Abstract

Truant youth are likely to engage in a number of problem behaviors, including sexual risky behaviors. Previous research involving non-truant youth has found sexual risk behaviors to be related to marijuana use and depression, with differential effects for male and female youth. Using data collected in a NIDA funded, prospective intervention project, results are reported of a male-female, multi-group, longitudinal analysis of the relationships among truant youth baseline sexual risk behavior, marijuana use, and depression, and their sexual risk behavior over four follow-up time points. Results indicated support for the longitudinal model, with female truants having higher depression scores, and showing stronger relationships between baseline depression and future engagement in sexual risk behavior, than male truants. Findings suggest that incorporating strategies to reduce depression and marijuana use may decrease youth sexual risk behavior.

Keywords: sexual risk, truants, truancy, marijuana use, depression, STD

Introduction

Adolescents and young adults have high rates of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). According to the CDC’s STD prevalence estimates, “young people aged 15–24 years acquire half of all new STDs and that 1 in 4 sexually active adolescent females have an STD…” (CDC, 2014, p. 58). The prevalence rates for chlamydia and gonorrhea are highest for the 15–19 and 20–24 age groups, with the rates being higher among females than males (CDC, 2014). Youth with STDs are at elevated risk for acquiring HIV, and youth (ages 13–24) account for a disproportionate amount of new HIV infections, 26% of new HIV cases in 2010 (CDC, 2012). High-risk youth, such as those having contact with the justice system, are at particularly high risk of being or becoming STD positive (e.g., Hendershot, Magnan, & Bryan, 2010; Schmiege, Levin, Broaddus, & Bryan, 2009; Teplin, Mericle, McClelland, & Abram, 2003). Although a number of factors have been identified as being associated with STD risk (e.g., Voisin, Hong, & King, 2012), the present paper focuses on the association among risky sexual behavior, marijuana use, and depression.

Marijuana Use and Sexual Risk Behavior

Adolescents are at increased risk of using illicit substances such as marijuana. The Monitoring the Future survey conducted longitudinal research on prevalence and frequency of illicit substance use over the last forty years and indicates the most prevalent illicit substance used among adolescents in the U.S. is marijuana (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2014). Marijuana prevalence peaked in the late 1970’s at 51%, dropped markedly during the 1980’s, peaked again to around 40% in late 1990’s, declined slightly during the early 2000’s, and recently increased slightly in the 2010’s (Johnston et al., 2014). Marijuana use has been associated with a variety of negative life events, poor health, and antisocial behaviors (e.g., Grigorenko, Edwards, & Chapman, 2015; Meier et al., 2012).

Marijuana use is also associated with risky sexual behaviors, such as sex with unknown others, early sex, receiving money for sex, and lack of condom usage (Hendershot et al., 2010; Wu, Witkiewitz, McMahon, Dodge, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2010). For example, Huang, Murphy, and Hser (2012) examined a nationally representative sample of youths to identify trajectories of sexual risk behaviors over time. They found five distinct trajectories of sexual risk in their sample, and marijuana use was significantly and positively correlated with sexual risk at each age (wave of data) and growth in sexual risk over time. Further, marijuana use is positively associated with risk of STDs and HIV (e.g., Hendershot et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2010).

Depression and Sexual Risk Behavior

Generally, sexual risk behaviors and STD infection are associated with depressive symptoms among adolescents (e.g., Shrier, Harris, Sternberg, & Beardslee, 2001). For example, in a study using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, Hallfors and associates (2004) used cluster analysis to identify sixteen subgroups of youth based on substance use and sexual risk behavior. Differences in depression and suicidal ideation were then examined across the subgroups. Results indicated involvement in sexual activity heightened the risk of reporting major depression symptoms. Although girls were less likely to be involved in risk behavior, those who were involved experienced more depression. Research involving justice-involve youth have obtained similar relationships between depression and involvement in sexual risk behavior (e.g., Teplin et al., 2005). Some studies on the link between sexual risk and depression, however, have indicated null findings (e.g., Chen, Stiffman, Cheng, & Dore, 1997).

Further, the direction of the association between sexual risk behaviors and depressive symptoms remains unclear. For instance, subsequent analyses using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health data by Hallfors and associates indicated that engaging in sexual risky behavior and drug use increased the likelihood of future depression among adolescents, especially girls, but depression did not predict risky sexual and drug behaviors (Hallfors, Waller, Bauer, Ford, & Halpern, 2005). In an earlier study using the same data source, however, Shrier et al. (2001) reported depressive symptoms predicted sexual risk behaviors (lack of condom use) and STD infection among boys, but not among girls (see also, Lehrer, Shrier, Gortmaker, & Buka, 2006; Shrier, Harris, & Beardslee, 2002). More research is needed to clarify the association between sexual risk behavior and depression.

Marijuana Use and Depression

Research has also linked marijuana use with mental health problems (e.g., Bovasso, 2001; Chen, Wagner, & Anthony, 2002; McGee, Williams, Poulton, & Moffitt, 2000). For example, in a longitudinal study of adolescents, Horwood et al. (2012) found increased frequency of marijuana use was related to more symptoms of anxiety and depression, with the association declining in adulthood. Patton et al. (2002) also examined longitudinal data on marijuana and mental health problems from adolescence into adulthood. Their results indicated the prevalence of depression and anxiety increased with increased usage of marijuana, with the effects being most clear for female participants. Females using cannabis daily had a five-fold greater increase in the odds of experiencing anxiety and depression over non-users of the drug. Studies of justice-involved youth have also revealed comorbidity in marijuana use and depression (e.g., Abram, Teplin, McClelland, & Dulcan, 2003; Stein et al., 2011).

Focus on Truant Youth in Present Study

Relatively little is known about the connection between marijuana use, depression, and sexual risk behavior among truant adolescents. Truancy refers to unauthorized, intentional absence from compulsory school, and is a serious issue that affects most school districts in the U.S. (National Center for School Engagement, 2006). It has been identified as a precursor for more serious negative and antisocial behaviors (Garry, 2001), including involvement in the justice system. In particular, truancy is associated with an assortment of negative indicators, such as high school dropout (e.g., Bridgeland, Dilulio, & Morison, 2006), family problems (e.g., Baker, Sigmon, & Nugent, 2001), mental health problems (e.g., Dembo et al., 2012), substance use and abuse (e.g., Henry, Thornberry, & Huizinga, 2009), and juvenile delinquency and crime (e.g., Garry, 2001; Loeber & Farrington, 2000). Truancy has also been associated with risky sexual behaviors (e.g., Eaton, Brener, & Kann, 2008). Given the numerous risk factors associated with truancy and scant research on this population, truant youth represent an important group meriting greater attention in research.

