Abstract

Objectives

To examine the relationship of negative emotions with suicidal ideation during 12-weeks of Problem Adaptation Therapy (PATH) vs. Supportive Therapy of Cognitively Impaired Older Adults (ST-CI). We hypothesize that: a) improved negative emotions are associated with reduced suicidal ideation; b) PATH improves negative emotions more than ST-CI; and c) improved negative emotions, rather than other depression symptoms, predict reduction in suicidal ideation.

Design

RCT of two home-delivered psychosocial interventions.

Setting

Weill-Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry; interventions and assessments were conducted at participants’ home.

Participants

74 older participants (65–95 years old) with MDD and cognitive impairment were recruited in collaboration with community agencies. The sample reported less intense feelings than suicidal intention.

Interventions

PATH focuses on improving emotion regulation whereas ST-CI focuses on non-specific therapeutic factors, such as understanding and empathy.

Measurements

Improved negative emotions are measured as improvement in Montgomery Asberg’s Depression Rating Scales’ (MADRS) observer-ratings of sadness, anxiety, guilt, hopelessness and anhedonia. Suicidal ideation was assessed with the MADRS Suicide Item.

Results

MADRS Negative Emotions scores were significantly associated with suicidal ideation during the course of treatment (F[1, 165]=12.73, p=0.0005). PATH participants had significantly greater improvement in MADRS emotions than ST-CI participants (treatment group by time: F[1,63.2]=7.02, p=0.0102). Finally, improved negative emotions, between lagged and follow-up interview, significantly predicted reduction in suicidal ideation at follow-up interview (F[1, 96]=9.95, p=0.0022).

Conclusions

Our findings that improvement in negative emotions mediates reduction in suicidal ideation may guide the development of psychosocial interventions for reduction of suicidal ideation.

Keywords: Emotions, Suicidal ideation, suicide, depression, cognitive impairment, psychosocial treatment, emotional states

INTRODUCTION

Suicide rates in older adults are alarmingly high. The suicide rate of older adults (≥65 years old) in the US have increased gradually from 2006–2014, reaching 16.6/100,000 in 2014[1]. The highest risk group for suicide continues to be white males 85 years of age or older (Suicide rate in 2014: 54.4 per 100,000)[1].

Major depression, cognitive impairment and suicidal ideation are risk factors for suicide in older adults. Major depression is the most common diagnosis in postmortem studies of suicide deaths[2,3]. Cognitive impairment, especially executive dysfunction and poor cognitive control[4], and early diagnosis of a dementing disorder contribute to increased suicide risk in the elderly[5]. Suicidal ideation is a consistent predictor of suicide attempts and completed suicides in the elderly, non-suicide mortality, and compromised quality of life for patients and their families[2,6]. Reducing modifiable suicide risk factor, such as suicidal ideation, is an NIMH high research priority7.

Improving the emotional states associated with depression is one promising target to reduce suicidal ideation in older adults with major depression and cognitive impairment. Depressed, older adults experience high levels of sadness, anxiety, hopelessness, helplessness, and guilt, all of which could precipitate suicidal ideation and behavior[8–12]. Improvement in emotional states contributes to decreased suicidal ideation and suicide risk in different populations, including older adults[6,11–17]. Brain dysfunction leading to executive, memory and attention deficits, may impair emotion regulation[17,18,19,20]. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to explore the relationship of improved emotions with suicidal ideation during psychosocial treatments of older, depressed, cognitively impaired patients.

Our study focuses on two home-delivered psychosocial treatments, Problem Adaptation Therapy (PATH) and Supportive Therapy for Cognitively Impaired Older Adults (ST-CI). Whereas ST-CI targets non-specific therapeutic factors such as providing a supportive environment, fostering empathy, and emphasizing positive experiences, PATH focuses specifically on improving emotion regulation. To accomplish this goal, PATH utilizes a problem solving approach, environmental adaptations and compensatory strategies to remedy the patients’ cognitive, behavioral and functional limitations, and selectively engages caregiver to participate in treatment. In depressed, cognitively impaired and disabled older adults, PATH leads to greater reduction of depression and disability than home-delivered ST-CI over 12 weeks[21].

