Abstract

Background

The Food and Drug Administration can reduce the nicotine content in cigarettes to very low levels. This potential regulatory action is hypothesized to improve public health by reducing smoking, but may have unintended consequences related to weight gain.

Methods

Weight gain was evaluated from a double-blind, parallel, randomized clinical trial of 839 participants assigned to smoke one of six investigational cigarettes with nicotine content ranging from 0.4 mg/g to 15.8 mg/g or their own usual brand for six weeks. Additional analyses evaluated weight gain in the lowest nicotine content cigarette groups (0.4 mg/g and 0.4 mg/g, high tar) to examine effect of study product in compliant subjects as assessed by urinary biomarkers. Differences in outcomes due to gender were also explored.

Findings

There were no significant differences in weight gain when comparing the reduced nicotine conditions with the 15.8 mg/g control group across all treatment groups and weeks. However, weight gain at Week 6 was negatively correlated with nicotine exposure in the two lowest nicotine content cigarette conditions. Within the two lowest nicotine content cigarette conditions, both male and female smokers biochemically verified to be compliant on study product gained significantly more weight than non-compliant smokers and control groups.

Conclusions

The effect of random assignment to investigational cigarettes with reduced nicotine on weight gain was likely obscured by non-compliance with study product. Men and women who were compliant in the lowest nicotine content cigarette conditions gained 1.2 kg over six weeks, indicating weight gain is a likely consequence of reduced exposure to nicotine.

Keywords: harm reduction, nicotine, public policy

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use, primarily through cigarette smoking, is the leading cause of preventable mortality, resulting in over 480,000 deaths in the United States annually (1, 2). Nicotine is the primary addictive constituent in cigarettes, and in an effort to reduce the public health burden of smoking, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act gave the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authority to greatly reduce the nicotine content of cigarettes if doing so would improve public health (3). This policy falls in line with the hypothesis that the reduction of nicotine content in cigarettes to a level below an addictive or reinforcing threshold will suppress nicotine-seeking behaviors in smokers (4–6). In a recent study, we tested this hypothesis by investigating the effects of cigarettes varying in nicotine content on cigarettes smoked per day and nicotine dependence over a 6-week period (7). We found that smokers randomized to smoke very low nicotine content (VLNC) cigarettes containing 2.4 mg of nicotine per gram of tobacco and below for 6 consecutive weeks smoked fewer cigarettes and had lower levels of nicotine dependence compared to those randomized to smoke normal nicotine content cigarettes (NNC; 15.8 mg of nicotine per gram of tobacco) or their usual brand (7). These data support the reduction of nicotine in cigarettes as a strategy for improving smoking-related public health outcomes. However, to fully capture the public health impact of a potential nicotine reduction policy, it is also necessary to identify possible unintended consequences of nicotine reduction, so that policymakers and clinicians may attempt to mitigate them.

The relation between smoking cessation and weight gain is well established. Smokers weigh less than non-smokers and smoking cessation is typically accompanied by weight gain, on average, of 4.5 kg within a year of abstinence (8–10). As such, one consequence of a nicotine reduction policy may be weight gain among current smokers (11). Nicotine in cigarettes is likely responsible for the weight-reducing effects of smoking. Use of the transdermal nicotine patch or nicotine gum (12) during quit attempts attenuates cessation-induced weight gain, typically in a dose-related manner. Additionally, varenicline, a partial nicotinic agonist FDA-approved for smoking cessation, may offset weight gain among quitters during treatment (13). In rats, self-administration of nicotine results in suppression of body weight gain (14–16). Moreover, cessation of nicotine self-administration (14) or reduction of nicotine dose to levels below a reinforcing threshold (16) results in weight gain. Mice exposed to smoke from NNC cigarettes gained significantly less weight than those exposed to smoke from VLNC cigarettes (17). Taken together, evidence points to reductions in nicotine exposure as mediating cessation-induced weight gain, and thus, weight gain is a likely outcome of nicotine reduction (18).

