Abstract

Hyperinsulinaemia, obesity and dyslipidaemia are independent and collective risk factors for many cancers. Here, the long-term effects of a 23% Western high-fat diet (HFD) in two immunodeficient mouse strains (NOD/SCID and Rag1 −/−) suitable for engraftment with human-derived tissue xenografts, and the effect of diet-induced hyperinsulinaemia on human prostate cancer cell line xenograft growth, were investigated. Rag1 −/−and NOD/SCID HFD-fed mice demonstrated diet-induced impairments in glucose tolerance at 16 and 23 weeks post weaning. Rag1 −/− mice developed significantly higher fasting insulin levels (2.16 ± 1.01 ng/ml, P = 0.01) and increased insulin resistance (6.70 ± 1.68 HOMA-IR, P = 0.01) compared to low-fat chow-fed mice (0.71 ± 0.12 ng/ml and 2.91 ± 0.42 HOMA-IR). This was not observed in the NOD/SCID strain. Hepatic steatosis was more extensive in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice compared to NOD/SCID mice. Intramyocellular lipid storage was increased in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice, but not in NOD/SCID mice. In Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice, LNCaP xenograft tumours grew more rapidly compared to low-fat chow-fed mice. This is the first characterisation of the metabolic effects of long-term Western HFD in two mouse strains suitable for xenograft studies. We conclude that Rag1 −/− mice are an appropriate and novel xenograft model for studying the relationship between cancer and hyperinsulinaemia.

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome encompasses obesity and several related conditions, including insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease1. While these comorbidities are intrinsically linked2–4, some are independent risk factors for cancer5–7. Many components of metabolic syndrome promote gastrointestinal, endometrial, breast, and prostate cancers and increase the likelihood of lethal, higher-grade disease8–11. Despite growing recognition of the strong link between metabolic disturbance and cancer progression, there are few engraftable rodent models of human cancer suitable for investigating this association. A number of mouse models of obesity, hyperinsulinaemia, and hyperglycaemia arose from spontaneous genetic mutations12. This includes leptin-deficient (Lep° b/ ° b)13, leptin receptor-deficient (LepR db/db)14, and agouti yellow obese mice (A y /a)15. Diet-induced models of metabolic syndrome have also been developed. Consuming a high-fat diet (HFD) induces obesity with insulin resistance in rats16, 17, and a high-fat, high-simple carbohydrate diet models human type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in C57BL/6 J mice18.

As inflammation is involved in the development of metabolic syndrome19, most studies of diet-induced obesity employ immunocompetent mice, such as the C57BL/6 J strain12 which develops insulin insensitivity as a result of chronic inflammation when fed a 42 or 60% HFD20, 21. Some immunodeficient strains, including severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID), and NOD/SCIDIL2Rγ (NSG) mice, may be resistant to developing HFD-induced metabolic syndrome, due to a lack of adaptive immunity and defective innate immunity22, 23. For example, NOD/SCID mice, which are immunocompromised due to a spontaneous mutation in Prkdc 24, develop streptozotocin-induced, but not diet-induced hyperglycaemia25. Streptozotocin-induced pancreatic insulitis, a well-established model of type I diabetes mellitus, destroys pancreatic β-cell function, thereby abrogating insulin secretion. This model does not recapitulate the complex interplay between hyperinsulinaemia, β-cell stress and apoptosis, and insulin resistance phenotype of T2DM, however26. In contrast, mice with inactivating mutations in the genes encoding the RAG1 or RAG2 proteins, Rag1 and Rag2, are susceptible to diet-induced hyperglycaemia20, 21, 27. RAG1 and RAG2 are involved in activating the recombination of T-cell receptor molecules and immunoglobulin genes, and a null mutation of either of these genes results in adaptive immunity deficiencies, with an absence of mature B and T lymphocytes28. Rag1 −/− mice backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 J genetic background rapidly develop insulin resistance one week after initiation of 60% HFD feeding20. Additionally, when fed a 42% fat diet, Rag1 −/− mice on a C57BL/6 J background gain more weight and fat mass than wild-type C57BL/6 J mice. Both Rag1 −/−and wild-type C57BL/6 J mice exhibit glucose and insulin intolerance after 10 weeks on this diet21. SCID, NOD/SCID and NSG mice are often employed in xenograft studies, as the rate of xenograft establishment is high for many cancer cell lines29. These strains are resistant to diet-induced insulin resistance30, and therefore, are not suitable for studying tumour biology associated with hyperinsulinaemia.

The aim of our study was to develop a diet-induced model of hyperinsulinaemia in immunocompromised mice suitable for cancer xenograft studies. In order to confirm previous studies22, 23, and to determine if Rag1 −/− mice provide a better engraftable model for metabolic dysfunction, we compared the effect of a normal, low-fat chow and a Western, moderate-fat diet (23% fat diet, 45% digestible energy from fat) on weight gain, glucose tolerance, hormone levels and adiposity in Rag1 −/− mice (on a C57BL/6 J background) and NOD/SCID mice. This study is the first to show that a Western HFD results in more significant diet-induced metabolic dysfunction in Rag1 −/− mice compared to NOD/SCID HFD-fed mice. Furthermore, a pilot study demonstrates that LNCaP human prostate cancer cell line xenografts grow more rapidly in Rag1 −/− mice fed a Western HFD than tumours in control Rag1 −/− mice fed a low-fat diet. The Rag1 −/− mouse, therefore, provides a novel model for studying tumour biology associated with diet-induced hyperinsulinaemia.

