Abstract

The gut microbiota is involved in various physiological functions, and disturbances in the host-microbiome have been proven to contribute to the dysfunction of gut; however, whether microbiota participates in the pathogenesis of constipation remains unclear. In this study, we extracted and analyzed microbiota in feces from constipated donors who had undergone effective therapy with fecal microbiota transplantation, transplanted microbiota into pseudo-germ-free mice, and measured gut motility. These mice presented with lower pellet frequency and water percentage, smaller pellet size, delayed gastrointestinal transit time, and weaker spontaneous contractions of colonic smooth muscle. To determine the mechanism underlying delayed gut motility, microbial metabolites were measured. Short chain fatty acids and secondary bile acids were decreased in mice receiving microbiota from constipated donors. Moreover, the compositional changes of gut microbiota in constipated patients were identified, including the operational taxonomic unit, and the species richness and α diversity were much greater than those in healthy volunteers. These findings suggest that alterations of the microbiome might affect gut motility via altered microbial-derived metabolites in the development of constipation, and the restoration of disturbed microbiota might improve the clinical phenotype. This study indicates that regulating the intestinal environment may be a novel therapy strategy for constipation.

Introduction

Chronic constipation is a functional bowel disorder with a high incidence worldwide, affecting 14% of adults and specifically almost 36% of the elderly1. According to Rome IV criteria, chronic constipation is characterized by various symptoms of difficult, infrequent, or incomplete defecation predominate2. There are three broad categories in chronic constipation including normal-transit constipation, slow-transit constipation (STC), and defecatory or rectal evacuation disorders3. Among these, STC is the majority category characterized by the markedly increased colonic transit time3.

Chronic constipation is a multifactorial disorder including a complex pathogenesis that still warrants further discussion. Earlier investigations have focused on the enteric nervous system (ENS) and interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC). In patients with STC, both the amount and morphology of ENS or ICC are altered, which may play a crucial role in the pathophysiology of colorectal motility disorders4. For instance, the myenteric plexus showed a reduced ganglionic density and size (moderate hypoganglionosis) compared with those in the control group5. In addition, colonic endocrine cells, which play a pivotal role in the regulation of colon motility, absorption, and secretion, were changed in STC6. There are also other studies reporting changes in autonomic dysfunction, morphologic changes in the myenteric and submucosal plexus, and reduced neurotransmitter levels (such as 5-HT, NO and VIP) in some patients with STC2, 7. However, these studies on STC can only explain some cases, and have focused less on the intestinal contraction itself. Therefore, it is also necessary to conduct research on the contractile property in constipation.

Recently, increasing studies have indicated that the gut microbiota plays a key role in health, and microbiota affects various activities of host physiology, including gut motility8, 9. The microbiota is dominated by bacteria belonging to the phyla Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria. The microbiota inhabits the different regions of the digestive tract, and the colon is most densely populated10. Interestingly, accumulating evidence has demonstrated that the composition of the intestinal microbiota is different between constipated patients and healthy controls11–14. It was found that the composition of the colonic mucosal microbiota differed between constipated patients and controls, such that genera from Bacteroidetes were more abundant in the colonic mucosal microbiota of patients with constipation15. In the clinic, stool consistency is categorized by the Bristol Stool Scale (BSS) scores. Stool forms 1 and 2 are strongly associated with slower transit2. Vandaputte et al.16 reported that stool consistency was strongly associated with all known major microbiome markers. In their study, the microbiome markers were negatively related to species richness, while they were positively correlated with the Bacteroidetes:Firmicutes ratio, and negatively related to Akkermansia and Methanobrevibacter abundance. In addition, the abundance of methanogens (such as Methanobrevibacter) was increased in harder stools, a finding that was consistent with the elevated methane production in patients with chronic constipation, and methane was suggested to slow down gut motility17. These pathophysiological changes in constipated patients raise the reflections on whether striking changes in the fecal flora could be one cause of constipation. On the other hand, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has been proposed as a therapeutic approach for functional gastrointestinal disorders by the reestablishment of the intestinal microenvironment. It was demonstrated that FMT was safe and effective for chronic constipation with clinical improvement and remission rates were 66.7% and 42.9% at our hospital18. However, these studies on the relationship between microbiota and gut motility did not discuss whether striking changes in the fecal flora are the cause of constipation. Therefore, it is necessary to perform systemic research on the role of microbiota in constipation.

It is well-documented about the role of gut microbiota in metabolism. Gut microbiota can impact stool habit, gastrointestinal transit, and stool weight19. There are two important luminal factors modulated by the microbiota, including short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and bile acids (BAs). SCFAs were demonstrated to modify colonic motility through nerves and polypeptide YY release in rats20. Additionally, SCFAs could stimulate 5-HT3 receptors located on the vagal sensory fibers to release of 5-HT from enterochromaffin cells (ECs), thus accelerating colonic transit21. BAs, another microbial-derived metabolite, was revealed to stimulate the release of 5-HT and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) from ECs and intrinsic primary afferent neurons via activating TGR5, which led to the peristaltic reflex22. Interestingly, secondary BAs were proposed to directly act on ECs to synthetize 5-HT by elevating colonic TPH1 expression23. 5-HT was reported to induce the contraction of colonic myocytes due to the release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum by activating 5-HT3 receptors and the inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate pathway24.

To answer whether striking changes of gut microbiota between chronic constipation and health do harm to the host, we first selected six STC donors who received the clinical therapy of FMT effectively. Next, we transplanted fecal microbiota from donors to mice and monitored the symptoms of constipation. Because microbiota metabolism of dietary substrates has been speculated to be associated with gut motility10, 25, 26, we measured the related molecules, such as SCFAs and BAs, in mice to ascertain the possible mechanism of microbiota from STC in gut motility.

