Abstract

BACKGROUND

Increasing overuse of opioids in the United States may be driven in part by physician prescribing. However, the extent to which individual physicians vary in opioid prescribing and the implications of that variation for long-term opioid use and adverse outcomes in patients are unknown.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis involving Medicare beneficiaries who had an index emergency department visit in the period from 2008 through 2011 and had not received prescriptions for opioids within 6 months before that visit. After identifying the emergency physicians within a hospital who cared for the patients, we categorized the physicians as being high-intensity or low-intensity opioid prescribers according to relative quartiles of prescribing rates within the same hospital. We compared rates of long-term opioid use, defined as 6 months of days supplied, in the 12 months after a visit to the emergency department among patients treated by high-intensity or low-intensity prescribers, with adjustment for patient characteristics.

RESULTS

Our sample consisted of 215,678 patients who received treatment from low-intensity prescribers and 161,951 patients who received treatment from high-intensity prescribers. Patient characteristics, including diagnoses in the emergency department, were similar in the two treatment groups. Within individual hospitals, rates of opioid prescribing varied widely between low-intensity and high-intensity prescribers (7.3% vs. 24.1%). Long-term opioid use was significantly higher among patients treated by high-intensity prescribers than among patients treated by low-intensity prescribers (adjusted odds ratio, 1.30; 95% confidence interval, 1.23 to 1.37; P<0.001); these findings were consistent across multiple sensitivity analyses.

CONCLUSIONS

Wide variation in rates of opioid prescribing existed among physicians practicing within the same emergency department, and rates of long-term opioid use were increased among patients who had not previously received opioids and received treatment from high-intensity opioid prescribers. (Funded by the National Institutes of Health.)

Rates of opioid prescribing and opioid-related overdose deaths have quadrupled in the United States over the past three decades.1–3 This epidemic has increasingly affected the elderly Medicare population, among whom rates of hospitalization for opioid overdoses quintupled from 1993 through 2012.4–6 The risks of opioid use are particularly pronounced among the elderly, who are vulnerable to their sedating side effects, even at therapeutic doses.7 Multiple studies have shown increased rates of falls, fractures, and death from any cause associated with opioid use in this population.8–11 Even short-term opioid use may confer a predisposition to these side effects and to opioid dependence.12

It is frequently argued that the prescribing behavior of physicians has been a driver of the opioid epidemic.13,14 Prescribing has increased to the point that in 2010, enough opioids were prescribed in the United States to provide every American adult with 5 mg of hydrocodone every 4 hours for a month.1,14 This growth may be driven in part by high variability in physician prescribing of opioids; this variability may reflect overprescribing beyond what is required for appropriate pain management.1,15,16 This inconsistency is not surprising, because few clinical guidelines exist, and there is limited evidence to direct the appropriate use of opioids.17,18 However, few studies have investigated the extent to which individual physicians vary in opioid prescribing and the implications of that variation for long-term opioid use and related adverse outcomes in patients.

To examine the extent to which emergency physicians within the same hospital varied in rates of opioid prescribing, we studied a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries who received treatment in an emergency department and who had not used prescription opioids within 6 months before the index visit to the emergency department. In order to understand how initial exposure to an opioid relates to subsequent outcomes, we identified high-intensity and low-intensity opioid prescribers within each hospital and examined rates of long-term opioid use and future hospitalizations among patients treated by these two groups of prescribers.19,20 To address the challenge of selection bias, we relied on the fact that patients are unlikely to choose an emergency department physician once they have chosen a facility.

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION

Using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services carrier files for a 20% random sample of beneficiaries from January 1, 2008, through December 31, 2011, we identified index emergency department visits at acute care hospitals by Medicare beneficiaries. We defined an index visit as the earliest visit at which a beneficiary had an evaluation and a management claim by an emergency medicine physician with a place-of-service designation in the emergency department. Emergency medicine physicians were defined as physicians with an emergency medicine specialty who billed 90% or more of claims with an emergency department place of service. We included only one index visit to the emergency department per beneficiary and excluded all visits to the emergency department that resulted in a hospital admission.

