Abstract

Objective

To determine the association between neuroendocrine tumor (NET) biomarker levels and extent of disease as assessed by 68Ga DOTATATE PET/CT imaging.

Design

A retrospective analysis of a prospective database of patients with NETs.

Methods

Fasting plasma chromogranin A (CgA), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), gastrin, glucagon, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pancreatic polypeptide (PP), and 24-hour urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) levels were measured. Correlation between biomarkers and total 68Ga-DOTATATE-avid tumor volume (TV) was analyzed.

Results

The analysis included 232 patients. In patients with pancreatic NETs (n=112), 68Ga-DOTATATE TV correlated with CgA (r=0.6, p=0.001, Spearman). In patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (n=39), 68Ga-DOTATATE TV correlated with glucagon (r=0.5, p=0.02) and PP levels (r=0.5, p=0.049). In patients with von Hippel-Lindau (n=24), plasma VIP (r=0.5, p=0.02) and PP levels (r=0.7, p<0.001) correlated with 68Ga-DOTATATE TV. In patients with small intestine NET (SINET, n=74), 68Ga-DOTATATE TV correlated with CgA (r=0.5, p=0.02) and 5-HIAA levels (r=0.7, p<0.001), with 5-HIAA ≥8.1 mg/24h associated with metastatic disease with high positive (81.8%) and negative (85.7%) predictive values (p=0.001). 68Ga-DOTATATE TV in patients with NET of unknown primary (n=16) and those with NET of other primary location (n=30) correlated with 5-HIAA levels (r=0.8, p=0.002, and r=0.7, p=0.02, respectively).

Conclusions

Our data supports the use of specific NET biomarkers based on the site of the primary NET and the presence of hereditary syndrome-associated NET. High urinary 5-HIAA levels indicate the presence of metastatic disease in patients with SINET.

Keywords: neuroendocrine tumors, biomarkers, 68Ga-DOTATATE, tumor burden

Introduction

Most neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) originate from endocrine cells spread throughout the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Although these tumors tend to have an indolent natural course, NETs present with distant metastases in 40–50% of patients [1–3], usually to the liver and regional lymph nodes (LN), and less often to the lungs, brain, bones and peritoneal cavity[1].

Tumor biomarkers are important for diagnosis and follow-up of patients with NETs, especially after treatment of locally advanced and/or metastatic disease. Several biomarkers are used for NET surveillance, including plasma levels of chromogranin A (CgA), pancreatic polypeptide (PP), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and urinary 24-hour 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) levels depending on the primary tumor location [4,5]. The sensitivity and specificity of different biomarkers depend on the site of the primary tumor, with CgA mainly used for patients with pancreatic and midgut NET, NSE being most useful in patients with poorly differentiated NET, and 5-HIAA in patients with carcinoid syndrome. The accuracy of biomarker measurement depends on other factors unrelated to the tumor, such as kidney function and presence of gastric atrophy for CgA, and dietary factors and medical treatment for 5-HIAA[6]. Furthermore, the determination of whether elevated NET biomarkers accurately reflect the presence of disease has been limited by the “gold standard test” used for assessing the presence of disease; pathologic analysis, and/or the type of imaging modality. As a result of these limitations, there is a lack of consensus on the utility of these biomarkers for estimating the total tumor burden in patients with NETs [7].

Well-differentiated NETs typically express somatostatin receptors (SSTRs), thus radiolabeled somatostatin analogues have been used for diagnosis and follow-up of patients with NET [5]. 111In-pentetreotide (Octreoscan) has been widely used for NET imaging, but is limited by its low image resolution and long scan duration and relatively lower SSTRs affinity[8]. In contrast, the 68-Gallium (68Ga)-DOTA-compounds recently introduced into clinical practice (68Ga-DOTATATE, 68Ga-DOTANOC, 68Ga-DOTATOC), have been shown to have higher sensitivity for detecting NET than Octreoscan[9] and significantly impact the management of patients with NET [10,11].

To our knowledge, no study has yet assessed the utility of biochemical biomarkers for evaluating NET burden using the new generation DOTA-peptide based PET/CT imaging [12,13]. Thus, in this study we analyzed the correlation between biochemical biomarkers of NETs and total 68Ga-DOTATATE-avid tumor volume (TV), as a measure of total tumor burden in patients with NET.