Results

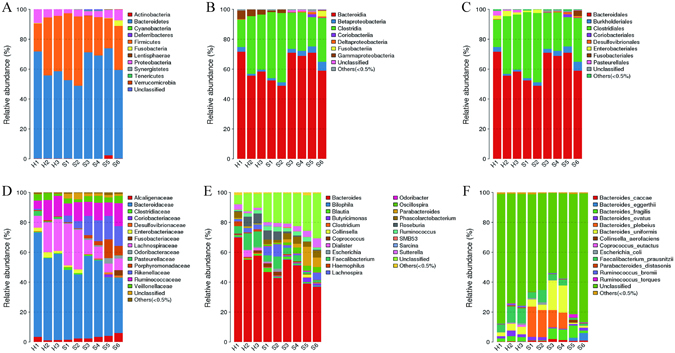

Donors’ characteristics and improved efficacy of FMT in STC

Six STC and three healthy donors were eligible for inclusion18. All of the enrolled STC donors received clinical therapy of FMT effectively. Their mean age was 57.2 years (range: 48–65 years), and the mean duration of constipation was 13.7 years (range: 6–20 years). The microbiota analyses showed that the operational taxonomic unit (OTU) of constipated patients was greater than that of healthy donors (180.2 ± 13.6 vs 123.7 ± 3.2, respectively; p = 0.021), with increased species richness (Chao index, 186.3 ± 14.2 vs 143.3 ± 10.9, respectively; p = 0.082) and α diversity (Shannon index, 3.54 ± 0.06 vs 3.06 ± 0.06, respectively; p = 0.006). The baseline demographics of the donors are presented in Table 1. The fecal microbiota of the healthy and STC donors presented a difference in their composition (Fig. 1). After treatment with FMT, it showed an increased stool frequency from 1.6 ± 0.2 to 5.0 ± 0.4 per week (p < 0.05), and an improved stool consistency from 2.0 ± 0.3 to 3.3 ± 0.2 (p < 0.05) in patients. In addition, the patient assessment of constipation symptoms questionnaire (PAC-SYM) and gastrointestinal quality-of-life index (GIQLI) scores were improved at 12 weeks after FMT. Compared with pre-treatment, colonic transit time (CTT) improved from 81.9 ± 9.5 to 53.3 ± 11.2 hours (p < 0.05). The details of the efficacy in STC patients receiving FMT are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of included donors at baseline (Healthy donor = 3, STC donor = 6).

| Donor No. | Sex (F/M) | Age (y) | Weight (kg) | Height (m) | BMI (18.5–25) | Disease Duration (y) | NO. BM Per Week Before Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STC donor 1 | F | 55 | 60 | 1.65 | 22.0 | 15 | 1 |

| STC donor 2 | F | 65 | 65 | 1.60 | 25.4 | 20 | 2 |

| STC donor 3 | M | 64 | 68 | 1.68 | 24.1 | 18 | 2 |

| STC donor 4 | M | 56 | 60 | 1.70 | 20.8 | 15 | 1.5 |

| STC donor 5 | M | 55 | 55 | 1.60 | 21.5 | 8 | 1.5 |

| STC donor 6 | F | 48 | 47 | 1.58 | 18.8 | 6 | 1.5 |

| Health donor 1 | F | 22 | 50 | 1.60 | 19.5 | 0 | 7 |

| Health donor 2 | F | 24 | 55 | 1.65 | 20.2 | 0 | 7 |

| Health donor 3 | F | 23 | 60 | 1.62 | 22.9 | 0 | 7 |

F, female; M, male; BMI, body mass index; BM, bowel movement; STC, slow transit constipation.

Figure 1.

Microbiota composition of healthy donors and STC donors. (A) Phylum level; (B) Class level; (C) Order level; (D) Family level; (E) Genus level; (F) Species level. STC: slow transit constipation; Group H (n = 3): healthy donor; Group S (n = 6): slow transit constipation donor.

Table 2.

Outcome measures in constipated patients with fecal microbiota transplantation (n = 6).

| Outcomes | Times | Results | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of BM/week | Pre-treatment | 1.6 ± 0.2 | <0.001 |

| 12 week | 5.0 ± 0.4 | ||

| Stool consistency score | Pre-treatment | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 0.0025 |

| 12 week | 3.3 ± 0.2 | ||

| PAC-SYM score | Pre-treatment | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 0.031 |

| 12 week | 1.5 ± 0.6 | ||

| GIQLI score | Pre-treatment | 80.3 ± 11. 6 | 0.009 |

| 12 week | 122.5 ± 15.7 | ||

| CTT (hours) | Pre-treatment | 81.9 ± 9.5 | 0.012 |

| 12 week | 53.3 ± 11.2 |

BM, bowel movement; PAC-SYM, Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms; GIQLI, Gastrointestinal Quality-of-Life Index; CTT, colonic transit time.

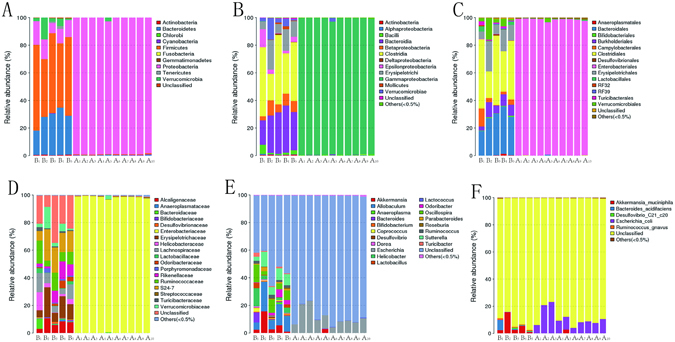

Composition of the intestinal microbiome in pseudo-germ-free mice

Pseudo-germ-free mice were produced by broad-spectrum antibiotics treatment for 4 weeks27, 28. After antibiotics combination, the composition of commensal bacteria was largely changed (Fig. 2). The OTU of mice decreased significantly from 341.0 ± 19.1 to 74.8 ± 2.6 (p < 0.001). Taxonomically, the abundance of most intestinal microbiota decreased significantly in all levels as shown in Fig. 2(A–F) (Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, and Species). The species richness (Chao index) decreased from 354.3 ± 19.2 to 98.3 ± 4.8 (p < 0.001), and α diversity (Shannon index) decreased from 4.0 ± 0.2 to 0.5 ± 0.1 (p < 0.001). Because most of the resident intestinal microbiota was depleted, pseudo-germ-free mice could be used in mouse humanization studies when gnotobiotic facilities were limited.