We limited our analyses to beneficiaries who had been continuously enrolled in Medicare Part D for 18 months or more, including at least the period from 6 months before the index visit to 12 months afterward. We included only beneficiaries who had not had an opioid prescription filled in the 6 months before the index visit. In addition, we excluded beneficiaries with hospice claims or a cancer diagnosis between 2008 and 2012.

We assigned each index emergency department visit to a physician according to the billing National Provider Identifier (NPI) and then linked each visit to a hospital by matching to facility claims in the outpatient department file according to the date and beneficiary. To ensure that we had an adequate sample size at the physician and hospital level, we excluded physicians with fewer than five emergency department visits and hospitals with fewer than five physicians billing for emergency department visits in our sample. If physicians practiced in more than one hospital, they were assigned to the hospital at which they had the most visits, and any visits at other facilities were excluded.

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Harvard Medical School, which waived the requirement for informed consent since the data were deidentified and only aggregate results would be reported.

DEFINITIONS OF OPIOID PRESCRIPTIONS AND INTENSITY OF PHYSICIANS’ PRESCRIBING

We identified prescription claims corresponding to an opioid (excluding methadone) according to the National Drug Code in the Medicare Part D database.16 We attributed an opioid prescription to an index emergency department visit and the associated physician if it was filled by the patient within 7 days after the date of the emergency department visit; in a sensitivity analysis, we restricted this duration to 3 days. This attribution method was necessary because prescriber NPI information is not available in the Part D database (see the Methods and Results section in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org). For this and subsequent opioid prescriptions, we extracted the number of days for which opiates were supplied and calculated the morphine equivalents dispensed, using standard conversion tables.21

We defined the main exposure as treatment by a “high-intensity” or “low-intensity” opioid prescribing physician within the same hospital. For each physician, we first calculated the proportion of all emergency department visits after which an opioid prescription was filled. We then grouped physicians into quartiles of rates of opioid prescribing within each hospital and classified physicians as being in the top (high-intensity) or bottom (low-intensity) quartile of prescribing rates. In 93 hospitals, because of a high number of prescribers who did not prescribe opioids, there were fewer than four separate groups of prescribers to assign to quartiles; therefore, the highest and lowest prescribers in a hospital were assigned to the high-intensity and low-intensity groups. We also defined an alternative exposure, classifying physicians according to the median dose (in morphine equivalents) of prescriptions filled after an emergency department visit (“high-dose intensity” and “low-dose intensity”).

OUTCOMES

Our primary outcome was long-term opioid use, which we defined as 180 days or more of opioids supplied in the 12 months after an index emergency department visit, excluding prescriptions within 30 days after the index visit. We applied this exclusion because otherwise this outcome, by design, would be correlated with our definition of the main exposure. We chose 180 days as a specific marker for clinically significant long-term opioid use beyond the common duration of 90 days described in previous literature.16,22,23 Therefore, this outcome captures the extent to which other physicians prescribe opioids for the subsequent 12 months after a patient’s index emergency department visit.

Secondary outcomes were rates of hospital encounters (emergency department visits, hospitalizations, or both), including those potentially related to adverse effects of opioids and those associated with a selection of medical conditions that were unlikely to be influenced by opioid use, in the 12 months after an index emergency department visit (definitions are provided in the Methods and Results section in the Supplementary Appendix).8–10,24 To assess for possible undertreatment of pain by low-intensity prescribers that could have led to repeat emergency care, we also measured rates of repeat emergency department visits at 14 and 30 days that resulted in the same primary diagnosis as the initial emergency department visit, classified according to Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) groups (categorizations of codes in the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision).25

PATIENT COVARIATES

We collected information on the patients’ age, sex, race or ethnic group, dual eligibility for Medicaid and Medicare coverage, and disability status.26 Using the Chronic Conditions Warehouse database, we also captured the presence of any of 11 chronic conditions (Table 1) as well as the number of coexisting chronic conditions that a patient had at the time of an index emergency department visit.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Patients, According to Opioid Prescribing Intensity of Physician Seen.*

| Characteristic | Patients Treated by Low-Intensity Prescriber (N = 215,678)† | Patients Treated by High-Intensity Prescriber (N = 161,951)† | P Value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 68.8±16.3 | 68.2±16.4 | <0.001 |

