Abstract

The enzyme β-galactosidases have been isolated from various sources such as bacteria, fungi, yeast, vegetables, and recombinant sources. This enzyme holds importance due to its wide applications in food industries to manufacture lactose-hydrolyzed products for lactose-intolerant people and the formation of glycosylated products. Absorption of undigested lactose in small intestine requires the activity of this enzyme; hence, the deficiency of this enzyme leads to lactose intolerance. Lactose intolerance affects around 70% of world’s adult population, while the prevalence rate of lactose intolerance is 60% in Pakistan. β-Galactosidases are not only used to manufacture lactose-free products but also employed to treat whey, and used in prebiotics. This review focuses on various sources of β-galactosidase and highlights the importance of β-galactosidases in food industries.

Keywords: β-Galactosidase, Lactose hydrolysis, Galactooligosaccharide, Whey

Introduction

β-Galactosidase, commonly known as lactase, is an enzyme responsible to hydrolyze lactose. This enzyme has wide applications in food-processing industries. The presence of excessive lactose in intestine typically leads to tissue dehydration and reduced calcium absorption due to low acidity that causes diarrhea, flatulence, and cramps (Carrara and Rubiolo 1994; Felicilda-Reynaldo and Kenneally 2016; Vandenplas 2015; Lukito et al. 2015). Absorption of lactose requires the activity of lactase enzyme, found in small intestine that functions by splitting the bond linking the two sugars (monosaccahrides). The deficiency of this enzyme in intestine leads to lactose intolerance, and the people suffering from it are unable to consume milk and dairy products. Furthermore, the ability of this enzyme to produce a colored product during a chemical reaction has gained its importance in molecular biology (Ianiro et al. 2017; Shukla and Wierzbicki 1975).

β-Galactosidase is basically a tetramer of four identical polypeptide chains with each chain consisting of 1023 amino acids which combine to form five well-defined structural domains. One of these domains is a jelly roll barrel, while the remaining domains consist of fibronectin, β-sandwich, and a central domain with TIM-type barrel that also serves as the active site (Huber et al. 1976).

The central domain is catalytically active and is made of the tetramer subunits. Dissociation of tetramer into dimers inactivates the active site. The sequence at the amino terminal of this enzyme consists of α-peptide which is involved in α-complementation and plays a role in subunit interface (Corral et al. 2005).

As an enzyme, β-galactosidase cleaves the disaccharide lactose to produce galactose and glucose which then ultimately enter glycolysis. This enzyme also causes transgalactosylation reaction of lactose to allolactose which then finally cleaved to monosaccharides. Upon binding to lacZ repressor, this allolactose regulates the amount of β-galactosidase in the cell by creating positive feedback (Pivarnik and Senecal 1995).

People who are intolerant to this sugar have deficiency of β-galactosidase in their small intestine. This enzyme is present in mammals during the breast-feeding period; however, in most of the individuals, β-galactosidase activity decreases after this period, which characterizes primary hypolactasia and creates symptoms of lactose intolerance. This disorder affects about 70% of the world’s adult population. The prevalence of lactose intolerance in Western countries varies from 4 to 50%, while its prevalence in Pakistan is about 60% (Priebe et al. 2002).

Industrially, β-galactosidase has various applications. Besides producing lactose-free products for lactose-intolerant individuals, β-galactosidases are also used to solve whey disposal issues on commercial scale (Karasova et al. 2002). Lactose is hygroscopic and causes crystallization in food products; hence, β-galactosidases are used to hydrolyze lactose to solve lactose-related crystallization in frozen, concentrated desserts. This treatment usually decreases lactose content of milk to be used by intolerant individuals (Champluvier et al. 1988).

Furthermore, dairy whey, a byproduct of cheese industry is usually treated with this enzyme. Whey disposal has become a serious environmental issue since it is disposed into water streams, thereby causing severe water pollution (Brandão et al. 1987). β-Galactosidase are used to treat whey to convert it into useful products such as ethanol and sweet syrup that has further wide range of applications in confectionary, bakery, and other industries (Zhou and Chen 2001).

