Abstract

Primary colonic-type adenocarcinoma involving the tongue (CTAT) is exquisitely rare, with only four cases having been reported in the literature. We report the case of a 53-year-old woman with an anterior (oral) tongue mass. A review of literature was performed. Histomorphologic features were evaluated with standard hematoxylin and eosin stained sections. Ancillary testing was performed. The mass consisted of invasive adenocarcinoma associated with “dirty necrosis”, akin to the phenotype seen in colorectal adenocarcinoma. By immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells were positive for AE1/3, CDX2, CK20, SATB2 and beta-catenin. This was initially felt to represent a metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma but subsequent PET/CT and colonoscopy examination were negative for colorectal mass, excluding the possibility of a metastasis and confirming a diagnosis of CTAT. We raise awareness of the existence of this entity and recommend that metastatic disease be excluded before rendering a diagnosis of CTAT.

Keywords: Oral tongue, Adenocarcinoma, Colonic-type

Introduction

Primary lingual adenocarcinomas, thought to arise from minor salivary glands, are exceedingly rare neoplasms [1]. Of 542 intraoral tumors examined by Pires et al. [2] 21 (3.9 %) arose from the floor of the mouth and of those, only 3 (0.5 %) were pure adenocarcinoma. Although conventional salivary gland adenocarcinomas may arise, the primary colonic-type adenocarcinoma (CTAT) variant, involving the tongue is exquisitely rare, with now five cases being reported in the literature [3–5]. All cases involved the tongue and shared similar histomorphology and immunophenotype. Herein, we report another rare occurrence of primary colonic-type adenocarcinoma involving the anterior (oral) tongue.

Case Report

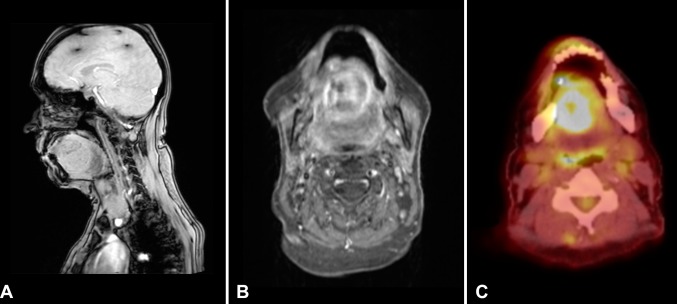

The patient was a 53 year old female with past medical history significant for hypercalcemia secondary to hyperparathyroidism, ethanol abuse and both tobacco and extensive marijuana use. The patient had reportedly ceased cigarette usage approximately 6 months prior to her presentation. No history of wood dust exposure was noted. Her family history was significant for renal cell carcinoma in her grandmother. She presented with a 3 month history of edema and discomfort of the left lateral aspect of the tongue, accompanied by progressive dysphagia and dysphonia. The patient also complained of intermittent left otalgia and a 20-pound weight loss during the prior 3 months. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck identified a partially cystic mass involving the oral tongue and sublingual floor of mouth (Fig. 1). The patient was taken to the operating room for incision and drainage and aspiration of the cyst at an outside hospital. Cytopathology of the cyst aspirate demonstrated adenocarcinoma. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET–CT) of the mass showed intense hypermetabolic activity. Additionally, two hypermetabolic level IIA lymph nodes were identified. The sinonasal cavity and paranasal sinuses were unremarkable. No other suspicious foci were identified in the body on PET–CT. An anterior glossectomy with bilateral selective neck dissection and radial free flap reconstruction was performed. Post-operative external-beam radiation therapy was administered to the tumor bed. The patient is now 1 year post-resection with no clinical or radiologic evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease.

Fig. 1.

