Abstract

Objective

A limited literature suggests an association between parental eating disorders and child eating-disorder behaviors although this research has focused primarily on restrictive-type eating disorders and very little is known about families with binge-eating disorder.

Methods

The current study focused on parents (N=331; 103 fathers and 226 mothers), comparing parents with core features of binge-eating disorder (BED; n=63) to parents with obesity and no eating disorder (OB; n=85) and parents with healthy-weight and no eating disorder (HW; n=183).

Results

Parents with BED were significantly more likely than OB and HW parents to report child binge eating, and more likely than HW parents to report child overeating. Parents with BED felt greater responsibility for child feeding than OB parents, and felt more concern about their child's weight than OB and HW parents. Dietary restriction of the child by the parents was related to child binge eating, overeating, and child overweight, and parental group was related to child binge eating (parental BED), overeating (parental BED) and child weight (parental OB).

Conclusion

Parents with BED report greater disturbance in their children's eating than OB and HW parents, and OB parents report higher child weight than HW parents. This suggests that it is important to consider both eating-disorder psychopathology and obesity in clinical interventions and research. Our cross-sectional findings, which require experimental and prospective confirmations, provide preliminary evidence suggesting potential factors in families with parental BED and obesity to address in treatment and prevention efforts for pediatric eating disorders and obesity.

Keywords: child, binge-eating disorder, fathers, feeding, mothers, obesity, parenting

Binge-eating disorder (BED) is the most common formal eating disorder among adults and adolescents and is associated with obesity and obesity-related health problems (1, 2). Many adults with BED report that family members engaged in binge eating (3, 4), and children appear more likely to have binge/loss-of-control eating if their mothers have binge eating (5). Moreover, behavioral genetics research on binge eating and BED (6) suggests that, similar to anorexia and bulimia nervosa, binge eating is influenced by both environmental and genetics factors (7), with loss of control while eating and distress carrying the highest heritability (8). Yet, despite evidence of a familial association of binge eating, very little is known about parents with BED, their parenting practices, and relations with children's eating behaviors.

Qualitative research suggests that both parents and their children are concerned about children's loss-of-control eating, and parents see a link between their own and their children's eating behaviors (9). Although parents report a strong desire to help their children gain control of their eating, in part due to concerns about potential weight gain, they also report feeling unable and unsure how to improve children's weight and eating behaviors (9). Attempts to help their children can, at times, be misguided and paradoxically exacerbate eating problems and body dissatisfaction, for example, through the use of body-related criticism or focus (9-13). Both the desire to improve parenting practices around healthy eating, and the unintentional exacerbation of eating-disorder psychopathology, can be found in parents with restrictive-type eating disorders (14-16), but have not been well-investigated in parents with BED.

Studies examining the influence of parental BED on children describe adult patients’ recollection of their own childhood experiences with their parents, some of whom also engaged in binge eating (3, 4, 17). Minimal research, however, has generated data regarding BED parents’ reports of their parenting (18, 19) or influences on their children (5, 20), and this research has been with parents of very young children. For example, one study with parents with BED found impaired feeding interactions with their infant children (20). Differences between BED and restrictive-type eating disorders, perhaps most notably the typical low-weight status of patients with restrictive-type eating disorders during childbearing and child rearing stages of life (1), suggest that parents with BED and their children might have distinct experiences from other families with parental eating disorders.

The association between BED and obesity among adults (1) and the wide-spread experiences of weight stigma and mental health stigma among adults with obesity and eating disorders (21) could also influence attitudes about parenting. Therefore, examining parenting practices and concerns among parents with BED, and similarities and differences when compared to parents with obesity and parents with healthy-weight, could help clarify potential associations of parental BED on children's eating behaviors and weight. Initial work suggests that while there is a familial link between parent binge eating and child eating-disorder outcomes, the role of familial obesity is minimal (3, 4, 13, 17, 22, 23).

Children of parents with binge eating show more disordered eating and overeating than children of parents without binge eating (24). Additionally, young children of parents with BED have greater psychopathology in general than children of parents without eating disorders (14, 20). Hypotheses for familial associations include parental modeling of weight and eating behaviors, genetic influences, and parenting practices (7, 16, 25). The parental feeding practice of restriction, which is classified as an “unresponsive” parental feeding practice because it is not in response to child hunger, is associated with higher child weight (26) and children eating in the absence of hunger (25, 27). In one prospective population-based study, mothers with BED reported greater restriction of their children's diet than mothers without eating disorders (19). Moreover, parental binge eating relates specifically to restriction of young children's diet for the purpose of weight control rather than health (18). Existing work on parents with eating disorders, perspectives of adults with BED on the parenting they received, and associations of binge eating with unresponsive parental feeding practices, all suggest that parental BED may play a role in child eating behaviors, but that this role is likely complex due to the relationship of parental BED with obesity, and warrants investigation.

