresses11 and low temperatures12; iron deficiency13; symbiotic ammonium transport14 and flavonoid synthesis15. In addition, plant bHLH TFs also influence the development of shoot branches16, fruits and flowers17,18, microspores19, trichomes20,21, stomata22 and roots23.

Despite studies of the plant bHLH TFs from different plant species, only a few have previously been characterized in perennial tree species24. In this study, we explored the evolution and structure of the bHLH TF family in apple (Malus × domestica Borkh) through phylogenetic analysis and integrated synteny analysis with orthologs from the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis), combined with exon/intron structural analysis. These analyses provide evidence that the bHLH domain is highly conserved and that the bHLH TFs from these two species share a common ancestor. In addition, we evaluated the expression profiles of MdbHLH genes in ten different plant structures, and measured their transcript abundance in response to different phytohormone treatments and following exposure to high-salt stress. These results revealed that the bHLH TFs exhibit a wide range of expression patterns, indicating functional diversity. This study represents an important step in elucidating the biological and molecular functions of apple bHLH TFs, as well their evolutionary diversification.

Results

Genome-wide identification of apple bHLH TF protein encoding genes

To identify apple bHLH protein encoding genes, we searched the predicted apple proteome using an HMM algorithm (HMMER) with the bHLH conserved domain (PF00010) and the definition of bHLH proteins reported by Atchley et al. 2. After re-checking the structural integrity of the conserved domains using SMART software (http://smart.emblheidelbergde/) and removing any redundant proteins, a total of 175 bHLH proteins were defined. Based on a multiple sequence alignment (Supplementary Fig. S1), the proteins were named sequentially as MdbHLH001 to MdbHLH175, based on the equivalent classification in Arabidopsis and rice (Oryza sativa)4. At least one expressed sequence tag (EST) was identified for each of 82 MdbHLH genes from the NCBI apple ETS database (Supplementary Table S1). Interestingly, MdbHLH142 had two HLH domains, with Expect (E)-values of 3.65E-17 and 2.77E-08 and sequence identity of 33%, a phenomenon reported in other species, including Caenorhabditis elegans and rice25,26. However, the biological function of this type of bHLH protein remains to be determined.

Detailed information regarding each member of the apple bHLH family, including gene locus numbers, accession numbers for the full-length sequences deposited at NCBI, chromosomal location, the length of protein sequences, open reading frames, and phylogeny relationship to Arabidopsis bHLH proteins, is listed in Supplementary Table S2. The annotation process revealed a substantial range in the lengths of the predicted proteins, from 92 to 1,397 amino acids, suggesting that the apple bHLH family may have a long evolutionary history and contribute to numerous biological processes.

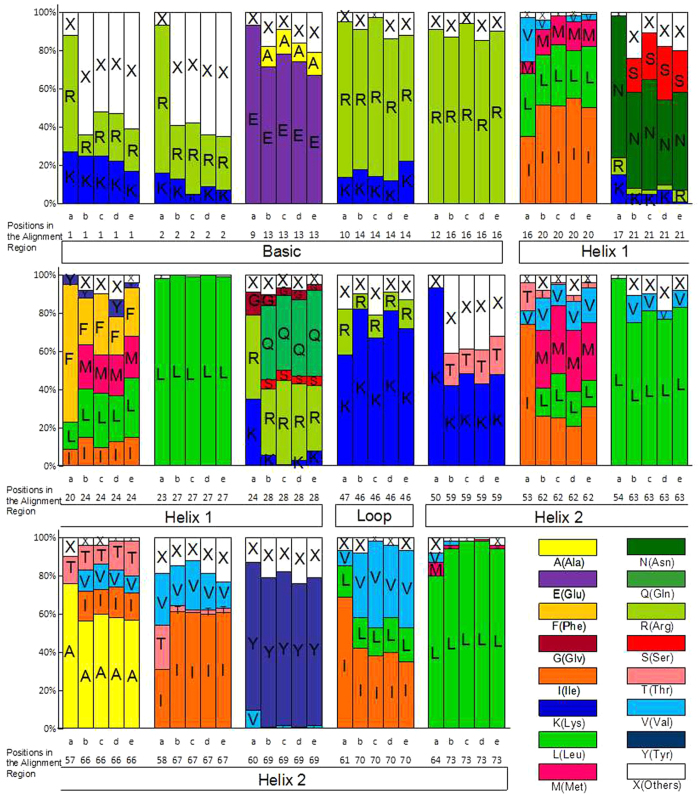

Sequence conservation within the MdbHLH motifs was evaluated in the context of known bHLH proteins from animals, Arabidopsis, rice (Oryza sativa) and poplar (Populus trichocarpa)2,27,28. bHLH proteins are known to share 19 residues that are homologous between family members: five in the basic region, five in the first helix region, one in the loop region and eight in the second helix region. Typically, a protein is categorized as a bHLH protein if it contains 11 or more of these residues2,27, or nine or ten for group C and D bHLH proteins, because these groups do not have typical basic regions29, but are capable of binding to other bHLH proteins30. The conservation of 11 conserved residues (Glu-13, Arg-14, Arg-16, Asn-21, Leu-27, Lys-46, Leu-63, Ala-66, Ile-67, Tyr-69, and Leu-73 in our alignment) of the 19 conserved residues is shown in Fig. 1, demonstrating that the bHLH motifs are much more closely related among plant bHLH proteins than between bHLH proteins from plants and animals. The Leu-27 residue is highly conserved among bHLH proteins from all the examined organisms, suggesting that it may play an important role in the dimerization, which commonly occurs between bHLH proteins27,28.

