Abstract

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is a tumor of mesodermal origin that arises from the serosa of the pleura, peritoneum, pericardium or tunica vaginalis. MPM is well known to have a poor prognosis with a median survival time of 12 months. Accurate diagnosis, staging and restaging of MPM are crucial with [18F] flurodeoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET/CT) playing an increasingly important role. Here we report a case of MPM with unusual contiguous soft tissue spread of the tumor along the dermal and fascial planes characterized by PET/CT. Given that the loco-regional tumor in the thorax was under control on PET/CT, the death of the patient was most likely associated with physiologic or metabolic causes associated with an extra-thoracic tumor.

Keywords: Malignant mesothelioma, Metastases, FDG PET/CT, Adjuvant chemotherapy

Introduction

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is a tumor of mesodermal origin that arises from the serosa of the pleura, peritoneum, pericardium or tunica vaginalis. Most cases of mesothelioma are associated with remote asbestos exposure. The primary treatments of MPM include surgical resection, chemotherapy and radiation [1]. The prognosis of MPM is poor with most of the patients having unresectable disease at the time of diagnosis and a median survival time of 12 months. Random studies have shown that combination chemotherapy including cisplatin and premetrexed is associated with increased survival [2]. Based on an ongoing clinical trial, with trimodality therapy the survival time can be extended to 20–29 months. Therefore, early diagnosis and accurate staging are crucial in case of MPM. Preferably video-assisted thoracotomy (VAT)-guided pleural biopsy should be performed in order to obtain adequate tissue. CT chest is considered the initial imaging modality for malignant mesothelioma with the limitation of evaluating local invasion and differentiating benign or malignant soft tissue abnormalities. FDG PET/CT has been increasingly used for the characterization, staging and restaging of MPM recently (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

Fig. 1.

a Post-surgery and chemo-radiation restaging PET MIP image demonstrates active tumor in the right lung apical pleura extending into the chest wall. Probably active metastases of the mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes (not shown). Mild FDG uptake in the right lower thorax and flank favors representing post-surgical changes without evidence of local recurrence. b Post-chemoradiation restaging PET MIP image demonstrates an interval decrease of FDG avidity of the right apical pleural tumor and thoracic lymphadenopathy. No evidence of recurrence in the right lower thorax. c Post-palliative chemotherapy restaging PET MIP image demonstrates extensive and intense hypermetabolic metastatic mesothelioma in the skin, subcutaneous tissue and musculature involving the right neck and bilateral chest, abdomen, pelvis and thighs, right greater than left. The most active disease is in the bilateral scrotum and perineum with concern for possible involvement of the testicles and rectum. Right pleural tumor and mediastinal lymph nodes are stable

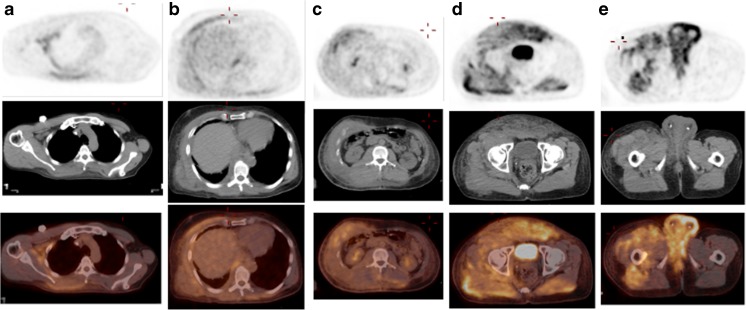

Fig. 2.

a, b, c, d Post-palliative chemotherapy restaging PET (from the same PET exam on Fig 1. c) axial attenuation corrected PET, non-contrast CT and fusion images at the levels of axilla, lower thorax, mid abdomen, pelvis and perineum show no pleural or peritoneal metastasis and tumor spread in the skin, subcutaneous tissue, musculatures and possible testicle and rectum involvement

Fig. 3.

a, b, c Contrast CT images at the level of the lower chest, mid abdomen and pelvis show asymmetric diffuse soft tissue stranding and thickening consistent with tumor spread in the skin, subcutaneous soft tissue and musculature

Case Report

A 55-year-old male was diagnosed with epithelioid-type malignant mesothelioma of the right hemithorax. The patient was treated with neoadjuvant cisplatin/ALIMTA and surgery initially (right radical pleurectomy with resection and reconstruction of the diaphragm) followed by adjuvant Paclitaxel and radiation therapy. The post-surgical pathology staging was pT3N0M0. The first restaging PET/CT showed a single pleural tumor in the right apex and likely multiple metastatic lymph nodes of the mediastinum and hilum without evidence of local recurrence. Metastatic disease of the right inguinal area was found 6 months later, and the patient was treated by palliative Gemzar. Six months after the completion of palliative chemotherapy, the patient presented with progressive swelling in the suprapubic area, scrotum and right leg. FDG-PET/CT demonstrated markedly increased disease extending from the right neck, bilateral torso, bilateral thighs, bilateral scrotum and perineum, whereas the intrathoracic uptake was either decreased or stable. With the guide of PET/CT images, cutaneous biopsy confirmed recurrent malignant mesothelioma. The patient died 3 months later because of significant progression of the metastatic disease.

