Abstract

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory mucocutaneous disease that often affects the anogenital area and causes significant discomfort and morbidity. Oral mucosal lesions in LS are extremely rare and might be associated with genital and/or skin manifestations. As a unique manifestation of LS, oral lesions are even more rare, with only 20 cases reported in English-language literature. In reviewing that literature in this paper, we present the case of a 44-year-old white man who sought dental assistance with a complaint of a white spot on his upper lip. Extraoral clinical examination revealed a slight white macule on the left upper lip vermilion next to the labial commissure. Intraoral examination revealed that the macule was approximately 3.5 × 2.0 cm, extended to the upper left labial mucosa, and presented an ivory-white color. Following an incisional biopsy and microscopy, the lesion was shown to be covered by a stratified squamous epithelium showing hyperkeratosis and atrophy. The superficial lamina propria revealed a well-marked band of subepithelial hyalinization and, below it, a band-like mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate. Sections stained by Verhoeff’s technique revealed a scantiness of elastic fibers in the superficial lamina propria. The diagnosis of LS was then established. The patient was referred for dermatologic evaluation, which identified no skin or genital lesions, and no treatment was employed. After 6 years, no significant changes in clinical features were observed. Altogether, this rare case makes an important contribution to knowledge on this uncommon condition.

Keywords: Oral mucosa, Histopathology, Mucocutaneous diseases, Lichen sclerosus

Introduction

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory mucocutaneous disease that often appears in the anogenital area and can cause significant discomfort and morbidity [1–4]. Although its etiology remains unknown, several causative factors have been suggested, including autoimmunity, genetic susceptibility, trauma and chronic irritation, hormonal alterations, and infections [4].

LS predominantly affects women and can occur at any age, with peak incidences in prepubescent girls and boys, pre-and postmenopausal women, and middle-aged men [1]. LS lesions can range from small whitish patches to large plaques, which can be associated with atrophy and sclerosis. Genital LS can appear in women in a classic figure-of-eight pattern around the vulva and anus and there cause pruritus, soreness, dysuria, dyspareunia, and pain upon defecation. In men, the glans penis and foreskin are the most affected sites, and patients might complain of pruritus, pain, difficulty in retracting the foreskin, and poor urinary stream. The less common extragenital LS usually appears as generally asymptomatic localized or widespread skin lesions primarily affecting the thighs, breasts, submammary area, neck, back and chest, shoulders, and wrists [2, 4].

In LS, oral mucosal lesions are extremely rare and can be associated with genital and/or skin manifestations. They generally appear as well-demarcated, whitish to ivory-white macules or plaques of variable size and number. As a unique manifestation of LS, oral lesions are even more rare, with only 20 cases of LS exclusively affecting the oral mucosa reported in English-language literature [5–20]. Since knowledge about the condition remains incomplete, in this manuscript we describe a case of LS affecting only the oral mucosa and review related literature.

Case Report

A 44-year-old white man patient sought dental treatment complaining of a white spot on his upper lip. The patient had noticed the lesion 2 months prior and reported mild intermittent discomfort in the area. He had no history of local trauma or surgery, and his other medical history was noncontributory.