Figure 1.

Amino acid distribution in the bHLH consensus motif. In columns labeled (a), percentage refers to the 392 animal bHLH proteins identified by Atchely et al. 2. In columns labeled (b,d and e), percentage refers to the 158 AtbHLH genes, the 183 PtbHLH genes and the 173 OsbHLH genes, respectively, as reported by Carretero-Paulet et al. 28. In columns labeled (c), percentage refers to the 175 MdbHLH genes identified in this current study. The numbers below (a,b,c,d and e) refer to the positions of the residues in the alignments of the studies.

Phylogenetic analysis of apple and Arabidopsis bHLH genes

To understand the evolutionary relationship of the bHLH TFs between species, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the 175 apple bHLH sequences and 158 sequences from Arabidopsis (Fig. 2). The apple bHLH genes were distributed among 23 of the 26 total clades (subgroups), whereas some bHLH proteins did not align within any particular subgroup, and were thus termed ‘orphans’4.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on apple and Arabidopsis bHLH transcription factors. The phylogenetic tree was generated with CLUSTALW and using the neighbor-joining method. The phylogenetic tree was inferred using MEGA 5.0 software. Reliability of the predicted tree was tested using bootstrapping with 1000 replicates. Numbers at the nodes indicate how often the group to the right appeared among bootstrap replicates. Branch lines of subtrees are colored indicating different bHLH subgroups. Apple and Arabidopsis bHLH genes in the same subgroup are denoted by squares (□), circles (○), triangles (Δ) and diamonds (◇) in various colors respectively.

To provide further insight into the phylogenetic relationships, we assessed the number of genes representing each bHLH subgroup member for Arabidopsis, apple, poplar and rice (Supplementary Table S3). In apple, there were no members in groups X, XIII and XIV, indicating that gene deletions may have occurred during evolution. The numbers of apple bHLH genes within subgroups Ib(2), II, III(a + c), IVc, IVd, VII(a + b), VIIIa, IX, and XII were similar to that seen for Arabidopsis (apple to Arabidopsis ratio of between 0.7 and 1.25)31. Six subgroups (Ia, IVc, Va, Vb, VIIIb and XII) showed similar gene numbers between apple and poplar, while 11 subgroups (Ia, III(a + c), Iva, IVc, Vb, VII(a + b), VIIIb, VIIIc(1), VIIIc(2), XI and XII) showed similar gene number between apple and rice. The most striking difference in gene numbers within bHLH subfamilies was seen within the IIId+e subgroup, with apple exhibiting ~3-fold or greater increase in representation compared with the other three plant species. In contrast, the numbers of bHLH genes within subgroup IIIf in apple was only half or less of that seen for the other species. This suggests that these subgroups have been subject to expansion or contraction, respectively, following the divergence of apple.

Sequence and structure analysis of apple bHLH TFs

A phylogenetic tree with the 175 apple bHLH conserved domain sequences was constructed using the neighbor-joining method (Fig. 3a). The topology was consistent with that constructed from the Arabidopsis homologs (Fig. 2), and nearly all of the members in the same subgroup appeared to be clustered together. An exception was, MdbHLH012 and MdbHLH013, which fell into subgroup III (a + c) in the previous analysis comparing apple and Arabidopsis (Fig. 2), but in the present study clustered with the members of subgroup IIIb. When the conserved bHLH motifs were analyzed using MEME software (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table S4), the members of each subgroup had similar motifs, although the lengths of the corresponding proteins were markedly different (Fig. 3b). The number of introns varied considerably among bHLH genes, ranging from zero to 19 (Fig. 3c); however, in some subgroups, the structural pattern of all members was similar. For example, none of the members of subgroup VIIIb (MdbHLH118-MdbHLH124) had an intron, while the number of introns in genes from subgroup Ia (MdbHLH068-MdbHLH080) ranged from two to four, and the corresponding proteins had a conserved motif position.

Figure 3.

The structure of apple (Malus×domestica) bHLH transcription factors. (a) The phylogenetic trees were constructed using aligned domains of the MdbHLH transcription factors with MEGA 5.0 software. Reliability of the predicted tree was tested using bootstrapping with 1000 replicates. Numbers at the nodes indicate how often the group to the right appeared among bootstrap replicates. Subtrees branch lines are colored indicating different bHLH subgroups. (b) MEME analysis of MdbHLH protein motifs. The motifs, numbered 1–10, are depicted as different colored boxes. The sequence information for each motif is provided in Supplementary Table S4. Motifs 1 and 2 correspond to the bHLH domain. (c) Exon/intron structures of MdbHLH transcription factors. Exons are represented by black boxes, whereas black lines connecting two exons represent an intron. Both exons and introns were drawn to scale.

Expansion patterns of the apple bHLH TF family

Segmental and tandem duplications are known to be key factors driving gene family expansion32. In our study, the chromosomal localization of the 175 MdbHLH genes (Fig. 4) revealed that they were unevenly distributed among chromosomes, while 26 pairs of MdbHLH genes were identified that likely arose from segmental duplication (Supplementary Table S5). The analysis of tandem duplication events was based on the methods of Holub33, where a chromosomal region within 200 kb containing two or more genes was defined as a tandem duplication event. Accordingly, 47 genes were identified as being involved in tandem duplication events and these were associated with 23 clusters distributed among apple chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14 and 16 (Supplementary Table S6).

Figure 4.