The sources of β-galactosidases are microbial, vegetable, and animal origin. However, usually microbial sources show higher productivity, and consequently, using them results in reduction of costs. The choice of sources basically depends on the required reaction conditions; for instance, bacterial β-galactosidases work with optimal pH between 2.5 and 5.4 and are mainly used for acidic whey hydrolysis. In contrast, yeast β-galactosidase shows maximum activity at pH 6.0–7.0 which is more suitable for the hydrolysis of milk and sweet whey.

Sources of β-galactosidases

β-Galactosidase is found in bacteria, fungi, and yeasts. In plants, it is mainly found in almonds, peaches, apples, and apricots. However, on a commercial and an industrial scale, the most commonly used sources of β-galactosidase are Aspergillus and Kluyveromyces (Zhou and Chen 2001).

Bacterial sources

β-Galactosidase extracted from bacterial sources has been used for lactose hydrolysis due to several advantages including their high activity, ease of fermentation, and the stability of the enzyme. β-Galactosidase obtained from Bifidobacterium (a probiotic organism) is utilized in food and food systems. β-Galactosidase from various bacterial strains like Bifidobacterium infantis strain CCRC 14633, Bifidobacterium longum strain CCRC 15708 and Bifidobacterium longum CCRC15708 has shown highest enzyme activity (Hsu et al. 2005). Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species are effective probiotics, and hence. they are widely used as potential sources of β-galactosidase. Lactobacilli isolated from piglet’s gastrointestinal tract (GIT) are also used in the production of various fermented milk products. Moreover, β-galactosidase derived from the porcine strains of Lactobacilli has the ability to ferment lactose in milk from bovine sources. In humans, this enzyme is abundantly found in colon where it facilitates lactose fermentation, and its activity is measured to indicate the capacity of microbiota of the colon to ferment the intestinal lactose (Jain et al. 2007).

Yeast sources

Yeast Kluyveromyceslactis is one of the commercially important sources of β-galactosidase which is ubiquitously found in dairy environment. Isolating β-galactosidase from yeast is of interest due to its use in the production of lactose-free dairy and milk products (Pivarnik and Senecal 1995). The optimal pH of yeast β-galactosidase lies between 6.0 and 7.0. Kluyveromyces marxianus is reported to produce β-galactosidase’s homologous enzymes and other heterologous proteins that were found to grow on a range of substrates with lactose as their only energy source. Moreover, cold-active acidic β-galactosidase isolated from a strain of psychrophilic yeast species called Guehomyce spullulans has been used in food industries for whey and milk hydrolysis. The activities of different β-galactosidase are influenced by the presence of various ions. Yeast β-galactosidase Kluyveromyces lactis and Kluyveromyces fragilis require ions such as Manganese (Mn2+), Sodium (Na+), and Magnesium (Mg2+), while the presence of heavy metals and Calcium (Ca2+) inhibits the enzyme activity. The properties of bacterial and yeast β-galactosidase are tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Properties of bacterial and yeast β-galactosidases

| Microorganisms | Location of enzyme (intracellular/extracellular) | Temperature (°C) | pH | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||||

| Escherichia coli | Intracellular | 40 | 7.2 | |

| Lactobacillus thermophilus | Intracellular | 55 | 6.2 | |

| Bacillus circulans | Intracellular | 56 | 6.5 | Boon and Janssen (2000) |

| Leuconostoc citrovorum | Intracellular | 65 | 6.0 | Rao and Dutta (1978) |

| Yeast | ||||

| Kluyveromyces lactis | Intracellular | 30–35 | 6.5–7.0 | Roy and Gupta (2003) |