Results

Effect of a high-fat diet on NOD/SCID and Rag1−/− mice

Glucose tolerance, insulin levels and HOMA analysis

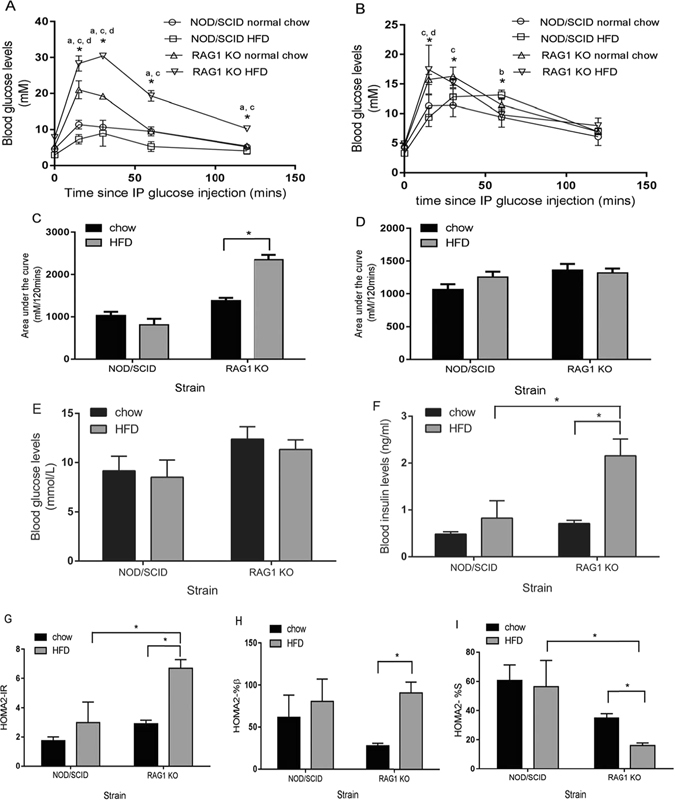

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests (IPGTT) were conducted 16 and 23 weeks after diet initiation in Rag1 −/− and NOD/SCID mice to determine the effect of HFD (23% fat) on glucose tolerance (Fig. 1A,B). Blood glucose levels were elevated (AUC analysis, 2345 ± 116 mM/120 mins) in Rag1 −/− mice fed a HFD for 16 weeks, compared to Rag1 −/− mice fed low-fat chow (1380 ± 67.61 mM/120 mins, P = 0.001), and higher blood glucose levels were observed in HFD-fed mice at all time points (Fig. 1A) (P ≤ 0.05). After 23 weeks, glucose tolerance improved in the HFD-fed Rag1 −/− mice (AUC 1319 mM/120 ± 66.89 mins at 23 weeks post-weaning, relative to the 16-week time point) (Fig. 1C,D). In low-fat chow-fed Rag1 −/− mice, however, glucose tolerance remained stable at 16 (AUC 1380 mM/120 mins ± 67.61) and 23 weeks post-weaning (AUC 1362 mM/120 mins ± 94.18) (Fig. 1C,D).

Figure 1.

The effects of high-fat diet (HFD) or low-fat chow on blood glucose and insulin levels, insulin resistance, and insulin sensitivity in Rag1 −/− and NOD/SCID mice. (A) Glucose tolerance (IPGTT) is impaired 16 weeks post-weaning in 23% high-fat diet (HFD) fed Rag1 −/− mice (n = 8) compared to Rag1 −/− mice fed low-fat chow (n = 4), and NOD/SCID mice fed HFD (n = 8), or low-fat chow (n = 4). (B) Glucose tolerance (IPGTT) is improved 23 weeks after diet initiation in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice, while glucose tolerance is impaired in NOD/SCID mice fed HFD. (C) Blood glucose levels (measured over 120 minutes of IPGTT and expressed as area under the curve) in Rag1 −/− and NOD/SCID mice fed low-fat chow or HFD at 16 weeks. (D) Blood glucose levels (measured over 120 minutes of IPGTT and expressed as area under the curve) at 23 weeks post diet initiation. (E) Fasting blood glucose levels measured at 28 weeks post-weaning. (F) Fasting insulin levels (ELISA) measured 28 weeks after diet initiation are significantly higher in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice compared to Rag1 −/− mice fed low-fat chow and NOD/SCID HFD-fed mice. (G) Insulin resistance, (Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance, HOMA-IR) is significantly higher in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice. (H) Steady-state β-cell function determined by Homeostatic model assessment for β-cell function (HOMA-β) is significantly higher in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice. (I) Insulin sensitivity, estimated using Homeostatic model assessment for (HOMA-S), is significantly lower in Rag1 −/− mice on a HFD. Mean + SEM. Two-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test *P ≤ 0.05. a = Rag1 −/− HFD vs. Rag1 −/− low-fat chow-fed mice, b = NOD/SCID HFD-fed vs. NOD/SCID low-fat chow-fed mice, c = Rag1 −/− HFD vs. NOD/SCID HFD-fed mice, d = Rag1 −/− low-fat chow vs. NOD/SCID low-fat chow-fed mice. All other data was tested for statistical significance using the Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney test. *P ≤ 0.05.

Glucose tolerance in HFD-fed NOD/SCID mice was more impaired at 23 weeks (AUC 1256 mM/120 ± 81.0 mins) (Fig. 1D) than at 16 weeks (810 ± 143.5 mM/120 mins) (Fig. 1C). Glucose levels were elevated at the 30 and 60 min time points at 23 weeks (P = 0.042) (Fig. 1B). No significant differences in glucose tolerance were observed between 16 (1028 ± 89.5 mM/120 mins) and 23 weeks post-weaning (1064 ± 81.15 mM/120 mins) in NOD/SCID low-fat chow-fed mice (Fig. 1C,D).

In mice fed a high-fat diet, blood glucose levels were significantly lower in NOD/SCID mice compared to Rag1 −/− mice (P = 0.026) at 16 weeks (Fig. 1A). Similarly, on low-fat chow diet, NOD/SCID mice had significantly lower blood glucose levels compared to Rag1 −/− mice at the 15 and 30 minute GTT time points at 16 (P = 0.026) and 23 weeks (P = 0.026) (Fig. 1A,B). Blood glucose levels were significantly higher in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice compared to NOD/SCID HFD-fed mice at the 15-minute GTT time point at 23 weeks (P = 0.026) (Fig. 1B).