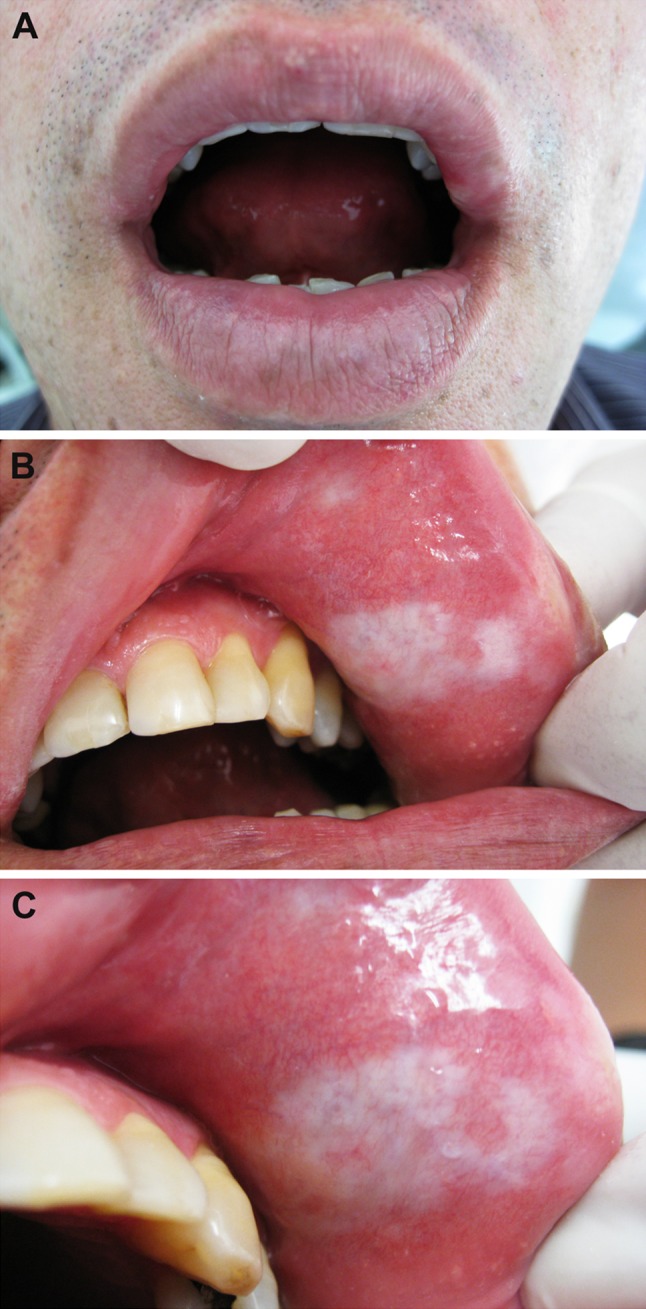

Extraoral clinical examination revealed a slight white macule on the left upper lip vermilion next to the labial commissure (Fig. 1a). Intraoral examination revealed that the macule was approximately 3.5 × 2.0 cm, extended to the upper left labial mucosa, and presented an ivory-white color and hard consistency (Fig. 1b, c). An additional lesion with a similar appearance measuring 0.5 cm in diameter was also observed in the upper labial mucosa (Fig. 1b, c).

Fig. 1.

Clinical aspects of oral lichen sclerosus. a Slight white macule on the left upper lip vermilion. b, c The macule extended to the left labial mucosa, measured approximately 3.5 × 2.0 cm, and showed an ivory-white color. Another similar lesion 0.5 cm in diameter was observed on the upper labial mucosa