The present study examines the relationship of negative emotions, associated with depression, with suicidal ideation during 12-weeks of PATH vs. ST-CI. Improvement in negative emotions is measured as improvement in observer-ratings of sadness, anxiety, guilt, hopelessness and anhedonia. We hypothesize that over 12 weeks of treatment: a) improved negative emotions are associated with reduced suicidal ideation; b) PATH will improve negative depressive emotions more than ST-CI; and c) improved negative emotions, rather than other depression symptoms, predict reduction in suicidal ideation.

METHODS

Participants

Seventy four older adults with major depression, cognitive impairment (up to the level of moderate dementia), and disability participated in an RCT that compared the efficacy of PATH vs. ST-CI. Participants were recruited through collaborating community agencies of the Weill Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry, located at a University Hospital in Westchester County, NY. Study procedures were approved by the institutional review board. The CONSORT diagram of the RCT, participants’ baseline clinical and demographic information, and results on primary outcomes of depression and disability have been reported in a separate article[21]. In that article, PATH participants had greater reduction in depression and disability than ST-CI participants over 12 weeks. The present article focuses on the relationship of negative emotions associated with depression and suicidal ideation.

Eligible participants were 65 years old or older and had a diagnosis of unipolar non-psychotic MDD by DSM-IV criteria, a Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)[22] total score ≥17, cognitive impairment (at least mild cognitive deficits (age-adjusted and education-adjusted scaled score of ≤7 on the Dementia Rating Scale [DRS] subscale of memory or initiation perseveration) and disability (at least one impairment in activities of daily living). Participants were not taking psychotropic drugs, including antidepressants, cholinesterase inhibitors, or memantine, or were taking a stable dosage for at least 6 weeks prior to entry with no medical recommendation for medication change in the next 3 months. Exclusion criteria included: (1) presence of any active comorbid Axis I psychiatric disorder (except anxiety disorders); (2) presence of acute or severe medical illness during the three months prior to entry; or prescription of drugs known to cause depression; (3) current involvement in psychotherapy; (4) severe cognitive impairment [Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)[23] score < 17]; (5) presence of active suicidal ideation with intent or plan; and (6) aphasia and inability to speak English.

Procedures in the study comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Potential participants with capacity to consent (assessed with Cornell Scale for Capacity to Consent) signed consent forms and were randomly assigned to home-delivered PATH or home-delivered ST-CI. Research assistants were unaware of participants’ randomization status and the study hypotheses.

Assessment and Instruments

We assessed suicidal ideation at entry (baseline), week 4, week 8, and week 12 with Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale[22] – Suicide Item (MADRS-SI), rated on a scale of 0–6 ranging from 0=No suicidal ideation to 6=Explicit plans for suicide; active preparations for suicide. MADRS ratings were evaluated using our MADRS administration guide for older adults[24]. According to these ratings, MADRS-SI scores corresponded to the following anchor points: 0=No suicidal ideation; 1=life is not worth living; 2=passive suicidal thoughts/death wishes; 3=uncommon active suicidal thoughts; suicide is not an option; 4=suicidal thoughts are common; active suicidal ideation without intent or plan; 5=active suicidal ideation with intent or plan; and 6=Explicit plans for suicide; active preparations for suicide. Participants with active suicide thoughts with intent or plan (MADRS-SI≥5) were excluded from the study and were either referred for more intense outpatient psychiatric treatment. Because of the skewed distribution of the MADRS Suicide item, we created a binary variable (Suicidal ideation vs. No Suicidal ideation at any timepoint: i.e. any participants with MADRS Suicide ≥1 were in the Suicidal ideation group for that timepoint). Depression and disability were quantified at all assessments (entry, week 4, week 8, and week 12) by the MADRS total score and the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHODAS II)-12 item form[25]. We calculated depression severity excluding the suicide item by subtracting the MADRS-SI item from MADRS total (MADRS minus SI). Overall cognitive impairment at baseline was assessed with the DRS total[26].

We summed the 5 MADRS items that capture negative emotional states, namely, sadness (MADRS 1 & MADRS 2), anxiety and worry (MADRS 3), anhedonia/lack of pleasure or interest in activities (MADRS 8), and feelings of guilt, self-reproach, and hopelessness (MADRS 9). We refer to this sum as MADRS Negative Emotions. To examine the specificity of the relationship of MADRS Negative Emotions with suicidal ideation, we also examined the influence of the MADRS Cognitive (MADRS 6: Concentration Difficulties), Energy (MADRS 7: Lassitude), and Vegetative items (MADRS 4 & 5: Reduced Sleep & Appetite) and the rest of MADRS items (i.e., MADRS total minus the MADRS Negative Emotions and minus the MADRS Suicidal Ideation item).

