Abstract

Background and Purpose

The diterpenoids carnosol (CS) and carnosic acid (CA) from Salvia spp. exert prominent anti‐inflammatory activities but their molecular mechanisms remained unclear. Here we investigated the effectiveness of CS and CA in inflammatory pain and the cellular interference with their putative molecular targets.

Experimental Approach

The effects of CS and CA in different models of inflammatory pain were investigated. The inhibition of key enzymes in eicosanoid biosynthesis, namely microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase‐1 (mPGES‐1) and 5‐lipoxygenase (5‐LO) was confirmed by CS and CA, and we determined the consequence on the eicosanoid network in activated human primary monocytes and neutrophils. Molecular interactions and binding modes of CS and CA to target enzymes were analyzed by docking studies.

Key Results

CS and CA displayed significant and dose‐dependent anti‐inflammatory and anti‐nociceptive effects in carrageenan‐induced mouse hyperalgesia 4 h post injection of the stimuli, and also inhibited the analgesic response in the late phase of the formalin test. Moreover, both compounds potently inhibited cell‐free mPGES‐1 and 5‐LO activity and preferentially suppressed the formation of mPGES‐1 and 5‐LO‐derived products in cellular studies. Our in silico analysis for mPGES‐1 and 5‐LO supports that CS and CA are dual 5‐LO/mPGES‐1 inhibitors.

Conclusion and Implications

In summary, we propose that the combined inhibition of mPGES‐1 and 5‐LO by CS and CA essentially contributes to the bioactivity of these diterpenoids. Our findings pave the way for a rational use of Salvia spp., traditionally used as anti‐inflammatory remedy, in the continuous expanding context of nutraceuticals.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed section on Principles of Pharmacological Research of Nutraceuticals. To view the other articles in this section visit http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.v174.11/issuetoc

Abbreviations

- CA

carnosic acid

- CS

carnosol

- 5,12‐DiHETE

5,12‐dihydroxy‐6,8,10,14‐eicosatetraenoic acid

- 5,15‐DiHETE

5,15‐dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- 5‐HEPE

5‐hydroxy‐eicosapentaenoic acid

- 12‐HEPE

12‐hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- 5‐HETE

5‐hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid

- 11‐HETE

11‐hydroxy‐5,8,12,14‐eicosatetraenoic acid

- 12‐HETE

12‐hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- 15‐HETE

15‐hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid

- 5‐HETrE

5‐hydroxyeicosatrienoic acid

- 15‐HETrE

15‐hydroxyeicosatrienoic acid

- 12‐HHT

12‐hydroxyheptadecatrenoic acid

- 9‐HODE

9‐hydroxy‐octadecadienoic acid

- 13‐HODE

13‐hydroxy‐octadecadienoic acid

- 5‐H(P)ETE

5‐hydro(pero)xy‐6,8,11,14‐eicosatetraenoic acid

- LO

lipoxygenase

- mPGES‐1

microsomal PGE2 synthase‐1

- UPLC

Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography

- Salvia spp.

Salvia species

- XP

extra precision

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| Enzymes |

| mPGES‐1, microsomal PGE2 synthase‐1 |

| LOX, lipoxygenase |

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| CA, carnosic acid |

| CS, carnosol |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Southan et al., 2016) or other databases and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 (Alexander et al., 2015).

Introduction

Diterpenoids are secondary metabolites found in higher plants, fungi, and marine organisms, and they are known to display multiple biological activities (Giamperi et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2014). The anti‐inflammatory and analgesic characteristics of some diterpenoids ‐ especially those isolated from plants ‐ have been intensively described, and mainly interfere with the multiple signaling pathways that are deregulated during inflammation and inflammatory pain syndrome, including NF‐κB (Salminen et al., 2008), p38‐MAPK (Kundu et al., 2006) and phosphatidylinositol‐3K (Johnson, 2011).

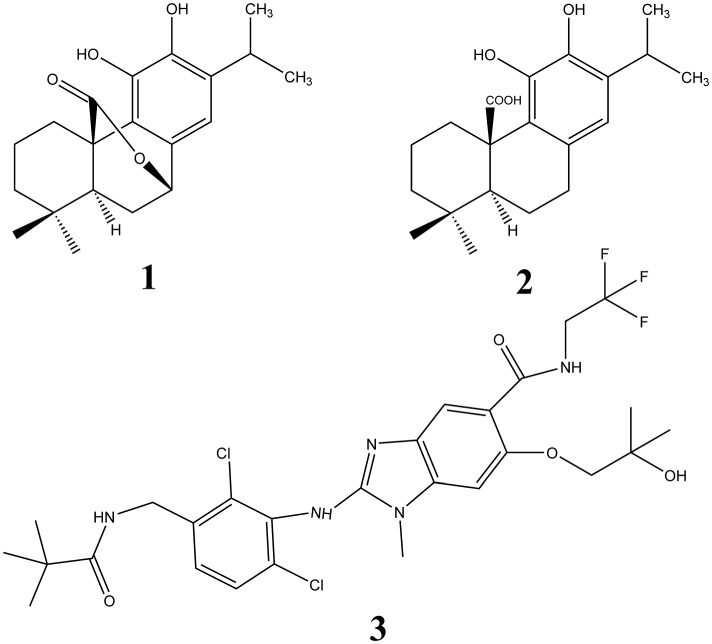

Among the analgesic diterpenoids, much attention has recently been pointed on carnosol (CS) and carnosic acid (CA; Figure 1), which suppress cyclooxygenase (COX)‐2, interleukin‐1β, and tumor necrosis factor‐α expression as well as leukocyte infiltration in inflamed tissues (Mengoni et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2015) and regulate the levels of the inflammatory MMP‐9 and monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1 (MCP‐1) in cell migration (Chae et al., 2012). In addition, molecular targets of CS and CA within the eicosanoid biosynthetic pathways have been revealed, including 5‐lipoxygenase (5‐LO), the key enzyme in the biosynthesis of pro‐inflammatory leukotrienes (Laughton et al., 1991; Poeckel et al., 2008), COX enzymes that initiate prostaglandin (PG) synthesis (Laughton et al., 1991), and microsomal PGE2 synthase (mPGES)‐1 (Bauer et al., 2012) which is the terminal enzyme in pro‐inflammatory PGE2 formation.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of CS (1) and CA (2). Also shown, as compound 3, is the structure of the inhibitor of mPGES‐1, 2‐[[2,6‐bis(chloranyl)‐3‐[(2,2‐dimethylpropanoylamino)methyl]phenyl]amino]‐ 1‐methyl‐6‐(2‐methyl‐2‐oxidanyl‐propoxy)‐ N‐[2,2,2‐tris(fluoranyl)ethyl]benzimidazole‐ 5‐carboxamide.

Contingently, it has been found that Salvia species (spp.) (Labiateae) containing these diterpenoids (Bruna et al., 2006; Villa et al., 2009), could act as a mild analgesic (Mirjalili et al., 2006; Raal et al., 2007). Recent investigations have demonstrated the anti‐nociceptive potential of Salvia officinalis extract and its isolated compound CS in different in vivo models of inflammation (Rodrigues et al., 2012). Subsequently, it has been validated that the hydroalcoholic extract of Salvia officinalis and its constituent CS inhibit formalin‐induced pain and inflammation in mice (Emami et al., 2013).

Furthemore, increasing interest worldwide has been expressed within recent years in the use of bioactive compounds originally present in plants to provide health‐care products (Miyata, 2007; Di Lorenzo et al., 2013). In this context, different plants belonging to Salvia spp. offer considerable potential for the development of healthier foods. Overall, most of their bioactive components, in addition to other important nutritional components such as vitamins and minerals, exhibit anti‐inflammatory and anti‐oxidative properties that could provide a rational for the prevention and/or treatment of inflammatory complications (Maione et al., 2015b).

In light of the ethnobotanical use of Salvia spp. (and their potential application as nutraceuticals) wherein the main constituents are diterpenoids, here we have evaluated potential analgesic activities of the CS and CA in the treatment of pain and inflammation. In more detail, we have used in vivo models of inflammatory and mechanical pain, and successively we have investigated the cellular interference with their molecular targets taking into account the key enzymes involved in the arachidonic acid cascade as mPGES‐1 and 5‐LO.