Distribution and synteny analysis of MdbHLH genes on the apple (Malus×domestica) chromosomes. The locations of the apple bHLH genes are indicated by vertical black lines. Colored bars connecting two chromosomal regions denote syntenic regions in apple. Chr, chromosomes.

Synteny analysis

To clarify the origin of the apple bHLH TFs and the evolutionary relationship between the apple and Arabidopsis families, a large-scale comparative synteny map was created. Forty-one pairs of bHLH genes, including 30 AtbHLH genes and 31 MdbHLH genes, showed syntenic relationships (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table S7), indicating that large-scale expansion occurred prior to the divergence of Arabidopsis and apple. Among the synteny events, many pairs were single apple to Arabidopsis correspondences, such as MdbHLH009-AtbHLH021 and MdbHLH120-AtbHLH088; however, some exceptions were identified. For example, some syntenic correspondences included more than one apple gene, such as MdbHLH077/MdbHLH078-AtbHLH098 and MdbHLH090/MdbHLH091-AtbHLH062, whereas others included more than one Arabidopsis gene, such as MdbHLH020-AtbHLH006/AtbHLH004/AtbHLH028 and MdbHLH022-AtbHLH013/AtbHLH017. These results suggest that the many of MdbHLH genes share a common ancestor with AtbHLH genes counterparts. Despite the relatively close evolutionary relationship between the apple and Arabidopsis, the chromosomes of apple have undergone extensive rearrangement and fusions.

Figure 5.

Synteny analysis of bHLH genes between apple and Arabidopsis. Apple and Arabidopsis bHLH genes are indicated by vertical black lines. Colored bars denote syntenic regions between apple and Arabidopsis bHLH genes. Chr, chromosomes.

Expression patterns of MdbHLH genes in various organs and at different developmental stages

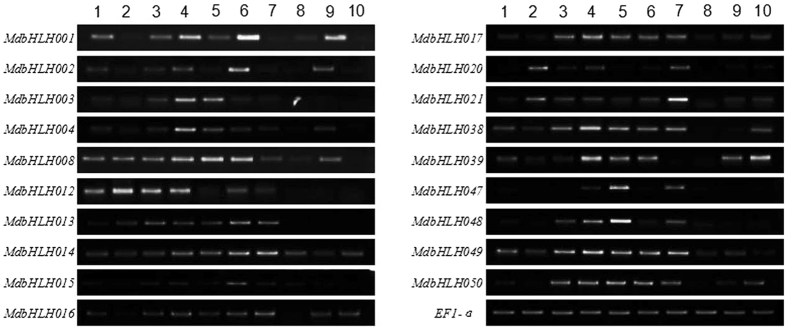

Subgroup III and IV bHLH proteins may participate in plant defense and development28,34. Accordingly, to further verify the functions of these identified MdbHLH genes, 19 MdbHLH genes (MdbHLH001-004, MdbHLH008, MdbHLH012-017, MdbHLH020-021 and MdbHLH038-039 from subgroup III, and MdbHLH047-050 from subgroup IV) were selected randomly to examine the expression in ten different structures and developmental stages: apical buds, roots, stems, young leaves, mature leaves, flower buds, young fruit, seeds of young fruit, mature fruit and seeds of mature fruit (Fig. 6). All 19 genes were expressed in at least one of the ten structures, although some clear spatial differences in expression were noted. For example, MdbHLH012 was preferentially expressed in roots, MdbHLH038 and MdbHLH039 were highly expressed in young leaves, and MdbHLH021 was predominantly expressed in young fruit. MdbHLH015 and MdbHLH002 were preferentially expressed in flower buds, and MdbHLH047 and MdbHLH048 were preferentially expressed in mature leaves.

Figure 6.

Expression profiles of 19 MdbHLH genes in 10 apple structures/organs. CDNA derived from the indicated structures/organs was used for the amplification of MdbHLH sequences using gene specific primers. Lanes: 1-apical buds, 2-roots, 3-stems, 4-young leaves, 5-mature leaves, 6-flower buds, 7-young fruit, 8-mature fruit, 9-seeds of young fruit, 10-seeds of mature fruit. All PCR reactions, including those amplifying the EF1-α control sequence, were carried out under similar conditions with variable number of amplification cycles. The experiments were repeated three times and the results were consistent. Representative results are shown.