The aim of this investigation was to examine the effect of an abrupt switch to use of VLNC cigarettes on weight among current smokers. A randomized double-blind, multi-site clinical trial of daily smokers (n=839) not interested in quitting was completed in which participants were assigned to smoke cigarettes varying in nicotine content for six weeks. Here, we evaluated if smoking reduced nicotine content cigarettes in this sample was associated with weight gain. Given the hypothesized primary role of nicotine exposure as the mechanism underlying weight gain and evidence that most participants use other products when randomized to VLNC cigarettes (19, 20), an important analysis focused on the relation between urinary biomarkers of nicotine exposure and weight gain. Furthermore, some evidence suggests that women are more likely to use smoking as a method of weight control and may be more susceptible to post-cessation weight gain (21, 22); therefore, differences in outcomes due to gender were also explored.

METHODS

Participants

Adult daily smokers were recruited using flyers, direct mailings, television and radio, and other advertisements across 10 sites between 2013 and 2014. Inclusion criteria included: at least 18 years of age, at least five cigarettes smoked per day, expired carbon monoxide (CO) greater than 8 ppm or urinary cotinine greater than 100 ng/ml. Exclusion criteria were: intention to quit smoking in the next 30 days; use of other tobacco products on more than 9 of the past 30 days; serious psychiatric or medical condition; positive toxicological screen for illicit drug use other than cannabis; pregnancy, plans to become pregnant, or breastfeeding; and exclusive use of “roll your own” cigarettes. All 839 eligible participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The study was approved by accredited Institutional Review Boards at each participating site, and written informed consent was obtained from each study volunteer. All study procedures were conducted in compliance with research ethics outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Design

The seven-group, double-blind, randomized trial included a screening visit, a 2-week baseline period during which participants smoked their own usual brand cigarettes, and a 6-week investigational cigarette use period. During the 6-week experimental period, participants were provided with one of seven types of cigarettes varying in nicotine content (mg nicotine per g of tobacco): 0.4 mg/g; 0.4 mg/g high tar (HT); 1.3 mg/g; 2.4 mg/g; 5.2 mg/g; 15.8 mg/g, and usual brand (UB). Average tar yields were 8 to 10 mg; however, for the high tar cigarettes it was 13 mg. The 0.4 HT condition, which contained tobacco filler with the same nicotine content, but differed from 0.4 mg/g cigarettes in filter and ventilation resulting in higher yield (ISO) of tar and nicotine, was added to the design to explore the impact of tar yield on the use and acceptability of VLNC cigarettes. A two-week supply of cigarettes was provided free of charge at each weekly session during the experimental period. During this time, participants were instructed to smoke only the provided investigational cigarettes and received counseling aimed to increase compliance, though there was no penalty for using other nicotine/tobacco products. Study design is described in greater detail in the primary study manuscript (7).

Study Assessments & Laboratory Analyses

During each visit to the laboratory, participants were asked to remove shoes and outerwear, and to plant both feet firmly and evenly on the scale surface. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg. Biomarkers of nicotine exposure were assessed from urine samples collected at randomization, Week 2, and Week 6. Urinary total nicotine equivalents (TNE), the sum of nicotine and its metabolites and a measure of daily nicotine exposure, were analyzed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (23–25). Saliva samples for the assessment of nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR), an indicator or CYP2A6 activity and the rate of nicotine metabolism, were collected during the second baseline session (7).

Statistical Analyses

Our initial comparison focused on differences in weight gain (defined as each participant’s weight at each visit minus his or her baseline weight in kg) by randomized treatment assignment. Baseline weight was the average of three measurements taken at screening and the two, weekly baseline visits. Two participants were found to have a 50kg weight gain at the six-week follow-up period. These records are assumed to have been a data entry error and were removed from all analyses. Differences in weight gain over time were analyzed using a linear mixed model with a random intercept to account for multiple observations from a single individual. Fixed-effects included in the model were treatment group, visit, treatment by visit interaction, baseline weight, age, gender, race, the natural log of salivary NMR, site, time-of-year at enrollment and a site by time-of-year at enrollment interaction. Time-of-year at enrollment was included in the model by mapping the calendar onto a circle and translating the date into radians and was included as time-of-year impacts weight gain (26). A Bonferroni-adjusted p-value of 0.01 was used to conclude statistical significance when comparing treatment groups to the 15.8 mg/g control. A secondary comparison was also completed, which compared treatment groups to the Usual Brand control condition.

