Abstract

Increasing immigration and school ethnic segregation have raised concerns about the social integration of minority students. We examined the role of immigrant status in social exclusion and the moderating effect of classroom immigrant density among Swedish 14–15-year olds (n = 4795, 51 % females), extending conventional models of exclusion by studying multiple outcomes: victimization, isolation, and rejection. Students with immigrant backgrounds were rejected more than majority youth and first generation non-European immigrants were more isolated. Immigrants generally experienced more social exclusion in immigrant sparse than immigrant dense classrooms, and victimization increased with higher immigrant density for majority youth. The findings demonstrate that, in addition to victimization, subtle forms of exclusion may impede the social integration of immigrant youth but that time in the host country alleviates some risks for exclusion.

Keywords: Social exclusion, Victimization, School segregation, Ethnic composition, Immigrant, Adolescence

Introduction

Recent increases in immigration have made efforts to support the social integration of immigrant youth an important priority for schools in many European countries. This is vital for reducing prejudice, for protecting minority groups from social marginalization and for promoting social cohesion (cf., Pettigrew and Tropp 2008). Adolescents spend the majority of their time at school, and establishing positive peer relations in this context forms a key aspect of integration. During adolescence, a particularly high priority is given to acceptance among peers and positive relations provide social support and also promote youth’s self-worth and sense of identity (Berndt 1999; LaFontana and Cillessen 2010). Thus, social exclusion during this period is concerning because it coincides with an increased developmental need for peer affiliation, and marginalization can seriously undermine adolescents’ mental well-being, school adjustment, and even subsequent health (McCormick et al. 2011; Östberg and Modin 2008; Wolke et al. 2013). For immigrant youth, peers have additional benefits of promoting engagement in the host culture and opportunities to develop cultural and language skills (Berry et al. 2006), and poor relations present particularly important challenges for well-being (Hjern et al. 2013).

This study contributes to a comprehensive understanding of the role that immigrant background plays in social exclusion among peers during adolescence. According to “social misfit” theory (Wright et al. 1986), individuals tend to be rejected when they differ to others according to one or several characteristics, and immigrant background can be such a characteristic (Jackson et al. 2006; Vervoot et al. 2010). The “power imbalance” theory also argues that vulnerability to exclusion is greater in contexts where one’s ethnic group comprises a situational minority (Graham 2006), which occurs on a regular basis in ethnically segregated schools. Therefore, classroom immigrant density may play an important role in the social exclusion of youth.

Previous research on social exclusion in the school context has identified bully victimization as an area of concern but largely overlooked possible harm through other important, but often more subtle or even unintentional social dynamics. Motivated by the centrality of peer social acceptance to adolescent well-being (Brown 2004), we extend the understanding of social exclusion and ethnicity by examining isolation and rejection in addition to victimization. Drawing on a recent school sample of Swedish adolescents (n = 4795), we ask if immigrant status functions as a signal of “difference” in predicting different aspects of social exclusion and if classroom immigrant density moderates these relationships.

Ethnicity, Classroom Ethnic Composition, and Social Exclusion

Belonging to an ethnic minority has been identified as a risk factor for exclusion among peers. Social identity theory proposes that individuals desire to identify with and belong to social groups seen as superior to others (Tajfel 1982). This tendency results in preferences that favor or promote the in-group’s status, often at the expense of other groups. Within the school context, youth strive for a high position within the social hierarchy and may (intentionally or unintentionally) distance themselves from those who are perceived as belonging to a lower status group, such as immigrants (Bellmore et al. 2012). However, empirical findings on differences in social exclusion between majority and immigrant youth have been mixed. Some studies find that ethnic minorities report greater experiences of being bullied than majority youth (Hjern et al. 2013; Sulkowski et al. 2014) and are preferred or liked less than majority youth (Motti-Stefanidi et al. 2008; Strohmeier and Spiel, 2003; Strohmeier et al. 2011; Wilson and Rodkin 2011). However, other studies find no such differences (Fandrem et al. 2009; McKenney et al. 2006), or even find that minority groups are less likely than the majority to be identified as victims (Hanish and Guerra 2000; Strohmeier et al. 2008).

Social ecological perspectives provide a more nuanced understanding of social exclusion by considering how individual characteristics may interact with the social context surrounding peer relations (Hong and Espelage 2012). Similarity to others increases one’s likelihood of social acceptance, and friendships are typically formed on the basis of homophily in demographic characteristics and interests (e.g., McPherson et al. 2001). Conversely, youth tend to be rejected when they are noticeably different from the others (Mendez et al. 2012; Nadeem and Graham 2005; Qin et al. 2008; Strohmeier et al. 2011). The social misfit hypothesis proposes that children who deviate from the group norm and are different in some discernible way, such as behaviors or appearance, are often targeted for victimization (Boivin et al. 1995; Wright et al. 1986). Immigrant or ethnic minority students often deviate in such ways and thus may be perceived as not “fitting in”, particularly in school classes with only a small proportion of immigrant classmates.

The power imbalance theory (see Graham 2006; Juvonen et al. 2006) argues that individuals are more likely to be victimized in circumstances where their ethnic group is relatively small because they hold less social power. Although ethnicity in itself may represent power, ethnically segregated classes pose risks for youth whose group is poorly represented. An immigrant dense class thus, may increase the balance of power for minorities whose ethnic group may otherwise hold a low status position in society (Graham 2006; Juvonen et al. 2006). Although the misfit and power imbalance theories emphasize different mechanisms, both processes are likely involved in the social dynamics leading to marginalization. In combination, they suggest that both immigrant and majority youth may be at increased risk of exclusion in classrooms where they comprise the minority because they are less similar to classmates and hold less social power in such contexts. While school segregation poses risks, in some circumstances it may also protect youth, particularly immigrant youth, from social exclusion (Thijs et al. 2014; Vitoroulis et al. 2015) due to a greater likelihood of fitting in and shifting of power balances.

Studies from several Northern American and European countries have indeed found that immigrants, particularly those with non-European backgrounds, experience less victimization in schools with higher proportions of immigrants (Agirdag et al. 2011; Hjern et al. 2013; Vitoroulis et al. 2015; Walsh et al. 2016). These studies also found no effect of immigrant density on ethnic majority children’s likelihood of victimization. Thus, majority youth’s social standing may be less sensitive to variations in classroom ethnic composition. Consistent with this, there is some evidence that minority youth tend to show weaker same-ethnic preferences than majority youth (Griffiths and Nesdale 2006; Vervoort et al. 2010). However, other studies have found that majority youth experience greater victimization in contexts with higher immigrant density (Verkuyten and Thijs 2002), indicating that class ethnic composition is also relevant to majority youth’s social vulnerability.