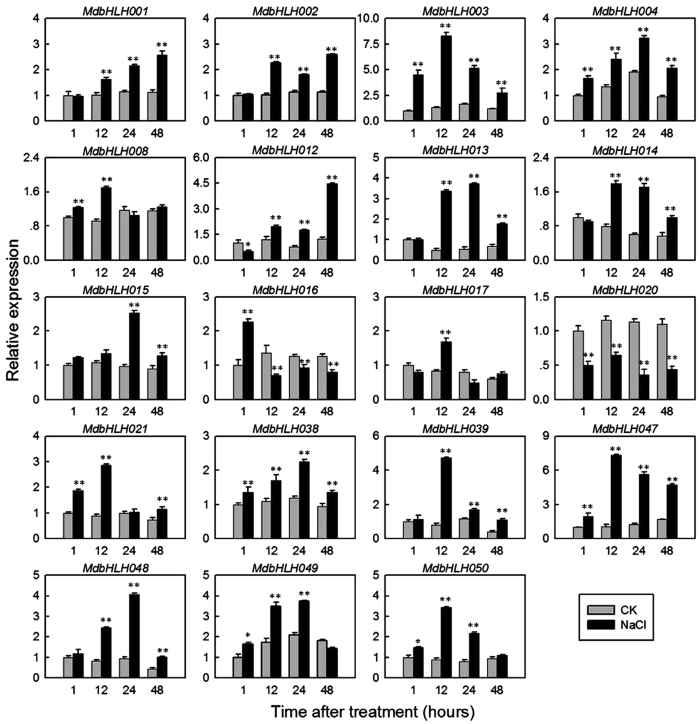

Expression of MdbHLH genes in response to high salt stress conditions

To investigate the possible roles of the 19 selected MdbHLH genes in abiotic stress responses, we evaluated their expression in the leaves of apple seedlings that had been subjected to high salt stress. Almost all the genes were up-regulated, to varying degrees, except that MdbHLH020 showed clear down-regulation (Fig. 7). However, the timing of the changes in expression varied considerably: MdbHLH016 showed a peak of expression at a relatively early time point (1 h after the onset of the high salt treatment), whereas MdbHLH001 and MdbHLH012 were up-regulated at a relatively late time point (48 h after the onset of high salt treatment) (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

qRT-PCR analysis of 19 MdbHLH genes in response to salt stress. The expression levels were normalized to 1 h CK (check; deionized water) sample. Samples were harvested at 1 h, 12 h, 24 h and 48 h after 250 mM NaCl treatment or CK. Mean values and SDs were obtained from three biological and three technical replicates. Asterisks indicate the corresponding gene was significantly up- or downregulated under salt treatment (t-test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

MdbHLH expression in response to hormone treatments

Phytohormones are critically important in coordinating regulatory networks and the signal transduction pathways associated with external cues. Abscisic acid (ABA), methyl-jasmonate (MeJA), Gibberellins (GAs), salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (Eth) have all been reported to play important roles in responses to both biotic and abiotic stresses35. In the present study, we examined the effects of hormone treatments on the expression profiles of selected members of Group III (MdbHLH001-004, 008, 012–017, 020–021 and 038–039) and Group IV (MdbHLH047-050) MdbHLHs using real-time quantitative PCR (Fig. 8). Among the 19 targeted genes, 14 were up-regulated (defined as Log2-fold increase of at least 2.0 in all three biological replicates) by the ABA treatment, and the transcript levels of two genes (MdbHLH003 and MdbHLH004) were highest at the first sampling time and decreased thereafter. Moreover, the transcript level of one gene (MdbHLH013) was high at the third sampling time but low at the other sampling times, suggesting the transcript is less stable for this gene. The other genes showed no changes in transcript levels. After MeJA treatment, 13 genes were up-regulated, including MdbHLH012, MdbHLH013, MdbHLH047 and MdbHLH048, while MdbHLH003 was down-regulated at later time points. The expression profiles after the SA, GA and Eth treatments were distinct from those modulated by ABA and MeJA, with substantial numbers of down-regulated genes being observed. After SA treatment, one gene (MdbHLH050) was down-regulated, and 15 were up-regulated; after GA treatment, two genes (MdbHLH012 and MdbHLH020) were down-regulated, and 14 were up-regulated; after Eth treatment, four genes (MdbHLH003, MdbHLH004, MdbHLH015 and MdbHLH017) were down-regulated, and 12 were up-regulated. These different transcriptional responses indicate that the MdbHLH gene family is collectively regulated by a broad set of hormonal signals.

Figure 8.

Expression profiles of 19 MdbHLH genes in response to various hormones. The results of the quantitative RT-PCR were analyzed using Gene Tools software, and the relative expression levels of MdbHLH genes under the various treatments compared to the controls were used for hierarchical cluster analysis using MeV 4.8.1. The color scale represents relative expression levels, with red indicating increased transcript abundance and green indicating decreased transcript abundance. The following five hormone treatments were tested: abscisic acid (ABA), methyl jasmonic acid (MeJA), salicylic acid (SA), gibberellin (GAs), and ethylene (Eth).

Discussion

Basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins comprise a large superfamily of eukaryotic TFs that play central roles in a wide range of metabolic, physiological and developmental processes36. Numerous bHLH TFs have been identified and well characterized in many plant species; however, relatively little is known about these proteins in tree species such as apple. In the present study, we identified the members of the apple bHLH TFs family and described their structure and evolutionary history. Apple is one of the most economically important fruit crops in the world, and there is considerable interest in improving its resistance to various stresses. Since bHLH TFs are known to regulate stress responses we also analyzed the expression patterns of MdbHLH genes in response to salt stress.

Of the 23 MdbHLH subgroups, three (Ib (2), IIId + e and XV) include only angiosperm protein encoding genes, while the remaining 20 include proteins from both angiosperms and lycophytes3. Since the last common ancestor of angiosperms and lycophytes dates to before 415 million years ago (Mya)37, this implies that these 20 bHLH subgroups are at least 415 million years (My) old. Interestingly, 18 of these subgroups include sequences from not only vascular plants but also bryophytes3. The oldest physical evidence for the existence of vascular land plants is trilete spores in Upper Ordovician sediments38, which suggests that these subgroups are more than 443 My old, and IVc subgroup contain a protein from green algae that suggests this subgroup may be over 1 billion years old3,39. This long evolutionary history is consistent with the apparent functional diversity of the genes observed in this study.