| Female sex (%) | 64.5 | 64.5 | 0.75 |

| White race (%)§ | 76.6 | 75.9 | 0.03 |

| Medicare–Medicaid dual eligibility (%) | 49.3 | 49.6 | 0.19 |

| Disabled (%) | 36.4 | 37.6 | <0.001 |

| Chronic conditions (no.) | 3.6±2.3 | 3.5±2.3 | <0.001 |

| Presence of chronic illness (%) | |||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 49.8 | 48.5 | <0.001 |

| Alzheimer’s dementia | 17.5 | 16.0 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 13.6 | 12.7 | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 17.3 | 16.3 | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 20.6 | 20.1 | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 28.1 | 27.2 | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 30.5 | 29.0 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 39.5 | 39.5 | 0.94 |

| Diabetes | 37.8 | 37.7 | 0.69 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 69.5 | 69.1 | 0.09 |

| Hypertension | 78.1 | 77.4 | <0.001 |

| Census region (%) | |||

| Northeast | 19.8 | 20.9 | 0.03 |

| Midwest | 24.4 | 23.2 | 0.01 |

| South | 38.4 | 38.6 | 0.82 |

| West | 17.3 | 17.3 | 0.97 |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD.

Within each hospital, high-intensity and low-intensity prescribers were defined as the top (high) or bottom (low) quartile of emergency physician prescribers in terms of opioid prescribing. Since many physicians did not prescribe opioids, some hospitals had many physicians with prescribing rates equal to zero in the low-intensity prescriber group, making it larger overall than the high-intensity group. Low-intensity prescribers included 8297 physicians; the total number (±SD) of patients per physician was 26.0±18.6. High-intensity prescribers included 6133 physicians; the total number of patients per physician was 26.4±18.5.

Unadjusted P values were estimated with the use of Student’s t-test for means or the z-test for comparison of proportions.

Race or ethnic group was self-reported.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Our strategy to reduce selection bias relied on the assumption that within the same hospital, patients do not choose specific emergency physicians, and therefore patients treated by physicians of varying opioid prescribing intensity may be similar with respect to both observable and unobservable characteristics. To assess this approach, we compared the characteristics of patients who saw high-intensity prescribers with those who saw low-intensity prescribers. We assessed balance in the case mix by comparing rates of visits classified according to the top 25 CCS groups, as well as by plotting the cumulative distribution of the primary-diagnosis CCS group between high-intensity and low-intensity prescribers. Differences in distributions between groups were assessed with the use of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.27

We then computed unadjusted rates and odds ratios for each outcome, stratified according to treatment by a high-intensity or low-intensity opioid prescriber. To account for residual differences between patient populations, we estimated adjusted odds ratios with patient-level multivariable logistic regression. Dependent variables were the occurrence of primary or secondary outcomes. The key explanatory variable was a binary indicator for whether a patient was treated by a high-intensity or low-intensity prescriber (the middle two quartiles of prescribers were not included in these models). Other covariates included the patients’ age, sex, race or ethnic group, Medicaid eligibility, and disability status, as well as the presence of 11 different chronic conditions. We prespecified several subgroup analyses to assess for heterogeneity (Table 2). All models accounted for grouping of patients within hospitals with the use of robust standard errors clustered at the hospital level.28

Table 2.

Rate of Filling a Prescription for Opioids within 7 Days after Emergency Department Visit and Rate of Long-Term Use, According to Opioid Prescribing Intensity of Physician Seen.*

| Variable | Initial Rate of Opioid Prescription in Emergency Department | Rate of Long-Term Use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Rate | Low-Intensity Prescriber | High-Intensity Prescriber | Low-Intensity Prescriber | High-Intensity Prescriber | |

| percent | |||||

| Overall rate of opioid prescribing | 14.7 | 7.3 | 24.1 | 1.16 | 1.51 |

|

| |||||

| Rate of prescribing according to patient characteristic | |||||

|

| |||||

| Age | |||||

| <65 yr | 17.9 | 8.8 | 28.9 | 2.09 | 2.82 |

| 65–74 yr | 16.4 | 8.4 | 26.4 | 0.86 | 1.00 |

| 75–84 yr | 12.3 | 6.0 | 20.4 | 0.68 | 0.89 |

| ≥85 yr | 8.9 | 4.3 | 15.6 | 0.86 | 1.01 |

|

| |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 15.1 | 7.6 | 24.7 | 1.22 | 1.53 |