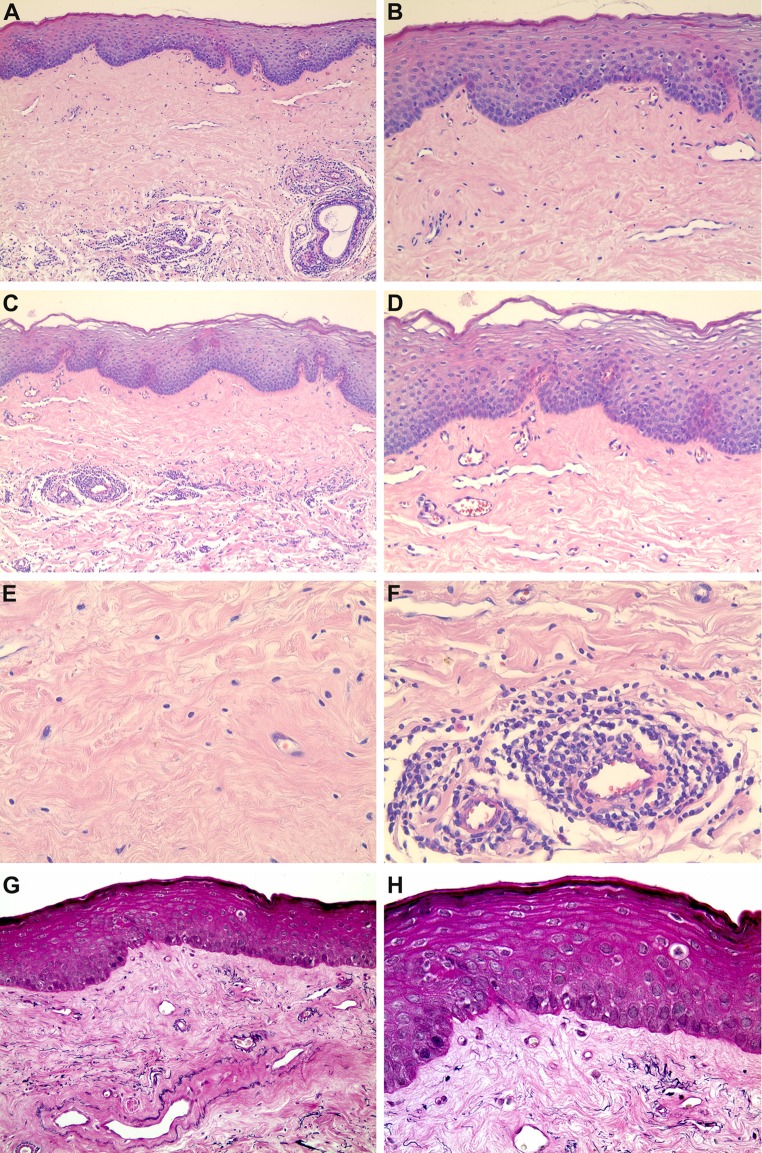

Clinical differential diagnosis included leukoplakia, lichen planus, LS, localized scleroderma, and vitiligo. Once an incisional biopsy was performed and the sample sent to an oral pathology laboratory, light microscopy revealed that the oral mucosa was covered by a stratified squamous epithelium showing areas of hyperkeratosis and atrophy. The superficial lamina propria showed a well-marked band of subepithelial hyalinization composed of thickened and homogenized eosinophilic collagen bundles. Below the hyalinized area, a patchy, band-like mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate sporadically distributed in a perivascular pattern was observed. Scattered telangiectatic blood vessels were also observed in the lamina propria (Fig. 2a–f). Sections stained by Verhoeff’s technique revealed a scantiness of elastic fibers in the superficial lamina propria (Fig. 2g, h). Altogether, the clinical and histological features confirmed the diagnosis of LS.

Fig. 2.

Histological and histochemical features. Oral mucosa sample covered by a stratified squamous epithelium showing areas of hyperkeratosis and atrophy. The superficial lamina propria showed a well-marked band of subepithelial hyalinization, below which appeared a patchy, band-like mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate. Scattered telangiectatic blood vessels were also observed (a HE ×100; b HE ×200; c HE ×100; d HE ×200). The area of subepithelial hyalinization was composed of thickened and homogenized eosinophilic collagen bundles (e HE ×400), and the inflammatory infiltrate was also distributed in a perivascular pattern (f HE ×400). Sections stained by Verhoeff’s technique revealed a scantiness of elastic fibers in the superficial lamina propria (g ×100; h ×200)

The patient was subsequently referred to a dermatologist, who identified no skin or genital lesions. No treatment was employed and in a 6 years follow-up no significant changes in clinical features were observed.

Discussion

LS was first described as a form of clinical presentation of lichen planus [21, 22]. In 1940, Montgomery and Hill [23] first characterized LS as an independent disease and employed for the first time the denomination lichen sclerosus and atrophic. Currently, the term lichen sclerosus is used, since not all cases of LS exhibit atrophy as a histological feature [1].

This mucocutaneous disease has a high predilection to the anogenital area. Extragenital manifestations usually affect the skin and are less common, and oral lesions are extremely rare. In 1957, Miller [24] described the first histologically confirmed case of oral LS, which was in a female patient showing concomitant genital and skin lesions. Since then, few well-documented cases have been reported.