Gene duplication events play a major role in genomic rearrangements and expansions40 and are defined as either tandem duplications, with two or more genes located on the same chromosome without insertion, or segmental duplications, with duplicated genes present on different chromosomes41. In our study, 66 of the 175 (38%) apple bHLH genes that could be precisely located on chromosomes were associated with either tandem or segmental duplication events (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). This is a lower percentage than that of duplication events in rice26 but still suggests that tandem and segmental duplications played a key role in the expansion of the apple bHLH family.

We conducted a MEME analysis to detect the conservation of motifs in MdbHLH gene family, and we found 10 highly conversed motifs based on all the 175 protein sets. Motifs 1 and 2 which are bHLH domains present in almost all the bHLH proteins, motifs 6 and 10 are unique in subgroup III(d + e), and the other motifs were conserved in each of the same subgroups. Taken together, all the non-bHLH conserved motifs in each subgroup support the phylogenetic relationship shown in Fig. 3a, suggesting that these extra domains are necessary for the function of each MdbHLH subgroup. The pattern of introns can provide important evidence to support phylogenetic relationships within a gene family26. Exon/intron diversification of gene family members has played an important role in the evolution of multiple gene families through three main types of mechanism: exon/intron gain/loss, exonization/pseudoexonization, and insertion/deletion42. A previous study of 167 rice bHLH genes found that the number of introns ranged from zero to four, and that all the genes could be assigned to ten different patterns based on the presence and positions of introns25. In our study, the intron number of the 175 MdbHLH genes varied from zero to 19, with more than 10 introns being present in only seven genes and zero to seven introns in 89% of the genes. We conclude that exon/intron gain/loss or divergence occurred during the evolutionary history of the apple bHLH family. Moreover, the gain/loss and divergence may reflect chromosomal rearrangement and fusion32 that has resulted in the functional diversity of the apple bHLH proteins.

Plant bHLH proteins have been associated with diverse metabolic, biosynthetic and regulatory pathways, especially those related to abiotic stress responses43. Prior to this current study, only a few MdbHLH genes have been functionally characterized: the few examples include MdbHLH3, which promotes anthocyanin accumulation and fruit coloration in response to low temperature44, MdCIbHLH1 (Cold-Induced bHLH1), which encodes an ICE-like protein and is induced in response to cold stress45, and MdbHLH104, the overexpression of which in apple enhances tolerance of iron deficiency46. However, since approximately 40% of the Arabidopsis bHLH genes/proteins have been functionally characterized, phylogenetic/sequence analyses and sequence comparisons of apple bHLH proteins with their Arabidopsis orthologs provides an opportunity to predict the functions of the MdbHLH genes.

We found that selected genes belonging to subgroups III and IV exhibited diverse transcription profiles in all 10 organs/tissues examined, indicating distinct functions in apple development. The preferential expression of MdbHLH021 in young fruit for example, might suggest a role for this gene in fruit development. MdbHLH001 and MdbHLH002 showed similar expression patterns in apical buds, stems, leaves, flower buds and young seeds, and are orthologous to AtbHLH116 (also called ICE1), suggesting redundant function in cold response.

Studies of bHLH subgroups have shown that subgroup IIId proteins negatively regulate JA-mediated plant defense and development47 and Arabidopsis TFs from bHLH subgroups IIIe and IIId negatively regulate JA-induced leaf senescence34. Furthermore, it was reported that a single amino acid substitution in AtMYC1 from Arabidopsis bHLH subgroup IIIf leads to trichome and root hair patterning defects by abolishing interaction with partner proteins48. These results suggest that the bHLH subgroup III TFs have a variety of biological functions.

ABA is often described as a stress hormone because of its notable roles in responses to stressful environments, as well as being associated with physiological processes such as storage, dehydration at later stages of embryogenesis, seed maturation, dormancy formation and abscission49. The observed ABA responsiveness of all the selected 19 MdbHLH genes, especially MdbHLH002, MdbHLH004, MdbHLH008, MdbHLH014, MdbHLH015 and MdbHLH048 (Fig. 8), suggests that these members of apple subgroups III and IV may be involved in stress responses. MeJA, a jasmonic acid derivative, mediates numerous transcriptional responses to wounding, herbivory and pathogenesis50, and the MdbHLH002, MdbHLH012, MdbHLH013, MdbHLH017, MdbHLH020, MdbHLH021, MdbHLH047 and MdbHLH048 genes were clearly up-regulated by a MeJA treatment, whereas MdbHLH003 was down-regulated at a later time point. This indicates that the corresponding MdbHLH proteins are components of the MeJA-induced transcriptional network. GA stimulates plant cell elongation, promotes flowering, and releases seed/tuber dormancy35, and a previous study demonstrated that bHLH TFs participate in shoot branching and flower development16–18. Here we found that some MdbHLH genes were up-regulated by GA treatment, while others were down-regulated, providing evidence for the involvement of a subset of MdbHLH in GA-induced pathways. After Eth treatment, a clear down-regulation in the expression of MdbHLH003, MdbHLH004, MdbHLH015, and MdbHLH017 was observed (Fig. 8). Given that Eth is an important signaling molecule in many processes, including root and root hair growth, cell fate determination, and responses to biotic and abiotic stress49, the results presented here indicate that the regulatory role of bHLH proteins under different stresses is complicated. Future studies will seek to clarify the underlying regulatory mechanisms and cross-talk between these signaling pathways.