Subjects and Methods

Study population

Patients known to have NETs based on imaging (CT, MRI, 18F-FDG PET), biochemical evidence of NETs, and/or pathologically confirmed NET were included in this study. The study was performed under an investigational new drug approval from the United States Food and Drug Administration. The full study eligibility criteria were as previously reported [10]. The study was approved by the National Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board and the National Institutes of Health Radiation Safety Committee (NCT01967537). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

NETs were sub-grouped according to the primary tumor location based on conventional anatomic imaging, 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT and/or pathological evaluation. Patients were subdivided into those with pancreatic NETs (PNETs) or small intestine NETs (SINETs). Subjects with metastatic NET and with pathologic 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake but no clear primary lesion were defined as NET of unknown primary (NEToUP, n=16). Thirty subjects with NET of other origins were grouped as NET of other primary location (NEToOL) due to their small number. Duodenal NETs were included in NEToOL due to their distinct characteristics compared with other SINET [14]. Tumor grade was determined according to the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) definitions as G1, G2 or G3 according to Ki-67 Index (<3%, 3–20% and >20%) and mitotic rate (<2, 2–20 and >20 per 10 high-power microscopic fields) in patients who had their tumor resected or biopsied, respectively[15].

Biochemical and Imaging Evaluation

All patients underwent testing for fasting plasma CgA, PP, NSE, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), gastrin and glucagon, and 24-hour 5-HIAA urinary collections. Thirty one patients receiving chronic treatment with proton-pump inhibitors and one patient with a plasma creatinine >2 mg/dl were excluded from the analysis of plasma CgA levels, as they may have an increase in plasma CgA levels that does not reflect disease burden. Plasma glucagon levels (LINCOplex Kit, Luminex 200, Missouri), plasma VIP levels (Peninsula Laboratories, California), and plasma PP levels (Mayo Medical laboratories, Rochester, Minnesota)[3] were measured using an immunoradiometric assay; whereas immunochemiluminometric assays were used for measuring plasma chromogranin A (Mayo Medical laboratories, Rochester, Minnesota), gastrin (Immulite 2000, Siemens, California), and NSE levels (NSE Kryptor, BRAHMS, Germany). Urinary 5-HIAA levels were measured using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (Mayo Medical laboratories, Rochester, Minnesota) [4]. The cut-offs for positivity were determined by the kit manufacturer or by the laboratory performing the tests.

Both 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT scans and biomarkers level measurements were performed concurrently at study inclusion. The biochemical evaluation for patients with a clinical suspicion of insulinoma included measurements of fasting glucose, insulin, proinsulin, and C-peptide during hypoglycemia. Supervised fasting test was conducted if necessary.

For 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT imaging, 185 MBq (5 mCi) 68Ga-DOTATATE was administered through a peripheral intravenous line. After approximately 60 minutes, the patient was positioned supine in a PET/CT scanner, and images were obtained from mid thighs to the top of the skull. A low-dose, non-contrast enhanced CT was used for attenuation correction and anatomic localization. Maximum standardized uptake values (SUVmax) of visualized lesions were calculated based on patient total body weight. Patients treated with long-acting somatostatin analogues were scanned before the next scheduled monthly dose while those on short-acting somatostatin analogues discontinued the drug 24 hours before imaging.

Quantification of tumor volume by 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT imaging

