Abstract

Azotobacter vinelandii, a strict aerobic, nitrogen fixing bacterium in the Pseudomonadaceae family, exhibits a preferential use of acetate over glucose as a carbon source. In this study, we show that GluP (Avin04150), annotated as an H+-coupled glucose-galactose symporter, is the glucose transporter in A. vinelandii. This protein, which is widely distributed in bacteria and archaea, is uncommon in Pseudomonas species. We found that expression of gluP was under catabolite repression control thorugh the CbrA/CbrB and Crc/Hfq regulatory systems, which were functionally conserved between A. vinelandii and Pseudomonas species. While the histidine kinase CbrA was essential for glucose utilization, over-expression of the Crc protein arrested cell growth when glucose was the sole carbon source. Crc and Hfq proteins from either A. vinelandii or P. putida could form a stable complex with an RNA A-rich Hfq-binding motif present in the leader region of gluP mRNA. Moreover, in P. putida, the gluP A-rich Hfq-binding motif was functional and promoted translational inhibition of a lacZ reporter gene. The fact that gluP is not widely distributed in the Pseudomonas genus but is under control of the CbrA/CbrB and Crc/Hfq systems demonstrates the relevance of these systems in regulating metabolism in the Pseudomonadaceae family.

Introduction

Azotobacter vinelandii is a gamma proteobacterium belonging to the Pseudomonadaceae family1. Although A. vinelandii is phylogenetically related to Pseudomonas species, it possesses distinctive features that clearly separates it from the genus Pseudomonas, such as its capacity to differentiate and form dormant cysts that are resistant to drought, its strict aerobic metabolism and its capacity to fix nitrogen under aerobic conditions2, 3. A. vinelandii produces two polymers of biotechnological importance, the exo-polysaccharide alginate and the intracellular polyester polyhydroxybutyrate4. A. vinelandii can use many carbohydrates, alcohols and salts of organic acids for growth; however, it is unable to grow using amino acids as the sole carbon source5. Similar to Pseudomonas spp., A. vinelandii does not have a functional glycolytic pathway, but instead relies on the Entner-Doudoroff pathway (EDP) for glucose utilization6. This bacterium exhibited diauxic growth when grown in a medium containing both acetate and glucose7–9. In this condition, acetate was used as the primary carbon source. Once the acetate was exhausted, glucose uptake was initiated, indicating that acetate repressed the synthesis of the glucose transport system. The tricarboxylic acid intermediates citrate, isocitrate and 2-oxo-glutarate also inhibited glucose utilization9, suggesting the existence of a carbon catabolite repression (CCR) process in A. vinelandii similar to that in Pseudomonas species.

CCR is a global regulatory system that allows the selective assimilation of a preferred compound among a mixture of several potential carbon sources. Unlike Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, the preferred carbon sources for bacteria in the genus Pseudomonas are some organic acids and amino acids rather than glucose10. In Pseudomonas species the process of CCR is elicited mainly through a regulatory system based on the Crc and Hfq proteins and one or more small RNAs (sRNAs) of the CrcZ, CrcY or CrcX family that antagonize the effect of these regulatory proteins11–14. A two-component system, composed of the histidine kinase (HK) CbrA and the response regulator (RR) CbrB, heads this regulatory pathway by directly activating the transcription of sRNAs from RpoN-dependent promoters14, 15. The Crc and Hfq proteins play a central role in CCR in Pseudomonas spp., promoting the inhibition of translation of RNAs containing an AAnAAnAA motif, called the CA motif (for Catabolite Activity), which is close to the translation initiation site14, 16–19. The RNA chaperone Hfq recognizes and binds these A-rich motifs, the role of Crc being to stabilize the ribonucleoprotein complexes formed12, 13, 20. For this reason, the CA motifs are also known as A-rich Hfq-binding motif. As noted above, glucose is not the preferred carbon source for Pseudomonas. In fact, Crc and Hfq inhibit the expression of the OprB1 porin for the uptake of glucose, of the inner membrane glucose transporter GtsABC, and of several genes required for glucose assimilation in P. putida when grown in a rich medium21.

In the present study, we investigated the regulation of glucose uptake in A. vinelandii and the role of the CbrA/CbrB and Crc/Hfq systems in the CCR process. Analysis of the genome sequence revealed that A. vinelandii lacks the inner membrane glucose transporter GtsABC that is present in Pseudomonas spp. Our results indicated that the gene gluP encodes the glucose transporter and that translation of the gluP mRNA is under catabolite repression control thorugh the CbrA/CbrB and Crc/Hfq regulatory systems in A. vinelandii. The gluP A-rich Hfq-binding motif was functional when introduced into P. putida as its presence promoted translational inhibition of a lacZ reporter gene.

Results

The histidine kinase CbrA is necessary for the utilization of glucose

Previous studies demonstrated the preferential use of acetate over glucose in the A. vinelandii strain OP8, 9, a derivative of the O strain that is unable to produce the exo-polysaccharide alginate2. However, the underlying mechanism of this catabolic repression was unknown. In a random miniTn5 mutant bank derived from the wild-type strain AEIV, we identified mutant GG15 by its alginate-over-producing phenotype on plates of minimal Burk’s-sucrose medium. This mutant carries the miniTn5 insertion within codons 660 and 661 of a gene that is similar to cbrA, which encodes an HK that forms part of the CbrA/CbrB two-component system present in Pseudomonas spp. As explained in the Introduction, the CbrA/CbrB regulatory system plays a key role in Pseudomonas catabolite repression together with Crc and Hfq proteins, and the CrcZ/CrcY sRNAs.

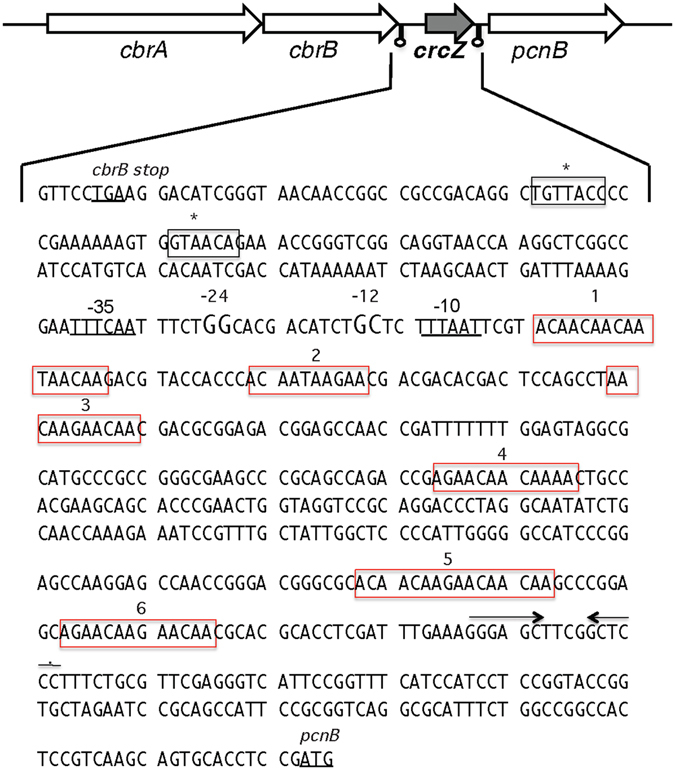

Genes encoding all components of the CbrA/CbrB and Crc/Hfq systems are present in the A. vinelandii genome. A cbrB gene (Avin42680), encoding the CbrB cognated RR, and the gene for the sRNA CrcZ, are located immediately downstream of cbrA (Avin42670) (Fig. 1). The predicted CbrA and CbrB proteins are highly similar (>77% identity) to their homologues from P. aeruginosa and P. putida. An in-silico analysis identified a putative σ70 promoter upstream of the cbrB gene, which has also been identified in P. aeruginosa 22. The A. vinelandii genome also contains genes for the sRNAs CrcZ and CrcY11. The CrcZ sRNA shows 68% identity to the P. putida and P. aeruginosa CrcZ and contains six putative A-rich Hfq-binding motifs (AANAANAA) (Fig. 1). The predicted secondary structure shows that these A-rich motifs are located on the loops (Supplementary Fig. S1). The A. vinelandii crcY gene was located in the intergenic region in between Avin04820 and Avin04790 ORFs, which encode hypothetical proteins (Supplementary Fig. S2). CrcY contains five putative A-rich Hfq-binding motifs, and four of them are predicted to be located on the loops (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 1.

Genome context and nucleotide sequence of the A. vinelandii CrcZ sRNA. Terminators are indicated by small stem-loops. The six CrcZ A-rich Hfq-binding motifs are indicated by red boxes. The −12 and −24 regions of the predicted RpoN promoter and putative sequences recognized by CbrB (black boxes) are indicated. The predicted −10 and −35 regions of an RpoD promoter are underlined. Inverted repeats at the end of CrcZ are denoted by solid arrows.

Genes crc (Avin02870) and hfq (Avin07540) were also identified in the A. vinelandii genome. The Crc and Hfq proteins showed 88 and 93% identity, respectively, to their P. aeruginosa homologues. The genes are in regions highly conserved among several Pseudomonas species. A BLAST search indicated that crcZ, crcY, crc and the hfq genes are present in the genome of the A. vinelandii strain CA-6 and in Azotobacter chroococcum within similar genomic contexts.