Materials and Methods

Identification and annotation of the apple bHLH TF family

The bHLH conserved domain (Pfam PF00010; http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/)51 was used to analyze a draft apple genome sequence52, as well as the GenBank non-redundant protein database and the apple genome sequence database on the website GDR (Genome Database for Rosaceae, https://www.rosaceae.org/), using HMMER (Hidden Markov Model, HMM) software53. Only proteins with e-values < 0.01 were considered for further analysis54. Then we checked the predicted bHLH transcription factors in the iTAK database (http://bioinfo.bti.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/itak/index.cgi) to retrieve any additional bHLH genes. We also used the coding sequences (CDS) to perform blast searches against the Phytozome database (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html#). Any additional bHLH genes were retrieved for further analysis. To further verify the reliability of those bHLH candidate sequences, domain structures analysis software SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de) was used to analyze the sequence integrity of the bHLH domain. Redundant sequences or sequences lacking of the bHLH domain were removed. Expressed sequences tags (ESTs) of apple EST database from NCBI were used for further validation. The Arabidopsis bHLH gene sequences were obtained from the Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR; https://www.arabidopsis.org/) using BLASTP with default parameters53.

Multiple sequence alignment, phylogenetic analysis, and classification of apple bHLH genes

A total of 175 predicted MdbHLH proteins, with amino acids spanning the bHLH core domain, were subjected to a multiple sequence alignment using ClustalX 2.0 with the default parameters55. A further multiple sequence alignment including MdbHLH genes and those from Arabidopsis (AtbHLH) was performed using CLUSTALW53. The phylogenetic tree representing Arabidopsis and apple bHLH proteins was generated using MEGA 5.0 software and the neighbor-joining method56, with the following settings: mode, “p-distance”; gap setting, “Complete Deletion”; and bootstrap test replicate, “1,000”.

Analyses of exon-intron structure and distribution of conserved motifs in MdbHLH genes

Exon–intron organization was determined based on alignments of coding sequences and genomic sequences (https://www.rosaceae.org/) and diagrams were created using the online Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS: http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.ch). The lengths and sequence information of the conserved motifs of apple bHLH proteins, other than the bHLH domains, were obtained using MEME 4.11.2 (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) software with default settings, except that motif count was set to 10 and motif width to between 8 and 50.

Tandem duplication and synteny analysis

Examples of tandem duplication were identified based on physical chromosomal location: homologous bHLH genes on a single chromosome, with no other intervening genes, were characterized as genes involved in tandem duplication events57. The specific physical location of each MdbHLH gene on its chromosome therefore determined whether it was regarded as a gene resulting from a tandem duplication event. The syntenic blocks used for constructing a synteny analysis map of the apple bHLH genes, as well as a comparison of apple and Arabidopsis bHLH genes, were obtained from the Plant Genome Duplication Database58, and the synteny diagrams were generated using Circos version 0.63 (http://circos.ca/).

Plant material and treatments

Malus × domestica cv. Fuji growing on M.26 rootstocks planted at the College of Horticulture, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China (34°20′N 108°24′E) was used in this research. Apple organs were obtained as follows: roots (newly growing lateral roots of 1–2 mm in diameter); stems (near the apices of newly growing shoots, 3–4 mm in diameter); apical buds; flower buds; young leaves; the third to fifth fully expanded young leaf beneath the shoot apex when shoots were 40~60 cm in length; mature leaves, defined as those on the middle to lower part of growing shoots; flowers; young green fruit (~60 days after full bloom); mature fruit (~100 days after full bloom); and seeds from young and mature fruit were collected from 9–10 year old field grown plants59.

For salt stress and hormone treatments, two-year old ‘Fuji’ seedlings growing in pots (30 cm × 26 cm × 22 cm) filled with a 5:1:1 mixture of forest soil: sand: organic substrate were used. Seedlings were irrigated with 2 L of 250 mM NaCl59, and leaves were collected at 1, 12, 24, and 48 h post-treatment. Plants irrigated with the same volume of water were used as a negative control. To confirm effectiveness of the salt treatment, we confirmed that the expression of SALT OVERLY SENSITIVE MdSOS1 and MdSOS2, which are components of the SOS pathway60, was up-regulated (Supplementary Figure S2). Hormone treatments were performed by spraying leaves with 300 μM ABA, 50 μM MeJA, 100 μM SA, 100 µM GA, or 0.5 g/L Eth (released from ethephon), followed by sampling at 1, 12, 24, and 48 h after treatment. Leaves sprayed with deionized water and collected at the same time points were used as negative controls. Each treatment contained three replicates of 15 plants each. All plant samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction59,61.