| Kluyveromyces fragilis | Intracellular | 30–35 | 6 | Roy and Gupta (2003) |

Fungal sources

Fungal β-galactosidases possess optimal acidic pH range of 2.5–5.4, thus making them more effective for the hydrolysis of lactose found in acidic substances like whey. Fungi produce highly stable enzymes. The most common fungal sources of β-galactosidases are Kluyveromyces lactis, Kluyveromyces fragilis (Sacchoramyces fragilis), and some Aspergillus species which are accepted as “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) by FDA. Aspergillus oryzae produces extracellular β-galactosidase that is used on commercial scale. β-Galactosidase from Aspergillus oryzae was purified and characterized by Park and co-workers with optimal pH and temperature of 5 and 50 °C with galactose as a competitive inhibitor and glucose a noncompetitive inhibitor, respectively. Aspergillus oryzae originated enzyme was reported to be more applicable for whey utilization as compared to lactose hydrolysis. Aspergillus niger originated β-galactosidase are usually involved in the removal of the galactose residues from oligosaccharides and polysaccharides derived from plants, rather than in lactose hydrolysis (Kazemi et al. 2016). This has been proven through different expression rates on carbon sources, where the highest expression of this enzyme-encoding lacA gene has been reported on arabinose, pectin, and xylose (Borglum and Sternberg 1972). Several studies showed the purification of fungal β-galactosidases via techniques like chromatography on DEAE-cellulose, ammonium sulfate fractionation, DEAE-Sephadex column choromatography, etc. The properties of fungal β-galactosidases are tabulated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Properties of fungal β-galactosidases

| Sr.# | Fungal source of β-galactosidases | Optimal temperature (°C) | Optimal pH | Location of the enzyme (Extracellular/intracellular) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aspergillus niger | 55 | 3.5–4.5 | Unknown | Haider and Husain (2007a, b) |

| 2 | Kluyveromyces fragilis | 35–45 | 6.3–6.5 | Cell bound | |

| 3 | Aspergillus foetidus | 66–67 | 3.5–4 | Extracellular | Roy and Gupta (2003) |

| 4 | Aspergillus oryzae | 55–60 | 4.5–5 | Extracellular | |

| 5 | Neurospora crassa | 4 | – | Extracellular |

Plants

β-Galactosidases are also widely distributed in plants where they play roles by contributing to plant growth, lactose hydrolysis, and fruit ripening. This enzyme is reported to involve in ripening of persimmons by decreasing the galactosyl content of cell wall, which facilitates the fruit-ripening process. Galactosidases from papaya source cause cell wall hydrolysis and consequently softening of the fruit during the ripening process. Moreover, β-galactosidase activity has also been reported in cell wall of strawberry (Fragaria ananassa) where the fruit softens due to the release of free sugars during the ripening process. Moreover, Smith and Gross (2000) identified a family of seven β-galactosidases from tomato during the fruit-ripening process. Furthermore, softening-related β-galactosidases have been purified from the fruits of tomato, apple, muskmelon, avocado, kiwifruit, coffee, mango, and Japanese pear plants (Seddigh and Darabi 2014).

Applications of β-galactosidase in Food Industry

Production of hydrolyzed milk products

Lactose as a disaccharide sugar is found in milk and hence also in the products that are manufactured from milk. The function of lactose is to stimulate the growth of the beneficial bacteria residing in small intestine, i.e., ‘bifidobacteria’ (Silanikove et al. 2015). The absorption of lactose requires the activity of lactase enzyme since excessive undigested lactose leads to flatulence, diarrhea, and cramps. A significant percentage of the world’s adult population develops deficiency of lactase enzyme that leads to disorder known as lactose intolerance (Sitanggang et al. 2016; Mahoney 2003).

There exist basically three types of lactase deficiency, namely, primary, congenital, and secondary. Primary lactase deficiency occurs in people aged between 2 to 20 years. Primary lactase deficiency is a more common type, which occurs due to the reduced synthesis of β-galactosidase along the brush borders of small intestine (lactase). Congenital lactase deficiency, the second type of actase deficiency, occurs due to genetic abnormality which is characterized by either a very small amount of this enzyme in patients or by this enzyme being totally absent in the affected individuals. The third type, known as secondary lactase deficiency, occurs as a result of low levels of this enzyme due to an underlying disease affecting GI tract (El-Gindy 2003). The prevalence of lactose intolerance in Asian populations is about 90%. People afflicted with lactose intolerance consume dairy-fermented products that contain either no or very little amount of lactose (Xao et al. 2008).