Disease burden was assessed by quantifying 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake using the MIM Vista workstation (version 6.5.9). A VOI (volume of interest) encompassing the entire scan was drawn and subsequently a SUVmax threshold-based approach was applied in order to include all sites of non-physiologic uptake. The SUV-threshold based technique for segmentation is commonly used and was tested in many clinical studies [16]. The software used in the current analysis enables automatic generation of separate VOIs encircling all areas above the SUVmax threshold set by the user. This software has been tested and reported before [17]. Afterwards, an experienced nuclear medicine physician who was blinded to the clinical and laboratory data manually excluded areas with physiologic 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake. The volumes of all lesions with a pathological 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake were obtained automatically. The sum of these volumes reflects the entire tumor tissue expressing somatostatin-receptor type 2, and was defined as total volume (TV).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise indicated. For group comparisons, the independent Student’s t-test were used to analyze differences in continuous variables and the chi-square test was used to analyze differences in categorical variables. The Pearson product was used for analysis of correlations between variables. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to assess the accuracy of 24-hour urinary 5-HIAA and plasma CgA levels for indicating metastatic SINET. Both TV and biochemical biomarker levels were logarithmically transformed to approximate normality. Non-parametric tests were used as appropriate, including Mann-Whitney U for continuous variables, and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The p value for significance was set at less than 0.05.

Results

The study cohort consisted of 232 patients with a mean age of 54.3±14.1 years, mean body-mass index of 28.9±6.8 Kg/m2, and 130 (56.0%) were females. The sites of NETs were PNET (n=112), SINET (n=74) and tumors of unknown primary (n=16). NEToOL consisted of gastric (n=6), duodenal (n=10), rectal (n=6), appendiceal (n=1), large intestine (n=2), bronchial (n=3), thymic (n=1) and bladder (n=1) NETs. The study cohort clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Mean biomarkers levels, normal reference ranges and percentage of patients with elevated biomarkers levels are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Study cohort clinical characteristics (n=232)

| Primary tumor n(%) | |

| PNET | 112 (48.3%) |

| SINET | 74 (31.9%) |

| Unknown primary | 16 (6.9%) |

| Other * | 30 (12.9%) |

| Genetic syndromes n(%) | |

| MEN-1 | 39 (16.8%) |

| VHL | 28 (12.1%) |

| NF-1 | 1 (0.4%) |

| Cowden | 1 (0.4%) |

| Functional status n(%) | |

| Nonfunctional | 121 (52.2%) |

| Insulinoma | 12 (5.2%) |

| Gastrinoma | 16 (6.9%) |

| Carcinoid syndrome | 79 (34.1%) |

| Other hormone production | 4 (1.7%) |

| WHO Tumor grade^ | |

| G1 | 51 (52.0%) |

| G2 | 42 (42.9%) |

| G3 | 5 (5.1%) |

| Metastases n(%) | |

| Any | 134 (57.8%) |

| Lymph nodes | 84 (36.2%) |

| Liver | 83 (35.8%) |

| Bones | 32 (13.8%) |

| Lungs | 12 (5.2%) |

| Treatment | |

| SSA n(%) | 79 (34.3%) |

| History of surgical resection of NETs before 68Ga-DOTATATE PET imaging | 133 (57.3%) |

| Pathological uptake on 68Ga-DOTATATE PET | 185 (79.7%) |

PNET, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor; SINET, small-intestine neuroendocrine tumor; MEN-1, multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 1; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau disease; NF-1, neurofibromatosis type 1; SSA, somatostatin analogues

consisted of gastric (n=6), duodenal (n=10), rectal (n=6), appendiceal (n=1), large intestine (n=2), bronchial (n=3), thymic (n=1) and bladder (n=1) NETs

Only a subset of patients had WHO tumor grade status available.

Table 2.

Neuroendocrine tumor biomarker levels distribution in study cohort

| Biomarker (n) Upper limit of normal range |

Mean±SD | Number (%) of patients with elevated biomarkers* |

|---|---|---|

| 24-hour urinary 5-HIAA levels (n=208) | ||

| ≤ 8 mg/24h | 10.5±22.9 | 48 (23.1%) |

| Plasma chromogranin A levels+ (n=83) | ||

| ≤ 93 ng/mL | 237±712 | 24 (28.9%) |

| Plasma NSE levels (n=81) | ||

| ≤ 15 ng/mL | 9.4±1.9 | 6 (7.4%) |

| Plasma gastrin levels (n=219) | ||

| ≤ 100 pg/mL | 176±661 | 42 (19.2%) |

| Plasma glucagon levels (n=220) | ||

| ≤ 80 pg/mL | 41.4±42.0 | 25 (11.4%) |

| Plasma VIP levels (n=169) | ||

| ≤ 75 pg/mL | 48.0±117.0 | 8 (4.7%) |

| Plasma PP levels (n=199) | ||

| ≤ 291pg/mL | 228±493 | 28 (14.1%) |

SD, standard deviation; 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; NSE, neuron-specific enolase; VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide; PP, pancreatic polypeptide

Based on upper limit of the reference range.

