Abstract

To support sustained biomass accumulation, tumor cells undergo metabolic reprogramming. Nutrient transporters and metabolic enzymes are regulated by the same oncogenic signals that drive cell-cycle progression. Some of the earliest cancer therapies used antimetabolites to disrupt tumor metabolism, and there is now renewed interest in developing drugs that target metabolic dependencies. Many cancers exhibit increased demand for specific amino acids, and become dependent on either an exogenous supply or upregulated de novo synthesis. Strategies to exploit such ‘metabolic addictions’ include depleting amino acids in blood serum, blocking uptake by transporters and inhibiting biosynthetic or catabolic enzymes. Recent findings highlight the importance of using appropriate model systems and identifying target patient groups as potential therapies advance into the clinic.

Keywords: Cancer metabolism, amino acids, Warburg effect, glutaminase, CB-839, PHGDH

Introduction

The metabolic requirements of proliferating cells, including cancer cells, differ from those of quiescent cells. Proliferating cells must acquire and process metabolites to fulfill the biosynthetic demands of replication, while maintaining energy and redox homeostasis. This presents particular challenges within the tumor microenvironment, which is often poorly vascularized and depleted of nutrients including molecular oxygen. Consequently, cancer cells utilize a broad range of strategies to obtain metabolic fuels, such that ‘use of opportunistic modes of nutrient acquisition’ was recently described as a hallmark of cancer metabolism [1].

A seminal discovery in the field of cancer metabolism was made in the 1920s by Otto Warburg, who observed that tumor tissues consume glucose much more rapidly than surrounding healthy tissue, and ferment glucose to lactate regardless of oxygen availability (aerobic glycolysis or the Warburg effect) [2]. Subsequently, Harry Eagle noted that optimal proliferation of certain cultured mammalian cell lines requires a several-fold molar excess of glutamine over any other amino acid [3]. Indeed, glucose and then glutamine are the most rapidly consumed nutrients by many cultured cancer cell lines [4,5], although altered metabolism of fatty acids, acetate, nucleotides, folate, proteins and several amino acids besides glutamine has also been reported [1].

Cancer cell metabolism has been targeted by drugs since the advent of modern chemotherapy. In the late 1940s, the antifolate aminopterin was used to induce remission in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) patients. Aminopterin, supplanted in the 1950s by the related drug methotrexate, competitively inhibits dihydrofolate reductase and thereby blocks recycling of tetrahydrofolate, a carrier of ‘one-carbon units’ that has essential roles in amino acid and nucleic acid metabolism [6]. Today antifolates, along with antipyrimidines and antipurines, are routinely used to treat a range of cancers, illustrating the feasibility of targeting metabolism for cancer therapy.

Cancer cell amino acid metabolism

The 20 standard proteinogenic amino acids contribute to a diverse array of processes important for cell proliferation, including biosynthesis of proteins, nucleotides, lipids, glutathione, glucosamine and polyamines, and also replenishment (anaplerosis) of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle carbon. Concentrations of amino acids in blood serum and selected tissues are listed in Table S1 (see supplementary material online). Cellular amino acid metabolism is highly flexible, and varies remarkably with tissue of origin, cancer subtype, microenvironment and oncogenic driver mutations. Nevertheless, studies of cancer cell metabolism have revealed a number of common characteristics: (i) increased nitrogen demand to supply biosynthetic reactions; (ii) elevated consumption of amino acids and upregulation of corresponding transporters; (iii) demand for specific nonessential amino acids that exceeds intracellular supply, leading to dependence on exogenous sources; and (iv) altered levels of enzymes that catalyze amino acid synthesis and/or catabolism.

Another feature of amino acid metabolism in mammalian cells is a frequent apparent redundancy, with multiple enzymes catalyzing a given reaction. For instance, several enzymes convert glutamine to glutamate, including two mitochondrial glutaminases (GLS and GLS2) [7]. This inherent flexibility and redundancy presents challenges for targeting amino acid metabolism, and therefore selection of patient groups, consideration of resistance mechanisms and identification of drug synergies will be crucially important for developing successful therapies. Techniques to image metabolism in vivo will also be valuable for identifying the tumors most likely to respond to treatment [8]. Below, we describe strategies for targeting amino acid metabolism, with a focus on glutamine and serine – the most rapidly consumed nutrients after glucose by many cultured cancer cell lines [4,5].

Depletion of serum amino acids

Currently, the only anticancer agents that directly target amino acid metabolism are bacterial L-asparaginases (from Escherichia coli and Erwinia chrysanthemi), which are FDA-approved for treatment of pediatric and adult ALL. A potential complication of using bacterial enzymes is the production of neutralizing antibodies during treatment. PEGylation decreases immunogenicity and prolongs half-life, and PEGylated E. coli L-asparaginase is also FDA-approved for ALL therapy. Numerous clinical trials are currently evaluating the efficacy of L-asparaginases in treating a range of hematological malignancies [9].

Mammalian cells can generate asparagine from aspartate and glutamine via the enzyme asparagine synthetase (ASNS). However, some cancer cells, including leukemic lymphoblasts, lack expression of ASNS, and therefore rely on blood serum asparagine supply (i.e., they are asparagine auxotrophic). L-Asparaginases catalyze the deamidation of asparagine, resulting in a rapid depletion of this amino acid in serum [9]. Importantly, L-asparaginases also catalyze deamidation of glutamine. Because glutamine has diverse functions in cancer cell metabolism and is required for ASNS-mediated asparagine synthesis, serum glutamine depletion probably contributes to the therapeutic effects of L-asparaginases [9].