As mentioned above, the CbrA-null strain GG15 over-produced alginate when cultivated on plates of minimal Burk’s-sucrose medium. In fact, the GG15 mutant showed five-times higher alginate levels than the wild type strain AEIV23. Since this polymer is synthesized from fructose-6-phosphate it competes for the available carbon source affecting cell growth24. Thus, the alginate phenotype of mutant GG15 would prevent a reliable assessment of the CbrA role on the growth on different carbon sources. For this reason, the effect of the HK CbrA on the CCR process was evaluated in an alg-negative genetic background. We used strain AEalgD, a derivative of strain AEIV that carries an algD::Km mutation, and mutant AH1, an AEalgD derivative carrying a cbrA::miniTn5 mutation.

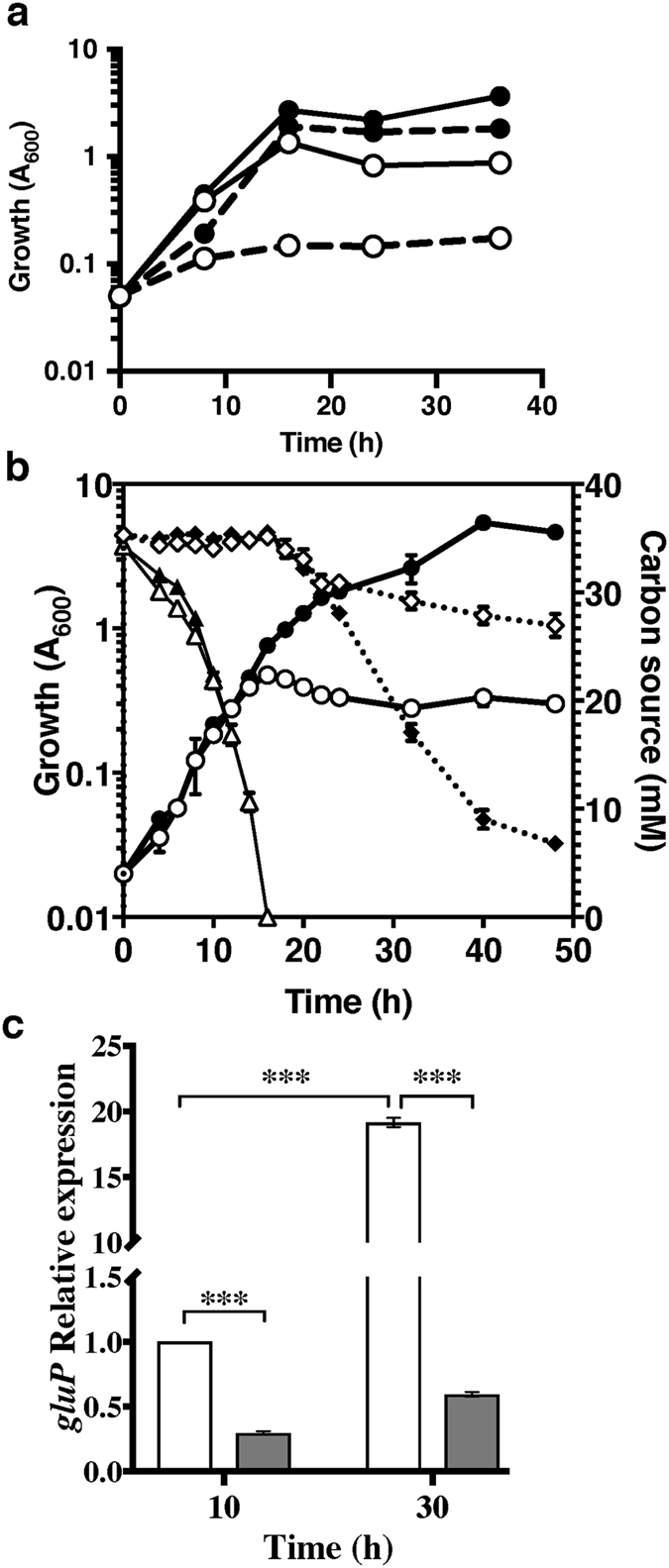

As shown in Fig. 2a, both AEalgD and AH1 strains grew with sucrose as the sole carbon source. However, strain AH1 was unable to grow on glucose, indicating that the CbrA HK was necessary for the utilization of this compound in A. vinelandii. Figure 2b shows that the assimilation of glucose did not occur in the presence of acetate in the AEalgD strain, which was consistent with previous reports indicating diauxic growth in A. vinelandii in medium supplemented with acetate and glucose. However, after acetate consumption, glucose utilization was initiated. In contrast, the cbrA mutant AH1 grew on acetate plus glucose, but glucose assimilation was abrogated and growth ceased as soon as acetate was consumed (Fig. 2b). The inability to use glucose was also observed for an AEalgD derivative cbrA::Sp mutant constructed by reverse genetics (data not shown). These results indicate that the HK CbrA was involved in the control of CCR in A. vinelandii. Because the CbrA/CbrB system is needed in P. putida and P. aeruginosa for the synthesis of the CrcZ/CrcY sRNAs, which in turn antagonize the effects of Crc/Hfq13, 20, 25, the lack of CbrA in A. vinelandii could be generating strong Crc/Hfq-dependent repression. We next analysed this possibility.

Figure 2.

The HK CbrA is necessary for glucose utilization. (a) Growth kinetics of the reference strain AEalgD (algD::Km) (closed symbols) and its derivative mutant AH1 (cbrA::miniTn5) (open symbols) in liquid Burk’s minimal medium amended with 50 mM glucose (dashed lines) or 2% sucrose (solid lines). (b) Growth kinetics (circles), and acetate (triangles) or glucose (diamonds) consumption during the culture of the reference strain AEalgD (algD::Km) (closed symbols) or its derivative mutant AH1 (cbrA::miniTn5) (open symbols) in Burk’s minimal medium supplemented with both 30 mM glucose and 30 mM acetate as carbon sources. (c) gluP mRNA levels determined by qRT-PCR analysis in strain AEalgD (white columns) and in mutant AH1 (grey columns) in the diauxic growth of panel (b). Total RNA was extracted from cells at the indicated times. The bars of standard deviation from three independent experiments are shown. Significant differences were analysed by t-test. Statistical significance is indicated (***p < 0.001).

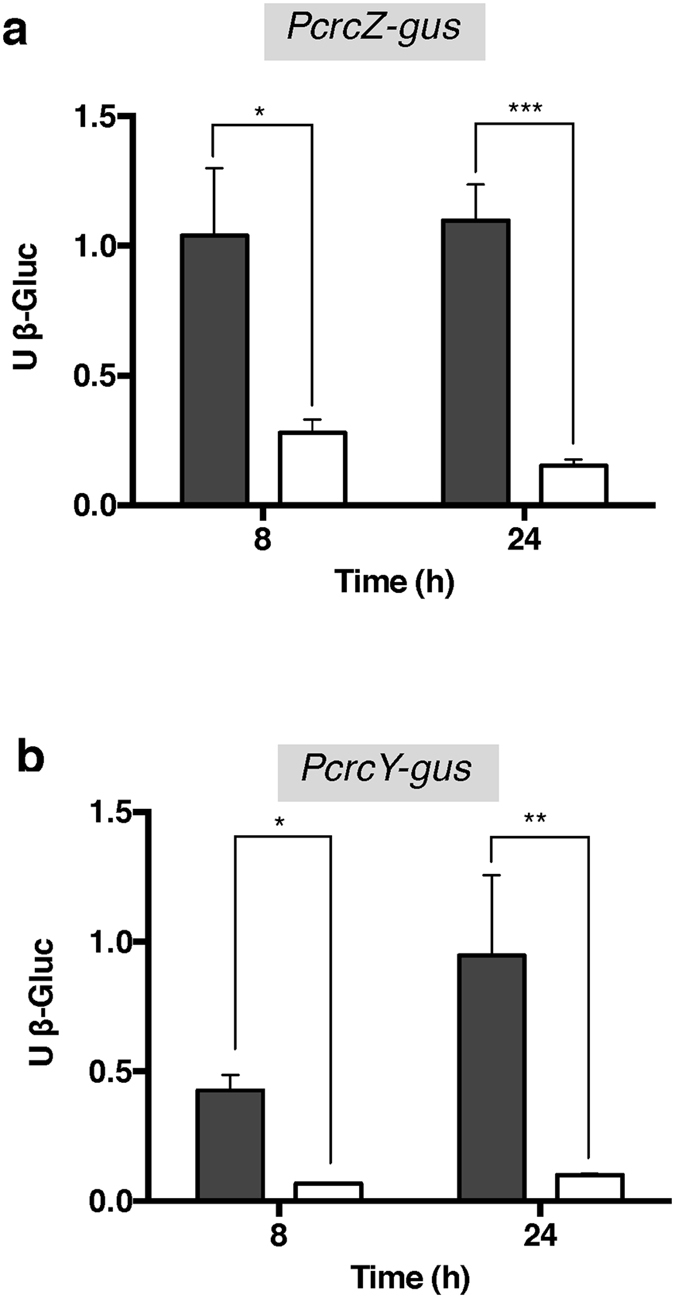

The two-component system CbrA/B was necessary for the transcription of the sRNAs CrcZ and CrcY

To determine whether expression of the sRNAs CrcZ and CrcY in A. vinelandii was under the control of the two-component system CbrA/CbrB, transcriptional fusions of the regulatory regions of crcZ and crcY with the reporter gene gusA were constructed (PcrcZ-gusA and PcrcY-gusA, respectively). Derivatives of the wild type strain AEIV and mutant cbrA carrying these gene fusions were cultured in Burk’s-sucrose medium, and the activity of ß-glucuronidase was measured at the exponential (8 h) and stationary (24 h) phases of growth. As shown in Fig. 3, transcription of both sRNAs was dependent on the HK CbrA as in the cbrA mutant the activity of the PcrcY-gusA and PcrcZ-gusA transcriptional fusions was reduced at least four-fold during the exponential and stationary growth phases. Analysis of the CrcZ regulatory region allowed the identification of conserved residues characteristic of RpoN dependent promoters located at 13 (−12) and 25 (−24) nt upstream of the first A-rich Hfq-binding motif. Additionally, putative binding sites for the RR CbrB at positions −125 and −145 relative to the first A-rich Hfq-binding motif were identified (Fig. 1a). The regulatory region of crcY also showed conserved sequences for an RpoN-dependent promoter as well as sequences recognized by the RR CbrB at similar positions (Supplementary Fig. S2). Together, these results imply that the two-component CbrA/CbrB system activates CrcZ and CrcY transcription, as has been described in several Pseudomonas species.