Therapists were doctoral-level clinical psychologists, clinical social workers and a doctoral candidate in a clinical psychology program and were trained in both PATH and ST-CI. Therapists’ treatment fidelity scores were very good to excellent[21].

Interventions

Problem Adaptation Therapy (PATH)

PATH is a home-delivered psychosocial intervention, administered in 12 weekly sessions, designed to help older adults with major depression, cognitive impairment (up to the level of moderate dementia), and disability. PATH follows the process model of emotion regulation[27], and utilizes individually-tailored strategies to reduce negative and promote positive emotions such as: situation selection (selecting the situations a person is exposed to), situation modification (changing potentially emotion-eliciting situations), attentional deployment (shifting one’s attention within a situation), cognitive change (changing how one thinks about a situation), or response modulation (utilizing direct efforts to alter one’s emotional responses). It integrates PATH tools (environmental adaptations and compensatory strategies, e.g. calendar, checklists, strategies to sustain or shift attention, step-by-step division of a task) to compensate for the patient’s behavioral and functional limitations and reduce their emotional impact. PATH also invites an available and willing caregiver to participate in treatment to help patient improve emotion regulation.

Supportive Therapy for Cognitive Impaired Older Adults (ST-CI)

ST-CI is also a home-delivered psychotherapy, administered in 12 weekly sessions. ST-CI is based on Carl Roger’s theory and focuses on creating a supportive environment by emphasizing empathy and understanding. ST-CI does not utilize the main ingredients of Problem Solving Therapy (PST), Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT), CBT (Cognitive Behavior Therapy), and dynamic therapy. If patient agreed, willing and available caregivers were invited to participate in ST-CI.

Statistical Analysis

All participants with MADRS scores at baseline were included in the analysis, following the intent-to-treat principle. We used the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test (continuous variables) and the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact (categorical variables) to test differences between participants with suicidal ideation (N=32) vs. those without suicidal ideation (N=42) on demographics and baseline clinical variables (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of 74 Older Adults with Major Depression, Cognitive Impairment, and Disability by the Presence of Suicidal ideation

| Patients With Suicidal ideation (N=32) | Patients Without Suicidal ideation (N=42) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N Perc (%) | N Perc (%) | Fisher’s Exact (p) | ||||

| Gender | 0.42 | |||||

| Female | 22 | 68.75 | 33 | 78.57 | ||

| Race and Ethnicity | 0.03 | |||||

| Caucasian | 30 | 93.75 | 31 | 73.81 | ||

| African-American | 2 | 6.25 | 11 | 26.19 | ||

| Hispanic (all Caucasian) | 2 | 6.25 | 1 | 2.38 | 0.58 | |

| Probable Dementia | 15 | 46.88 | 24 | 57.14 | 0.48 | |

| Number of Depression Episodes (>=3) | 14 | 53.85 | 21 | 52.50 | 1.00 | |

| On Antidepressants | 21 | 65.63 | 26 | 61.90 | 0.74 | |

| On Cognitive Enhancers | 5 | 15.63 | 5 | 11.90 | 0.74 | |

| Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | z | p | |

| Age | 80.42 | 6.94 | 81.26 | 7.91 | −0.45 | 0.66 |

| Age at Onset of Depression | 55.27 | 25.60 | 61.24 | 26.33 | −1.99 | 0.05 |

| Education (years) | 13.32 | 2.83 | 12.96 | 3.22 | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| Attended Therapy Sessions# | 10.41 | 3.09 | 11.07 | 2.71 | −0.96 | 0.34 |

| MADRS1 Total Minus SI | 20.50 | 3.78 | 20.53 | 3.19 | −0.06 | 0.96 |

| MADRS1 Emotions Items | 12.75 | 2.45 | 11.69 | 2.24 | 2.07 | 0.04 |

| MADRS1 Cognitive | 1.81 | 1.09 | 2.45 | 0.88 | −2.24 | 0.03 |

| MADRS1 Energy | 2.34 | 1.21 | 2.21 | 1.14 | 0.56 | 0.57 |

| MADRS1 Vegetative | 3.59 | 1.91 | 4.17 | 1.79 | −1.54 | 0.12 |

| WHODAS-12 Total2 | 30.81 | 6.30 | 34.26 | 6.51 | −2.67 | 0.008 |

| DRS Total3 | 119.70 | 11.06 | 117.68 | 12.42 | 0.25 | 0.81 |

| Charlson Total4 | 3.06 | 2.95 | 3.05 | 2.14 | −0.59 | 0.55 |

| Intensity of Antidepressant Medication Treatment5 | 2.00 | 1.57 | 1.74 | 1.50 | 0.73 | 0.45 |