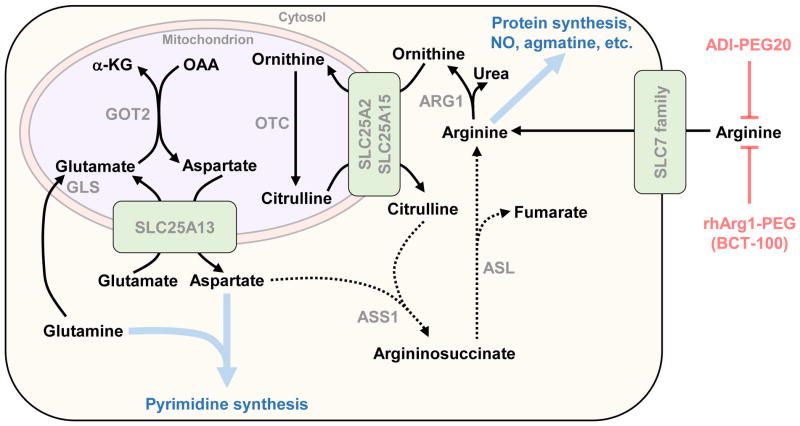

Similar approaches are being investigated for treatment of arginine auxotrophic tumors. The urea cycle enzyme argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS)1 catalyzes formation of argininosuccinate from citrulline and aspartate (Figure 1). Argininosuccinate in turn is converted by argininosuccinate lyase (ASL) to arginine. Although most cells can synthesize arginine de novo using this pathway, loss of ASS1 expression occurs in certain cancers, rendering them arginine auxotrophic [10]. ASS1-deficiency supports proliferation by increasing aspartate supply for pyrimidine synthesis (Figure 1) [11]. PEGylated bacterial arginine deiminase (ADI-PEG20) and recombinant human arginase 1 (rhArg1-PEG, or BCT-100) deplete serum arginine, and both are currently the subject of clinical trials (up to Phase III) [10]. As with L-asparaginase, a complication associated with bacterial-derived ADI-PEG20 is its immunogenicity. Although rhArg1-PEG lacks antigenicity, its KM for arginine is approximately tenfold higher than that of ADI-PEG20 [10]. A further potential limitation of this strategy is that cancer cells can rapidly develop resistance to arginine deprivation through re-expression of ASS1 [10].

Figure 1.

Plasma arginine depletion for cancer therapy. Clinical trials are currently evaluating PEGylated bacterial arginine deiminase (ADI-PEG20) and recombinant human arginase 1 (rhArg1-PEG, or BCT-100) for treatment of a variety of cancers. Certain tumors lose expression of argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS1), the enzyme that catalyzes formation of argininosuccinate from aspartate and citrulline. Consequently, these tumors are unable to synthesize arginine de novo (indicated by dotted lines), and rely on extracellular arginine supply and uptake through members of the SLC7 family of transporters. Loss of ASS1 benefits tumor cells by increasing aspartate supply for pyrimidine synthesis. By depleting plasma arginine, ADI-PEG20 and rhArg1-PEG/BCT-100 effectively starve these tumor cells of arginine. A potential mechanism for resistance to this treatment strategy is re-expression of ASS1, leading to restored de novo arginine synthesis. Thick blue arrows indicate multistep pathways and blue text indicates their products. Abbreviations: ARG1, arginase 1; ASL, argininosuccinate lyase; ASS1, argininosuccinate synthetase; GLS, glutaminase; GOT, aspartate aminotransferase; OTC, ornithine transcarbamylase.

Nitrogen transfer reactions: glutamine and its metabolic neighbors

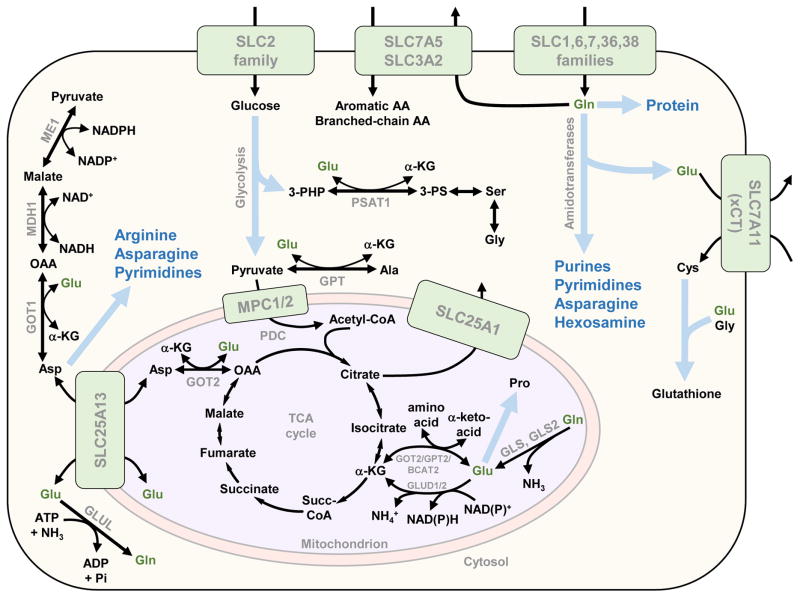

After glucose, the most rapidly consumed nutrient by many cultured cancer cell lines is glutamine [4,5], the most abundant amino acid in blood serum [7]. Although other amino acids, which are consumed at much lower rates than glutamine, collectively account for the majority of carbon mass in proliferating mammalian cells, glucose- and glutamine-derived carbon each still constitute 5–10% of total dry cell mass [5]. Glutamine is a major carbon source for nonessential amino acid synthesis (Figure 2), and therefore glutamine-derived carbon is over-represented in cellular protein [5]. Furthermore, the amide and α-nitrogen atoms of glutamine respectively account for 11% and 17% of cellular nitrogen in cultured lung cancer cells [5]. In rapidly proliferating cells including immune cells, enterocytes of the small intestine and some cancer cells, glutamine plays a major part in cellular energetics and redox homeostasis, in addition to supplying biosynthetic reactions with nitrogen and/or carbon (Figure 2) [7]. Indeed, although mammalian cells can synthesize glutamine de novo, elevated demand can render them dependent on an exogenous supply during rapid proliferation [7]. A number of oncogenic signaling pathways and transcription factors drive the reprogramming of cellular glutamine metabolism during tumorigenesis [7,12,13]. Although we focus below on glutamine catabolism as a potential therapeutic target, glutamine synthesis also has crucial roles in some cancer cells (Box 1).

Figure 2.