Methods

In vivo procedures

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the local animal care office (Service for Biotechnology and Animal Welfare of Istituto Superiore di Sanità) and were carried out to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering. Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath and Lilley, 2015). CD‐1 male mice (10–14 weeks of age, 25–30 g of weight) were purchased from Charles River (Milano, Italy) and kept in animal care facility under controlled temperature, humidity and light/dark cycle, and with food and water ad libitum. A total of 66 animals were used for the experiments described here.

Induction and assessment of carrageenan‐induced hyperalgesia

Acute inflammation was induced in the right hind paw by injecting subcutaneously (s.c.) 50 μl of freshly prepared solution of 1% carrageenan. The left paw received 50 μl of saline, which served as control. The response to inflammatory pain was determined by measuring the mechanical nociceptive pressure by the paw pressure test via a commercially available analgesiometer (Ugo Basile, Italy). The apparatus was set up to apply a force of 0‐250 g, increasing from zero. The nociceptive threshold was taken as the end point at which mice vocalized or struggled vigorously (Randall and Selitto, 1957). CS and CA were administrated subcutaneously (s.c.) into the dorsal hind paw of the mice in a dose‐dependent manner (1‐100 μg 20 μl−1) 30 min before 1% carrageenan (50 μl; s.c.) into the dorsal hind paw of the mice, and the pressure threshold was observed at 0.5, 1, 3, and 4 h. The time selection was made based on the preliminary studies. A change in the hyperalgesic state was calculated as a percentage of the maximum possible effect (% MPE) from the formula: [(P2‐P1)/(P0‐P1) × 100], where P1 and P2 were the pre‐ and post‐drug paw withdrawal thresholds respectively, and P0 was the cut‐off (250 g).

Formalin test

The procedure used has been previously described (Colucci et al., 2008). Subcutaneous injection of a dilute solution of formalin (1%, 20 μl/paw) into the mice hind paw evokes nociceptive behavioral responses, such as licking, biting the injected paw or both, which are considered indices for pain. The nociceptive response shows a biphasic trend, consisting of an early phase occurring from 0 to 10 min after the formalin injection, due to the direct stimulation of peripheral nociceptors, followed by a late prolonged phase occurring from 20 to 40 min that reflects the response to inflammatory pain. In light of the results for carrageenan‐induced hyperalgesia, we have selected the dose of 100 μg to test the effect of the two diterpenoids on the formalin test. During the test, the mouse was placed in a Plexiglas observation cage (30 × 14 × 12 cm), 1 h before the formalin administration to allow it to acclimatize to its surroundings. The total time (s) that the animal spent licking or biting its paw during the formalin‐induced early and late phase of nociception was recorded. CS and CA were administrated subcutaneously (s.c.) (100 μg/20 μl) 30 min before formalin injection (20 μl; s.c.).

Activity assay for human recombinant 5‐LO

Human recombinant 5‐LO was expressed in Escherichia coli (E. coli BL21 (DE3)) cells and partially purified by affinity chromatography using an ATP‐agarose column as described (Koeberle et al., (2014). Semi‐purified 5‐LO (1.6 ± 0.2 μg 5‐LO products per μg protein) was diluted in PBS containing EDTA (1 mM) and ATP (1 mM) to a concentration of 0.5 μg mL−1 and immediately pre‐incubated with the test compounds (1 μl in DMSO; final DMSO concentration: 0.1%) for 10 min at 4°C. Samples were pre‐warmed for 30 s at 37°C, and 5‐LO product formation was initiated by addition of CaCl2 (5 μl; in water) and arachidonic acid (5 μl; in methanol) to final concentrations of 2 mM and 20 μM, respectively. The reaction was stopped after 10 min at 37°C by addition of 1 ml ice‐cold methanol. Formed 5‐LO metabolites (all‐trans isomers of LTB4 and 5‐hydro(pero)xy‐6,8,11,14‐eicosatetraenoic acid (5‐H(P)ETE)) were extracted and an aliquot of 50 μl analyzed by reversed phase‐HPLC (RP‐HPLC) as described (Koeberle et al., 2009). Data were normalized to the vehicle control to avoid variations independent of test compounds.

Activity assay for human mPGES‐1

Microsomal preparations of interleukin‐1β‐treated A549 (Homo sapiens lung carcinoma) cells were prepared as previously described (Koeberle et al., 2008) and used as source for mPGES‐1 (Koeberle et al., 2008). Microsomes (2.5–5 μg total protein) in 50 μl potassium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) containing 2.5 mM glutathione were pre‐incubated with the test compounds (1 μl in DMSO; final DMSO concentration: 2%) for 15 min at 4°C. The reaction was started by addition of PGH2 (50 μl in potassium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) containing 2.5 mM glutathione; final concentration: 20 μM) and terminated after 1 min by addition of stop solution (100 μl; 40 mM FeCl2, 80 mM citric acid and 10 μM of 11β‐PGE2 as internal standard). PGE2 was extracted and analyzed by reversed phase‐HPLC as described (Koeberle et al., 2008). Data were normalized to the vehicle control to avoid variations independent of test compounds.

Blood cell isolation and cultivation of cell lines

Human neutrophils and monocytes were freshly isolated from peripheral blood obtained at the Institute for Transfusion Medicine of the University Hospital Jena (Germany) as described (Schaible et al., 2013b). In brief, leukocyte concentrates were obtained from venous blood by centrifugation. Cells were isolated by dextrane sedimentation and centrifugation on Histopaque‐1077 cushions (Sigma‐Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany). Erythrocytes were lysed under hypotonic conditions and neutrophils were recovered by centrifugation. Monocytes were isolated from the fraction of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) by adherence to culture flasks. Washed cells were finally resuspended in PBS pH 7.4 plus 1 mM CaCl2 containing 1 mg/ml glucose (neutrophils) or monocyte medium (RPMI 1640 medium containing L‐glutamine (2 mM) and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml and 100 μg/ml, respectively) supplemented with FCS (5%, v/v; monocytes).

Analysis of the eicosanoid profile of activated human neutrophils and monocytes

Neutrophils (5 × 106 cells ml−1) in PBS pH 7.4 plus 1 mM CaCl2 containing 1 mg·mL−1 glucose were pre‐incubated with test compounds (1 μl in DMSO; final DMSO concentration: 0.1%) for 10 min and then treated with 2.5 μM Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (1 μl in methanol; final methanol concentration: 0.1%) for 15 min at 37°C. Monocytes (1.2 × 106 cells ml−1) in monocyte medium supplemented with FCS (5%, v/v) were pre‐incubated with test compounds (1 μl in DMSO; final DMSO concentration: 0.1%) for 10 min and then treated with 2 μg/ml LPS from E. coli 0127:B8 (Sigma‐Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany) for 24 h. Eicosanoid formation was stopped and eicosanoids extracted as described (Schaible et al., 2013a).

Reversed phase liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry

Eicosanoids (in 3 μl sample) were separated on an Acquity UPLC (Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography) BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm, Waters, Milford, MA) using an AcquityTM UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) as previously described (Koeberle et al., 2014; Schaible et al., 2013a). The chromatography system was coupled to a Quadrupole Ion Trap (QTRAP) 5500 Mass Spectrometer (AB Sciex, Darmstadt, Germany) equipped with an electrospray ionization source. Eicosanoids were quantified by multiple reaction monitoring in the negative using a previously reported method with a lower limit of detection of 150 to 600 pg ml−1 and linear quantification range up to 200 ng ml−1 (Koeberle et al., 2014). Automatic peak integration was performed with analyst 1.6 software (Sciex, Darmstadt, Germany) using IntelliQuan default settings. Data were normalized on the internal standard PGB1 and are given as relative intensities.