Imaging of base of tongue mass. a Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing a rounded hyperdense mass arising within the anterior (oral) tongue musculature; b axial MRI demonstrating the same mass as confined to the tongue and; c PET–CT showing hypermetabolic activity within the tumor

Methods

All surgical specimens were fixed in 10 % formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned (4 µm) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A panel of immunohistochemical stains was performed on the formalin fixed paraffin embedded sections from resection specimen, using commercially available antibodies. The antibodies, their clones, dilutions, sources which were used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of antibodies used including sources and dilution

| Antibody | Type | Dilution | Sourcea |

|---|---|---|---|

| AE1/3 | Mouse monoclonal | 1:300 | Dako |

| CK20 | Mouse monoclonal | 1:200 | Dako |

| CK7 | Mouse monoclonal | 1:600 | Dako |

| CDX2 | Mouse monoclonal | 1:300 | Biogenex |

| Beta-catenin | Mouse monoclonal | 1:400 | Dako |

| SATB2 | Mouse monoclonal | 1:500 | Santa Cruz |

| MLH1 | Mouse monoclonal | 1:200 | Novocastra |

| MSH2 | Mouse monoclonal | 1:100 | Calbiochem |

| MSH6 | Rabbit monoclonal | 1:200 | Epitomics |

| PMS2 | Mouse monoclonal | 1:200 | BD Biosciences |

aDako North America Inc., Carpinteria, CA, USA; Novocastra by Leica Biosystems, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA; Epitomics by Abcam, Cambridge, UK; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA; Biogenex, Fremont, CA, USA; Calbiochem by Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany

Results

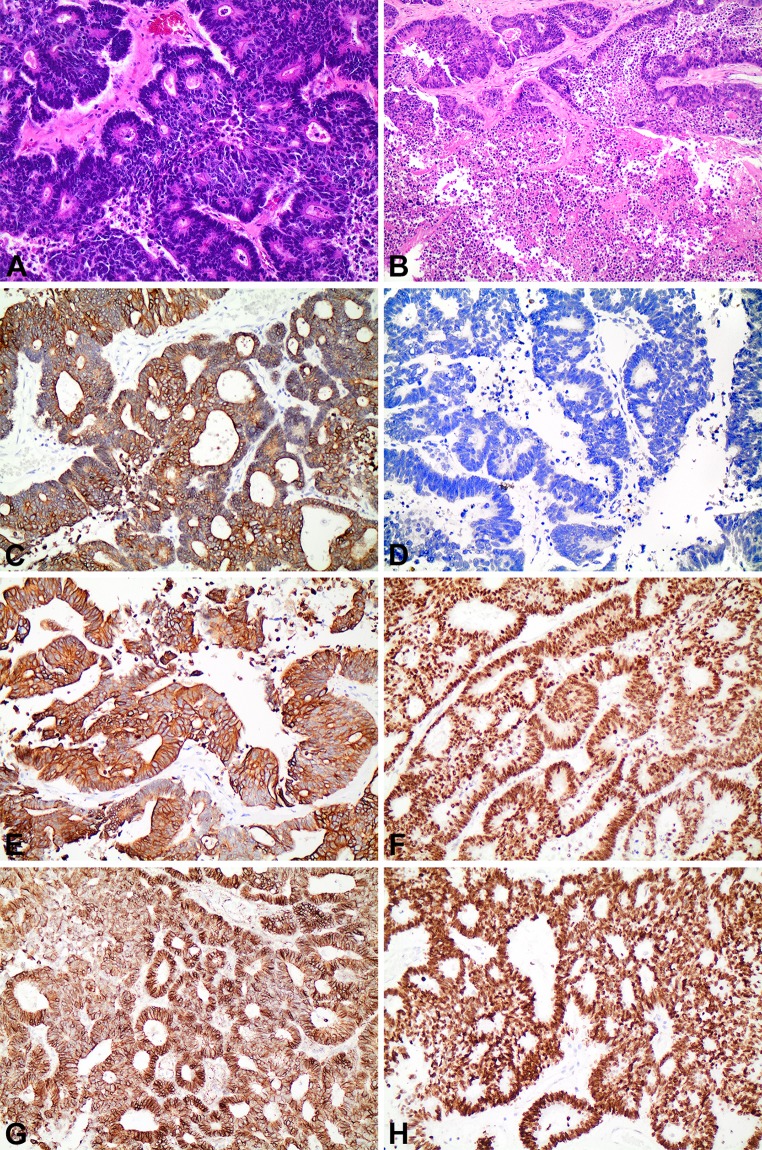

Grossly, the resection specimen consisted of a portion of tongue exhibiting a 3.6 × 3.3 × 3.0 cm grey-white, well-circumscribed mass abutting the ventral surface. Histologically, the mass consisted of invasive adenocarcinoma demonstrating a papillary, tubulo-glandular pattern, associated with “dirty necrosis,” akin to the phenotype seen in primary colorectal adenocarcinoma. The overlying squamous mucosa was unremarkable and showed no evidence of dysplasia. Examination of the 61 cervical lymph nodes was negative for metastatic disease. By immunohistochemistry, the tumoral cells were positive for pancytokeratin AE1/3 (moderate, diffuse), CK20 (strong), CDX2, SATB2 (strong) and beta-catenin (cytoplasmic) and negative for CK 7 in the majority of cells. Microsatellite markers (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, MSH6) were all intact (Fig. 2). Based on the histomorphology and immunophenotype, an initial diagnosis of metastatic adenocarcinoma of colorectal origin was rendered. However, subsequent imaging studies including colonoscopy and PET/CT scan studies were negative for malignancy in the gastrointestinal tract, clinically excluding a colorectal origin.

Fig. 2.

Histomorphology and immunophenotype of CTAT. a Hematoxylin and Eosin (×mag. 200) showing tumor foci exhibiting a papillary and glandular architecture, focally cribiforming. b Hematoxylin and Eosin (×mag. 100) showing confluent intraluminal “dirty” necrosis within tumoral glands. c (×Mag. 200): moderate, diffuse expression of pancytokeratin AE1/3. d (×Mag. 200): negative expression of CK7. e (×Mag. 200): strong diffuse expression of CK20. f (×Mag. 200): strong and diffuse nuclear expression of CDX2. g (×Mag. 200): strong cytoplasmic expression of beta-catenin. h (×Mag. 200): strong expression of SATB2

Discussion

Lingual adenocarcinomas, both primary and metastatic alike are exquisitely rare events. The distribution of lesions reported thus far demonstrate are nearly evenly divided with three cases involving the base of tongue and two cases involving the anterior (oral) tongue. (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of previously reported cases of CTAT

| References | Age/gender | Anatomic location | IHC | Metastasis status | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bell et al. [3] | 58 M | Base of tongue | (+): CK20, CDX2, beta-catenin, CK7 (focal), MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 | Positive—1 lymph node | Surgery | No evidence of recurrence (13 months) |

| 58 M | Base of tongue | (+): CK20, CDX2, beta-catenin, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 | Positive—bilateral lung nodules, multiple lymph nodes | Chemotherapy + surgery | No evidence of recurrence (11 months) | |

| (−): CK7 | ||||||

| Slova et al. [4] | 49 M | Base of tongue | (+): AE1/3, CK20, CK7, CAM5.2, CDX2, villin, EMA, p16, CEA | Positive—4/64 lymph nodes | Surgery + adjuvant radiation | |

| McDaniel et al. [5] | 60 M | Anterior tongue | (+): CDX2, CK7, CK20 | Positive—bilateral cervical lymph nodes | Surgery + adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation | Recurrence of disease as lung metastases (14 months postoperative); DOD 5 years postoperation |

| (−): TTF-1 | ||||||

| Smith et al. (present case) | 53 F | Anterior (Oral) tongue | (+): AE1/3, CK20, CDX2, SATB2, beta-catenin, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 | Negative | Surgery + adjuvant radiation | No evidence of recurrence or metastasis (8 months) |

| (−): CK7 |

Morphologically, CTAT are characterized by well- to moderately-differentiated intestinal-type adenocarcinoma. Features of intestinal-type adenocarcinoma, including “dirty” necrosis (necrotic debris within the glandular lumina), intra- and extracellular mucin production, pushing-borders with desmoplastic reaction are frequently present. Cytologic features may be low- or high grade, but in reported cases have shown prominent nucleoli, increased nucleus to cytoplasmic ratio, and loss of nuclear polarity. Documented cases have appeared as exophytic masses invading into the deep muscles of the tongue. Immunohistochemically, these tumors are identical to colorectal carcinoma, showing CDX2 and CD20 expression with variable CK7 expression.