Broadening the Conceptualization of Social Exclusion

Research on social exclusion among peers and immigrant or ethnic background has largely focused on bully victimization, an extreme form of explicit social exclusion. However, there are arguably milder forms of exclusion based on more subtle social processes that are also highly relevant for social integration and cohesion. The social belonging literature argues that social connectedness is a fundamental need (Baumeister and Leary 1995; Ryan and Deci 2000) and schools represent a key social environment for adolescents. Given the importance that social affiliation with peers plays in adolescent well-being (Brown 2004), alternative aspects of social exclusion among classmates should also be considered. In line with theories of homophily (McPherson et al. 2001) and social group identification (Tajfel 1982), youth tend to interact with similar others and favor in-group than out-group ethnic peers (Baerveldt et al. 2007; Levy and Killen 2010), even in casual interactions (Fortuin et al. 2014). Although explicit ethnic bias decreases during childhood, implicit biases continue throughout adolescence (Dunham et al. 2006) and may be reflected in these preferences. Furthermore, peer relations are also formed based on a range of interests and values that often unintentionally overlap with ethnicity (Stark and Flache 2012).

These seemingly innocent social preferences can have negative secondary effects of enhancing segregation and social marginalization by inadvertently ostracizing individuals with certain characteristics. Thus, we argue that a broader perspective of social exclusion is needed that considers milder or even implicit forms of marginalization. Being rejected (disliked or not preferred) or ignored by peers are notable aspects of such forms of exclusion. Low peer status and friendlessness pose risks for youth’s positive adjustment (Almquist 2011) and increase the likelihood of future victimization (Strohmeier et al. 2011). These dimensions of social exclusion may also promote social dynamics in the broader community that lead to an overall lack of inter-ethnic contact and social integration. By focusing on rejection and isolation, in addition to bullying, we intend to broaden the understanding of social exclusion among immigrant youth. With multiple measures, we can also study ethnic differences across multiple facets of social exclusion, as cumulative disadvantage would present a serious challenge for social integration.

The Swedish Context

In recent decades, Sweden has transformed from relatively homogenous into a multicultural society. The growth in immigration is reflected in the student population (Böhlmark et al. 2016). For example, the proportion of children with an immigrant background increased from 14 to 20 % between only 2000 and 2011 (Holmlund et al. 2014; Statistics Sweden 2013). In the wake of this development, and like several other European Union (EU) countries, there is substantial ethnic residential and school segregation as well as higher rates of poverty among immigrants, especially those from non-Western countries (Eurostat 2011; Mood and Jonsson 2016). The Swedish context is noteworthy because unlike many other countries, most immigrants come for humanitarian reasons or family reunification, and from a diverse range of countries. A large proportion of immigrants are refugees–particularly those from Middle Eastern, African, and Asian countries. Other immigrants, mostly from Nordic or EU countries move due to economic opportunities. Differences in cultural, economic, educational, and religious characteristics of these Middle Eastern, African, and Asian regions are typically greater than of other European or Western regions, and these individuals are considered to represent a “visual” immigrant status in Swedish society (Hjern et al. 2013). In recent times, the social climate in Sweden has polarized with a vocal criticism in political and social discourse regarding the integration of immigrant youth, mostly targeted at those from more distant regions. This demographic change in the student population presents challenges in promoting social integration in schools.

Most theories of immigrant integration propose that exposure to the host country culture and language facilitates integration through acculturation (Berry 1997)—immigrants gradually become more similar to the majority population with greater time spent in the host country (Alba and Nee 2009). This is often operationalized by distinguishing between “generations” of immigrants. First generation immigrants have moved to the host country and second generation immigrants were born in the host country but have foreign-born parents. It is particularly important to distinguish between these groups because many first generation immigrants not only come new to the school and community, but also typically without previous social networks or local language skills (almost no immigrants speak Swedish upon arrival). The second generation generally has an advantage in terms of language proficiency, cultural familiarity, and socioeconomic stability. Although studies on peer relations often fail to recognize generational differences, analyzing these groups together overlooks potential heterogeneity in important acculturation processes. To address this limitation, we will test both first and second immigrant generation.

Background Factors to Consider When Examining Immigrant Status and Social Exclusion

It is important to control for potentially confounding factors when examining peer relations and immigrant status. Poorer peer relations may be shaped by a range of characteristics that often coincide with ethnicity (Stark and Flache 2012), such as lower family socioeconomic status (Hjalmarsson and Mood 2015; Wolke et al. 2013). Parent separation/divorce is also a risk for peer rejection but is observed less often in some immigrant groups (UNICEF 2009). We will, therefore, control for socioeconomic background and family structure. In addition, class size will be controlled for because the number of classmates provides a structural condition that can influence the probability of social contact, victimization, and friendship formation (Verkuyten and Thijs 2002).

The Current Study

The main aim of this study is to examine the role of immigrant status in different aspects of social exclusion and the moderating role of classroom ethnic composition. We extend previous research on social exclusion during adolescence in three ways. Firstly, three aspects of social exclusion at school will be examined: peer victimization (from self-reports), social isolation, and rejection (both based on peer-reports). Secondly, immigrant background will be examined according to generation of migration as well as region of origin. Thirdly, key background factors will be controlled for to reduce potential confounding in associations between immigrant status and social exclusion.

If immigrant background generally functions as a characteristic signaling “difference”, then immigrant youth are expected to be more socially excluded than majority youth (Hypothesis 1). Focusing on the classroom context, in line with both the social misfit and power imbalance theories, immigrant youth are expected to experience greater social exclusion in immigrants parse classrooms than immigrant dense classrooms (Hypothesis 2). Conversely, if majority youth’s social status is also contextually sensitive, then majority youth are expected to experience greater social exclusion in more immigrant dense classrooms (Hypothesis 3). According to acculturation theory, second generation immigrants will be less different to majority youth and hold greater social power than first generation immigrants, and are, therefore, expected to be less socially excluded (Hypothesis 4). If a key mechanism for social exclusion is being a “visible” minority, then youth with a non-European (“non-white”) background will be more likely to experience social exclusion than those with a European (“white”) background (Hypothesis 5).

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Data is drawn from the Youth in Europe Study (YES!), which is part of a larger international study, Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Four European Countries (CILS4EU), funded by New Opportunities for Research Funding Agency Cooperation in Europe (NORFACE) (Kalter et al. 2013). The project is designed with a focus on the structural and social aspects of young people’s living conditions that are important to integration and well-being. This study draws on Swedish data from the first wave of data collection (winter 2010 and spring 2011) when respondents (n = 5,025, 49 % males and 51 % females) were in the eighth grade and ~14 to 15 years of age (mean = 14.69, S.D. = 38). In the Swedish school system, eighth grade students have normally been in the same class for ~2–4 years (depending on the school) and attend nearly all lessons together. Thus, the social dynamics in these school classes were established and represent an important social arena for the students.