Docking studies

The chemical structures of CS and CA were built with maestro build panel (version 9.6) (Maestro, 2013) and processed with ligprep (version 2.8) (LigPrep, 2013), generating all the possible tautomers, protonation states at a pH of 7.4 ± 1.0, and finally minimized using optimized potentials for liquid simulations (OPLS, 2005) force field. The three‐dimensional structures of the protein targets mPGES‐1 (Li et al., 2014) and 5‐LO (Gilbert et al., 2011) (PDB code: 4BPM and 3O8Y respectively) were prepared with the Schrödinger Protein Preparation Wizard (Maestro, 2013). The water molecules were removed, all hydrogens were added and bond orders were assigned. Molecular docking studies of these two compounds, with mPGES‐1 as target, were performed using standard precision (SP) and extra precision mode (XP) mode (Glide version 6.1) (Friesner et al., 2004; Halgren et al., 2004; Friesner et al., 2006; Maestro, 2013). We chose coordinates and dimensions along x, y, z axes of the grid related to the site of presumed pharmacological interest (centered at 10.0557 (x), 16.6230 (y), 45.7128 (z), with inner box dimensions of 16 x 26 x 22 and outer box dimensions of 27 x 37 x 33).

Following the same procedure for 5‐LO, extra‐precision output results were analyzed, and best‐scoring poses were used as input to perform an induced‐fit docking for 5‐LO (Sherman et al., 2006a; Sherman et al., 2006b; Induced, 2013), choosing PHE177, TYR181, HIS367, LEU368, HIS372, LEU373, ILE406, LEU414, HIS550, ASN554, LEU607, ILE673 residues as flexible and the rest of the protein as rigid. We set a grid inner box size of 10 Å and grid outer box of 20 Å, saving 30 conformations as maximum number of binding modes. Illustrations of the 2D and 3D models were generated using Maestro (version 9.6) (Maestro, 2013).

Statistical analysis

The results obtained were expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by using one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's or Tukey's post hoc test. In some cases, one sample t‐test was used to evaluate significance against the hypothetical zero value. Statistical analysis was performed by using graphpad prism 4.0 software (San Diego, CA, USA). Data were considered statistically significant when a value of P < 0.05 was achieved. The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015).

Materials

CS and CA were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany). Test compounds were dissolved in DMSO, stored in the dark at −20°C, and freezing/thawing cycles were kept to a minimum. Carrageenan was obtained from Sigma‐Aldrich Co. (Milan, Italy). Unless otherwise stated, all the other reagents were from Carlo Erba Reagents (Milan, Italy).

Results

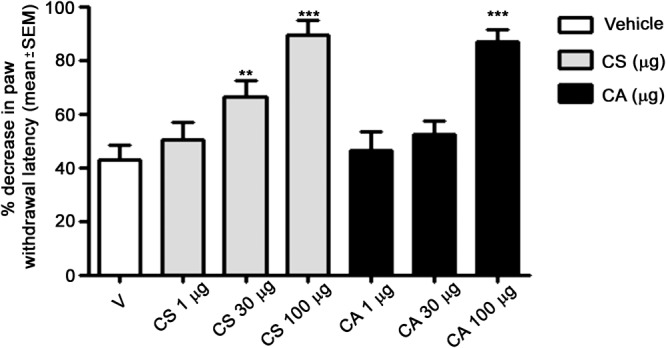

Effect of CS and CA on carrageenan‐induced hyperalgesia in mice

We determined the analgesic efficacy of CS and CA in carrageenan‐induced hyperalgesia, a well‐established murine pain model (Morris, 2003). As shown in Figure 2, both CS and CA displayed significant anti‐nociceptive effects 4 h after injection of carrageenan, when administered at a high dose (100 μg/paw). The anti‐hyperalgesic effect of CS was protracted even at a dose of 30 μg/paw (43.00±5.13 vs 66.33±5.89; P<0.01). No significant effects were observed for the diterpenoids at a dose of 1 μg/paw (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of CS and CA acid in the carrageenan‐induced hyperalgesia model. CS and CA were injected s.c. (1, 30 or 100 μg in 20 μL), 30 min before injection of 1% carrageenan (50 μL; s.c.) into the same hind paw of mice. Paw withdrawal was recorded 4 h after carrageenan administration. The results obtained are expressed as the mean ± SEM; n = 6. *P < 0.05; significantly different from vehicle control (V); one‐way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test.

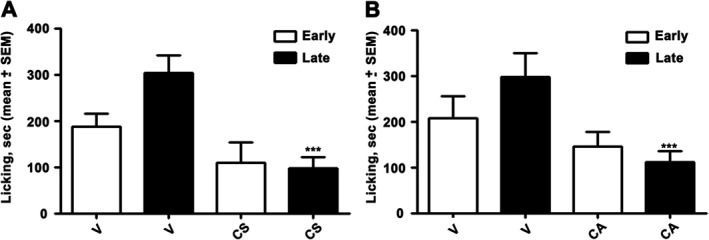

Effect of CS and CA on formalin‐induced pain in mice

As shown in Figure 3, the s.c. administration of CS and CA increased the nociceptive threshold in the formalin‐induced pain model in mice. Note that CS and CA significantly inhibited the pain response in the paw only in the late phase (302.6±39.50 vs 96.66±24.55; P<0.001 and 296.66±51.75 vs 112.00±23.25; P<0.001 for CS and CA respectively), when administered at the high dose (100 μg/paw).

Figure 3.

Effect of CS and CA in the formalin‐induced pain model. CS and CA were injected s.c. at a single dose (100 μg in 20 μL), 30 min before formalin injection (20 μL; s.c.). Early, licking activity recorded from 0 to 10 min after formalin administration; Late, licking activity recorded from 15 to 40 min after formalin administration. The results obtained are expressed as the mean ± SEM; n = 6. **P < 0.05; significantly different from vehicle control (V); one‐way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test.

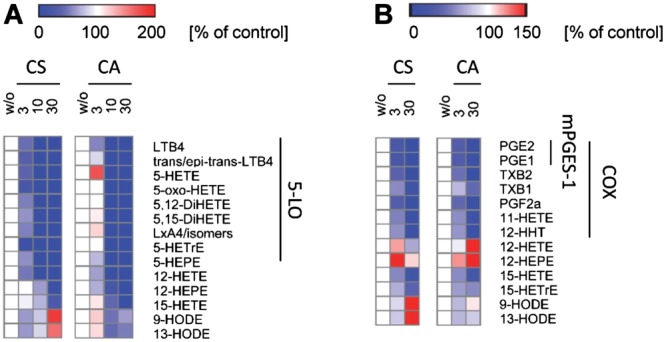

Effect of CS and CA on the eicosanoid profile of activated human neutrophils and monocytes

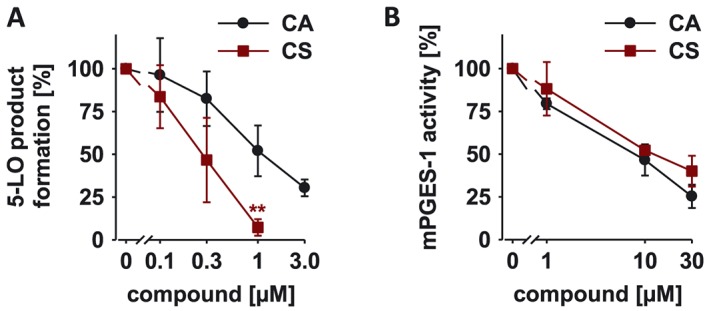

To shed light on the molecular mechanisms for the analgesic action of CS and CA in inflammatory pain, we investigated their effects on the pro‐inflammatory eicosanoid network. First, we confirmed that CS and CA potently inhibit 5‐LO (CS: IC50 = 0.3; CA: IC50 = 0.8 μM; Figure 4A) and mPGES‐1 (CS: IC50 = 10.9; CA: IC50 = 14.0 μM; Figure 4B), two key enzymes involved in inflammatory pain, in cell‐free assays, as previously described (Poeckel et al., 2008; Bauer et al., 2012).

Figure 4.

Effect of CS and CA on 5‐LOX (A) and mPGES‐1 activity (B). Residual activities (% of control) are shown as mean ± SEM of single determinations obtained in five (A) and three (B) independent experiments. A, *P < 0.05; significantly different from vehicle control; one way ANOVA with Tukey HSD post hoc tests.