| Female | 14.4 | 7.1 | 23.8 | 1.13 | 1.51 |

|

| |||||

| Race | |||||

| White | 14.6 | 7.5 | 23.7 | 1.16 | 1.50 |

| Black | 14.9 | 6.8 | 25.0 | 1.38 | 1.87 |

|

| |||||

| Medicare–Medicaid dual eligibility | |||||

| No | 14.4 | 7.4 | 23.4 | 0.71 | 0.87 |

| Yes | 15.0 | 7.2 | 24.8 | 1.62 | 2.17 |

|

| |||||

| No. of chronic conditions† | |||||

| 0 | 18.7 | 9.5 | 29.9 | 1.29 | 1.73 |

| 1 or 2 | 16.9 | 8.5 | 27.4 | 1.07 | 1.52 |

| ≥3 | 13.3 | 6.5 | 22.0 | 1.17 | 1.48 |

|

| |||||

| Alzheimer’s disease | |||||

| No | 15.9 | 8.0 | 25.9 | 1.15 | 1.52 |

| Yes | 8.5 | 4.0 | 14.7 | 1.19 | 1.49 |

|

| |||||

| Disabled | |||||

| No | 13.4 | 6.7 | 22.1 | 0.71 | 0.87 |

| Yes | 17.0 | 8.3 | 27.5 | 1.95 | 2.59 |

|

| |||||

| Depression | |||||

| No | 14.8 | 7.4 | 24.2 | 0.78 | 1.01 |

| Yes | 14.5 | 7.1 | 23.9 | 1.74 | 2.28 |

|

| |||||

| Census region | |||||

| Northeast | 11.9 | 5.2 | 20.5 | 0.78 | 1.11 |

| Midwest | 14.0 | 6.9 | 23.4 | 1.27 | 1.45 |

| South | 15.9 | 8.4 | 25.3 | 1.33 | 1.81 |

| West | 16.2 | 7.7 | 26.7 | 1.07 | 1.44 |

|

| |||||

| Emergency department visit for injury‡ | |||||

| No | 13.7 | 6.7 | 22.7 | 1.16 | 1.53 |

| Yes | 23.7 | 12.6 | 35.8 | 1.14 | 1.42 |

Long-term opioid use was defined as 6 months of days of opioids supplied in the 12 months after an index emergency department visit, excluding the first 30 days after the index emergency department visit.

The number of chronic conditions among 11 possible conditions is shown. These conditions are the following: acute myocardial infarction, Alzheimer’s dementia, atrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, depression, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.

An emergency department visit for an injury was defined as any emergency department visit with an “E” code associated with an injury (according to the codes in the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision). Of patients who visited an emergency department for a reason other than an injury, 195,651 saw low-intensity prescribers and 144,895 saw high-intensity prescribers. Of patients who visited an emergency department because of an injury, 20,027 saw low-intensity prescribers and 17,056 saw high-intensity prescribers.

The hypothetical long-term effect of filling an initial opioid prescription after an emergency department visit versus not filling a prescription was estimated to approximate the number of patients who would need to be prescribed an initial opioid for one patient to become a long-term user. A definition of “number needed to harm” is provided in the Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix.29

We performed additional sensitivity analyses to address the possibility of selection bias and sensitivity to design assumptions (details are provided in the Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix). These analyses included an alternative exposure in which intensity was defined according to the median dose of opioid prescription filled after an emergency department visit, as described above. Replicating our results with an alternative definition of exposure that operates through a similar causal pathway (increased opioid exposure) could argue against selection bias, particularly if the two exposures (dose and frequency of opioid prescribing) are minimally correlated.

All analyses were performed with the use of Stata software, version 14.1 (StataCorp). The 95% confidence intervals around reported estimates reflect 0.025 in each tail, or P values no higher than 0.05.