90.5% of subjects who completed the study had 12 therapy sessions, 6.3% had 11 sessions, and 3.2% had 10 session.

Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS);

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule – II – 12 items;

Mattis Dementia Rating Scale – Total Score;

Charlson Commorbity Index;

Composite Antidepressant Score (CAD) – Revised.

In all analyses we used mixed effects models for longitudinal data. We used “time C12” as time centered at 12 weeks and we also included “time C12 squared” when it significantly improved the model fit, based on the chi-square of the difference in −2 log likelihood. To test whether PATH participants had greater improvement in MADRS Negative Emotions over 12 weeks of treatment, we used a generalized linear mixed-effects model for longitudinal data. The effect of improved MADRS Negative Emotions on reduction in suicidal ideation was assessed using a mixed-effects logistic regression model that examined the effects of the difference of lagged and follow-up assessments of MADRS Negative Emotion scores to predict follow-up suicidal ideation (e.g. difference of scores of MADRS motions between week 4 and baseline, week 8 and week 4, and week 12 and week 8 predicts suicidal ideation at week 4, week 8 and week 12 respectively). The mixed model had a subject-specific random intercept and fixed effects for time. To assess the specificity of improved negative emotions on suicidal ideation, we explored the effects of MADRS Cognitive (MADRS 6: Concentration Difficulties), Energy (MADRS 7: Lassitude) and Vegetative items (MADRS 4 & 5: Reduced Sleep & Appetite) by adding each independent variable in separate mixed logistic regression models. We used the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. A two-tailed alpha level was used for each statistical test. All analyses were performed with SAS 9.2[28].

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

The 74 randomized participants were aged 80.90 years (SD=7.48) and had an average of 13 years of education (SD=3.06). They had moderate depression (mean MADRS total=21.24; SD 3.49), cognitive impairment scores associated with mild cognitive deficits to moderate dementia (mean DRS total=118.6; SD=11.72) and pronounced disability (mean WHODAS-II total=32.77; SD=6.61) (Table 1). Of the 74 randomized participants, 63 (86.4%) completed the 12-week treatment trial. Among those who dropped out of treatment (N=11), 6 were receiving PATH and 5 ST-CI.

At study entry, 43% of participants (N=32) had varying but mild degrees of suicidal ideation: 20.27% (N=15) of participants had thoughts that life is not worth living, 17.57% (N=13) had passive suicidal thoughts/death ideation, 4.05% (N=3) had active but uncommon suicidal ideation, and 1.35% (N=1) had active and common suicidal ideation without intent or harm. [17.57% (N=13)]. Participants with suicide ideation had lower disability scores (WHODAS-II total) than those without suicidal ideation (Table 1). Further, African-Americans were less likely to report suicidal ideation than Caucasians. Consequently, we used race and baseline disability scores as covariates in our analyses whenever either variable was significantly correlated with the outcome.

Improved MADRS Negative Emotions Are Associated with Reduced Suicidal ideation During Treatment

We used a mixed-effects logistic regression model with suicidal ideation grouping (patients with SI vs. those without SI) as the outcome and included the following predictors: time centered at 12 weeks (C12), MADRS Negative Emotions at study entry and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks afterwards and disability at study entry (WHODAS-II total). MADRS Negative Emotions were significantly associated with suicidal ideation during the course of treatment (F[1, 165]=12.73, p=0.0005). No other MADRs variable was significantly related to suicidal ideation over time, when added in the model; the effect of MADRS Emotions was significant even after controlling for multiple comparisons. Because caregiver involvement in treatment could serve to either hinder or enhance reduction of SI in cognitively impaired patients, we examined whether the degree of caregiver involvement in treatment (number of sessions the caregiver participated) was associated with suicidal ideation over time. There was no significant association of the degree of caregiver involvement with suicidal ideation over time.