Within this study population, the average reduction in biomarkers of tobacco use was less than expected given the reduction in nicotine content of the study cigarettes (7), indicating likely use of other sources of nicotine (e.g., non-study cigarettes). The use of other nicotine-containing products could potentially mask an effect of the use of VLNC cigarettes on weight gain. Thus, we conducted a subgroup analysis comparing weight gain by compliance status in the combined 0.4 mg/g and 0.4 mg/g HT groups. Compliance status was dichotomized and a participant was considered compliant if their urinary TNE was less than 6.41 nmol/ml at Week 2 and Week 6. This cutoff was established in a prior study in which compliance with 0.4 mg/g cigarettes was enforced (27). Biochemical confirmation of compliance was not possible in the other cigarette conditions because individual differences in nicotine intake from these cigarettes likely result in greater overlap in the distribution of TNE with smoking NNC cigarettes and no data are available validating such a cutoff. Weight-gain was compared by compliance status over time using a linear mixed-model with a random intercept and fixed-effects for compliance status, visit, compliance status by visit interaction, baseline weight, age, gender, race, baseline cigarettes per day (CPD), natural log of baseline TNE, study site and time-of-year at randomization. Baseline CPD and baseline TNE were previously shown to be associated with biochemical measures of non-compliance and were included in this model to account for potential confounding (20). Gender was examined as a moderator by adding an interaction for gender and estimating treatments effects within each gender. Finally, the association between weight gain and the natural log of TNE, as the raw TNE data were not normally distributed, at Week 6 in the 0.4 mg/g and 0.4 mg/g HT groups was summarized by Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

The overall sample was 41.7 ± 13.2 years old, 57.3% male, smoked 15.6 ± 7.6 CPD, and weighed 85.8 ± 21.8 kg at baseline. Retention exceeded 92% and attrition did not differ by cigarette group. Additional baseline sample characteristics can be accessed in the primary report of these data (7).

Cigarette condition failed to significantly impact weight gain

Mean changes in body weight (kg) comparing between each investigational cigarette condition and each of the two control conditions (15.8 mg/g and Usual Brand groups) by week for the entire study sample are shown in Table 1. With the exception of the 0.4 mg/g HT group at Week 4 (p = 0.009), there were no significant differences in weight gain when comparing the reduced nicotine conditions with the 15.8 mg/g control group across all treatments groups and week.

Table 1.

Effect of smoking reduced nicotine content cigarette on weight gain (kg) over six weeks.

| Treatment Group | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15.8 mg group as reference group (primary analysis): | ||||||

| 5.2 mg/g | 0 (−0.48, 0.48) | 0.29 (−0.2, 0.77) | 0.01 (−0.47, 0.5) | 0.13 (−0.36, 0.62) | 0.14 (−0.36, 0.63) | 0.01 (−0.48, 0.49) |

| 2.4 mg/g | 0.01 (−0.47, 0.5) | 0.34 (−0.15, 0.83) | 0.08 (−0.41, 0.58) | 0.24 (−0.26, 0.73) | 0.37 (−0.13, 0.87) | 0.22 (−0.27, 0.71) |

| 1.3 mg/g | 0.2 (−0.28, 0.68) | 0.52 (0.03, 1) | 0.25 (−0.24, 0.73) | 0.16 (−0.34, 0.65) | 0.22 (−0.27, 0.71) | 0.18 (−0.3, 0.67) |

| 0.4 mg/g | 0.1 (−0.39, 0.59) | 0.36 (−0.13, 0.85) | 0.11 (−0.39, 0.6) | 0.28 (−0.22, 0.77) | 0.34 (−0.16, 0.83) | 0.18 (−0.32, 0.67) |

| 0.4 mg/g (HT) | 0.11 (−0.38, 0.59) | 0.51 (0.03, 0.99) | 0.23 (−0.25, 0.72) | 0.65* (0.16, 1.14) | 0.33 (−0.16, 0.82) | 0.12 (−0.36, 0.6) |