Glutamine/glutamate utilization in proliferating cells. Glutamine (Gln) and glutamate (Glu), shown in dark green text, donate carbon and/or nitrogen to diverse biosynthetic processes in proliferating cells. Glutamine is taken up from the extracellular environment by a number of SLC superfamily transporters, or synthesized de novo from glutamate and ammonia by glutamine synthetase (GLUL). A heterodimer of SLC7A5 (LAT1) and SLC3A2 couples glutamine efflux to uptake of aromatic and branched-chain amino acids, and SLC7A11 (xCT) couples glutamate efflux to cystine uptake. In the cytosol, glutamine donates its amide nitrogen (yielding glutamate) to a number of biosynthetic reactions catalyzed by glutamine amidotransferases, including reactions in the purine, pyrimidine and hexosamine biosynthetic pathways and also the asparagine synthetase reaction. In the mitochondrion, glutamine is converted to glutamate by glutaminases (GLS or GLS2), with the amide nitrogen released as ammonia. Cytosolic and mitochondrial glutamate can exchange via the aspartate/glutamate carrier SLC25A13. In the cytosol, glutamate together with glycine and cysteine form the antioxidant tripeptide glutathione. Reversible transaminases, some of which have cytosolic and mitochondrial isoforms, interchange glutamate and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), coupled to the interchange of α-ketoacids and amino acids including serine, alanine and aspartate. In the mitochondrion, glutamate can also be deaminated by glutamate dehydrogenase (GLUD1/2) to yield α-KG and ammonia. Glutamate can also be directly incorporated in the proline synthesis pathway. Thick blue arrows indicate multistep pathways and blue text indicates their products. Abbreviations: AA, amino acids;α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; BCAT, branched-chain amino transaminase; GLUL, glutamine synthetase; GLS/GLS2, glutaminase/glutaminase 2; GOT, aspartate aminotransferase; GPT, alanine transaminase; MDH, malate dehydrogenase; ME, malic enzyme; MPC, mitochondrial pyruvate carrier; OAA, oxaloacetate, PDC, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; 3-PHP, 3-phosphohydroxypyruvate; 3-PS, 3-phosphoserine; Succ-CoA, succinyl-Coenzyme A. Amino acids are denoted by their standard three-letter abbreviations.

Box 1. Metabolic profiles vary with tumor type and microenvironment.

A number of recent studies have highlighted the importance of considering tumor type, culture conditions and model system when investigating metabolism. Transitioning lung cancer cells from monolayer to anchorage-independent culture results in suppressed oxidation of glucose and glutamine [30]. Increased reductive metabolism of glutamine via cytosolic isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)1 instead occurs to generate citrate, which enters the mitochondrion and drives NADPH production via IDH2 to mitigate reactive oxygen species.

Metabolic phenotype can also change when cells are transitioned between in vivo and ex vivo model systems. Whereas utilization of exogenous glutamine by mutant KRAS-driven non-small-cell lung cancer tumors is minimal, cultured cell lines derived from these tumors are dependent on an external glutamine supply and are also sensitive to inhibition of glutaminase (GLS) [29]. Transplantation of cell lines back into mouse lungs yields tumors with a similar metabolic phenotype to the original tumor. Notably, the lung mediates net glutamine synthesis and release in healthy individuals, and an earlier study found that MYC-induced lung tumors upregulate glutamine synthetase (GLUL) and accumulate glutamine, in contrast to MYC-induced liver tumors which exhibit increased GLS-mediated glutamine catabolism and decreased GLUL expression [57]. Like lung tumors, gliomas accumulate glutamine, which they produce from glucose carbon via the TCA cycle and GLUL [58,59]. Glutamine in these tumors is used to fuel de novo purine synthesis rather than for TCA cycle anaplerosis. Consistently, GLS is present at much lower levels in orthotopic glioblastomas than in surrounding brain tissue [59].

In contrast to lung tumors and gliomas, GLS-mediated glutamine catabolism is upregulated and of clinical significance in many cancers [7]. GLS is highly overexpressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) relative to surrounding liver tissue, and also in MYC-driven HCC in mice [16]. Loss of one copy of GLS in this mouse model blunts tumor growth, and treatment with the GLS inhibitor bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,2,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)ethyl sulfide (BPTES) prolongs survival. Similarly, in a MYC-driven renal cell carcinoma mouse model, GLS is robustly upregulated and tumor growth is inhibited by BPTES [24]. Even different cancer subtypes show distinct metabolic phenotypes. For example, basal breast cancer cells are typically glutamine dependent and sensitive to GLS inhibition, whereas most luminal breast cancer cells express GLUL, are resistant to GLS inhibitors and are capable of glutamine-independent proliferation [25,60]. Adding further complexity, within the tumor microenvironment cancer-associated fibroblasts can synthesize glutamine via GLUL, and supply neighboring glutamine auxotrophic cancer cells [61,62].

All this highlights the importance of choosing appropriate model systems for studying cancer cell metabolism, and of recognizing the profound differences in metabolic phenotype that exist between different tumor types. A possible source of experimental artifacts, which is controllable and could be addressed in future studies, is the widespread use of cell culture media that contain nonphysiological concentrations of many nutrients including amino acids (see supplementary material online). For example, the concentration of glutamine in blood serum is approximately 0.5 mM in healthy individuals, and lower in many cancer patients [63], yet standard cell culture media contain 2–4 mM glutamine. This issue is potentially exacerbated in studies of brain tumor metabolism, because most amino acids (with the exception of glutamine) are maintained at concentrations 2–12-fold lower in cerebrospinal fluid than in serum [64].

At the organismal level, skeletal muscle, lung and adipose tissues mediate net de novo synthesis and release of glutamine, whereas net glutamine catabolism occurs in the kidney [7]. The liver exhibits net glutamine consumption coupled to urea production in the post-absorptive state, and net glutamine output during prolonged starvation. Glutamine transport across the plasma membrane is mediated by several members of the SLC superfamily of transporters, at least four of which are upregulated in cancers downstream of c-Myc [14]. The transporters SLC1A5 (ASCT2), which catalyzes sodium-dependent uptake of neutral amino acids, and SLC7A5 (LAT1), which can couple glutamine efflux to uptake of aromatic and branched-chain amino acids, have received particular attention as possible therapeutic targets [14]. To date, however, no high-affinity selective inhibitors of these proteins have been reported [14].