Then, we analyzed the eicosanoid profile of activated immune cells using ultraperfomance liquid chromatography‐coupled with electrospray ionization (ESI) tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC‐MS/MS) analysis. Human freshly isolated neutrophils were pre‐treated with CS and CA (3 to 30 μM), and then stimulated with Ca2 +‐ionophore A23187 to induce eicosanoid formation. As expected, both CS and CA efficiently suppressed the generation of 5‐LO products derived from arachidonic acid (LTB4, LTB4 isomers, 5‐hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid (5‐HETE), 5‐oxo‐eicosatetraenoic acid (5‐oxo‐ETE), 5,12‐dihydroxy‐6,8,10,14‐eicosatetraenoic acid (5,12‐DiHETE), 5,15‐dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5,15‐DiHETE), and lipoxin (Lx)A4 and isomers), eicosatrienoic acid (5‐hydroxy‐eicosatrienoic acid (5‐HETrE)) and eicosapentaenoic acid (5‐hydroxy‐eicosapentaenoic acid (5‐HEPE) in neutrophils. In these assays, CS was more potent than CA, except for inhibition of LTB4 and 5‐HEPE formation (Figure 5A and Supporting Information Figure S1A). To access the effect of CS and CA on the prostanoid profile, we induced the expression of COX‐2 and mPGES‐1 and concomitant formation of prostanoids in human blood monocytes by LPS. CS and CA (3 to 30 μM) inhibited the formation of COX‐derived eicosanoids (PGE2, TxB2, PGF2α, 11‐hydroxy‐5,8,12,14‐eicosatetraenoic acid (11‐HETE), 12‐hydroxyheptadecatrenoic acid (12‐HHT), PGE1, and TxB1) with preference for mPGES‐1 products (PGE2 and PGE1; Figure 5B and Supporting Information Figure S1B). Differences in the potency between CS and CA were not observed, except for TxB1, whose formation was more potently inhibited by CS compared to CA (Figure 5B and Supporting Information Figure S1B).

Figure 5.

Effect of CS and CA on eicosanoid formation in activated human neutrophils (A) and monocytes (B). A, Neutrophils were pre‐incubated with vehicle (DMSO) or test compounds for 10 min before eicosanoid formation was initiated by A23187 (2.5 μM). B, Monocytes were pre‐incubated with vehicle (DMSO) or test items and then stimulated with LPS for 24 h. Heatmaps were prepared using Gene‐E 3.0 (Broad Institute) and show residual activities (percentage of vehicle control) as mean of single determinations obtained in three (A) and five (B) independent experiments. Red indicates a relative increase and blue a decrease of eicosanoid levels. 5‐LOX products: LTB4, trans/epi‐trans‐LTB4, 5‐oxo‐HETE, 5,12‐DiHETE, 5,15‐DiHETE, LXA4/isomers, 5‐HETrE, 5‐HEPE; 12/15‐LOX products: 12‐HETE, 12‐HEPE, 15‐HETE, 15‐HETrE, 5,12‐DiHETE, 5,15‐DiHETE, LXA4/isomers; COX products: PGE2, PGE1, TxB2, TxB1, PGF2α, 11‐HETE, 12‐HHT; mPGES‐1 products: PGE2, PGE1.

Besides 5‐LO product formation, CS and CA also suppressed the formation of distinct lipid mediators derived from 15‐LO and 12‐LO in activated immune cells (Figure 5 and Supporting Information Figure S1). Thus, CS inhibited 12‐hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12‐HETE) formation in neutrophils comparable to 5‐LO product formation while the production of 12‐hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12‐HEPE) and 15‐hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid (15‐HETE) was less potently suppressed (Figure 5A). In contrast, CA did not dissect between inhibition of 5‐LO and 12/15‐LO products in neutrophils. In LPS‐activated monocytes, both CS and CA rather induced 12‐HETE and 12‐HEPE formation, while 15‐HETE was equipotently inhibited compared to 5‐LO product formation, and 15‐hydroxyeicosatrienoic acid (15‐HETrE) formation was less potently suppressed (Figure 5B). Taken together, our results indicate that 5‐LO and mPGES‐1 are primary targets of CS and CA which shape the eicosanoid profile of activated innate immune cells.

Molecular docking studies of CS and CA

Our in silico studies are focused on mPGES‐1 and 5‐LO. Functionally, mPGES‐1 is mainly associated to COX‐2 and the induction of these two enzymes by pro‐inflammatory cytokines leads to an outpouring of PGE2 production by inflammatory cells.

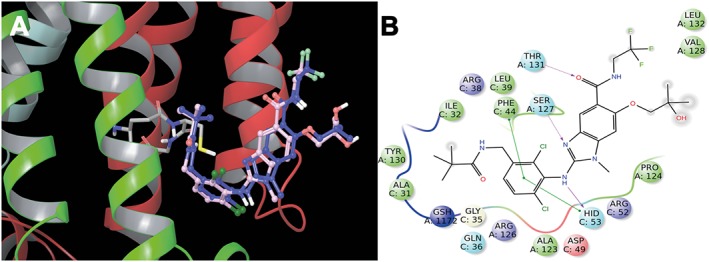

Interaction of CS and CA on mPGES‐1 binding sites

In order to propose a binding mode of CS and CA with the catalytic domain of mPGES‐1, we used herein for docking calculations the crystal structures of mPGES‐1 in complex with GSH and the inhibitor 2‐[[2,6‐bis(chloranyl)‐3‐[(2,2‐dimethylpropanoylamino)methyl]phenyl]amino]‐ 1‐methyl‐6‐(2‐methyl‐2‐oxidanyl‐propoxy)‐ N‐[2,2,2‐tris(fluoranyl)ethyl]benzimidazole‐ 5‐carboxamide, (shown as compound 3 in Figure 1); (Li et al., 2014) (PDB code: 4BPM). For our analysis, we referred to the binding mode of 3 which interacts with three equivalent active site cavities located at the membrane‐spanning region of each monomer interface. In more detail, we analyzed the three‐dimensional model (Figure 6) and observed an extended set of polar and hydrophobic interactions of 3 with the key residues responsible for the catalytic activity of the investigated protein (A:ARG126, A:SER127, and A:THR131). In particular, 3 adopts a peculiar shape in the binding site, and this is mainly due to a strong edge‐to‐face π−π interaction between its dichlorophenyl moiety and the phenyl group in the side chain of C:PHE44 and with C:HIS53 (Figure 6). The first step of our study is represented from the validation of the model, which was performed by molecular docking (Glide Software) (Friesner et al., 2004; Halgren et al., 2004; Friesner et al., 2006) of 3 with mPGES‐1 catalytic domain. As shown in Figure 6, our calculated model well reproduces the crystal binding mode of 3, where the majority of interactions are respected. After this step of validation, we performed molecular docking study of CS and CA with the enzyme.

Figure 6.

Superimposition of the inhibitor, compound 3, co‐crystallized (blue) and calculated (light pink) with mPGES‐1 (A). 2D panels of calculated interactions of compound 3 in mPGES‐1 binding site (B). Positive charged residues are coloured violet, negative charged residues are coloured red, polar residues are coloured light blue, and hydrophobic residues are coloured green. The π–π stacking interactions are indicated as green lines, and H‐bond (side chain) are reported as dotted pink arrows. Neutral histidine with hydrogen on the δ nitrogen is shown as HID, and neutral histidine with hydrogen on the ε nitrogen is shown as HIE.