PATH Improves MADRS Negative Emotions More than ST-CI During Treatment

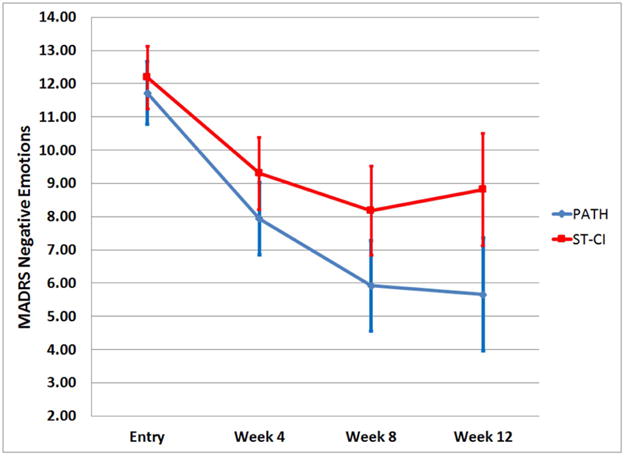

In a generalized linear mixed-effects model consisting of treatment group, time (C12), time squared (C12 × C12), treatment group by time (C12) interaction, and baseline disability, PATH participants had significantly greater reduction in MADRS Negative Emotions than ST-CI participants over the 12-week period (treatment group by time C12 interaction: F[1,63.2]=7.02, p=0.0102; Cohen’s D based on actual scores (95% CI) at: week 4: 0.38 (0–0.77); week 8: 0.64 (0.25–1.03); week 12: 0.75 (0.27–1.14)) (Figure 1). The effect was even stronger in those participants with greater MADRS Emotions scores at study entry [MADRS Emotions score ≥12 (Median), N=39]. In this subgroup, Cohen’s D (95%CI) based on actual scores at week 12 was 1.01 (0.68–2.08) (Mean Reduction [SD]: PATH: 7.79 (3.98) vs. ST-CI= 3.94 (5.57); post-hoc test: t[33.7]=2.49, p=0.0179). There were no significant differences between PATH and ST-CI participants on other variables (i.e. individual MADRS Cognitive, Energy, Vegetative Symptoms items or a sum of the rest of MADRS items).

Figure 1. The Course of MADRS Negative Emotions Items During 12 Weeks of PATH vs. ST-CI.

MADRS Negative Emotions scores over 12 weeks of PATH vs. ST in in 74 older adults with major depression, cognitive impairment and disability based on the least squares means and standard error of the mixed effects model: treatment, time C12 (centered at 12 weeks), time C12 squared, treatment × time C12, and baseline Whodas-II score.

Improved MADRS Negative Emotions Predict Reduction in Suicidal ideation

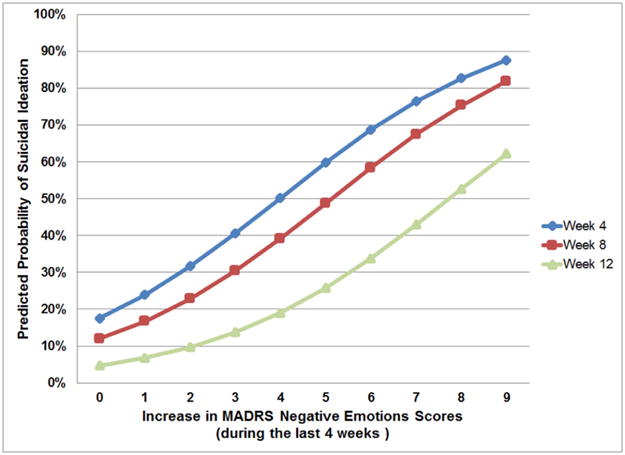

PATH and ST-CI participants had comparable improvement in suicidal ideation over 12 weeks of treatment. To examine whether improvement in negative emotions predicts reduction in suicidal ideation, a mixed effects logistic regression model was constructed in which the difference of MADRS Emotions scores between lagged and follow-up interview was used as a predictor of suicidal ideation grouping at follow-up interview. This difference significantly predicted suicidal ideation at follow-up interview (F[1, 96]=9.95, p=0.0022). For every point improvement in emotions (i.e. 1 point improvement of MADRS Emotions scores) between the lagged and follow-up assessment, the odds of suicidal ideation decreased by 32% (Odds Ratio=0.68; 95% CI: 0.53–0.86) (Figure 2). This effect was comparable in both treatment arms, was not mediated by improvements in cognition, energy, or vegetative symptoms, and was still significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons and after accounting for cognitive, energy and vegetative symptoms.