Intracellular glutamine catabolism begins with its conversion to glutamate, catalyzed either by glutamine amidotransferases, which donate the amide nitrogen of glutamine to biosynthetic reactions, or by mitochondrial glutaminases, which release it as ammonia. A number of enzymes contain glutamine amidotransferase domains, including asparagine synthetase, five enzymes in nucleotide biosynthesis pathways and glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase (GFPT)1, which catalyzes the rate-limiting step of hexosamine biosynthesis (Figure 2). There are two glutaminase genes in humans, GLS and GLS2, each of which encodes at least two isoforms as a result of alternative splicing or surrogate promoter mechanisms [7]. GLS is broadly expressed in mammalian tissues, most abundantly in kidney, brain, intestine and lymphocytes [15], and numerous reports indicate that it is pro-oncogenic and upregulated in a variety of cancers [7]. Expression of GLS2 is highest in liver, brain and pancreas, and the role of GLS2 in cancer appears to be context dependent [7]. It is upregulated by the tumor suppressor p53 but also by the proto-oncoprotein N-Myc and, although GLS2 is epigenetically silenced in some liver cancers [16], it is significantly overexpressed and pro-oncogenic in neuroblastoma, radiation-resistant cervical tumors, colorectal cancer and lung cancer [17–19].

Efforts to inhibit glutamine metabolism for cancer therapy date to the 1950s–1970s, when the glutamine antimetabolites 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON), azaserine and acivicin were found to have antitumor activity [20]. These molecules are nonselective inhibitors of glutamine-consuming enzymes, and their cytotoxicity arises primarily through inhibition of the amidotransferases involved in nucleotide biosynthesis. Despite promising preclinical data, clinical trials revealed excessive side-effects that preclude the use of these inhibitors as stand-alone agents. Recent research has instead focused on selectively inhibiting specific nodes of glutamine metabolism to minimize systemic toxicity [20,21].

To date, the strategy that has advanced furthest involves selective inhibition of GLS. RNAi-mediated knockdown of GLS expression or inhibition of GLS by the preclinical tool compounds 968 or bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,2,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)ethyl sulfide (BPTES) suppresses proliferation of glutamine-dependent cancer cells in vitro [22,23], and slows growth of tumor xenografts and MYC-driven mouse tumors in vivo [16,23,24]. The BPTES derivative CB-839 inhibits GLS much more potently than the parent molecule, and shows in vivo efficacy against triple-negative breast tumor and multiple myeloma xenografts [25,26]. CB-839 is currently being assessed in clinical trials, and has shown efficacy in some contexts [27,28]. Because utilization of glutamine varies with tumor type, microenvironment and cell culture conditions [29,30], consideration of model systems and selection of appropriate target cancers will be crucial for further developing this therapeutic approach (Box 1). Given the apparent importance of GLS2 in some cancer types, it will be of interest to determine whether it represents a second druggable glutaminase – and, indeed, whether it can provide tumors with a resistance mechanism to CB-839 treatment.

Asparagine synthetase (ASNS) is a glutamine amidotransferase that catalyzes ATP-dependent synthesis of asparagine and glutamate from aspartate and glutamine. Upregulation of ASNS expression renders leukemia cells resistant to L-asparaginase treatment, and ASNS is essential for cell survival in the absence of exogenous asparagine [31]. Overexpression of ASNS occurs in a number of solid tumors including gliomas and neuroblastomas, where it is associated with poor prognosis [31]. Combining L-asparaginase treatment with knockdown of ASNS expression simultaneously deprives cells of external and internal asparagine supplies, and potently inhibits tumor growth in vivo [32]. Attempts in the 1970s to target ASNS as a strategy for overcoming L-asparaginase resistance in leukemia cells failed to identify potent inhibitors. However, the available preclinical data indicate that further efforts to inhibit ASNS pharmacologically are justified.

A product of the glutaminases and the amidotransferases is glutamate, which is present at high intracellular concentration (~25 mM in HeLa cells [33]) and plays a central part in cellular amino acid metabolism. Major fates of glutamate include: (i) incorporation into polypeptide chains during protein synthesis; (ii) ligation with cysteine to form γ-glutamylcysteine, which is subsequently condensed with glycine to yield the antioxidant glutathione; (iii) efflux through antiporters coupled to uptake of extracellular amino acids; (iv) conversion to α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), with nitrogen either released as ammonium (deamination) or transferred to an α-ketoacid to generate the corresponding amino acid (transamination); and (v) diversion into the proline synthesis pathway (Figure 2). Of the glutamate antiporters, SLC7A11 (xCT) has received particular attention as a possible target for cancer therapy [34,35]. Glutamate efflux through SLC7A11 drives acquisition of cystine from the extracellular environment. Cystine is rapidly reduced in the cell to cysteine, which can then be used in protein and glutathione synthesis. Although the small molecules sulfasalazine, erastin and sorafenib block SLC7A11 function, each has other known targets and there is a need to develop more-selective inhibitors of this transporter [34,35].

Oxidative deamination of glutamate to α-KG is catalyzed by mitochondrial glutamate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 (GLUD1/2), and transaminations are catalyzed by several enzymes, some of which have mitochondrial and cytosolic isoforms (Figure 2). Proliferating mammary epithelial cells catabolize glutamate primarily through transaminases, coupling α-KG generation to nonessential amino acid synthesis [36]. As cells transition to quiescence, transaminase expression decreases and GLUD expression is upregulated. Consistent with these findings, highly proliferative human breast tumors display high transaminase and low GLUD expression, with expression of the transaminase genes PSAT1 (cytosolic serine synthesis), GPT2 (mitochondrial alanine synthesis) and GOT1 (cytosolic aspartate synthesis) correlating strongly with proliferation rate [36]. Oncogenic KRAS suppresses GLUD and upregulates GOT1 expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma as part of a metabolic program that supports redox homeostasis [12], and GPT2 is overexpressed in colon tumors, driving glutamine utilization for TCA cycle anaplerosis [37,38]. However, GLUD has important roles in certain tumors, and knockdown of GLUD1 expression in lung cancer cells inhibits tumorigenesis in a xenograft model [39].

