Abstract

Identifying regulators of placental breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) expression is critical as down-regulation of this transporter may increase exposure of the fetus to xenobiotics. Here we sought to test whether the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) regulates BCRP expression in the placenta. To test this, human BeWo placental choriocarcinoma cells were cultured with the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone or the PPARγ antagonist T0070907 for 24 h. Messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of syncytialization markers, GCM1 and hCGβ, as well as BCRP increased with PPARγ agonist treatment. Conversely, BCRP mRNA and protein expression decreased 30–50% with PPARγ antagonist treatment. Rosiglitazone enhanced BCRP protein expression and transport activity, resulting in a 20% greater efflux of the substrate Hoechst 33342 compared to control cells. These results suggest that PPARγ can up-regulate BCRP expression in the placenta, which may be important in understanding mechanisms that protect the fetus from xenobiotic exposure during development.

Keywords: Placenta, Trophoblast, BCRP, ABCG2, PPAR gamma

INTRODUCTION

The human placenta supports the normal growth and development of the fetus. Placental villi are lined with syncytiotrophoblasts that produce hormones such as human chorionic gonadotropin beta (hCGβ) and also express transporters that regulate the maternal-to-fetal and fetal-to-maternal transfer of chemicals. One such transporter is the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP, ABCG2), which is highly enriched within the placenta on the apical (maternal) surface of syncytiotrophoblasts and is an important part of the blood-placental barrier (1–4). BCRP is a half-transporter protein that requires the formation of homodimers and oligomers to function properly (5). BCRP has over 100 substrates (reviewed in (6)) including environmental chemicals (perfluorooctanoic acid, bisphenol A) (7,8), mycotoxins (zearalenone, aflatoxin B1) (9,10), chemotherapeutic drugs (mitoxantrone, doxorubicin, daunorubicin) (2), photosensitizers (pheophorbide A, protoporphyrin IX) (11) and others such as cimetidine (12), glyburide (13), phytoestrogens (genistein and daidzein) (14), nitrofurantoin (15), and rosuvastatin (16). Previous studies show that mouse fetuses lacking the Bcrp transporter have elevated concentrations of glyburide, nitrofurantoin, and genistein (14,15,17). In addition to xenobiotics, BCRP has been shown to transport the fluorescent dye Hoechst 33342 (18), which is often used as a marker of BCRP function. Human BeWo choriocarcinoma cells express transporters and secrete hormones such as hCGβ. BeWo cells highly express BCRP (19,20) and have been shown to transport BCRP substrates including Hoechst 33342 (20), mitoxantrone (4), and glyburide (21). Thus, BeWo cells are routinely used to study the regulation and function of the placental BCRP transporter (22,23).

A number of nuclear receptor pathways including the progesterone and estrogen receptors have been explored as potential regulators of BCRP expression in BeWo cells (24,25). However, little attention has been placed on the ability of xenobiotic-activated receptors to transactivate the ABCG2 gene in the placenta. For example, a study using human brain dendritic cells has identified the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) as a novel regulator of BCRP (26). Ligand-activated PPARγ binds to a 150-bp portion (−3946/−3796) of a conserved region in the promoter of the human ABCG2 gene (26). PPARγ is an important regulator of placenta development such that mice lacking expression of PPARγ do not develop normally. Placentas lacking PPARγ exhibit altered terminal differentiation of trophoblasts and placental vascularization. PPARγ homozygous null (−/−) embryos cannot be detected on gestation day 12.5 and beyond (27). A second study found that no PPARγ−/− pups were born in 62 offspring of heterozygous PPARγ intercrosses; likewise, no viable PPARγ−/− embryos were detected 11.5 days post coitum pointing to an indispensible role for this nuclear receptor in placental development (28). Preliminary studies suggest that PPARγ can activate BCRP mRNA expression in placental cells in coordination with the induction of syncytialization genes, including the transcriptional regulator of syncytin genes known as glial cells missing homolog 1 (GCM1), and the secretion of hCGβ (29,30). Moreover, mouse trophoblast stem cells lacking PPARγ have reduced expression of syncytin A and lower numbers of multinucleated syncytiotrophoblasts (31). The fact that placenta is highly enriched in both BCRP and PPARγ expression led us to consider whether this transcriptional pathway could be activated by an exogenous ligand and further increase BCRP levels. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine whether PPARγ regulates BCRP expression and function in placental cells. This was accomplished by treating BeWo cells with a pharmacological agonist (rosiglitazone) and an antagonist (T0070907) and evaluating BCRP mRNA and protein expression as well the ability to efflux the prototypical substrate Hoechst 33342 (18,32).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Unless otherwise specified, chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Cell Culture

BeWo choriocarcinoma placenta cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium: F-12 (1:1, ATCC) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and were used in experiments when they reached 80 to 90% confluence.