Figure 2. Predicted Probability of Suicidal Ideation at 4, 8 and 12 Weeks and Increase in MADRS Negative Emotions Item During the Preceding 4 Weeks.

Probability of suicidal ideation (SI) predicted by an increase in MADRS Negative Emotions score in the past four weeks. Blue line: Probability of SI at week 4 predicted by an increase in MADRS Negative Emotions score between baseline and week 4; Red line: Probability of SI at week 8 predicted by an increase in MADRS Negative Emotions score between week 4 and week 8; Green line: Probability of SI at week 12 predicted by an increase in MADRS Negative Emotions score between week 8 and week 12.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study are that improved negative emotions are associated with increased suicidal ideation and that improvement in negative emotions preceded and contributed to reduction in suicidal ideation in older adults receiving two home-delivered psychosocial interventions, i.e. PATH and ST-CI. The findings are clinically and heuristically important because improvement in negative emotions is a potential mechanism of action to reduce suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation is a risk factor for suicide attempts and suicides and it is a high clinical and research priority to reduce modifiable suicide risk factors[2,3,6,7]. Our premise is that older adults with depression and cognitive impairment have difficulty improving or regulating emotions because of impairment in the cognitive control system and in executive control abilities[18, 33, 4].

This is the first study, to our knowledge, that examines the course of suicidal ideation during home-delivered psychosocial treatments in a sample of older adults with major depression, a wide range of cognitive impairment (up to the level of moderate dementia), and disability. PATH targets emotion regulation and utilizes a problem-solving approach, compensatory strategies and caregiver involvement. ST-CI fosters a supportive environment, empathy and understanding. Even though ST-CI does not target emotion regulation, our findings indicate that it led to improvements in MADRS Negative Emotions. However, PATH participants had greater improvement in negative emotions over the course of treatment [Cohen’s D at Week 12: 0.75] than ST-CI participants. The effect size was even higher in those participants with higher levels of negative emotions at baseline [Cohen’s D at Week 12: 1.01].

Our results are consistent with findings demonstrating that negative affect intensity and reactivity is associated with suicidal ideation in older adults[11] and that increased negative emotions are associated with suicidal ideation and behavior in young and older adults[17,29–31]. Our findings reveal that reduction in suicidal ideation was similar in both study arms despite differential change in improvement in negative emotions. These findings may reflect: a) the improvement in MADRS emotions even in ST-CI participants (average improvement in MADRS Emotions over 12 weeks: 3.4) and b) the mild degree of suicidal ideation in our sample, which may be reduced with modest improvement in negative emotional states.

PATH follows the process model of emotion regulation, which posits that there are five broad strategies to regulate emotions: situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change and response modulation[27]. Our data did not permit an examination of the differential effects of emotion regulation strategies on improving emotions and reducing suicidal ideation. Understanding whether a specific emotion regulation strategy is most effective in improving negative emotions might guide the development of interventions to reduce suicidal ideation in our population.

Our study focuses on older adults with mostly mild forms of suicidal ideation. Most patients reported thoughts that life is not worth living (20%), and 23% (17/74) of the participants reported death (18%) or active suicidal ideation (5%). However, in addition to mild forms of suicidal ideation, our population manifested other independent suicide risk factors such as a diagnosis of major depression, cognitive impairment, disability, and increased medical burden, which elevate their suicide risk[34, 35]. Future investigations may examine whether elements of PATH could be re-purposed to decrease more prevalent wishes for death and thoughts of suicide by utilizing targeted emotion regulation techniques to reduce suicidal risk in high risk patients (e.g., patients with suicide intent, plan, or previous suicide attempts; or patients who were recently hospitalized). These patients are in need for a targeted intervention for indicated prevention of suicide[7].

The study has the following limitations. First, our study was not designed to answer our study questions and we used a single item (MADRS Suicide Item) to assess suicidality. The MADRS suicide item has been used in studies of suicidal ideation in older adults[9] but future investigations need to examine the course of suicidal ideation with more sensitive suicide instruments. Our study, however, fills a gap in the current literature on suicidal ideation in older adults with major depression and cognitive impairment. Research in this area is limited despite its public health significance.