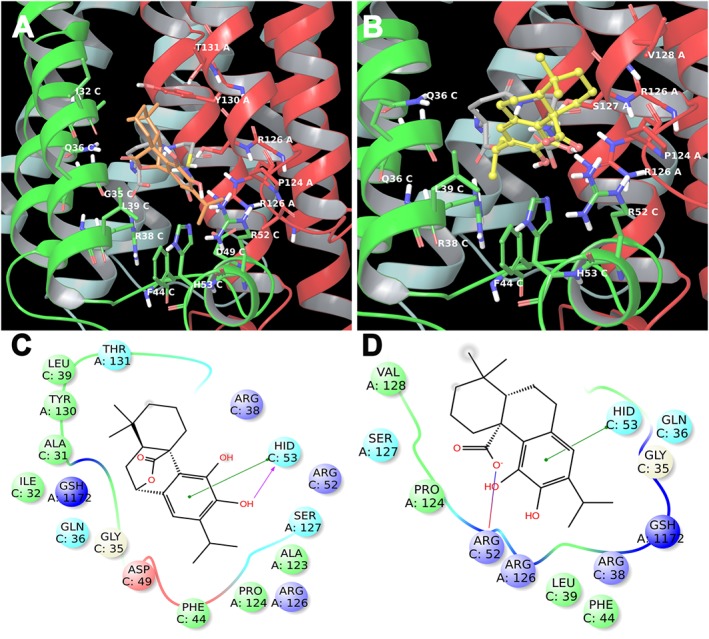

CS and CA are accommodated in the same pocket of 3 (Figure 7), establishing good interactions with receptor counterpart (Sjogren et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Luz et al., 2015). CS establishes fundamental hydrophobic, electrostatic and π‐π interactions namely with ARG38, PHE44, ARG52, HIS53 of chain C, and ARG126, PRO124, SER127, THR131 of chain A (Figure 7C), in analogy to the co‐crystallized ligand. Moreover, it makes interactions with GLY35, LEU39, ASP49 of the chain C, and ALA123 of the chain A (Figures 7A and C). On the other hand, CA shows the same pattern of key hydrophobic and π‐π interactions (see above), and hydrogen bond between the carboxyl group and ARG52 (Figures 7B and D).

Figure 7.

3D models of CS (A) (coloured by atom types: C orange, O red, polar H white) and CA (B) (coloured by atom types: C yellow, O red, polar H white) in the binding site of mPGES‐1 with GSH (coloured by atom types: C green, O red, polar H white). Residues in the active site are represented in tubes (coloured by atom types: C grey, N blue, O red, H white). 2D panels represent the interactions between CS (C), CA (D) and the residues of mPGES‐1 binding site. Positive charged residues are coloured violet, negative charged residues are coloured red, polar residues are coloured light blue, hydrophobic residues are coloured green. The π–π stacking interactions are indicated as green lines, and H‐bonds (side chain) are reported as dotted pink arrows. Neutral histidine with hydrogen on the δ nitrogen is shown as HID, and neutral histidine with hydrogen on the ε nitrogen is shown as HIE.

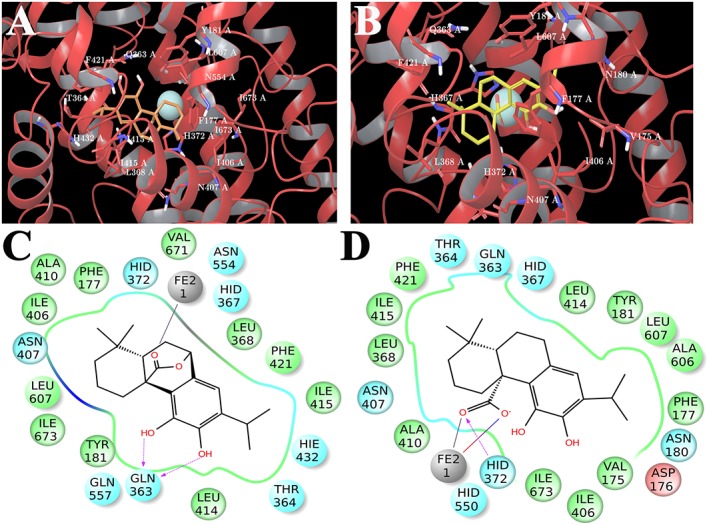

Interaction of CS and CA on 5‐LO binding sites

Regarding the 5‐LO enzyme, the induced fit docking approach was used to simulate and study the interactions of CS and CA with the residues that belong to the active site close to the catalytic iron of this enzyme (Gilbert et al., 2011). The analysis of the most representative docking poses of CS in the ligand binding site reveals a better accommodation with respect to CA as it establishes key interactions with PHE177, TYR181, LEU368, ILE406, ASN407, LEU414, LEU420, PHE421, HIS432, and LEU607 (Figure 8A). Moreover, it makes two hydrogen bonds with GLN363 and the carbonyl oxygen coordinates the metal (Figure 8C). CA shows a flipped binding mode with respect to CS maintaining the metal coordination, a hydrogen bond with HIS372, and the key interactions with PHE177, TYR181, LEU368, ILE406, ASN407, LEU414, PHE421, and LEU607, with the exception of contacts with LEU420 and HIS432 (Figure 8B and 8D).

Figure 8.

3D models of CS (A) (coloured by atom types: C orange, O red, polar H white) and CA (B) (coloured by atom types: C yellow, O red, polar H white) in the binding site of 5‐LOX. Residues in the active site are represented in tubes (coloured by atom types: C grey, N blue, O red, polar H white), and Fe ion is depicted as yellow cpk. 2D panels represent the interactions between CS (C), CA (D) and residues of the 5‐LOX binding site. Negative charged residues are coloured in red, polar residues are coloured in light blue, and hydrophobic residues are coloured in green. The H‐bond (side chain), metal coordination and salt bridge are indicated as dotted pink arrows, grey lines and blue/red lines respectively. Neutral histidine with hydrogen on the δ nitrogen is shown as HID, and neutral histidine with hydrogen on the ε nitrogen is shown as HIE.

Discussion

Pain is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage” (Loeser and Treede, 2008). Despite the rapid progresses in the development of several treatments of inflammatory pain, the efficacy and tolerability of conventional analgesics can be overshadowed by their unwanted side effects. The research on natural products, founded on their ethnopharmacological information, has provided significant contributions to drug improvement by the discovery of novel chemical structures and/or mechanism of actions in this respect (Rates, 2001; Maione et al., 2009; Maione et al., 2013; Maione et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2014; Maione et al., 2015a).

Along these lines, anti‐inflammatory and analgesic characteristics of some members of the diterpenoid family have been described that may essentially interfere with the multiple signaling pathways that are deregulated during inflammation and inflammatory pain syndromes. Among these diterpenoids, much attention has been recently pointed on CS and CA that have been identified in leave extracts of different Salvia spp. (Senorans et al., 2000; Ramirez et al., 2006; Amici et al., 2014). We started our study by assessing the effect of CS and CA on the modulation of peripheral inflammatory pain in a model of carrageenan‐induced hyperalgesia in mice. This test is commonly used as an experimental animal model of acute inflammation, essentially regulated by mediators such as histamine, serotonin, bradykinin (in the first 2 h), and successively by prostaglandins (starting at 3 to 4 h) mainly released from neutrophils and macrophages (Morris, 2003; Rauf et al., 2015). All these mediators detected at sites of inflammation orchestrate the inflammatory response by acting as vasodilators and hyperalgesic agents, and they simultaneously induce vascular permeability changes, erythema and oedema (Rackham and Ford‐Hutchinson, 1983). Moreover, their presence in the spinal cord and primary afferent neurons in pathological pain conditions has also been demonstrated (Noguchi and Okubo, 2011). Importantly, the results from the carrageenan‐induced paw hyperalgesia study demonstrate an anti‐hyperalgesic effect of both diterpenoids at 4 h, which is likely attributed to the inhibition of eicosanoid production.

In order to confirm the analgesic properties of CS and CA, the formalin‐induced pain test was employed. Formalin injection into the paw elicits a distinct biphasic nociceptive response. Centrally acting drugs such as opioids inhibit both early and late phases almost equally (Shibata et al., 1989) whereas nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids, which are primarily acting in the periphery, only inhibit the late phase. The inhibitory effect of the diterpenoids in the second phase suggests a potential anti‐inflammatory action (Muhammad et al., 2015). Thus, the two diterpenoids primarily relieve the second phase (inflammatory pain), which suggests an interference with eicosanoid biosynthesis.