Fasting blood glucose and insulin were determined at endpoint (28 weeks post-weaning) in order to estimate insulin resistance, insulin sensitivity and steady-state β-cell function using HOMA231, 32. Fasting insulin levels were significantly higher in Rag1 −/− mice fed HFD (2.16 ± 1.01 ng/ml) compared to low-fat chow-fed Rag1 −/− (0.712 ± 0.116 ng/ml, P = 0.012), and compared to NOD/SCID HFD-fed mice (P = 0.028) (Fig. 1F). No significant difference was observed between NOD/SCID groups (Fig. 1F). HOMA insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was significantly greater in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice (6.70 ± 1.68) compared to low-fat chow-fed controls (2.91 ± 0.42, P = 0.012) (Fig. 1G), but not affected by diet in NOD/SCID mice. Higher levels of insulin resistance were observed in HFD-fed Rag1 −/− mice compared to NOD/SCID HFD-fed mice (P = 0.032). Similarly, steady-state β-cell function (HOMA-β) (Fig. 1H) was significantly higher in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice (90.7 ± 35.8) compared to low-fat chow-fed mice (27.87 ± 5.00) (P = 0.012). Insulin sensitivity (HOMA-S) was significantly lower in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice (15.97 ± 4.88) compared to low-fat chow-fed Rag1 −/− mice (34.90 ± 5.31, P = 0.012) and HFD-fed NOD/SCID mice (P = 0.032) (Fig. 1I). No significant difference was observed between NOD/SCID groups.

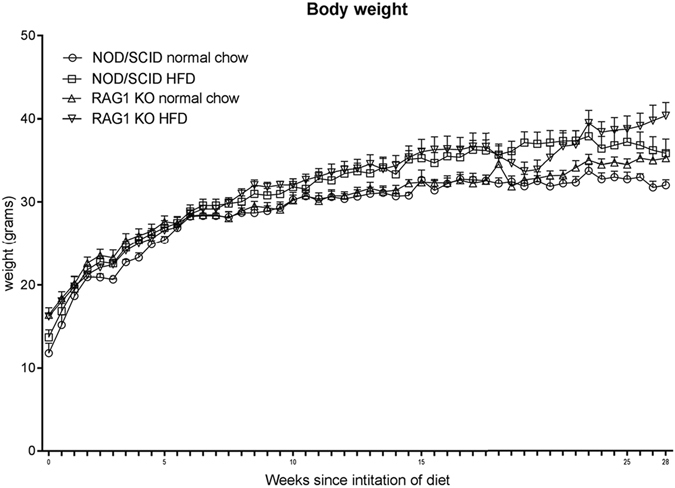

The effect of high-fat diet on body weight in NOD/SCID and Rag1−/− mice

Rag1 −/− and NOD/SCID mice were fed HFD (23% fat) or low-fat diet from 3 weeks of age and the effect on bodyweight determined. Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice had higher bodyweights than low-fat chow-fed Rag1 −/− mice from 2 weeks post weaning (Fig. 2). At endpoint, body weight was almost 20% higher in the HFD Rag1 −/− group, however, these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.0791) (Fig. 2). At endpoint, white adipose tissue was observed at the gross level during dissection in both HFD-fed mouse strains, however, brown adipose tissue (interscapular) was present in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice only.

Figure 2.

Mean body weight in NOD/SCID and Rag1 −/− mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) (23% fat, n = 8) compared to normal low-fat chow-fed control groups (n = 4). Mean + SEM.

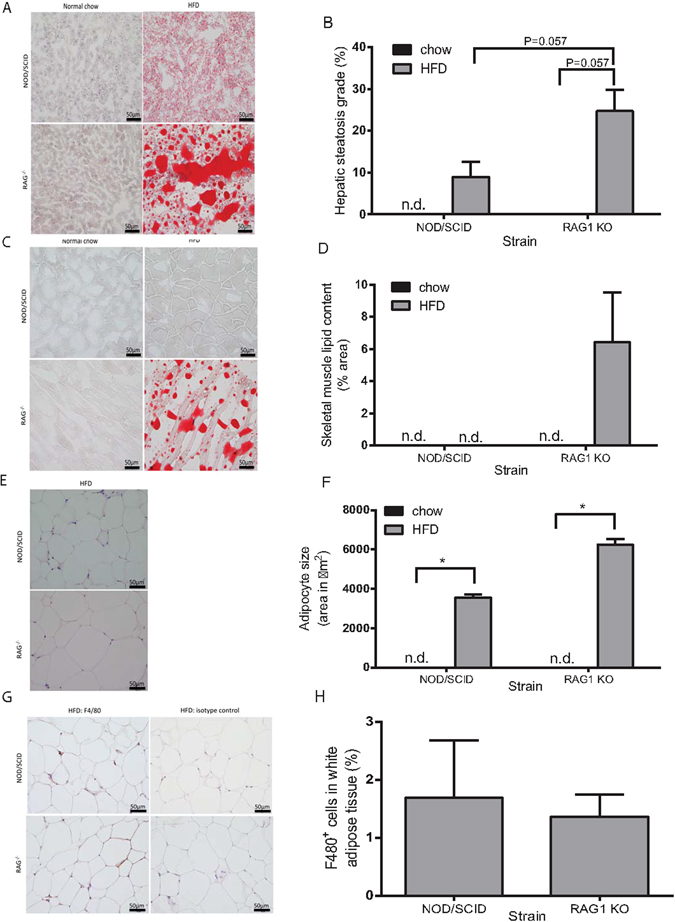

Histological analysis of adipose, skeletal muscle, hepatic and pancreatic tissue

Skeletal muscle and hepatic tissue were stained with oil-red-O (ORO) to determine the degree of lipid content (percent area). HFD-fed Rag1 −/− mice had greater hepatic lipid content (24.7 ± 10.1%, n = 4) than low-fat chow-fed Rag1 −/− mice (0.051 ± 0.089%, n = 3, P = 0.057) (Fig. 3A,B). Lipid was not detectable in the liver of low-fat chow-fed NOD/SCID mice. NOD/SCID HFD-fed mice exhibited lower hepatic lipid content (8.92 ± 7.41%, n = 4) compared to HFD-fed Rag1 −/−mice (24.7 ± 10.1%, n = 4, P = 0.057) (Fig. 3A,B). Intramyocellular lipids were present in Rag1 −/− mice fed HFD (6.42 ± 5.34%, n = 3), but not in low-fat chow-fed Rag1 −/− mice (n = 3, P = 0.10), nor in NOD/SCID mice on either diet (n = 3) (Fig. 3C,D).