Second, although we investigated the relationship of emotions with suicidal ideation and behavior[8–15,17,36], we used the MADRS, a scale designed to rate depression, to evaluate emotions associated with depression. Given the MADRS’s strong psychometric properties[37], one could argue that it is difficult to discern a reliable construct of emotions that meaningfully diverges from depression. Furthermore, the MADRS Negative Emotions subscale does not reflect cognitive distortions, an important concept for an emotion regulation intervention such as PATH. Nevertheless, our findings conclusively show that MADRS symptoms that do not pertain directly to improvement in emotions (i.e. sleep and appetite disturbances, concentration difficulties, lassitude) were not significantly correlated with suicidal ideation in our sample.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that negative emotions are related to suicidal ideation during the course of two psychosocial treatments in older adults with major depression and cognitive impairment. First, MADRS Negative Emotions were associated with suicidal ideation during 12 weeks of treatment. Second, participants who received PATH, a psychosocial treatment aimed to improve emotion regulation, had greater improvements in MADRS Emotions than participants who received ST-CI, another depression treatment. Finally, our most important finding demonstrates that improvement in MADRS Negative Emotions, and not improvements in other depression symptoms, mediates reduction in suicidal ideation in both treatments. Our findings can inform the development of psychosocial interventions for reduction of suicidal ideation in older adults with major depression and a wide range of cognitive impairment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following grants: NIMH K23 MH074659 & R01 MH091045 (PI: D.N. Kiosses), American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (PI: D. N. Kiosses), NARSAD (PI: D. N. Kiosses), and NIMH P30 MH085943 (PI: G.S. Alexopoulos).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Dr. Alexopoulos has received grant support from Forest; served as a consultant to Scientific Advisory Board of Pfizer and Janssen; and has been a member of speakers and bureaus sponsored by Takeda, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Sunovion. The rest of the authors do not have any financial relationships with commercial interests.

Clinical Trials Registration

Official Title: A Treatment for Depressed, Cognitively Impaired Elders

Identifier: NCT00368940

Contributor Information

Dimitris N. Kiosses, Associate Professor of Psychology in Clinical Psychiatry, Weill-Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College

James J. Gross, Professor of Psychology, Stanford University

Samprit Banerjee, Assistant Professor of Biostatistics, Department of Healthcare Policy and Research, Weill-Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College

Paul R. Duberstein, Professor of Psychiatry and Family Medicine, University of Rochester Medical Center

David Putrino, Assistant Professor, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, Director, Telemedicine and Virtual Rehabilitation, Burke Medical Research Institute

George S. Alexopoulos, Professor of Psychiatry, Weill-Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online] (Accessed 4/24/2016). Available from http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal_injury_reports.html.