Aim of the current study

The current study sought to examine similarities and differences in child eating behaviors and parental feeding practices among parents meeting core criteria for binge-eating disorder (BED), parents with obesity without an eating disorder (OB), and parents with healthy-weight without an eating disorder (HW). The existing literature on parents with BED is minimal, and uses adult patients’ recollection of their parents during their childhood. The current study examined the parenting practices and child eating behaviors of parents with BED, and used two comparison groups of parents without BED with and without obesity to further clarify the role of parental BED in parenting practices and child eating behaviors. We hypothesized that parents with BED would report more child binge eating than parents with OB and HW. An additional aim was to evaluate “unresponsive” parental feeding practices (i.e., practices not in response to child hunger, including restriction and pressure-to-eat), which have been associated with parent eating-disorder psychopathology (16, 19, 25, 27-29) and child weight (26), and can be conceptualized as learned eating behaviors. We also examined associations among unresponsive feeding practices and child weight and child eating behaviors (i.e., overeating and binge-eating). We hypothesized that unresponsive feeding practices would be greater among parents with BED, and when children had overweight/obesity.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N=331) were recruited from the Mechanical Turk website to complete an online survey on parents’ opinions about weight and eating. Fathers and mothers (recruited from different families) were eligible to participate and included in current analyses. Mechanical Turk provides high-quality and convenient data and yields samples with greater diversity in geography and demographic characteristics than undergraduate samples (30-32). Recent comparisons indicate psychometric properties of measures completed by Mechanical Turk participants do not differ in reliability or validity from participants recruited using traditional sources (31). Mechanical Turk has been used in psychological and psychiatric research (33, 34), including eating research (35). To be eligible to complete the survey, participants had to be at least 21 years old and be primary caregivers for a child 5-15 years old. This study was reviewed and approved by our university's institutional review board; all participants provided informed consent.

Measures

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Parents reported the age, height and weight for their child, which were used to calculate child BMI z-score and child BMI percentile. Parents also reported their own height and weight, which were used to calculate BMI.

Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ)

This measure of parental feeding practices has 31 items rated on five-point scales (26). Items were scored following the model proposed by Anderson and colleagues, which showed superior fit to the original factor structure in diverse community samples (36, 37); higher scores indicate greater levels of each subscale (Perceived Responsibility, Concerns about Child Weight, Restriction, Pressure-to-Eat, Monitoring). Items yielded internally consistent subscale scores in earlier work with parents seeking obesity treatment for their children, α=.65-.91 (37), and the current study, α=.76-.93.

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q)

The EDE-Q retrospectively measures eating-disorder psychopathology over the past 28 days on seven-point scales (38); the current study used a brief version of the full scale, which has been shown to demonstrate superior psychometric properties in nonclinical (39) and clinical (40) studies compared with those from the original measure. Subscales (Restraint, Overvaluation, Dissatisfaction) were internally consistent in earlier work, α=.89-.91 (39), and in the current study α=.90-.94. Items assessing parents’ personal overvaluation by weight and shape were used in scoring algorithms for groups; these items are scored on a 7-point scale from 0=“Not at all,” through 6= “Markedly,” with 4 corresponding to “Moderately.” Behaviors include objective binge-eating episodes (i.e., eating an unusually large amount of food while feeling a sense of loss of control) and objective overeating episodes (i.e., eating an unusually large amount of food without feeling a loss of control) within the past 28 days. Additionally, a parent-report version of the EDE-Q was created by adapting eating-disorder behavioral items to ask about “your child” rather than “you.”

Questionnaire for Eating and Weight Patterns–Revised (QEWP-R)

The QEWP-R, which was used in DSM-IV field trials, retrospectively assesses eating-disorder behaviors and attitudes that align with eating-disorder diagnostic criteria (41). The current study used items from the QEWP-R but changed the binge-eating criterion to weekly over 3 months rather than 6 months to correspond to DSM-5 criteria (42). Frequency items that participants endorse as present are scored on a five-point scale from 1=“Less than once a week” through 5=“More than five times a week,” with 2 corresponding to “Once a week.” Distress items are scored on a five-point scale from 1=“Not at all” through 5=Extremely, with 3 corresponding to “Moderately.”

