Abstract

Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) markers were used to assess the genetic diversity among a collection of 52 sesame accessions representing different geographical environments, including eight Saudi landraces. A combination of seventeen primers generated a high number of alleles (365) with 100% polymorphism. The polymorphic information content (PIC) and primer discrimination power (DP) recorded overall means of 0.88 and 5.88, respectively. Genetic similarity values based on Jaccard coefficients ranged from 0.12 to 0.49, with an average similarity value of 0.30, indicating both high genetic distance and a wide genetic basis of the investigated accessions. The unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) dendrogram grouped 48 of 52 accessions into seven main clusters, and five accessions failed to form clusters and were separated individually. However, subclusters separated the accessions and, considering the relatedness of accessions and their geographical origin, formed distinct diversity among groups. Saudi landraces showed the widest genetic basis compared with other introduced accessions that were distributed throughout the dendrogram, indicating that agro-ecological zones were indistinguishable by cluster analysis. SRAP analysis revealed a high degree of genetic polymorphism in sesame accessions investigated and showed weak association between geographical origin and SRAP patterns. This wide genetic variability should be considered for sesame breeding programs.

Keywords: Sesamum indicum, Genetic diversity, Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP), Saudi sesame landraces

Introduction

Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) is a member of the Pedaliaceae family (Ashri 1998) and order Tubiflorae (Nayar 1976). It is one of the oldest crops in the world and has been cultivated in Asia for over 5000 years (Bisht et al. 1998). The crop has early origins in East Africa and India (Nayar and Mehra 1970) and the cultivated sesame is indigenous to Africa (Weiss 2000), but the crop was initially domesticated on the Indian subcontinent (Bedigian 2003). However, according to Rheenen (1980), Africa is lacking in different forms of the cultivated S. indicum but is rich in other species of the genus Sesamum, while the opposite holds true for India. In Africa, 18 species were found to be endemic, of which only two species are reported in India and four in Sudan. With an oil content of 44–58%, sesame seeds are an important source of oil, as well as protein (18–25%) and carbohydrates (13.5%) (Bedigian et al. 1985), and are traditionally consumed directly.

Three cytogenetic groups in sesame have been defined of which the cultivated S. indicum, S. alatum, S. capense, S. schenckii, and S. malabaricum consist of 2n = 26; S. prostratum, S. laciniatum, S. angolense, and S. angustifolium consist of 2n = 32, while S. radiatum, S. occidentale, and S. schinzianum belong to 2n = 64 and are usually self-pollinated. The cross-compatibility among these species is limited due to the differences in chromosomal numbers. Therefore, it has been difficult to transfer desirable characteristics from wild relatives into cultivated sesame (Carlsson et al. 2008). There are plentiful varieties and ecotypes of sesame adapted to various ecological conditions (Nzikou et al. 2010). Tropical and temperate climatic conditions with stored soil moisture and minimal irrigation or rainfall may produce high-quality yields under high temperatures (Bennet 2011). Temperatures of more than 40 °C affect fertilization and seed set in sesame crops (Weiss 1971).

Characterization and evaluation of genetic diversity in sesame are considered important for germplasm conservation and utilization in breeding programs. Genetic diversity can be characterized using morphological traits or molecular markers. Molecular marker technologies have recently become the main method of analyzing plant genetic diversity and the genetic basis of particular traits, since these markers provide abundant information, are highly efficient, and unlike morphological data, are not sensitive to environmental factors. Various marker systems have been used to study the genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships among sesame genotypes, including microsatellite markers, or simple sequence repeats (SSRs) (Cho et al. 2011; Wei et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2007, 2010); inter-simple sequence repeats (ISSR) (Kumar and Sharma 2011); amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) (Laurentin and Karlovsky 2007); and SRAP (Zhang et al. 2012b, Zhang et al. 2011, Zhang et al. 2010, Zhang et al. 2007). SRAP is an efficient marker system technique for the characterization of genetic diversity because it possesses a high degree of reproducibility and discriminatory power, simplicity, reasonable throughput rate, discloses numerous codominant markers, allows easy isolation of bands for sequencing more reproducible than RAPDs and is easier to assay than AFLPs and, most importantly, it targets open reading frames (Li and Quiros 2001).The present study aimed to assess genetic variability among sesame genotypes collected from different ecological regions using sequence-related amplified polymorphism markers.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Seeds of fifty-two accessions of sesame (Sesame indium L.) collected from Yemen, Pakistan, Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia were used in this study. Theses accessions were collected and conserved in seed gene banks representing sesame genetic resources for each region. The list of sesame accessions and their origin is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