Figure 3.

HFD increases lipid storage in Rag1 −/− and NOD/SCID mice with more pronounced effects in Rag1 −/− mice. (A) Oil-red-O stained liver histological sections demonstrate hepatic lipid in NOD/SCID and Rag1 −/− mice fed HFD for 28 weeks. Hepatic lipid is absent in mice fed low-fat chow. (B) Hepatic steatosis (% oil-red-O stained hepatic adipocyte area) in Rag1 −/− and NOD/SCID mice fed HFD. (C) Lipid accumulation in oil-red-O stained skeletal muscle in Rag1 −/− mice fed HFD, but not in Rag1 −/− normal chow-fed mice, or NOD/SCID mice. (D) Intramyocellular lipid content (% oil-red-O stained adipocyte area) in Rag1 −/− mice fed HFD. (E) White adipose tissue deposits (haematoxylin and eosin) in HFD-fed NOD/SCID and Rag1 −/− mice, are absent in mice fed low-fat chow. (F) Mean adipocyte size (expressed as area) is greater in Rag1 −/− mice fed HFD compared to NOD/SCID HFD-fed mice. (G) F4/80 positive (brown) immunostaining of white adipose tissue deposits demonstrates macrophage infiltration in white adipose tissue in NOD/SCID and Rag1 −/− mice fed HFD. (H) Percent of F4/80 positive stained cells in HFD-fed NOD/SCID and Rag1 −/− mice white adipose tissue. Mean + SEM. Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney test. *P ≤ 0.05. n.d. = not detectable. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Epididymal fat pad white adipose tissue was not visible in low-fat chow-fed NOD/SCID, or Rag1 −/− mice (n = 4) (Fig. 3E). Adipocytes were larger in HFD-fed Rag1 −/− mice (6252 ± 583 µm2, n = 4) compared to HFD-fed NOD/SCID mice (3549 ± 315 µm2, n = 3, P = 0.057). F4/80 immunohistochemistry revealed the presence of infiltrating macrophages in white adipose tissue deposits in both NOD/SCID and Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice (Fig. 3G,H).

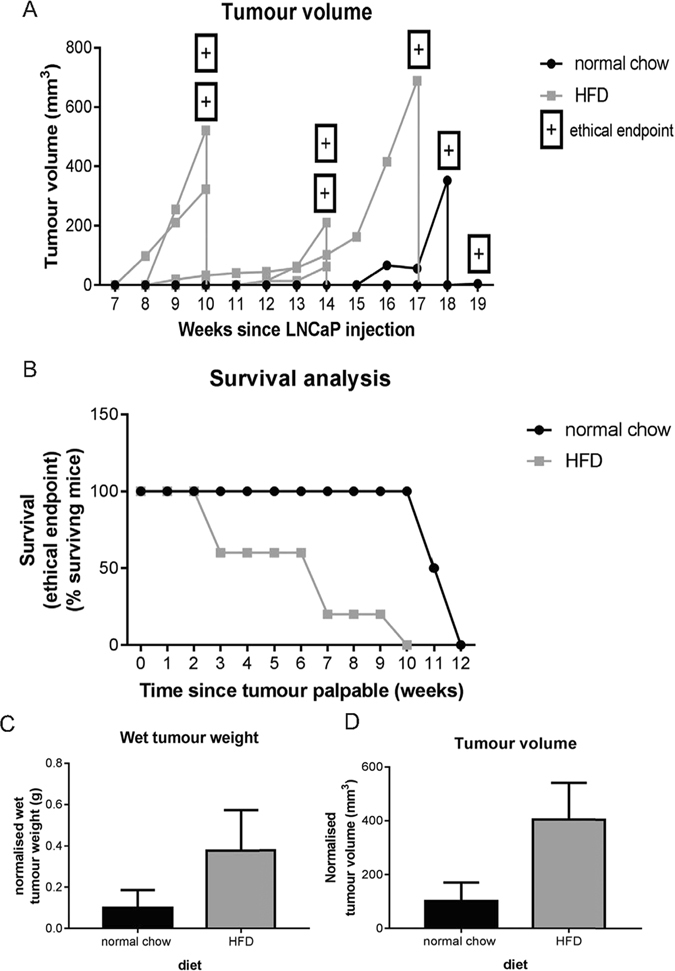

Growth of LNCaP subcutaneous xenografts is increased in hyperinsulinaemic, HFD-fed Rag1−/− mice

LNCaP xenograft tumours were palpable 8 weeks earlier in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice than low-fat chow-fed Rag1 −/− mice and tumours exhibited more rapid growth (Fig. 4A,C,D). Survival (to ethical endpoint) was significantly decreased in HFD-fed Rag1 −/− mice (54.55 ± 10.82% surviving mice, n = 5) compared to low-fat chow-fed mice (88.46 ± 8.31% surviving mice, n = 2, P = 0.034) (Fig. 4B). Metabolic parameters, including fasting blood insulin levels, insulin resistance, and steady-state β-cell function at endpoint, were also measured in Rag1 −/− mice fed HFD (see Supplementary Fig. S1), however, an increase in the group size is needed before statistically significant conclusions can be drawn.

Figure 4.

LNCaP subcutaneous xenografts grow more rapidly in HFD-fed Rag1 −/− mice. (A) HFD-fed Rag1 −/− mice (n = 5) develop larger and earlier tumours (shown as tumour volume) over time (weeks since subcutaneous xenograft implantation) compared to normal chow-fed mice (n = 2). P = NS. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. (B) Survival to ethical endpoint (from time of palpable tumour in weeks) is significantly shorter in mice fed HFD. Log-rank test. (C) Wet tumour weight (normalised to time since xenograft injection) at endpoint is greater in HFD mice. P = NS. Mann-Whitney test. (D) Tumour volume (normalised to time since xenograft injection) at endpoint is greater in HFD-fed mice P = NS. Mann-Whitney test. Mean + SEM.