| Usual Brand group as reference group (secondary analysis): | ||||||

| 15.8 mg/g | −0.06 (−0.55, 0.42) | −0.04 (−0.53, 0.45) | −0.14 (−0.63, 0.35) | −0.16 (−0.65, 0.33) | −0.43 (−0.92, 0.06) | −0.2 (−0.69, 0.29) |

| 5.2 mg/g | −0.07 (−0.55, 0.42) | 0.25 (−0.24, 0.73) | −0.13 (−0.62, 0.36) | −0.03 (−0.52, 0.46) | −0.3 (−0.79, 0.2) | −0.19 (−0.68, 0.29) |

| 2.4 mg/g | −0.05 (−0.53, 0.44) | 0.3 (−0.18, 0.79) | −0.06 (−0.55, 0.44) | 0.08 (−0.42, 0.57) | −0.06 (−0.56, 0.44) | 0.02 (−0.47, 0.51) |

| 1.3 mg/g | 0.14 (−0.34, 0.62) | 0.48 (0, 0.96) | 0.1 (−0.38, 0.59) | 0 (−0.49, 0.49) | −0.21 (−0.7, 0.28) | −0.02 (−0.5, 0.47) |

| 0.4 mg/g | 0.04 (−0.45, 0.52) | 0.32 (−0.17, 0.81) | −0.04 (−0.53, 0.46) | 0.12 (−0.38, 0.61) | −0.09 (−0.59, 0.4) | −0.02 (−0.52, 0.47) |

| 0.4 mg/g (HT) | 0.04 (−0.44, 0.52) | 0.47 (−0.01, 0.95) | 0.09 (−0.39, 0.57) | 0.49 (0.01, 0.97) | −0.1 (−0.59, 0.38) | −0.08 (−0.56, 0.4) |

indicates p < 0.01.

Mean differences (95% confidence interval) are reported.