BeWo cells (3 × 104 cells/well) were grown on six-well plates for 3 days. Fresh media was supplied on the second day. For the dose-response study, rosiglitazone (1–30 μM) was dissolved in 0.24% DMSO and applied to cells for 24 h. For other studies, BeWo cells were treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), rosiglitazone (15 μM), T0070907 (1 or 10 μM) or the combination of rosiglitazone (15 μM) and T0070907 (1 μM) for 24 h.

RNA Isolation and Real-Time Quantitative PCR

After an 24 h incubation with vehicle, rosiglitazone, and/or T0070907, cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed with buffer RLT (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) containing 1% β-mercaptoethanol. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Integrity and concentration of RNA were assessed with a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Complementary DNA was generated with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit with 500 ng total RNA (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems) was used for detection of amplified products. qPCR was performed in a 384-well plate using a ViiA7 RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences have been provided in Table 1. Ct values were converted to delta Ct values by comparing to the reference gene, ribosomal protein 13a (RPL13A) and further to delta delta Ct by comparing to the respective control-treated cells (33).

TABLE 1.

Primer Sequences for qPCR

| Genes | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| BCRP | ATCAGCTGGTTATCACTGTGAGGCC | CAATGTCGGATGGATGAAACCCAG |

| GCM1 | TGAGGCTGCTCTCAAACTCCTGAT | AGACGGGACAGGTTTCCATTCCTT |

| hCGβ | GCACCAAGGATCGAGATGTT | GCACATTGACAGCTGAGAGC |

| RPL13A | GGTGCAGGTCCTGGTGCTTGA | GGCCTCGGGAAGGGTTGGTG |

Western Blot

BeWo cells were treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), rosiglitazone (15 μM), or T0070907 (10 μM). After 24 h, cells were harvested and centrifuged for 10 min at the speed of 1500 rpm to obtain cell pellets. Lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail) was added to the cell pellets. Samples were centrifuged for 3 min at 1000 rpm before performing analysis. Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Western blot analysis was performed by loading 10 μg protein homogenate per sample on polyacrylamide 4–12% Bis–Tris gels (Life Technologies), which were resolved by electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred from gels onto a PVDF membrane overnight. The membrane was then blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk in PBS with 0.5% Tween-20 for 1 h. BCRP (BXP-53, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and β-ACTIN (ab8227, Abcam) primary antibodies were diluted in 2% non-fat dry milk in PBS with 0.5% Tween-20 and incubated with the membranes at dilutions of 1:5000 and 1:2000, respectively. After washing, the membrane was incubated with species-specific HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO): anti-rat IgG (BCRP) and anti-rabbit (β-ACTIN) at dilutions of 1:2000. SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology) was added to the blots for 2 min. Detection and semiquantitation of protein bands were performed with a FluorChem imager (ProteinSimple, Santa Clara, CA). The density of bands was assessed using an Alpha Viewer (ProteinSimple) and normalized to β-ACTIN levels.

Fluorescent Substrate Transport and Cell Size Assays

The BCRP-specific fluorescent substrate, Hoechst 33342, was used to quantify BCRP function (21). Following treatments, BeWo cells were trypsinized and added to a 96-well plate. Following centrifugation (500xg, 5 min, 8°C) and removal of the media, cells were loaded with Hoechst 33342 (3 μM) for 30 min at 37°C and 5% CO2 (uptake phase). A subset of control cells were incubated with the BCRP-specific inhibitor, Ko143 (1 μM). Media was removed and cells were resuspended in substrate-free media with or without Ko143 for 1 h (efflux phase). Following the efflux phase, cells were centrifuged (500xg, 5 min, 8°C), washed, and resuspended in cold PBS for quantification of intracellular fluorescence using the Cellometer Vision automated cell counter (Nexcelom Bioscience, Lawrence, MA). Because BeWo cells stimulated to undergo cell fusion are larger in size (34), cell suspensions (20 μl) were added to the cell counting chamber and analyzed for cell size and cell number using bright field images. A similar number of cells (between 750–1500) were counted for each treatment group. A VB-450-302 filter (excitation/emission: 375/450 nm) allowed for intracellular fluorescence detection of Hoechst 33342.