Algorithms

Scoring algorithms created BED, OB, and HW groups using EDE-Q and QEWP-R items. Parents meeting criteria were identified among a larger sample of parent participants. Parents in the BED group (BED; n=63) endorsed binge-eating episodes (eating an unusually large amount of food and perceiving eating to be out of control) at least weekly over the past three months (QEWP-R item 12, score 2 through 5 accepted), at least moderate distress about overeating (QEWP-R item 15, score 3 through 5 accepted) and loss of control while eating (QEWP-R item 16, score 3 through 5 accepted), and denied weekly inappropriate compensatory behaviors over the past three months (QEWP-R items 18-21, score 1 accepted). Parents in the obesity group (OB; n=85) and healthy-weight group (HW; n=183) denied weekly binge eating (QEWP-R item 12), inappropriate compensatory behaviors (QEWP-R items 18-21), undue influence of weight or shape on self-evaluation (EDE-Q-Brief items 4 or 5, score 0 through 3 accepted), and distress about overeating and loss of control while eating (QEWP-R items 16 and 17). Additionally, parents in the OB group had a body mass index >30 kg/m2, and parents in the HW group had a body mass index 18.5-24.9 kg/m2.

Statistical analyses

To evaluate eating-disorder psychopathology among fathers and mothers endorsing BED, OB, and HW, we compared scores on the EDE-Q brief version using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Chi-square tests evaluated differences in child eating behaviors occurring at least weekly, and MANOVAs evaluated parental feeding practices by parent group. Subsequent analyses examined sex differences within each parent group. Logistic regressions evaluated parent group, unresponsive feeding practices and child eating behaviors and weight in the overall sample.

Results

Comparison of parent groups

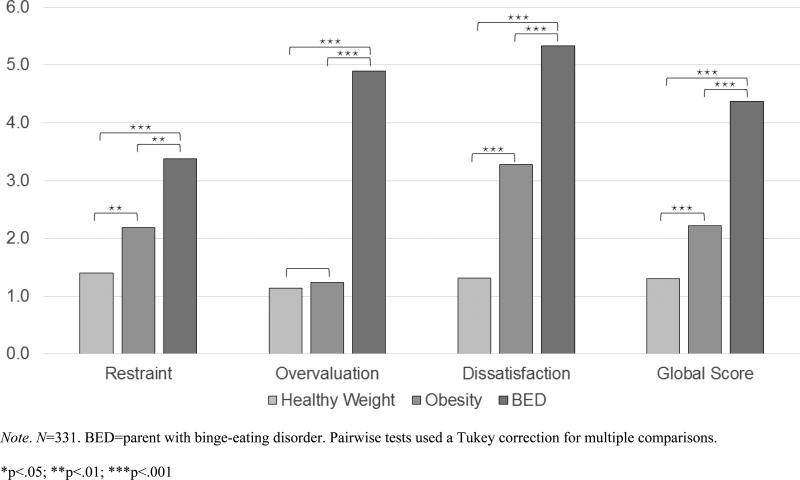

Table 1 shows demographic characteristics and differences among parent groups. EDE-Q subscale scores are presented as support for the scoring algorithms used to create the three study groups and show expected differences among BED, OB and HW groups. MANOVA indicated overall differences in eating-disorder psychopathology by group, Wilks’ λ=0.23, F(6,652)=116.86, p<.001, ηp2=.518. Univariate ANOVAs were also significant for each subscale: Restraint, F(2,328)=23.83, p<.001, ηp2=.127, Overvaluation, F(2,328)=291.75, p<.001, ηp2=.640, Body Dissatisfaction, F(2,328)=236.78, p<.001, ηp2=.591, see Figure 1.

Table 1.

Comparisons of demographic characteristics of parents with BED, Obesity, and Healthy-Weight.

| BED (n=63) | OB (n=85) | HW (n=183) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p | |

| Parent sex | .063 | |||

| Female | 51 (81.0%) | 55 (64.7%) | 120 (65.6%) | |

| Male | 12 (19.0%) | 30 (35.3%) | 61 (33.3%) | |

| Parent race/ethnicity | .066 | |||

| White | 56 (88.9%) | 65 (76.5%) | 143 (78.1%) | |

| Black | 1 (1.6%) | 6 (7.1%) | 11 (6.0%) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (3.2%) | 7 (8.2%) | 7 (3.8%) | |

| Asian | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (1.2%) | 13 (7.1%) | |

| Parent education | .002 | |||

| High school/GED | 12 (19.0%) | 19 (22.4%) | 22 (12.0%) | |

| Some college/Associates | 26 (41.3%) | 41 (48.2%) | 56 (30.6%) | |

| College degree | 18 (28.6%) | 16 (18.8%) | 60 (32.8%) | |

| Post-college | 7 (11.1%) | 8 (9.4%) | 42 (23.0%) | |

| Parent age | M=34.87 (SD=6.81) | M=37.71 (SD=8.18) | M=35.27 (SD=7.88) | .033 |