Reduced nicotine exposure resulted in significant weight gain

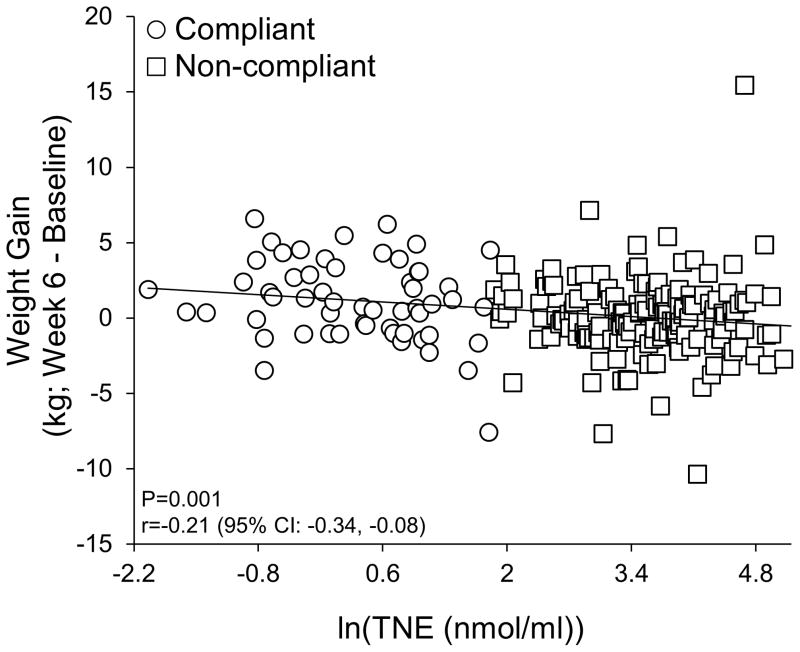

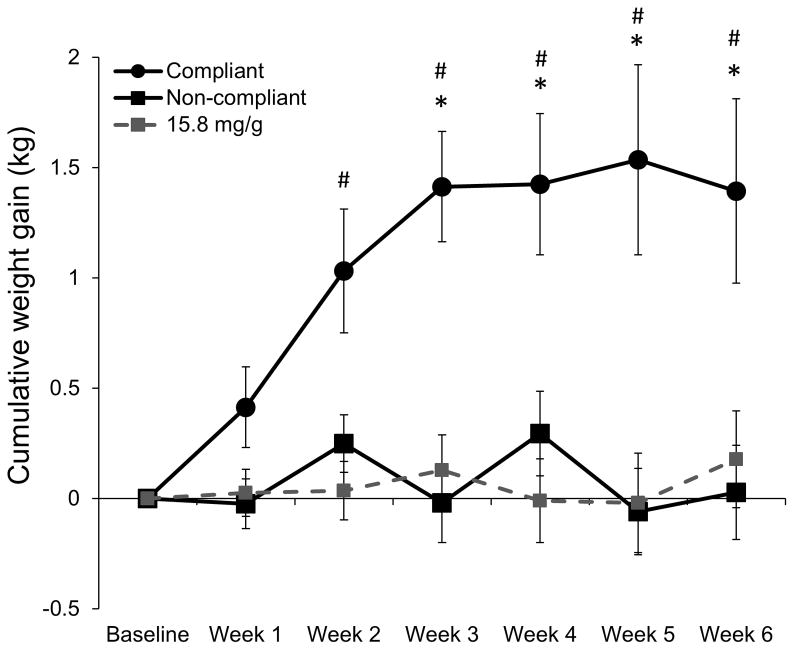

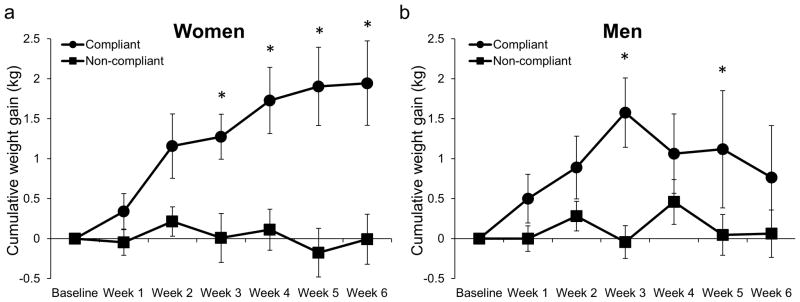

Weight gain was significantly negatively correlated with nicotine exposure in the two lowest nicotine content cigarette conditions (0.4 mg/g and 0.4 mg/g HT; r = −0.21, p = 0.001, 95% CI: −0.34, −0.08; Figure 1). Within the two lowest nicotine content cigarette conditions, smokers compliant with the investigational cigarettes (n = 45) gained significantly more weight than non-compliant smokers (n = 170), the 15.8 mg/g control group (n = 119) and the Usual Brand group (n = 118) beginning at Week 3 (Figure 2). Women compliant on study product (n = 24) gained significantly more weight than non-compliant women (n = 76) and women in the 15.8 mg/g control group (n = 48) and Usual Brand group (n = 46) (Figure 3a). Likewise, men compliant on study product (n = 21) gained significantly more weight than non-compliant men (n = 94) and men in the 15.8 mg/g group (n = 71) and Usual Brand group (n = 72) (Figure 3b). There was no significant interaction between gender and compliance on weight gain.

Figure 1. Relationship between weight gain and nicotine exposure.

Within 0.4 mg/g and 0.4 mg/g HT groups, weight gain was negatively correlated with the natural log of TNE.

Figure 2. Weight gain over time in compliant and non-compliant individuals randomized to 0.4 mg/g and 0.4 mg/g HT cigarettes.

Mean cumulative weight gain in individuals compliant (urinary TNE less than 6.41 nmol/ml at Week 2 and Week 6) or non-compliant (urinary TNE greater than 6.4 at Week 2 or Week 6) on 0.4 mg/g and 0.4 mg/g HT cigarettes, and 15.8 mg/g control group. * indicates P<0.01 comparing compliant and non-compliant groups. # indicates P<0.01 comparing compliant and 15.8 mg/g groups. + indicates P<0.1 comparing compliant and usual brand groups.

Figure 3. Weight gain over time in compliant and non-compliant men and women randomized to 0.4 mg/g and 0.4 mg/g HT cigarettes.