Treating milk products with β-galactosidase offers a solution to this problem through pre-hydrolyzation of milk and milk-related products that reduce lactose concentration (Rao and Dutta 1978). On a commercial scale, bacterial and fungal lactase enzymes are being used to treat milk products. Medicines containing β-galactosidase are also available, which are taken before consuming milk products (Francesconi et al. 2016). These medicines possess fungal-derived β-galactosidases, usually Aspergillus, that is stable at low pH allowing for the proper functioning in stomach (Panesar et al. 2007).

In food industries, lactose hydrolysis is not only preferred to produce lactose-free products but also used to reduce the crystallization in ice creams and condensed milk, which occurs due to high lactose concentration. Use of β-galactosidase in treating lactose not only improves the texture but also makes the products more easily digestible. The end-products of lactose hydrolysis (i.e., glucose and galactose) ferment more easily, thus reducing the overall time required to achieve the preferred pH in various food items such as yogurts and cottage cheese. Furthermore, it also reduces the need to add additional sweeteners, thus lowering the amount of calories in the final product (Domingues et al. 2005).

Microbial β-galactosidases are known to be used not only in the production of lactose-hydrolyzed milk; however, several studies suggest that they are also used in the production of other industrially important products such as ethanol and biosensors. For instance, Rodríguez et al. (2006) reported the production of ethanol and extracellular β-galactosidase enzyme from a recombinant S. cerevisiae (Rodríguez et al. 2006). Ethanol productivity of 9 g/I hour was reported along with the production of lactase enzyme. Moreover, Grosová et al. (2009) also confirmed this observation. The latter study was conducted to determine the kinetic analysis of alcoholic fermentation using S. cerevisiae, and an increase in the ethanol production was observed (Grosová et al. 2009). Hence, these experiments showed that the initial increase in lactose concentration improved the ethanol production linearly.

Whey utilization

Cheese industry produces large quantities of whey as a byproduct, which when disposed into water streams, causes water pollution, since lactose is related to biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and chemical oxygen demand (COD). The main components of whey are lactose, minerals, and proteins. Even though a significant part of whey is used to produce permeates and protein concentrates, in developing countries, whey is usually disposed into water streams, thus creating severe water pollution. However, whey can be converted into valuable products such as ethanol, and β-galactosidase that has seen growing demand in the manufacturing of lactose-free products (Kokkiligadda et al. 2016; Silva et al. 2010).

Subsequent treatment of this organic waste with β-galactosidase can convert it into readily available substrates for cell cultivation (Prashar et al. 2016). Moreover, high-functioning whey proteins, such as lactalbumin, can be recovered through ultrafiltration and further hydrolyzed to produce several pharmaceutical intermediates (Domingues et al. 2005). A study conducted in 2008 reported on the production of β-galactosidase from whey and cauliflower waste. Supplementing whey with cauliflower waste not only increased the enzyme production, but it also decreased the lactose concentration which is responsible for the increase of BOD. Hence, their study confirmed that both these byproducts can be efficiently used to produce for β-galactosidase enzyme on commercial scale.

Another important application of β-galactosidase is lactose hydrolysis which converts whey lactose into a number of suitable products such as sweet syrups that are used in bakery and confectionary industry. β-Galactosidases from fungal sources are reported to be thermostable, and hence, they hydrolyze about 75% of whey lactose. Furthermore, fungal β-galactosidases still retain 70% of activity at the end of the reaction (Batsalova et al. 1987).

Studies were conducted to determine the appropriate conditions to produce β-galactosidase from whey permeates. Streptococcus thermophiles and lactobacillus delbrueckii were used to produce β-galactosidase using a medium enriched with whey and corn liquor. These experiments showed a high enzyme activity. Experiments were also conducted to produce ethanol from cheese whey. The results showed that ethanol was produced using the pure culture of K. marxianus on cheese whey.