The present study explored the relationship between marijuana use, depression, and sexual risk behaviors among truant adolescents using data from a sample of truant youth who participated in a NIDA-funded, experimental, prospective intervention in a southeastern U.S. state. Much has been published about this particular sample of truant youth over the years. Germane to the present study of these youth, previous analyses have revealed differential effects of mental health problems (Dembo, Wareham, Schmeidler, Briones-Robinson, & Winters, 2014), substantial co-morbidity of problem behaviors among the youth (Dembo, Briones-Robinson, et al., 2012; Dembo, Wareham, Schmeidler, & Winters, in press), and trends in sexual risk behaviors over time for the total sample that are associated with trends in substance use over time (Dembo, Briones-Robinson, Barrett, et al., 2014; Dembo, Briones-Robinson, Ungaro et al., 2014; Dembo, Briones-Robinson, Wareham, et al., 2016). More recently, latent class analyses revealed gender differences in the association between sexual risk behaviors and depression symptoms (Dembo, Wareham, Krupa, & Winters, in press). To date, however, none of the analyses using this sample have examined the simultaneous association between marijuana use, depression symptoms, and sexual risk behaviors on sexual risk over time and gender differences.

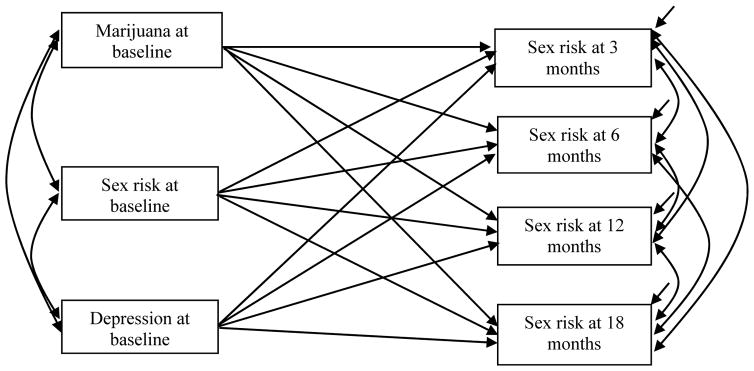

It was hypothesized there would be a contemporaneous association among marijuana, depression symptoms, and sexual risk behaviors at baseline, which would be associated with sexual risk behavior over time. Figure 1 illustrates the longitudinal model used to test this hypothesis. The truant youths’ baseline marijuana use, sexual risk behavior, and depression measure were specified as co-varying indicators. Each of these baseline variables was specified to predict youths’ sexual risk behavior at each of four follow-up time points. In addition, each follow-up sexual risk behavior measure was correlated with earlier measures. Finally, consistent with research indicating gender group differences in prevalence, correlates, and consequences of sexual risk behavior, it was hypothesized there would be gender differences in the model. Therefore, a cross-gender, multi-group estimation of the model was performed. Following a discussion of the method and results, service and practice implications are discussed.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Model: Sexual Risk, Depression, and Marijuana Use at Baseline Effects on Sexual Risk Behavior at Each Follow-up Time Point.

Method

Procedures

Procedures for this study were approved and monitored for ethics by the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Participants were involved in a Brief Intervention (BI) project for truant youth involved in substance use. They were recruited for the project primarily from the local truancy center, but also local school guidance counselors and a community diversion program. The truancy center is a school-based center that provides a classroom-like setting for youths who have been apprehended by local law enforcement for truancy during school hours.

Project staff informed recruited youths and their parents/guardians of the purpose of the study, specified participation was free and voluntary, and indicated services would be delivered in-home. Following consent and assent procedures and completion of retrospective youth and parent baseline interviews, participants were randomly assigned, with balanced distribution, to one of three project service conditions: BI-youth only (BI-Y), BI-youth plus an additional parent individual session (BI-YP), or standard truancy services (STS). The study was prospective in that it followed the youth from the time of enrollment as they progressed through school, the truancy program, and the intervention (BI-Y vs. BI-YP), and collected drug use, delinquency, and other factors over potentially 18-months of follow-up. The follow-up period began the day after the date of the youth’s last participation in project services (i.e., the last intervention or STS session). Follow-up interviews were conducted at 3-months, 6-months, 12-months, and 18-months. Each youth and his/her parent/guardian was paid $15 for completing each in-home, baseline and follow-up interview. Youth interviews took approximately 60 minutes to complete, while parent interviews took 30 minutes.

Participants

To enroll in the project, truant youths had to meet the following criteria: 11 to 17 years of age at time of enrollment; reside within 25 miles of truancy center; possess two or fewer misdemeanor arrests on criminal record; demonstrate involvement in alcohol or drug use, as determined by a screening instrument or reported by a school or truancy center social worker. The final sample consisted of 300 youths who were enrolled and completed baseline interviews between March 2007 and June 2012. Depending on the enrollment date, follow-up interviews were also administered at 3-month (n = 282), 6-month (n = 281), 12-month (n = 245), and 18-month (n = 215) follow-up. Not all youth in the study were eligible to receive all four follow-up interviews. Since enrollment for the study spanned five years wherein youth were enrolled as they were identified in the school district as truant and meeting the aforementioned criteria, youth who enrolled at the beginning of the project were available for all four waves of follow-up interviews (i.e., 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month), whereas youth who enrolled toward the end of the enrollment phase were available for fewer to none of the follow-up interviews. Adjusting for eligibility based on enrollment date, completion rates of 94.0%, 93.7%, 92.1%, and 88.5% were achieved for the 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month follow-up interviews, respectively, with over 95% in each follow-up period completed within 60 days of the scheduled interview date.

Intervention Conditions

Although the present study did not test the efficacy of the BI on truant youth, it was important to control for the effects of treatment. The goal of the BI was to promote abstinence and prevent relapse among drug-using adolescents. Adapted from previous work, the BI incorporated elements of Motivational Interviewing, Rational-Emotive Therapy and Problem-Solving Therapy to develop adaptive beliefs and problem-solving skills to improve positive coping mechanisms (Winters & Leitten, 2007) via problem-solving skills and support from the environment (Winters, Lee, Botzet, Fahnhorst, & Nicholson, 2014). Youths assigned to the BI-Y condition were administered two BI sessions, without a parent session; while those assigned to the BI-YP condition were administered two BI sessions and their parents were administered a separate parent BI session.

Youths randomly assigned to the STS condition received the normal truancy services provided by the local school district, as well as a referral service overlay of three weekly, 60-minute visits by project staff. For the referral service overlay, research staff provided participating families, upon request, with referral information contained in a comprehensive county government-developed agency and service resource guide. No form of counseling or therapy was offered in the STS condition.