List and origin of sesame accessions used for the current study

| No. | Genotype code | Origin | Serial | Varieties code | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 115008 | Yemen | 27 | 19587 | Pakistan |

| 2 | 115038 | Yemen | 28 | 19591 | Pakistan |

| 3 | 115056 | Yemen | 29 | 19602 | Pakistan |

| 4 | 115057 | Yemen | 30 | 19612 | Pakistan |

| 5 | 115058 | Yemen | 31 | 19613 | Pakistan |

| 6 | 115059 | Yemen | 32 | 19617 | Pakistan |

| 7 | 115060 | Yemen | 33 | 19628 | Pakistan |

| 8 | 115061 | Yemen | 34 | 19636 | Pakistan |

| 9 | 115062 | Yemen | 35 | Shandaweel 3-1 | Egypt |

| 10 | 115064 | Yemen | 36 | Mahaly 222 | Egypt |

| 11 | 115065 | Yemen | 37 | M3A4 | Egypt |

| 12 | 115068 | Yemen | 38 | Shandaweel 3-2 | Egypt |

| 13 | 115069 | Yemen | 39 | RH1F8 | Egypt |

| 14 | 115070 | Yemen | 40 | 497M | Egypt |

| 15 | 115075 | Yemen | 41 | Jordan 107 | Jordan |

| 16 | 115077 | Yemen | 42 | Jordan 108 | Jordan |

| 17 | 115079 | Yemen | 43 | 115071 | Yemen |

| 18 | Sardod-1 | Yemen | 44 | 253 | Saudi Arabia |

| 19 | Sardod-2 | Yemen | 45 | 279 | Saudi Arabia |

| 20 | Koud 94 | Yemen | 46 | 441 | Saudi Arabia |

| 21 | 19531 | Pakistan | 47 | 115067 | Yemen |

| 22 | 19532 | Pakistan | 48 | 517 | Saudi Arabia |

| 23 | 19551 | Pakistan | 49 | 951 | Saudi Arabia |

| 24 | 19560 | Pakistan | 50 | 168 | Saudi Arabia |

| 25 | 19570 | Pakistan | 51 | 697 | Saudi Arabia |

| 26 | 19584 | Pakistan | 52 | 312 | Saudi Arabia |

DNA extraction

DNA extraction was carried out using a modified SDS protocol (Al-Faifi et al. 2013). The leaf sample was grinded to a fine powder and 800 µl of extraction buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 8.0; 50 mM EDTA, pH 8.0; 1.4 M NaCl; 2% (W/V) SDS; 2% (W/V) PVP-40; 0.1% (v/v) β-mercapto-ethanol) was added and mixed and then incubated at 65 °C for 30 min. An equal volume (800 µL) of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1 v/v) was added for protein precipitation. The samples were centrifuged at 17,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C. DNA was precipitated using ice-cold isopropanol, and the pellet was washed using 80% ethanol. The quality and concentration of extracted DNA were detected using 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry using NanoDrop 2000 (Fisher Scientific, USA). Dilution with TE was carried out, and DNA concentration was adjusted to 50 ng/µL.

Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) markers

SRAP-PCR amplification was performed following the methods of Ammar et al. (2015). The PCR reaction was performed in 20 µL volume containing 1 × GoTaq Green Master Mix (Cat. No. M7123, Promega Corporation, Madison, USA), 0.25 µM from each of the forward and reverse primers, 50 ng template DNA, and nuclease-free water up to 20 µL. The forward primers were 50 end-labeled with FAM dye. Amplification was carried out on a TC-5000 thermal cycler (Bibby Scientific, UK) as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min followed by five cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 35 °C for 1 min and elongation at 72 °C for 1 min. In the remaining 30 cycles, the annealing temperature was increased to 50 °C for 1 min with a final extension step at 72 °C for 15 min. Out of 100 SRAP primer combinations, 17 showing consistently reproducible polymorphisms were selected and used to analyze the genotypes (Table 2). For electrophoresis, 1 μL of the PCR-amplified product was mixed with 0.5 μL of the GeneScan 500 LIZ size standard (Applied Biosystems P/N 4322682) and 8.5 μL of Hi-Di Formamide (Applied Biosystems P/N 4311320). The mixture was denatured and loaded on the 16-capillary system of the Applied Biosystems 3130xl Genetic Analyzer.

Table 2.