RESULTS

Our sample consisted of 215,678 patients treated by a low-intensity opioid prescriber and 161,951 patients treated by a high-intensity opioid prescriber during an index emergency department visit. Overall, the characteristics of patients treated by high-intensity opioid prescribers were similar to those of patients treated by low-intensity prescribers, although several differences were significant given the large sample size (Table 1). Diagnoses in patients seen by high-intensity prescribers and those seen by low-intensity prescribers were similar (P = 0.87 by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for differences in the distribution of 300 CCS groups, according to prescriber group [Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix; for distribution of the top 25 of 300 CCS diagnosis groups, according to prescriber group, see Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix]).

On average, rates of opioid prescribing between low-intensity prescribers and high-intensity prescribers varied by a factor of 3.3 within the same hospital (7.3% vs. 24.1% of emergency department visits, P<0.001) (Table 2 and Fig. 1A). Across all subgroups, prescribing rates among high-intensity prescribers were triple those among low-intensity prescribers. The highest average rate was seen among patients who visited the emergency department with an injury (23.7%) (Table 2). There was minimal correlation between physicians’ prescribing rates and the median initial dose of an opioid prescription that was filled (r=−0.08) (Fig. S3 and Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix) or type of opioid prescribed (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 1. Prescribing Rates and Adjusted Odds Ratios for Long-Term Opioid Use, According to Quartile of Physician Opioid Prescribing.

Panel A shows rates of opioid prescribing by emergency physicians according to within-hospital quartile. I bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Panel B shows the adjusted odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for rates of long-term opioid use, according to quartile of physician opioid prescribing. Physicians in each quartile were compared with those in the lowest prescribing quartile. Odds ratios were estimated with the use of logistic-regression models.

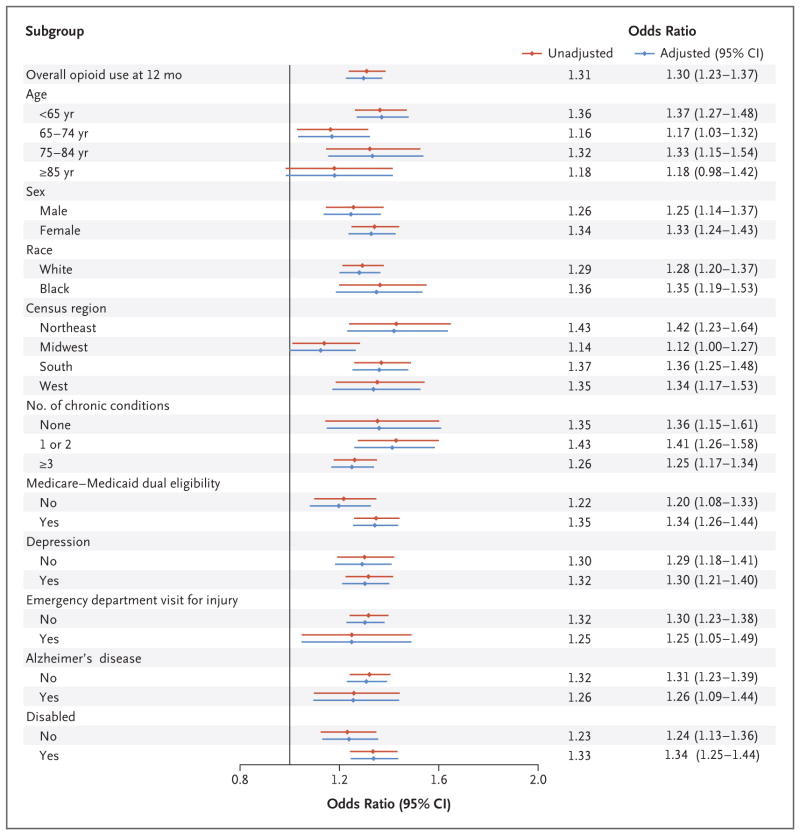

Overall, long-term opioid use at 12 months was significantly higher among patients treated by high-intensity prescribers than among patients treated by low-intensity prescribers (1.51% vs. 1.16%; unadjusted odds ratio, 1.31; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24 to 1.39) (Table 2 and Fig. 2). After adjustment, there was minimal change in this difference (adjusted odds ratio, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.23 to 1.37). This finding corresponds to a number needed to harm of 48 patients receiving an opioid prescription to theoretically lead to 1 excess long-term opioid user.