Discussion

The present study is the first to investigate the long-term (28 week) metabolic effects of a Western, 23% high-fat diet (HFD) on two immunodeficient mouse strains suitable for human xenograft implantation. We demonstrate that the metabolic effects of 23% HFD (46% energy from fat) are more pronounced in Rag1 −/− compared to NOD/SCID mice, manifesting as higher fasting insulin levels, increased insulin resistance and steady-state β-cell function, lower insulin sensitivity, and increased adipose accumulation in skeletal muscle and liver tissue. The Rag1 −/− strain is, therefore, a suitable immunodeficient mouse model for investigating HFD-induced hyperinsulinaemia. Furthermore, our pilot LNCaP mouse xenograft study revealed that a moderate HFD promotes tumour growth. Compared to low-fat chow-fed Rag1 −/− mice, HFD-fed Rag1 −/− mice developed tumours earlier, and exhibited increased tumour growth over time and decreased survival to ethical endpoint.

Rag1 −/− mice in this study demonstrated impaired glucose tolerance within 16 weeks of HFD initiation. We surmise that this is likely to be a reflection of their predominantly C57BL/6 J genetic background (N6). It is well established that the C57BL/6 J strain is genetically predisposed to developing metabolic syndrome when fed a HFD18, 33. Previous studies, in which Rag1 −/− and C57Bl/6 J mice were fed a Western diet (42.2% calories from milk fat and 42.8% calories from carbohydrate) for 11 weeks, demonstrated that these strains develop impaired glucose tolerance compared to low-fat diet fed mice, and no significant difference was observed between Rag1 −/− and C57BL/6 J HFD-fed mice21. The Rag1 −/− mouse bred onto a C57BL/6 J genetic background is, therefore, a useful model for studying the effects of insulin resistance, hyperinsulinaemia and, potentially, other components of the metabolic syndrome on cancer development and progression.

NOD/SCID and NSG mice are commonly used for xenograft studies due to their high tumour engraftment rate34, however, they are relatively resistant to diet-induced hyperinsulinaemia22 as they lack fully competent immune systems. Rag1 −/− mice mice (on a BALB/c background) have been used for cancer allograft and xenograft studies for prostate cancer35. Similarly, Rag2 −/− mice, which lack mature B and T lymphocytes, due to a mutation in the recombination-activating gene encoding the RAG2 protein36, have been employed to study endometrial cancer37 and oral squamous cell carcinoma38. Classically, Rag1 −/− mice may not be considered as amenable to xenograft studies, as they retain some innate immune function, including moderate natural killer cell (NK) activity, which reduces engraftment rate and may distort the architecture of engrafted tumours39. However, as the development of insulin resistance is an inflammatory process2, the presence of some innate immunity may be advantageous for the study of HFD and cancer. Indeed, we reveal that engraftment of human prostate cancer cell line xenografts is possible in both HFD and chow-fed Rag1 −/− mice, with tumours developing to a palpable size more rapidly in HFD-fed mice.

Impaired glucose and insulin tolerance have been reported to develop in Rag1 −/− mice as early as 1 week after initiation of a 60% HFD20, however, this high-fat content is not representative of a human diet. The diet used in our study is closer to a Western human diet, with 46% energy from fat, (14.31% of which is saturated fat), 34% carbohydrate and 20% protein. A study by Liu and colleagues21 employed a comparable diet, with similar energy from fat (42.2% energy) but a higher carbohydrate (42.8%) and lower protein content (15%) than the diet used in our study. Studies where mice were fed 60% or 46% HFD20, 21 revealed similar diet-induced metabolic changes, including significantly impaired glucose tolerance in HFD-fed mice compared to chow-fed controls after 10–16 weeks on the diet21. Our study investigated chronic effects (28 weeks) of a high-fat diet, permitting the assessment of pancreatic β-cell function over time and demonstrating that increased β-cell activity compensates for hyperglycaemia, allowing a progression to hyperinsulinaemia. Our study is novel, as it compares the metabolic effects of HFD on two commonly-used xenograft hosts, Rag1 −/− and NOD/SCID mice. Both strains lack a competent adaptive immune system, however, only the NOD/SCID mice lack competent innate immunity22, 23.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of a Western HFD in Rag1 −/− mice. In these mice, fasting blood glucose measurements at 28 weeks, and glucose tolerance at 23 weeks, improved compared to 16 weeks; possibly as a result of β-cell compensation and a significant increase in blood insulin levels. HOMA revealed significantly greater insulin resistance and steady-state β-cell function, and lower insulin sensitivity compared to low-fat chow-fed mice. This is likely to reflect the diabetogenic C57BL/6 J genetic background of Rag1 −/− mice. Similarly, glucose tolerance improves with age in C57BL/6 J mice fed a normal chow diet as a result of age-related increases in islet size and pancreatic insulin content40. Our pilot LNCaP xenograft study (conducted in mice backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice for 10 generations) demonstrates that Rag1 −/− mice fed a Western HFD display changes in metabolic parameters, however, greater sample size is needed to determine if these changes are statistically significant.

Although glucose tolerance in HFD-fed Rag1 −/− mice improved with time, glucose tolerance in NOD/SCID mice became progressively impaired. NOD/SCID HFD-fed mice also developed symptoms of metabolic disturbance, including increased plasma insulin, insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, and increased adipocyte size, however, these changes were more pronounced in HFD-fed Rag1 −/− mice. Although present in Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice, intramyocellular lipid was not observed in NOD/SCID mice. Previous studies on the effect of 46% or 60% HFD in Rag1 −/− mice investigated adipose tissue accumulation in subcutaneous, epididymal, mesenteric and perirenal depots, but lipid accumulation within metabolic organs crucial for energy homeostasis, such as the liver and skeletal musculature, were not measured20, 21. Increased hepatic steatosis and skeletal muscle lipid accumulation measured in HFD-fed Rag1 −/− mice in our study is, thus, a novel finding.