SRAP primer sequence utilized for polymorphism

| No. | Primer combination | Forward primers | Reverse primers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SRAP6/SRAP6 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGACC | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTAGC |

| 2 | SRAP9/SRAP2 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGTCC | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTAAT |

| 3 | SRAP2/SRAP28 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGAGC | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTTGA |

| 4 | SRAP6/SRAP28 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGACC | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTTGA |

| 5 | SRAP2/SRAP16 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGAGC | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTGAC |

| 6 | SRAP2/SRAP6 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGAGC | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTAGC |

| 7 | SRAP3/SRAP28 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGAGC | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTTGA |

| 8 | SRAP9/SRAP22 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGTCC | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTGTC |

| 9 | SRAP7/SRAP19 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGAAG | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTGGA |

| 10 | SRAP7/SRAP24 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGAAG | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTTAC |

| 11 | SRAP12/SRAP22 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGTAG | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTGTC |

| 12 | SRAP4/SRAP28 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGAGA | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTTGA |

| 13 | SRAP3/SRAP15 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGACA | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTGAA |

| 14 | SRAP6/SRAP11 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGACC | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTCAG |

| 15 | SRAP7/SRAP25 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGAAG | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTTAG |

| 16 | SRAP11/SRAP28 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGTAG | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTTGA |

| 17 | SRAP1/SRAP28 | 5-TGAGTCCAAACCGGATA | 5-GACTGCGTACGAATTTGA |

Data analysis

SRAP fragment analysis was performed with the GeneMapper Analysis Software v3.7 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and the data were assembled in binary format (allele presence (1) or (0) for absence). The threshold for fragment calling was set at 200 relative fluorescence units (rfu), so that any peaks at 200 rfu or higher were assigned a (1) and those that were lower were assigned a (0). Fragment analysis was carried out for fragment sizes in the range of 100–500 bp. Loci with band frequencies of higher than 1 − (3/N), with N = number of individuals sampled, were deleted to account for the estimation bias by overestimating parameters by as much as 5%, especially with small sample sizes (Lynch and Milligan 1994; Alexander et al. 2004). Data generated from SRAP analysis were analyzed using the Jaccard similarity coefficient (Jaccard 1908). These similarity coefficients were used to construct a dendrogram using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic average (UPGMA) employing the PAST3 program. The polymorphism information content (PIC) for each primer was calculated to estimate its allelic variation as follows: , where Pij is the frequency of the ith allele for marker j and the summation extends over n alleles, calculated for each SRAP marker (Anderson et al. 1993). Discrimination power was calculated by dividing the number of polymorphic alleles amplified for each primer by the total number of polymorphic alleles obtained (Khierallah et al. 2011).

Results

Ninety-six primer pair combinations were screened on six accessions selected from different resources to study the ability of primers to amplify DNA fragments. The characteristics of the 17 primers combination are listed in Table 2. These primers showed good amplification and were further used to generate alleles across all accessions. The primers generated 365 alleles (amplified fragments across the accessions) ranging from four alleles for primer pair (14) to 39 for (15) with an average of 21.5 alleles per primer pair combination. All primers showed 100% polymorphism percentage. Primers produced high numbers of bands across accessions; in total, they generated 5807 bands ranging from 58 bands for primer pair combinations (14) to 712 for (8) with an average of 341.6 bands per primer pair combination across accessions. Eight primers generated high numbers of bands across accessions and also generated higher numbers of alleles than the overall average. The number of alleles and bands across accessions generated by these primers ranged from 27 alleles with 455 bands for primer combination (6) to 39 alleles and 683 bands for primer combination (15), in addition to the presence of another combination (8) which produced 38 alleles and 712 bands across accessions. The average number of bands per primer combination ranged from 1.12 for primer (14) to 13.69 for primer (8) with an overall average of 6.57 bands per primer pair combination across accessions. The polymorphic information content (PIC) recorded for each primer combination ranged from 0.63 for primer combination (14) to 0.97 for primer combination (8). The overall mean for PIC values was 0.88, and 11 out of 17 primer combinations exceeded this value. Primer discrimination power (DP) ranged from 1.10 for primer combination (14) to 10.68 for primer combination (15) with an overall average of 5.88. Eight primers exceeded the overall DP mean, ranging in values from 6.3 to 10.41 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of SRAP primers selected in sesame genetic diversity

| Primer | Total allelesa | Total no. of bandsb | Average bandc | PIC | DP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 | 210 | 4.04 | 0.89 | 4.11 |