Figure 2. Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratios for Long-Term Opioid Use, According to Treatment by High-Intensity or Low-Intensity Opioid Prescriber.

All unadjusted odds ratios were estimated with the use of bivariate logistic regression with the occurrence of long-term opioid use as the dependent variable and exposure to a high-intensity provider as the key explanatory variable. All adjusted models had further adjustment for the patients’ age, sex, race or ethnic group, Medicare–Medicaid dual eligibility, and disability status and the presence of 11 chronic conditions.

We observed a stepwise increase in long-term opioid use with exposure to physicians in each quartile of opioid prescribing frequency. As compared with the first (low-intensity) quartile, patients treated by physicians in the second quartile had an adjusted odds ratio for long-term opioid use of 1.10 (95% CI, 1.04 to 1.16) and patients treated by physicians in the third quartile had an adjusted odds ratio of 1.19 (95% CI, 1.12 to 1.25) (Fig. 1B, and Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). Differences in long-term opioid use between patients treated by high-intensity prescribers and those treated by low-intensity opioid prescribers were consistent across subgroups, with minimal change after multivariable adjustment (Fig. 2).

Rates of opioid-related hospital encounters and encounters for fall or fracture were significantly higher in the 12 months after an index emergency department visit among patients treated by high-intensity opioid prescribers than among patients treated by low-intensity opioid prescribers (rates of any opioid-related encounter, 9.96% vs. 9.73%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.05; P = 0.02; rates of encounters for fall or fracture, 4.56% vs. 4.28%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.11; P<0.001) (Table 3). There was no significant difference in 12-month rates of overall hospital encounters or non–opioid-related encounters. Assessment of rates of short-term emergency department revisits for possible evidence of undertreated pain showed that rates of 14-day and 30-day repeat emergency department visits with the same primary diagnosis as the index visit were similar in the two prescriber groups (P>0.07) (Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 3.

Hospital Encounters within 12 Months after an Index Emergency Department Visit to a Low-Intensity or High-Intensity Opioid Prescriber.*

| Type of Hospital Encounter | 12-Mo Encounter Rate | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)† | P Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients Treated by Low-Intensity Prescriber (N = 215,678) | Patients Treated by High-Intensity Prescriber (N = 161,951) | |||

| % of patients | ||||

| Any hospital encounter | 60.5 | 60.3 | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.13 |

|

| ||||

| Any hospitalization | 46.1 | 45.8 | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.15 |

|

| ||||

| Any emergency department visit | 57.4 | 57.1 | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.07 |

|

| ||||

| Any opioid-related hospital encounter | 9.73 | 9.96 | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||

| Fall or fracture | 4.28 | 4.56 | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Constipation | 4.16 | 4.11 | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.44 |

|

| ||||

| Respiratory failure | 2.04 | 2.01 | 0.98 (0.94–1.03) | 0.46 |

|

| ||||

| Opioid poisoning | 0.07 | 0.10 | 1.40 (1.12–1.74) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Any selected non–opioid-related hospital encounter | 11.77 | 11.75 | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 0.85 |

|

| ||||

| Hyperglycemia | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.99 (0.87–1.14) | 0.93 |

|

| ||||

| Urinary tract infection | 1.08 | 1.13 | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | 0.17 |

|

| ||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 6.48 | 6.39 | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | 0.24 |

|

| ||||

| Stroke | 4.12 | 4.08 | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.52 |

A hospital encounter refers to a hospitalization or an emergency department visit. Definitions are provided in the Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix. CI denotes confidence interval.

Adjusted odds ratios and P values were estimated with the use of logistic-regression models with occurrence of an opioid-related hospitalization in the 12 months after an emergency department visit as the dependent variable. The key covariate was an indicator for being seen by a high-intensity or a low-intensity prescriber. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnic group, Medicare–Medicaid dual eligibility, and the presence of 11 chronic conditions.

We replicated the main analysis described above in multiple other sensitivity analyses, including one that used a propensity score–matched cohort (see the Results section in the Supplementary Appendix), although the finding of increased hospital encounters for falls or fractures with the use of propensity score matching (P = 0.05) and with the use of CCS category fixed effects (P = 0.12) was not significant (Table S6 in the Supplementary Appendix). In analyses in which physicians were categorized as being high or low “dose intensity” prescribers, we found increased odds of long-term opioid use among patients treated by high dose-intensity prescribers (odds ratio, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.46) (Table S6 and Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Appendix).