- 2.Conwell Y, Van Orden K, Caine ED. Suicide in older adults. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34:451–68. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beautrais AL. A case control study of suicide and attempted suicide in older adults. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32:1–9. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.1.22184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richard-Devantoy S, Szanto K, Butters MA, Kalkus J, Dombrovski AY. Cognitive inhibition in older high-lethality suicide attempters. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30:274–83. doi: 10.1002/gps.4138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Draper B, Peisah C, Snowdon J, Brodaty H. Early dementia diagnosis and the risk of suicide and euthanasia. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.04.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cukrowicz KC, Ekblad AG, Cheavens JS, Rosenthal MZ, Lynch TR. Coping and thought suppression as predictors of suicidal ideation in depressed older adults with personality disorders. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12:149–57. doi: 10.1080/13607860801936714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention: Research Prioritization Task Force. A prioritized research agenda for suicide prevention: An action plan to save lives. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health and the Research Prioritization Task Force; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonson M, Skoog I, Marlow T, Mellqvist Fässberg M, Waern M. Anxiety symptoms and suicidal feelings in a population sample of 70-year-olds without dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1865–71. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cukrowicz KC, Duberstein PR, Vannoy SD, Lynch TR, McQuoid DR, Steffens DC. Course of suicide ideation and predictors of change in depressed older adults. J Affect Disord. 2009;113:30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heisel MJ, Flett GL, Besser A. Cognitive functioning and geriatric suicide ideation: testing a mediational model. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:428–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch TR, Cheavens JS, Morse JQ, Rosenthal MZ. A model predicting suicidal ideation and hopelessness in depressed older adults: the impact of emotion inhibition and affect intensity. Aging Ment Health. 2004;8:486–97. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331303775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conner KR, Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Seidlitz L, Caine ED. Psychological vulnerability to completed suicide: a review of empirical studies. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31:367–85. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.4.367.22048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capron DW, Norr AM, Macatee RJ, Schmidt NB. Distress tolerance and anxiety sensitivity cognitive concerns: testing the incremental contributions of affect dysregulation constructs on suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Behav Ther. 2013;44:349–58. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forkmann T, Scherer A, Böcker M, Pawelzik M, Gauggel S, Glaesmer H. The relation of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression to suicidal ideation and suicidal desire. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44:524–36. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marty MA, Segal DL, Coolidge FL. Relationships among dispositional coping strategies, suicidal ideation, and protective factors against suicide in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:1015–23. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.501068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Seidlitz L, Denning DG, Cox C, Caine ED. Personality traits and suicidal behavior and ideation in depressed inpatients 50 years of age and older. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55:P18–26. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.1.p18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seidlitz L, Conwell Y, Duberstein P, Cox C, Denning D. Emotion traits in older suicide attempters and non-attempters. J Affect Disord. 2001;66:123–31. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Segawa E, Yu L, Begeny CT, Anagnos SE, Bennett DA. The influence of cognitive decline on well-being in old age. Psychol Aging. 2013;28:304–13. doi: 10.1037/a0031196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuster J. The prefrontal cortex. London, UK: Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godefroy O, Azouvi P, Robert P, Roussel M, LeGall D, Meulemans T, Groupe de Réflexion sur l’Evaluation des Fonctions Exécutives Study Group Dysexecutive syndrome: diagnostic criteria and validation study. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:855–64. doi: 10.1002/ana.22117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiosses DN, Ravdin LD, Gross JJ, Raue P, Kotbi N, Alexopoulos GS. Problem adaptation therapy for older adults with major depression and cognitive impairment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:22–30. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiosses DN, Sirey J, MADRS Administration for Older Adults . Unpublished training manual. Weill Cornell Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ustun B. WHODAS-II Disability Assessment Schedule. NIMH Mental Health Research Conference; Washington, DC. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jurica PJ, Leitten CL, Mattis S. DRS-2 Dementia Rating Scale - 2 Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross JJ. Emotion Regulation: Conceptual and Empirical Foundations. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. 2nd. New York, NY: Guilford; 2014. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS version 9.2: SAS Institute, Cary NC

- 29.Szanto K, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Conwell Y, Begley AE, Houck P. High levels of hopelessness persist in geriatric patients with remitted depression and a history of attempted suicide. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1401–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb06007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rifai AH, George CJ, Stack JA, Mann JJ, Reynolds CF., 3rd Hopelessness in suicide attempters after acute treatment of major depression in late life. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1687–90. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.11.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sokero P, Eerola M, Rytsälä H, Melartin T, Leskelä U, Lestelä-Mielonen P, Isometsä E. Decline in suicidal ideation among patients with MDD is preceded by decline in depression and hopelessness. J Affect Disord. 2006;95:95–102.27. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phan KL, Wager T, Taylor SF, Liberzon I. Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: a meta-analysis of emotion activation studies in PET and fMRI. Neuroimage. 2002;16:331–48. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dombrovski AY, Butters MA, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Houck PR, Clark L, Mazumdar S, Szanto K. Cognitive performance in suicidal depressed elderly: preliminary report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:109–15. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180f6338d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Riley AA, Van Orden KA, He H, Richardson TM, Podgorski C, Conwell Y. Suicide and death ideation in older adults obtaining aging services. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:614–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Orden KA, Simning A, Conwell Y, Skoog I, Waern M. Characteristics and comorbid symptoms of older adults reporting death ideation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:803–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson WK, Gershon A, O’Hara R, Bernert RA, Depp CA. The prediction of studyemergent suicidal ideation in bipolar disorder: a pilot study using ecological momentary assessment data. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16:669–77. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carmody TJ, Rush AJ, Bernstein I, Warden D, Brannan S, Burnham D, Woo A, Trivedi MH. The Montgomery Asberg and the Hamilton ratings of depression: a comparison of measures. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16:601–11. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]