Table 1 summarizes the features of the 20 isolated oral LS reported thus far, as well as of the case presented in this manuscript. The cases demonstrate the condition’s slight predilection in females (12 of 21 cases), whose median age was 25 years, ranging from 7 to 59, whereas it was 44 in men, ranging from 12 to 67. Oral lesions were single in 12 patients and multiple in nine. The most affected sites were the lip vermilion, labial mucosa, buccal mucosa, and tongue, although lesions were also found in the alveolar mucosa, buccal fold, gingiva, and hard and soft palates. Lesions appeared as macules or plaques ranging in color from whitish to ivory-or porcelain-white. Associated atrophic, sclerotic, reddish, telangiectatic, erosive, or ulcerated areas were also reported. Generally well-demarcated, those oral lesions varied in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. Although 14 patients were asymptomatic, six reported symptoms such as discomfort, pain, pruritus, burning, or tightness during mouth opening. In one patient, symptom information was not reported. In the 14 patients for whom the duration of the lesions was clearly reported, the median time was 7.5 months, ranging from 10 days to 56 years. By contrast, LS evolution was unknown in five patients, unspecified in one (i.e., “several months”), and not described for another.

Table 1.

Lichen sclerosus affecting only the oral mucosa previously reported in the English-language literature

| Author | Case | Gender/age | Site(s) | Clinical presentation | Duration | Histopathology | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ravits and Welch [5] | 1 | M/24 | Right upper buccal mucosa and hard palate | Grayish-white atrophic plaque. White atrophic areas. Size: NR. Multiple lesions. Symptoms: NR | 4 months | HYP, HYA, BAN | Vitamin A buccal tablets |

| Macleod and Soames [6] | 2 | F/57 | Tongue and hard palate | White plaques associated with atrophic and erosive areas. Size: NR. Multiple lesions. Painful | Several months | HYP, ATR, HYD, HYA, BAN, PAT | NR |

| Schulten et al. [7] | 3 | F/59 | Right and left upper lip vermilion and tongue | Ivory-white, sharply demarcated, flat lesions. Size: 0.5, 1.5 and 0.2 in diameter. Multiple lesions. Asymptomatic | 3 months | HYP, ATR, HYD, HYA, BAN, DIF | None |

| 4 | M/12 | Left lower lip vermilion | Porcelain-white, sharply demarcated, flat lesion. Size: 0.8 cm in diameter. Single lesion. Asymptomatic | 9 months | Similar to the previous case | Surgical excision | |

| Brown et al. [8] | 5 | M/44 | Mid soft palate | Slightly raised white lesion. Size: 1.0 × 1.5 cm. Single lesion. Asymptomatic | Unknown | HYD, HYA, BAN | None |

| Buajeeb et al. [9] | 6 | F/22 | Right buccal mucosa and mucobuccal fold extending to the labial mucosa and lower lip vermilion | White macular lesion. Size: 7.0 × 2.0 cm. Single lesion. Pain during tooth brushing. Tightness on opening the mouth | NR | HYP, ATR, HYD, HYA, DIF, TEL, SEF | Topical and intralesional corticosteroids |

| Jimenez et al. [10] | 7 | F/19 | Upper lip frenulum, buccal fold and vestibular gingiva | Well-defined whitish. Size: 1.0 cm in diameter. Single lesion. Mild discomfort | Unknown | ATR, HYA, PER | Intralesional corticosteroid |

| Rajlawat et al. [11] | 8 | F/14 | Right lower lip vermilion extending to the labial and buccal mucosa | Macular, ivory-white lesion. Size: 3.0 × 1.5 cm. Single lesion. Asymptomatic | 1 year | ATR, CLE, HYA, DIF, SEF | Topical corticosteroid |

| Mendonça et al. [12] | 9 | F/20 | Right lower lip vermilion extending to the labial mucosa | White macule. Size: 7.0 × 2.0 cm. Single lesion. Asymptomatic | Unknown | ATR, HYD, HYA, DIF, SEF, S-100 | None |

| Kelly et al. [13] | 10 | F/10 | Right lower lip vermilion extending to the labial mucosa | Well-demarcated, atrophic white plaque with a central fissure. Size: 1.5 × 1.2 cm. Single lesion. Asymptomatic | 2 years | HYA, PAT | Topical corticosteroid |