Immunocytochemistry

BeWo cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in chamber slides and grown until 90% confluent. After treatment with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), rosiglitazone (15 μM), or T0070907 (1 μM) for 24 h, cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, then blocked with 5% goat serum in 0.1% Triton X in PBS for 1 h. The primary antibody against Na+/K+ ATPase (ab76020, Abcam) was diluted 1:200 in 5% goat serum in PBS-Triton X and applied overnight. After washing, a goat anti-rabbit IgG 594 (red) (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was diluted 1:200 in 5% goat serum in PBS-Triton X and applied for 1 h. Slides were rinsed in PBS-Triton X, PBS, and deionized water. One drop of Prolong Gold with DAPI was added to each slide and covered with a coverslip. Images were acquired at 320X magnification (objective 20X, eye objective 10X, 1.6X setting) using an Olympus OlyVIA VS120 microscope (Olympus Corp., Center Valley, PA).

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SE and all statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls post-hoc test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

GCM1 and hCGβ mRNA Expression in Response to PPARγ Agonism and Antagonism

Rosiglitazone was used to activate PPARγ at concentrations (1–30 μM, 24 h) that did not alter cell viability or cytotoxicity as determined by the alamarBlue assay and lactate dehydrogenase release, respectively (data not shown). Similarly, PPARγ was inhibited using T0070907 at concentrations (1–10 μM, 24 h) that did not change cell viability or cytotoxicity (data not shown).

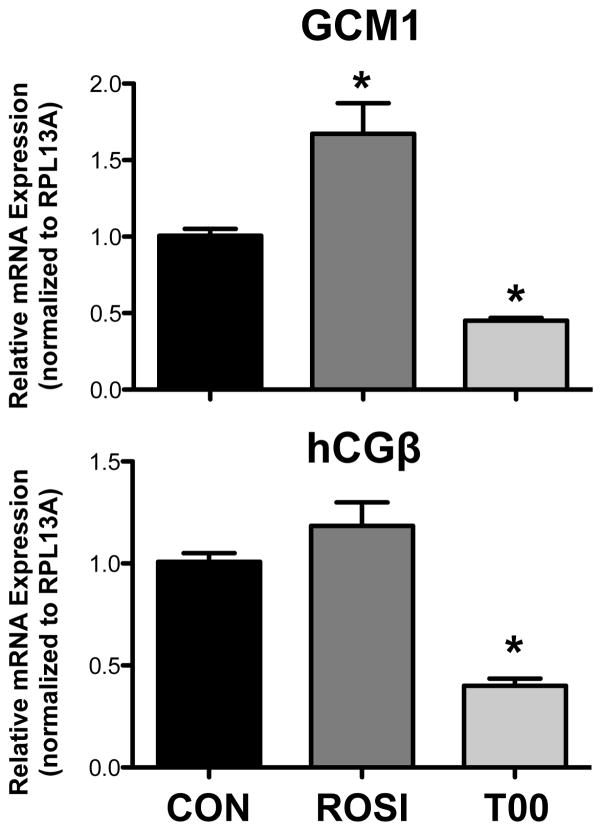

Markers of placental trophoblast syncytialization (GCM1 and hCGβ) were quantified using qPCR analysis. Treatment of BeWo cells with rosiglitazone increased GCM1 mRNA by 66% and tended to elevate hCGβ mRNA by 18% mRNA although not statistically significant (Figure 1). Conversely, treatment with T0070907 decreased both GCM1 and hCGβ mRNAs by 55% and 60%, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1. GCM1 and hCGβ mRNA Expression in Response to PPARγ Agonism and Antagonism.

BeWo cells were treated with the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone (ROSI, 15 μM) and PPARγ antagonist T0070907 (T00, 10 μM) for 24 h. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of GCM1 and hCGβ mRNA was performed with SYBR Green fluorescence detection using a ViiA7 RT-PCR system. Ribosomal protein L13a (RPL13A) was used as a reference gene (n=2 experiments, 4 replicates/experiment). Data are presented as mean ± S.E. * p < 0.05 compared to control (CON).