| Parent BMI | M=35.07 (SD=9.26) | M=36.59 (SD=6.40) | M=21.87 (SD=1.62) | <.001 |

| Child sex | .187 | |||

| Female | 29 (46.8%) | 39 (45.9%) | 101 (56.4%) | |

| Male | 33 (53.2%) | 46 (54.1%) | 78 (43.6%) | |

| Child age | M=9.88 (SD=2.96) | M=10.90 (SD=2.86) | M=10.18 (SD=3.03) | .083 |

| Child weight | ||||

| BMI z-score | M=0.55 (SD=1.53) | M=0.78 (SD=1.39) | M=0.22 (SD=1.43) | .011 |

| BMI percentile | M=65.64 (SD=33.14) | M=71.80 (SD=31.55) | M=56.76 (SD=34.79) | .003 |

| >85th percentile | 25 (39.7%) | 43 (50.6%) | 59 (32.2%) | .014 |

Note. N=331. Significance values are from chi-square tests (categorical) or analyses of variance (continuous). The range of parent BMIs by group were: BED 19.6-64.5 kg/m2, OB 30.1-73.2 kg/m2, HW 18.6-25.0 kg/m2).

Figure 1.

Mean differences in eating-disorder psychopathology among parents with healthy weight, obesity, or BED.

Child eating behaviors

Chi-square tests compared weekly child eating behaviors (objective overeating episodes and objective binge-eating episodes). BED parents were significantly more likely than OB and HW parents to report child binge-eating, and significantly more likely than HW parents to report child overeating (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Chi-square comparisons of frequencies of child eating- and weight-related behaviors across parent HW, OB, and BED groups.

| BED (n=63) | OB (n=85) | HW (n=183) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Eating Behaviors | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | χ 2 | p | φ |

| Overeating episodes | 16 (25.4%)† | 13 (15.3%) | 23 (12.6%)* | 5.84 | .054 | .133 |

| Binge-eating episodes | 13 (20.6%)†‡ | 4 (4.7%)* | 9 (4.9%)* | 17.56 | <.001 | .230 |

Note. N=331. Frequencies represent the parent-reported child behavior at least weekly over the past month. BED=parent with binge-eating disorder, OB=parent with obesity, HW=parent with healthy-weight

significantly different from BED parents at p<.05

significantly different from HW parents at p<.05

significantly different from OB parents at p<.05

Parental feeding practices

Table 3 shows mean scores for parental feeding practices. MANOVA revealed a difference between BED, OB, and HW parents for feeding practices, Wilks’ λ=0.905, F(10,636)=3.27, p<.001, ηp2=.049. Univariate subscale results indicated parent group differences in perceived responsibility and concern about child weight. Post-hoc comparisons using a Tukey correction for multiple comparisons found that BED parents perceived greater feeding responsibility than OB parents (p=.02), and BED parents had greater concern about their child's weight than OB (p=.010) and HW (p=.001) parents. A subsequent MANOVA that also included parent sex revealed an interaction of parent group by parent sex only for perceived responsibility over feeding, F(2,322)=5.12, p=.006, ηp2=.031; there were no other interaction or main effects of sex on parent feeding variables.

Table 3.

Mean differences in parental feeding practices and child weight by parent group.

| BED Father (n=12) | BED Mother (n=51) | OB Father (n=30) | OB Mother (n=55) | HW Father (n=61) | HW Mother (n=121) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Feeding | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | F | Total df | p | η p 2 |

| Perceived Responsibility | 4.42 (0.74) | 4.20 (0.83) | 3.29 (0.90) | 4.13 (0.72) | 3.66 (0.94) | 4.16 (0.88) | 3.69 | 329 | .026 | .022 |

| Concern about Child Weight | 2.58 (1.75) | 2.08 (1.29) | 1.52 (0.77) | 1.72 (10.2) | 1.64 (1.07) | 1.55 (0.98) | 7.32 | 329 | .001 | .043 |

| Restriction | 3.72 (0.80) | 3.51 (1.39) | 3.23 (1.05) | 3.30 (1.37) | 3.36 (1.33) | 3.37 (1.21) | 0.89 | 329 | .412 | .005 |

| Pressure-to-Eat | 2.56 (0.75) | 2.46 (1.11) | 2.46 (1.22) | 2.23 (1.32) | 2.80 (0.94) | 2.46 (1.15) | 1.58 | 329 | .208 | .010 |

| Monitoring | 3.44 (1.10) | 3.48 (1.14) | 3.01 (1.24) | 3.32 (1.15) | 3.05 (1.24) | 3.24 (1.15) | 1.57 | 329 | .210 | .010 |

| Child BMI z-score | −0.03 (2.29) | 0.68 (1.31) | 0.68 (1.50) | 0.84 (1.34) | 0.54 (1.37) | 0.06 (1.44) | 4.53 | 322 | .011 | .028 |