| 2 | 18 | 270 | 5.19 | 0.64 | 4.93 |

| 3 | 12 | 134 | 2.58 | 0.83 | 3.29 |

| 4 | 7 | 63 | 1.21 | 0.84 | 1.92 |

| 5 | 15 | 174 | 3.35 | 0.88 | 4.11 |

| 6 | 27 | 455 | 8.75 | 0.95 | 7.40 |

| 7 | 8 | 124 | 2.38 | 0.80 | 2.19 |

| 8 | 38 | 712 | 13.69 | 0.97 | 10.41 |

| 9 | 31 | 547 | 10.52 | 0.95 | 8.49 |

| 10 | 17 | 355 | 6.83 | 0.92 | 4.66 |

| 11 | 36 | 564 | 10.85 | 0.96 | 9.86 |

| 12 | 23 | 335 | 6.44 | 0.95 | 6.30 |

| 13 | 18 | 318 | 6.12 | 0.90 | 4.93 |

| 14 | 4 | 58 | 1.12 | 0.63 | 1.10 |

| 15 | 39 | 683 | 13.13 | 0.96 | 10.68 |

| 16 | 28 | 387 | 7.44 | 0.94 | 7.67 |

| 17 | 29 | 418 | 8.04 | 0.95 | 7.95 |

| Total | 365 | 5807 | – | – | – |

| Average | 21.47 | 341.59 | 6.57 | 0.88 | 5.88 |

| Min | 4 | 58 | 1.12 | 0.63 | 1.10 |

| Max | 39 | 712 | 13.69 | 0.97 | 10.68 |

aTotal number of differently sized SRAP fragments amplified across all 52 accessions

bTotal number of SRAP fragments scored for all accessions

cAverage number of SRAP fragments scored per accessions

Genetic similarity estimates based on Jaccard (1908) similarity coefficients from the SRAP data were used to assess the genetic relatedness among the 52 sesame accessions. Table 1 shows the mean similarity indices for all 52 pairwise combinations. The means ranged from 0.12 between SA 517 and YE 115056 to 0.49 between YE 115068 and PA 19560. All accessions showed an average of similarity of 0.30.

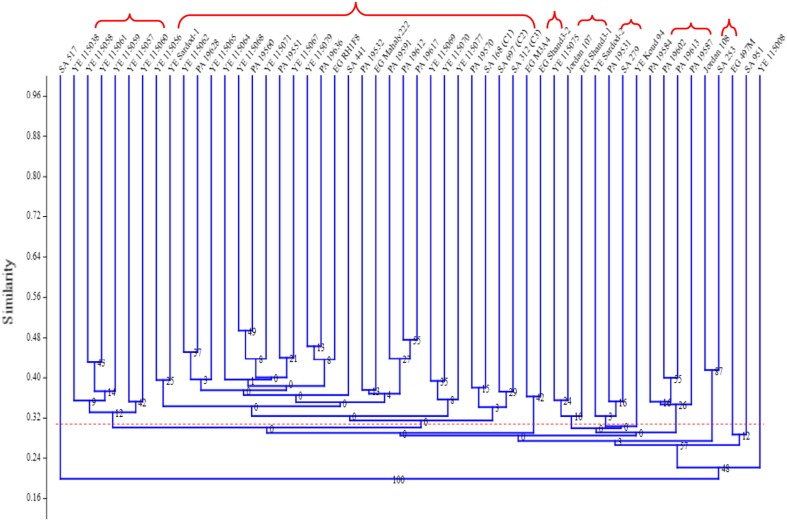

The UPGMA cluster analysis of 52 accessions based on SRAP data showed that at 30% similarity index, which represented the average of all accessions similarities, cutting the dendrogram at this similarity value resulted in seven main clusters and five accessions that failed to make clusters and separated individually (Fig. 1). In the first main cluster, six accessions from Yemen were grouped ranging in similarity from 0.30 to 0.43 with an average of 0.35. The closest genotypes were YE 115058 and YE 115061 with a similarity index value of 0.43, while the most diverse genotypes in this cluster were YE 115038 and YE 115057 with a similarity index value of 0.30. Twelve accessions from Yemen, nine accessions from Pakistan, four accessions from Saudi Arabia, and two accessions from Egypt were grouped in the second cluster ranging in similarity from 0.23 to 0.48 with an average of 0.34. The Pakistani accessions PA 19612 and PA 19617 were the closest in this cluster with a similarity index of 0.48, while the most diverse accessions in this cluster were PA 19591 and SA 312 (C3) with a 0.23 similarity value.

Fig. 1.