| Azevedo et al. [14] | 11 | M/19 | Buccal and lower labial mucosa | Irregular whitish plaque. Size: NR. Multiple lesions. Asymptomatic | 8 months | ATR, HYD, HYA, BAN, SEF, S-100 | None |

| 12 | F/34 | Upper lip vermilion extending to the labial mucosa and buccal sulcus | Irregular whitish plaque and ulcer. Size: NR. Multiple lesions. Pruritus, burning and tightness on opening the mouth | 3 months | Similar to the previous case | Surgical excision | |

| 13 | F/28 | Tongue, buccal and lower labial mucosa | Irregular whitish plaque. Size: NR. Multiple lesions. Pruritus, burning and tightness on opening the mouth | 7 months | Similar to the previous case | None | |

| Sherlin et al. [15] | 14 | M/60 | Bilateral on the buccal mucosa. Vestibular gingiva and alveolar mucosa | White patches with reddish areas. Size: 2.0 × 2.0 cm and 3.0 × 2.0 cm. Multiple lesions. Asymptomatic | 6 months | ATR, HYD, HYA, PAT, SEF | None |

| Kim et al. [16] | 15 | F/7 | Left lower lip vermilion and labial mucosa extending to the anterior buccal fold and alveolar mucosa | Well-demarcated, creamy-white, atrophic plaque with sclerosis and telangiectasia. Size: 2.5 × 1.5 cm. Single lesion. Asymptomatic | 2 years | HYD, HYA, PAT | Topical corticosteroid and pimecrolimus |

| Liu et al. [17] | 16 | F/54 | Tongue | Well-demarcated, atrophic, porcelain white plaque. Size: approximately 2.0–3.0 cm2. Single lesion. Asymptomatic | 10 days | ATR, HYD, HYA, DIF, TEL | Topical tacrolimus |

| 17 | F/58 | Tongue | White plaque. Size: approximately 2.5–3.0 cm2. Single lesion. Asymptomatic | 2 years | ATR, HYA, DIF | Topical tacrolimus | |

| George et al. [18] | 18 | M/20 | Upper labial mucosa and maxillary gingiva | White lesions. Size: 1 cm. Multiple lesions. Asymptomatic | Unknown | ATR, HYD, HYA, BAN, BOR | NR |

| De Aquino et al. [19] | 19 | M/47 | Upper lip frenulum extending to the alveolar mucosa | Well-limited white patche with red areas. Size: 2.0 × 1.5 cm. Single lesion. Asymptomatic | Unknown | ATR, HYD, CLE, HYA, BAN, PER, SEF | Surgical excision |

| Tupsakhare et al. [20] | 20 | M/67 | Right soft palate | Well-demarcated whitish-gray plaque. Size: 0.8 × 0.8 cm. Single lesion. Asymptomatic |

56 years | HYP, ATR, HYD, CLE, HYA, DIF, SEF | Surgical excision |

| Marangon-Júnior et al. (current case) | 21 | M/44 | Left upper lower lip vermilion extending to the labial mucosa | Well defined, ivory-white macules. Size: 3.5 × 2.0 cm and 0.5 cm in diameter. Multiple lesions. Mild, intermittent discomfort | 2 months | HYP, ATR, HYA, BAN, PAT, PER, TEL, SEF | None |

The current case was also included

M, male; F, female; NR, not reported; HYP, oral epithelium showing hyperkeratosis; ATR, oral epithelium showing atrophy; HYD, oral epithelium showing hydropic degeneration of basal cells; CLE, focal subepithelial clefting; HYA, hyalinization of superficial lamina propria; BAN, underlying band-like mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate; PAT, underlying patchy mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate; DIF, underlying diffuse mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate; PER, underlying inflammatory infiltrate consisting mainly of perivascular lymphocytes; TEL, telangiectatic blood vessels in the lamina propria; SEF, scantiness of elastic fibers in the superficial lamina propria shown by Verhoeff’s stain; S-100, immunoreactivity for S-100 protein in some clear basal cells; BOR, presence of spirochaete immunopositive for Borrelia (focus-floating microscopy)