Note. N=331. ANOVA results and mean scores and standard deviations on subscales of the Child Feeding Questionnaire by parent group and parent sex. ANOVAs evaluated differences across parent groups (BED, OB, and HW). BED=parent with binge-eating disorder, OB=parent with obesity, HW=parent with healthy-weight

Multivariate logistic regressions evaluated the role of unresponsive feeding practices (restriction and pressure-to-eat) and parent group (BED, OB, HW) in child eating behaviors (see Table 4). BED group membership and restriction were significantly associated with binge eating. BED group membership, restriction and pressure-to-eat were significantly associated with overeating.

Table 4.

Logistic regressions examining associations among unresponsive feeding practices, child overweight, and child eating behaviors in children of HW, OB, and BED parents.

| Multivariate Logistic Regression: Unresponsive Feeding Practices and Parent Group | IV: BED group membership | IV: OB group membership | IV: Restriction | IV: Pressure-to-eat | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ 2 | df | p | Nagelkerke R2 | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Child Overeating | 25.23 | 4 | <.001 | .126 | 2.19* (1.04-4.61) | 1.15 (0.54-2.48) | 1.63** (1.23-2.15) | 0.65** (0.48-0.88) |

| Child Binge-eating | 27.84 | 4 | <.001 | .191 | 4.64** (1.82-11.82) | 0.93 (0.27-3.19) | 2.07** (1.31-3.27) | 0.81 (0.54-1.20) |

| Child Overweight/Obesity | 25.95 | 4 | <.001 | .105 | 1.30 (0.70-2.40) | 2.21** (1.27-3.84) | 1.43*** (1.18-1.74) | 0.78* (0.63-0.97) |

Note. N=331. Logistic regression models used all BED, OB, and HW parents. Significant odds ratios (*p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001) greater than 1 indicate increased likelihood of child eating behavior/weight; odds ratios between 0 and 1 indicate decreased likelihood of child eating behavior/weight.

Child weight

Child BMI z-scores were significantly different across parent groups, F(2,322)=4.53, p=.011, ηp2=.028. Post-hoc comparisons using a Tukey correction for multiple comparisons found that the children of OB parents had higher child BMI z-scores than children of HW parents (p=.011), but no other pairwise comparisons were significant. A subsequent ANOVA that included parent sex revealed a significant interaction of parent group and parent sex for child BMI z-score, F(2, 322)=3.18, p=.043, ηp2=.020. There was no main effect of parent sex. Post-hoc comparisons using a Tukey correction found that child BMI z-scores were higher for OB mothers than HW mothers (p=.01), but no other comparisons were significant.

Multivariate logistic regressions next evaluated the role of unresponsive feeding practices (restriction and pressure-to-eat) and parent group (BED, OB, HW) in child weight. OB group membership, restriction and pressure-to-eat were significantly associated with child overweight/obesity (see Table 4).

In parallel analyses for parental feeding practices and for child weight, our findings remained largely unchanged even when including parent weight, child weight, child age, and child sex as covariates (data not shown).

Discussion

Analyses of child eating behaviors, parental feeding practices and child weight provide evidence of a link between child and parent binge eating, and to a lesser extent, overeating. This is an important finding because it speaks to potential familial influences on the development of child binge eating. Parents with BED reported feeling greater responsibility for their children's feeding than OB parents, and greater concern about their child's weight than OB and HW parents, even though the children of parents with BED were not significantly heavier than the children of parents with obesity or healthy-weight. The pattern of associations for binge eating and obesity suggests the necessity of differentiating between BED and obesity in parents when considering their effects on children.

Our findings that parents with BED reported more child eating-disorder behaviors are consistent with previous research examining parents with restrictive-type eating disorders (24, 43, 44), as is the greater concern parents with BED feel about their children's about child weight (14, 45) than parents without eating-disorder psychopathology. Parent and child binge eating within families extends earlier work with adults with BED (3, 4, 17, 22). Prospective and experimental studies are needed to confirm and extend the associations found in the current study, as has been done with the children of mothers with other eating disorders (e.g., 14, 43, 44, 46).