Cell Morphology and Size in Response to PPARγ Agonism and Antagonism

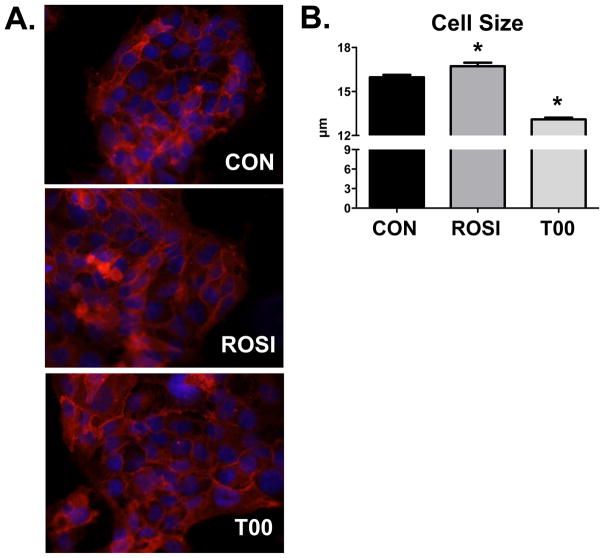

Previous studies demonstrate that induction of syncytialization in BeWo cells leads to an increase in mean cell size (34). Therefore, we assessed the degree of syncytialization using immunofluorescence and cell size measurements. Morphological analysis showed a similar degree of multinucleated cells between vehicle-, rosiglitazone-, and T0070907-treated groups (Figure 2A). A slight but significant increase in BeWo cell size as determined by an automated cell counter (Nexcelom Cellometer) was observed following treatment with rosiglitazone (Figure 2B). Conversely, T0070907 decreased BeWo cell size.

Figure 2. Cell Morphology and Size in Response to PPARγ Agonism and Antagonism.

(A) The number of nuclei per cell, an indicator of syncytialization, was qualitatively assessed after treatment with rosiglitazone (ROSI, 15 μM) and T0070907 (T00, 1 μM). Neither treatment differed from control (CON) cells. Plasma membranes were stained for the Na+/K+ ATPase (red) and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Magnification 320X. (B) Cell size was quantified using a Nexcelom Cellometer cell counter and presented as mean ± S.E. * p < 0.05 compared to control (CON).

BCRP mRNA Expression in Response to PPARγ Agonism and Antagonism

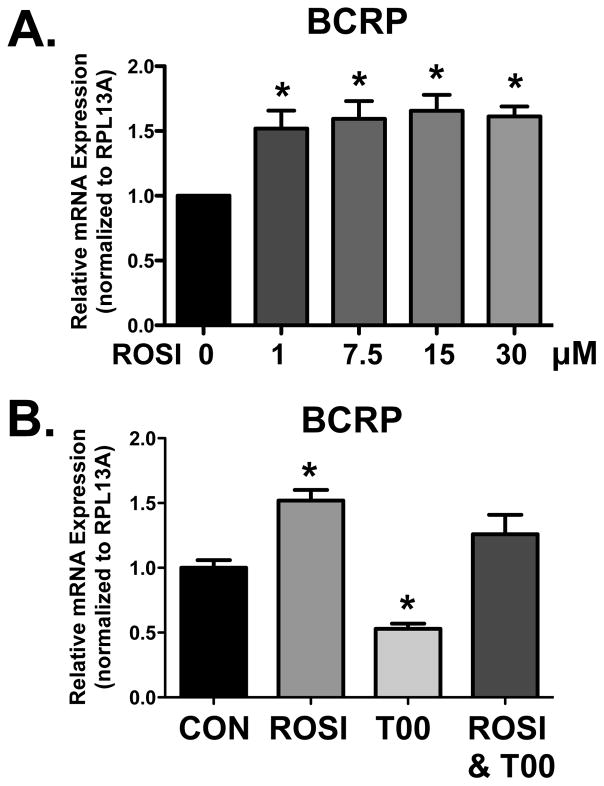

BCRP mRNA was quantified in BeWo cells treated with increasing concentrations of rosiglitazone for 24 h. Compared to vehicle-treated cells, a 50% increase in BCRP mRNA expression was observed in the cells treated with rosiglitazone concentrations as low as 1 μM (Figure 3A). BCRP mRNA expression was not enhanced much further at higher concentrations of rosiglitazone. Quantification of BCRP mRNA was also performed following exposure to rosiglitazone, T0070907, and the combination of rosiglitazone with T0070907 for 24 h (Figure 3B). BCRP mRNA expression was increased by 50% in cells treated with rosiglitazone, decreased by 50% with T0070907, and was unchanged following the combination treatment (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. BCRP mRNA Expression in Response to PPARγ Agonism and Antagonism.

(A) BeWo cells were treated with increasing concentrations of PPARγ agonist, rosiglitazone, and incubated for 24 h (n=5 experiments, 4 replicates/experiment). (B) BeWo cells were treated with the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone (ROSI, 15 μM), PPARγ antagonist T0070907 (T00, 1 μM), and the combination of rosiglitazone (15 μM) and T0070907 (1 μM) for 24 h (n=1 experiment, 4 replicates/experiment). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of BCRP mRNA was performed with SYBR Green fluorescence detection using a ViiA7 RT-PCR system. Ribosomal protein L13a (RPL13A) was used as a reference gene. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. * p < 0.05 compared to control (CON, 0 μM).