Efforts to target transaminases and GLUD are currently preclinical, and there is a notable absence of inhibitors that are selective for individual transaminases. Aminooxyacetate, a pan-transaminase inhibitor, retards tumor growth in breast cancer xenograft models [40], and the GLUD1 inhibitor R162 suppresses growth of lung cancer xenografts [39]. The branched-chain amino acid transaminase 1 (BCAT1) is important for proliferation of IDH1-wild-type glioma cells and also for non-small-cell lung carcinoma allografts [41,42]. Although the FDA-approved drug gabapentin inhibits BCAT1, its Ki is in the millimolar range and more-potent inhibitors are probably necessary for effective BCAT1 inhibition in vivo.

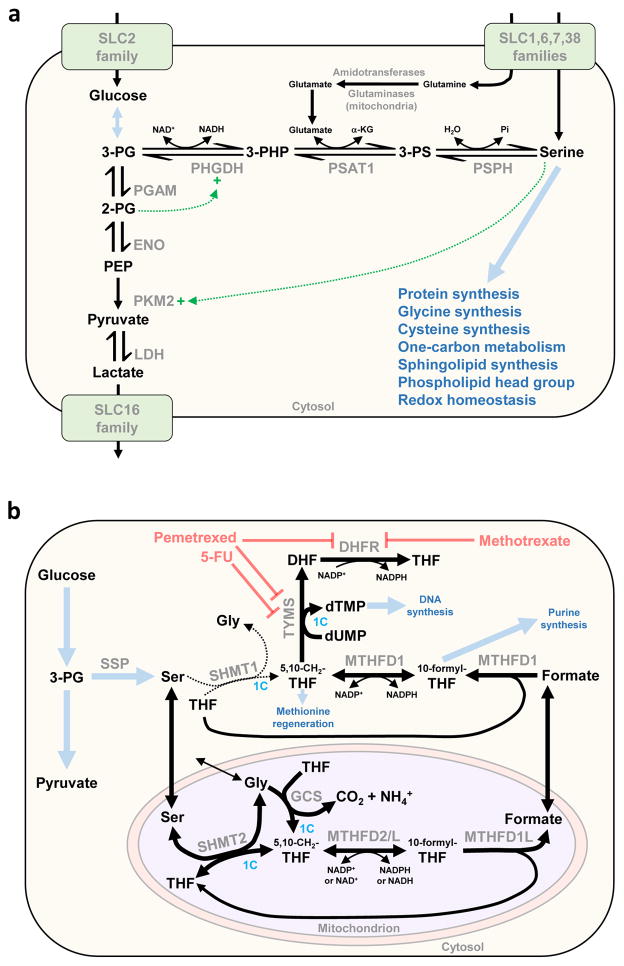

Serine/glycine and one-carbon metabolism

Altered serine metabolism in tumors was noted nearly half a century ago, and elevated flux through the de novo serine synthesis pathway (SSP) is a common phenomenon in cancer cells [43]. The SSP branches from glycolysis at the point of 3-phosphoglycerate and involves three sequential reactions, catalyzed by 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH), phosphoserine aminotransferase (PSAT)1 and phosphoserine phosphatase (PSPH) (Figure 3a). Even though up to 10% of glycolytic carbon can be diverted into this pathway [44], exogenous serine is still the third most rapidly consumed nutrient by cultured cancer cells [4,5]. Serine can be converted to glycine by serine hydroxymethyltransferases (cytosolic SHMT1 or mitochondrial SHMT2), donating a one-carbon unit to the folate pool which can ultimately be used in nucleotide biosynthesis (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Serine/glycine metabolism in proliferating cells. (a) The serine synthesis pathway (SSP). Serine can be imported from the extracellular environment by several members of the SLC superfamily of transporters, and it can also be synthesized de novo in the cytosol via the SSP. The SSP branches from glycolysis at the point of 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PG) and involves three sequential reactions catalyzed by 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH), phosphoserine aminotransferase (PSAT1) and phosphoserine phosphatase (PSPH). Up to 10% of glycolytic carbon is shunted into the SSP in cancer cells. The gene encoding PHGDH is recurrently amplified in a subset of human cancers, and is frequently overexpressed even in the absence of amplification. The endproduct of the SSP, serine, allosterically activates pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), allowing glycolytic flux to increase. Thus, when serine is depleted PKM2 activity becomes suppressed and glycolytic intermediates including 3-PG accumulate to supply the SSP. In addition, the glycolytic intermediate 2-phosphoglycerate (2-PG) activates PHGDH. Thick blue arrows indicate multistep pathways and blue text indicates their products. Dotted green line and ‘+’ symbol indicate enzymatic activation mechanisms. (b) Contribution of serine and glycine to one-carbon metabolism. In proliferating mammalian cells, the mitochondrial isoform serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2 (SHMT2), and not cytosolic SHMT1, is the primary catalyst of serine to glycine conversion (the SHMT1 reaction is indicated by a thin dotted line, and the SHMT2 reaction by a thick solid line, to illustrate the primary flow of carbon). The SHMT reaction transfers a one-carbon unit from serine to tetrahydrofolate (THF), generating glycine and 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate (5,10-CH2-THF). The mitochondrial glycine cleavage system (GCS) transfers a one-carbon unit from glycine to THF, also generating 5,10-CH2-THF. This intermediate is oxidized in the mitochondrion by methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2 (MTHFD2) or MTHFD2-like (MTHFD2L) to yield 10-formyl-THF. THF can be regenerated from 10-formyl-THF, with the release of formate, in a reaction catalyzed by MTHFD1L. After transport into the cytosol, formate is consumed by the trifunctional MTHFD1 along with cytosolic THF, generating cytosolic 10-formyl-THF, which is required for purine synthesis, and cytosolic 5,10-CH2-THF. The latter intermediate donates the one-carbon unit to convert deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) to deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP), a reaction catalyzed by thymidylate synthase (TYMS). The other product of the TYMS reaction, dihydrofolate, is converted back to tetrahydrofolate by the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR). TYMS is a target of the commonly used chemotherapy drugs pemetrexed and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and DHFR is a target of pemetrexed and methotrexate. Cytosolic 5,10-CH2-THF also donates a one-carbon unit for homocysteine methylation in the methionine cycle. Thick blue arrows indicate multistep pathways and blue text indicates their products. Reactions involving transfer of one-carbon units are highlighted with the text ‘1C’ in blue. Abbreviations:α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; ENO, enolase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PGAM, phosphoglycerate mutase; Pi, inorganic phosphate; 3-PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; SSP, serine synthesis pathway. Amino acids are denoted by their standard three-letter abbreviations.