The main clinical differential diagnosis of oral LS involves localized scleroderma (morphea), systemic scleroderma, lichen planus, leukoplakia, vitiligo, and oral submucous fibrosis [12, 14, 25]. Although it may be difficult to clinically distinguish oral LS from other oral mucosal white lesions, some issues important to the clinical differential diagnosis should be considered: localized scleroderma should be quite similar to LS and it is the most relevant lesion to be considered in the differential diagnosis [14, 15, 26]; patients with systemic scleroderma may show thickening of the skin, involvement of other organs, and Raynaud’s phenomenon [26]; oral lichen planus lesions frequently present as white reticular striations and only a limited number of patients show dense white homogeneous plaques [9, 15]; oral leukoplakia shows a high diversity of clinical appearances, varying from small macules to thick plaques, and it is mostly seen in smokers [9, 15]; most patients with oral manifestations of vitiligo show areas of skin depigmentation [27]; patients with oral submucous fibrosis commonly show a history of areca nut use and progressive fibrosis of the oral soft tissues [9, 28].

The histological features of LS are typical and usually appropriate to exclude the aforementioned conditions, although the differences should be subtle [12, 14]. The reported cases of oral LS (Table 1) exhibit six main histological features: (1) hyperkeratosis, atrophy or focal degeneration of basal cells of the oral mucosa epithelium; (2) subepithelial clefting; (3) hyalinization of superficial lamina propria; (4) underlying diffuse, patchy, or band-like mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate; (5) perivascular inflammation; and (6) telangiectatic blood vessels. The most marked of those features are the hyalinization of the superficial lamina propria and the underlying mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate. Histochemical techniques such as Verhoeff’s stain have been used to confirm the oral LS diagnosis by the scantiness of elastic fibers in the superficial lamina propria (Table 1). The main histological differences between LS and its principal differential diagnosis are the following: scleroderma involves the deep lamina propria, present no loss of elastic fibers and exhibit no band-like mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate [8–10, 12, 14, 17]; lichen planus do not display hyalinization of superficial lamina propria and exhibit a band-like inflammatory mononuclear infiltrate just below the oral mucosal epithelium [9, 12, 17]; leukoplakia may present different degrees of epithelial dysplasia and no hyalinization of superficial lamina propria, as well as no band-like mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate [9]; immunoreaction for the S-100 protein in basal cells of the oral epithelium excludes vitiligo, that also lacks the hyalinization of superficial lamina propria [8, 12, 14, 17]; oral submucous fibrosis may show pyknotic changes in the nuclei of the basal cell layer and epithelial dysplasia, as well as blood vessel obliteration or narrowing [9, 12, 17].

Although LS has no curative treatment, the management of anogenital lesions is relevant since it can cause significant discomfort and morbidity, including anatomical alterations, fibrosis, and stenosis. Less commonly, genital lesions can be complicated by the development of squamous cell carcinoma. Such management often involves controlling symptoms (e.g., by topical corticosteroids), the prevention or treatment of complications, and long-term surveillance [2–4]. The treatment of oral lesions is usually unnecessary, because most patients are asymptomatic or report minor symptoms [5–20]. In some cases, it should be employed to reduce symptoms or in response to aesthetic complaint [14]. In the 20 isolated oral LS cases reported, as well as in the present one, the following treatment protocols were used (Table 1): no treatment (7 patients); surgical excision (4 patients); topical corticosteroids (2 patients); topical tacrolimus (2 patients); intralesional corticosteroids (1 patient); topical and intralesional corticosteroids (1 patient); topical corticosteroid and pimecrolimus (1 patient); and vitamin A tablets (1 patient). In two patients, data regarding treatment were not reported.