Statistics Sweden (the Swedish government statistics agency) collected the data using a two-step stratified cluster sampling approach. Schools across Sweden were randomly selected within four strata defined by the proportion of immigrant youth, over-sampling immigrant dense schools. Within each school two randomly drawn classes, and all pupils in them, were invited to participate. Over 90 % of schools and 86 % of students participated (non-response was mostly due to the absence and did not vary across minority–majority groups). Official survey weights were provided that adjust for sample design and non-response to ensure the sample is representative of the Swedish population of eight-graders in the school year 2010/11.

Participants completed a set of self-report questionnaires and tests, as well as sociometric nominations. Questionnaires took ~80 min to complete during lesson time, and students were informed that participation was voluntary and that their responses were anonymous. Parents also completed postal questionnaires. The current study used parental reports to complement student information on immigrant status and family structure. Survey data is available at www.gesis.org (ZA5353 data file). Information on family socioeconomic status and age of immigration was also drawn from tax, immigration, and education population registers held by Statistics Sweden.

Measures

Social Exclusion Outcomes

Rejection

Rejection reflected classmates’ preferences regarding which peers were perceived as socially undesirable within the classroom context. It was based on the following sociometric item: “Who do you not want to sit next to?” Students could nominate up to five classmates from a roster that listed the names of all students in the class. Over 60 % of participants received at least one nomination. Those receiving three or more nominations from their classmates were categorized as rejected. Sensitivity analyses using alternative cut-offs came to substantively similar findings and are described in the results section.

Isolation

Isolation represented youth who were ignored or neglected by their classmates. Students were asked “Who is your very best friend in class?” and “Who are your best friends in class?” Participants could nominate one classmate for the first item and up to five for the second, in no particular order from the roster of names. Received friendship nominations were summed and those receiving no friendship nominations were categorized as isolated.

Victimization

Peer victimization was assessed by three items asking participants how often in the past month they had been bullied, teased, or been made to feel scared of other students. Respondents reporting any of these experiences at least once a week, or all three experiences monthly were categorized as having been victimized. This is consistent with definitions of victimization as frequent and ongoing events (Olweus 1993).

Key Predictors

Immigrant Status

Data on immigrant status came from student-reports, complemented with parent-reports or population register information in the case of student non-response. Participants were categorized as majority if they were the biological or adoptive child of at least one Swedish-born parent. This is consistent with the official definition used by the Swedish statistics bureau (Statistics Sweden). First generation immigrants included youth born abroad to foreign-born parents and second generation immigrants included those born in Sweden to foreign-born parents. Region of origin was categorized according the parents’ country of birth prioritizing the mother’s country of birth if parents came from different countries. The immigrant sample included 1477 (31 %) individuals from the Middle East (13 %), Southern Europe (6 %), Africa (4 %), Asia (3 %), Eastern Europe (2 %), Latin America (1 %), and Western Europe or other Western countries (1 %). Due to the heterogeneity and low numbers in origin subgroups, we attempted to identify groups who differ to the majority Swedish population on several characteristics. Youth whose parents came from European or other Western countries (within Europe and North America or Australia, and New Zealand) were categorized as having a European (or Western/“white”) ethnicity. Youth whose families came from African, Middle Eastern, Asian or Latin American countries were classified as having a non-European (“non-white”) ethnicity. This distinction was made due to the different migration histories, cultures, and physical characteristics typically associated with these broad groups in Sweden. A similar classification has previously revealed differences between immigrant groups in labor market disadvantage in Sweden, suggestive of preferential treatment of immigrants from European and other Western countries (Jonsson 2007). A great advantage of the CILS4EU data is the ability to analyze both ethnic origin and immigrant generation, thus a five-category measure of immigrant status was formed representing: Swedish majority, second generation European background immigrants, second generation non-European, first generation European and first generation non-European immigrants.

Classroom Immigrant Density

Classroom immigrant density indicated the classroom ethnic composition. A continuous variable represented the proportion of students who were either first or second generation immigrants. A categorical measure was also formed reflecting low (0–20 %), moderate (21–49 %), and high (50–100 %) immigrant density. Categorical and continuous measures were generated because we were interested in both effects from contexts where immigrants comprised the majority versus minority (based on power imbalance theory) and also effects from linearly increasing density.

Control Variables

Several background characteristics that potentially confound the relationship between immigrant status and social exclusion were controlled for.

Family Structure

This measure reflected whether the student lived with both biological parents or not (separated or divorced parents). If information was missing from child-reports, information from the parental survey was used.

Parental Education

Parental education indicated the highest level of education attained by the biological parents that the participant regularly lives with. Records of educational attainment from official education registers included seven categories ranging from less than secondary education to post-graduate university studies. To maintain consistency with the “misfit” theoretical framework, the measure of parental education was centered around the class median. Thus, it represents parental education relative to that of their classmates.

Household Disposable Income

Household income was the total post-tax income of participants’ guardians according to tax registers, adjusted for family size by equivalization (dividing the income by the square root of the number of parents and children in the family). If parents lived in different households, the average of their incomes was used. To maintain consistency with the “misfit” theoretical framework, household income was also centered around the class median.

Cognitive Ability

Cognitive ability was measured using a timed pattern recognition test, considered the most culture-free cognitive test (see Weiss 2006). This was included as a covariate in the rejection analyses because a student’s cognitive ability may influence whether classmates would like to sit next to them. These scores were also centered to reflect participants’ level relative to the class median.

Class Size

The number of student in the class accounted for the structurally determined probability of receiving nominations.

Analysis Strategy

Stata 13 (Stata Corporation 2013) was used for all statistical analyses. Twenty-six cases that were judged to be unreliable due to implausible responses were removed as well as the sociometric nominations that they gave. A further 204 cases had incomplete data on one or more variables. This resulted in a core sample comprising 4795 students (in 251 classes in 129 schools), representing 96 % of the original sample. Additional exclusion criteria were applied for the rejection and isolation analyses using sociometric nominations. Sociometric data were screened with self-nominations and double-nominations (nominating the same classmate twice within friendship or rejection nominations) removed from the analyses. Cases missing complete data were removed only after their sociometric nominations were used to generate the measures of isolation and rejection. To ensure reliable measures, classes where less than 10 students or 70 % of students had completed the sociometric questionnaire were also excluded, consistent with recommended response rates for sociometric data (Marks et al. 2013). This resulted in a sub-sample of 4408 students for the isolation and 4237 students for the rejection analyses (171 participants did not complete the cognitive ability test).