Figure 3.

Effect of the HK CbrA on crcZ and crcY gene expression. Expression of crcZ and crcY genes was assessed by PcrcZ-gusA (a) and PcrcY-gusA (b) transcriptional fusions, respectively. These transcriptional fusions were tested in wild type and cbrA genetic backgrounds. The strains used were: AE-Zgus (wild type; black bars) and CbrA-Zgus (cbrA::Sp; white bars) (a); AE-Ygus (wild type; black bars) and CbrA-Ygus (cbrA::Sp; white bars) (b). Cultures were developed in minimal Burk’s-sucrose medium. Aliquots were taken at the indicated times and ß-glucuronidase activity was measured. The bars of standard deviation from three independent experiments are shown. Significant differences were analysed by t-test. Statistical significance is indicated (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 or ***p < 0.001).

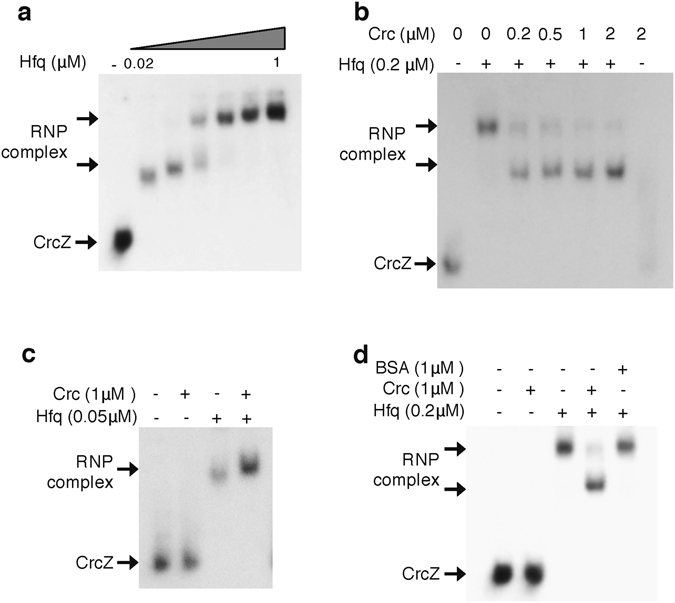

The sRNA CrcZ can bind to the Hfq protein and Crc facilitates this interaction

We next investigated the ability of CrcZ to form a complex with the purified His-Hfq and Crc proteins from A. vinelandii using RNA electrophoretic-mobility shift assays (EMSAs). To avoid E. coli Hfq contaminations His-Hfq and Crc proteins were purified from the Hfq-null E. coli expression strain MG165512. Radioactively labelled CrcZ was synthesized by in vitro transcription. Binding reactions were performed using the protocols reported for P. putida, in the presence of an excess of tRNA allowing specific binding of the Hfq and Crc proteins16, 18. Hfq generated a stable complex with CrcZ at concentrations as low as 0.02 μM (Fig. 4a). As the concentration of Hfq increased, the formed complex showed lower mobility consistent with the presence of several A-rich Hfq-binding motifs in CrcZ. This complex also showed increased stability based on the intensity of the shifted band (Fig. 4a). The Crc protein alone was unable to form a stable complex with CrcZ, even at high concentrations (Fig. 4b). However, at 0.2 µM Hfq, the presence of Crc changed the migration pattern of the Hfq-CrcZ complex, which showed a faster electrophoretic mobility, suggesting the formation of a tripartite CrcZ-Hfq-Crc complex (Fig. 4b). At a lower Hfq concentration (0.05 µM), the presence of Crc also stabilized the Hfq-RNA complex formed (Fig. 4c). The presence of Crc but not that of bovine serum albumin (BSA) changed the migration pattern of the shifted band (Fig. 4d), implying that Crc binds to the CrcZ-Hfq complex in a specific manner. Collectively these results indicate that the CbrA/CbrB and Crc-Hfq systems in A. vinelandii and Pseudomonas spp. operate mechanistically in a similar manner.

Figure 4.

Hfq-Crc proteins form a stable ribonucleoprotein complex with CrcZ. Ribonucleoprotein complexes formed in the presence of the sRNA CrcZ and increasing concentrations of Hfq (0, 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 and 1 µM) (a) or in the presence of both Crc and Hfq (b and c). In (d) Crc was substituted by 1 µM of bovine serum albumin (BSA). Crc and Hfq were added at the indicated concentrations (expressed as monomers and hexamers respectively). RNA and protein-RNA complexes were resolved in a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The position of free RNA, and of the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes detected, is indicated.

Over-expression of Crc in trans diminishes growth on glucose

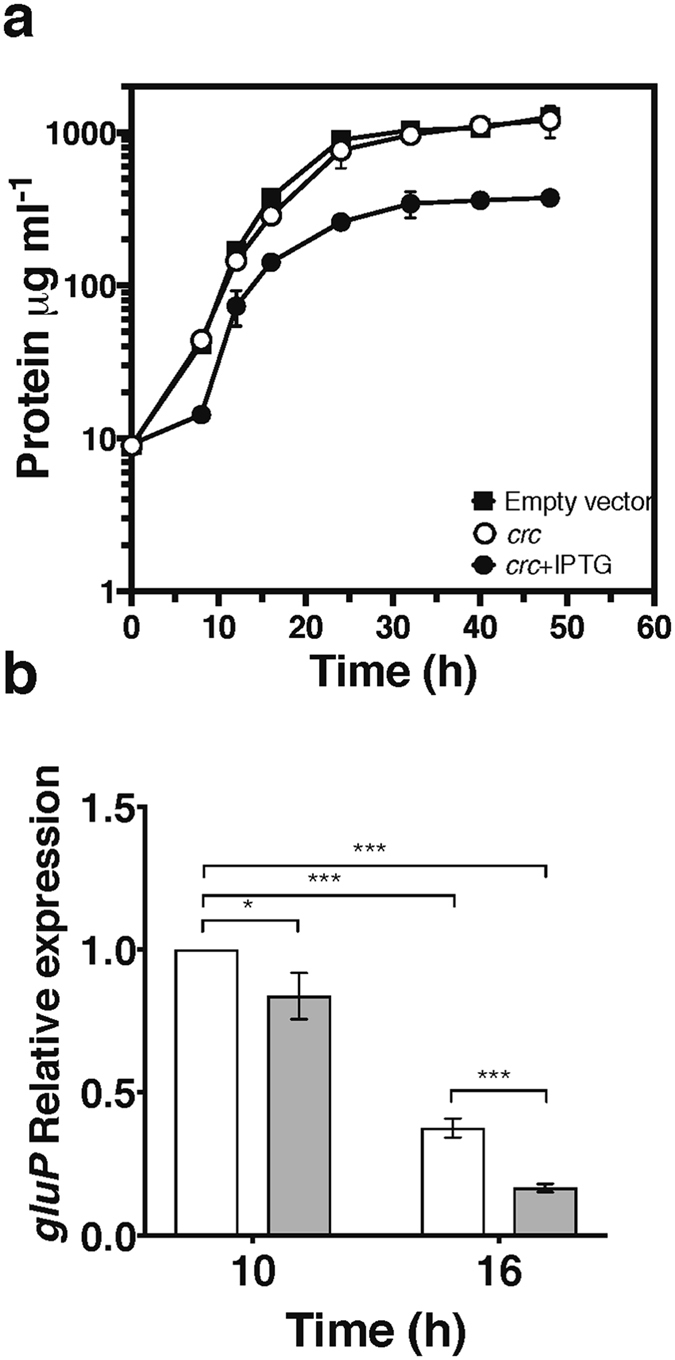

As shown above, the cbrA mutant strain AH1 was unable to use glucose in the presence of acetate. Thus, we explored the possibility that the effect of the CbrA/CbrB system on glucose assimilation was exerted through the Crc system. Efforts to construct strains carrying crc or crcZ mutations were unsuccessful. The selection of such mutants was conducted using minimal or rich medium supplemented with acetate, succinate, glucose or sucrose as carbon sources, either under diazotrophic conditions or in the presence of fixed nitrogen. This result suggested that the Crc protein and the CrcZ sRNA are necessary for the vegetative growth of A. vinelandii under laboratory conditions. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of Crc over-expression on glucose assimilation by using plasmid pSRK-crc, a pSRK-Km derivative vector carrying the A. vinelandii crc gene transcribed from a lac promoter induced only in the presence of IPTG26. For this purpose we used the wild type strain AEIV because increasing levels of Crc did not affect alginate synthesis (data not shown). Thus, pSRK-crc and the empty vector pSRK-Km were transferred to the AEIV strain, and the ability of the resulting strains to grow with glucose as the sole carbon source was evaluated. As shown in Fig. 5a, the AEIV strain carrying the empty vector exhibited normal growth and reached the stationary phase at 24 h of growth. This behaviour was similar for the AEIV strain carrying the pSRK-crc vector in the absence of IPTG. In the presence of 1 mM IPTG, however, the AEIV strain harbouring the pSRK-crc vector showed a growth lag during the first 10 h; after this time growth was resumed but started to decline at 16 h of culture reaching a maximum protein concentration of 375 µgml−1, three-fold lower than the control strain. These data indicated a negative effect of the Crc protein on glucose catabolism.