Glycine in turn is required for nucleotide biosynthesis, directly supplying carbons for de novo purine biosynthesis, or donating a one-carbon unit to the folate pool via the mitochondrial glycine cleavage system (Figure 3b). Although glycine consumption was reported to correlate with proliferation rate [4], others have suggested that rapidly proliferating cells switch to glycine consumption only after exhausting exogenous serine [45]. Illustrating the importance of serine/glycine metabolism for oncogenic growth, TP53-null colorectal carcinoma cells cultured in serine-free medium exhibit oxidative stress and severely impaired proliferation and viability [45]. Because serine and glycine are nonessential amino acids, chronic depletion resulting from serine/glycine-free diets can be tolerated in vivo. Mice fed diets lacking serine and glycine display reduced colorectal xenograft tumor sizes and survive longer than mice fed control diets, indicating that therapeutic use of serine/glycine depletion is worthy of further investigation [45].

Mitochondrial SHMT2 is the primary catalyst for glycine production from serine, and one-carbon units are generated exclusively in mitochondria in most cultured cells (Figure 3b) [6,45]. Furthermore, SHMT2 is one of the most frequently overexpressed ‘metabolic genes’ in human tumors [46], and its knockdown severely impairs proliferation of cultured cancer cells [4]. Paradoxically, SHMT2 supports tumorigenesis under hypoxia in part by maintaining low intracellular serine levels. Serine is an allosteric activator of pyruvate kinase isoform M2 (PKM2) (Figure 3a), and therefore when intracellular serine is depleted PKM2 activity is suppressed and glycolytic intermediates accumulate [6]. By maintaining low serine concentrations, SHMT2 ensures low PKM2 activity and thus limits pyruvate supply for the TCA cycle (and consequent reactive oxygen species generation), providing a profound survival advantage for hypoxic glioma cells [47]. The survival advantage endowed by SHMT2 under hypoxia is dependent on clearance of the glycine product by the mitochondrial glycine cleavage system (GCS), and in particular the glycine decarboxylase (GLDC) component [47]. Notably, GLDC is overexpressed in some human cancers, and is reported to be one of the most upregulated genes in tumor-initiating cells isolated from non-small-cell lung cancer tumors [48]. SHMT2 and GLDC have been proposed as attractive therapeutic targets, and strategies to inhibit these enzymes are being pursued [6].

In 2011 it was discovered that the gene encoding PHGDH, which catalyzes the first reaction branching from glycolysis in the SSP (Figure 3a), is recurrently amplified in a subset of human cancers including breast tumors, where PHGDH amplification or overexpression is associated with triple-negative/basal subtypes and poor prognosis [44,49]. An RNAi-based loss-of-function screen in a human breast cancer xenograft model identified PHGDH as one of 16 metabolic genes required for in vivo tumorigenesis [49]. Knockdown of PHGDH in cancer cell lines with high expression severely impairs serine biosynthesis and cell proliferation. Reciprocally, ectopic expression of PHGDH in nontumorigenic MCF-10A cells induces some characteristics of cellular transformation [44,49]. Importantly, genetic loss of PHGDH in cancer cells cannot be rescued by supplemental serine or glycine (even though intracellular serine levels are restored), indicating that the SSP has a crucial role beyond generating serine [49]. The underlying mechanism for this finding is still unresolved [43].

Recently, two distinct small-molecule inhibitors of PHGDH were identified using high-throughput screens, both of which inhibit de novo serine biosynthesis and show selective toxicity to cancer cells with high SSP flux [50,51]. The inhibitor NCT-503, which has an IC50 of 2.5 μM, reduces the growth and weight of PHGDH-dependent breast tumor xenografts without affecting PHGDH-independent xenografts [50]. PHGDH inhibition suppresses production of labelled serine/glycine from [U-13C]glucose and incorporation of labeled one-carbon units derived from [U-13C]glucose into nucleotides (Figure 3b). Total intratumoral serine concentration is unaffected by PHGDH inhibition because of influx of extracellular serine, consistent with the cell culture studies described above. Indeed, when cells are cultured in medium containing [U13C]serine, PHGDH inhibition results in an increased intracellular pool of exogenous (labeled) serine. However, PHGDH inhibition decreases the incorporation of one-carbon units from extracellular serine into nucleotides. Instead, cytosolic SHMT1 becomes activated and consumes 5,10-CH2-THF and glycine to generate serine at the expense of nucleotide synthesis (Figure 3b). In the presence of the PHGDH inhibitor NCT-503, genetic deletion of SHMT1 permits the incorporation of exogenous serine-derived carbon units (via SHMT2 and the GCS) into nucleotide biosynthesis [50]. Thus, the development of PHGDH inhibitors has provided researchers with new tools to investigate PHGDH function in cancer cells but also represents an important step in the development of drugs that target the SSP.

Other potential targets

One of the most overexpressed metabolic genes in human tumors is PYCR1, which encodes pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 1, a mitochondrial enzyme in the pathway that synthesizes proline from glutamate (Figure 2) [46]. PYCR1 was identified as one of 16 essential metabolic genes in a breast cancer xenograft model [49], and its expression is upregulated by the oncogenic transcription factor c-Myc, which simultaneously downregulates enzymes that catalyze proline catabolism [52]. A recent study using ribosome profiling found that proline is the restrictive amino acid in kidney tumors and breast cancer xenografts (ribosomes were ‘stalled’ at proline codons) [53]. Thus, proline itself, rather than an intermediate or byproduct of the biosynthesis pathway, can be limiting for tumor growth. Although CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of PYCR1 has no effect on breast cancer cell proliferation in monolayer culture, it completely abolishes tumor formation in vivo [53]. These data indicate that the proline biosynthesis pathway, and in particular PYCR1, could be targeted for cancer therapy.