Dendrogram produced by Jaccard’s coefficient and the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic average (UPGMA)

Two clusters encompassed two accessions for each, which were two Egyptian accessions EG M3A4 and EG Shand3-2, grouped in one sub- cluster with a similarity value of 0.36, and the in the second cluster was one accession from Jordan 108 and one from Saudi Arabia (SA 253) with a similarity index of 0.42. Two clusters encompassed three accessions for each with different origins. Instead, there was one accession from Yemen, one from Jordan, and one from Egypt, with an average similarity of 0.33 values was grouped. In the second cluster, there was one accession from Yemen, one from Pakistan, and one from Saudi Arabia, showing an average similarity value of 0.33. In the seventh cluster, there were four accessions from Pakistan that were grouped with similarity values ranging from 0.34 between PA 19587 and PA 19613 to 0.4 between PA 19602 and PA 19613.

Five accessions, which were two Saudi (SA 517 and SA 951), two Yemeni (YE Koud94 and YE 115008), and one Egyptian (EG 497 M), failed to form any cluster and individually separated and were considered the most diverse accessions.

Discussion

The large genetic variability present in Sesamum indicum L. should be considered when planning for conservation strategies and breeding programs utilizing this variability. Both morphological and molecular studies confirmed this. DNA-based markers including ISSR, AFLP, SSR, and SRAP have been used in studying genetic variability in sesame.

In the present study, SRAP was successfully applied on sesame genetic diversity in a representative sample of the collection of 52 sesame accessions representing different geographical environments. The combination of 17 primers generated a higher number of alleles (365) with 100% polymorphism, indicating the suitability of selected primers for detecting genetic variability among the accessions tested. Although differences in both the number of primers and accessions used in this study compared with other studies, the polymorphisms were higher than those reported by Zhang et al. (2010, 2011, 2012b), who also reported an equivalent amount of polymorphic alleles per locus in 67 sesame cultivars. In contrast to these findings, Zhang et al. (2011) recorded an average of 14.5 and 12.5 polymorphic alleles per primer combination, compared with 21.6 polymorphic alleles in this study. In another study using AFLP markers, Laurentin and Karlovsky (2006) recorded 93% polymorphism in a collection of 32 sesame accessions; however, in contrast to these findings, Ali et al. (2007) have found low genetic polymorphism (35%) among 96 accessions of sesame collected from different geographical areas. Using ISSR markers, Kumar et al. (2012) have recorded 73% polymorphism and Parsaeian et al. (2011) recorded 76% polymorphism in a collection of morphologically and geographically diverse sesame accessions. However, Kumar and Sharma (2011) recorded 57 and 73% polymorphisms by ISSR and SSR primers, respectively, among 20 commercially cultivated sesame genotypes representing different geographical regions of India. It was found also that low polymorphism (56%) using RAPD and 67% using ISSR markers was present among sesame accessions (Sharma et al. 2009). The higher number of amplified fragments detected in this study associated with higher polymorphism percentages compared with other studies is mainly due to the genotypes, primer combination, used as well as the laser-based detection system in capillary electrophoresis with more extraordinary resolution power than ordinary gel electrophoresis (Ammar et al. 2015) .

The higher values of PIC (range = 0.63–0.97, average = 0.88) and primer discrimination power (DP) (range = 1.10–10.67, average = 5.88) recorded in this study indicated the power of these selected primers for discrimination genetic diversity of the accessions. The results of PIC values in this study exceeded those of Zhang et al. (2012b), who recorded an average of 0.20 in mini-core and 0.18 in Chinese sesame core collection. SRAP primers yielded more than twice the number of polymorphic bands per primer with the highest average polymorphism information content (PIC) in comparative studies including different molecular markers (Robarts and Wolfe 2014), where markers with higher PIC values possessed greater potential to reveal allelic variation. High PIC values were used as selection criteria to develop a mini-core collection of Chinese sesame core collection (Zhang et al. 2012b). PIC was also used to measure informativeness of primer combinations in many crops including soybean, wheat, maize, and different Medicago species. In this study, pairwise genetic similarity indices between all 52 accessions (range = 0.12–0.49, average = 0.30) divided the accessions to seven main clusters. The Jaccard genetic similarity coefficient indicated that genetic relationships were the closest between accessions in group seven (0.34–0.40) and the most distant in the second group (0.23–0.42). Accessions in group seven were introduced from Pakistan, while those in the second group were introduced from different geographical regions.