Figure 5.

Crc over-expression diminishes growth on glucose. (a) Growth kinetics of the wild type A. vinelandii AEIV strain, harbouring the empty vector pSRK-Km (■) or the pSRK-crc (crc +) vector, in the presence (●) or absence (○) of 1 mM IPTG. Cultures were developed in Burk’s minimal medium supplemented with 30 mM glucose (BG) as the sole carbon source and 1.5 µgml−1 of kanamycin as a selection marker. 25 ml of Burk’s medium supplemented with 30 mM sucrose were cultured for 18 h; cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with phosphate buffer 10 mM pH 7.2 and resuspended in the same solution. 400 µg of these cells were used to inoculate 50 ml of BG medium and samples were collected at the indicated times for protein quantification. Cell growth was estimated by determining protein concentration since the production of the exo-polysaccharide alginate by the AEIV strain prevents assessment of growth by optical density. The results represent the averages of the results of three independent experiments, and error bars depict standard deviations. (b) Relative expression levels of gluP mRNA, quantitated by qRT-PCR analysis, in cells of the wild type AEIV strain carrying the vector pSRK-crc in the absence (white colums) or presence (grey columns) of 1 mM IPTG. The growth conditions were as in panel (a). Total RNA was extracted from cells at the indicated times. The bars of standard deviation from three independent experiments are shown. Significant differences were analysed by t-test. Statistical significance is indicated (*p < 0.05 or ***p < 0.001).

When cultivated with sucrose, Crc over-expression weakly diminished cell growth at the end of the exponential phase, reaching twofold less protein concentration than the uninduced culture (Supplementary Fig. S4). This result was somewhat expected given the effect that Crc showed on glucose catabolism. In contrast, growth in the presence of preferred carbon sources such as acetate or succinate was not affected (Supplementary Fig. S4). Altogether these results imply that higher levels of Crc simulate strong CCR conditions preventing the utilization of glucose, a secondary carbon source for A. vinelandii.

GluP is the glucose transporter in A. vinelandii

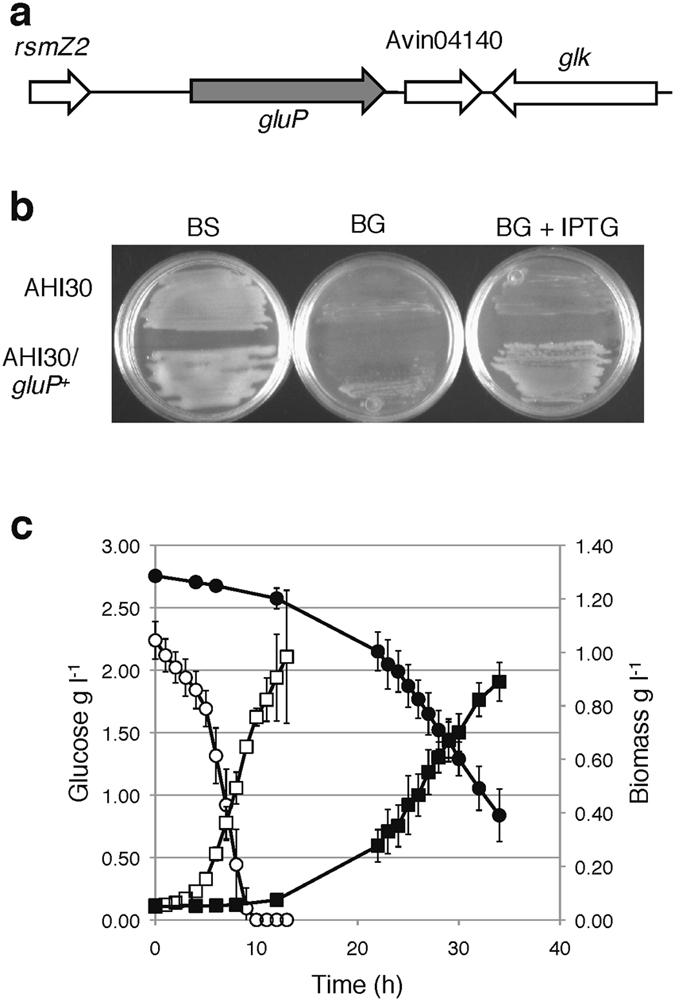

Analysis of the A. vinelandii genome allowed us to identify several genes involved in glucose metabolism and that contain putative A-rich Hfq-binding motifs near the translation start site (Supplementary Table S1). Of interest, the A. vinelandii genome lacks the typical glucose ABC transporter GtsABC present in Pseudomonas spp. but contains the gene Avin04150 (gluP), which was annotated as a transporter for glucose and galactose belonging to the Major Facilitator Superfamily of the Fucose-Galactose-Glucose:H+ symporter (FGHS) family (Fig. 6a)27, 28. The gluP gene encodes a 429 amino acid protein predicted to have 12 trans-membrane helices typical of the members of the MFS29. This protein showed 48% identity with the glucose-galactose transporter (GluP) from Brucella abortus 30. Homologues of the A. vinelandii GluP were also present in A. chroococcum and Azotobacter beijerinckii (showing 90% identity) and in a few Pseudomonas species (some of them were associated with plants).

Figure 6.

The gene gluP of A. vinelandii encodes a glucose transporter. (a) Genomic context of the A. vinelandii gluP gene. (b) Growth of the A. vinelandii glup::Sp mutant AHI30 and its derivative carrying the pSRK-gluP plasmid (gluP +) on plates of solid Burk’s medium supplemented with 2% sucrose (BS) or 50 mM glucose (BG). Where indicated, 1 mM IPTG was added to induce transcription of gluP from the lac promoter. (c) Growth kinetic, measured as cell biomass (g l−1) (squares) and glucose consumption (circles) by the E. coli WHIPC mutant (closed symbols) or its derivative carrying the pSRK-gluP (gluP +) plasmid (open symbols), in the presence of 0.1 mM IPTG. Cultures were developed in M9 mineral medium supplemented with 2.5 g l−1 of glucose.

To determine the role of GluP in glucose assimilation, strain AHI30 carrying a gluP::Sp mutation was constructed and characterized. As shown in Fig. 6b, this mutant was able to grow on sucrose; however it failed to grow on medium supplemented with glucose as the sole carbon source. Genetic complementation of AHI30 mutant with a wild type copy of gluP was conducted. To this end, gluP was cloned in the vector pSRK-Km, producing plasmid pSRK-gluP. Growth with glucose as the sole carbon source was restored for the AHI30 mutant harbouring plasmid pSRK-gluP only in the presence of 1 mM IPTG, implying that GluP is necessary for the uptake of this carbohydrate (Fig. 6b).

An additional approach was used to confirm the role of GluP as the glucose transporter in A. vinelandii. Heterologous genetic complementation of an E. coli strain devoid of the major glucose transporter systems with the A. vinelandii gluP gene was conducted. We constructed an E. coli mutant carrying multiple deletions of genes encoding the general components of the PTS system, the galactose:H+ symporter GalP and the Mgl galactose/glucose ABC transporter and named it WHIPC. Plasmids pSRK-Km (control) and pSRK-gluP were transferred to the WHIPC strain and the resulting transconjugants were tested for the ability to grow in M9 mineral medium amended with 2.5 gl−1 glucose. As shown in Fig. 6c, growth of the WHIPC mutant occurred at a specific growth rate of 0.12 h−1 and a maximum specific rate of glucose consumption of 0.01 g g of dry cell weight (DCW)−1 h−1. However, growth of the mutant WHIPC carrying the pSRK-gluP vector in M9 medium supplemented with 2.5 gl−1 glucose and 0.1 mM IPTG was clearly improved, exhibiting a specific growth rate of 0.34 h−1 and a maximum specific rate of glucose consumption of 0.1 g gDCW−1 h−1, which was ten-fold higher compared with the WHIPC strains (Fig. 6c). Several unsuccessful attempts to grow strain WHIPC harbouring the control plasmid pSRK-Km in liquid mineral M9 medium amended with glucose and kanamycin were made, which implied that the vector itself represented a genetic load that prevented cell growth. These results indicated that the A. vinelandii GluP protein functions as a glucose transporter in E. coli.

Expression of gluP is under the control of the CbrA/CbrB and Hfq-Crc systems

Because in A. vinelandii the catabolism of glucose is prevented as long as acetate is still present in the culture medium, we speculated that expression of the GluP encoding gene would be repressed under conditions of strong catabolite repression (i.e. in the presence of acetate). As expected, gluP mRNA levels, assessed by qRT-PCR analyses, were low in the presence of acetate but increased 19-times during glucose catabolism in the AEalgD strain (Fig. 2c). This response was dependent on the HK CbrA as in the cbrA mutant AH1 the levels of gluP were low throughout the growth curve with respect to the parental strain AEalgD (Fig. 2c).