Finally, a distinct aspect of amino acid metabolism is being investigated as a target for cancer immunotherapy. The mutations that underlie cancer lead to expression of abnormal antigens by cancer cells but tumors acquire the ability to evade host immunosurveillance (tumor-induced tolerance) [54]. One of the mechanisms for tumor-induced tolerance involves indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which is overexpressed by most human tumors and catalyzes the rate-limiting reaction for tryptophan catabolism via the kynurenine pathway [55]. Both isoforms of IDO (IDO1 and IDO2) are overexpressed in cancer but research to date has focused on IDO1.

IDO activity limits the immune response by depleting tryptophan, which is essential for T cell proliferation, from the tumor microenvironment, and also by causing accumulation of the tryptophan metabolite kynurenine and its derivatives, which further inhibit immune cell proliferation [55]. Preclinical studies have shown that targeting IDO1 inhibits tumor growth and elicits an antitumor immune response in rodent models, and small-molecule inhibitors of IDO1 along with an IDO1-targeting vaccine are now being assessed in clinical trials [28,55]. Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO2) also catalyzes tryptophan degradation via the kynurenine pathway. Although TDO2 is normally present only in liver tissue and has a higher KM than IDO1 for tryptophan, it is also an immunosuppressive enzyme and is frequently upregulated in human tumors. Inhibition of TDO2 has shown promise in preclinical models [56] but is not currently being evaluated in clinical trials.

Concluding remarks

The past decade has seen rapid advances in our understanding of the metabolic reprogramming that occurs during tumorigenesis. Strategies to target specific nodes of cancer cell amino acid metabolism have progressed from preclinical studies to clinical trials, and are showing efficacy in some contexts. To date, research in this field has relied heavily on cancer cell lines grown in standard culture media. However, recent work reveals that remarkable metabolic adaptations can take place when cells are transitioned between microenvironments (Box 1). Furthermore, metabolic phenotypes differ greatly between tumor types, and even between distinct regions of a single tumor. This highlights the importance of recognizing the limitations of any particular model system for studying cancer metabolism. Drugs that target amino acid metabolism will probably be most effective as a component of personalized cancer therapy, with genetic and metabolomic biomarkers being assessed before selection of treatment strategy. A broader understanding of tumor metabolism in vivo, technological advances for imaging and profiling metabolism in patients, and continuing efforts to discover potent and selective inhibitors together have the potential to yield effective novel therapies for cancer.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Cellular metabolism is ‘reprogrammed’ to support tumorigenesis