Figure 2.

Microbiota composition of antibiotics-treated mice at every level. (A) Phylum level; (B) Class level; (C) Order level; (D) Family level; (E) Genus level; (F) Species level. Group B (n = 5): SPF mice without antibiotics; Group A (n = 10): SPF mice with antibiotics.

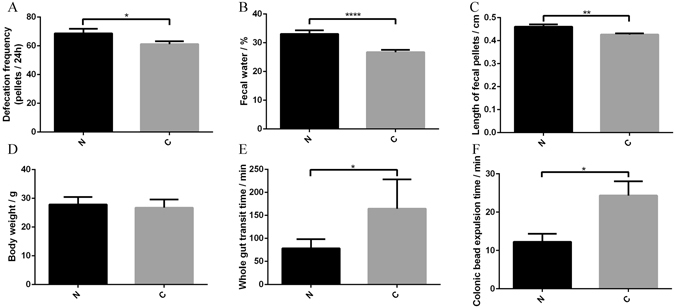

Fecal microbiota from the STC donors affects the fecal parameters, total gastrointestinal transit, and colonic transit in pseudo-germ-free mice

After 8 weeks by gavage with fecal microbiota from STC and healthy donors, both fecal parameters and gut motility were affected. Pseudo-germ-free mice receiving from STC donors had lower pellet frequency (68.6 ± 3.2 vs 61.1 ± 2.1 pellets/24 hours, p = 0.049), lower water percentage (33.0 ± 1.3 vs 26.7 ± 0.8%, p < 0.001), and smaller pellet size (0.46 ± 0.01 vs 0.42 ± 0.01 cm, p = 0.002) than mice receiving fecal microbiota from healthy donors (Fig. 3A–C). However, the body weight of the two groups was not different (27.8 ± 0.7 vs 26.7 ± 0.6 g, p = 0.214) (Fig. 3D). The total gastrointestinal transit time was greater in mice from STC donors, indicating significantly slower transit (78.0 ± 10.1 vs 164.2 ± 28.5 min, p = 0.037) (Fig. 3E). The colonic transit test was longer in mice from STC donors, indicating that fecal microbiota from STC donors caused slower colonic propulsion in mice (12.3 ± 2.1 vs 24.3 ± 3.7 min, p = 0.029) (Fig. 3F). Therefore, mice showed typical symptoms of constipation after receiving intestinal microbiota from STC donors.

Figure 3.

Transplantation of intestinal microbiota from STC donors has effects on defecation frequency (Group N = 20, Group S = 30) (A), fecal water content (Group N = 20, Group S = 30) (B), length of fecal pellets (Group N = 20, Group S = 30) (C), body weight after experiments (Group N = 20, Group S = 30) (D), total gastrointestinal transit time (Group N = 5, Group S = 10) (E), and colonic transit time (Group N = 5, Group S = 10) (F). Data represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Group N: mice receiving fecal microbiota from healthy donor; Group C: mice receiving fecal microbiota from STC donors. STC: slow transit constipation.

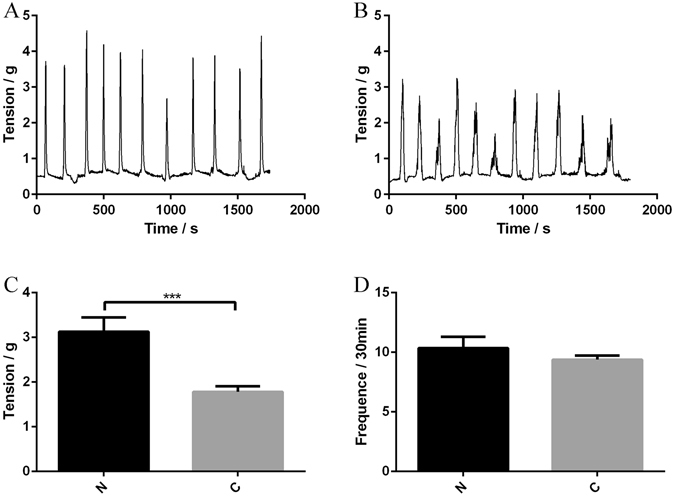

Contractility of proximal colonic muscle

As pseudo-germ-free mice receiving fecal microbiota from STC donors had a decreased fecal output and delayed gut transit, it raised the possibility that the spontaneous contraction of intestinal smooth muscle might be affected by fecal microbiota from STC donors. After receiving fecal microbiota from STC donors, the average spontaneous phasic contractions of colonic longitudinal smooth muscle were inhibited. The tension decreased significantly from 3.12 ± 0.32 to 1.78 ± 0.12 g (p < 0.001), while the waveform did not change significantly (10.3 ± 1.0 vs 9.4 ± 0.3/30 min, p = 0.259) (Fig. 4). Therefore, microbiota from STC donors might inhibit the contractions of colonic smooth muscle in patients that could result in the lack of gastrointestinal motility.

Figure 4.

Transplantation of fecal microbiota from STC donors regulates colonic contractility (Group N = 6, Group S = 12). Recordings were made of spontaneous phasic contractions of proximal colon. Representative recordings from mice receiving fecal microbiota of healthy donors (A) and mice receiving fecal microbiota of STC donors (B). Tension (C) and frequency (D) normalized to basal values in mice receiving fecal microbiota from healthy and STC donors. Data represent the mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001. Group N: mice receiving fecal microbiota from healthy donor; Group C: mice receiving fecal microbiota from STC donors. STC: slow transit constipation.