Mean cumulative weight gain in women (a) and men (b) compliant (urinary TNE less than 6.41 nmol/ml at Week 2 and Week 6) or non-compliant (urinary TNE greater than 6.4 at Week 2 or Week 6) on 0.4 mg/g and 0.4 mg/g HT cigarettes, and 15.8 mg/g control group. * indicates P<0.01 comparing compliant and non-compliant groups.

DISCUSSION

The implementation of product standards requiring substantial reductions in nicotine content in cigarettes is hypothesized to improve public health by facilitating cessation of smoking. However, the reduction of nicotine content in cigarettes may have other unintended health-related outcomes. The current investigation found that although there was no impact of random assignment to reduced nicotine content investigational cigarettes on weight gain, compliance with investigational cigarettes containing only 2–3% of the nicotine found in NNC cigarettes was associated with significant weight gain. Furthermore, among individuals smoking cigarettes with the lowest nicotine content, weight gain was negatively correlated with biomarkers of nicotine exposure. These results have important implications for product standards on nicotine and the understanding of nicotine on body weight regulation. The reduction of nicotine content in cigarettes results in an expected amount of weight gain and would likely be observed if product standards requiring low nicotine levels in cigarettes are enacted, assuming people do not substitute other nicotine-containing products.

Compliant participants in the VLNC cigarette condition gained approximately 1.4 kg over 6 weeks of smoking VLNC cigarettes, which is comparable to weight gain reported among abstinent smokers over a similar time period (28, 29). In the current study, weight gain among compliant smokers occurred primarily within the first three weeks of VLNC use, and then plateaued. This is reassuring, as it suggests that weight gain following reductions in nicotine exposure might be expected to be consistent with long term changes in weight gain following cessation. Further support for this notion is provided by a study that reported significant body weight gain (approximately 2 kg) in self-reported compliant smokers of cigarettes with nicotine content that was gradually reduced after 26 weeks (18). Therefore, it is reasonable to expect long term weight gain following nicotine reduction to be similar to that observed in cessation, assuming no use of other nicotine-containing products. A meta-analysis of 62 studies focused on cessation-induced weight gain reported a curvilinear pattern of weight gain over 12 months in untreated abstinent smokers, with weight gain reaching approximately 4.5 kg and plateauing after approximately six months (10). Further, the rate of weight gain in former smokers returns to that of age-matched non-smoker controls following one year of smoking cessation (9). Veldheer et al (8) recently reported a positive correlation between CPD prior to quitting and ten-year post-cessation weight gain, indicating that a larger change in nicotine exposure results in more robust weight gain. Of note, the sample in the current report was overweight at baseline. Obese and overweight smokers consume more CPD on average than normal weight smokers (8, 11), and therefore may be at risk for larger weight gain following nicotine reduction (8). Although cessation is associated with an overall increase in weight gain, the impact of quitting on weight gain varies, with approximately 16% of smokers losing weight and 10% gaining over 10 kg in one year (10). The same variability might be expected population-wide following nicotine reduction in cigarettes. Future studies testing the impact of VLNC cigarette use on weight and weight-related health outcomes over longer time periods may confirm this and should more fully capture the impact of nicotine reduction on body weight and health.

Despite the likelihood of weight gain in smokers following nicotine reduction, the overall public health impact of reducing nicotine in cigarettes may be positive if nicotine reduction increases smoking cessation (4, 7, 11). Indeed, smoking cessation is widely recommended despite the expected gain in weight because the health benefits of quitting far outweigh the negative health consequences of post-cessation weight gain (30). It is possible that nicotine content could be reduced to a level that would support quitting without resulting in weight gain. However, the lowest nicotine content cigarette tested most reliably decreased multiple measures of dependence and increased quit attempts (7), putative predictors of a positive public health impact, even if accompanied by weight gain. There is no indication that the amount of weight gain expected during use of VLNC cigarettes would exceed that of other means of quitting without pharmacotherapy. Research is warranted to determine if NRTs (12, 31, 32), varenicline (13), or bupropion (22), which attenuate post-cessation weight gain, would similarly mitigate the weight gain observed in smokers of VLNC cigarettes.