Expression analysis of MdbHLH genes

Total RNA was extracted from the apple samples using an EZNA Plant RNA Kit (R6827-01, Omega Bio-tek, USA), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription of 500 ng total RNA using PrimeScript RTase (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China). The apple gene EF1-α (GenBank accession number DQ341381) with the primers F (5′-ATT CAA GTATGC CTG GGT GC-3′) and R (5′-CAG TCA GCC TGT GATGTT CC-3′) was used as an internal control. Gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S8) were designed for the selected bHLH genes using Primer Premier 5.0. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR assays were carried out using the following profile: 94 °C for 2 min, 28–38 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 56–61 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension of 72 °C for 2 min. For each gene, the number of amplification cycles was adjusted such that an amplification product was easily apparent in at least one sample. In each case, 5 ul samples of the resulting semi-quantitative RT-PCR products were resolved on a 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel and visualized using ethidium bromide. For analysis of stress- and hormone-responsive expression, real-time quantitative PCR was conducted using SYBR green (TaKaRa Biotechnology) on an IQ5 real time-PCR machine (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), with a final volume of 20 μl per reaction. Each reaction mixture contained 10.0 μl of SYBR Premix ExTaq II (TaKaRa Biotechnology), 1.0 μl of cDNA template, 0.8 μl of each primer (1.0 μM), and 7.4 μl of sterile distilled H2O. Each reaction was performed in triplicate. Cycling parameters were 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles at 95 °C for 5 s, and 60 °C for 30 s. Melting-curve analyses were performed using a program with 95 °C for 15 s and then a constant increase from 60 °C to 95 °C. Transcripts of the Malus elongation factor 1 alpha gene (EF-1α; DQ341381) were used to standardize the cDNA samples for different genes. Li62 had previously compared apple EF-1α, actin, and 18S rRNA as internal controls and found that EF-1α is more stable than the others as a reference gene under saline conditions. Three independent biological replications were performed for each experiment. The software IQ5 was used to analyze the relative expression levels using the normalized-expression method63, and the expression data from the quantitative RT-PCR were analyzed and visualized using the programs GeneSnap and Mev 4.8.153.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31572110), as well as the Program for Innovative Research Team of Grape Germplasm Resources and Breeding (2013KCT-25). We thank Ming-zhou Xie (Genedenovo Biotechnology Co, Ltd, Guangzhou, China) for providing editorial support for the synteny and MEME analysis. We thank PlantScribe (www.plantscribe.com) for editing this manuscript.

Author Contributions

X.W., H.G., J.Y. and H.G. designed the study. J.Y. and M.G. performed data analysis. J.Y., L.H. and Y.W. contributed to the qRT-PCR and RT-PCR analysis. X.W. and H.G. provided guidance for the whole study. J.Y., H.G. and X.W. wrote and revised the manuscript. Steve reviewed this manuscript. R.W. and C.G. assisted with the interpretation of the results and provided editorial support for the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00040-y

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiping Wang, Email: wangxiping@nwsuaf.edu.cn.

Hua Gao, Email: gaohua2378@163.com.