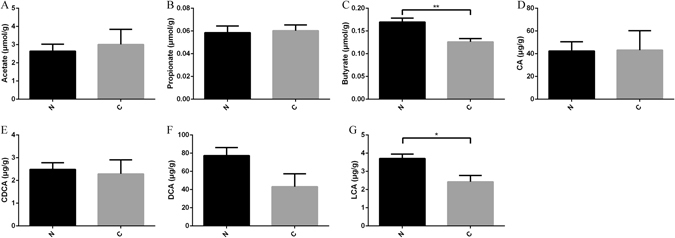

The host metabolism in the colon is influenced by fecal microbiota from STC donors

After 8 weeks of colonization with fecal microbiota from STC and healthy donors, SCFAs and BAs in the cecum were analyzed, respectively. SCFAs are generated in the colon as a result of the bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber and resistant starch, which mainly include acetate, propionate, and butyrate29. Bile acids are endogenous molecules synthesized from cholesterol in hepatocytes to form primary BAs, which are then metabolized by the gut microbiota to form secondary BAs25, 30. Our results showed that butyrate levels were decreased significantly in mice treated with STC donors (0.17 ± 0.01 vs 0.13 ± 0.01 μmol/g, p = 0.008) (Fig. 5). However, there was no significant difference in the levels of acetate (2.64 ± 0.4 vs 3.01 ± 0.8 μmol/g, p = 0.710) or propionate (0.058 ± 0.006 vs 0.060 ± 0.005 μmol/g, p = 0.840) (Fig. 5). The analysis of the BA levels showed that there was no significant difference in primary BAs (cholic acid (CA): 42.27 ± 8.23 vs 43.12 ± 17.12 μg/g, p = 0.966; chenodeoxycholic (CDCA): 2.48 ± 0.29 vs 2.28 ± 0.62 μg/g, p = 0.779) (Fig. 5), but there was a tendency towards decreased concentrations of secondary BAs. The deoxycholic acid (DCA) levels in mice from STC donors were lower than those in mice from healthy donors (77.23 ± 8.87 vs 43.04 ± 14.18 μg/g, p = 0.083), and the lithocholic acid (LCA) levels were also decreased significantly in mice from STC donors (3.70 ± 0.25 vs 2.42 ± 0.35 μg/g, p = 0.025) (Fig. 5). Therefore, microbiota from STC donors that affected gut motility might be due to changes in host metabolism, similar to SCFAs and BAs.

Figure 5.

Transplantation of microbiota from STC donors altered host metabolism in colon (Group N = 5, Group S = 5). SCFAs (acetate, propionate and butyrate) (A–C), primary BAs (CA and CDCA), and secondary BAs (DCA and LCA) levels (D–G) change in mice receiving fecal microbiota from STC donors. Data represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Group N: mice receiving fecal microbiota from healthy donor; Group C: mice receiving fecal microbiota from STC donors. STC: slow transit constipation; SCFA, short chain fatty acids; CA, cholic acid; CDCA, chenodeoxycholic; DCA, deoxycholic acid; LCA, lithocholic acid.

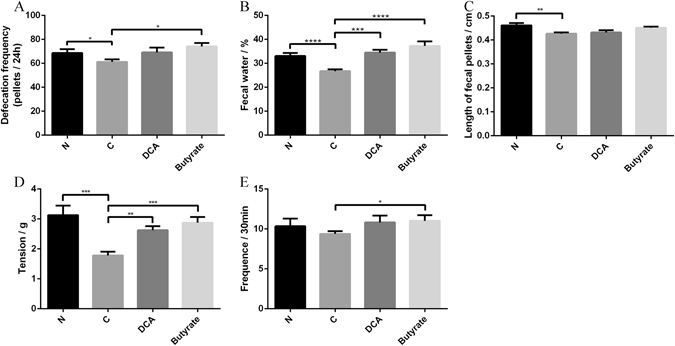

Supplementation with butyrate and secondary BAs alter the motility in mice

After supplementation with butyrate and DCA in drinking water for 2 weeks, the defecation frequency, fecal water content, length of fecal pellets and colonic contractility were examined in the mice (Fig. 6). Compared with mice from STC donors, DCA-treated mice had a higher water percentage (26.7 ± 0.8 vs 34.5 ± 1.2%, p < 0.001) and increased tension of contractility significantly (1.78 ± 0.12 vs 2.62 ± 0.13 g, p = 0.001), but there was no difference in the pellet frequency (61.1 ± 2.1 vs 69.0 ± 4.1 pellets/24 hours, p = 0.172), pellet size (0.42 ± 0.01 vs 0.43 ± 0.01 cm, p = 0.717) and frequency of contractility (9.4 ± 0.3 vs 10.8 ± 0.9/30 min, p = 0.078). In addition, butyrate-treated mice had a higher pellet frequency (61.1 ± 2.1 vs 74.0 ± 2.9 pellets/24 hours, p = 0.027), higher water percentage (26.7 ± 0.8 vs 37.2 ± 1.9%, p < 0.001), and increased tension (1.78 ± 0.12 vs 2.87 ± 0.19 g, p < 0.001) and frequency (9.4 ± 0.3 vs 11.0 ± 0.7/30 min, p = 0.031) of contractility, but there was no difference in the pellet size (0.42 ± 0.01 vs 0.45 ± 0.01 cm, p = 0.068).

Figure 6.

DCA and butyrate supplements have effects on defecation frequency (A), fecal water content (B), length of fecal pellets (C), and colonic contractility (D: tension; E: Frequency) of mice receiving fecal microbiota from STC donors (DCA mice = 6, Butyrate mice = 6). Data represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Group N: mice receiving fecal microbiota from healthy donor; Group C: mice receiving fecal microbiota from STC donors; Group DCA: mice receiving fecal microbiota from STC donors were treated with DCA; Group butyrate: mice receiving fecal microbiota from STC donors were treated with butyrate. STC: slow transit constipation; DCA: deoxycholic acid.