We next investigated whether the growth inhibition upon Crc over-expression was associated with reduced expression of gluP. gluP mRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR at two points of the growth kinetics (6 and 10 h), corresponding to the exponential growth phase of the reference strains. Interestingly, at 10 h Crc over-expression lowered gluP mRNA levels by 20% whereas at 16 hr this effect was substantially greater as the levels of gluP were reduced by 60%, thus confirming that the Crc protein has a negative effect on the transcript abundace of gluP (Fig. 5b). Altogether these results suggested that gluP is a direct target of the Hfq-Crc proteins in the process of CCR.

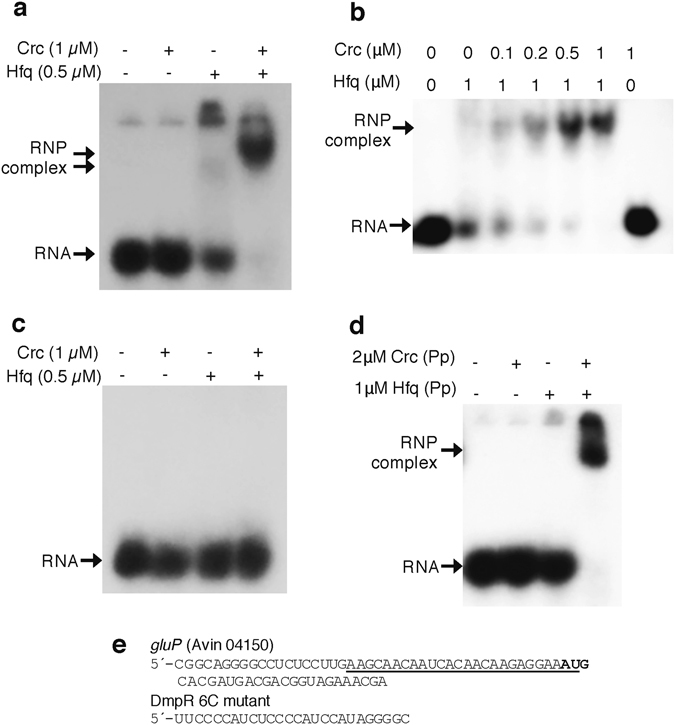

The A. vinelandii Hfq protein binds to the leader of gluP and Crc enhances this interaction

A. vinelandii Crc and Hfq-His protein preparations were used in RNA electrophoretic mobility-shift assays (EMSAs) to investigate their ability to recognize the putative A-rich Hfq-binding motif identified close to the AUG translation start codon of gluP mRNA. This analysis was achieved by using a 26 nt end-labelled RNA oligonucleotide containing the gluP A-rich Hfq-binding target. Consistent with previous reports, the A. vinelandii Crc protein alone was unable to bind to this A-rich motif (Fig. 7a), while Hfq-His could bind to the RNA oligonucleotide forming a weak complex that dissociated during electrophoresis. However, when both proteins were present, a clear ribonucleoprotein complex was formed (Fig. 7a). Based on the intensity of the shifted band, titration assays showed that efficient formation of the ribonucleoprotein complex required approximately equimolar amounts of Hfq and Crc (considering Hfq as a hexamer) (Fig. 7b). Complex formation was favoured when Hfq was in excess relative to Crc, as has been shown for alkS mRNA in P. putida 13. This stable complex was not observed with the control RNA lacking an A-rich Hfq-binding motif (Fig. 7c). Based on these results, we concluded that Crc-Hfq proteins form a complex with the gluP leader at the A-rich Hfq-binding motif.

Figure 7.

Hfq-Crc proteins form a stable ribonucleoprotein complex with the A-rich Hfq-binding RNA motif of gluP. (a) Binding of the A. vinelandii Crc and Hfq proteins to an RNA oligonucleotide containing the A-rich Hfq-binding motif present at the translation initiation region from gluP. (b) Molar ratio of the A. vinelandii Crc and Hfq proteins needed to form a ribonucleoprotein complex with the RNA containing the A-rich Hfq-binding gluP motif. As a control an RNA oligonucleotide lacking an A-rich motif was used (c). (d) Binding of the P. putida (Pp) Crc and Hfq proteins to the RNA A-rich Hfq binding motif of gluP. RNA and protein-RNA complexes were resolved in a non-denaturing polyacrilamide gel. The concentration of Crc (expressed as monomers) and Hfq (expressed as hexamers) is indicated. Arrows point to the position of free RNA and of the ribonucleoprotein complex (RNP). (e) Sequence of the gluP mRNA leader region. The underlined sequence corresponds to the RNA oligonucleotide used in the band-shift assays, which contains the A-rich motif. The AUG translation initiation codon is in bold face. The sequence of the oligonucleotide used as control in panel (c), named DmpR 6C, is also shown.

The P. putida Hfq and Crc proteins can bind to the leader of A. vinelandii gluP

Because we were unable to obtain an A. vinelandii crc mutant derivative, we analysed whether the P. putida Crc and Hfq proteins can regulate the expression of the A. vinelandii gluP gene. As a first approach, we explored whether the P. putida proteins Hfq and Crc could form a complex with the leader of gluP mRNA in vitro. Band-shift assays were conducted using purified P. putida Hfq-His and Crc proteins extracted from an Hfq-null E. coli expression strain and the 26 nt end-labelled gluP RNA oligonucleotide used in the preceding section. When applied independently, neither the P. putida Crc nor the Hfq protein could bind to the gluP A-rich Hfq-binding motif at the tested concentrations (Fig. 7d). However, when both proteins were present, a stable ribonucleoprotein complex was formed. This result implies that the P. putida Hfq and Crc proteins are able to recognize and form a complex with the A-rich motif of the gluP mRNA in vitro.

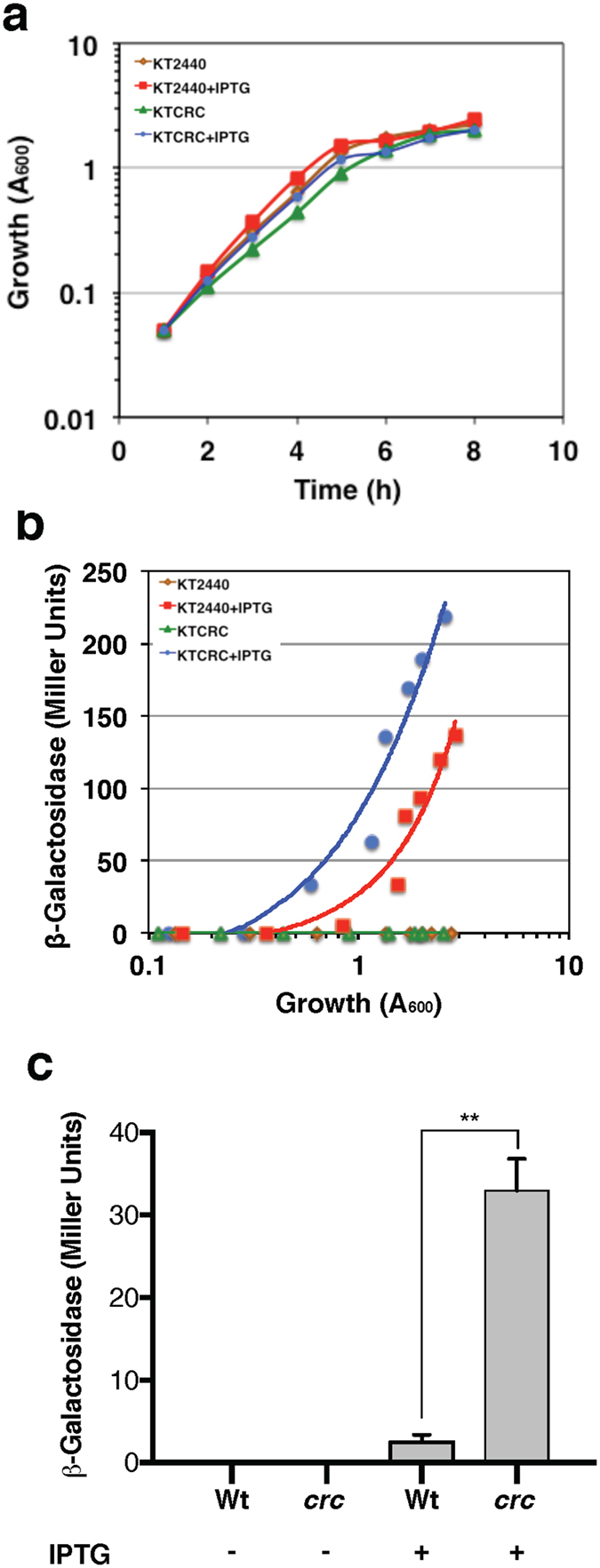

Effect of the P. putida Crc protein on the translation of gluP mRNA

To analyse the effect of the P. putida Crc protein on gluP translation, a post-transcriptional reporter fusion was constructed as previously reported31. This reporter fusion consists of a gluP’-lacZ translational fusion (60 nt of gluP relative to the ATG translation initiation site, which includes the A-rich Hfq-binding motif and the first 8 codons of gluP, fused in frame to lacZ) cloned into plasmid pSEVA424. The gluP’-lacZ sequence is transcribed from the heterologous Ptrc promoter of the vector, which can be activated by addition of IPTG. The generated plasmid, named pEQ424P, was introduced into P. putida strains KT2440 and KTCRC (a crc::tet derivative of KT2440). In cells growing in LB medium, ß-galactosidase activity was not detected when no IPTG was added to the growth medium and increased strongly in the presence of 0.5 mM IPTG (Fig. 8b). Interestingly, at the mid-exponential phase, ß-galactosidase activity in the presence of IPTG was approximately 6-fold higher in the crc genetic background than in the wild type strain (Fig. 8c). These results indicate that the Crc-Hfq proteins from P. putida recognize the gluP A-rich Hfq-binding motif reducing translation in a Crc-dependent manner.