Production of galacto-oligosaccharides

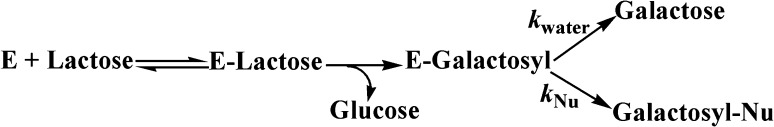

Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) are produced from β-galactosidase by the transglycosylation activity during the hydrolysis of lactose; hence, it is crucially important for the human health. GOS are used as an ingredient in the prebiotics food. The range of oligosaccharide varies between 1 and 45% in GOS that further depends on the total amount of saccharides and source of enzyme. GOS are nondigestible prebiotics that aid to modify intestinal microflora for human health and also promote the growth of useful bacteria in the intestine such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species. Due to acidic conditions, GOS can be stored for longer period of time at room temperature and can be applied to a variety of products without any decomposition (Pazur 1953). Figure 1 depicts the synthetic reaction of galacto-oligosaccharides. The figure shows the β-galactosidase being used during the synthesis of GOS.

Fig. 1.

Reaction showing the synthesis of galacto-oligosaccharides. E β-galactosidase, Nu nucleophil-saccharide, k reaction constant

All oligosaccharides are prepared from mono- and disaccharides via transglycosylation or via polysaccharide hydrolysis. There are three steps involved in the production of oligosaccharide: (i) the release of glucose residue leaving the complex enzyme galactosyl residue for further reaction. (ii) The transfer of this complex to an acceptor that contains hydroxyl group such as saccharides or water molecules. Low concentration of lactose in solution will stimulate the water molecule to act as an acceptor and produce galactose. (iii) Lactose in solution containing high lactose concentration, acts as an acceptor and binds this complex ultimately leads to produce galactosyl-oligosaccharides which is the final step of this reaction (Aronson 1952).

Currently, most of the research is focused on the isolation of microorganisms that produce improved quality of β-galactosidase and ultimately improved GOS (Prenosil et al. 1987). Table 3 enlists the microorganisms that were previously investigated in the production of GOS. GOS production using β-galactosidase from B. longum BCRC 15708 has also been reported (Hsu et al. 2007). The action of this enzyme on lactose produced two types of GOSs: trisaccharides (the major GOS) and tetrasaccharides. The study further reported an increase in GOS production with the increase in lactose concentration. Similarly, Bacillus species were also investigated in the GOS production. An increased GOS production was observed when the enzyme was mixed with glucose oxidase. Recombinant β-galactosidase was also used to produce GOS from B. infantis in Pichia pastori expression system (Mahdian et al. 2016; Jung and Lee 2008). The conversion rates of transgalactosylation and lactose were about 25.2 and 83%, respectively, with the maximum GOS yield of 40.6%. This GOS syrup was reported to contain 5.06% lactose, 8.76% monosaccharaides, and 13.43% GOS.

Table 3.

Production of GOS from β-galactosidase-producing microorganisms

| β-Galactosidase-producing microorganisms | Production of GOS and byproducts | References |

|---|---|---|

| B. longum BCRC 15708 | Two types of GOS: trisaccharides and tetrasaccharides Lactose Glucose Galactose |