Women more frequently report using smoking as a weight-control method and report fear of weight gain following quitting (21, 33). Some studies report that post-cessation weight gain is greater among women than men (33, 34), but there are also contradictory findings (10). Our study did not reveal significant gender differences, though we did find that women gained more weight on average than men following reductions in nicotine exposure. Additionally, weight gain at Week 3 was equal for women and men, but then plateaued in women and decreased in men. Women were more likely to be compliant on VLNC study product (20), and within the compliant group, nicotine exposure was lower in women than men (natural log of TNE ± SEM: 0.08 ± 0.17 in women; and 0.43 ± 0.20 in men). The lower levels of nicotine exposure among women may contribute to the higher average weight gain reported here. Sample size was low and future experiments with sufficient power to address gender differences in weight gain are warranted.

In addition to the results of this study clarifying the effect of VLNC cigarettes on weight gain, it was demonstrated that urinary biomarkers of product compliance can allow for evaluating potential unintended consequences of nicotine reduction where non-compliance could otherwise occlude an effect. Indeed, differences in compliance likely both reduce potential effect size and add substantial variance to measures of unintended consequences related to reduced nicotine exposure per se. An important limitation of focusing on just compliant participants is that they self-selected into compliant and non-compliant groups, which may introduce confounds. Biomarkers of compliance might be utilized to incentivize compliance on study product to better our understanding of the effects of a potential product standard on behavior and health.

These data contribute important information to tobacco regulatory science and provide a greater understanding of the impact of nicotine on body weight regulation. The magnitude of weight gain is negatively related to nicotine exposure, and is similar to what is observed following smoking cessation. Given these results, weight gain is an expected outcome of the implementation of product standards mandating reduced nicotine content in cigarettes. Under the assumption that reductions in nicotine exposure leads to decreased dependence and therefore, increased quitting (7), the positive public health impact of product standards mandating reductions in nicotine content in cigarettes are likely to outweigh the negative health consequence of weight gain (30). Nonetheless, the potential for weight gain must be considered when assessing the public health impact of product standards requiring the reduction of nicotine content in cigarettes. Furthermore, the long-term effect of this strategy must be considered in future research with the goal of mitigating potential weight gain following implementation of product standards reducing nicotine levels in cigarettes.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

Evidence suggests that the reduction of nicotine content in cigarettes may reduce the public health burden of smoking by increasing quitting.

Smoking cessation results in weight gain, an effect attributed to nicotine; however, the impact of smoking very low nicotine content cigarettes on weight has received little attention.

The data presented within this manuscript demonstrate that smoking very low nicotine cigarettes results in weight gain comparable to cessation. Future work should develop strategies that minimize weight gain during use of very low nicotine content cigarettes.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this paper was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products (U54DA031659). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or Food and Drug Administration. The authors would like to thank: Paul Cinciripini, Steve Hecht, Joni Jensen, Tonya Lane, Sharon Murphy, Jason Robinson, Maxine Stitzer, Andrew Strasser, Hilary Tindle, and all the students, fellows and staff involved in the Center for the Evaluation of Nicotine in Cigarettes.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged >/=18 years--United States, 2005–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1207–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Study Group on Tobacco Product R. WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation. Report on the scientific basis of tobacco product regulation: fifth report of a WHO study group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, (2009).