In conclusion, oral LS is an exceptionally rare lesion that should nevertheless be considered in the presence of whitish to ivory-white macules or plaques. The hyalinization of the superficial lamina propria and underlying mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate are characteristic microscopic features that usually recommend the diagnosis of LS. Oral lesions usually do not demand treatment, except in the presence of significant symptoms or aesthetic complaint. The occurrence of skin or genital lesions needs to be evaluated, since it may cause significant discomfort and morbidity. The case described in this manuscript therefore contributes to expanding knowledge regarding this uncommon condition.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG). Dr. RS Gomez is research fellow of CNPq, and H. Marangon-Júnior has received a CAPES Fellowship.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(3):393–416. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353(9166):1777–1783. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tasker GL, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28(2):128–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14(1):27–47. doi: 10.1007/s40257-012-0006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravits HG, Welsh AL. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus of the mouth. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;76:56–58. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1957.01550190060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macleod RI, Soames JV. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus of the oral mucosa. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:64–65. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90180-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulten EA, Starink TM, van der Waal I. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus involving the oral mucosa: report of two cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993;22:374–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1993.tb01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown AR, Dunlap CL, Bussard DA, Lask JT. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus of the oral cavity. Report of two cases. Oral surg oral med, oral pathol. 1997;84:165–170. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(97)90064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buajeeb W, Kraivaphan P, Punyasingh J, Laohapand P. Oral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1999;88:702–706. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(99)70013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiménez Y, Bagán JV, Milián MA, Gavaldá C, Scully C. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus manifesting with localized loss of periodontal attachment. Oral Dis. 2002;8:310–313. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.02858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajlawat BP, Triantafyllou A, Field EA, Parslew R. Lichen sclerosus of the lip and buccal mucosa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:684–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendonça EF, Ribeiro-Rotta RF, Silva MAGS, Batista AC. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:637–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly SC, Helm KF, Zaenglein AL. Lichen sclerosus of the lip. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:500–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azevedo RS, Romañach MJ, de Almeida OP, Mosqueda-Taylor A, Vega-Memije ME, Carlos-Bregni R, Contreras-Vidaurre E, López-Jornet P, Saura-Inglés A, Jorge J. Lichen sclerosus of the oral mucosa: clinicopathological features of six cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38:855–860. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.03.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherlin HJ, Ramalingam K, Natesan A, Ramani P, Premkumar P, Thiruvenkadam C. Lichen sclerosus of the oral cavity. Case report and review of literature. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;3:38–43. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2010.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim CY, Kim JG, Oh CW. Treatment of oral lichen sclerosus with 1% pimecrolimus cream. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:326–329. doi: 10.5021/ad.2010.22.3.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Hua H, Gao Y. Oral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus—literature review and two clinical cases. Chin J Dent Res. 2013;16:157–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.George AA, Hixson CD, Peckham SJ, Tyler D, Zelger B. A case of oral lichen sclerosus with gingival involvement and Borrelia identification. Histopathology. 2014;65:146–148. doi: 10.1111/his.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Aquino Xavier FC, Prates AA, Gurgel CA, De Souza TG, Andrade RG, Goncalves Ramos EA, Pedreira Ramalho LM, Dos Santos JN. Oral lichen sclerosus expressing extracellular matrix proteins and IgG4-positive plasma cells. Dermatol Online J. 2014. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/3q39n03w [PubMed]

- 20.Tupsakhare S, Patil K, Patil A, Sonune S. Lichen sclerosus of soft palate: a rare case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2016;59:216–219. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.182044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du Hallopeau H. lichen plan et particulierement de sa forme atrophique: lichen plan sclereux. Ann Dermatol Syph. 1887;8:790–791. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darier J. Lichen plan sclereux. Ann Dermatol Syph. 1892;23:833–837. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery H, Hill WR. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1940;42:755–779. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1940.01490170003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller RF. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with oral involvement; histopathologic study and dermabrasive treatment. AMA Arch Derm. 1957;76(1):43–55. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1957.01550190047010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Araújo VC, Orsini SC, Marcucci G, de Araújo NS. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;60(6):655–657. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung L, Lin J, Furst DE, Fiorentino D. Systemic and localized scleroderma. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24(5):374–392. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagarajan A, Masthan MK, Sankar LS, Narayanasamy AB, Elumalai R. Oral manifestations of vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60(1):103. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.147844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arakeri G, Brennan PA. Oral submucous fibrosis: an overview of the aetiology, pathogenesis, classification, and principles of management. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51(7):587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]