Patients with chronic kidney injury (n=1) and/or treatment with proton-pump inhibitors (n=31) were excluded from the analysis of chromogranin A.

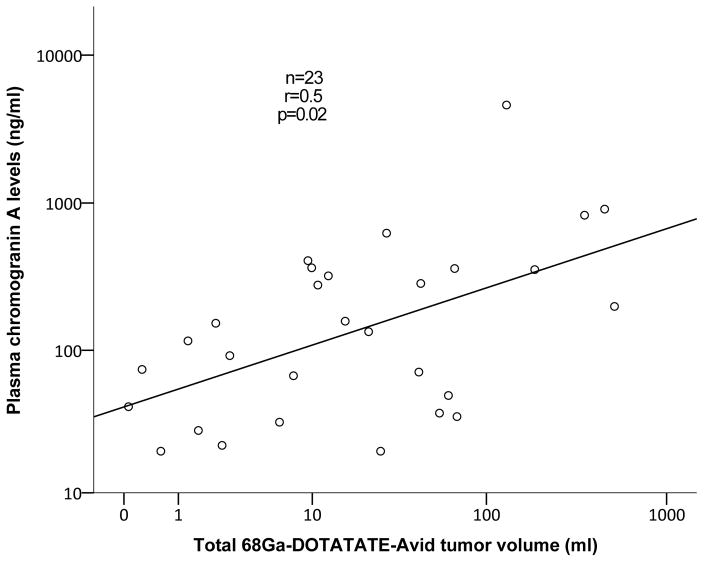

Tumor burden measurement by 68Ga-DOTATATE TV

The mean 68Ga-DOTATATE TV was 69.2±152.1 ml and mean SUVmax was 69.1±50.9. 68Ga-DOTATATE TV positively correlated with 24-hour urinary 5-HIAA levels (r=0.5, p<0.001) and plasma CgA levels (r=0.4, p=0.001). Patients with metastatic disease had higher 24-hour 5-HIAA levels (14.8±29.7 vs. 4.8±2.2 mg/24h, p<0.001), plasma gastrin levels (252±863 vs. 74±120 pg/ml, p=0.02), and plasma CgA levels (382±1030 vs.112±255 ng/ml, p=0.002) compared to patients without metastatic disease, respectively.

Tumor burden measurement in patients with PNET

Patients with PNETs (n=112) had mean 68Ga-DOTATATE TV of 71.3±167.5 ml and mean SUVmax of 85.5±58.3. Sixty-two patients with PNETs (55.4%) had metastatic disease at evaluation. Among patients with PNETs, tumor burden as measured by 68Ga-DOTATATE TV positively correlated with plasma CgA levels (r=0.6, p=0.001, Spearman’s rho), and plasma NSE levels had a similar trend (r=0.4, p=0.05). Similar trend was found for plasma NSE levels among patients with metastatic PNETs (r=0.5, p=0.07).