Three out of seven clusters revealed association between accessions and geographical regions. For instance, all accessions in the first group were introduced from Yemen, accessions in cluster seven were from Pakistan, and two accessions from Egypt formed the third cluster. The lack of clear division among sesame accessions based on their geographical origin in the dendrogram shows enlargement of genetic diversity. The results of this study agree with others in showing that geographical separation did not generally result in greater genetic distance. This may be because sesame has been introduced into many countries, and materials from widely separate locations have been exchanged. Thus, this collection holds diverse germplasm within it that can be used as sources of useful traits for sesame improvement (Kim et al. 2002). In this study, the local accessions (landraces) were distributed throughout the dendrogram indicating that agro-ecological zones were indistinguishable by cluster analysis, which agreed with other studies in showing that geographical separation did not generally result in greater genetic distance (Laurentin and Karlovsky 2006). In the largest cluster (cluster 2), which contributed more than 50% of the total accessions, 27 accessions were grouped in subclusters according to their geographical region or tended to individually separated. For example, four subclusters encompassed nine accessions from Yemen, one subcluster encompassed two local accessions, and another subcluster encompassed three accessions from Pakistan. The local accessions (eight accessions from KSA) tended to group together in the same subcluster or formed individual clusters in the second main cluster.

To some extent, our results were consistent with those of Zhang et al. (2011), Wei et al. (1994), and Zhao and Liu (2005), who showed no obvious regularity clustering in different types of cultivars and cultivars with different origins, which could be ascribed to the frequent exchanges of sesame cultivars and limited breeding parents in China. Pandey et al. (2015) have found that genotypes belonging to the same geographical area did not always occupy the same cluster. High genetic diversity exists among cultivar lines and related wild species from various geographical locations were grouped together in the same cluster (Surapaneni et al. 2014). The lack of association between the genetic and geographical regions could be due to extensive gene flow across the geographical regions (Kumar et al. 2012) and exchange of breeding material between farmers. It was found also that geographical separation did not generally result in greater genetic distance. Parsaeian et al. (2011 ) and Zhang et al. (2012a and 2012b) found no association between molecular diversity and geographical distribution and some genotypes from different geographical regions were grouped in the same cluster. The exchange of plant materials across the regions during the history of sesame cultivation along with process of selection and out-crossing could be responsible for the lack of correlation between genetic diversity patterns and geographical distribution. Laurentin and Karlovsky (2006) found no association between geographical origin and AFLP patterns for sesame collection representing five diversity centers (India, Africa, China–Korea–Japan, Central Asia, and Western Asia), suggesting that there was considerable gene flow among diversity centers. A large number of plants should be used to represent future germplasm collection strategies; covering many diversity centers is less important, because each center represents a major part of the total diversity in sesame.

The traditional assumption that selecting genotypes of different geographical origins will maximize the diversity available to a breeding project does not hold for sesame (Laurentin and Karlovsky 2006). Hartings et al. (2008) demonstrated that distribution of genetic diversity within and among populations is a function of the rate of gene flow between populations, and the extent of gene flow in a species depends on the distribution of the habitats it occupies, the size and degree of isolation of its populations, and movement of pollen and seeds between populations. Natural out-crossing might also be responsible for narrowing of genetic diversity and blurring the boundaries of geographic and genetic groupings (Kumar et al. 2012). However, Ali et al. (2007) indicated that close genetic relations between the accessions was determined by geographical origin and AFLP markers. The accessions were clustered mainly corresponding to their geographical origin as well as by morphological characteristics, and these results were also supported by Bedigian (2010), who observed patterns of sesame’s genotypic diversity following geographic lines. Zhang et al. (2010) have concluded that the complexity of geographical and climatic factors, planting systems, and relative importance of the crop in the region could partly account for the higher genetic diversity. Therefore, cultivar improvement was not regarded much, and many old landraces had been cultivated, while the higher genetic diversity could be retained.