Due to the clustering of students within classes, a series of two-level multilevel linear probability models (LPM) were performed at the individual and class-level. Exploratory analyses using multilevel logistic regression showed substantially similar results. However, LPM was chosen because unlike logistic regression, estimates are less influenced by omitted variables and unobserved heterogeneity, and can be more readily compared across models or groups and intuitively interpreted (see Mood 2010). A three-level modeling approach including school effects was not performed because the current theoretical focus was on classroom factors and exploratory analyses showed that no additional variance was captured at this level. Additionally, in some cases only one class participated from a given school. Official survey weights were used in all regression models to adjust for the oversampling of immigrant dense schools and non-response at the school, class, and individual levels.

Three models tested main effects for each of the three outcomes: rejection, isolation, and victimization. Model 1 presented the crude estimates for immigrant status. Model 2 then controlled for the family and individual background factors. Model 3 tested for the main effect of classroom immigrant density and class size in addition to immigrant status and all covariates. To test our hypotheses about the moderating effect of the social context, interactions between immigrant status and classroom immigrant density were then examined. Because power imbalance theory proposes that comprising the situational majority versus minority is of key importance, the categorical measure of immigrant density was of primary interest in all analyses. However, all interactions were also tested using the more parsimonious continuous measure of immigrant density.

Results

Table 1 shows the unweighted sample characteristics according to immigrant status, social exclusion, and the control variables. Approximately 30 % of participants had an immigrant background, including 10 % with a European background and 20 % with a non-European background (recall that these groups were oversampled). Although the majority of students attended classes with low immigrant density (49 %), due to strong ethnic school segregation the distribution varied widely according to immigrant status. For example, 65 % of majority youth, 16 % of the European, and 10 % of the non-European immigrants attended low immigrant dense classes. Conversely, 10 % of majority youth, 54 % of the European, and 65 % of non-European youth attended high immigrant dense classes. In relation to social exclusion, 26 % of youth were rejected, nearly 6 % were isolated and just under 10 % were victimized. The median disposable (equivalized) income corresponded to 26,784 USD, the majority of participants had at least one parent with a secondary education and lived with both parents. The analysis sample had a balanced gender distribution with 49 % males and 51 % females.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics for immigrant status, classroom immigrant density, social exclusion, and control variables (unweighted data, n = 4795)

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Immigrant status | Rejection (n = 4,237) | ||

| Swedish majority | 3318 (69.20) | No | 3131 (73.90) |

| Second generation European | 309 (6.44) | Yes | 1106 (26.10) |

| Second generation non-European | 655 (13.66) | Isolation (n = 4,408) | – |

| First generation European | 164 (3.42) | No | 4160 (94.37) |

| First generation non-European | 349 (7.28) | Yes | 248 (5.63) |

| Immigrant density–categorical | Victimization (n = 4,795) | ||

| Low 0–20 % | 2327 (48.53) | No | 4339 (90.49) |

| Moderate 21–49 % | 1238 (25.82) | Yes | 456 (9.51) |

| High 50–100 % | 1230 (25.65) | – | – |

| Immigrant density–continuousa | 22 (0–100) | ||

| Covariates | N (%) | Covariates | N (%) |

| Gender | Family structure | ||

| Male | 2352 (49.05) | Lives with both parents | 3197 (66.67) |

| Female | 2443 (50.95) | Other | 1598 (33.33) |

| Cognitive abilitya | 18 (0–27) | Household income ($US)a | 26784 (7–177,643) |

| Class sizea | 21 (6–32) | Parental educationa | 4 (1–7) |

| – | – | – |

Note a Continuous variable–median and range presented (before within-class centering if applicable); Class size for the sociometric-based analyses was 21 (10–31)

Main Effects of Immigrant Status on Social Exclusion

The main effects of immigrant status on the three aspect of social exclusion are shown in Table 2. Model 1 for rejection showed that all immigrant groups were at a greater risk of rejection compared to majority youth, with the difference ranging between 7 to 18 percentage points. The risk for first generation youth was greater than second generation irrespective of region of origin. Model 2 adjusted for the effects of key background factors and the effects for immigrant status reduced somewhat in this model. Model 3 then included immigrant density and the number of classmates as predictors, which showed a disadvantage for all immigrant groups. This is because attending a high immigrant dense classroom predicted a 12 percentage point reduced risk of rejection. In addition, being female as well as having stronger cognitive skills, higher household income, and higher parental education relative to classmates were each associated with a reduced likelihood of rejection.

Table 2.

Linear probability models predicting social exclusion

| Rejection (n = 4237) | Isolation (n = 4408) | Victimization (n = 4795) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Immigrant status | |||||||||

| Swedish majority | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Second generation European | .10 (.04)* | .09 (04)* | .12 (04)** | .03 (.03) | .02 (.03) | .03 (.03) | −.05 (.02)* | −.05 (.02)* | −.05 (.02)* |

| Second generation non-European | .07 (03)* | .04 (.03) | .08 (.03)* | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.02) | −.05 (.01)** | −.04 (.01)** | −.05 (.02)** |

| First generation European | .18 (.06)** | .16 (.06)** | .19 (.06)** | .01 (.03) | .01 (.03) | .01 (.03) | −.01 (.03) | −.01 (.03) | −.01 (.03) |

| First generation non-European | .12 (.04)** | .07 (.04)+ | .11 (.05)* | .08 (.03)** | .08 (.03)** | .08 (.03)** | .01 (.03) | .01 (03) | .01 (.03) |

| Gender-female | −.05 (.02)* | −.05 (.02)* | .01 (.01) | .01 (.01) | −.01 | −.01 (.01) | |||

| Cognitive ability | −.04 (.01)*** | −.04 (.01)*** | – | – | – | – | |||

| Other family structure | −.02 (.01) | −.02 (.02) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | .03 (.01)* | .03 (.03)* | |||

| Household income | −.02 (.01)* | −.02 (.01)* | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | .01 (.01) | .01 (.01) | |||

| Parental education | −.03 (.01)** | −.03 (.01)** | −.01 (.01)* | −.01 (.01)* | .01 (.01) | .01 (.01) | |||

| Immigrant density—categorical | |||||||||

| Low 0–20 % | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Moderate 21–49 % | −.04 (.02) | −.01 (.01) | .01 (.02) | ||||||

| High 50–100 % | −.12 (.03)*** | −.01 (.01) | .01 (.02) | ||||||

| Number of classmates | .01 (.01)+ | −.01 (.01)* | −.01 (.01) | ||||||

Note + p < .09; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

For isolation, model 1 showed that first generation immigrants of non-European background were significantly more likely to be isolated than majority youth. This result was maintained even after accounting for background factors in model 2, in which higher parental education predicted a lower likelihood of being isolated. As seen in model 3, no effects of immigrant density were observed, while greater class size reduced the likelihood of isolation. Follow-up analyses showed that the main effect for first generation non-European immigrants was primarily observed among recent immigrants—youth who migrated to Sweden after the age of 10, which is commonly the starting age for secondary school.