Interestingly, Rag1 −/− HFD mice were the only group observed to retain interscapular brown adipose tissue at endpoint. Brown adipose tissue has a high thermogenic capacity and plays a role in body weight control41, 42. This observation may suggest that Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice adapt to a high-fat diet, partly through increased brown adipose tissue mass and minimised weight gain, to maintain energy homeostasis. As the animal facility was maintained at 20–23 °C, and the murine thermoneutral range is 30–33 °C43, fat stores may have been depleted in low-fat chow-fed animals in an attempt to maintain body temperature44.

The immune system and inflammation have an integral role in the pathogenesis of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and metabolic syndrome19, and the majority of metabolic studies have employed immunocompetent mice12. In this study we demonstrate that white adipose tissue was infiltrated with F4/80 positive macrophages in both NOD/SCID and Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice, while animals fed normal chow lacked visible adipose deposits. The infiltration of adipose tissue by macrophages in obesity is thought to play a critical role in mediating insulin resistance and the development of T2DM, triggering β-cell apoptosis and reducing the secretion of insulin2, 45. Our observation correlates with previous studies demonstrating significantly increased activated macrophage-related cytokine IL-1246 in the circulation of Rag1 −/− HFD-fed mice compared to Rag1 −/− fed a low-fat diet (16.7% energy from fat)21.

Our study demonstrates that a Western 23% HFD increases fat mass, reduces insulin tolerance, increases LNCaP human prostate cancer xenograft growth, and decreases survival to ethical endpoints in male Rag1 −/− mice. Further studies are required, however, to determine if the Rag1 −/− mouse is a useful model for investigating the interaction between HFD consumption and female cancers, particularly given the growing body of evidence describing gender-specific responses to HFD in C57BL/6 mice47. Specifically, male mice fed a HFD develop hyperinsulinaemia and low-grade systemic inflammation, whereas females do not47 - possibly due to the anti-inflammatory effects of oestrogen and expansion of regulatory T cells in female mice fed a HFD48, 49. Given the strong link between the development of endometrial and breast cancers and metabolic syndrome10, 50, the Rag1 −/− model is likely to be useful for the further investigation of this association.

In conclusion, this is the first study to show that Rag1 −/− mice fed a Western 23% HFD from weaning develop a number of symptoms associated with metabolic dysfunction, including hyperinsulinaemia, increased fasting insulin levels, insulin resistance, decreased insulin sensitivity, increased adiposity, hepatic steatosis and intramyocellular lipid accumulation. NOD/SCID mice fed the same diet developed some metabolic sequelae, however, these effects were more pronounced in Rag1 −/− mice. Although further studies are required, this study demonstrates that a Western 23% HFD in Rag1 −/− mice increases the growth rate of prostate cancer xenografts and significantly decreases survival to ethical endpoint compared to low-fat chow-fed mice. The Rag1 −/− immunodeficient mouse is a promising mouse model for exploring the interaction between metabolic disturbances and the development and progression of cancers associated with symptoms of metabolic syndrome.

Methods

Hyperinsulinaemic mouse model and pilot xenograft study

To establish hyperinsulinaemia in immunocompromised mice, male 3-week-old NOD.CB17-Prkdc scid/Arc (NOD/SCID) and recombination-activation gene deficient mice (B6.SVJ129-Rag1 tm1Bal/Arc; Rag1 −/−) (Jackson Laboratories; supplied by Animal Resource Centre, Murdoch, WA, Australia) were weaned onto an ad libitum diet of low-fat, normal chow (4.8% fat, 20% protein, 75.2% carbohydrate, 12152, Specialty Feeds, Glen Forrest, WA, Australia, http://www.specialtyfeeds.com), or Western, high-fat diet (23% fat, 46% digestible energy from fat, 20% energy from protein, 34% energy from carbohydrate, SF04–027, Specialty Feeds) (n = 4–8 per mouse strain and diet). Rag1 −/− mice were backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 J background for six generations (N6; Animal Resources Centre). Mice were maintained on this diet for 28 weeks in total, with bodyweight monitored twice weekly. LNCaP human prostate cancer cell line xenograft studies were performed using Rag1 −/− mice backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 J background for ten generations (N10; Animal Resources Centre). Mice were initiated on HFD, or low-fat normal chow at weaning (4 weeks of age), and injected with 2 × 106 LNCaP cells in Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS) (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) at a 1:1 ratio with growth factor reduced Matrigel (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in the subcutaneous tissue of the right flank at 6 weeks of age. Mice were maintained on HFD or low-fat normal chow, and body weight and tumour volume monitored weekly using calipers. For mice with LNCaP xenografts, experimental endpoint was determined by tumour volume (>1000 mm3), calculated using the equation ‘tumour volume = length × width2/2’, or if an ethical endpoint was reached (based on a combination of signs of stress including increased heart rate, inactivity, reduced interaction with cage mates, abnormal posture and/or >20% body weight loss as per ethical approval and the Australian Code). Xenograft volume was normalised for different durations to ethical endpoint after implantation using the equation ‘(xenograft volume/time since implantation) × 100’. Metabolic parameters (see Supplementary Fig. 1) were normalised for time since weaning using the equation ‘(original measurement/time) × 100’. Mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions in individually-ventilated cages, at a room temperature of 20–23 °C, with a 12 hour light-dark cycle. All methods were conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and regulations. Animal ethics approval was granted from the University of Queensland and Queensland University of Technology animal ethics committees, and human ethics approval for cell line (LNCaP) use was granted from Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test

At 16 and 23 weeks after initiation of the diet, intraperitoneal (i.p.) glucose tolerance tests were performed (n = 4 mice per group) to determine effect of diet on glucose tolerance. Mice were fasted for 16 hours and baseline glucose levels measured in tail-tip blood with a One-touch Ultra blood glucose monitoring system and test strips (Accu-Chek Performa, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Glucose (20% solution, 2 g/kg) was injected i.p. and blood glucose levels assessed at 15, 30, 60 and 120 minutes post injection. Fasting blood glucose was measured at the endpoint of the experiment (28 weeks post weaning). Surrogate indices of insulin resistance, insulin sensitivity and steady-state β-cell function were determined using the homeostatic model for assessment calculator (HOMA2)51, available from the Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism31, using measured fasting glucose and insulin levels. HOMA analysis is an accepted surrogate for measuring insulin resistance in rodents52.