BCRP Protein Expression and Transporter Function in Response to PPARγ Agonism and Antagonism

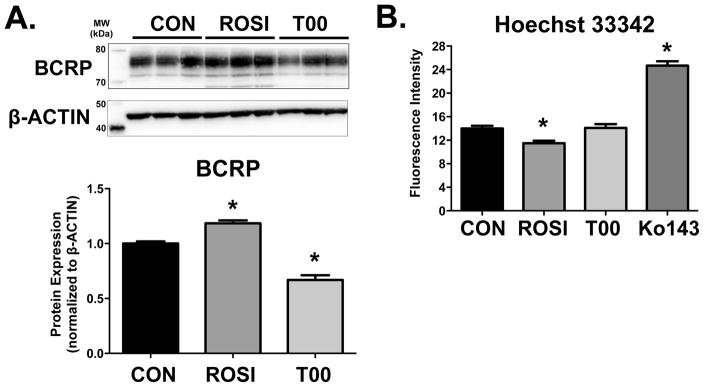

Western Blot analysis was performed on BeWo cell lysates following treatment with vehicle, rosiglitazone, or T0070907 for 24 h. Changes in BCRP protein mirrored the regulation of mRNA. BCRP protein expression was increased by 20% in cells treated with rosiglitazone and decreased by 30% in cells treated with T0070907 (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. BCRP Protein Expression and Transporter Function in Response to PPARγ Agonism and Antagonism.

(A) BCRP protein expression in BeWo cells was determined 24 h after PPARγ agonism (rosiglitazone, ROSI, 15 μM) and PPARγ antagonism (T0070907, T00, 10 μM). β-ACTIN was used as the loading control. BCRP expression was compared to control cells (CON, set to 1.0). n=2 experiments, 3 replicates/experiment. (B) Fluorescence intensity of Hoechst 33343 dye retained in BeWo cells was quantified 24 h after PPARγ agonism (ROSI, 15 μM) and PPARγ antagonism (T0070907, T00, 1 μM). Ko143 (1 μM) was used as positive control inhibitor of BCRP function. n=2 experiments, 5–6 replicates/experiment. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. * p < 0.05 compared to control (CON).

The Hoechst 33342 accumulation assay was used to assess BCRP activity in BeWo cells after rosiglitazone or T0070907 treatment for 24 h. The BCRP specific inhibitor Ko143 (1 μM) was used as a positive control and revealed a 175% increase in the retention of Hoechst (Figure 4B). Consistent with the induction of BCRP protein and presumably activity, the intracellular concentration of Hoechst 33342 was reduced by 20% in BeWo cells treated with rosiglitazone. Despite the down-regulation of BCRP expression by T0070907, no change in Hoechst 33342 accumulation was observed.

DISCUSSION

Because BCRP is a critical part of the blood-placental barrier, there is interest in understanding how transcriptional pathways regulate this transporter’s expression and function. PPARγ is a candidate for regulating BCRP transcription since its ligands can induce expression in human dendritic (26) and intestinal cells (35). More recent data also suggest that BCRP mRNA can be induced by the PPARγ activator troglitazone in primary human cytotrophoblasts (29). Therefore, we assessed the ability of a PPARγ agonist and antagonist to up- and down-regulate BCRP expression and function, respectively. We observed that enhanced BCRP expression and function was associated with induction of GCM1 and hCGβ, two markers of syncytialization, as well as a modest increase in placental BeWo cell size. Moreover, inhibition of basal PPARγ activity reduced BCRP mRNA and protein levels although no change in function, as assessed by Hoechst 33342 retention, was observed. Collectively, these data point to PPARγ as a novel regulator of the blood-placental barrier.

Induction of BCRP expression is a feature of syncytializing trophoblasts (36). Treatment with forskolin increases cyclic AMP concentrations resulting in cell fusion and increased expression of BCRP (36). Similarly, the mycoestrogen zearalenone was able to stimulate both syncytialization of BeWo cells as well as induction of BCRP (36). Moreover, down-regulation of BCRP in BeWo cells has demonstrated an intrinsic role for this transporter in the up-regulation of syncytialization markers (37).

A disconnect between BCRP protein down-regulation by T0070907 and no change in intracellular Hoecsht concentrations was surprising. These data suggest that sufficient BCRP function was present despite the significant decline in protein levels. Further studies characterizing the kinetics of Hoescht efflux or employing an alternate BCRP substrate may suggest a reduction in BCRP function following treatment with T0070907.