The main effects for victimization showed that second generation immigrant youth from both regions reported significantly less victimization than majority youth. This represented a likelihood that was five percentage points lower than majority youth. In model 2 having an alternative family structure predicted a greater likelihood of being victimized. However, model 3 revealed no effects of either immigrant density or class size for victimization.

Follow-up analyses tested the possible role of immigrant status in cumulative exclusion, using a measure that reflected co-occurring types of social exclusion (two or more). First generation immigrants irrespective of region showed an increased likelihood of cumulative exclusion that was marginally significant (b = .06 (.04), p < .10 and b = .06 (.03), p < .06, for the European and non-European regions, respectively). However, further examination revealed that this effect was also only observed among the recent immigrants.

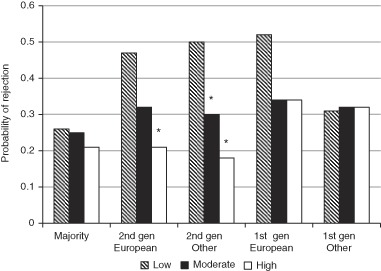

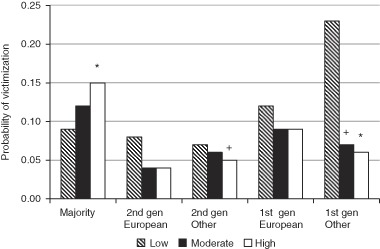

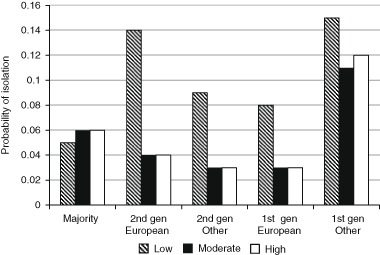

Interactions between Immigrant Status and Classroom Immigrant Density

The moderating effect of class immigrant density for each aspect of exclusion was then examined. Interaction effects are presented in Table 3, and Figs. 1–3 show the probability of exclusion according to immigrant status within low, moderate, and high immigrant dense classrooms (weighted data) after controlling for all background factors. Significant interactions (5 % level) are marked with an asterisk. Beginning with rejection, youth from all immigrant groups generally showed a greater likelihood than majority youth for rejection classes with low immigrant density (Fig. 1). For second generation immigrant youth from both regions, the likelihood of rejection was significantly lower in high immigrant dense classes, at about half the rate of low immigrant dense classes. These trends were qualified by significant interactions with the continuous measure of immigrant density, indicating less rejection for second generation European and non-European youth in increasingly immigrant dense classes. Immigrant density did not moderate the rejection of majority youth or the rejection of first generation immigrants from either region.

Table 3.

Significant interaction effects between immigrant status and classroom immigrant density

| Outcome | Interaction | Immigrant density | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical | Continuous | ||

| Rejection | Second generation European*high dense/increasing density | −.20 (.10)* | −.32 (.15)* |

| Rejection | Second generation non-European*moderate dense | −.18 (.09)* | |

| Rejection | Second generation non-European*high dense/increasing density | −.26 (.08)** | −.33 (.10)** |

| Victimization | Swedish majority*high dense/increasing density | .06 (.03)* | .10 (.04)*** |

| Victimization | Second generation non-European*high dense/increasing density | −.08 (.05)+ | −.13 (.06)* |

| Victimization | First generation non-European*moderate dense | −.19 (.10)+ | |

| Victimization | First generation non-European*high dense/increasing density | −.24 (.10)* | −.27 (.11)* |

Note + p < .09; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

Fig. 1.

Interactions between immigrant status and immigrant density for rejection

Fig. 3.

Interactions between immigrant status and immigrant density for victimization

All immigrant groups had higher rates of isolation in immigrant sparse classrooms (Fig. 2). While the pattern of higher risk was systematic, because isolation is a rather rare experience the differences to low immigrant dense classrooms did not reach statistical significance. However, analyses that tested only immigrant generation (by combining region of origin) showed that second generation immigrants experienced significantly less isolation in moderately dense (b = −10, p < .05) and high immigrant dense classes (b = −.10, p < .05) compared to low dense classes. These moderation effects were supported by a significant effect of linearly increasing immigrant density for second generation immigrants (b = −.13, p < .05).

Fig. 2.

Interactions between immigrant status and immigrant density for isolation

Moderation effects of immigrant density were also observed for victimization. Majority youth were more likely to be victimized in high immigrant dense than low dense classes, whereas immigrant youth showed the opposite pattern. First generation non-European immigrants had a much lower risk of being bullied in moderate and high dense classrooms. These findings were qualified by linear interaction terms showing increased risk for majority youth in increasingly immigrant dense classes and decreasing risk for non-European youth of second and first generations.

Sensitivity Analyses

Several sensitivity analyses were performed to ensure validity of the immigrant status measure. Parent-reported information on grandparents’ country of birth was available for a subsample of cases (56 %). Less than 1 % of immigrant youth were categorized as having a region of origin different to at least one their grandparents and none had more than two conflicts in categorization. Participants self-reported (subjective) ethnic identity was also compared with immigrant status. Less than 2 % (n = 90) of the immigrant sample reported a non-Swedish ethnic identity that was inconsistent with the region of origin. Analyses performed with these cases removed produced nearly identical estimates to the current findings. Thus, the region of origin classification using parents’ country of birth appeared to capture ethnic descent accurately. Robustness tests showed that the findings for subgroups within the two regions of origin generally followed a similar pattern. Dividing the regions into further subgroups resulted in too little statistical power and so the distinction between European and non-European background was applied. In addition, analyses with 28 adopted youth removed from the sample produced nearly identical estimates.

Alternative coding options for rejection were examined, including cut-offs representing at least one nomination (63 % of sample) or two or more nominations (40 %) and also continuous measures representing total nominations and nominations standardized within classes. These showed substantively similar results to the current estimates, supporting the robustness of the findings. A dichotomous measure of rejection was generated because nominations were heavily skewed and also to maintain consistency with the study’s other outcomes. We believe the selected cut-off avoided nuances (e.g., one nomination) while capturing a social dynamic that may be problematic for integration (higher, albeit not extreme nominations) and retaining adequate statistical power.

Discussion

In many European countries, increases in immigration and school ethnic segregation have raised challenges for promoting social cohesion and the social integration of youth. Social ecological theories point to the importance of social environments, such as the school class, and propose that individuals who are different to others are at greater risk of exclusion. Although previous research has identified victimization as a risk, young people can be socially marginalized by peers in a number of ways and so we tested a broader conceptualization of exclusion that captured multiple dynamics of marginalization. This included more subtle indicators of exclusion, namely the tendency to avoid sitting next to or not befriending someone. We, therefore, examined whether immigrant background functions as a determinant of “difference” invictimization, rejection, and isolation, as well as the moderating role of class immigrant density. The role of immigrant background was extended by testing both generation and region of origin. Furthermore, potential confounders for the relationship between immigrant status and exclusion were controlled for by also testing key background characteristics.