Bell et al. [3] documented the first two cases of sublingual colonic-type adenocarcinoma. Both cases arose in patients in their sixth decade of life, each with a past medical history of tobacco use. The masses measured 3.0 and 4.5 cm in greatest dimension, both extending from the base of the tongue to the superficial mucosa. Lymph node metastases were noted in both cases. Microscopically, both tumors consisted of well- to moderately-differentiated colonic adenocarcinoma, similar to that seen in our case. Immunohistochemistry also demonstrated a similar profile to the tumor seen in our case, wherein both tumors demonstrated strong positive membranous/cytoplasmic staining for CK20 and beta-catenin, and nuclear staining for CDX2. CK7 staining was negative in one of the tumors and focally positive in the other. Of note, follow-up of at least 11 months in both cases following surgical resection demonstrated no evidence of recurrent disease.

In their 2012 report, Slova et al. document a similar appearing lingual mass arising in a 49 year-old patient with over 20 years of occupational exposure to wood-dust, akin to that which is seen in the sinonasal tract intestinal-type adenocarcinomas [4, 6]. The 3.6 cm tumor was infiltrative and demonstrated marked mucinous (colloid) features among intestinal-type adenocarcinoma. Again, lymph node metastases were present. Lesional cells expressed AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, CK7, CK20, CDX-2, villin, p16, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA).

Several theories have been proposed to explain the bizarre histogenetic nature of this neoplasm. Slova et al. [4] suggested malignant transformation of a minor salivary gland may result in adenocarcinoma of the oral cavity—and when occurring in the base of the tongue, may result in CTAT. Yet, alone, this theory does not fully explain why transformation into colonic-type adenocarcinoma—opposed to conventional adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands—occurs. Secondly, the unusual location of a glandular neoplasm in the belly of a muscle raises the question of embryological rest involvement. In a theory dating back to the times of Virchow [7], adult tissues may harbor embryonic remnants that normally lie dormant but can be “activated” to become malignant [8]. The crux of this theory relies on the notion that stem cells within these rests accumulate mutations which lead to cellular immortality, rather than the malignant degeneration of a differentiated cell. We note that the opportunity for such transformation is present, as several studies have noted the presence of stem/progenitor cells in the base of the tongue [9].

Our case mirrors closely the previously reported cases in that exposure to environmental toxins for at least a decade was present. Interestingly, in addition to tobacco usage, our patient had a longstanding history of smoking marijuana on a near-daily basis. The effects of cannabis usage in carcinogenesis (if any) are still being delineated, however a recent publication has shown compelling evidence that alterations in molecular signaling—particularly in the EGFR pathway—may increase the risk of development of laryngeal carcinoma [10].

Presently, the direct cause of CTAT is unknown. Of the five cases in the literature, all have documented environmental exposures to tobacco or wood-dust (Table 2). The correlation of wood dust particle exposure with intestinal-type sinonasal adenocarcinoma (ITAC) has been well-documented [6]. Interestingly, analysis of ITAC mutations has identified TP53 mutations in approximately 40 % of ITAC [11]. Of these, the mutation in the TP53 suppressor gene demonstrated a characteristic—though neither specific nor exclusive—G→A transition in codons 248, 176 or 175. Consequently, investigations into K-ras and BRAF mutations in ITAC has suggested little involvement of these genes in the etiology (therefore limiting their use in predicting response to EGFR-inhibitors, as used in hereditary colorectal carcinomas) [12]. To that end, evaluation of K-ras in CTAT in one case has been found to be negative [3]. Bell et al. documented intact MMR in their cases of CTAT [2]. Our case also shows intact MMR, suggesting that CTAT is not likely related to a familial/inherited mutation.

The principal differential diagnosis of metastatic colorectal carcinoma must be addressed, considering that the immunoprofile of colonic adenocarcinoma is identical to that presently found in this case. In the present case, a colonoscopy was undertaken and found only a serrated polyp with features of hyperplastic polyp and sessile serrated adenoma. Metastatic disease to the oral cavity is an uncommon occurrence. In a study of 1455 oropharyngeal malignancies, 2.0 % were metastatic disease and of those, only 2 (0.01 %) were of colorectal origin [13]. Among the 218 cases of oral mucosal metastatic disease reported by Hirshberg et al. [14] 12 (5.5 %) were of colorectal origin. Therefore, it is necessary to recommend a full clinical work-up, ruling out metastatic disease, before rendering a diagnosis of CTAT.