- 4.Benowitz NL, Henningfield JE. Establishing a nicotine threshold for addiction. The implications for tobacco regulation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:123–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407143310212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donny EC, Taylor TG, LeSage MG, et al. Impact of tobacco regulation on animal research: new perspectives and opportunities. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:1319–38. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatsukami DK, Benowitz NL, Donny E, Henningfield J, Zeller M. Nicotine reduction: strategic research plan. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1003–13. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donny EC, Denlinger RL, Tidey JW, et al. Randomized Trial of Reduced-Nicotine Standards for Cigarettes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1340–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1502403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veldheer S, Yingst J, Zhu J, Foulds J. Ten-year weight gain in smokers who quit, smokers who continued smoking and never smokers in the United States, NHANES 2003–2012. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015 doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Audrain-McGovern J, Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking, nicotine, and body weight. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:164–8. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aubin HJ, Farley A, Lycett D, Lahmek P, Aveyard P. Weight gain in smokers after quitting cigarettes: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e4439. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rupprecht LE, Donny EC, Sved AF. Obese smokers as a potential subpopulation of risk in tobacco reduction policy. Yale J Biol Med. 2015 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross J, Stitzer ML, Maldonado J. Nicotine replacement: effects of postcessation weight gain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:87–92. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nides M, Oncken C, Gonzales D, et al. Smoking cessation with varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist: results from a 7-week, randomized, placebo- and bupropion-controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1561–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunney PE, Burroughs D, Hernandez C, LeSage MG. The effects of nicotine self-administration and withdrawal on concurrently available chow and sucrose intake in adult male rats. Physiol Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Dell LE, Chen SA, Smith RT, et al. Extended access to nicotine self-administration leads to dependence: Circadian measures, withdrawal measures, and extinction behavior in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:180–93. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.105270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rupprecht LE, Smith TT, Donny EC, Sved AF. Self-Administered Nicotine Suppresses Body Weight Gain Independent of Food Intake in Male Rats. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abreu-Villaca Y, Filgueiras CC, Guthierrez M, et al. Exposure to tobacco smoke containing either high or low levels of nicotine during adolescence: differential effects on choline uptake in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:776–80. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benowitz NL, Dains KM, Hall SM, et al. Smoking behavior and exposure to tobacco toxicants during 6 months of smoking progressively reduced nicotine content cigarettes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:761–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benowitz NL, Nardone N, Hatsukami DK, Donny EC. Biochemical estimation of noncompliance with smoking of very low nicotine content cigarettes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:331–5. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nardone N, Donny EC, Hatsukami D, et al. Estimations and Predictors of Non-Compliance in Switchers to Reduced Nicotine Content Cigarettes. Addiction. doi: 10.1111/add.13519. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine MD, Perkins KA, Marcus MD. The characteristics of women smokers concerned about postcessation weight gain. Addict Behav. 2001;26:749–56. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farley AC, Hajek P, Lycett D, Aveyard P. Interventions for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD006219. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006219.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carmella SG, Ming X, Olvera N, et al. High throughput liquid and gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assays for tobacco-specific nitrosamine and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites associated with lung cancer in smokers. Chem Res Toxicol. 2013;26:1209–17. doi: 10.1021/tx400121n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy SE, Park SS, Thompson EF, et al. Nicotine N-glucuronidation relative to N-oxidation and C-oxidation and UGT2B10 genotype in five ethnic/racial groups. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:2526–33. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy SE, Wickham KM, Lindgren BR, Spector LG, Joseph A. Cotinine and trans 3′-hydroxycotinine in dried blood spots as biomarkers of tobacco exposure and nicotine metabolism. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2013;23:513–8. doi: 10.1038/jes.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le CT, Liu P, Lindgren BR, Daly KA, Scott Giebink G. Some statistical methods for investigating the date of birth as a disease indicator. Stat Med. 2003;22:2127–35. doi: 10.1002/sim.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denlinger RL, Smith TT, Murphy SE, et al. Nicotine and Anatabine Exposure from Very Low Nicotine Content Cigarettes. Tob Reg Sci. 2016;2:186–203. doi: 10.18001/TRS.2.2.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klesges RC, Meyers AW, Klesges LM, La Vasque ME. Smoking, body weight, and their effects on smoking behavior: a comprehensive review of the literature. Psychol Bull. 1989;106:204–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emont SL, Cummings KM. Weight gain following smoking cessation: a possible role for nicotine replacement in weight management. Addict Behav. 1987;12:151–5. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnoll RA, Wileyto EP, Lerman C. Extended duration therapy with transdermal nicotine may attenuate weight gain following smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 2012;37:565–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen SS, Hatsukami D, Brintnell DM, Bade T. Effect of nicotine replacement therapy on post-cessation weight gain and nutrient intake: a randomized controlled trial of postmenopausal female smokers. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Filozof C, Fernandez Pinilla MC, Fernandez-Cruz A. Smoking cessation and weight gain. Obes Rev. 2004;5:95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williamson DF, Madans J, Anda RF, et al. Smoking cessation and severity of weight gain in a national cohort. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:739–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103143241106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]