We used data on Swedish 14–15-year-olds (n = 4,795) to examine five key hypotheses. The results indicate that social exclusion is multi-faceted and support for the hypotheses varied somewhat across the outcomes. Hypothesis 1 proposed that if immigrant status generally signals “difference” then immigrant youth would be at higher risk of exclusion than majority youth. This expectation was supported by the higher rejection rates in all the immigrant groups and the greater risk for classroom isolation of first generation non-European immigrants. In relation to contextual effects, immigrant youth generally experienced more social exclusion in immigrant sparse classes and majority youth experienced more victimization in more immigrant dense classes, supporting hypothesis 2 and 3, respectively. Generally, second generation immigrants were at less risk of social exclusion than first generation immigrants in victimization and rejection, in line with hypothesis 4. However, non-European youth were not consistently at greater risk than European youth, giving only partial support for hypothesis 5. Greater exclusion of non-European youth was observed only for first generation immigrants in victimization and isolation (for which recent arrival was the driving force).

Overall, majority youth reported more victimization than second generation immigrants from either region, but similar rates to both first generation immigrant groups. As we did not find greater victimization of students of immigrant background overall, this indicates little general inter-ethnic hostility. Previous findings on victimization have been mixed, with some studies reporting that immigrant youth are at greater risk than native youth, particularly those of first generation (Hjern et al. 2013; Monks et al. 2008; Strohmeier et al. 2011; Sulkowski et al. 2014). However, others find that majority youth are bullied more (Strohmeier et al. 2008; Tippett et al. 2013; Vervoot et al. 2010) or little difference between majority and immigrant youth (Fandrem et al. 2009; McKenny et al. 2006; Vitoroulis et al. 2015). The current findings may shed light on inconsistent findings across studies by demonstrating that the definition of immigrant groups used in comparisons is important, as first generation but not second generation immigrants had victimization rates comparable to majority youth.

Consistent with the social misfit and power imbalance theories, being bullied was more common among first generation and second generation non-European youth in classrooms where they comprised a numerical minority. Likewise, majority youth also experienced more bullying when they were fewer (in higher immigrant dense classes). However, even in high immigrant dense classes, majority youth did not necessarily always comprise the absolute minority. For example, on average they made up 26 % of pupils in these classrooms, while first generation European and non-European youth made up 8 % and 18 %, respectively (and these groups may include several different ethnic groups). In comparison, low immigrant dense classes consisted of 92 % majority youth on average. Nevertheless, this difference in proportions appears to have influenced intergroup relations sufficiently—whether through power dynamics or perceptions of difference—so that majority youth’s vulnerability to victimization changed according to classroom ethnic composition.

All immigrant groups showed a greater risk than majority youth to be rejected. Although our measure captured the subtle mechanism of social avoidance, this finding is consistent with a recent Finnish study that found first and second generation immigrants were more likely to be disliked by their classmates than majority youth (Strohmeier et al. 2011). First generation immigrants in the current study were less preferred than second generation, indicating that this aspect of social exclusion decreases with time in the host country, presumably as a consequence of acculturation and language acquisition. Furthermore, regardless of immigrant status, respondents were less likely to be rejected in more immigrant dense schools. Hjern et al. (2013) found that Swedish students of all origins reported higher levels of well-being (including quality of peer relations, victimization, and school satisfaction) in high immigrant dense schools than low or medium dense schools. Future research should investigate which school or student characteristics may drive such patterns.

Overall, only small group differences were observed for isolation. Although first generation non-European immigrants appeared to be at greater risk than majority youth, follow-up analyses revealed that this effect was primarily observed for youth who had migrated to Sweden since the start of secondary school (after age 10). This demonstrates the importance of identifying time of immigration, even within first generation immigrants. Closson et al. (2014) found that recent immigrants (arrival within 2 years) in Canada were at increased risk of discrimination, feeling unsafe, and fearing victimization at school than youth who had migrated earlier in childhood. Our findings are partially consistent with research indicating that immigrant children, particularly first generation, have fewer friends and are less accepted than majority youth (Strohmeier and Spiel 2003; Von Grünigen et al. 2010), if we qualify this to concern immigrant sparse school classes. In these classes, we found a systematic pattern suggesting that both first and second generation immigrants have higher risks of being isolated. This is in line with a recent study of Danish youth that found being an ethnic minority in class is associated with greater loneliness (Madsen et al. 2016).

The patterns observed according to immigrant generation and region of origin highlight the importance of acculturation and ethnic discrimination processes for different aspects of social exclusion. While our finding that pupils of immigrant background are more socially excluded points to challenges for integration, the results showing that second generation youth tend to be at lower risk than first generation youth suggests that groups do get more integrated over time. Another positive result is that few differences were observed between those with immigrant origins geographically, culturally, and phenotypically closer to Sweden (European and other Western countries), and those who come from non-European and non-Western countries. Our findings largely point to the importance of cultural and language familiarity, as well as social and economic resources in explanations for exclusion, rather than “race” per se. In addition, by using three indicators of social exclusion, we found that while immigrant youth were generally at higher risk of social exclusion, a pattern of cumulative risk was only observed for very recent arrivals.

Two key contributions of the current study were to demonstrate how immigrant status was related to different aspects of social exclusion at school and to provide insights on the role of classroom ethnic composition. Immigrants are a heterogeneous group, and unlike most previous studies, the over-sampling of immigrant dense schools and detailed data on family background permitted an examination of both region of origin and immigrant generation. This captured different cultures, migration histories, labor market integration, and exposure to Swedish language and culture typically associated with these groups in Sweden. Nevertheless, even with the current large sample, we were unable to examine variation within these two regions of origin. Our findings indicated that first generation immigrant youth are particularly vulnerable to isolation and to bullying in immigrant sparse settings, especially non-European immigrants. Recent immigrants were identified for robustness tests, but due to the small numbers in this subsample they were not analyzed in further detail. Future studies with larger sample sizes should replicate the current findings, particularly the results observed for isolation. This would also enable a more detailed examination of country of origin and longitudinal studies could corroborate whether longer host country exposure reduces the risk of rejection.

Future studies could also work to more clearly identify conditions and mechanisms that minimize the salience of immigrant status in social exclusion. For example, a positive classroom atmosphere, characterized by classmate support, has been shown to protect both majority and immigrant youth from effects of immigrant density on victimization (Walsh et al. 2016). Conceptualizations of classroom ethnic composition can take many forms and the current study used the proportion of non-majority youth. However, it can also be examined according to classroom diversity, which reflects the ethnic heterogeneity (e.g., Putnam 2007). Exploratory analyses found no main effects of diversity once the influence of immigrant density was accounted. In low immigrant dense classes there was high collinearity between density and diversity but the correlation substantially weakened with increasing immigrant density. Previous studies have also shown immigrant density to be a stronger predictor of social exclusion than diversity (Agirdag et al. 2011). However, the interaction between immigrant density and diversity may be particularly important for immigrant dense schools in countries with a heterogeneous immigrant population such as Sweden. In addition, the impact of having classmates of the same-origin or same-immigrant generation would also shed more light on ethnic composition effects and exclusion from within the immigrant population, especially in regards to rejection.