Blood and tissue sample preparation

Blood for biochemical measurements was collected by terminal endpoint cardiac puncture. Tissues of interest (brown fat, epididymal fat pad, liver and skeletal muscle) were excised, frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. embedding compound (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA), and stored at −80 °C or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological and immunohistochemical analysis.

Hormone measurement

Fasting serum insulin was determined by ELISA (EMD Merck Millipore Group, Darmstadt, Germany). A multiplex ELISA (metabolic panel Milliplex kit, EMD Merck Millipore Group) was used to determine fasting serum insulin, glucagon, leptin and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in mice with LNCaP xenografts. Absorbance at 450 nm and 595 nm was determined using a FLUOstar Omega plate reader and software (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany), with absorbance values interpolated using linear regression.

Histological tissue analysis

Cryosections (6–10 μm thick, Leica CM1850 cryotome) were collected onto warm, charged Menzel Superfrost slides (Thermo Fisher), air dried for 1–2 hours and stored at −80 °C. Sections were fixed with ice-cold 100% acetone for 10 mins, followed by air-drying. White adipose tissue was processed and embedded in paraffin before sectioning (5 µM sections). One section from each specimen was stained with Mayer's haematoxylin and eosin (Sigma-Aldrich), and neutral lipids were stained in skeletal muscle and liver sections using oil-red-O stain (ORO; Sigma-Aldrich). Frozen sections were fixed in formalin, rinsed in 60% isopropanol, stained with ORO for 15 minutes, rinsed in 60% isopropanol, and mounted with coverslips using CC/Mount (Sigma-Aldrich). Stained sections were observed using an Olympus BX41/702 microscope (U-CMAD3) and the area of red, ORO-stained lipid (minimum n = 3 samples per group and n = 3 fields per section) quantified using the thresholding function in the ImageJ software (Research Services Branch, National Institute of Health, Washington, Maryland, USA)53. Adipocyte size (mean area of white adipose cells, minimum n = 3 samples per group and n = 3 fields per section) was quantified using the freehand area selection tool in ImageJ.

Immunohistochemistry was performed to investigate the expression of the inflammatory macrophage marker F4/80. After rehydration in a series of xylene and ethanol washes, and antigen retrieval (Carezyme Trypsin, Biocare Medical), tissue sections were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidases. Sections were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) and a blocking step using 10% BSA in PBST. Rat anti-mouse F4/80 primary antibody (122602 Cell Signalling Technology, Massachusetts, USA) was diluted 1:50 in PBST with 10% BSA. Tissue sections were washed in PBST, incubated with HRP-polymer conjugates (SuperPicture, Thermo Fisher), and incubated with the chromagen diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), as per manufacturer's specifications. Slides were counterstained with Mayer's haematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted with coverslips using D.P.X neutral mounting medium (Sigma-Aldrich). The number of F4/80 positive cells was quantified as a percent of the total number of cells in the field (n = 3 samples per group and n = 3 fields per section) using ImageJ software53.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v6.01 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Non-normally distributed data was analysed using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests. Normally distributed data was analysed using parametric two-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparison tests with P ≤ 0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grant (to L.K.C., I.S., A.C.H., C.C.), a QUT Vice-Chancellor's Senior Research Fellowship (to I.S.), the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing and the Movember Foundation and the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia through a Movember Revolutionary Team Award (MRTA) (to L.K.C., A.C.H., C.C.N.).

Author Contributions

Study design: M.L.M., I.S., P.L.J., L.K.C. Laboratory work and data analysis: M.L.M., P.L.J., P.B.T., G.J.C., L.K.P., L.K.C. and E.T.S. Drafting of manuscript: M.L.M., I.S., P.L.J., L.K.C. Editing and final approval of the manuscript: M.L.M., I.S., P.L.J., L.K.C., P.B.T., G.J.C., L.K.P., E.T.S., C.C., L.S.G., A.C.H. and C.C.N.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Penny L. Jeffery and Lisa K. Chopin contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00443-x

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Penny L. Jeffery, Email: p.jeffery@qut.edu.au