Hsu et al. (2007) |

| P. expansum F3 | GOS production Glucose Galactose |

Li et al. (2008) |

| B. infantis | GOS production Lactose Monosaccharides |

Barile et al. (2009) |

| L. bulgaricus | Sialyllactose | Iqbal et al. (2010) |

Human milk contains GOS that increase the number of bifidobacteria in the small intestine of a breast-fed infant. Due to their bifidogenic activity, these GOS reduce the number of pathogenic bacteria. Therefore, companies that deal with the production of infant food now include GOS in their milk- and cereal-based food products (Matto and Husain 2006). Since human body lacks the enzyme required for hydrolyzing β-linkages, these GOS act as soluble fibers, and are fermented by the colonic flora residing in large intestine. The end-products of this fermentation are short-chain fatty acids that decrease the pH of feces. Moreover, the overall acidic environment of the stomach inhibits the formation of pathogenic bacteria. Since these GOS cannot be digested by mouth bacteria, for example, Streptococcus mutants, they do not contribute to developing cariogenicity (Matioli et al. 2003). A wide variety of health benefits are related to oligosaccharides such as anti-carcinogenic effect, reduction of serum cholesterol levels, which occurs when oligosaccharides bind with cholesterol in small intestine; they are also known to improve liver function (Nakagawa et al. 2003). Hence, there has been a significant increase in public demand to produce cost-effective oligosaccharides and GOS. Currently, GOS are being used in various applications such as cosmetics, low calorie sweeteners, soft drinks, cereals, baby food, and powdered milk (Nagy et al. 2001).

Conclusion

β-Galactosidase is one of the industrially important enzymes catering to a wide range of nutritional, food-processing, and environmental applications. Further research on this enzyme will help address the issues related to food and other related industries. Production of novel galacto-oligosaccharides has paved the way for developing prebiotics supplements. It is hoped that the regular use of this enzyme in dairy whey will reduce the water pollution and will produce valuable byproducts such as ethanol and sweet syrup. Hence, β-galactosidase can be used for multitude of applications in various industries.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Author declares that no conflict of interest exists.

Contributor Information

Shaima Saqib, Email: shaimasaqib@hotmail.com.

Attiya Akram, Email: attia.akram73@yahoo.com.

Sobia Ahsan Halim, Phone: +(92) 42 99203781-84, Email: sobia.ahsan@kinnaird.edu.pk, Email: sobiahal@gmail.com.

Raazia Tassaduq, Email: r384@hotmail.com.

References

- Aronson M. Transgalactosidation during lactose hydrolysis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1952;39:370–378. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(52)90346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barile D, Tao N, Lebrilla CB, Coisson JD, Arlorio M, German JB. Permeate from cheese whey ultrafiltration is a source of milk oligosaccharides. Int Dairy J. 2009;19:524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batsalova K, Kunchev K, Popova Y, Kozhukharova A, Kirova N. Hydrolysis of lactose by β-galactosidase immobilized in polyvinylalcohol. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1987;26:227–230. doi: 10.1007/BF00286313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boon MA, Janssen A. Effect of temperature and enzyme origin on the enzymatic synthesis of oligosaccharides. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2000;26:271–281. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(99)00167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borglum G, Sternberg MZ. Properties of a fungal lactase. J Food Sci. 1972;37:619–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1972.tb02707.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandão RL, Nicoli JR, Figueiredo AF. Purification and characterization of a beta-galactosidase from Fusarium oxysporum. J Dairy Sci. 1987;70:1331–1337. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(87)80152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrara CR, Rubiolo AC. Immobilization of β-galactosidase on chitosan. Biotechnol Prog. 1994;10:220–224. doi: 10.1021/bp00026a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Champluvier B, Kamp HE, Rouxhet PG. Immobilization of β-galactosidase retained in yeast: adhesion of the cells on a support. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1988;27:464–469. doi: 10.1007/BF00451614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corral JM, Banuelos O, Adrio JL, Velasco J. Cloning and characterization of a beta-galactosidase encoding region in Lactobacillus coryniformis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;73:640–646. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0510-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingues L, Lima N, Teixeira JA. Aspergillus niger β-galactosidase production by yeast in a continuous high cell density reactor. Process Biochem. 2005;40:1151–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2004.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Gindy A. Production, partial purification and some properties of β-galactosidase from Aspergillus carbonarius. Folia Microbiol. 2003;48:581–584. doi: 10.1007/BF02993462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felicilda-Reynaldo RF, Kenneally M. Digestive enzyme replacement therapy: pancreatic enzymes and lactase. Medsurg Nurs. 2016;25:182–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francesconi CF, Machado MB, Steinwurz F, Nones RB, Quilici FA, Catapani WR, Miszputen SJ, Bafutto M. Oral administration of exogenous lactase in tablets for patients diagnosed with lactose intolerance due to primary hypoplactasia. Arq Gastroenterol. 2016;53:228–234. doi: 10.1590/S0004-28032016000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosová Z, Rosenberg M, Gdovin M, Sláviková L, Rebroš M. Production of d-galactose using β-galactosidase and Saccharomyces cerevisiae entrapped in poly (vinylalcohol) hydrogel. Food Chem. 2009;116:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haider T, Husain Q. Preparation of lactose free milk by using ammonium sulphate fractionated proteins from almonds. J Sci Food Agric. 2007;87:1278–1283. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haider T, Husain Q. Calcium alginate entrapped preparations of Aspergillus oryzae beta galactosidase: its stability and applications in the hydrolysis of lactose. Int J Biol Macromol. 2007;41:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CA, Lee SL, Chou C. Enzymatic production of galactooligosaccharides by β-galactosidase from Lactobacillus pentosus purification characterization and formation of galacto-oligosaccharides from Bifidobacterium longum BCRC 15708. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:2225–2230. doi: 10.1021/jf063126+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber RE, Kurz G, Wallenfels K. A quantitation of the factors which affect the hydrolase and trangalactosylase activities of β-galactosidase (E. coli) on lactose. Biochemistry. 1976;15:1994–2001. doi: 10.1021/bi00654a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ianiro G, Pecere S, Giorgio V, Gasbarrini A, Cammarota G. Digestive enzyme supplementation in gastrointestinal diseases. Curr Drug Metab. 2017;17:187–193. doi: 10.2174/138920021702160114150137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal S, Nguyen TH, Nguyen TT, Maischberger T, Haltrich D. β-Galactosidase from Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1: biochemical characterization and formation of prebiotic galacto-oligosaccharides. Carbohydr Res. 2010;345:1408–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung SJ, Lee BH. Production and application of galacto-oligosaccharides from lactose by a recombinant β-galactosidase of Bifidobacterium infantis overproduced by Pichia pastoris. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2008;17:514–518. [Google Scholar]