The current study focused specifically on social exclusion among peers in the school class context. An important question regards the extent to which exclusion extends beyond this environment. Social exclusion by classmates may represent a generalized interpersonal disadvantage with difficulties across multiple settings or it may be limited to the school context. Thus, future research should also consider youth’s out-of-school social activities and interpersonal relationships, as well as the role of neighborhood ethnic segregation to further understand the scope of social exclusion.

Conclusion

The current study revealed a complex picture of social integration for both immigrant and majority youth. The findings demonstrated that in addition to victimization, more subtle or even implicit forms of social exclusion present challenges to the integration of immigrant youth. Immigrant status was associated with multiple aspects of social exclusion among peers and the ethnic composition of the school class played an important role in defining which youth were excluded. The findings underline the importance of considering immigrant generation when addressing ethnic segregation in schools, and highlight the social difficulties of recent immigrants. Although ethnic segregation appears to have some protective effects in contexts with similar others, it may inhibit integration and impede immigrant youth’s network resources in the long run. More work is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms, such as hierarchies related to social or economic resources, language, behavioral or cultural competencies, and the likelihood of social exclusion of immigrants by other immigrant youth. Efforts are needed to help educators identify socially excluding behavior that may seem innocuous but can have negative secondary effects. Strategies that promote perceptions of similarity based on interests, skills, and social status may help.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank New Opportunities for Research Funding Agency Co-operation in Europe (NORFACE) for financing the CILS4EU project and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare (FORTE) (grant no. 2012–1741) for financing this study.

Funding

The current study was funded by a grant from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare (FORTE) (grant no. 2012–1741). The CILS4EU project was funded by the New Opportunities for Research Funding Agency Co-operation in Europe (NORFACE).

Biographies

Stephanie Plenty

is a post-doctoral researcher at the Institute for Future Studies and at the Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University, Sweden. Her research interests include social relationships and social integration in relation to adolescent well-being and positive development.

Jan O. Jonsson

is Official Fellow of Nuffield College, Oxford, Professor of Sociology at the Swedish Institute for Social Research, and affiliated with Institute for Futures Studies. Among his research interests are social stratification, the welfare and living conditions of children and youth, and ethnic integration.

Authors’ Contributions

SP conceived the study, performed the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript; JJ was involved in the study’s design, theoretical framework, and interpretation of the data. Both authors drafted the manuscript, revisions, and approved the final version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The current study received approval from the Regional Ethics Committee, Stockholm. Approval reference number 2010/1557–31/5.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual students included in the study and from their parents.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10964-016-0564-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Agirdag O, Demanet J, Van Houtte M, Van Avermaet P. Ethnic school composition and peer victimization: a focus on the interethnic school climate. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2011;35(4):465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alba, R., & Nee, V. (2009). Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Harvard University Press. http://site.ebrary.com.ezp.sub.su.se/lib/sthlmub/detail.action?docID=10326131.

- Almquist Y. Social isolation in the classroom and adult health: a longitudinal study of a 1953 cohort. Advances in Life Course Research. 2011;16(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2010.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baerveldt C, Zijlstra B, De Wolf M, Van Rossem R, Van Duijn MA. Ethnic boundaries in high school students’ networks in Flanders and the Netherlands. International Sociology. 2007;22(6):701–720. doi: 10.1177/0268580907082248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellmore A, Nishina A, You JI, Ma TL. School context protective factors against peer ethnic discrimination across the high school years. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;49(1-2):98–111. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. Friends’ influence on students’ adjustment to school. Educational Psychologist. 1999;34(1):15–28. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep3401_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology. 1997;46(1):5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P. Immigrant youth: acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology. 2006;55(3):303–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00256.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin M, Dodge KA, Coie JD. Individual-group behavioral similarity and peer status in experimental play groups of boys: the social misfit revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(2):269. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B. (2004). Adolescents relationships with peers. In Richard M. Lerner & Laurence D. Steinberg (Eds.) Handbook of adolescent psychology (2nd edn., pp. 363–394). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Böhlmark A, Holmlund H, Lindahl M. Parental choice, neighbourhood segregation or cream skimming? an analysis of school segregation after a generalized choice reform. Journal of Population Economics. 2016;29(4):1155–1190. doi: 10.1007/s00148-016-0595-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Closson LM, Darwich L, Hymel S, Waterhouse T. Ethnic discrimination among recent immigrant adolescents: variations as a function of ethnicity and school context. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2014;24(4):608–614. doi: 10.1111/jora.12089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham Y, Baron AS, Banaji MR. From American city to Japanese village: A cross‐cultural investigation of implicit race attitudes. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1268–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat (2011). Migrants in Europe: A statistical portrait of the first and second generation. Publications Office of the European Union, 2011.

- Fandrem H, Strohmeier D, Roland E. Bullying and victimization among native and immigrant adolescents in Norway the role of proactive and reactive aggressiveness. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29(6):898–923. doi: 10.1177/0272431609332935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuin J, Van Geel M, Ziberna A, Vedder P. Ethnic preferences in friendships and casual contacts between majority and minority children in the Netherlands. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2014;41:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S. Peer victimization in school exploring the ethnic context. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15(6):317–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00460.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths JA, Nesdale D. In-group and out-group attitudes of ethnic majority and minority children. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2006;30(6):735–749. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Guerra NG. The roles of ethnicity and school context in predicting children’s victimization by peers. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(2):201–223. doi: 10.1023/A:1005187201519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjalmarsson S, Mood C. Do poorer youth have fewer friends? The role of household and child economic resources in adolescent school-class friendships. Children and Youth Services Review. 2015;57:201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hjern A, Rajmil L, Bergström M, Berlin M, Gustafsson PA, Modin B. Migrant density and well-being—A national school survey of 15-year-olds in Sweden. The European Journal of Public Health. 2013;23(5):823–828. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmlund, H. J., Häggblom, E., Lindahl, S., Martinson, A., Sjögren, U., Vikman och B. Öckert (2014). “Decentralisering, skolval och fristående skolor: Resultat och likvärdighet i svensk skola” [Decentralization, school choice and independent schools: Results and equivalence in the Swedish school], IFAU report 2014:25.