Figure 8.

Effect of the Crc protein on the expression of a gluP’-lacZ translational fusion in P. putida. The strains used were KT2440 (wild type) and KTCRC (crc::tet) carrying plasmid pEQ424P (gluP’-lacZ). Cells were grown in LB medium and where indicated, expression of the gluP’-lacZ translational fusion was induced from the Ptrc promoter by addition of 0.5 mM IPTG. (a) Growth kinetic (measured as the turbidity at 600 nm) of each strain. (b) Activity of ß-galactosidase as a function of cell growth. (c) ß-galactosidase activity values of the gluP’-lacZ translational fusion observed at a turbidity of 0.6 (mid-exponential phase) for KT2440 or KTCRC strain. Three independent assays were performed, and a representative one is shown. Significant difference was analyzed by t-test. Statistical significance is indicated (**p < 0.01).

Discussion

One of the main characteristics of the free-living Azotobacter genus is its capacity for fixing nitrogen in aerobiosis5. In a previous study, the preference for acetate assimilation over glucose was shown in A. vinelandii cultivated under nitrogen fixing conditions8, 9. In this study, we reported the characterization of the regulatory systems CbrA/CbrB and Crc/Hfq in controlling the process of CCR, specifically the catabolic repression of glucose consumption, under diazotrophic conditions. Similar to members of the Pseudomonas genus, we found that the two-component system CbrA/CbrB is at the head of the regulatory cascade controlling CCR. Inactivation of the gene encoding CbrA diminished expression of the sRNAs CrcZ and CrcY at least 4-fold under standard laboratory conditions, i.e., minimal Burk’s medium amended with 2% sucrose (Fig. 3). Consistent with this result, putative RpoN promoters and sites recognized by the CbrA cognate RR CbrB were identified in the regulatory region of both crcZ and crcY genes. Our results revealed low expression levels of these sRNAs in the strain lacking CbrA. These results could be attributed to non-specific phosphorylation of the CbrA-cognate RR CbrB. However, the existence of alternative CbrA/CbrB-independent promoters driving crcZ and crcY expression cannot be ruled out. Putative sequences for σ70 promoters were also identified in the regulatory regions of both crcZ and crcY (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S2), but their functionality and physiological relevance need to be further investigated.

RNA EMSAs demonstrated that CrcZ from A. vinelandii formed a stable ribonucleoprotein complex with A. vinelandii proteins Hfq and Crc, as has been shown in P. putida 13. Hfq was capable of recognizing the CrcZ A-rich Hfq-binding motifs, but the presence of Crc changed the electrophoretic mobility of the shifted band and enhanced the stability of the complex (Fig. 4b and c). This result implies that the sRNA CrcZ (and possibly CrcY) antagonizes the repressing activity of Hfq and Crc and prevents them from controlling their target genes, as it has been proposed to occur in several Pseudomonas species. The HK CbrA was necessary for the assimilation of glucose either as the sole carbon source or when mixed with acetate (Fig. 2). This result was attributed to low expression levels of the CrcZ and CrcY sRNAs in the cbrA genetic background that in turn allowed the Hfq-Crc repressing activity. Indeed, we found that over-expression of the A. vinelandii Crc protein from an inducible promoter in the wild type strain AEIV arrested cell growth at the mid-log phase when the strain was cultured in the presence of glucose (Fig. 5a). This result further indicates the ability of Crc to repress glucose assimilation.

We found that A. vinelandii imports glucose using a GluP transporter, a protein that is absent in most Pseudomonas spp. GluP was essential for glucose consumption in A. vinelandii, whilst expression of gluP in an E. coli mutant (with inactivated or deleted genes encoding the major glucose transporters) restored the mutant’s ability to grow in the presence of glucose (Fig. 6c). Similarly, the GluP homologue from B. abortus, a glucose and galactose transporter, was functional in E. coli 30. A. vinelandii GluP belongs to the FGHS family of H+-coupled symporters. This finding is consistent with an early report describing active transport of D-glucose by membrane vesicles prepared from A. vinelandii cells7. The transport of glucose was coupled to the oxidation of L-malate and was induced by growth of the cells on D-glucose but arrested in cells grown on acetate. The presence of GluP in A. vinelandii, rather than the GtsABC sugar ABC transporter commonly found in Pseudomonas species, might be due to the intrinsic physiological and metabolic characteristics of this bacterium. A global comparison of transport capabilities among several bacterial species suggested that the preponderance of proton motive force-driven transporters, versus ATP-driven permeases, seems to be explained by the type of energy source most readily generated by the organism32. A. vinelandii exhibits a high respiratory rate which is needed to protect the nitrogenase enzyme from inactivation by oxygen during aerobic nitrogen fixation, a process that has not been reported in Pseudomonas species1, 2. Therefore, the proton motive force generated by the highly active respiratory electron-transport chain in A. vinelandii can explain the presence of the GluP H+-dependent symporter.

Although the Hfq-Crc system in Pseudomonas spp. is known to exert a posttranscriptional effect it has been reported that the transcript abundance of target genes could be also altered, presumably reflecting the effects of translational control on mRNA stability20. Interestingly, gluP mRNA levels were reduced in the presence of acetate and increased 19-fold during glucose assimilation. Moreover, the gluP mRNA levels were reduced by Crc over-expression or in the absence of the HK CbrA, suggesting that gluP could be one of the Crc-Hfq targets during CCR control. Indeed, we found that Crc and Hfq proteins from either A. vinelandii or P. putida cooperated to form a stable ribonucleoprotein complex with the gluP RNA A-rich Hfq-binding motif (Fig. 7a and d). Moreover, the presence of the gluP A-rich Hfq-binding motif at the leader region of the lacZ reporter gene inhibited translation in P. putida in a Crc-dependent manner. These results imply that the Crc-Hfq proteins from A. vinelandii and P. putida are functionally interchangeable which is further reinforced by the fact that these two proteins are highly conserved in these organisms (Supplementary Fig. S5).

The A. vinelandii eda-1 gene, encoding a KDPG-aldolase enzyme of the ED pathway for glucose assimilation, is predicted to have an A-rich Hfq-binding motif (Supplementary Table S1). EMSAs showed that the Crc-Hfq proteins from either A. vinelandii or P. putida could recognize this motif (Supplementary Fig. S6), implying that the eda-1 gene is a target of these proteins. The genome of A. vinelandii has been shown to be abundant in highly similar homologues among carbohydrate metabolism genes33. The eda-1paralogue eda-2 (Avin15720) shares 81% identity with eda-1 but it lacks apparent A-rich Hfq-binding motifs. Taken together these results suggest that glucose uptake may constitute a key step during the CCR process for this carbohydrate in A. vinelandii. However, other genes involved in the assimilation of glucose are also controlled by Crc/Hfq, a multi-tier strategy that has also been observed in P. putida 34.

The cbrA::miniTn5 mutant was able to utilise sucrose as the sole carbon source. Growth in this carbon source, however, was compromised as the cbrA::miniTn5 mutant reached three-fold less biomass than the parental strain (Fig. 2a). Given the reiteration of genes for the metabolism of glucose explained above, we speculated that the uptake of this disaccharide might be subjected to CCR control. In agreement with this idea a putative A-rich Hfq-binding motif (AAAAACAA) at the leader region of lacY (Avin51800; encoding the sucrose permease) was identified. Since growth on sucrose was allowed in the absence of cbrA or upon Crc sobre-expression, two conditions that clearly inhibited growth on glucose, it is likely that lacY is not subjected to a strong CCR control, as is the case for the glucose transporter GluP.

In conclusion, in this study we presented evidence indicating that glucose transport in A. vinelandii occurs through a GluP transporter, rather than through the GtsABC sugar transporter present in most Pseudomonas spp. However, we found that gluP expression is under the control of the CbrA/CbrB and Crc/Hfq systems, as it occurs with the gtsABC genes in Pseudomonas spp.21, 35, 36. In fact, we showed that during diazotrophic growth the A. vinelandii CbrA/CbrB and Crc/Hfq systems operate in a similar manner and they are functionally conserved with respect to P. putida and other Pseudomonas species in regulating the CCR process. This finding reinforces the importance of these regulatory systems in the metabolism of members of the Pseudomonadaceae family.

Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Bacterial strains, plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Tables S2, S3 and S4, respectively. A. vinelandii was grown in minimal Burk’s -sucrose medium as previously reported37. E. coli DH5α38 and EC6779 strains12 were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37 °C39. The WHIPC strain was grown in Mineral M9 medium supplemented with 2.5 gl−1 of glucose. P. putida wild type strain KT244040 and its derivative KTCRC were grown in LB as previously reported34. When needed, the final antibiotic concentrations (in µgml−1) used for A. vinelandii and E. coli were as follows: kanamycin (Km) 1.5 and 10; spectinomycin (Sp), 100 and 100; tetracycline (Tc) 10 and 10. A. vinelandii transformation was carried out as previously described41. The Supplementary Methods summarize general nucleic acid procedures.