As mentioned previously, intestinal-type sinonasal adenocarcinoma (ITAC) has a similar morphologic appearance and potentially could reach the base of tongue via direct extension or metastasis. Metastatic disease from ITAC is rare [15]. Immunophenotypically, these tumors demonstrate CK7, CDX2 and CK20 positivity [16]. As CTAT expresses CK20 and is variably CK7 positive, consideration by the pathologist as to the exact location of the mass and pertinent review of sinonasal imaging is warranted.

Based on the limited cases reported thus far in the literature, the prognosis of this tumor appears to be guarded. Of note, follow-up data available in four of the cases appears to show a favorable outcome in all but one case after multimodality treatment. The only case of mortality arose in the anterior tongue location. Obviously, whether base of tongue location confers a favorable outcome will need to be validated in a large prospective cohort.

In summary, we present a hitherto rare case of primary lingual colonic type adenocarcinoma, an exquisitely rare diagnostic entity with predilection for the base of tongue which may be confused for metastatic disease. We highlight the striking morphologic and immunophenotypic mimicry with colorectal adenocarcinomas and importance of considering CTAT as a differential diagnosis in adenocarcinomas arising from the tongue.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors decline having any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Goldblatt LI, Ellis GL. Salivary gland tumors of the tongue: analysis of 55 new cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 1987;60:74–81. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870701)60:1<74::AID-CNCR2820600113>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pires FR, Pringle GA, de Almeida OP, Chen SY. Intra-oral minor salivary gland tumors: a clinicopathological study of 546 cases. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell D, Kupferman ME, Williams MD, et al. Primary colonic-type adenocarcinoma of the base of the tongue: a previously unreported phenotype. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1798–1802. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slova D, Paniz Mondolfi A, Moisini I, et al. Colonic-type adenocarcinoma of the base of the tongue: a case report of a rare neoplasm. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:250–254. doi: 10.1007/s12105-011-0301-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDaniel AS, Burgin SJ, Bradford CR, et al. Pathology quiz case 2. Diagnosis: primary colonic-type adenocarcinoma of the tongue. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:653–654. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.3240a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llorente JL, Pérez-Escuredo J, Alvarez-Marcos C, et al. Genetic and clinical aspects of wood dust related intestinal-type sinonasal adenocarcinoma: a review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0749-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virchow R. Editorial archive fuer pathologische. Anatomie und Physiologie fuer klinische Medizin. 1855;8:23–54. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratajczak MZ, Schneider G, Sellers ZP, et al. The embryonic rest hypothesis of cancer development—an old XIX century theory revisited. J Cancer Stem Cell Res. 2014;2:e1001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yee KK, Li Y, Redding KY, et al. Lgr5-EGFP marks taste bud stem/progenitor cells in posterior tongue. Stem Cells. 2013;31:992–1000. doi: 10.1002/stem.1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharyya S, Mandal S, Banerjee S, et al. Cannabis smoke can be a major risk factor for early-age laryngeal cancer—a molecular signaling-based approach. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:6029–6036. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pérez-Escuredo J, Martínez JG, Vivanco B, et al. Wood dust-related mutational profile of TP53 in intestinal-type sinonasal adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:1894–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.López F, García Inclán C, Pérez-Escuredo J, et al. KRAS and BRAF mutations in sinonasal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:692–697. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin SJ, Roh JL, Choi SH, et al. Metastatic carcinomas to the oral cavity and oropharynx. Korean J Pathol. 2012;46:266–271. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2012.46.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirshberg A, Shnaiderman-Shapiro A, Kaplan I, et al. Metastatic tumours to the oral cavity-pathogenesis and analysis of 673 cases. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donhuijsen K, Kollecker I, Petersen P, et al. Metastatic behaviour of sinonasal adenocarcinomas of the intestinal type (ITAC) Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:649–654. doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3596-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tilson MP, Gallia GL, Bishop JA. Among sinonasal tumors, CDX-2 immunoexpression is not restricted to intestinal-type adenocarcinomas. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:59–65. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0475-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]