Lisa K. Chopin, Email: l.chopin@qut.edu.au

References

- 1.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu H, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1821–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI200319451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lumeng CN, Saltiel AR. Inflammatory links between obesity and metabolic disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:2111–2117. doi: 10.1172/JCI57132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finucane OM, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor deficiency ameliorates high-fat diet induced insulin resistance in mice with reduced adipose inflammation and hepatic steatosis. PLoS One. 2014;9:113369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park J, Euhus DM, Scherer PE. Paracrine and endocrine effects of adipose tissue on cancer development and progression. Endocr. Rev. 2011;32:550–570. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowey S, Hardy RW. The metabolic syndrome: A high-risk state for cancer? Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:1505–1522. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma J, et al. Prediagnostic body-mass index, plasma C-peptide concentration, and prostate cancer-specific mortality in men with prostate cancer: a long-term survival analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1039–1047. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70235-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maiti B, Kundranda MN, Spiro TP, Daw HA. The association of metabolic syndrome with triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;121:479–483. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0591-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esposito K, et al. Metabolic syndrome and endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2014;45:28–36. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-9973-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colangelo LA, Gapstur SM, Gann PH, Dyer AR, Liu K. Colorectal cancer mortality and factors related to the insulin resistance syndrome. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy AJ, Ellacott KL, King VL, Hasty AH. Mouse models of the metabolic syndrome. Dis. Model. Mech. 2010;3:156–166. doi: 10.1242/dmm.003467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingalls AM, Dickie MM, Snell GD. Obese, a new mutation in the house mouse. J. Hered. 1950;41:317–318. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a106073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hummel KP, Dickie MM, Coleman DL. Diabetes, a new mutation in the mouse. Science. 1966;153:1127–1128. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3740.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickie MM. Mutations at the agouti locus in the mouse. J. Hered. 1969;60:20–25. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a107920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buettner R, et al. Defining high-fat-diet rat models: metabolic and molecular effects of different fat types. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006;36:485–501. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woods SC, Seeley RJ, Rushing PA, D’Alessio D, Tso P. A controlled high-fat diet induces an obese syndrome in rats. J. Nutr. 2003;133:1081–1087. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.4.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Surwit RS, Kuhn CM, Cochrane C, McCubbin JA, Feinglos MN. Diet-induced type II diabetes in C57BL/6J mice. Diabetes. 1988;37:1163–1167. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.9.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YS, et al. Inflammation is necessary for long-term but not short-term high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2011;60:2474–2483. doi: 10.2337/db11-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, et al. Lack of mature lymphocytes results in obese but metabolically healthy mice when fed a high-fat diet. Int. J. Obes. 2015;39:1548–1557. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedline RH, et al. Genetic ablation of lymphocytes and cytokine signaling in nonobese diabetic mice prevents diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. FASEB J. 2016;30:1328–1338. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-280610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamauchi T, et al. Polymorphic Sirpa is the genetic determinant for NOD-based mouse lines to achieve efficient human cell engraftment. Blood. 2013;121:1316–1325. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-440354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosma GC, Custer RP, Bosma MJ. A severe combined immunodeficiency mutation in the mouse. Nature. 1983;301:527–530. doi: 10.1038/301527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee RH, et al. Multipotent stromal cells from human marrow home to and promote repair of pancreatic islets and renal glomeruli in diabetic NOD/scid mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:17438–17443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608249103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu KK, Huan Y. Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Models in Mice and Rats. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2001;40:5.47:5.47.1–5.47.14. doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph0547s40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duffaut C, Galitzky J, Lafontan M, Bouloumie A. Unexpected trafficking of immune cells within the adipose tissue during the onset of obesity. Biochem Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;384:482–485. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mombaerts P. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;68:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ito R, Takahashi T, Katano I, Ito M. Current advances in humanized mouse models. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2012;9:208–214. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Behan JW, et al. Activation of adipose tissue macrophages in obese mice does not require lymphocytes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:1380–1388. doi: 10.1002/oby.20159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diabetes Trial Unit, The Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism. HOMA Calculator. University of Oxfordhttps://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/homacalculator/index.php.

- 32.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1487–1495. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toye AA, et al. A genetic and physiological study of impaired glucose homeostasis control in C57BL/6J mice. Diabetologia. 2005;48:675–686. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1680-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hudson WA, Li Q, Le C, Kersey JH. Xenotransplantation of human lymphoid malignancies is optimized in mice with multiple immunologic defects. Leukemia. 1998;12:2029–2033. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Q, et al. Blockade of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in tumor-reactive CD8(+) T cells activates the antitumor immune response cycle. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1733–1743. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shinkai Y, et al. RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell. 1992;68:855–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenberg LH, Slayden OD. Human endometriotic xenografts in immunodeficient RAG-2/gamma(c)KO mice. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;190:1788–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reuther T, et al. The RAG 2 mouse model for xenografted human oral squamous cell carcinoma. Contemp. Top. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2002;41:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maykel J, et al. NOD-scidIl2rg (tm1Wjl) and NOD-Rag1 (null) Il2rg (tm1Wjl): a model for stromal cell-tumor cell interaction for human colon cancer. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2014;59:1169–1179. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3168-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leiter EH, Premdas F, Harrison DE, Lipson LG. Aging and glucose homeostasis in C57BL/6J male mice. FASEB J. 1988;2:2807–2811. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.12.3044905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harms M, Seale P. Brown and beige fat: development, function and therapeutic potential. Nat. Med. 2013;19:1252–1263. doi: 10.1038/nm.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ. A role for brown adipose tissue in diet-induced thermogenesis. Nature. 1979;281:31–35. doi: 10.1038/281031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herrington LP. The heat regulation of small laboratory animals at various environmental temperatures. Am. Heart J. 1940;19:628. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maloney SK, Fuller A, Mitchell D, Gordon C, Overton JM. Translating animal model research: Does it matter that our rodents are cold? Physiology. 2014;29:413–420. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00029.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ehses JA, Boni-Schnetzler M, Faulenbach M, Donath MY. Macrophages, cytokines and beta-cell death in Type 2 diabetes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36:340–342. doi: 10.1042/BST0360340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heufler C, et al. Interleukin-12 is produced by dendritic cells and mediates T helper 1 development as well as interferon-gamma production by T helper 1 cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996;26:659–668. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pettersson US, Walden TB, Carlsson PO, Jansson L, Phillipson M. Female mice are protected against high-fat diet induced metabolic syndrome and increase the Regulatory T Cell population in adipose tissue. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Djouadi F, et al. A gender-related defect in lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis in peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor alpha- deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:1083–1091. doi: 10.1172/JCI3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macotela Y, Boucher J, Tran TT, Kahn CR. Sex and depot differences in adipocyte insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism. Diabetes. 2009;58:803–812. doi: 10.2337/db08-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gezgen G, Roach EC, Kizilarslanoglu MC, Petekkaya I, Altundag K. Metabolic syndrome and breast cancer: an overview. J. BUON. 2012;17:223–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levy JC, Matthews DR, Hermans MP. Correct homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) evaluation uses the computer program. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:2191–2192. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.12.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Antunes LC, et al. Validation of HOMA-IR in a model of insulin-resistance induced by a high-fat diet in Wistar rats. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2016;60:138–142. doi: 10.1590/2359-3997000000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hartig SM. Basic image analysis and manipulation in ImageJ. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2013;102:14.15:14.15.1–14.15.12. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1415s102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.