Measures

Socio-demographic characteristics

The baseline interviews with the adolescents and their parents provided several socio-demographic indicators. Youth were asked to indicate their age in number of years and gender (coded 0 = male; 1 = female). Youth were also asked to indicate their race/ethnicity, which included a category for Hispanic origin. The race/ethnicity indicator was dummy coded such that race was coded 1 = African American, non-Hispanic and 0 = other race, non-Hispanic, and ethnicity was coded 1 = Hispanic of any race and0 = non-Hispanic. Relatively few youths lived with both biological parents at the time of the baseline interview. Hence, youth lives with mother was a dichotomous variable reflecting whether (1) or not (0) the youth lived with their biological mother. During the baseline interview, parents were asked to provide information about their annual family income. Family income was an ordinal variable where 1 = less than $5,000, 2 = $5,001 to $10,000, 3 = $10,001 to $25,000, 4 = $25,001 to $40,000, 5 = $40,001 to $75,000, and 6 = more than $75,000. Parents were also asked at baseline to indicate whether or not the youth or their family ever experienced certain serious stressful or traumatic events. Negative life events or family trauma, such as family death, parental divorce, and hospitalization have been associated with problems such as depression among sexual risk adolescent populations (e.g., Lewis, Abramowitz, Koenig, Chandwani, & Orban, 2015) and problem behaviors among youth in general (e.g., Agnew & White, 1992). Generally negative life events are measured as a cumulative index of the number of events that have happened within the person’s family, though some scholars suggest it may be important to compare objective versus subjective strains (Agnew, 2001). In the present study, parents were questioned about the following events: accidental injury requiring hospitalization, serious illness, death, divorce, eviction, unemployment of a parent, legal problems resulting in jail or detention, victimization of violence, and any other (unspecified) traumatic event. A summary index was created for affirmative responses (1 = yes, 0 = no) to the nine items, such that higher scores indicate experience of multiple traumatic events.

Depression

A depression at baseline variable was created from responses to the Adolescent Diagnostic Interview (ADI) (Winters & Henly, 1993). The ADI was designed to be delivered within a highly structured and standardized format (e.g., most questions are yes/no) to capture DSM-IV criteria for substance use disorders and related areas of functioning. For each item in the ADI, youth not reporting the experience were coded as 0, those reporting the experience were coded as 1. The ADI has demonstrated strong reliability and validity (Winters & Henly, 1993; Winters & Stinchfield, 2003). While the ADI does not identify clinical levels of psychiatric problems, it does identify psychiatric symptoms based on clinical, or DSM, symptomology. The ADI has been previously used as a measure of psychiatric symptoms, including depression, and substance use problems among adolescents (Shrier, Harris, Kurland, & Knight, 2003). A measure of psychiatric symptoms of depression (henceforth referred to as depression) was created from five items in the ADI. The depression measure was created using exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses employing maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian estimation procedures.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the five depression items indicated they were significantly loaded on one factor. However, the distribution of these data did not meet the asymptotic distribution assumptions of ML, with a resulting poor model fit. On the other hand, Bayesian estimation confirmed the existence of a one-factor model, with a good fit of the model to the data. Based on these results, the factor scores for a one-factor model of depression were saved and used as the depression index in subsequent analyses. Higher scores indicate higher problems with depression.

Marijuana use

Marijuana use at baseline was measured through self-report questions on the ADI and urine assay tests (UA). The self-report questions probed ever using marijuana as: never, less than five times, or five or more times. Urine specimens for drug use were collected with the Onsite CupKit® urine screen procedure, where marijuana (THC) positive tests thresholds were 50 ng/ml of urine and surveillance windows were 5 days for moderate use, 10 days for heavy use, and 30 days for chronic use.

The self-report and urine test results for marijuana were combined to create an ordinal measure of marijuana use at baseline. Marijuana use was coded into four categories: (1) marijuana use denied and UA negative (7%), missing due to reasons beyond the youth’s control [e.g., incarcerated] (0.3%), or missing not due to reasons beyond the youth’s control [e.g., participant refusal] (0.3%); (2) self-reported use one to four times, but UA missing or negative (17%); (3) self-reported use five or more times, but UA test missing or negative (29%); and (4) UA positive (46%; 98% with self-reported use).

Sexual risk behavior

Measures of sexual risk behavior at baseline and at each follow-up interview were created using data collected from the youths with the POSIT HIV/STD Risk Behavior instrument. The POSIT 11-item HIV/STD risk scale was developed by the NOVA Research Company (Young & Rahdert, 2000), and has demonstrated very good psychometric properties (e.g., internal consistency = 0.80, one-week test-retest reliability = 0.90; concurrent validity with the Sexual Risk Questionnaire scores: r = 0.80). In the current study, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of the 11 items was 0.73.

Lack of condom use and number of sexual partners, in particular, are widely used sexual risk behavior measures (e.g,, Komro, Tobler, Maldonado-Molina, & Perry, 2010). This study developed a summary measure of youths’ involvement in four of the sexual risk behaviors at each time point: (1) had sexual intercourse, (2) had sexual intercourse without using a condom, (3) had sex with two or more people, and (4) had a sexually transmitted disease. Low endorsement rates for the STD item at each time point led to the recoding of the sexual risk summary measure to include youths reporting all four sexual risk behaviors in the fourth category of the final ordinal measure used in analyses, together with youths reporting three risk behaviors.

Data Analysis

The analyses proceeded in several stages. First, differences across gender were examined for the variables and bivariate relationships between the variables in the hypothesized model (Figure 1) were examined separately for girls and boys. Next, a multi-group analysis of the fit of the data to the model across the female and male youth groups was estimated. Since the tested model was just identified, another analysis was conducted to obtain model fit information. Finally, separate analyses for the female and male youths were estimated, studying the relationship of the socio-demographic covariates with baseline measures of sexual risk behavior, marijuana use, and depression. The analyses were completed using Mplus Version 7.3 (Muthèn & Muthèn, 1998–2012). Because the time of entry into the study determined the number of follow-up interviews received, missing data are a consequence of the study design. Accordingly, the Mplus feature allowing for ML estimation of missing values was used to treat the missing data (Muthèn & Muthèn, 1998–2012).