Discussion

Metastases of MPM usually occur by local invasion. Hematogenous distant metastasis is rare, but there are case reports of distant metastases to the liver, spleen, adrenal, bone, brain, thyroid, tongue, skin, muscle, etc. [3–6]. Postmortem studies show the distant metastatic disease of MPM is likely underestimated [7]. Here we report an unusual case of distant metastases of MPM in the soft tissue after aggressive surgical resection, chemotherapy and radiation. Only a small number of cases of subcutaneous metastases of MPM have been reported with the majority of the metastases to the face or scalp [4]. The current case is unusual and different from other reported cases on the pattern of contiguous spread of MPM along the dermal, muscular and fascial planes. Based on the serial PET examinations, we believe this pattern of spread can be attributed to local invasion, which is characteristic for MPM. For the current case, PET/CT demonstrates key roles in (1) the pre-surgical characterization and staging; (2) evaluation of the response to treatment; (3) accurate detection of distant metastases; (4) estimating the extent of metastatic disease; (4) selecting the site for tissue biopsy.

PET/CT findings in malignant mesothelioma are commonly of unilateral circumferential pleural uptake. FDG PET has been shown to have sensitivity of 95–97 % and specificity of 78–92 % for the evaluation of primary MPM [8–13]. PET/CT is superior to other imaging modalities for evaluation of distant metastatic disease of MPM given its whole-body capability. In patients planned for surgical resection, PET/CT is accurate for distinct M0 and M1 tumors or T3 and T4 tumors. The literature has shown that the use of FDG-PET in addition to CT may up- or downstage patients leading to changes in the management in 20–38 % of patents [1]. Another emerging role of PET/CT on MPM is to assess the response to chemotherapy and radiation before measurable morphology changes on CT. Carretta et al. [9] reported that reduction of FDG uptake in comparison with pretreatment values suggested response to chemotherapy when contrast CT showed stable disease. An interesting observation concerning the current case is that the loco-regional disease was under control because of aggressive therapy. However, the patient developed diffuse extrathoracic metastases and died afterward. The exact cause of death in MPM is poorly understood. A postmortem study of 318 MPM cases by Finn et al. found no anatomic cause of death in the majority of the patients [7], raising the possibility of physiologic or metabolic causes of death.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

No funding support of the project.

Conflict of Interest

Yuyang Zhang, Jamie Edwards, Zhonglin Hao, Samir Khleif, Hadyn Williams and Darko Pucar declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

No institutional review board or the equivalent was required for the manuscript. There was no requirement of informed consent for the case report.

Footnotes

This article has not been published before and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. It has been approved by all co-authors.

References

- 1.van Zandwijk N, Clarke C, Henderson D, Musk AW, Fong K, Nowak A, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5:E254–E307. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.11.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Meerbeeck JP, Gaafar R, Manegold C, Van Klaveren RJ, Van Marck EA, Vincent M, et al. Randomized phase III study of cisplatin with or without raltitrexed in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: an intergroup study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Lung Cancer Group and the National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6881–6889. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20005.14.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chari A, Kolias AG, Allinson K, Santarius T. Cerebral metastasis of a malignant pleural mesothelioma: a case report and review of the literature. Cureus. 2015;7:e241. doi: 10.7759/cureus.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elbahaie AM, Kamel DE, Lawrence J, Davidson NG. Late cutaneous metastases to the face from malignant pleural mesothelioma: a case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:84. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vazquez MV, Selvendran S, Cheluvappa R, McKay MJ. Peritoneal mesothelioma metastasis to the tongue—comparison with 8 pleural mesothelioma reports with tongue metastases. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2016;5:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2015.12.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamagishi T, Fujimoto N, Miyamoto Y, Asano M, Fuchimoto Y, Wada S, et al. Brain metastases in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2016;33:231–237. doi: 10.1007/s10585-015-9772-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finn RS, Brims FJ, Gandhi A, Olsen N, Musk AW, Maskell NA, et al. Postmortem findings of malignant pleural mesothelioma: a two-center study of 318 patients. Chest. 2012;142:1267–1273. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benard F, Sterman D, Smith RJ, Kaiser LR, Albelda SM, Alavi A. Metabolic imaging of malignant pleural mesothelioma with fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Chest. 1998;114:713–722. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.3.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carretta A, Landoni C, Melloni G, Ceresoli GL, Compierchio A, Fazio F, et al. 18-FDG positron emission tomography in the evaluation of malignant pleural diseases—a pilot study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;17:377–383. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(00)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerbaudo VH, Sugarbaker DJ, Britz-Cunningham S, Di Carli MF, Mauceri C, Treves ST. Assessment of malignant pleural mesothelioma with (18)F-FDG dual-head gamma-camera coincidence imaging: comparison with histopathology. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:1144–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bury T, Paulus P, Dowlati A, Corhay JL, Rigo P, Radermecker MF. Evaluation of pleural diseases with FDG-PET imaging: preliminary report. Thorax. 1997;52:187–189. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duysinx B, Nguyen D, Louis R, Cataldo D, Belhocine T, Bartsch P, et al. Evaluation of pleural disease with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging. Chest. 2004;125:489–493. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer H, Pieterman RM, Slebos DJ, Timens W, Vaalburg W, Koeter GH, et al. PET for the evaluation of pleural thickening observed on CT. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]