- Hong JS, Espelage DL. A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2012;17(4):311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MF, Barth JM, Powell N, Lochman JE. Classroom contextual effects of race on children’s peer nominations. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1325–1337. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, J. O. (2007). The farther they come, the harder they fall? First and second generation immigrants in the Swedish labour market. In A. F. Heath & S. Y. Cheung (Eds.), Unequal chances: Ethnic minorities in Western labour markets (pp. 451–505). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Juvonen J, Nishina A, Graham S. Ethnic diversity and perceptions of safety in urban middle schools. Psychological Science. 2006;17(5):393–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalter F, Heath AF, Hewstone M, Jonsson JO, Kalmijn M, Kogan I, van Tubergen F. The children of immigrants longitudinal survey in four European countries (CILS4EU): Motivation, aims, and design. Mannheim: Universität Mannheim; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- LaFontana KM, Cillessen AH. Developmental changes in the priority of perceived status in childhood and adolescence. Social Development. 2010;19(1):130–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00522.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S. R., & Killen, M. (Eds.) (2010). Intergroup attitudes and relations in childhood through adulthood. Oxford University Press. http://site.ebrary.com.ezp.sub.su.se/lib/sthlmub/detail.action?docID=10211886.

- Madsen KR, Damsgaard MT, Rubin M, Jervelund SS, Lasgaard M, Walsh S, Holstein BE. Loneliness and ethnic composition of the school class: a nationally random sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016;45(7):1350–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0432-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks PE, Babcock B, Cillessen AH, Crick NR. The effects of participation rate on the internal reliability of peer nomination measures. Social Development. 2013;22(3):609–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00661.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, C. M., Kuo, S. I-C., & Masten, A. S. (2011). Developmental tasks across the lifespan. In K. L. Fingerman, C. A. Berg, J. Smith, & T. C. Antonucci (Eds.), Handbook of lifespan development (pp. 117–140). New York, NY: Springer.

- McKenney KS, Pepler D, Craig W, Connolly J. Peer victimization and psychosocial adjustment: the experiences of Canadian immigrant youth. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology. 2006;9(4):239–264. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:415–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez JJ, Bauman S, Guillory RM. Bullying of Mexican immigrant students by Mexican American students: an examination of intracultural bullying. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2012;34(2):279–304. doi: 10.1177/0739986311435970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monks CP, Ortega-Ruiz R, Rodríguez-Hidalgo AJ. Peer victimization in multicultural schools in Spain and England. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2008;5(4):507–535. doi: 10.1080/17405620701307316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mood C. Logistic regression: why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review. 2010;26(1):67–82. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcp006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mood C, Jonsson JO. “Trends in child poverty in Sweden: parental and child reports”. Child Indicators Research. 2016;9(3):825–854. doi: 10.1007/s12187-015-9337-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motti-Stefanidi F, Pavlopoulos V, Obradović J, Dalla M, Takis N, Papathanassiou A, Masten AS. Immigration as a risk factor for adolescent adaptation in Greek urban schools. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2008;5(2):235–261. doi: 10.1080/17405620701556417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Graham S. Early puberty, peer victimization, and internalizing symptoms in ethnic minority adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25(2):197–222. doi: 10.1177/0272431604274177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Östberg V, Modin B. Status relations in school and their relevance for health in a life course perspective: findings from the Aberdeen children of the 1950’s cohort study. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66(4):835–848. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta‐analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;38(6):922–934. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. E pluribus unum: diversity and community in the twenty-first century. The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies. 2007;30(2):137–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2007.00176.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin DB, Way N, Rana M. The “model minority” and their discontent: Examining peer discrimination and harassment of Chinese American immigrant youth. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2008;2008(121):27–42. doi: 10.1002/cd.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark TH, Flache A. The double edge of common interest: ethnic segregation as an unintended byproduct of opinion homophily. Sociology of Education. 2012;85(2):179–199. doi: 10.1177/0038040711427314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corporation . Stata statistical software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sweden (2013). http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Artiklar/Vart-femte-barn-har-utlandsk-bakgrund/.

- Strohmeier D, Kärnä A, Salmivalli C. Intrapersonal and interpersonal risk factors for peer victimization in immigrant youth in Finland. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(1):248. doi: 10.1037/a0020785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohmeier D, Spiel C. Immigrant children in Austria: Aggressive behavior and friendship patterns in multicultural school classes. Journal of Applied School Psychology. 2003;19(2):99–116. doi: 10.1300/J008v19n02_07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strohmeier D, Spiel C, Gradinger P. Social relationships in multicultural schools: bullying and victimization. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2008;5(2):262–285. doi: 10.1080/17405620701556664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowski ML, Bauman S, Wright S, Nixon C, Davis S. Peer victimization in youth from immigrant and non-immigrant US families. School Psychology International. 2014;35(6):649–669. doi: 10.1177/0143034314554968. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology. 1982;33(1):1–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.33.020182.000245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thijs J, Verkuyten M, Grundel M. Ethnic classroom composition and peer victimization: The moderating role of classroom attitudes. Journal of Social Issues. 2014;70(1):134–150. doi: 10.1111/josi.12051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tippett N, Wolke D, Platt L. Ethnicity and bullying involvement in a national UK youth sample. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36:639–649. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . Children in immigrant families in eight affluent countries. Their family, national and international context. Florence: The UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten M, Thijs J. Racist victimization among children in the Netherlands: The effect of ethnic group and school. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2002;25(2):310–331. doi: 10.1080/01419870120109502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort MH, Scholte RH, Overbeek G. Bullying and victimization among adolescents: The role of ethnicity and ethnic composition of school class. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9355-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitoroulis, I., Brittain, H., & Vaillancourt, T. (2015). School ethnic composition and bullying in Canadian schools. International Journal of Behavioral Development. doi:10.1177/0165025415603490.

- Von Grünigen R, Perren S, Nägele C, Alsaker FD. Immigrant children’s peer acceptance and victimization in kindergarten: the role of local language competence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2010;28(3):679–697. doi: 10.1348/026151009X470582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SD, De Clercq B, Molcho M, Harel-Fisch Y, Davison CM, Madsen KR, Stevens GW. The relationship between immigrant school composition, classmate support and involvement in physical fighting and bullying among adolescent immigrants and non-immigrants in 11 countries. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016;45(1):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis RH. Grundintelligenztest Skala 2 Revision (CFT–20R) Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T, Rodkin PC. African American and European American children in diverse elementary classrooms: Social integration, social status, and social behavior. Child Development. 2011;82(5):1454–1469. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D, Copeland WE, Angold A, Costello EJ. Impact of bullying in childhood on adult health, wealth, crime, and social outcomes. Psychological Science. 2013;24(10):1958–1970. doi: 10.1177/0956797613481608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JC, Giammarino M, Parad HW. Social status in small groups: Individual–group similarity and the social “misfit”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50(3):523. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.