CS and CA have been reported to interfere with key signal transduction pathways of inflammation and cancer but only few direct molecular targets have been identified besides 5‐LO and mPGES‐1. For example, CS inhibits the activation of nuclear factor κB (IC50 = 2.5‐10 μM; (Lo et al., 2002)), p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase (at 20 μM; (Lo et al., 2002)), extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (at 20 μM; (Lo et al., 2002)), β‐catenin (at 25 μM; (Moran et al., 2005)), and intracellular Ca2 + mobilization (IC50 ≈ 30 μM; (Poeckel et al., 2008)) and activates Nrf2 (EC50 = 1‐10 μM; (Martin et al., 2004)), phosphatidylinositol‐3‐kinase/Akt (at 10 μM; (Martin et al., 2004)), protein kinase C signaling (at 60 μM; (Subbaramaiah et al., 2002)) and peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ (EC50 ≈ 40 μM; (Rau et al., 2006)). Additionally, our in vitro results support the hypothesis that CS and CA could actually act by a mechanism related to the inhibition of PGE2 biosynthesis in accordance with inhibition of COX‐2 and leukocyte infiltration in inflamed tissues (Shibata et al., 1989; Mengoni et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2015). In fact, our present findings and previous data reveal that CS and CA interfere with key enzymes in eicosanoid formation, in particular with 5‐LO (Laughton et al., 1991; Poeckel et al., 2008), less prominent with mPGES‐1 (Bauer et al., 2012) and to minor degree with COX enzymes (Laughton et al., 1991). The superior potency of CS compared to CA seems to depend on differences in the 5‐LO binding affinity rather than in compound stability because CS is considered more stable than CA (Zhang et al., 2012). The impact of cellular metabolism on the concentration of CS and CA remains unclear. On this basis, we investigated how the multi‐target drugs CS and CA modulate the eicosanoid profile of activated human neutrophils and monocytes. Both compounds suppressed the formation of a wide range of 5‐LO‐ and COX‐derived lipid mediators. Excessive redirections as previously described for COX and mPGES‐1 inhibitors were not observed within the eicosanoid network (Koeberle and Werz, 2015). The superior selectivity for 5‐LO and mPGES‐1 compared to COX, 12‐ and 15‐LO rather precludes general effects of CS and CA on substrate supply or upstream signaling pathways such as LPS signal transduction. So far, our results strongly suggest that 5‐LO and mPGES‐1 and potentially 12‐ and 15‐LO represent relevant targets of CS and CA with impact on the eicosanoid network of primary innate immune cells. Moreover, in intact cells, the two diterpenoids seem to interfere to a considerable extent with COX activity, despite their failure to suppress isolated bovine COX‐1 and human recombinant COX‐2 in cell‐free assays (Bauer et al., 2012), either by direct enzyme inhibition in the cellular context or by diminished enzyme expression. In fact, both CS and CA have been reported to inhibit the activation of NF‐κB (Lo et al., 2002), (Yu et al., 2008), a critical transcription factor regulating the expression of inducible COX‐2 and mPGES‐1. Of interest, 5‐, 12‐ and/or 15‐LO activities are required for the biosynthesis of specialized pro‐resolving lipid mediators including resolvins, protectins and maresins (SPMs) (Serhan, 2014). The effect of CS and CA on the generation of SPMs remains elusive in light of the complex and partly opposing effects of CS and CA on the formation of 12‐ and 15‐LO products depending on lipid species, cell type and experimental condition. However, it is likely that also SPM biosynthesis is profoundly regulated by CS and CA with potential consequence for the resolution of inflammation. By molecular docking, we have characterized the interaction of CS and CA with mPGES‐1 and 5‐LO (Poeckel et al., 2008; Emami et al., 2013). Dual inhibitors that block both mPGES‐1 and 5‐LOX within arachidonic acid metabolic pathways are expected to possess clinical advantages over selective inhibitors of COX enzymes (Thoren et al., 2003; Samuelsson et al., 2007; Koeberle and Werz, 2014; Koeberle and Werz, 2015). For these reasons, the detailed analysis of the eicosanoid network together with contextual docking analysis on mPGES‐1 and 5‐LOX has represented a crucial step in the structural part of our study. Relating to mPGES‐1, we have analyzed the binding of CS and CA in the mPGES‐1 binding site in presence of the cofactor glutathione (GSH) (Sjogren et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Luz et al., 2015). An accurate analysis of the main interactions of compounds in the active site allows the rationalization of their activity (Sjogren et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Chini et al., 2015; Iranshahi et al., 2015; Luz et al., 2015; Terracciano et al., 2015). In particular, CS and CA are accommodated in the pocket situated in the region at the interface of the two mPGES‐1 subunits, establishing good interactions with the receptor counterpart. All the established interactions corroborate the comparable antagonist activity of both diterpenoids, in agreement with the experimental biological inhibition reported by Bauer et al. (2012), and their response to inflammatory pain reported above. Regarding 5‐LO, the induced fit docking approach was used to simulate and to study the interactions between 5‐LO and CS or CA with residues belonging to the active site close to the catalytic iron (Gilbert et al., 2011). These molecular results seem to be in accordance with the observed activity of the two diterpenoids on human recombinant enzyme and in activated human primary neutrophils.

Conclusions

In vivo evidences, molecular docking studies and eicosanoid profiling provide a mechanistic basis for the anti‐nociceptive effects of CS and CA associated with inflammatory pain. Our biological evaluation as well as the in silico data clearly show that CS and CA act on mPGES‐ 1 and 5‐LO leading to suppression of pro‐inflammatory eicosanoid formation. These conclusions render CS and CA interesting bioactive ingredients in Salvia spp. that are traditionally used as anti‐inflammatory remedies and paving the way for a rational use of Salvia spp. nutraceuticals.

Author contributions

F.M. and S.P. designed the study, performed part of experiments, interpreted the data and performed data analysis; A.B., V.C., M.G.C. and S.P. performed part of experiments; G.R., G.B., O.W., A.K. and N.M. interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript before submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Effect of CS and CA on eicosanoid formation in activated human neutrophils (A) and monocytes (B). A, Neutrophils were pre‐incubated with vehicle (DMSO) or test compounds for 10 min before eicosanoid formation was initiated by A23187 (2.5 μM). B, Monocytes were pre‐incubated with vehicle (DMSO) or test items and then stimulated with LPS for 24 h. Data are given as mean ± SEM. of single determinations obtained in three (A) and five (B) independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs.versus vehicle control; ANOVA + Tukey HSD post hoc tests.

Figure S2 3D models of CS (coloured by atom types: C orange, O red, polar H white) and CA (coloured by atom types: C yellow, O red, polar H white) in the binding site of 12‐LOX.

Figure S3 2D panels represent the interactions between CS (A), CA (B) and residues of the 12‐LO binding site. Negative charged residues are coloured in red, polar residues are coloured in light blue, hydrophobic residues are coloured in green. The H‐bond (side chain), metal coordination and salt bridge are indicated as dotted pink arrows, grey lines, and blue/red lines respectively.

Figure S4 3D models of CS (coloured by atom types: C orange, O red, polar H white) and CA (coloured by atom types: C yellow, O red, polar H white) in the binding site of 15‐LOX.

Figure S5 2D panels represent the interactions between CS (A), CA (B) and residues of the 15‐LOX binding site. Negative charged residues are coloured in red, polar residues are coloured in light blue, hydrophobic residues are coloured in green. The H‐bond (side chain), metal coordination and salt bridge are indicated as dotted pink arrows, grey lines, and blue/red lines respectively.

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the University of Salerno, and by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) Grant IG 2012 – IG_12777 and IG 2015 – IG_17440 – Bifulco Giuseppe.

Maione, F. , Cantone, V. , Pace, S. , Chini, M. G. , Bisio, A. , Romussi, G. , Pieretti, S. , Werz, O. , Koeberle, A. , Mascolo, N. , and Bifulco, G. (2017) Anti‐inflammatory and analgesic activity of carnosol and carnosic acid in vivo and in vitro and in silico analysis of their target interactions. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174: 1497–1508. doi: 10.1111/bph.13545.

Contributor Information

Andreas Koeberle, Email: andreas.koeberle@uni-jena.de.

Giuseppe Bifulco, Email: bifulco@unisa.it.