Discussion

It was gradually realized that establishing and maintaining a beneficial balance between intestinal microbiota and the human body are necessary for the normal functions of the intestine9. The dysbiosis will contribute to the pathogenesis of functional gastrointestinal disorders10. Therefore, it is essential to study the role of intestinal microbiota from STC patients in gut motility. In this study, the enrolled STC donors received FMT effectively, and the symptoms in STC patients were improved during follow-up. Next, pseudo-germ-free mice receiving fecal microbiota from STC donors were more likely to present constipation symptoms, including the hardness of stools, infrequent passage of stools, and poor gastrointestinal motility. In addition, microbiota metabolites in mice from STC donors were also changed in SCFAs and BAs. After supplementation with butyrate and DCA, some symptoms in mice from STC donors were reversed. This might be attributed to the disturbed intestinal microbiota that could change the host metabolism and affect gastrointestinal motility. Therefore, we concluded that aberrant gut microbiota composition in constipation might affect gut motility by altering host metabolism.

Commensal bacteria play a key role in the development and maintenance of intestinal sensory and motor functions31. Studies on germ-free mice showed that gastric emptying and gastrointestinal transit were significantly delayed compared with those in conventionally raised mice31. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron was reported to stimulate gut motility by increasing the expression of γ-aminobutyric, vesicle-associated protein-33 and enteric γ-actin32. Meanwhile, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum could accelerate intestinal transit by releasing neuromessengers, while Micrococcus luteus and Escherichia coli had an inhibitory effect33. After antibiotics, mice in the weekly fecal transfer treatments were fed by gavage for 8 weeks with fecal material from their respective donors. Using mice from STC donors, we herein showed that the symptoms of constipation could be replicated in mice. Recently, a growing body of work has implicated that the intestinal microbiota of constipated patients is altered11–14; for example, unclassified_Ruminococcaceae, Alistipes, and Oscillibacter were negatively correlated with the mean stool frequency34. Additionally, it has also been proven that human microbiota could promote the biosynthesis of 5-HT from colonic ECs to modulate gastrointestinal motility23. Therefore, our study indicated that normal microbiota might exert modulatory effects on gut motility.

A compelling set of relationships between microbiota metabolism and host physiology has emerged. SCFAs derived from the microbial fermentation of dietary fiber can directly inhibit histone deacetylases, activate G-coupled-receptors, and serve as energy substrates, thus affecting various aspects of physiological processes35. It has been reported that SCFAs stimulate the contractions of the intestine through an enteric cholinergic reflex26. Butyrate, one product of SCFAs, plays a strong regulatory role in microbial TLR-dependent sensing, which is implicated in gut motility by secreting PYY and GLP-136. In our results, the butyrate levels were significantly lower in mice from STC donors than in mice from healthy donors. After supplementation with butyrate, the results of mice from STC donors were reversed in pellet frequency, water percentage, and colonic contractility. Therefore, fecal microbiota from STC donors might regulate gut motility by affecting the production of SCFAs.

Another particularly versatile class of microbial-produced metabolites, bile acids, is produced from cholesterol in hepatocytes and is metabolized by gut microbiota in the intestine30, 37. Evidence has demonstrated that BAs also impact gut motility by the release of serotonin from ECs38–40. When mice are transplanted with the microbiota from humans representing diverse culinary traditions, microbially deconjugated bile acid metabolites were correlated with faster gut transit41. Collectively, it is probable that BAs activate ECs to produce serotonin in the colon, and then alter gut motility. In our results, we found that the secondary BA level was lower in mice from STC donors, indicating that the microbial metabolism of BAs in the colon was disturbed. Decreased levels of secondary BAs could reduce the release of 5-HT from ECs, thereby affecting gut motility. After supplementation with DCA, the results of mice from STC donors were reversed in the water percentage and colonic contractility. However, the microbial metabolism of BAs is different between mice and humans. The primary BAs in humans are CA and CDCA, which in rodents are CA and muricholic acid (MCA). Next, deconjugated primary BAs that enter the colon are metabolized through 7-dehydroxylation into secondary BAs, including DCA from CA and LCA from CDCA. In rodents, the primary murine MCA also results in the formation of murideoxycholic acid (MDCA) in addition to DCA and LCA. In humans, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is a secondary BA that is formed by 7α/β-isomerization of CDCA, and this process can be performed by Clostridium absonum 30, 42. Therefore, altered bile acid profiles and a different metabolism process may affect various signaling through bile acid receptors between mice and humans. Thus, the results of our study warrant further discussion when translating findings from mice to humans.

FMT has shown efficacy for various gastrointestinal disorders, such as Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). We previously suggested that FMT could increase bowel movements, improve the Wexner constipation score and GIQLI score in STC patients18. Studies have reported that in patients with recurrent CDI, the metabolism of bile salts and primary BAs to secondary BAs was disrupted, and FMT could result in the normalization of fecal bacterial community structure and could correct this abnormal metabolic composition43. FMT was also found to have a positive clinical response in ulcerative colitis, which was associated with successive colonization of donor-derived phylotypes44. Therefore, the mechanism of FMT might be the reestablishment of intestinal flora and abnormal microbiota metabolites in patients. Taken together, intestinal microbiota from STC donors was proven to affect gut motility, and the regulation of the intestinal microenvironment by FMT might be effective for constipated patients.

There are several limitations in this study. First, antibiotic treatment cannot completely remove the intestinal microbiota. Thus, it cannot be ruled out that some of the residual microbiota influence gut motility. Second, only six patients with slow transit constipation were enrolled, so we could not describe changes in the intestinal microbiota systematically. However, we plan to conduct a metagenomics analysis of intestinal microbiome in constipation in the future, with many more selected patients. Third, the observed changes in our study do not seem dramatic, possibly because gut motility is regulated by multiple signaling pathways. The intestinal microbiota might be just one of the causes. Thus, further work is necessary to clarify whether other pathways participate in the regulation of gut motility in constipation.