DISCUSSION

In a large, national sample of patients enrolled in Medicare Part D who received care in an emergency department and who had not used prescription opioids in the 6 months before the visit to the emergency department, we found substantial variation in the opioid prescribing patterns of emergency physicians within the same hospital. The intensity of a physician’s opioid prescribing was positively associated with the probability that a patient would become a long-term opioid user over the subsequent 12 months. Although our study was observational, we sought to minimize selection bias by comparing the characteristics of patients seen by different emergency physicians within the same hospital. The association between physician prescribing rates and increased long-term opioid use was consistent across numerous subgroups and across all quartiles of physician prescribing in a dose–response pattern.

It is commonly thought that opioid dependence often begins through an initial, possibly chance, exposure to a physician-prescribed opioid, although data from studies to empirically evaluate this claim are lacking. Our results provide evidence that this mechanism could drive initiation of long-term opioid use through either increased rates of opioid prescription or prescription of a high, versus a low, dose of opioid. Although causality cannot be established from this observational study, if our results represent a causal relationship, for every 48 patients prescribed a new opioid in the emergency department who might not otherwise use opioids, 1 will become a long-term user; this is a low number needed to harm for such a common therapy.

Of course, prescriptions provided by other physicians in the months after an emergency department visit are necessary for long-term opioid use to take hold. Conversion to long-term use may be driven partly by clinical “inertia” leading outpatient clinicians to continue providing previous prescriptions. Such clinical inertia may affect only a narrow segment of the population; this could explain why rates of initial opioid prescribing may vary by a factor of three, whereas long-term use varies by only approximately 30%. It is important to acknowledge that patients treated by high-intensity opioid prescribers may have disproportionately required appropriate opioid therapy, although some of the variation we observed in rates of opioid prescribing may also indicate overuse. If differences in appropriate use were a major driver of variation in prescribing, we may have expected increased rates of short-term emergency department revisits due to inadequately treated pain among the low-intensity prescriber groups. However, we did not find a difference in such rates between prescriber groups; this suggests that increased opioid prescribing did not prevent revisits to the emergency department.

Our results are unlikely to be explained by selection bias for several reasons. First, our analysis focused on variation in opioid prescribing of emergency physicians within the same hospital; these physicians are unlikely to select or attract systematically different patient populations. Second, even though there were small differences in characteristics between patients treated by the two prescriber groups, adjustment for these characteristics did not change our results with respect to long-term opioid use. We also replicated our results in a range of sensitivity analyses, and the case mix of emergency department visits across 300 diagnosis categories was statistically indistinguishable between groups. In addition, we replicated our results with an alternative exposure definition based on opioid dose; this exposure was minimally correlated with the frequency of opioid prescribing by physicians.

Our study has several limitations. Most important, this is an observational study and cannot be interpreted as causal, although our findings were robust in several sensitivity analyses addressing selection bias. Second, since we could not observe whether an opioid prescription was appropriate, our ability to quantify the extent of overuse of opioids was limited. Third, because we focused on Medicare patients with Part D enrollment and emergency department visits, our results may not be generalizable to other populations. However, the growing prevalence of opioid misuse among the elderly makes this an important group to study.16,24 Fourth, the association between high-intensity opioid prescribers and opioid-related hospital encounters within 12 months after the index emergency department visit was small and not significant in some sensitivity analyses. In addition, for outcomes with a significant association, the absolute difference in rates of hospital encounters between groups was small (e.g., an absolute difference of 0.23 percentage points for any opioid-related encounter) (Table 3). Therefore, we have weaker evidence to support this association than our results on long-term opioid use, and if it were causal, the clinical magnitude of this association would be small. Fifth, we were unable to unequivocally attribute an opioid prescription to an emergency physician; however, our analyses were robust with respect to a stricter threshold of 3 days to fill a prescription for opioids from an emergency physician.16 Finally, our statistical tests do not account for the false positive rate associated with multiple secondary analyses; therefore, P values should be regarded as exploratory.