References

- Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 172: 6024–6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amici R, Bigogno C, Boggio R, Colombo A, Courtney SM, Dal Zuffo R et al. (2014). Chiral resolution and pharmacological characterization of the enantiomers of the Hsp90 inhibitor 2‐amino‐7‐[4‐fluoro‐2‐(3‐pyridyl)phenyl]‐4‐methyl‐7,8‐dihydro‐6H‐quinazolin‐5‐one oxime. ChemMedChem 9: 1574–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer J, Kuehnl S, Rollinger JM, Scherer O, Northoff H, Stuppner H et al. (2012). Carnosol and carnosic acids from Salvia officinalis inhibit microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase‐1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 342: 169–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruna S, Giovannini A, De Benedetti L, Principato MC, Ruffoni B (2006). Molecular analysis of Salvia spp. through RAPID markers. Acta Hort 723 (Proceedings of the Ist International Symposium on the Labiatae: Advances in Production, Biotechnology and Utilisation, 2006): 157–160.

- Chae IG, Yu MH, Im NK, Jung YT, Lee J, Chun KS et al. (2012). Effect of Rosemarinus officinalis L. on MMP‐9, MCP‐1 levels, and cell migration in RAW 264.7 and smooth muscle cells. J Med Food 15: 879–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chini MG, Ferroni C, Cantone V, Dambruoso P, Varchi G, Pepe A et al. (2015). Elucidating new structural features of the triazole scaffold for the development of mPGES‐1 inhibitors. Med Chem Commun 6: 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Colucci M, Maione F, Bonito MC, Piscopo A, Di Giannuario A, Pieretti S (2008). New insights of dimethyl sulphoxide effects (DMSO) on experimental in vivo models of nociception and inflammation. Pharmacol Res 57: 419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SP, Giembycz MA et al. (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C Di Lorenzo, M Dell'Agli, M Badea, L Dima, E Colombo, E Sangiovanni et al (2013). Plant food supplements with anti-inflammatory properties: A systematic review (II). Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 53: 507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emami F, Ali‐Beig H, Farahbakhsh S, Mojabi N, Rastegar‐Moghadam B, Arbabian S et al. (2013). Hydroalcoholic extract of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) and its constituent carnosol inhibit formalin‐induced pain and inflammation in mice. Pak J Biol Sci 16: 309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT et al. (2004). Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J Med Chem 47: 1739–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesner RA, Murphy RB, Repasky MP, Frye LL, Greenwood JR, Halgren TA et al. (2006). Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein‐ligand complexes. J Med Chem 49: 6177–6196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giamperi L, Bucchini A, Bisio A, Giacomelli E, Romussi G, Ricci D (2012). Total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of Salvia spp. exudates. Nat Prod Commun 7: 201–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert NC, Bartlett SG, Waight MT, Neau DB, Boeglin WE, Brash AR et al. (2011). The structure of human 5‐lipoxygenase. Science 331: 217–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren TA, Murphy RB, Friesner RA, Beard HS, Frye LL, Pollard WT et al. (2004). Glide: A new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 2. Enrichment factors in database screening. J Med Chem 47: 1750–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Induced Fit Docking, protocol 2013‐3, Glide version 6.1, Prime version 3.4. (2013). Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Iranshahi M, Chini MG, Masullo M, Sahebkar A, Javidnia A, Yazdi MC et al. (2015). Can small chemical modifications of natural pan‐inhibitors modulate the biological selectivity? The case of curcumin prenylated derivatives acting as HDAC or mPGES‐1 inhibitors. J Nat Prod 78: 2867–2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JJ (2011). Carnosol: A promising anti‐cancer and anti‐inflammatory agent. Cancer Lett 305: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG, Group NCRRGW (2010). Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeberle A, Siemoneit U, Buehring U, Northoff H, Laufer S, Albrecht W et al. (2008). Licofelone suppresses prostaglandin E(2) formation by interference with the inducible microsomal prostaglandin E(2) synthase‐1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 326: 975–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeberle A, Northoff H, Werz O (2009). Identification of 5‐lipoxygenase and microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase‐1 as functional targets of the anti‐inflammatory and anti‐carcinogenic garcinol. Biochem Pharmacol 77: 1513–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeberle A, Munoz E, Appendino GB, Minassi A, Pace S, Rossi A et al. (2014). SAR studies on curcumin's pro‐inflammatory targets: discovery of prenylated pyrazolocurcuminoids as potent and selective novel inhibitors of 5‐lipoxygenase. J Med Chem 57: 5638–5648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeberle A, Werz O (2014). Multi‐target approach for natural products in inflammation. Drug Discov Today 19: 1871–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeberle A, Werz O (2015). Perspective of microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase‐1 as drug target in inflammation‐related disorders. Biochem Pharmacol 98: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu JK, Shin YK, Kim SH, Surh YJ (2006). Resveratrol inhibits phorbol ester‐induced expression of COX‐2 and activation of NF‐kappa B in mouse skin by blocking I kappa B kinase activity. Carcinogenesis 27: 1465–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughton MJ, Evans PJ, Moroney MA, Hoult JR, Halliwell B (1991). Inhibition of mammalian 5‐lipoxygenase and cyclo‐oxygenase by flavonoids and phenolic dietary additives. Relationship to antioxidant activity and to iron ion‐reducing ability. Biochem Pharmacol 42: 1673–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Howe N, Dukkipati A, Shah STA, Bax BD, Edge C et al. (2014). Crystallizing membrane proteins in the lipidic mesophase. Experience with human prostaglandin E2 synthase 1 and an evolving strategy. Cryst Growth Des 14: 2034–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LigPrep, version 2.8. (2013). Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Lo AH, Liang YC, Lin‐Shiau SY, Ho CT, Lin JK (2002). Carnosol, an antioxidant in rosemary, suppresses inducible nitric oxide synthase through down‐regulating nuclear factor‐kappaB in mouse macrophages. Carcinogenesis 23: 983–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeser JD, Treede RD (2008). The Kyoto protocol of IASP Basic Pain Terminology. Pain 137: 473–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luz JG, Antonysamy S, Kuklish SL, Condon B, Lee MR, Allison D et al. (2015). Crystal structures of mpges‐1 inhibitor complexes form a basis for the rational design of potent analgesic and anti‐inflammatory therapeutics. J Med Chem 58: 4727–4737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestro, version 9.6. (2013). Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Maione F, Bonito MC, Colucci M, Cozzolino V, Bisio A, Romussi G et al. (2009). First evidence for an anxiolytic effect of a diterpenoid from Salvia cinnabarina. Nat Prod Commun 4: 469–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maione F, Cicala C, Musciacco G, De Feo V, Amat AG, Ialenti A et al. (2013). Phenols, alkaloids and terpenes from medicinal plants with antihypertensive and vasorelaxant activities. A review of natural products as leads to potential therapeutic agents. Nat Prod Commun 8: 539–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maione F, De Feo V, Caiazzo E, De Martino L, Cicala C, Mascolo N (2014). Tanshinone IIA, a major component of Salvia milthorriza Bunge, inhibits platelet activation via Erk‐2 signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 155: 1236–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maione F, Cantone V, Chini MG, De Feo V, Mascolo N, Bifulco G (2015a). Molecular mechanism of tanshinone IIA and cryptotanshinone in platelet anti‐aggregating effects: an integrated study of pharmacology and computational analysis. Fitoterapia 100: 174–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maione F, Russo R, Khan H, Mascolo N (2015b). Medicinal plants with anti‐inflammatory activities. Nat Prod Res : 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D, Rojo AI, Salinas M, Diaz R, Gallardo G, Alam J et al. (2004). Regulation of heme oxygenase‐1 expression through the phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase/Akt pathway and the Nrf2 transcription factor in response to the antioxidant phytochemical carnosol. J Biol Chem 279: 8919–8929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Lilley E (2015). Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): new requirements for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3189–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengoni ES, Vichera G, Rigano LA, Rodriguez‐Puebla ML, Galliano SR, Cafferata EE et al. (2011). Suppression of COX‐2, IL‐1 beta and TNF‐alpha expression and leukocyte infiltration in inflamed skin by bioactive compounds from Rosmarinus officinalis L. Fitoterapia 82: 414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirjalili MH, Salehi P, Sonboli A, Vala MM (2006). Essential oil variation of Salvia officinalis aerial parts during its phenological cycle. Chem Nat Comp 42: 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- T Miyata (2007). Pharmacological basis of traditional medicines and health supplements as curatives. J Pharmacol Sci 103: 127-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran AE, Carothers AM, Weyant MJ, Redston M, Bertagnolli MM (2005). Carnosol inhibits beta‐catenin tyrosine phosphorylation and prevents adenoma formation in the C57BL/6J/Min/+ (Min/+) mouse. Cancer Res 65: 1097–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CJ (2003). Carrageenan‐induced paw edema in the rat and mouse. Methods Mol Biol 225: 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad N, Shrestha RL, Adhikari A, Wadood A, Khan H, Khan AZ et al. (2015). First evidence of the analgesic activity of govaniadine, an alkaloid isolated from Corydalis govaniana Wall. Nat Prod Res 29: 430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi K, Okubo M (2011). Leukotrienes in nociceptive pathway and neuropathic/inflammatory pain. Biol Pharm Bull 34: 1163–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeckel D, Greiner C, Verhoff M, Rau O, Tausch L, Hornig C et al. (2008). Carnosic acid and carnosol potently inhibit human 5‐lipoxygenase and suppress pro‐inflammatory responses of stimulated human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Biochem Pharmacol 76: 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raal A, Orav A, Arak E (2007). Composition of the essential oil of Salvia officinalis L. from various European countries. Nat Prod Res 21: 406–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rackham A, Ford‐Hutchinson AW (1983). Inflammation and pain sensitivity: effects of leukotrienes D4, B4 and prostaglandin E1 in the rat paw. Prostaglandins 25: 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez P, Garcia‐Risco MR, Santoyo S, Senorans FJ, Ibanez E, Reglero G (2006). Isolation of functional ingredients from rosemary by preparative‐supercritical fluid chromatography (Prep‐SFC). J Pharm Biomed Anal 41: 1606–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall LO, Selitto JJ (1957). A method for measurement of analgesic activity on inflamed tissue. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther 111: 409–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rates SMK (2001). Plants as source of drugs. Toxicon 39: 603–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau O, Wurglics M, Paulke A, Zitzkowski J, Meindl N, Bock A et al. (2006). Carnosic acid and carnosol, phenolic diterpene compounds of the labiate herbs rosemary and sage, are activators of the human peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma. Planta Med 72: 881–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauf A, Khan R, Raza M, Khan H, Pervez S, De Feo V et al. (2015). Suppression of inflammatory response by chrysin, a flavone isolated from Potentilla evestita Th. Wolf In silico predictive study on its mechanistic effect. Fitoterapia 103: 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues MRA, Kanazawa LKS, das Neves TLM, da Silva CF, Horst H, Pizzolatti MG et al. (2012). Antinociceptive and anti‐inflammatory potential of extract and isolated compounds from the leaves of Salvia officinalis in mice. J Ethnopharmacol 139: 519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen A, Lehtonen M, Suuronen T, Kaarniranta K, Huuskonen J (2008). Terpenoids: natural inhibitors of NF‐kappaB signaling with anti‐inflammatory and anticancer potential. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 2979–2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson B, Morgenstern R, Jakobsson PJ (2007). Membrane prostaglandin E synthase‐1: a novel therapeutic target. Pharmacol Rev 59: 207–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible AM, Koeberle A, Northoff H, Lawrenz B, Weinigel C, Barz D et al. (2013a). High capacity for leukotriene biosynthesis in peripheral blood during pregnancy. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 89: 245–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible AM, Traber H, Temml V, Noha SM, Filosa R, Peduto A et al. (2013b). Potent inhibition of human 5‐lipoxygenase and microsomal prostaglandin E(2) synthase‐1 by the anti‐carcinogenic and anti‐inflammatory agent embelin. Biochem Pharmacol 86: 476–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senorans FJ, Ibanez E, Cavero S, Tabera J, Reglero G (2000). Liquid chromatographic‐mass spectrometric analysis of supercritical‐fluid extracts of rosemary plants. J Chromatogr 870: 491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN (2014). Pro‐resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature 510: 92–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman W, Beard HS, Farid R (2006a). Use of an induced fit receptor structure in virtual screening. Chem Biol Drug Des 67: 83–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman W, Day T, Jacobson MP, Friesner RA, Farid R (2006b). Novel procedure for modeling ligand/receptor induced fit effects. J Med Chem 49: 534–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Ohkubo T, Takahashi H, Inoki R (1989). Modified formalin test ‐ characteristic biphasic pain response. Pain 38: 347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjogren T, Nord J, Ek M, Johansson P, Liu G, Geschwindner S (2013). Crystal structure of microsomal prostaglandin E‐2 synthase provides insight into diversity in the MAPEG superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 3806–3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SPH et al. (2016). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucleic Acids Res 44 (Database Issue): D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaramaiah K, Cole PA, Dannenberg AJ (2002). Retinoids and carnosol suppress cyclooxygenase‐2 transcription by CREB‐binding protein/p300‐dependent and ‐independent mechanisms. Cancer Res 62: 2522–2530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano S, Lauro G, Strocchia M, Fischer K, Werz O, Riccio R et al. (2015). Structural Insights for the optimization of dihydropyrimidin‐2(1H)‐one based mPGES‐1 inhibitors. ACS Med Chem Lett 6: 187–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoren S, Weinander R, Saha S, Jegerschold C, Pettersson PL, Samuelsson B et al. (2003). Human microsomal prostaglandin E synthase‐1: purification, functional characterization, and projection structure determination. J Biol Chem 278: 22199–22209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa C, Trucchi B, Bertoli A, Pistelli L, Parodi A, Bassi AM et al. (2009). Int J Cosmet Sci 31: 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu YM, Lin HC, Chang WC (2008). Carnosic acid prevents the migration of human aortic smooth muscle cells by inhibiting the activation and expression of matrix metalloproteinase‐9. Br J Nutr 100: 731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Smuts JP, Dodbiba E, Rangarajan R, Lang JC, Armstrong DW (2012). Degradation study of carnosic acid, carnosol, rosmarinic acid, and rosemary extract (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) assessed using HPLC. J Agric Food Chem 60: 9305–9314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Garg G, Zhao J, Moroni E, Girgis A, Franco LS et al. (2015). Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of biphenylamide derivatives as Hsp90 C‐terminal inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem 89: 442–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Moroni E, Colombo G, Blagg BS (2014). Identification of a new scaffold for hsp90 C‐terminal inhibition. ACS Meed Chem Lett 5: 84–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Effect of CS and CA on eicosanoid formation in activated human neutrophils (A) and monocytes (B). A, Neutrophils were pre‐incubated with vehicle (DMSO) or test compounds for 10 min before eicosanoid formation was initiated by A23187 (2.5 μM). B, Monocytes were pre‐incubated with vehicle (DMSO) or test items and then stimulated with LPS for 24 h. Data are given as mean ± SEM. of single determinations obtained in three (A) and five (B) independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs.versus vehicle control; ANOVA + Tukey HSD post hoc tests.

Figure S2 3D models of CS (coloured by atom types: C orange, O red, polar H white) and CA (coloured by atom types: C yellow, O red, polar H white) in the binding site of 12‐LOX.

Figure S3 2D panels represent the interactions between CS (A), CA (B) and residues of the 12‐LO binding site. Negative charged residues are coloured in red, polar residues are coloured in light blue, hydrophobic residues are coloured in green. The H‐bond (side chain), metal coordination and salt bridge are indicated as dotted pink arrows, grey lines, and blue/red lines respectively.

Figure S4 3D models of CS (coloured by atom types: C orange, O red, polar H white) and CA (coloured by atom types: C yellow, O red, polar H white) in the binding site of 15‐LOX.

Figure S5 2D panels represent the interactions between CS (A), CA (B) and residues of the 15‐LOX binding site. Negative charged residues are coloured in red, polar residues are coloured in light blue, hydrophobic residues are coloured in green. The H‐bond (side chain), metal coordination and salt bridge are indicated as dotted pink arrows, grey lines, and blue/red lines respectively.

Supporting info item