Construction of plasmids pSRK-crc and pSRK-gluP

crc ORF flanked with SacI and HindIII restriction sites was PCR amplified using primers SPcrc-F (SacI) and crc-R (HindIII). This fragment (1053 bp) was ligated into corresponding sites of pSRKKm26, generating pSRK-crc. gluP ORF was PCR amplified with primers gluP-F and gluP-R and was cloned into vector pJET 1.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which produced plasmid pAH01. A 1.9 kb BglII-XhoI DNA fragment containing gluP was released from pAH01 and was cloned into the corresponding sites of vector pSRKKm, which produced plasmid pSRK-gluP. Plasmids derived from pSRKKm were used to express the cloned gene from an isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) inducible lac promoter.

Construction of plasmid pEQ424P

To generate a translational fusion of the gluP leader region with lacZ, an EcoRI-BamHI fragment of 670 bp (−630 to +28 nt of the gluP gene) was PCR amplified using primers gluPF-EcoR1 and gluPR-Bam and was cloned between the corresponding sites of plasmid pUJ942. pUJ9 contains a promoterless lacZ gene, and generates plasmid pUJEQP. A post-transcriptional reporter fusion (Ptrc-gluP’-lacZ) was constructed in plasmid pSEVA42443, in which the gluP’-lacZ translational fusion could be transcribed from the Ptrc promoter of the vector upon addition of IPTG. To this end, the gluP’-lacZ was PCR-amplified with primers LgluP-FwEcoRI and LacZ-RevHindIII containing restriction sites for EcoRI and HindIII, respectively, and using plasmid pUJEQP as a template. The amplified fragment was EcoRI-HindIII double digested and cloned into the corresponding restriction sites of plasmid pSEVA424, producing plasmid pEQ424P. The correct construction was verified by DNA sequencing. Plasmid pEQ424P was introduced by electroporation into P. putida wild type strain KT244040 and its derivative KTCRC that carries an inactivated crc::tet allele34.

Generation of mutant GG15 (cbrA::miniTn5)

Construction of a random miniTn5 mutant bank derived from strain AEIV with the miniTn5SSgusA40 (Spr) transposon44 was previously reported45. Mutant GG15 was identified in this mutant bank due to its highly mucoid phenotype on plates of Burk’s-sucrose medium. The miniTn5 lacks PstI restriction sites. Therefore, the chromosomal region interrupted by the miniTn5 was cloned as a PstI fragment into vector pBluescript KS + (Stratagene), producing plasmid pGG15. Nucleotide sequencing across the transposon insertion junction, using primers Tn5O and Tn5I45 and plasmid pGG15 as DNA template was conducted and showed that the cbrA gene was disrupted in mutant GG15.

Construction of A. vinelandii mutants

A. vinelandii was transformed with linear DNA carrying the desired mutation to ensure double reciprocal recombination and allelic exchange. Transformants were selected on Burk’s-sucrose medium amended with the corresponding antibiotic. Gene inactivation was confirmed by PCR analysis. For mutant AEalgD, AEIV cells were transformed with plasmid pJGD (algD::Km) linearized with PstI. The resulting Kmr mutant was named AEalgD, and the corresponding gene inactivation was confirmed by PCR analysis using oligonucleotides algDF and algDR. For mutant AH1, competent A. vinelandii cells of mutant AEalgD were transformed with plasmid pGG15 (cbrA::miniTn5). Transformants Spr were selected, and the presence of the cbrA::miniTn5 mutation and the absence of wild type copies of cbrA were verified by PCR amplification using oligonucleotides F-1(cbrA) and R-1(cbrA). For the construction of mutant EQR02 (cbrA::Sp), plasmid pJGEY2 (cbrA::Sp) was linearized with EcoRI and was used to transform A. vinelandii AEIV cells, and double recombinants Spr were selected. The resulting cbrA::Sp mutant was named EQR02. PCR amplification of the cbrA locus with oligonucleotides F-1(cbrA) and R-1(cbrA), confirmed the presence of the cbrA::Sp mutation and the absence of wild type copies of the cbrA gene. Mutant AHI30 (gluP::Sp) was constructed by transforming wild type AEIV cells with plasmid pAH03, previously linearized with XhoI, and transformants resistant to Sp were selected. The presence of the gluP::Sp mutation and the absence of wild type gluP alleles were confirmed by PCR amplification patterns using primer pairs gluP-F and gluP-R. Construction of plasmids pJGD, pJGEY2 and pAH03 is detailed in the Supplementary Methods.

Construction of chromosomal PcrcZ-gusA and PcrcY-gusA transcriptional fusions

For the construction of strains carrying PcrcZ-gusA transcriptional fusions, plasmid pEY05 was generated. This plasmid carries a PcrcZ-gusA transcriptional fusion that can be integrated into the scrX locus in the A. vinelandii chromosome. Construction of plasmid pEY05 is described in the Supplementary Methods. Competent A. vinelandii cells of strains AEIV and EQR02 (cbrA::Sp) were transformed with plasmid pEY05 (PcrcZ-gusA, Tcr) previously linearized with enzyme NdeI. AEIV and EQR02 Tcr derivatives were iso lated and confirmed, by PCR amplification patterns to carry the PcrcZ-gusA construction; the resulting strains were named AE-Zgus and CbrA-Zgus, respectively. For the construction of strains carrying PcrcY-gusA transcriptional fusions plasmid pGJ112 was generated. This plasmid is derived from plasmid pUMATcgusAT46 and carries the regulatory region of crcZ directing transcription of the gusA reporter gene to be integrated into the melA locus. Construction of plasmid pGJ112 is described in the Supplementary Methods. Competent A. vinelandii cells from strains AEIV and EQR02 (cbrA::Sp) were transformed with plasmid pGJ112 (Tcr) previously linearized with enzyme NdeI. AEIV and EQR02 derivatives Tcr were isolated and confirmed, by PCR amplification patterns to carry the PcrcY-gusA construction; the resulting strains were named AE-Ygus and Cbr-Ygus, respectively.

Construction of the E. coli mutant WHIPC

Mutant WHIPC carries mutations in genes encoding the major glucose transporter systems (∆ptsHIcrr, ∆mglABC::FRT-Cm-FRT, galP::FRT) and was constructed from mutant WHIP47 which lacks the galactose:H+ symporter GalP transporter and genes encoding the general components of the phosphoenol pyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase (Pts) system (galP::FRT; ∆ptsHIcrr). The mglABC operon was inactivated in mutant WHIP as previously described48, employing PCR products amplified with primers mglABCDtF and mglABCDtR and plasmid pKD3 as the DNA template47. Verification of the chromosomal mglABC deletion in mutant WHIPC was accomplished by PCR using primers mglABF and mglABR as previously reported47.

Quantitative real time reverse transcription (qRT-PCR)

A. vinelandii strains were cultured in Burk’s minimal medium supplemented with the indicated carbon source. Details of total RNA extraction, the primers design, cDNA synthesis and qRT-PCR amplification conditions are reported in the Supplementary Methods. The sequences of the primer pairs used for the genes gluP (gluP qPCR Fw and gluP qPCR Rv) and 16 s (16 S Fw and 16 S Rv) are listed in Table S4. As in previous studies49, 16 s rRNA (Avin55110) was used as internal control in the same sample to normalize the results obtained, as its expression was constant under the tested conditions. The quantification technique used to analyze the generated data was the 2-∆,∆CT method reported previously50.

RNA band-shift assays

A. vinelandii Crc and Hfq-His proteins were expressed and purified as described in the Supplementary Methods. RNA oligonucleotides containing the A-rich Hfq-binding motifs of gluP and eda1, were synthesized by Sigma, labelled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]-ATP and purified through MicroSpin G-25 columns (GE Healthcare). Their sequences are as follows: gluP, 5′-AAGCAACAAUCACAACAAGAGGAAAU; eda-1, 5′-CAUCCAGAACAACAAACCGGCCACUU. CrcZ sRNA was obtained by in vitro transcription. To this end, crcZ gene flanked with HindIII and EcoRI restriction sites was obtained by PCR using primer pairs crcZHd-Fw and crcZEco-ROK and was ligated into the corresponding sites of pTZ19r (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which generated pEQZIT. The insert was sequenced to ensure that it contained the desired DNA fragment. Radioactively labelled CrcZ was obtained as previously described25. EMSAs were conducted as described13.