Since sexual risk behavior at each time point was measured by an ordinal (polytomous) variable, a robust weighted least square estimator, using a diagonal weight matrix, with mean-adjusted and variance-adjusted chi-square test statistics (WLSMV) was used in these analyses (Muthèn & Muthèn, 1998–2012). A non-significant chi-square value for WLSMV indicates acceptable model fit. Three fit indices were used to evaluate the model fit: comparative fit index (CFI: Bentler, 1990); Tucker-Lewis index (TLI: Tucker & Lewis, 1973); and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA: Byrne, 2001).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Comparisons across Gender for Variables

Most of the youth were male (63%). The youth averaged 14.8 (SD = 1.30) years in age at baseline, and were racially and ethnically diverse. Overall, 26% of the youth were African American and 29% Hispanic, regardless of race (Anglo/Caucasian, non-Hispanic = 29%; Asian, non-Hispanic = 2%; other race, non-Hispanic = 10%). Relatively few youths were living with both biological parents at the time of baseline interview, and approximately one-third of them were living with their birth mother alone. Overall, the families in the study reported modest family incomes. Many of the families reported experiencing one or more stressful or traumatic events at baseline. On average, families reported 2.99 (SD = 1.76) traumatic events at the time of the baseline interview. There were no significant differences in age, living situation, family income, and family experiences of traumatic events across gender. There were significant differences across gender in race/ethnicity (Fisher’s Exact Test = 26.35, p < .001), such that male youths were more likely to be African American and female youths were more likely to be Anglo.

As shown in Table 1, many of the youths reported affirmative responses to the five symptoms of depression in the baseline interview such as feeling sad for extended periods of time and difficulty with sleep, and some of the youths also reported problems related to suicidal thoughts. The depression index scores were higher among girls than boys. Indeed, further analysis found a significant difference in the mean depression index for the male and female youth in the study.

Table 1.

Distribution of Depression Items and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results of Depression Index, Including Comparison across Gender (n=300)

| Depression Items | Percentage “Yes” | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Has there ever been a continuous 2 week time period during which you felt sad or down most of the time-as if you didn’t care anymore about anything? | 56% | ||||||

| 2. Have you ever continuously felt like crying for several days in a row? | 36% | ||||||

| 3. Have you ever had any trouble sleeping that lasted for many days? | 43% | ||||||

| 4. Have you ever felt so down that you felt like ending your life? | 24% | ||||||

| 5. Have you ever actually attempted suicide? | 8% | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Depression Index Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: | |||||||

| Maximum Likelihood Estimation | Bayesian Estimation | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Chi-Square | df | p-value | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | PSR | PPP |

| 30.481 | 5 | 0.000 | 0.961 | 0.922 | 0.130 | 1.006 | 0.333 |

|

| |||||||

| Comparison across Gender for Depression Index | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Male (n = 189) | Female (n | =111) | Significance | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Mean Depression Factor Scores (SD) | −0.42 (1.20) | 0.65 (1.36) | F(1,298) = 49.30, p < .001 | ||||

Note. CFI = comparative fit index. TLI = Tucker-Lewis index. RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation. PSR = potential scale reduction factor. PPP = posterior productive p-value.

A majority of youths in the study self-reported or tested positive for some level of marijuana use: denied use and urine test negative or missing (females = 9%; males 7%); reported use 1–4 times and urine test negative or missing (females = 19%; males 16%); reported use 5 or more times and urine test negative or missing (females = 30%; males 29%); or urine test positive (females = 42%; males 48%). This is not surprising given the fact that the data come from a clinical trial of drug-involved truant youth. A very small portion of youths reported no use or tested negatively for marijuana. Since the youths were enrolled for a variety of substance uses including alcohol, this result is also not surprising. The present study, however, explores the impact of the magnitude of use in marijuana on sexual risk behaviors. No significant difference was found between the male and female youths in their baseline marijuana use.

Table 2 shows the percent of youths replying affirmatively to each sexual risk behavior item at each time point. Overall, at baseline, 67% of the youths reported they had sexual intercourse. Importantly, sizable percentages of youths indicated they had sexual intercourse without using a condom (33%), and having two or more sexual partners (30%). In addition, 3% of the youths reported they ever had a sexually transmitted disease. Comparison of these results with findings reported in the Centers of Disease Control, 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance ([YRBS] CDC, 2011), indicated a much higher rate of ever having had sexual intercourse among youths in the present study, than that reported by youths in the YRBS nationally (47%) or in Florida (overall: 48%; 9th grade: 31%; 10th grade: 45%; 11th grade: 57%). This result is consistent with the expectation that truant youth engage in sexual risk behavior at a higher rate than the general youth population. Results in Table 2 also show the overall rates of reported involvement in the sexual risk behaviors were consistent over time. (Although sizable percentages of youth did not report engaging in one or more of the sexual risk behaviors during the intervals reported on in Table 2, it is important to note that the vast majority of youth reported ever having had some sexual experience [e.g., sexual contact with another person] at each time point [baseline, 80%; 3-month follow-up, 72%; 6-month follow-up, 72%; 12-month follow-up, 76%; 18-month follow-up, 75%]).

Table 2.

Sexual Risk Behaviors at Baseline and Follow-Up, Including Comparison across Gender

| Follow-up period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Baseline (%) | 3-Month (%) | 6-Month (%) | 12-Month (%) | 18-Month (%) |

| Sexual risk behaviors: | |||||

| Sexual intercourse | 67.0 | 62.4 | 61.9 | 62.8 | 63.4 |

| Sexual intercourse without using a condom | 33.3 | 28.4 | 31.7 | 33.5 | 36.2 |

| Sex with two or more people | 29.7 | 32.3 | 33.6 | 33.8 | 33.7 |

| Sexually transmitted disease (STD) | 2.7 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 3.7 |

| Total number of sexual risk behaviors reported: | Male/Female | Male/Female | Male/Female | Male/Female | Male/Female |

| 0 | 31/34 | 36/39 | 36/38 | 35/22 | 28/21 |

| 1 | 26/19 | 19/19 | 17/22 | 20/25 | 19/19 |

| 2 | 24/24 | 28/26 | 25/25 | 22/34 | 27/35 |

| 3 or 4 | 18/23 | 17/16 | 22/15 | 23/19 | 26/25 |

| n | 189/111 | 177/105 | 177/104 | 157/88 | 139/76 |

| Significance: | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. |

Note. N.S. = non-significant difference across gender.

In addition, descriptive results are presented in Table 2 on the summary index of sexual risk behavior across the five time points by gender. There is gradual, non-patterned increase in the percent of male and female youth reporting engagement in the sexual risk behaviors from 3-month to 18-month follow-up, and a corresponding general decrease in the percent of youths reporting not engaging in any of these behaviors. There were no significant differences between male and female youth in the reported numbers of sexual risk behaviors at each time point.

Correlations among Variables in the Model for Female and Male Youth

As shown in Table 3, there were significant correlations between 36 of the 42 (86%) pairs of variables in the hypothesized model. Depression had higher magnitudes of associations with other variables in the model among females than males, with more significant associations despite the smaller sample sizes. Although marijuana was more often significantly related to sexual risk behaviors among males than females, this partly reflected the larger sample sizes for males.