In conclusion, we found variation by a factor of more than three in rates of opioid prescribing by emergency physicians within the same hospital and increased rates of long-term opioid use among patients treated by high-intensity opioid prescribers. These results suggest that an increased likelihood of receiving an opioid for even one encounter could drive clinically significant future long-term opioid use and potentially increased adverse outcomes among the elderly. Future research may explore whether this variation reflects overprescription by some prescribers and whether it is amenable to intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (NIH) (NIH Director’s Early Independence Award, 1DP5OD017897-01, to Dr. Jena).

Footnotes

Dr. Barnett reports serving as medical advisor to and holding stock in Ginger.io; and Dr. Jena, receiving consulting fees from Pfizer, Hill-Rom Services, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and Precision Health Economics. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers — United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1487–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prescription opioid overdose data. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. ( http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/overdose.html) [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. 2014 May 14; ( https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse)

- 4.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Hospital inpatient utilization related to opioid overuse among adults, 1993–2012. 2014 Aug; ( https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb177-Hospitalizations-for-Opioid-Overuse.jsp) [PubMed]

- 5.Vestal C. Older addicts squeezed by opioid epidemic. Stateline. 2016 Jul 26; ( http://pew.org/2asv3TO)

- 6.Dufour R, Joshi AV, Pasquale MK, et al. The prevalence of diagnosed opioid abuse in commercial and Medicare managed care populations. Pain Pract. 2014;14(3):E106–E115. doi: 10.1111/papr.12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makris UE, Abrams RC, Gurland B, Reid MC. Management of persistent pain in the older patient: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;312:825–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller M, Stürmer T, Azrael D, Levin R, Solomon DH. Opioid analgesics and the risk of fractures in older adults with arthritis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:430–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, Lee J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. The comparative safety of analgesics in older adults with arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1968–76. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buckeridge D, Huang A, Hanley J, et al. Risk of injury associated with opioid use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1664–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Neil CK, Hanlon JT, Marcum ZA. Adverse effects of analgesics commonly used by older adults with osteoarthritis: focus on non-opioid and opioid analgesics. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10:331–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler MM, Ancona RM, Beauchamp GA, et al. Emergency department prescription opioids as an initial exposure preceding addiction. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68:202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank R. Targeting the opioid drug crisis: a Health and Human Services initiative. Health Affairs Blog. 2015 Apr 3; ( http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/04/03/targeting-the-opioid-drug-crisis-a-health-and-human-services-initiative/)

- 14.Department of Health and Human Services Behavioral Health Coordinating Committee. Addressing prescription drug abuse in the United States: current activities and future opportunities. 2014 ( https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/hhs_prescription_drug_abuse_report_09.2013.pdf)

- 15.Kuo Y-F, Raji MA, Chen N-W, Hasan H, Goodwin JS. Trends in opioid prescriptions among Part D Medicare recipients from 2007 to 2012. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):221.e21–221.e30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jena AB, Goldman D, Karaca-Mandic P. Hospital prescribing of opioids to Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:990–7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poon SJ, Greenwood-Ericksen MB. The opioid prescription epidemic and the role of emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:490–5. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamayo-Sarver JH, Dawson NV, Cydulka RK, Wigton RS, Baker DW. Variability in emergency physician decision making about prescribing opioid analgesics. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:483–93. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299:70–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoppe JA, Nelson LS, Perrone J, Weiner SG. Opioid prescribing in a cross section of US emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66(3):253–259. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315:1624–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:85–92. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braden JB, Russo J, Fan M-Y, et al. Emergency department visits among recipients of chronic opioid therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1425–32. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jena AB, Goldman D, Weaver L, Karaca-Mandic P. Opioid prescribing by multiple providers in Medicare: retrospective observational study of insurance claims. BMJ. 2014;348:g1393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. ( https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp)

- 26.Meara E, Horwitz JR, Powell W, et al. State legal restrictions and prescription-opioid use among disabled adults. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:44–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1514387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Institute of Standards and Technology. Kolmogorov-Smirnov Goodness-of-Fit Test. 2013 ( http://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/handbook/eda/section3/eda35g.htm)

- 28.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48:817–38. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angrist JD, Pischke J-S. Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.