Analytical methods

Protein levels were determined as previously reported51. β-Glucuronidase activity was determined as previously described52. One U corresponds to 1 nmol of o-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucuronide hydrolysed per min per µg of protein. The β-galactosidase activity of P. putida cells was determined as follows: an overnight culture of P. putida was diluted to a final turbidity (A600) of 0.05 in fresh LB medium. Where indicated, 0.5 mM IPTG was added to induce transcription from promoter Ptrc. Cells were allowed to grow at 30 °C with vigorous aeration, and aliquots were taken at different time points. β-galactosidase activity was measured as previously described39 using o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactoside as the substrate. Glucose and acetate quantification were performed by HPLC using an Aminex HPX-87H column (300 9 7.8 mm) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The eluent used was H2SO4 (7 mM) at a flow rate of 0.8 mlmin−1. Glucose and acetate detection were achieved using a refractive index (RI) detector (Waters 2414 detector). All experiments were conducted at least three times, and the results presented are the averages of independent runs. When required, the Figures show the mean values and standard deviations among biological replicates.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 7.0) software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test, and a p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Ocádiz, J. M. Hurtado, D.S. Castañeda and S. Becerra for computational support and for oligonucleotides synthesis. We are grateful to G. Gosset for providing E. coli strain WHIP and to B.E. Uhlin for providing the E. coli MG1655 Hfq-null strain. This work was supported by grants from Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica, UNAM (PAPIIT IN208514) and from the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT CB-240095 and INFR 253487) to Cinthia Núñez, and grants BFU2012-32797 (MINECO, Spain), and BIO2015-66203-P (MINECO/FEDER) to Fernando Rojo. EQR was recipient of a scholarship from CONACyT.

Author Contributions

C.N. and F.R. conceived the project; E.Q.R., R.M., A.H.O., J.C.F.J., L.F.M.M. and J.G. performed experiments; C.N., E.Q.R., G.E. and F.R. wrote the manuscript. E.Q.R., R.M., J.C.F.J., L.F.M.M., G.E., F.R. and C.N. discussed and reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00980-5

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kennedy, C., Rudnick, P., MacDonald, T. & Melton, T. Genus Azotobacter.In G. M. Garrita (ed), Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology, Springer-Verlag, New York, NY vol. 2, part B, 384–401 (2005).

- 2.Setubal JC, et al. Genome sequence of Azotobacter vinelandii, an obligate aerobe specialized to support diverse anaerobic metabolic processes. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:4534–4545. doi: 10.1128/JB.00504-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segura D, Núñez C, Espín G. Azotobacter cysts. eLS Wiley Online Library. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galindo E, Peña C, Núñez C, Segura D, Espín G. Molecular and bioengineering strategies to improve alginate and polydydroxyalkanoate production by Azotobacter vinelandii. Microb Cell Fact. 2007;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy C, et al. The nifH, nifM and nifN genes of Azotobacter vinelandii: characterization by Tn5 mutagenesis and isolation from pLARF1 gene banks. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1986;205:318–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00430445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conway T. The Entner-Doudoroff pathway: history, physiology and molecular biology. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;9:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes EM., Jr. Glucose transport in membrane vesicles from Azotobacter vinelandii. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1974;163:416–422. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(74)90493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George SE, Costenbader CJ, Melton T. Diauxic growth in Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:866–871. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.866-871.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tauchert K, Jahn A, Oelze J. Control of diauxic growth of Azotobacter vinelandii on acetate and glucose. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6447–6451. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6447-6451.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rojo F. Carbon catabolite repression in Pseudomonas : optimizing metabolic versatility and interactions with the environment. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34:658–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filiatrault MJ, et al. CrcZ and CrcX regulate carbon source utilization in Pseudomonas syringae pathovar tomato strain DC3000. RNA Biol. 2013;10:245–255. doi: 10.4161/rna.23019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madhushani A, Del Peso-Santos T, Moreno R, Rojo F, Shingler V. Transcriptional and translational control through the 5′-leader region of the dmpR master regulatory gene of phenol metabolism. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:119–133. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreno R, et al. The Crc and Hfq proteins of Pseudomonas putida cooperate in catabolite repression and formation of ribonucleic acid complexes with specific target motifs. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:105–118. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonnleitner E, Abdou L, Haas D. Small RNA as global regulator of carbon catabolite repression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21866–21871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910308106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Mauriño SM, Pérez-Martínez I, Amador CI, Canosa I, Santero E. Transcriptional activation of the CrcZ and CrcY regulatory RNAs by the CbrB response regulator in Pseudomonas putida. Mol Microbiol. 2013;89:189–205. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreno R, Marzi S, Romby P, Rojo F. The Crc global regulator binds to an unpaired A-rich motif at the Pseudomonas putida alkS mRNA coding sequence and inhibits translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:7678–7690. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno R, Rojo F. The target for the Pseudomonas putida Crc global regulator in the benzoate degradation pathway is the BenR transcriptional regulator. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1539–1545. doi: 10.1128/JB.01604-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moreno R, Ruiz-Manzano A, Yuste L, Rojo F. The Pseudomonas putida Crc global regulator is an RNA binding protein that inhibits translation of the AlkS transcriptional regulator. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:665–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuste L, Rojo F. Role of the crc gene in catabolic repression of the Pseudomonas putida GPo1 alkane degradation pathway. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6197–6206. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6197-6206.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonnleitner E, Blasi U. Regulation of Hfq by the RNA CrcZ in Pseudomonas aeruginosa carbon catabolite repression. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno R, Martínez-Gomariz M, Yuste L, Gil C, Rojo F. The Pseudomonas putida Crc global regulator controls the hierarchical assimilation of amino acids in a complete medium: evidence from proteomic and genomic analyses. Proteomics. 2009;9:2910–2928. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li W, Lu CD. Regulation of carbon and nitrogen utilization by CbrAB and NtrBC two-component systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:5413–5420. doi: 10.1128/JB.00432-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quiroz-Rocha, E. et al. The two-component system CbrA/CbrB controls alginate production in Azotobacter vinelandii. Microbiology. In press (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Hay ID, Ur Rehman Z, Moradali MF, Wang Y, Rehm BH. Microbial alginate production, modification and its applications. Microb Biotechnol. 2013;6:637–650. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreno R, Fonseca P, Rojo F. Two small RNAs, CrcY and CrcZ, act in concert to sequester the Crc global regulator in Pseudomonas putida, modulating catabolite repression. Mol Microbiol. 2012;83:24–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan SR, Gaines J, Roop RM, 2nd, Farrand SK. Broad-host-range expression vectors with tightly regulated promoters and their use to examine the influence of TraR and TraM expression on Ti plasmid quorum sensing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5053–5062. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01098-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pao SS, Paulsen IT, Saier MH., Jr. Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1–34. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.1-34.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saier MH, Jr., et al. The major facilitator superfamily. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;1:257–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saier MH., Jr. Tracing pathways of transport protein evolution. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1145–1156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Essenberg, R. C., Candler, C. & Nida, S. K. Brucella abortus strain 2308 putative glucose and galactose transporter gene: cloning and characterization. Microbiology143 (Pt 5), 1549–1555, doi:10.1099/00221287-143-5-1549 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Pannuri A, et al. Translational repression of NhaR, a novel pathway for multi-tier regulation of biofilm circuitry by CsrA. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:79–89. doi: 10.1128/JB.06209-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paulsen IT, Sliwinski MK, Saier MH., Jr. Microbial genome analyses: global comparisons of transport capabilities based on phylogenies, bioenergetics and substrate specificities. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:573–592. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mærk M, Johansen J, Ertesvåg H, Drabøs F, Valla S. Safety in numbers: multiple occurrences of highly similar homologs among Azotobacter vinelandii carbohydrate metabolism proteins probably confer adaptive benefits. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:192. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hernández-Arranz S, Moreno R, Rojo F. The translational repressor Crc controls the Pseudomonas putida benzoate and alkane catabolic pathways using a multi-tier regulation strategy. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:227–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.del Castillo T, Ramos JL. Simultaneous catabolite repression between glucose and toluene metabolism in Pseudomonas putida is channeled through different signaling pathways. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6602–6610. doi: 10.1128/JB.00679-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.La Rosa R, Nogales J, Rojo F. The Crc/CrcZ-CrcY global regulatory system helps the integration of gluconeogenic and glycolytic metabolism in Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:3362–3378. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Núñez C, et al. Alginate synthesis in Azotobacter vinelandii is increased by reducing the intracellular production of ubiquinone. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:2503–2512. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller, J. H. Experiments in Molecular Genetics., (Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory., 1972).

- 40.Franklin FC, Bagdasarian M, Bagdasarian MM, Timmis KN. Molecular and functional analysis of the TOL plasmid pWWO from Pseudomonas putida and cloning of genes for the entire regulated aromatic ring meta cleavage pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7458–7462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahumada-Manuel CL, et al. The signaling protein MucG negatively affects the production and the molecular mass of alginate in Azotobacter vinelandii. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;101:1521–1534. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7931-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis KN. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silva-Rocha R, et al. The Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA): a coherent platform for the analysis and deployment of complex prokaryotic phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D666–675. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson, K. J. et al. beta-Glucuronidase (GUS) transposons for ecological and genetic studies of rhizobia and other gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology141 (Pt 7), 1691–1705, doi:10.1099/13500872-141-7-1691 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Núñez C, et al. The Na + -translocating NADH : ubiquinone oxidoreductase of Azotobacter vinelandii negatively regulates alginate synthesis. Microbiology. 2009;155:249–256. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.022533-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muriel-Millán LF, et al. The unphosphorylated EIIA(Ntr) protein represses the synthesis of alkylresorcinols in Azotobacter vinelandii. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fuentes LG, et al. Modification of glucose import capacity in Escherichia coli: physiologic consequences and utility for improving DNA vaccine production. Microb Cell Fact. 2013;12:42. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hernández-Eligio A, et al. RsmA post-transcriptionally controls PhbR expression and polyhydroxybutyrate biosynthesis in Azotobacter vinelandii. Microbiology. 2012;158:1953–1963. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.059329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson KJ, et al. beta-Glucuronidase (GUS) transposons for ecological and genetic studies of rhizobia and other gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology. 1995;141:1691–1705. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-7-1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.