Table 3.

Correlations among Depression, Marijuana Use, and Sexual Risk Behavior for Males (below diagonal) and Females (above diagonal)

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depression at baseline | -- | .300* | −.087 | .298* | .196* | .410* | .262* |

| 2. Sexual risk at baseline | .176* | -- | .386* | .694* | .575* | .639* | .432* |

| 3. Marijuana at baseline | −.087 | .266* | -- | .389* | .364* | .189 | .263* |

| 4. Sexual risk at 3-months | .165* | .701* | .364* | -- | .753* | .705* | .622* |

| 5. Sexual risk at 6-months | .104 | .683* | .260* | .718* | -- | .603* | .685* |

| 6. Sexual risk at 12-months | .134 | .636* | .237* | .647* | .646* | -- | .775* |

| 7. Sexual risk at 18-months | .130 | .658* | .234* | .570* | .678* | .755* | -- |

Note. 3-months, 6-months, 12-months, and 18-months refer to the follow-up period after completion of intervention or standard services. Two-tailed p-values:

p < .05

Results of the Just Identified Model

The results of the multi-group (gender) fit of the model to the data are presented in Table 4. As can be seen, significant relationships existed between sexual risk behavior, depression, and marijuana use at baseline for females and males. Sexual risk behavior measured at baseline was significantly related to involvement in sexual risk behavior at each follow-up time point for both gender groups. Among male youths, marijuana use was significantly related to sexual risk behavior at 3-month follow-up, and marginally, significantly related to sexual risk behavior at 6-month follow-up. Among female youths, marijuana use was significantly related to sexual risk behavior at 3-month follow-up and 6-month follow-up, and marginally, significantly related to sexual risk behavior at 18-month follow-up. Further, among male youths, depression measured at baseline was not significantly related to involvement in sexual risk behavior at any follow-up time point. In contrast, among female youths, depression at baseline was significantly related to sexual risk behavior at 3-month follow-up and 12-month follow-up, and marginally, significantly related to this behavior at 18-month follow-up. Overall, these results provide sizable support for the conceptual model, and reflect an important gender group difference in the influence of depression on involvement in sexual risk behavior over time.1

Table 4.

Results of Model of Sexual Risk Behavior, Marijuana Use, and Depression at Baseline on Sexual Risk Behavior Over Time among Male (n = 189) and Female (n = 111) Youth (WLSMV Estimation)

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Critical Ratio | Estimate | SE | Critical Ratio | |

| Sex risk, 3-mon. ON: | ||||||

| Sex risk, baseline | 0.524 | 0.057 | 9.166*** | 0.444 | 0.069 | 6.426** |

| Marijuana, baseline | 0.245 | 0.070 | 3.476*** | 0.204 | 0.104 | 1.969* |

| Depression, baseline | 0.074 | 0.053 | 1.394 | 0.126 | 0.063 | 2.011* |

| Sex risk, 6-mon. ON: | ||||||

| Sex risk, baseline | 0.539 | 0.050 | 10.686*** | 0.384 | 0.080 | 4.822*** |

| Marijuana, baseline | 0.142 | 0.078 | 1.812† | 0.199 | 0.096 | 2.067* |

| Depression, baseline | 0.015 | 0.051 | 0.300 | 0.065 | 0.067 | 0.963 |

| Sex risk, 12-mon. ON: | ||||||

| Sex risk, baseline | 0.501 | 0.058 | 8.613*** | 0.417 | 0.069 | 6.008*** |

| Marijuana, baseline | 0.121 | 0.092 | 1.319 | 0.054 | 0.108 | 0.501 |

| Depression, baseline | 0.045 | 0.066 | 0.684 | 0.207 | 0.069 | 3.013** |

| Sex risk, 18-mon. ON: | ||||||

| Sex risk, baseline | 0.515 | 0.058 | 8.839*** | 0.231 | 0.098 | 2.360* |

| Marijuana, baseline | 0.119 | 0.096 | 1.240 | 0.198 | 0.119 | 1.661† |

| Depression, baseline | 0.039 | 0.072 | 0.545 | 0.150 | 0.082 | 1.823† |

| Sex risk, baseline WITH: | ||||||

| Depression, baseline | 0.209 | 0.098 | 2.129* | 0.434 | 0.188 | 2.313* |

| Marijuana, baseline | 0.242 | 0.092 | 2.622** | 0.366 | 0.149 | 2.461* |

| Depression, baseline WITH: | ||||||

| Marijuana, baseline | −0.071 | 0.082 | −0.863 | −0.100 | 0.141 | −0.709 |

| Sex risk, 6-mon. WITH: | ||||||

| Sex risk, 3-mon. | 0.288 | 0.050 | 5.746*** | 0.375 | 0.078 | 4.802*** |

| Sex risk, 12-mon. WITH: | ||||||

| Sex risk, 3-mon. | 0.244 | 0.055 | 4.466*** | 0.295 | 0.070 | 4.191*** |

| Sex risk, 6-mon. | 0.267 | 0.056 | 4.761*** | 0.269 | 0.082 | 3.295*** |

| Sex risk, 18-mon. WITH: | ||||||

| Sex risk, 3-mon. | 0.159 | 0.058 | 2.744** | 0.322 | 0.085 | 3.813*** |

| Sex risk, 6-mon. | 0.289 | 0.058 | 4.998*** | 0.435 | 0.079 | 5.512*** |

| Sex risk, 12-mon. | 0.392 | 0.059 | 6.674*** | 0.497 | 0.077 | 6.458*** |

| Means: | ||||||

| Sex risk, baseline | 1.296 | 0.083 | 15.611*** | 1.346 | 0.114 | 11.780*** |

| Depression, baseline | −0.415 | 0.103 | −4.030*** | 0.647 | 0.130 | 4.964*** |

| Marijuana, baseline | 2.185 | 0.092 | 23.722*** | 2.054 | 0.116 | 17.768*** |

Note. All thresholds were significant, except sex risk, 18-month$1 for both males and females and sex risk, 12-month$1 for females. All variances were significant. Two-tailed p-values:

.10 > p > .05;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Fit of an Over Identified Model to the Data

Since the tested model was just identified, model fit information could not be obtained. In order to gain an idea of model fit, the correlation between depression and marijuana use at baseline was eliminated from the model. (There was no significant relationship between these two variables for the female and male youth.) Results indicate an excellent fit of the model to the data: chi-square = 1.25, df = 2, p = 0.54; RMSEA = 0.000; CFI = 1.000; TLI = 1.012. In particular, all residual correlations were at or near zero.2 (A copy of these analysis results is available from the corresponding author upon request.)