- Karasova P, Spiwok V, Mala S, Kralova B, Russell NJ. Beta-galactosidase activity in psychrophic microorganisms and their potential use in food industry. Czech J Food Sci. 2002;20:43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi S, Khayati G, Faezi-Ghasemi M. β-Galactosidase production by Aspergillus niger ATCC 9142 using inexpensive substrates in solid-state fermentation: optimization by orthogonal arrays design. Iran Biomed J. 2016;20:287–294. doi: 10.22045/ibj.2016.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkiligadda A, Beniwal A, Saini P, Vij S. Utilization of cheese whey using synergistic immobilization of β-galactosidase and Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells in dual matrices. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2016;179:1469–1484. doi: 10.1007/s12010-016-2078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Xia M, Lu Y. Production of non-monosaccharide and high-purity galactooligosaccharides by immobilized enzyme catalysis and fermentation with immobilized yeast cells. Process Biochem. 2008;43:896–899. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2008.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lukito W, Malik SG, Surono IS, Wahlqvist ML. From ‘lactose intolerance’ to ‘lactose nutrition’. Asian Pac J Clin Nutr. 2015;24:S1–S8. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2015.24.s1.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdian SMA, Karimi E, Tanipour MH, Parizadeh SMR, Glayour-Mobarhan M, Bazaz MM, Mashkani B. Expression of a functional cold active β-galactosidase from Planococcus sp-L4 in Pichia pastoris. Protein Expr Purif. 2016;125:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney RR. Enzymes exogenous to milk in dairy, β-d-galactosidase. Encycl Dairy Sci. 2003;2:907–914. [Google Scholar]