Conclusion

Our SRAP-based study on sesame accessions collected from different geographical regions (five countries) found a high level of polymorphism in this DNA-based marker and did not show an association between geographical origin and SRAP patterns. The large number of polymorphic-amplified fragments produced in this study (365), with an average of 21.5 fragments per primer pair indicates that this system is a reliable and powerful tool to evaluate genetic polymorphisms and relationships among sesame accessions. The genetic basis of the main sesame accessions was large in this study; the average genetic distance coefficient of 52 accessions was as high as 0.69 and the genetic basis of KSA landraces was wider than other accessions tested with a value of genetic distance of 0.72. Such information will be useful to determine optimal breeding strategies, and to allow continued progress in sesame breeding. Diverse genetic backgrounds among parental lines provide a large supply for allelic variations that can be used to develop new favorable gene combinations in sesame breeding programs. It is necessary to reinforce the collection and protection of sesame germplasm resources from agro‐ecological zones with higher diversity. Furthermore, genetic distance between parents should be considered for sesame breeding programs.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to Researchers Support Services Unit at King Saud University (KSU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for language editing. Seeds provided by national seeds gene banks from Jordan, Yemen, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia are highly appreciated and acknowledged.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: SAA. Performed the experiments: BHA, AAM, NAM. Analyzed the data: HMM and BHA. Wrote the paper: HMM, SSA. Read, critically edited, and approved: HMM, SSA, SAA and YAR. The final manuscript: HMM, SSA.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander DE, Kaczorowski DJ, Jackson-Fisher AJ, Lowery DM, Zanton SJ, Pugh BF. Inhibition of TATA binding protein dimerization by RNA polymerase III transcription initiation factor Brf1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32401–32406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405782200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Faifi SA, Migdadi HM, Al-doss A, Ammar MH, El-Harty EH, Khan MA, Muhammad JM, Alghamdi SS. Morphological and molecular genetic variability analyses of Saudi lucerne (Medicago sativa L.) landraces. Crop Pasture Sci. 2013;64(2):137–146. doi: 10.1071/CP12271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali GM, Yasumoto S, Seki-Katsuta M. Assessment of genetic diversity in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) detected by amplified fragment length polymorphism markers. Electron J Biotechnol. 2007;10(1):12–23. doi: 10.2225/vol10-issue1-fulltext-16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ammar MH, Alghamdi SS, Migdadi HM, Khan MA, El-Harty EH, Al-Faifi SA. Assessment of genetic diversity among faba bean genotypes using agro- morphological and molecular markers. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2015;22(3):340–350. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J, Churchill G, Autrique J, Tanksley S, Sorrells M. Optimizing parental selection for genetic linkage maps. Genome. 1993;36(1):181–186. doi: 10.1139/g93-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashri A. Sesame breeding. Plant Breed Rev. 1998;16:179–228. [Google Scholar]

- Bedigian D. Evolution of sesame revisited: domestication, diversity and prospects. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2003;50(7):779–787. doi: 10.1023/A:1025029903549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedigian D. Characterization of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) germplasm: a critique. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2010;57(5):641–647. doi: 10.1007/s10722-010-9552-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedigian D, Seigler DS, Harlan JR. Sesamin, sesamolin and the origin of sesame. Biochem Syst Ecol. 1985;13(2):133–139. doi: 10.1016/0305-1978(85)90071-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennet M (2011) Sesame seed: a handbook for farmers and investors. www.agmrc.org/media/cm/sesame_38F4324EE52CB

- Bisht I, Mahajan R, Loknathan T, Agrawal R. Diversity in Indian sesame collection and stratification of germplasm accessions in different diversity groups. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 1998;45(4):325–335. doi: 10.1023/A:1008652420477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson AS, Chanana NP, Gudu S, Suh MC, Were BA. Sesame. Compend Transgenic Crop Plants. 2008;2(6):227–246. doi: 10.1002/9781405181099.k0206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y-I, Park J-H, Lee C-W, Ra W-H, Chung J-W, Lee J-R, Ma K-H, Lee S-Y, Lee K-S, Lee M-C. Evaluation of the genetic diversity and population structure of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) using microsatellite markers. Genes Genom. 2011;33(2):187–195. doi: 10.1007/s13258-010-0130-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartings H, Berardo N, Mazzinelli G, Valoti P, Verderio A, Motto M. Assessment of genetic diversity and relationships among maize (Zea mays L.) Italian landraces by morphological traits and AFLP profiling. Theor Appl Genet. 2008;117(6):831–842. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0823-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard P. Nouvelles recherches sur la distribution florale. Bulletin Société Vaudoise Sciences Naturelles. 1908;44:223–270. [Google Scholar]

- Khierallah H, Bader S, Baum M, Hamwieh A. Assessment of genetic diversity for some Iraqi date palms (Phoenix dactylifera L.) using amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLP) markers. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10(47):9570–9576. doi: 10.5897/AJB11.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Zur G, Danin-Poleg Y, Lee S, Shim K, Kang C, Kashi Y. Genetic relationships of sesame germplasm collection as revealed by inter-simple sequence repeats. Plant Breed. 2002;121(3):259–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0523.2002.00700.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Sharma SN. Comparative potential of phenotypic, ISSR and SSR markers for characterization of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) varieties from India. J Crop Sci Biotechnol. 2011;14(3):163–171. doi: 10.1007/s12892-010-0102-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H, Kaur G, Banga S. Molecular characterization and assessment of genetic diversity in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) germplasm collection using ISSR markers. J Crop Improv. 2012;26(4):540–557. doi: 10.1080/15427528.2012.660563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laurentin HE, Karlovsky P. Genetic relationship and diversity in a sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) germplasm collection using amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) BMC Genet. 2006;7(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurentin H, Karlovsky P. AFLP fingerprinting of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) cultivars: identification, genetic relationship and comparison of AFLP informativeness parameters. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2007;54(7):1437–1446. doi: 10.1007/s10722-006-9128-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Quiros CF. Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP), a new marker system based on a simple PCR reaction: its application to mapping and gene tagging in Brassica. Theor Appl Genet. 2001;103(2–3):455–461. doi: 10.1007/s001220100570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Milligan B. Analysis of population-genetic structure using RAPD markers. Mol Ecol. 1994;3:91–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.1994.tb00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayar N. Sesame: Sesamum indicum (Pedaliaceae) In: Simmonds NW, editor. Evolution of crop plants. London and New York: Long man; 1976. pp. 231–233. [Google Scholar]