Analysis Involving Covariates

As noted earlier, separate analyses for female and male youths were estimated that examined the relationship between age, race (being African American), ethnicity (being Hispanic of any race), family income, who the youth lived with at study entry, and parent reports of family stressful events and trauma and baseline indicators of sexual risk behavior, marijuana use, and depression. As shown in Table 5, relatively few significant covariate relationships were found for each gender group, with age at study entry and family income accounting for almost all of the significant results. Among female truants, older girls reported marginally significant, greater involvement in sexual risk behavior measured at baseline; and girls living in families with higher incomes reported more involvement in sexual risk behavior at baseline, than girls living in families with more modest incomes. Among male truants, older boys reported more involvement in sexual risk behavior and marijuana use at baseline, than younger boys. In regard to family income, male truants living in households with more income reported greater involvement in sexual risk behavior and less depression at baseline.

Table 5.

Covariate Effects on Male (n = 187) and Female (n = 110) Truant Youth’s Sexual Risk Behavior, Marijuana Use, and Depression at Baseline (WLSMV Estimation)

| Covariate | Males | Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Risk | Marijuana | Depression | Sexual Risk | Marijuana | Depression | |

| Age | .201** | .232*** | −.023 | .171† | .061 | −156 |

| Race (African American = 1) | .349 | .185 | −.131 | .322 | −.026 | .143 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic = 1) | .150 | .035 | −.144 | .036 | −.084 | −.196 |

| Family Income | .163* | .025 | −.163* | .183* | .062 | .028 |

| Lives with (mother only = 1) | −.113 | .087 | −.068 | −.019 | .059 | −.208 |

| Family trauma | .086† | .044 | .127* | .076 | −.017 | .071 |

Note. Two-tailed p-values:

.10 > p > .05;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Further analysis was performed, in which each follow-up sexual risk variable was, in addition to being regressed on baseline sexual risk behavior, marijuana use and depression, also regressed on youth age, race, ethnicity, family income, living situation, and parental report of family trauma. The longitudinal effects reported earlier relating to baseline sexual risk behavior, marijuana use, and depression remained basically unchanged. (Due to space concerns, tables reporting the results in this section have been omitted. Copies are available from the corresponding author upon request.)

Examination of Brief Intervention Effect

Since this study involved a clinical trial, the effect of the intervention on the male and female youths’ involvement in sexual risk behavior over time was examined. Only one out of eight possible BI-sexual risk behavior effects was significant. Among female truants, receiving BI services (BI-Y or BI-YP) was related to more reported involvement in sexual risk behavior at 6-month follow-up, than receiving standard truancy services (STS).

In addition, the impact of the intervention on the hypothesized model was also examined by including the intervention effect (BI vs. STS) as a predictor of reported sexual risk behavior at the 3-month, 6-month, 12-month and 18-month follow-up time points. Results indicated no significant intervention effect for the males at each follow-up period. For females, no significant intervention effect was found for self-reported sexual risk behavior at the 3-month and 12-month follow-up periods. However, a significant, positive effect on reported sexual risk behavior was found for the 6-month and 18-month follow-up periods. It is important to note that these intervention effects for the females were not patterned. Further, the statistical significance of all relationships for males and females reported in Table 4, but one, remained unchanged when the intervention effect was included as a covariate in the analysis. Among females, the marginally significant relationship between baseline depression and sexual risk behavior at 18-month follow-up reported in Table 4 became significant when the intervention effect was included in the analysis.

Examination of Growth and Autoregressive Models

Given the longitudinal nature of the data, it was important to estimate growth and autoregressive models of the data. A multi-group (female and male) growth model analysis found a linear growth model fit the sexual risk behavior data. Level (baseline) sexual risk was significantly related to both baseline marijuana use and baseline depression for both gender groups. Importantly, however, neither baseline depression nor marijuana use was significantly related to linear trend sexual risk behavior for either gender group.

Autoregressive specification of the sexual risk behavior model involved including a regressive effect in which each follow-up time point sexual risk behavior variable was predicted by sexual risk behavior at its preceding follow-up time point (e.g., 12-month follow-up sexual risk behavior regressed on 6-month follow-up sexual risk behavior). Results of the multi-group analysis indicated a poor fit of the autoregressive model to the data. (Due to space concerns, detailed results of both these analyses have been omitted. Copies of the results are available from the corresponding author upon request.)

Discussion

The results indicate the truant youth involved in this study represented an at-risk segment of the population in regard to sexual risk behavior. Collectively, these youths reported high rates of sexual intercourse, intercourse without using a condom, and having sex with two or more people at each time point covered by the study. Further, at each time point, the male and female youths reported similar numbers of sexual risk behaviors in which they have been involved.

Based on self-report and urine test results, truant youths were significantly involved in marijuana use at baseline, with 48% of males and 42% of females having a positive urine tests. In regard to depression, from 36% to 56% of the truant youths reported feeling “down” for a continuous two week period, felt like crying for several days in a row, and had trouble sleeping for several days in a row. Nearly a quarter of the youths reported suicide ideation, and 8% indicted they had tried to take their lives. Consistent with other studies on depression among youth, females reported a significantly higher rate of depression than males (e.g., Lehrer et al., 2006; Shrier et al., 2001, 2002), with higher magnitudes of relationships between depression and marijuana use and sexual risk behavior across the five time points relative to males.

A major purpose of this study was to estimate a longitudinal model, separately for females and males, of the influence of baseline sexual risk behavior, marijuana use, and depression on the youths’ sexual risk behavior across four follow-up time points, over an 18-month follow-up period. Results indicated an excellent fit of the model to the data, although the hypothesized relationship between baseline marijuana use and depression was found to be non-significant for both females and males. Not surprisingly, the sexual risk behaviors were significantly related to one another over time. Of particular interest was the much stronger longitudinal effect of baseline depression on youths’ sexual risk behavior for females compared to the males. This finding is consistent with some research on general populations of youths (e.g., Lehrer et al., 2006; Shrier et al., 2001, 2002), but inconsistent with others (e.g., Hallfors et al., 2005).

Future research should examine the causal links between marijuana use, depression, and sexual risk behaviors across gender among lower-risk youth such as truants. Presently, the majority of research on this topic has relied on cross-sectional data. There is a need for more, longer term longitudinal research to assess the impact of depression and marijuana use on truant, and other at-risk, youths’ sexual risk behavior and associated STD/HIV. Such studies should enable analyses to be conducted examining bi-directional and mediating effects of substance use and depression on these youths’ sexual risk behavior over time. Moreover, there is a need to continue efforts to elucidate the dynamics of multi-level factors at the individual-level (e.g., biological, personality), microsystem-level (e.g., family), and mesosystem-level (e.g., school, community) underlying sexual risk behavior over time (Voisin et al., 2012). An ecological focus on this critical public health issue is indicated.