- Matioli G, Mores FFD, Zanin GM. Operated stability and kinetics of lactose hydrolysis by β galactosidase from Kluyveromyces fragilis. Acta Scientiarum Health Sci. 2003;25:7–12. doi: 10.4025/actascihealthsci.v25i1.2244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matto M, Husain Q. Entrapment of porous and stable concanavalin A-peroxidase complex into hybrid calcium alginate-pectin gel. J Clin Technol Biotechnol. 2006;81:1316–1323. doi: 10.1002/jctb.1540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy Z, Kiss T, Szentirmai A, Biró S. Beta-galactosidase of Penicillium chrysogenum: production, purification, and characterization of the enzyme. Protein Expr Purif. 2001;21:24–29. doi: 10.1006/prep.2000.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Fujimoto Y, Uchino M, Miyaji T, Takano K, Tomizuka N. Isolation and characterization of psychrophiles producing cold-active beta-galactosidase. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2003;37:154–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panesar R, Panesar PS, Singh RS, Bera MB. Production of lactose-hydrolyzed milk using ethanol permeabilized yeast cells. Food Chem. 2007;101:786–790. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.02.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pazur JH. The enzymatic conversion of lactose into galactosyl oligosaccharides. Science. 1953;117:355–356. doi: 10.1126/science.117.3040.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivarnik LF, Senecal AG. Hydrolytic and transgalactosylic activities of commercial beta-galactosidase (lactase) in food processing. Adv Food Nutr Res. 1995;38:1–102. doi: 10.1016/S1043-4526(08)60083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prashar A, Jin Y, Mason B, Chae M, Bressler DC. Incorporation of whey permeate, a dairy effluent, in ethanol fermentation to provide a zero waste solution for the dairy industry. J Dairy Sci. 2016;99:1859–1867. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenosil JE, Stuker E, Bourne JR. Formation of oligosaccharides during enzymatic lactose: part I: state of art. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1987;30:1019–1025. doi: 10.1002/bit.260300904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe MG, Zhong Y, Huang C, Harmsen HJ, Raangs GC, Antoine JM, Welling GW, Vonk RJ. Effects of yogurt and bifidobacteria supplementation on the colonic microbiota in lactose intolerant subjects. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;104:595–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MV, Dutta SM. Lactase activity of microorganisms. Folia Microbiol. 1978;23:210–215. doi: 10.1007/BF02876581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez ÁP, Leiro RF, Trillo MC, Cerdán ME, Siso MIG, Becerra M. Secretion and properties of a hybrid Kluyveromyces lactis–Aspergillus niger β-galactosidase. Microb Cell Fact. 2006;5:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-5-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy I, Gupta MN. Lactose hydrolysis by lactozym™ immobilized on cellulose beads in batch and fluidized bed modes. Process Biochem. 2003;39:325–332. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(03)00086-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seddigh S, Darabi M. Comprehensive analysis of beta-galactosidase protein in plants based on Arabidopsis thaliana. Turk J Biol. 2014;38:140–150. doi: 10.3906/biy-1307-14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla TP, Wierzbicki LE. Beta-galactosidase technology: a solution to the lactose problem. Food Sci Nutr. 1975;21:325–356. [Google Scholar]

- Silanikove N, Leitner G, Merin U. The interrelationships between lactose intolerance and the modern dairy industry: global perspectives in evolutional and historical backgrounds. Nutrients. 2015;7:7312–7331. doi: 10.3390/nu7095340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva AC, Guimarães PMR, Teixeira JA, Domingues L. Fermentation of deproteinized cheese whey powder solutions to ethanol by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae: effect of supplementation with corn steep liquor and repeated-batch operation with biomass recycling by flocculation. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;37:973–982. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0748-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitanggang AB, Drews A, Kraume M. Recent advances on prebiotic lactulose production. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;32:154. doi: 10.1007/s11274-016-2103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DL, Gross KC. A family of at least seven β-galactosidase genes is expressed during tomato fruit development. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:1173–1184. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.3.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenplas Y. Lactose intolerance. Asian Pac J Clin Nutr. 2015;24:S9–S13. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2015.24.s1.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou QZK, Chen XD. Effects of temperature and pH on the catalytic activity of the immobilized β-galactosidase from Kluyveromyces lactis. Biochem Eng J. 2001;9:33–40. doi: 10.1016/S1369-703X(01)00118-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]