- Nayar N, Mehra K. Sesame: its uses, botany, cytogenetics, and origin. Econ Bot. 1970;24(1):20–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02860629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nzikou J, Mvoula-Tsiéri M, Ndangui C, Pambou-Tobi N, Kimbonguila A, Loumouamou B, Silou T, Desobry S. Characterization of seeds and oil of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) and the kinetics of degradation of the oil during heating. Res J Appl Sci Eng Technol. 2010;2(3):227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SK, Das A, Rai P, Dasgupta T. Morphological and genetic diversity assessment of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) accessions differing in origin. Physiol Mol Biol Plant. 2015;21(4):519–529. doi: 10.1007/s12298-015-0322-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsaeian M, Mirlohi A, Saeidi G. Study of genetic variation in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) using agro-morphological traits and ISSR markers. Russ J Genet. 2011;47(3):314–321. doi: 10.1134/S1022795411030136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheenen HAV Genetic resources of sesame in Africa: collection and exploration. Sesame: Status and improvement. In: Proceedings of Expert Consultation, Rome, Italy, 8–12 December 1980. FAO Plant Production and Protection, pp. 29

- Robarts DW, Wolfe AD. Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) markers: a potential resource for studies in plant molecular biology. Appl Plant Sci. 2014;2(7):1400017. doi: 10.3732/apps.1400017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Kumar V, Mathur S. Comparative analysis of RAPD and ISSR markers for characterization of sesame (Sesamum indicum L) genotypes. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol. 2009;18(1):37–43. doi: 10.1007/BF03263293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Surapaneni M, Yepuri V, Vemireddy LR, Ghanta A, Siddiq E. Development and characterization of microsatellite markers in Indian sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) Mol Breeding. 2014;34(3):1185–1200. doi: 10.1007/s11032-014-0109-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Zhang H, Lu F, Wei S. Applications of principal components analysis and genetic distance estimation in sesame breeding programme. Acta Agric Boreal Sin. 1994;9(3):29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wei L-B, Zhang H-Y, Zheng Y-Z, Guo W-Z, Zhang T-Z. Developing EST-derived microsatellites in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) Acta Agron Sin. 2008;34(12):2077–2084. doi: 10.1016/S1875-2780(09)60019-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss E. Castor, sesame and safflower. London: Leonard Hill; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss E. Oilseed crops. United Kingdom: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Zhang H, Guo W, Zheng Y, Wei L, Zhang T. Genetic diversity analysis of Sesamum indicum L. germplasms using SRAP and EST-SSR markers. Acta Agron Sin. 2007;33(10):1696. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y-X, Zhang X-R, Hua W, Wang L-H, Che Z. Analysis of genetic diversity among indigenous landraces from sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) core collection in China as revealed by SRAP and SSR markers. Genes Genom. 2010;32(3):207–215. doi: 10.1007/s13258-009-0888-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y-X, Sun J, Zhang X-R, Wang L-H, Che Z. Analysis on genetic diversity and genetic basis of the main sesame cultivars released in China. Agric Sci China. 2011;10(4):509–518. doi: 10.1016/S1671-2927(11)60031-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Wei L, Miao H, Zhang T, Wang C. Development and validation of genic-SSR markers in sesame by RNA-seq. BMC Genom. 2012;13(1):316. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang X, Che Z, Wang L, Wei W, Li D. Genetic diversity assessment of sesame core collection in China by phenotype and molecular markers and extraction of a mini-core collection. BMC Genet. 2012;13(1):102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-13-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y-Z, Liu H-Y. Genetic distance and heterosis between male sterile lines and core collection in sesame. Chin J Oil Crop Sci. 2005;1:36–40. [Google Scholar]