In summary, the results of this study have suggested that the colonization of the gut by microbiota from constipated donors might affect gut motility and stool consistency in mice through modulating host metabolism, and reestablishment of the intestinal microenvironment in constipated patients might be effective. The alterations of the microbiome in constipation, in turn, could affect the host, which might increase significant evidence for a novel treatment on fecal microbiota transplantation for constipated patients.

Materials and Methods

Healthy volunteers and STC donors

All procedures were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 80-23), revised in 1996, and were approved by the Experimentation Ethics Review Committee of Jinling Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University. Stool was collected from healthy donors that was previously used in a clinical fecal transplantation study in patients with STC, CDI, and IBD at our hospital18, 45, 46. Stool was collected and prepared from STC patients according to Rome IV (Table 1 for patients’ characteristics). The inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria were consistent with those in our previous study18. Fecal samples from both healthy donors and STC donors were collected for 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) gene sequencing.

Efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation for STC donors

STC donors were treated according to the standardized FMT procedure at our hospital18. Spontaneous complete bowel movements (SCBMs) per week, stool consistency, PAC-SYM, GIQLI, and CTT were measured at the twelfth week after FMT18. The STC donors were enrolled in the following animal experiments only if there was clinical improvement or remission with FMT. Patients and their families signed the informed consent, and the study was approved by the human ethics committee of Jinling Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University (2015NZKY-020).

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (6 to 7 weeks old) provided by the Model Animal Research Center at Nanjing University were adapted to environmental conditions for one week before experiments. All animals were group-housed and fed the same autoclaved chow and water ad libitum under a 12-hour light/dark cycle, with a constant temperature of 21–22 °C and humidity of 55 ± 5%. The experiments followed the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 80-23), revised in 1996, and were approved by the Experimentation Ethics Review Committee of Jinling Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University.

Antibiotic treatment

Mice (n = 80) were provided with drinking water containing broad-spectrum antibiotics (ampicillin, 1 g/L; neomycin sulfate, 1 g/L; metronidazole, 1 g/L; vancomycin, 500 mg/L; Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) for 4 weeks ad libitum47. Antibiotics were renewed every two days. After 4 weeks, stool samples from the experimental mice were collected in a sterile micro-tube, and then were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored in a −80 °C freezer until analysis.

Microbiota Preparations for Mice Colonization

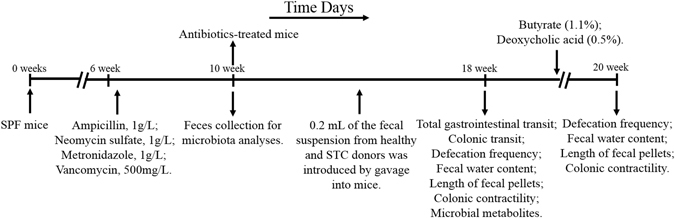

Healthy and STC microbiota were prepared by diluting 1 g of fresh human fecal samples in 10 mL of reduced PBS under anaerobic conditions48, 49. The fecal material was then suspended by vortexing, and 0.2 mL of the suspension was introduced by gavage into each mouse recipient. After depletion of gut commensal microflora27, 47, 50, antibiotics-treated mice were given fecal microbiota from donors by gavage once a week for 8 weeks during the colonization experiments. After colonization, some mice from the same cohorts were then treated with SCFAs (1.1% sodium butyrate) or secondary BAs (0.5% sodium deoxycholate) in drinking water for two weeks (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China), with water renewed every two days51, 52. A diagram of the study design is shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7.

Experimental design indicating treatment and sampling times. STC, slow transit constipation.

Total gastrointestinal transit

After fasting overnight with free access to water, the mice were fed a semiliquid solution (0.1 mL) containing Evans blue (5%) (E2129, Sigma) and methyl cellulose (1.5%) (M0262, Sigma) by gavage25. After gavage, fecal pellets were monitored at 10 min intervals for the presence of the first blue pellet. The time for the expulsion of the first blue pellet was determined.

Colonic transit

The mice were fasted overnight with free access to water. Colonic transit of mice was measured using a bead expulsion test25, 53. A 3-mm glass bead was inserted into the colon (2 cm proximal to the anal) using a plastic Pasteur lightly lubricated with lubricating jelly as described25, 53. The time until bead expulsion was measured.

Fecal parameter and macroscopic measurements

Freely feeding mice were observed for 24 hours, and the number of pellets was counted every two hours. Fecal water content was measured by comparing the weight of the pellets at the end of the experiment and after drying (24 hours at 60 °C). Finally, fecal dimensions of each mouse were measured. In addition, animals were weighed every week from the beginning to the end of the experiments. The mice were sacrificed by isoflurane overdose, and the whole intestine (from stomach to anus) was excised.

Analysis of smooth muscle contractility

Strips of longitudinal (6mm in length) muscle from the proximal colon were mounted in a 37 °C organ bath with a force transducer (MLT0202; AD Instruments, Spain) connected to a PowerLab (AD Instruments, Australia) recording device. Briefly, Ca2+-free HEPES-Tyrode (H-T) buffer (140.6 mmol/L NaCl, 2.7 mmol/L KCl, 1.0 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L HEPES, and 5.6 mmol/L glucose, pH 7.4) was used to wash out the lumen contents of proximal colon segments. Next, the segments were transferred to the organ bath and equilibrated in H-T buffer (137.0 mmol/L NaCl, 2.7 mmol/L KCl, 1.0 mmol/L MgCl2, 1.8 mmol/L CaCl2, 10 mmol/L HEPES, and 5.6 mmol/L glucose, pH7.4) for 15 minutes. The resting tension was set to approximately 0.5 g prior to force measurement. The isotonic contractions of longitudinal muscle were recorded for 1 hour, with H-T buffer being changed every 15 minutes. The mean amplitude of the basal tension and frequency of phasic contractions were measured for 30 minutes after experiments. The detailed force assays were performed according to our previously described methods54, 55.