There is great interest in determining whether placental BCRP expression is altered in diseases of pregnancy. Abnormal placentation can result in preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count), and intrauterine growth restriction (reviewed in (38,39)). Reduced BCRP mRNA expression in placentas has been observed in preeclamptic pregnancies complicated by HELLP syndrome (29,40). Likewise, BCRP mRNA is reduced in placentas from pregnancies with intrauterine growth restriction (41). This corresponds with a down-regulation of syncytin-1 mRNA in both diseases of pregnancy (29) and a decrease in PPARγ expression in placentas from preeclamptic women (42). Interestingly, recent data point to a potential role for PPARγ agonists as a therapeutic intervention for the treatment of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia by enhancing signaling through the regulator of G protein (heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding protein) (43). Collectively, these data suggest that targeting of PPARγ to treat disorders of pregnancy may also restore BCRP expression and function.

There is growing interest in environmental chemicals that function as PPARγ agonists and contribute to obesity and altered lipid signaling. Phthalates, such as monoethylhexylphthalate, have been recognized as PPARγ agonists (44) although they have little interaction with BCRP directly (7). Likewise, emerging research has pointed to organotins, including tributyltin and triphenyltin, as activators of PPARγ signaling and stimulators of adipocyte differentiation (45,46). Recent analysis has revealed that components of house dust can activate PPARγ signaling (47,48). Chemicals in house dust include flame retardants triphenyl phosphate and metabolites such as diphenyl phosphate, tetrabromobenzoic acid, and tetrabromo mono(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate, which all exhibit an affinity for PPARγ (47). In particular, binding of tetrabromo mono(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate was similar to that of rosiglitazone (47). Because of the widespread exposure to these chemicals, it will be important to determine whether these chemicals stimulate placental hormone secretion and BCRP expression by enhancing PPARγ signaling and triggering syncytialization.

As an efflux pump, BCRP is an important component of the blood-placenta barrier. The current findings build upon prior investigations pointing to sex steroid receptors as modulators of BCRP expression in placenta (24,25). We have identified PPARγ as a novel transcription factor that can induce BCRP mRNA, protein, and activity in placental cells. Future studies aim to understand the ability of PPARγ to enhance placental BCRP function in vivo, particularly in animal models of pregnancy disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences [Grants ES020522, ES005022, ES007148, ES020721], a component of the National Institutes of Health. Kristin Bircsak was supported by predoctoral fellowships from the American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education (AFPE) and Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). NIEHS, AFPE, and PhRMA did not have any role in the conduct of the study, interpretation of data or decision to publish. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, AFPE, of PhRMA.