Interestingly, in the covariate analyses for the hypothesized model, family income was positively and significantly related to baseline sexual risk behavior. This finding contradicts the limited research on the association between socioeconomic status and sexual risk behaviors. Most research suggests low socioeconomic status is related to higher levels of sexual risk behavior (e.g., Cheney et al., 2015; Crichton, Hickman, Campbell, Batista-Ferrer, & Macleod, 2015). However, most of these studies operationalize socioeconomic status using multiple indicators including family structure, parent’s education level, parent’s occupation, and family income or poverty level, and tend to find no significant association between income and sexual risk behaviors (e.g., Cubbin, Vesely, Braveman, & Oman, 2011; Santelli, Lowry, Brener, & Robin, 2000). It is, therefore, possible that the effect reported in the present study is spurious, and would be reduced to non-significance if other indicators of socioeconomic status were available in the data and included in the model. Future research should examine the generalizability of this study using multiple indicators of socioeconomic status.

Further this study found little indication of a Brief Intervention effect on the youths’ sexual risk behavior over time. This is not a surprising outcome, as the BI was not designed to target sexual risk behavior specifically, but rather the intervention focused on helping adolescents recognize causes and consequences of their substance use, develop goals for changing their substance use behavior, and commit to avoiding substance use. Indeed, for the adolescent girls in the study, the intervention appeared to have a slightly deleterious effect, increasing the risk of sexual behaviors at the 6-month and 12-month follow-up periods. Importantly, these effects may reflect other factors that were not captured in the data such as life events and decisions that were more important than or a consequence of the intervention. It is possible that girls who were in the intervention were more likely to pull themselves away from habits and behaviors that increased their risk of substance use by focusing on more positive activities and social interactions, which may have increased their risk of sexual activity. For example, a girl in the intervention who acknowledged she used substances as a form of retreatism may have been encouraged to participate in school organizations and activities to improve social interaction and reduce substance use. This social interaction may have led to her increased contact with others willing to participate in sexual activities. Unfortunately, the data do not contain details that might help elucidate this intervention effect. Future research should include other situational and life-course factors that may affect sexual risk behaviors, among girls especially. Given the significant relationship found between the youths’ sexual risk behavior and marijuana use at baseline, consideration should still be given to revising intervention protocols addressing truant youth substance use by including attention to the issues of depression and sexual risk behavior. In this vein, special consideration should be given to addressing longer term depression issues among female truant youth.

To the authors’ best knowledge, this is the first study examining the longitudinal relationships between truant youths’ marijuana use, depression and sexual risk behavior. It would be important to replicate this study among truant youth in other jurisdictions, reflecting different socio-demographic characteristics, to assess the external validity of the findings on this important at-risk group of youth.

There were several limitations to this study. First, there were limitations due to the nature of the sample, which consisted primarily of truant youth who had been detained by law enforcement for truancy or had been placed in a diversion program and were known to have truancy issues. Hence, the results of the study may not generalize to truant youth who do not have such agency contact/involvement. Second, similar to a limitation in the risky sexual behavior research among adolescents the sexual risk behavior data were based on self-reports. Third, some of the measures could have been improved. For example the depression symptoms indicator only captures general depressive symptoms, and is not a DSM indicator of clinical levels of depression. Also, some of the family characteristics, such as traumatic events, were measured based on parents as the informant, not the youth. Since the traumatic events indicator captures serious events such as injury requiring hospitalization, serious illness, death, divorce, eviction, unemployment of a parent, and legal problems resulting in jail or detention, however, we believe the youths in the study was be aware of and experience the effects of these traumatic events.

Based on the results of this study, there is serious need to provide quality screening-assessment and sexual risk reduction intervention services to truant youth. Implementing interventions targeting substance use, depression issues, and sexual risk behavior are needed to help truant youth engage in healthier behavior and avoid adverse outcomes such as STDs and HIV/AIDS.

Footnotes

Following the NIDA approved protocol for the study, the length of follow-up was premised on year of entry into the project. Since some youth had missing follow-up data due to this sampling design, as well as typical attrition, the multi-group analysis of the just identified model was replicated involving only cases with complete data on all variables in the model. The analysis involved 136 male and 74 female youths. With one exception, the same pattern of results was found as those including missing data. For the one exception, the original analysis involving estimation of missing data found a significant relationship between sexual risk behavior at 6-month follow-up and baseline marijuana use among females; however, this relationship was non-significant in the analysis involving cases with complete data on all variables. Therefore, missing data due to sampling design did not substantively affect the model.

As with the just identified model, the over identified model was replicated using only cases with complete data on all variables in the model to gain an idea of model fit by eliminating the correlation between depression and marijuana use at baseline. Consistent with the version of the model containing missing data, the results indicated an excellent fit of the model to the data: chi-square = 2.19, df = 2, p = 0.33; RMSEA = 0.030; CFI = 1.000; TLI = 0.996. In particular, all residual correlations were at or near zero. Therefore, missing data due to the sampling design did not substantively affect the model.

Contributor Information

Richard Dembo, University of South Florida, 4202 E. Fowler Avenue, Tampa. FL 33620

Julie Krupa, University of South Florida, 4202 E. Fowler Avenue, Tampa. FL 33620

Jennifer Wareham, Wayne State University, 3278 Faculty/Administrative Building, Detroit, MI 48202

James Schmeidler, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, N.Y. 10029