Research has been limited, predominantly, to mothers with restrictive-type eating disorders and the perspectives of patients with BED about their parents during childhood. The current study extends this earlier work by comparing parents with core features of BED to parents with obesity and parents with neither BED nor obesity. Although the BED study group cannot be considered to have a formal clinical diagnosis as it was not determined in the context of a clinical diagnostic interview, we used scoring algorithms on data generated from psychometrically-established measures to categorize parents who endorsed current BED psychopathology to approximate the clinical diagnosis. The similarity between our findings and those using adult clinical BED samples of participants (3, 4, 17, 22), and large community samples (23, 24), suggests a consistency that warrants further experimental investigation. Furthermore, associations among parental binge eating, restrictive parental feeding practices and child weight, suggest that interventions focusing on parental feeding practices might improve pediatric obesity. In addition to the potential modeling or transmission of eating-disorder behaviors to youth, parental binge eating and obesity have treatment implications for youth, as they are associated with attrition from pediatric obesity treatment (47, 48). This, taken together with parents’ misguided attempts to improve weight and control over eating through weight-criticism and focus on weight (9-13), suggests the merits of co-occurring parent and child treatment, or family treatment, to improve outcomes.

Extant studies have shown a relation between unresponsive parental feeding practices (pressure-to-eat and restriction) and child eating-disorder behaviors (25, 27, 49), and child weight (26). Our findings that binge-eating, overeating, and child weight were related to restriction fits within the context of this earlier work. Moreover, our findings that parental BED was related to child binge eating and overeating but not child weight or other eating behaviors, help clarify the role of parental BED. This further suggests the need to consider parental BED and obesity as independent, yet related, factors in child eating behaviors. The non-significantly higher restriction among parents with BED than OB and HW suggests that earlier work showing greater restriction of children's diet among parents with BED (18, 19) may have been measuring a distinct construct, such as restriction with a specific purpose such as weight control (18); this warrants further clarification and investigation.

Results of the current study should be interpreted within the context of the study's limitations, including the cross-sectional design, which precludes conclusions about causation. It is possible that in the current study, differences between BED, OB, and HW parents in child binge eating were due to BED parents’ increased perception of binge-eating behavior, rather than transmission of BED psychopathology. Use of multiple sources of information about eating behaviors, including child interviews and co-caregiver or teacher report, could clarify these potential explanations to enhance understanding of causes of pediatric eating disorders and obesity. There is also potential subjectivity bias in self-reported and parent-reported measures. Measures relying on self-reported and parent-reported responses could have the benefit of eliciting more honest disclosure of sensitive or shame-inducing information, such as eating behaviors and attitudes (38), than data gathered by face-to-face interview, but survey responses are still susceptible to the influence of social desirability. In psychometric studies of binge-eating assessment, parent-reported binge-eating episodes have acceptable agreement with child-reported and interview measures of binge-eating episodes (50-52). Parent-reported data have a similar pattern and magnitude of agreement compared with adults’ self-reported versus interview assessment (53), yet it is important to note that as with adults, parents were better at knowing when binge eating was not occurring than when it was occurring, and better at identifying children's distress and body dissatisfaction than frequencies of eating-disorder behaviors (50-52). Parents also reported their height and weight, and those of their child. Earlier work has shown that discrepancies between self-reported and measured weights among adult patients were not related to eating-disorder psychopathology (54), but associations of psychopathology with discrepancies between parent-reported weights and measured child weights have not been studied. Measurement of child weight and observation of child eating-disorder psychopathology, or use of corroborative interviews, could clarify these potential areas of bias. Questionnaires are also susceptible to inattention; however, the online platform used for parent recruitment in the current study, Mechanical Turk, provides high-quality data from diverse, internally-motivated participants and allows for the inclusion of items designed to evaluate participants’ attention (30). Mechanical Turk has been used in psychological and psychiatric research (33, 34) and eating research (35).

Despite these limitations, the current study had noteworthy strengths: inclusion of fathers in BED, OB and HW groups (in addition to mothers), focus on BED with obesity and healthy weight comparison groups, use of a community sample (i.e., lessening treatment-seeking confounds), and examination of both parental feeding practices and child eating behaviors. Eating disorders have complex etiology including genetic influences, environmental influences, and psychosocial learning processes (16, 55). The associations found in the current study provide initial evidence that children of parents with BED may be at increased risk for engaging in certain eating behaviors (binge eating and, to a lesser extent, overeating), and thus represent a group that could benefit from targeted prevention programs. Future research on this clinical need, including secondary prevention programs and augmentation of clinical treatments for parental and pediatric BED and obesity, is needed to improve the health of patients and their children.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health grant K24 DK070052 (Dr. Grilo).