Short chain fatty acid and bile acid determination in the cecum

The caecal contents from mice were collected, freeze-dried, and pulverized. Feces samples (150 mg) were homogenized and centrifuged in 1000 μL of 0.005 M aqueous NaOH that contained an internal standard (5 μg/mL caproic acid-d3). Next, SCFAs (acetate, propionate and butyrate) were quantified as in our previous study by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis56. The Agilent 7890A gas chromatography system coupled to an Agilent 5975 C inert XL EI/CI mass spectrometric detector (MSD; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used to analyze the SCFA concentrations. BAs were quantified using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) as described previously57. Fecal samples (200 mg) were used for the BA determination (CA, CDCA, DCA and LCA). BA stock solutions were diluted with 50% methanol and spiked with internal standards to construct standard curves. The LC-MS/MS system consisted of an API 4000 QTrap (AB Sciex, Darmstadt, Germany) coupled to electrospray ionization. Chromatographic separation was achieved using an Agilent 1200 HPLC system (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany). Each SCFA and BA was identified by their relative retention time compared with that of standard SCFAs and BAs, respectively.

Microbiota analyses

Stool samples (500 mg) from mice or humans were collected in sterile tubes and were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored in a −80 °C freezer until processing for DNA isolation. The microbiota were analyzed using 16S rRNA pyrosequencing technology at the BGI laboratory (Beijing Genomic Institute, Shenzhen, China) as previously described56. Total DNA was isolated using a Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, USA). After DNA isolation, concentration testing and sample integrity were performed for sample analyses. A fluorometer or microplate reader was used to detect the concentration, and 1% agarose gel electrophoresis (voltage, 150 V; electrophoresis time, 40 minutes) was used to detect the sample integrity. Primers were designed to amplify the V4 hypervariable region according to the manufacturer’s recommendations58. Genomic DNA was normalized to 30 ng per polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the library using the V4 Dual-index Fusion PCR Primer Cocktail and PCR Master Mix (NEB Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix; NEB, Ipswich, MA). The library validation was quantified through real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) (EvaGreen; Biotium, Fremont, CA). The qualified libraries were sequenced pair end on the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA) using the sequencing strategy PE250 (MiSeq Reagent Kit; Illumina). Bioinformatics analysis was performed as previously described56, 59. The MOTHUR v.1.27.0 Standard Operation Procedure (SOP) and QIIME pipeline were used to analyze high-quality sequence reads.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism V.6.0 (San Diego, CA, USA) was used for all analyses and preparation of graphs. Continuous data were presented as the means ± SEM or median (range), while the categorical data were presented as n (%). Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test was used to analyze continuous variables depending on the normality of the data distribution. Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables as appropriate. Significant differences identified using the above tests were indicated in figures as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos 81670493, and 81270006) and the National Gastroenterology Research Project (2015BAI13B07). The authors thank Yichang Liu from Cornell University and Claire Liu from Australian National University for checking grammar and typographical errors of the entire manuscript.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: N.L., M.S. and J.G. Performed the experiments: X.G., W.Z., C.D., L.X., H.T., H.W., N.L., J.J. and W.Z. Data analyzed: X.G., W.Z. and J.G. Manuscripts drafting: X.G. and W.Z. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript prior to its submission.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Xiaolong Ge and Wei Zhao contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jianfeng Gong, Email: jinlingh_gongjf@163.com.

Weiming Zhu, Email: njuzms@126.com.

Ning Li, Email: jinlingh_lining@163.com.