Amino acids fulfill many metabolic requirements of proliferating cells

Specific metabolic pathways can be inhibited for cancer therapy

Microenvironment and culture conditions significantly impact metabolic phenotype

Drugs targeting amino acid metabolism are now undergoing clinical evaluation

Acknowledgments

We thank Cindy Westmiller for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Teaser: As efforts to target cancer cell amino acid metabolism advance from preclinical to clinical studies, recent findings identify novel potential strategies and highlight the impact of microenvironment on metabolic phenotype.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;23:27–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warburg O, et al. The metabolism of tumors in the body. J Gen Physiol. 1927;8:519–530. doi: 10.1085/jgp.8.6.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eagle H. Nutrition needs of mammalian cells in tissue culture. Science. 1955;122:501–514. doi: 10.1126/science.122.3168.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain M, et al. Metabolite profiling identifies a key role for glycine in rapid cancer cell proliferation. Science. 2012;336:1040–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.1218595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosios AM, et al. Amino acids rather than glucose account for the majority of cell mass in proliferating mammalian cells. Dev Cell. 2016;36:540–549. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang M, Vousden KH. Serine and one-carbon metabolism in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:650–662. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altman BJ, et al. From Krebs to clinic: glutamine metabolism to cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:619–634. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Challapalli A, Aboagye EO. Positron emission tomography imaging of tumor cell metabolism and application to therapy response monitoring. Front Oncol. 2016;6:44. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Covini D, et al. Expanding targets for a metabolic therapy of cancer: L-asparaginase. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2012;7:4–13. doi: 10.2174/157489212798358001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiu F, et al. Targeting arginine metabolism pathway to treat arginine-dependent cancers. Cancer Lett. 2015;364:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabinovich S, et al. Diversion of aspartate in ASS1-deficient tumours fosters de novo pyrimidine synthesis. Nature. 2015;527:379–383. doi: 10.1038/nature15529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Son J, et al. Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS-regulated metabolic pathway. Nature. 2013;496:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lukey MJ, et al. The oncogenic transcription factor c-Jun regulates glutaminase expression and sensitizes cells to glutaminase-targeted therapy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11321. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhutia YD, et al. Amino acid transporters in cancer and their relevance to “glutamine addiction”: novel targets for the design of a new class of anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1782–1788. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elgadi KM, et al. Cloning and analysis of unique human glutaminase isoforms generated by tissue-specific alternative splicing. Physiol Genomics. 1999;1:51–62. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.1999.1.2.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiang Y, et al. Targeted inhibition of tumor-specific glutaminase diminishes cell-autonomous tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2293–2306. doi: 10.1172/JCI75836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao D, et al. Myc promotes glutaminolysis in human neuroblastoma through direct activation of glutaminase 2. Oncotarget. 2015;6:40655–40666. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, et al. Epigenetic silencing of glutaminase 2 in human liver and colon cancers. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:601. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giacobbe A, et al. p63 regulates glutaminase 2 expression. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:1395–1405. doi: 10.4161/cc.24478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukey MJ, et al. Therapeutic strategies impacting cancer cell glutamine metabolism. Future Med Chem. 2013;5:1685–700. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katt WP, Cerione RA. Glutaminase regulation in cancer cells: a druggable chain of events. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19:450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le A, et al. Glucose-independent glutamine metabolism via TCA cycling for proliferation and survival in B cells. Cell Metab. 2012;15:110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang JB, et al. Targeting mitochondrial glutaminase activity inhibits oncogenic transformation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shroff EH, et al. MYC oncogene overexpression drives renal cell carcinoma in a mouse model through glutamine metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:6539–6544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507228112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross MI, et al. Antitumor activity of the glutaminase inhibitor CB-839 in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:890–901. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bromley-Dulfano S, et al. Antitumor activity of the glutaminase inhibitor CB-839 in hematological malignances. Blood. 2013;122:4226. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garber K. Cancer anabolic metabolism inhibitors move into clinic. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:794–795. doi: 10.1038/nbt0816-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullard A. Cancer metabolism pipeline breaks new ground. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:735–737. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davidson SM, et al. Environment impacts the metabolic dependencies of ras-driven non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Metab. 2016;23:517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang L, et al. Reductive carboxylation supports redox homeostasis during anchorage-independent growth. Nature. 2016;532:255–258. doi: 10.1038/nature17393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, et al. Asparagine plays a critical role in regulating cellular adaptation to glutamine depletion. Mol Cell. 2014;56:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hettmer S, et al. Functional genomic screening reveals asparagine dependence as a metabolic vulnerability in sarcoma. Elife. 2015;4:e09436. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen WW, et al. Absolute quantification of matrix metabolites reveals the dynamics of mitochondrial metabolism. Cell. 2016;166:1324–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dixon SJ, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. Elife. 2014;3:e02523. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Timmerman L, et al. Glutamine sensitivity analysis identifies the xCT antiporter as a common triple-negative breast tumor therapeutic target. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:450–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coloff JL, et al. Differential glutamate metabolism in proliferating and quiescent mammary epithelial cells. Cell Metab. 2016;23:867–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hao Y, et al. Oncogenic PIK3CA mutations reprogram glutamine metabolism in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11971. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith B, et al. Addiction to coupling of the Warburg effect with glutamine catabolism in cancer cells. Cell Rep. 2016;17:821–836. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin L, et al. Glutamate dehydrogenase 1 signals through antioxidant glutathione peroxidase 1 to regulate redox homeostasis and tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Korangath P, et al. Targeting glutamine metabolism in breast cancer with aminooxyacetate. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3263–3273. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayers JR, et al. Tissue of origin dictates branched-chain amino acid metabolism in mutant Kras-driven cancers. Science. 2016;353:1161–1165. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tönjes M, et al. BCAT1 promotes cell proliferation through amino acid catabolism in gliomas carrying wild-type IDH1. Nat Med. 2013;19:901–908. doi: 10.1038/nm.3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mattaini KR, et al. The importance of serine metabolism in cancer. J Cell Biol. 2016;214:249–257. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201604085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Locasale JW, et al. Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase diverts glycolytic flux and contributes to oncogenesis. Nat Genet. 2011;43:869–874. doi: 10.1038/ng.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maddocks OD, et al. Serine starvation induces stress and p53-dependent metabolic remodelling in cancer cells. Nature. 2013;493:542–546. doi: 10.1038/nature11743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nilsson R, et al. Metabolic enzyme expression highlights a key role for MTHFD2 and the mitochondrial folate pathway in cancer. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3128. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim D, et al. SHMT2 drives glioma cell survival in ischaemia but imposes a dependence on glycine clearance. Nature. 2015;520:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature14363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang WC, et al. Glycine decarboxylase activity drives non-small cell lung cancer tumor-initiating cells and tumorigenesis. Cell. 2012;148:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Possemato R, et al. Functional genomics reveal that the serine synthesis pathway is essential in breast cancer. Nature. 2011;476:346–350. doi: 10.1038/nature10350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pacold ME, et al. A PHGDH inhibitor reveals coordination of serine synthesis and one-carbon unit fate. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:452–458. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mullarky E, et al. Identification of a small molecule inhibitor of 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase to target serine biosynthesis in cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:1778–1783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521548113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu W, et al. Reprogramming of proline and glutamine metabolism contributes to the proliferative and metabolic responses regulated by oncogenic transcription factor c-MYC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8983–8988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203244109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loayza-Puch F, et al. Tumour-specific proline vulnerability uncovered by differential ribosome codon reading. Nature. 2016;530:490–449. doi: 10.1038/nature16982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prendergast GC. Immune escape as a fundamental trait of cancer: focus on IDO. Oncogene. 2008;27:3889–3900. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vacchelli E, et al. Trial watch: IDO inhibitors in cancer therapy. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e957994. doi: 10.4161/21624011.2014.957994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pilotte L, et al. Reversal of tumoral immune resistance by inhibition of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2497–2502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113873109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yuneva MO, et al. The metabolic profile of tumors depends on both the responsible genetic lesion and tissue type. Cell Metab. 2012;15:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tardito S, et al. Glutamine synthetase activity fuels nucleotide biosynthesis and supports growth of glutamine-restricted glioblastoma. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1556–1568. doi: 10.1038/ncb3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marin-Valencia I, et al. Analysis of tumor metabolism reveals mitochondrial glucose oxidation in genetically diverse human glioblastomas in the mouse brain in vivo. Cell Metab. 2012;15:827–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kung HN, et al. Glutamine synthetase is a genetic determinant of cell type-specific glutamine independence in breast epithelia. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002229. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao H, et al. Tumor microenvironment derived exosomes pleiotropically modulate cancer cell metabolism. Elife. 2016;5:e10250. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang L, et al. Targeting stromal glutamine synthetase in tumors disrupts tumor microenvironment-regulated cancer cell growth. Cell Metab. 2016;24:685–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Souba WW. Glutamine and cancer. Ann Surg. 1993;218:715–728. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199312000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Basun H, et al. Amino acid concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma in Alzheimer’s disease and healthy control subjects. J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect. 1990;2:295–304. doi: 10.1007/BF02252924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.