Ralph J. DiClemente, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322

References

- Abram KM, Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:1097–1108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R. Building on the foundation of general strain theory: Specifying the types of strain most likely to lead to crime and delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38:319–361. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R, White HR. An empirical test of general strain theory. Criminology. 1992;30:475–499. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative Fit Indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovasso G. Cannabis abuse as a risk factor for depressive symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:2033–2037. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgeland J, Dilulio JJ, Jr, Morison KB. The silent epidemic: Perspectives of high school dropouts. Seattle, WA: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; 2006. A report by Civic Enterprises in association with Peter D. Hart Research Associates for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth Online-High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey. 2011 Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/yrbs.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 4. Vol. 17. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_hssr_vol_17_no_4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2013. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Wagner F, Anthony J. Marijuana use and the risk of major depressive episode: Epidemiological evidence from the United States National Comorbidity Survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2002;37:199–203. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0541-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Stiffman AR, Cheng LC, Dore P. Mental health, social environment and sexual risk behaviors of adolescent service users: A gender comparison. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1997;6:9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cheney MK, Oman RF, Vesely SK, Aspy CB, Tolma EL, John R. Prospective association between negative life events and initiation of sexual intercourse: The influence of family structure and family income. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105:598–604. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crichton J, Hickman M, Campbell R, Batista-Ferrer H, Macleod J. Socioeconomic factors and other sources of variation in the prevalence of genital chlamydia infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:7–29. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2069-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubbin C, Vesely SK, Braveman PA, Oman RF. Socioeconomic factors and health risk behaviors among adolescents. American Journal of Health Behaviors. 2011;35:28–39. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.35.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Briones Robinson R, Barrett K, Ungaro R, Winters KC, Belenko S, Karas LM, Gulledge L, Wareham J. Brief intervention for truant youth sexual risk behavior and marijuana use. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2014;23(5):318–333. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2014.928116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Briones-Robinson R, Barrett K, Winters KC, Ungaro R, Karas L, Wareham J, Belenko S. Psychosocial problems among truant youths: A multi-group, exploratory structural equation modeling analysis. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2012;21(5):440–465. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2012.724290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Briones Robinson R, Ungaro R, Barrett K, Gulledge L, Winters KC, Belenko S, Karas LM, Wareham J. Brief intervention for truant youth sexual risk behavior and alcohol use: A parallel process growth model analysis. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2014;23(3):155–168. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2013.786643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Briones Robinson R, Wareham J, Winters KC, Ungaro R, Karas LM. A longitudinal study of truant youths’ involvement in sexual risk behavior. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2016;25(2):89–104. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2013.872069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Wareham J, Krupa JM, Winters KC. Sexual risk behavior among male and female truant youths: Exploratory, multi-group latent class analysis. Journal of Alcoholism & Drug Dependence. doi: 10.4172/2329-6488.1000226. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Wareham J, Schmeidler J, Briones-Robinson R, Winters KC. Differential effects of mental health problems among truant youths. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2014:1–25. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Wareham J, Schmeidler J, Winters KC. Longitudinal effects of a second-order multi-problem factor of sexual risk, marijuana use, and delinquency on future arrest among truant youth. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2016.1153554. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Brener N, Kann LK. Associations of health risk behaviors with school absenteeism. Does having permission for the absence make a difference? Journal of School Health. 2008;78:223–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garry EM. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Vol. 76. Washington D.C: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice Delinquency Prevention; 2001. Truancy, first step in a lifetime of problems. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorenko EL, Edwards L, Chapman J. Cannabis use among juvenile detainees: Typology, frequency and association. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2015;25:54–65. doi: 10.1002/cbm.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Ford CA, Halpern CT, Brodish PH, Iritani B. Adolescent depression and suicide risk: Association with sex and drug behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Bauer D, Ford CA, Halpern CT. Which comes first in adolescence—sex and drugs or depression? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Magnan RE, Bryan AD. Associations of marijuana use and sex-related marijuana expectancies with HIV/STD risk behavior in high-risk adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:404–414. doi: 10.1037/a0019844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Thornberry TP, Huizinga DH. A discrete-time survival analysis of the relationship between truancy and the onset of marijuana use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(1):5–15. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM, Coffey C, Patton GC, Tait R, Smart D, … Hutchinson DM. Cannabis and depression: An integrative data analysis of four Australasian cohorts. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;126:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DYC, Murphy DA, Hser YI. Developmental trajectory of sexual risk behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood. Youth & Society. 2012;44:479–499. doi: 10.1177/0044118X11406747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on drug use: 1975–2013: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Komro KA, Tobler AL, Maldonado-Molina MM, Perry CL. Effects of alcohol use initiation patterns on high-risk behaviors among urban, low-income, young adolescents. Prevention Science. 2010;11(1):14–23. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0144-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer JA, Shrier LA, Gortmaker S, Buka S. Depressive symptoms as a longitudinal predictor of sexual risk behaviors among US middle and high school students. Pediatrics. 2006;118:189–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JV, Abramowitz S, Koenig LJ, Chandwani S, Orban L. Negative life events and depression in adolescents with HIV: A stress and coping analysis. AIDS Care. 2015;27(10):1265–1274. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1050984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP. Young children who commit crime: Epidemiology, developmental origins, risk factors, early interventions, and policy implications. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12(4):737–762. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee R, Williams S, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. A longitudinal study of cannabis use and mental health from adolescence to early adulthood. Addiction. 2000;95:491–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9544912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, Harrington H, Houts R, Keefe RSE, Moffitt TE. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:E2657–2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthèn LK, Muthèn BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthèn & Muthèn; 1998–2012. 7th version. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for School Engagement. Lessons learned from four truancy demonstration sites. Denver, CO: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Lynskey M, Hall W. Cannabis use and mental health in youth people: Cohort study. The BMJ. 2002;325:1195–1198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Lowry R, Brener ND, Robin L. The association of sexual behaviors with socioeconomic status, family structure, and race/ethnicity among US adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1582–1588. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.10.1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeige S, Levin M, Broaddus M, Bryan A. Randomized trial of group interventions to reduce HIV/STD risk and change theoretical mediators among detained adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:38–50. doi: 10.1037/a0014513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier LA, Harris SK, Beardslee WR. Temporal associations between depressive symptoms and self-reported sexually transmitted disease among adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:599–606. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier LA, Harris SK, Kurland M, Knight JR. Substance use problems and associated psychiatric symptoms among adolescents in primary care. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e699–e705. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.e699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier LA, Harris SK, Sternberg M, Beardslee WR. Associations of depression, self-esteem, and substance use with sexual risk among adolescents. Preventive Medicine. 2001;33:179–189. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein LAR, Lebeau R, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Golembeske C, Monti PM. Motivational interviewing for incarcerated adolescents: Effects of depressive symptoms on reducing alcohol and marijuana use after release. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:497–506. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Elkington KS, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Mericle AA, Washburn JJ. Major mental disorders, substance use disorders, comorbidity, and HIV-AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:823–828. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.7.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Mericle AA, McClelland GM, Abram KM. HIV and AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees: Implications for public health policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:906–912. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;38:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR, Hong JS, King K. Ecological factors associated with sexual risk behaviors among detained adolescents: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34:1983–1991. [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Henly GA. Adolescent Diagnostic Interview Schedule and Manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Lee S, Botzet A, Fahnhorst T, Nicholson A. One-year outcomes and mediators of a brief intervention for drug abusing adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:464–474. doi: 10.1037/a0035041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Leitten W. Brief intervention for drug-abusing adolescents in a school setting. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:249–254. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Stinchfield RD. Adolescent Diagnostic Interview-Parent. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Witkiewitz K, McMahon RJ, Dodge KA Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. A parallel process growth mixture model of conduct problems and substance us with risky sexual behavior. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;111:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young P, Rahdert E. Development of a POSIT-related HIV/STD risk scale. Bethesda, MA: NOVA Research Company; 2000. [Google Scholar]