References

- 1.Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;349:1360–1368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mearin, F. et al. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology, doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bharucha AE, Pemberton JH, Locke GR., 3rd American Gastroenterological Association technical review on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:218–238. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He CL, et al. Decreased interstitial cell of cajal volume in patients with slow-transit constipation. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:14–21. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wedel T, et al. Enteric nerves and interstitial cells of Cajal are altered in patients with slow-transit constipation and megacolon. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1459–1467. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Salhy M, Norrgard O, Spinnell S. Abnormal colonic endocrine cells in patients with chronic idiopathic slow-transit constipation. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 1999;34:1007–1011. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shekhar, C. et al. Rome III functional constipation and irritable bowel syndrome with constipation are similar disorders within a spectrum of sensitization, regulated by serotonin. Gastroenterology145, 749–757, quiz e713–744, 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.014 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Boeckxstaens, G. et al. Fundamentals of Neurogastroenterology: Physiology/Motility - Sensation. Gastroenterology, doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.030 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Obata, Y. & Pachnis, V. The Effect of Microbiota and the Immune System on the Development and Organization of the Enteric Nervous System. Gastroenterology, doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.07.044 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Barbara, G. et al. The Intestinal Microenvironment and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterology, doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.028 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Zhao Y, Yu YB. Intestinal microbiota and chronic constipation. SpringerPlus. 2016;5:1130. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2821-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu L, et al. Structural changes in the gut microbiome of constipated patients. Physiological genomics. 2014;46:679–686. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00082.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khalif IL, Quigley EM, Konovitch EA, Maximova ID. Alterations in the colonic flora and intestinal permeability and evidence of immune activation in chronic constipation. Digestive and liver disease: official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2005;37:838–849. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi CH, Chang SK. Alteration of gut microbiota and efficacy of probiotics in functional constipation. Journal of neurogastroenterology and motility. 2015;21:4–7. doi: 10.5056/jnm14142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parthasarathy, G. et al. Relationship Between Microbiota of the Colonic Mucosa vs Feces and Symptoms, Colonic Transit, and Methane Production in Female Patients With Chronic Constipation. Gastroenterology150, 367–379 e361, doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.005 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Vandeputte D, et al. Stool consistency is strongly associated with gut microbiota richness and composition, enterotypes and bacterial growth rates. Gut. 2016;65:57–62. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahakian AB, Jee SR, Pimentel M. Methane and the gastrointestinal tract. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2135–2143. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian, H. et al. Treatment of Slow Transit Constipation With Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: A Pilot Study. Journal of clinical gastroenterology, doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000472 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Quigley EM, Spiller RC. Constipation and the Microbiome: Lumen Versus Mucosa! Gastroenterology. 2016;150:300–303. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherbut C, et al. Short-chain fatty acids modify colonic motility through nerves and polypeptide YY release in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G1415–1422. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.6.G1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukumoto S, et al. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate colonic transit via intraluminal 5-HT release in rats. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2003;284:R1269–1276. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00442.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bunnett NW. Neuro-humoral signalling by bile acids and the TGR5 receptor in the gastrointestinal tract. The Journal of physiology. 2014;592:2943–2950. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.271155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yano JM, et al. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell. 2015;161:264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu L, Yu BP, Chen JG, Luo HS. Mechanisms mediating serotonin-induced contraction of colonic myocytes. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology. 2007;34:120–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alemi F, et al. The receptor TGR5 mediates the prokinetic actions of intestinal bile acids and is required for normal defecation in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:145–154. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cherbut C, Aube AC, Blottiere HM, Galmiche JP. Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Gastrointestinal Motility. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 1997;32(Suppl 222):58–61. doi: 10.1080/00365521.1997.11720720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernandez-Chirlaque, C. et al. Germ-free and Antibiotic-treated Mice are Highly Susceptible to Epithelial Injury in DSS Colitis. Journal of Crohn’s & colitis, doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw096 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Hintze KJ, et al. Broad scope method for creating humanized animal models for animal health and disease research through antibiotic treatment and human fecal transfer. Gut microbes. 2014;5:183–191. doi: 10.4161/gmic.28403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soret R, et al. Short-chain fatty acids regulate the enteric neurons and control gastrointestinal motility in rats. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1772–1782. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wahlstrom A, Sayin SI, Marschall HU, Backhed F. Intestinal Crosstalk between Bile Acids and Microbiota and Its Impact on Host Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;24:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barbara G, et al. Interactions between commensal bacteria and gut sensorimotor function in health and disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2560–2568. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hooper LV, et al. Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science. 2001;291:881–884. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5505.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Husebye E, Hellstrom PM, Sundler F, Chen J, Midtvedt T. Influence of microbial species on small intestinal myoelectric activity and transit in germ-free rats. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2001;280:G368–380. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.3.G368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadizadeh, F. et al. Stool frequency is associated with gut microbiota composition. Gut, doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311935 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Backhed F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell. 2016;165:1332–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larraufie, P., Dore, J., Lapaque, N. & Blottiere, H. M. TLR ligands and butyrate increase Pyy expression through two distinct but inter-regulated pathways. Cellular microbiology, doi:10.1111/cmi.12648 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Appleby RN, Walters JR. The role of bile acids in functional GI disorders. Neurogastroenterology and motility: the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2014;26:1057–1069. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peregrin AT, Ahlman H, Jodal M, Lundgren O. Involvement of serotonin and calcium channels in the intestinal fluid secretion evoked by bile salt and cholera toxin. British journal of pharmacology. 1999;127:887–894. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kidd M, et al. Luminal regulation of normal and neoplastic human EC cell serotonin release is mediated by bile salts, amines, tastants, and olfactants. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2008;295:G260–272. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00056.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sayin SI, et al. Gut microbiota regulates bile acid metabolism by reducing the levels of tauro-beta-muricholic acid, a naturally occurring FXR antagonist. Cell Metab. 2013;17:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dey N, et al. Regulators of gut motility revealed by a gnotobiotic model of diet-microbiome interactions related to travel. Cell. 2015;163:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ridlon JM, Bajaj JS. The human gut sterolbiome: bile acid-microbiome endocrine aspects and therapeutics. Acta pharmaceutica Sinica. B. 2015;5:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weingarden AR, et al. Microbiota transplantation restores normal fecal bile acid composition in recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2014;306:G310–319. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00282.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Angelberger S, et al. Temporal bacterial community dynamics vary among ulcerative colitis patients after fecal microbiota transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1620–1630. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tian H, et al. Freeze-dried, Capsulized Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Relapsing Clostridium difficile Infection. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2015;49:537–538. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wei Y, et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Improves the Quality of Life in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology research and practice. 2015;2015:517597. doi: 10.1155/2015/517597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seki E, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nature medicine. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Natividad JM, et al. Ecobiotherapy Rich in Firmicutes Decreases Susceptibility to Colitis in a Humanized Gnotobiotic Mouse Model. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2015;21:1883–1893. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turnbaugh PJ, et al. The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: a metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Science translational medicine. 2009;1:6ra14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, T. et al. Sodium Butyrate Reduces Colitogenic Immunoglobulin A-Coated Bacteria and Modifies the Composition of Microbiota in IL-10 Deficient Mice. Nutrients8, doi:10.3390/nu8120728 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Baptissart M, et al. Bile acids alter male fertility through G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 signaling pathways in mice. Hepatology. 2014;60:1054–1065. doi: 10.1002/hep.27204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nezami BG, et al. MicroRNA 375 mediates palmitate-induced enteric neuronal damage and high-fat diet-induced delayed intestinal transit in mice. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:473–483. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He WQ, et al. Myosin light chain kinase is central to smooth muscle contraction and required for gastrointestinal motility in mice. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:610–620. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He WQ, et al. Altered contractile phenotypes of intestinal smooth muscle in mice deficient in myosin phosphatase target subunit 1. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1456–1465. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang, J. et al. Soluble Dietary Fiber Ameliorates Radiation-Induced Intestinal Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Fibrosis. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition, doi:10.1177/0148607116671101 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Schmid A, Neumann H, Karrasch T, Liebisch G, Schaffler A. Bile Acid Metabolome after an Oral Lipid Tolerance Test by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) PloS One. 2016;11:e0148869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arumugam M, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu H, et al. Plaque bacterial microbiome diversity in children younger than 30 months with or without caries prior to eruption of second primary molars. PloS One. 2014;9:e89269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]