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, Merikangas KR. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:714–23. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowler SJ, Bulik CM. Family environment and psychiatric history in women with binge- eating disorder and obese controls. Behav Change. 1997;14:106–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudson JI, Lalonde JK, Berry JM, Pindyck LJ, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, et al. Binge-eating disorder as a distinct familial phenotype in obese individuals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:313–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zocca JM, Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Columbo KM, Raciti GR, Brady SM, et al. Links between mothers' and children's disinhibited eating and children's adiposity. Appetite. 2011;56(2):324–31. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Javaras KN, Laird NM, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Bulik CM, Pope HG, Jr., Hudson JI. Familiality and heritability of binge eating disorder: results of a case-control family study and a twin study. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41(2):174–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.20484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Bulik CM, Tambs K, Harris JR. Genetic and environmental influences on binge eating in the absence of compensatory behaviors: a population-based twin study. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;36:307–14. doi: 10.1002/eat.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell KS, Neale MC, Bulik CM, Aggen SH, Kendler KS, Mazzeo SE. Binge eating disorder: a symptom-level investigation of genetic and environmental influences on liability. Psychol Med. 2010;40(11):1899–906. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmberg AA, Stern M, Kelly NR, Bulik C, Belgrave FZ, Trapp SK, et al. Adolescent girls and their mothers talk about experiences of binge and loss of control eating. J Child Fam Stud. 2014;23:1403–16. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9797-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berge JM, Maclehose R, Loth KA, Eisenberg M, Bucchianeri MM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Parent conversations about healthful eating and weight: Associations with adolescent disordered eating behaviors. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:746–53. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartmann AS, Czaja J, Rief W, Hilbert A. Psychosocial risk factors of loss of control eating in primary school children: A retrospective case-control study. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:751–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.22018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumark-Sztainer D, Bauer KW, Friend S, Hannan PJ, Story M, Berge JM. Family weight talk and dieting: How much do they matter for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors in adolescent girls? J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:270–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saltzman JA, Liechty JM. Family correlates of childhood binge eating: A systematic review. Eat Behav. 2016;22:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agras S, Hammer L, McNicholas F. A prospective study of the influence of eating- disordered mothers on their children. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25:253–62. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199904)25:3<253::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bryant-Waugh R, Turner H, East P, Gamble C. Developing a parenting skills-and- support intervention for mothers with eating disorders and pre-school children Part 1: Qualitative investigation of issues to include. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15:350–6. doi: 10.1002/erv.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazzeo SE, Zucker NL, Gerke CK, Mitchell KS, Bulik CM. Parenting concerns of women with histories of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:77–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Striegel-Moore RH, Fairburn CG, Wilfley DE, Pike KM, Dohm FA, Kraemer HC. Toward an understanding of risk factors for binge-eating disorder in black and white women: A community-based case-control study. Psychol Med. 2005;35:907–17. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saltzman JA, Liechty JM, Bost KK, Fiese BH. Parent binge eating and restrictive feeding practices: Indirect effects of parent's responses to child's negative emotion. Eat Behav. 2016;21:150–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reba-Harrelson L, Von Holle A, Hamer RM, Torgersen L, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Bulik CM. Patterns of maternal feeding and child eating associated with eating disorders in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Eat Behav. 2010;11:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cimino S, Cerniglia L, Porreca A, Simonelli A, Ronconi L, Ballarotto G. Mothers and fathers with binge eating disorder and their 18-36 months old children: A longitudinal study on parent-infant interactions and offspring's emotional-behavioral profiles. Front Psychol. 2016;7:580. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puhl R, Suh Y. Stigma and eating and weight disorders. Current psychiatry reports. 2015;17:552–61. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brody ML, Walsh BT, Devlin MJ. Binge eating disorder: Reliability and validity of a new diagnostic category. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:381–6. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamerz A, Kuepper-Nybelen J, Bruning N, Wehle C, Trost-Brinkhues G, Brenner H, et al. Prevalence of obesity, binge eating, and night eating in a cross-sectional field survey of 6-year-old children and their parents in a German urban population. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:385–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldschmidt AB, Wall MM, Choo TH, Bruening M, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Examining associations between adolescent binge eating and binge eating in parents and friends. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:325–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.22192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birch LL, Fisher JO, Davison KK. Learning to overeat: Maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls' eating in the absence of hunger. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:215–20. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birch LL, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, Markey CN, Sawyer R, Johnson SL. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: A measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite. 2001;36:201–10. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonneville KR, Rifas-Shiman SL, Haines J, Gortmaker S, Mitchell KF, Gillman MW, Taveras EM. Associations of parental control of feeding with eating in the absence of hunger and food sneaking, hiding, and hoarding. Child Obes. 2013;9:346–9. doi: 10.1089/chi.2012.0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell GF, Treasure J, Eisler I. Mothers with anorexia nervosa who underfeed their children: Their recognition and management. Psychol Med. 1998;28:93–108. doi: 10.1017/s003329179700603x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blissett J, Haycraft E. Parental eating disorder symptoms and observations of mealtime interactions with children. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70:368–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon's Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Behrend TS, Sharek DJ, Meade AW, Wiebe EN. The viability of crowdsourcing for survey research. Behav Res Methods. 2011;43:800–13. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hauser DJ, Schwarz N. Attentive Turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than do subject pool participants. Behav Res Methods. 2016;48:400–7. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0578-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sznycer D, Tooby J, Cosmides L, Porat R, Shalvi S, Halperin E. Shame closely tracks the threat of devaluation by others, even across cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:2625–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514699113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisenbarth H, Lilienfeld SO, Yarkoni T. Using a genetic algorithm to abbreviate the Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised (PPI-R). Psychol Assess. 2015;27:194–202. doi: 10.1037/pas0000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollert GA, Kauffman AA, Veilleux JC. Symptoms of psychopathology within groups of eating-disordered, restrained eating, and unrestrained eating individuals. J Clin Psychol. 2016;72:621–32. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson CB, Hughes SO, Fisher JO, Nicklas TA. Cross-cultural equivalence of feeding beliefs and practices: The psychometric properties of the child feeding questionnaire among Blacks and Hispanics. Prev Med. 2005;41:521–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lydecker JA, Simpson C, Kwitowski M, Gow RW, Stern M, Bulik CM, Mazzeo SE. Evaluation of parent-reported feeding practices in a racially diverse, treatment-seeking child overweight/obesity sample. Child Health Care. 2016 doi: 10.1080/02739615.2016.1163489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:363–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grilo CM, Reas DL, Hopwood CJ, Crosby RD. Factor structure and construct validity of the eating disorder examination-questionnaire in college students: Further support for a modified brief version. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:284–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.22358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grilo CM, Crosby RD, Peterson CB, Masheb RM, White MA, Crow SJ, et al. Factor structure of the eating disorder examination interview in patients with binge-eating disorder. Obesity. 2010;18:977–81. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yanovski SZ. Binge eating disorder: Current knowledge and future directions. Obes Res. 1993;1:306–24. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1993.tb00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Easter A, Naumann U, Northstone K, Schmidt U, Treasure J, Micali N. A longitudinal investigation of nutrition and dietary patterns in children of mothers with eating disorders. J Pediatr. 2013;163:173–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.11.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stein A, Woolley H, Cooper S, Winterbottom J, Fairburn CG, Cortina-Borja M. Eating habits and attitudes among 10-year-old children of mothers with eating disorders: Longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:324–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.014316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sadeh-Sharvit S, Levy-Shiff R, Feldman T, Ram A, Gur E, Zubery E, et al. Child feeding perceptions among mothers with eating disorders. Appetite. 2015;95:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bryant-Waugh R, Turner H, Jones C, Gamble C. Developing a parenting skills-and- support intervention for mothers with eating disorders and pre-school children Part 2: Piloting a group intervention. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15:439–48. doi: 10.1002/erv.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braden AL, Madowitz J, Matheson BE, Bergmann K, Crow SJ, Boutelle KN. Parent binge eating and depressive symptoms as predictors of attrition in a family-based treatment for pediatric obesity. Child Obes. 2015;11:165–9. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jelalian E, Hart CN, Mehlenbeck RS, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Kaplan JD, Flynn-O'Brien KT, Wing RR. Predictors of attrition and weight loss in an adolescent weight control program. Obesity. 2008;16:1318–23. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loth KA, MacLehose RF, Fulkerson JA, Crow S, Neumark-Sztainer D. Are food restriction and pressure-to-eat parenting practices associated with adolescent disordered eating behaviors? Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:310–4. doi: 10.1002/eat.22189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elliott CA, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Mirza NM. Parent report of binge eating in Hispanic, African American and Caucasian youth. Eat Behav. 2013;14:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Comparison of child interview and parent reports of children's eating disordered behaviors. Eat Behav. 2005;6:95–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson WG, Grieve FG, Adams CD, Sandy J. Measuring binge eating in adolescents: Adolescent and parent versions of the questionnaire of eating and weight patterns. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;26:301–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199911)26:3<301::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berg KC, Stiles-Shields EC, Swanson SA, Peterson CB, Lebow J, Le Grange D. Diagnostic concordance of the interview and questionnaire versions of the Eating Disorder Examination. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:850–5. doi: 10.1002/eat.20948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White MA, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Accuracy of self-reported weight and height in binge eating disorder: misreport is not related to psychological factors. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(6):1266–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Waugh E, Bulik CM. Offspring of women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25:123–33. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199903)25:2<123::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]