References

- 1.Yamasaki., et al. DNA-binding domains of plant-specific transcription factors: structure, function, and evolution. Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atchley WR, Terhalle W, Dress A. Positional dependence, cliques, and predictive motifs in the bHLH protein domain. J. Mol. Evol. 1999;48:501–516. doi: 10.1007/PL00006494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atchley WR, Fitch WM. A natural classification of the basic helix-loop-helix class of transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:5172–5176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pires N, Dolan L. Origin and diversification of basic-helix-loop-helix proteins in plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009;27:862–874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens JD, Roalson EH, Skinner MK. Phylogenetic and expression analysis of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor gene family: genomic approach to cellular differentiation. Differentiation. 2008;76:1006–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson KA, Lopes JM. Survey and summary: Saccharomyces cerevisiae basic helix-loop-helix proteins regulate diverse biological processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1499–1505. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.7.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ludwig SR, Habera LF, Dellaporta SL, Wessler SR. Lc, a member of the maize R gene family responsible for tissue-specific anthocyanin production, encodes a protein similar to transcriptional activators and contains the myc-homology region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:7092–7096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roig-Villanova., et al. Interaction of shade avoidance and auxin responses: a role for two novel atypical bHLH proteins. EMBO J. 2007;26:4756–4767. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leivar P, et al. The Arabidopsis phytochrome-interacting factor PIF7, together with PIF3 and PIF4, regulates responses to prolonged red light by modulating phyB levels. Plant Cell. 2008;20:337–352. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S, et al. Overexpression of PRE1 and its homologous genes activates Gibberellin-dependent responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47:591–600. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babitha KC, Vemanna RS, Nataraja KN, Udayakumar M. Overexpression of EcbHLH57 Transcription factor from Eleusine coracana L. in tobacco confers tolerance to salt, oxidative and drought stress. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin C, et al. Overexpression of a bHLH1 transcription factor of Pyrus ussuriensis confers enhanced cold tolerance and increases expression of stress-responsive genes. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:441. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang D, Dai W. Molecular characterization of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) genes that are differentially expressed and induced by iron deficiency in. Populus. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34:1211–1224. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser BN, et al. Characterization of an ammonium transport protein from the peribacteroid membrane of soybean nodules. Science. 1998;281:1202–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matus JT, et al. Isolation of WDR and bHLH genes related to flavonoid synthesis in grapevine (Vitisvinifera L.) Plant Mol. Biol. 2010;72:607–620. doi: 10.1007/s11103-010-9597-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komatsu M, Maekawa M, Shimamoto K, Kyozuka J. The LAX1 and FRIZZY PANICLE 2 genes determine the inflorescence architecture of rice by controlling rachis-branch and spikelet development. Dev. Biol. 2001;231:364–373. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W, et al. Regulation of Arabidopsis tapetum development and function by Dysfunctional Tapetum1 (DYT1) encoding a putative bHLH transcription factor. Development. 2006;133:3085–3095. doi: 10.1242/dev.02463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gremski K, Ditta G, Yanofsky MF. The HECATE genes regulate female reproductive tract development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2007;134:3593–3601. doi: 10.1242/dev.011510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorensen AM, et al. The Arabidopsis Aborted Microspores (AMS) gene encodes a MYC class transcription factor. Plant J. 2003;33:413–423. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Payne CT, Zhang F, Lloyd AM. GL3 encodes a bHLH protein that regulates trichome development in arabidopsis through interaction with GL1 and TTG1. Genetics. 2000;156:1349–1362. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.3.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morohashi K, et al. Participation of the Arabidopsis bHLH factor GL3 in trichome initiation regulatory events. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:736–746. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.104521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pillitteri LJ, Sloan DB, Bogenschutz NL, Torii KU. Termination of asymmetric cell division and differentiation of stomata. Nature. 2007;445:501–505. doi: 10.1038/nature05467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menand B, et al. An ancient mechanism controls the development of cells with a rooting function in land plants. Science. 2007;316:1477–1480. doi: 10.1126/science.1142618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Q, et al. Overexpression of MdbHLH104 gene enhances the tolerance to iron deficiency in apple. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14:1633–1645. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ledent V, Paquet O, Vervoort M. Phylogenetic analysis of the human basic helix-loop-helix proteins. Genome Biol. 2002;3:1–18. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-6-research0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, et al. Genome-wide analysis of basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factor family in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:1167–1184. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.080580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toledo-Ortiz G, Huq E, Quail PH. The Arabidopsis basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factor family. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1749–1770. doi: 10.1105/tpc.013839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carretero-Paulet L, et al. Genome-wide classification and evolutionary analysis of the bHLH family of transcription factors in Arabidopsis, poplar, rice, moss, and algae. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:1398–1412. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.153593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey PC, et al. Update on the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2497–2501. doi: 10.1105/tpc.151140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun XH, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Baltimore D. Id proteins Id1 and Id2 selectively inhibit DNA binding by one class of helix-loop-helix proteins. Mol. Cell Biol. 1991;11:5603–5611. doi: 10.1128/MCB.11.11.5603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Licausi F, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic analysis of the AP2/ERF superfamily in Vitis vinifera. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:7–19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo R, et al. Genome-wide identification, evolutionary and expression analysis of the aspartic protease gene superfamily in grape. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:1–18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holub EB. The arms race is ancient history in Arabidopsis, the wildfolwer. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:516–519. doi: 10.1038/35080508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qi T, et al. Regulation of jasmonate-induced leaf senescence by antagonism between bHLH subgroup IIIe and IIId factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2015;27:1634–1649. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang YH, Irving HR. Developing a model of plant hormone interactions. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011;6:494–500. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.4.14558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanstraelen M, Benkova E. Hormonal interactions in the regulation of plant development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012;28:463–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kenrick P, Crane PR. The origin and early evolution of plants on land. Nature. 1997;389:33–39. doi: 10.1038/37918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steemans P, et al. Origin and radiation of the earliest vascular land plants. Science. 2009;324:353. doi: 10.1126/science.1169659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heckman DS, et al. Molecular evidence for the early colonization of land by fungi and plants. Science. 2001;293:1129–1133. doi: 10.1126/science.1061457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vision TJ, Brown DG, Tanksley SD. The origins of genomic duplications in Arabidopsis. Science. 2000;290:2114–2117. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the auxin response factor (ARF) gene family in maize (Zea mays) Plant Growth Regul. 2011;63:225–234. doi: 10.1007/s10725-010-9519-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu G, Kong H. Divergence of duplicate genes in exon-intron structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:1187–1192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109047109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zuo K, Zhao J, Wang J, Sun X, Tang K. Molecular cloning and characterization of GhlecRK, a novel kinase gene with lectin-like domain from Gossypium hirsutum. DNA Seq. 2004;15:58–65. doi: 10.1080/1042517042000191454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie XB, et al. The bHLH transcription factor MdbHLH3 promotes anthocyanin accumulation and fruit colouration in response to low temperature in apples. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35:1884–1897. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng XM, et al. The cold-induced basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor gene MdCIbHLH1 encodes an ICE-like protein in apple. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao Q, et al. Overexpression of MdbHLH104 gene enhances the tolerance to iron deficiency in apple. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016;14:1633–1645. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song S, et al. The bHLH Subgroup IIId Factors Negatively Regulate Jasmonate-Mediated Plant Defense and Development. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao H, et al. A single amino acid substitution in IIIf subgroup of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor AtMYC1 leads to trichome and root hair patterning defects by abolishing its interaction with partner proteins in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:14109–14121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.280735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kulaeva ON, Prokoptseva OS. Recent advances in the study of mechanisms of action of phytohormones. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2004;69:233–247. doi: 10.1023/B:BIRY.0000022053.73461.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glazebrook J. Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005;43:205–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Finn RD, et al. The Pfam protein families’ database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D211–D222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Velasco R, et al. The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus × domestica Borkh) Nat. Genet. 2010;42:833–839. doi: 10.1038/ng.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guo C, et al. Evolution and expression analysis of the grape (Vitis vinifera L.) WRKY gene family. J. Exp. Bot. 2014;65:1513–1528. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun H, Fan HJ, Ling HQ. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the bHLH gene family in tomato. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-16-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larkin MA, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tamura K, et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of grape aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene superfamily. PloS One. 2012;7:e32153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang H, et al. Unraveling ancient hexaploidy through multiply-aqligned angiosperm gene maps. Genome Res. 2008;18:1944–1954. doi: 10.1101/gr.080978.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li X, et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene superfamily in apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013;71:268–282. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu JK. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2002;53:247–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.091401.143329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li J, et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the SBP-box family genes in apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013;70:100–114. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li C, et al. The mitigation effects of exogenous melatonin on salinity-induced stress in Malus hupehensis. J Pineal Res. 2012;53:298–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hou H, et al. Genomic organization, phylogenetic comparison and differential expression of the SBP-box family genes in grape. PloS One. 2013;8:e59358–e59358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.