Non-Standard Abbreviations

- BCRP

breast cancer resistance protein

- CON

control

- HELLP

hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count

- GCM1

glial cells missing homolog 1

- hCGβ

human chorionic gonadotropin beta

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- RPL13A

ribosomal protein 13a

- ROSI

rosiglitazone

- T00

T0070907

References

- 1.Allikmets R, Schriml LM, Hutchinson A, Romano-Spica V, Dean M. A human placenta-specific ATP-binding cassette gene (ABCP) on chromosome 4q22 that is involved in multidrug resistance. Cancer Res. 1998;58(23):5337–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle LA, Yang W, Abruzzo LV, Krogmann T, Gao Y, Rishi AK, Ross DD. A multidrug resistance transporter from human MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(26):15665–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maliepaard M, Scheffer GL, Faneyte IF, van Gastelen MA, Pijnenborg AC, Schinkel AH, van De Vijver MJ, Scheper RJ, Schellens JH. Subcellular localization and distribution of the breast cancer resistance protein transporter in normal human tissues. Cancer Res. 2001;61(8):3458–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ceckova M, Libra A, Pavek P, Nachtigal P, Brabec M, Fuchs R, Staud F. Expression and functional activity of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP, ABCG2) transporter in the human choriocarcinoma cell line BeWo. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33(1–2):58–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henriksen U, Gether U, Litman T. Effect of Walker A mutation (K86M) on oligomerization and surface targeting of the multidrug resistance transporter ABCG2. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 7):1417–26. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klaassen CD, Aleksunes LM. Xenobiotic, bile acid, and cholesterol transporters: function and regulation. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62(1):1–96. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dankers AC, Roelofs MJ, Piersma AH, Sweep FC, Russel FG, van den Berg M, van Duursen MB, Masereeuw R. Endocrine disruptors differentially target ATP-binding cassette transporters in the blood-testis barrier and affect Leydig cell testosterone secretion in vitro. Toxicol Sci. 2013;136(2):382–91. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazur CS, Marchitti SA, Dimova M, Kenneke JF, Lumen A, Fisher J. Human and rat ABC transporter efflux of bisphenol a and bisphenol a glucuronide: interspecies comparison and implications for pharmacokinetic assessment. Toxicol Sci. 2012;128(2):317–25. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Herwaarden AE, Wagenaar E, Karnekamp B, Merino G, Jonker JW, Schinkel AH. Breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp1/Abcg2) reduces systemic exposure of the dietary carcinogens aflatoxin B1, IQ and Trp-P-1 but also mediates their secretion into breast milk. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(1):123–30. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao J, Wang Q, Bircsak KM, Wen X, Aleksunes LM. In Vitro Screening of Environmental Chemicals Identifies Zearalenone as a Novel Substrate of the Placental BCRP/ABCG2 Transporter. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2015;4(3):695–706. doi: 10.1039/C4TX00147H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonker JW, Buitelaar M, Wagenaar E, Van Der Valk MA, Scheffer GL, Scheper RJ, Plosch T, Kuipers F, Elferink RP, Rosing H, et al. The breast cancer resistance protein protects against a major chlorophyll-derived dietary phototoxin and protoporphyria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(24):15649–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202607599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavek P, Merino G, Wagenaar E, Bolscher E, Novotna M, Jonker JW, Schinkel AH. Human breast cancer resistance protein: interactions with steroid drugs, hormones, the dietary carcinogen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo(4,5-b)pyridine, and transport of cimetidine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312(1):144–52. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.073916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gedeon C, Anger G, Piquette-Miller M, Koren G. Breast cancer resistance protein: mediating the trans-placental transfer of glyburide across the human placenta. Placenta. 2008;29(1):39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enokizono J, Kusuhara H, Sugiyama Y. Effect of breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp/Abcg2) on the disposition of phytoestrogens. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72(4):967–75. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.034751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Wang H, Unadkat JD, Mao Q. Breast cancer resistance protein 1 limits fetal distribution of nitrofurantoin in the pregnant mouse. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35(12):2154–8. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.018044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang L, Wang Y, Grimm S. ATP-dependent transport of rosuvastatin in membrane vesicles expressing breast cancer resistance protein. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34(5):738–42. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.007534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou L, Naraharisetti SB, Wang H, Unadkat JD, Hebert MF, Mao Q. The breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp1/Abcg2) limits fetal distribution of glyburide in the pregnant mouse: an Obstetric-Fetal Pharmacology Research Unit Network and University of Washington Specialized Center of Research Study. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73(3):949–59. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.041616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scharenberg CW, Harkey MA, Torok-Storb B. The ABCG2 transporter is an efficient Hoechst 33342 efflux pump and is preferentially expressed by immature human hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 2002;99(2):507–12. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey-Dell KJ, Hassel B, Doyle LA, Ross DD. Promoter characterization and genomic organization of the human breast cancer resistance protein (ATP-binding cassette transporter G2) gene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1520(3):234–41. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evseenko DA, Paxton JW, Keelan JA. ABC drug transporter expression and functional activity in trophoblast-like cell lines and differentiating primary trophoblast. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290(5):R1357–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00630.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bircsak KM, Gupta V, Yuen PY, Gorczyca L, Weinberger BI, Vetrano AM, Aleksunes LM. Genetic and Dietary Regulation of Glyburide Efflux by the Human Placental Breast Cancer Resistance Protein Transporter. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;357(1):103–13. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.230185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pattillo RA, Gey GO. The establishment of a cell line of human hormone-synthesizing trophoblastic cells in vitro. Cancer Res. 1968;28(7):1231–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pattillo RA, Gey GO, Delfs E, Huang WY, Hause L, Garancis DJ, Knoth M, Amatruda J, Bertino J, Friesen HG, et al. The hormone-synthesizing trophoblastic cell in vitro: a model for cancer research and placental hormone synthesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1971;172(10):288–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1971.tb34942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Lee EW, Zhou L, Leung PC, Ross DD, Unadkat JD, Mao Q. Progesterone receptor (PR) isoforms PRA and PRB differentially regulate expression of the breast cancer resistance protein in human placental choriocarcinoma BeWo cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73(3):845–54. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.041087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang H, Zhou L, Gupta A, Vethanayagam RR, Zhang Y, Unadkat JD, Mao Q. Regulation of BCRP/ABCG2 expression by progesterone and 17beta-estradiol in human placental BeWo cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290(5):E798–807. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00397.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szatmari I, Vamosi G, Brazda P, Balint BL, Benko S, Szeles L, Jeney V, Ozvegy-Laczka C, Szanto A, Barta E, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-regulated ABCG2 expression confers cytoprotection to human dendritic cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(33):23812–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604890200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, Koder A, Evans RM. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999;4(4):585–95. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Miki H, Tamemoto H, Yamauchi T, Komeda K, Satoh S, Nakano R, Ishii C, Sugiyama T, et al. PPAR gamma mediates high-fat diet-induced adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance. Mol Cell. 1999;4(4):597–609. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruebner M, Langbein M, Strissel PL, Henke C, Schmidt D, Goecke TW, Faschingbauer F, Schild RL, Beckmann MW, Strick R. Regulation of the human endogenous retroviral Syncytin-1 and cell-cell fusion by the nuclear hormone receptors PPARgamma/RXRalpha in placentogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(7):2383–96. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarrade A, Schoonjans K, Guibourdenche J, Bidart JM, Vidaud M, Auwerx J, Rochette-Egly C, Evain-Brion D. PPAR gamma/RXR alpha heterodimers are involved in human CG beta synthesis and human trophoblast differentiation. Endocrinology. 2001;142(10):4504–14. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tache V, Ciric A, Moretto-Zita M, Li Y, Peng J, Maltepe E, Milstone DS, Parast MM. Hypoxia and trophoblast differentiation: a key role for PPARgamma. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(21):2815–24. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee G, Elwood F, McNally J, Weiszmann J, Lindstrom M, Amaral K, Nakamura M, Miao S, Cao P, Learned RM, et al. T0070907, a selective ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, functions as an antagonist of biochemical and cellular activities. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(22):19649–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kudo Y, Boyd CA, Kimura H, Cook PR, Redman CW, Sargent IL. Quantifying the syncytialisation of human placental trophoblast BeWo cells grown in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1640(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(03)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright JA, Haslam IS, Coleman T, Simmons NL. Breast cancer resistance protein BCRP (ABCG2)-mediated transepithelial nitrofurantoin secretion and its regulation in human intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) layers. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;672(1–3):70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prouillac C, Videmann B, Mazallon M, Lecoeur S. Induction of cells differentiation and ABC transporters expression by a myco-estrogen, zearalenone, in human choriocarcinoma cell line (BeWo) Toxicology. 2009;263(2–3):100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evseenko DA, Paxton JW, Keelan JA. The xenobiotic transporter ABCG2 plays a novel role in differentiation of trophoblast-like BeWo cells. Placenta. 2007;28(Suppl A):S116–20. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uzan J, Carbonnel M, Piconne O, Asmar R, Ayoubi JM. Pre-eclampsia: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011;7:467–74. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S20181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang S, Regnault TR, Barker PL, Botting KJ, McMillen IC, McMillan CM, Roberts CT, Morrison JL. Placental adaptations in growth restriction. Nutrients. 2015;7(1):360–89. doi: 10.3390/nu7010360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jebbink J, Veenboer G, Boussata S, Keijser R, Kremer AE, Elferink RO, van der Post J, Afink G, Ris-Stalpers C. Total bile acids in the maternal and fetal compartment in relation to placental ABCG2 expression in preeclamptic pregnancies complicated by HELLP syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852(1):131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evseenko DA, Murthi P, Paxton JW, Reid G, Emerald BS, Mohankumar KM, Lobie PE, Brennecke SP, Kalionis B, Keelan JA. The ABC transporter BCRP/ABCG2 is a placental survival factor, and its expression is reduced in idiopathic human fetal growth restriction. FASEB J. 2007;21(13):3592–605. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8688com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He P, Chen Z, Sun Q, Li Y, Gu H, Ni X. Reduced expression of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 in preeclamptic placentas is associated with decreased PPARgamma but increased PPARalpha expression. Endocrinology. 2014;155(1):299–309. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holobotovskyy V, Chong YS, Burchell J, He B, Phillips M, Leader L, Murphy TV, Sandow SL, McKitrick DJ, Charles AK, et al. Regulator of G protein signaling 5 is a determinant of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(290):290ra88. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feige JN, Gelman L, Rossi D, Zoete V, Metivier R, Tudor C, Anghel SI, Grosdidier A, Lathion C, Engelborghs Y, et al. The endocrine disruptor monoethyl-hexyl-phthalate is a selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma modulator that promotes adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(26):19152–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hiromori Y, Nishikawa J, Yoshida I, Nagase H, Nakanishi T. Structure-dependent activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma by organotin compounds. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;180(2):238–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Inadera H, Shimomura A. Environmental chemical tributyltin augments adipocyte differentiation. Toxicol Lett. 2005;159(3):226–34. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang M, Webster TF, Ferguson PL, Stapleton HM. Characterizing the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPARgamma) ligand binding potential of several major flame retardants, their metabolites, and chemical mixtures in house dust. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(2):166–72. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fang M, Webster TF, Stapleton HM. Activation of Human Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Nuclear Receptors (PPARgamma1) by Semi-Volatile Compounds (SVOCs) and Chemical Mixtures in Indoor Dust. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49(16):10057–64. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b01523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]