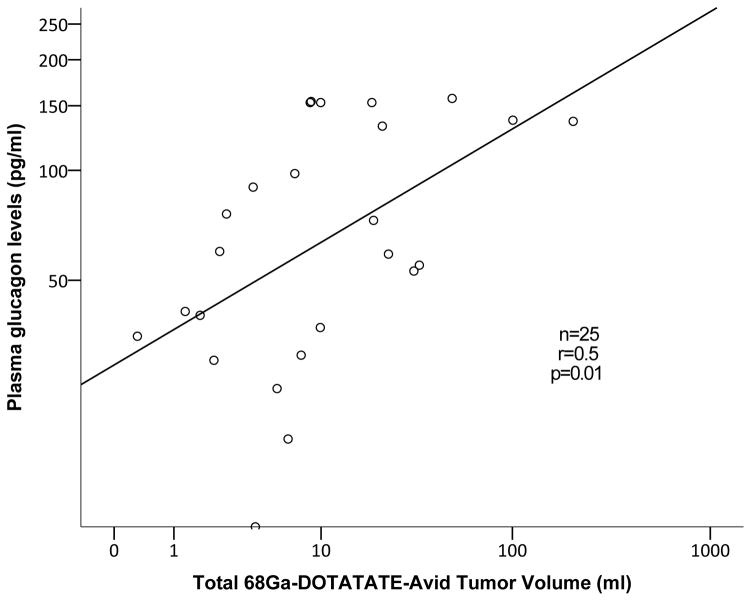

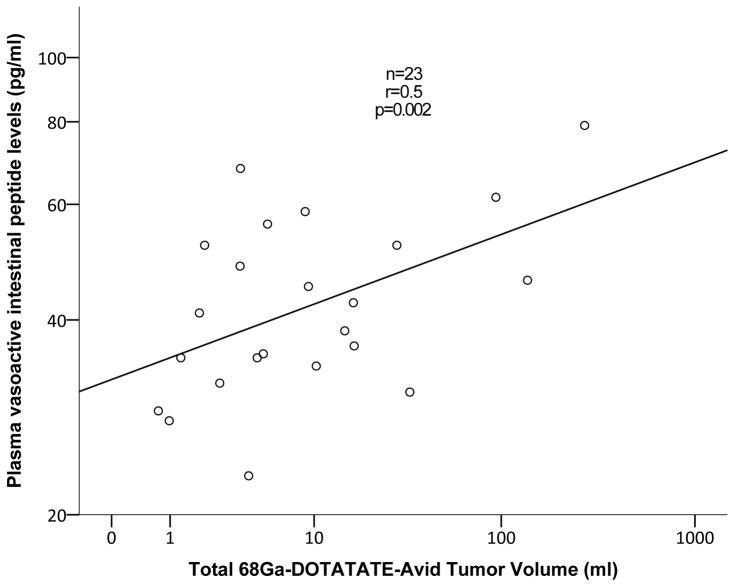

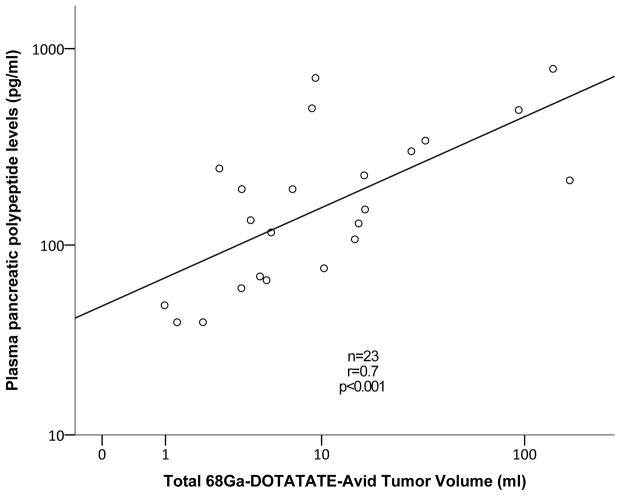

Among patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type-1 (MEN-1) with PNETs, 68Ga-DOTATATE TV positively correlated with plasma glucagon (r=0.5, p=0.01, Figure 1A) and PP levels (r=0.5, p=0.049). In patients with von Hippel-Lindau (VHL), 68Ga-DOTATATE TV positively correlated with plasma VIP (r=0.5, p=0.02, Figure 1B) and PP levels (r=0.7, p<0.001, Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Correlation analysis between 68Ga-DOTATATE-avid tumor volume of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors to plasma glucagon levels among patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type-1 (A), plasma pancreatic polypeptide and vasoactive intestinal-peptide levels among patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease (B and C, respectively)

Patients with WHO 2010 G1 PNETs had positive correlation between TV and plasma glucagon levels (n=22, r=0.5, p=0.02) that was not significant in patients with G2 PNETs (n=16). In 16 patients with gastrinomas of either pancreatic or duodenal location, 68Ga-DOTATATE TV had strong positive correlation with plasma gastrin levels (r=0.8, p=0.001).

Tumor burden measurement in patients with SINET

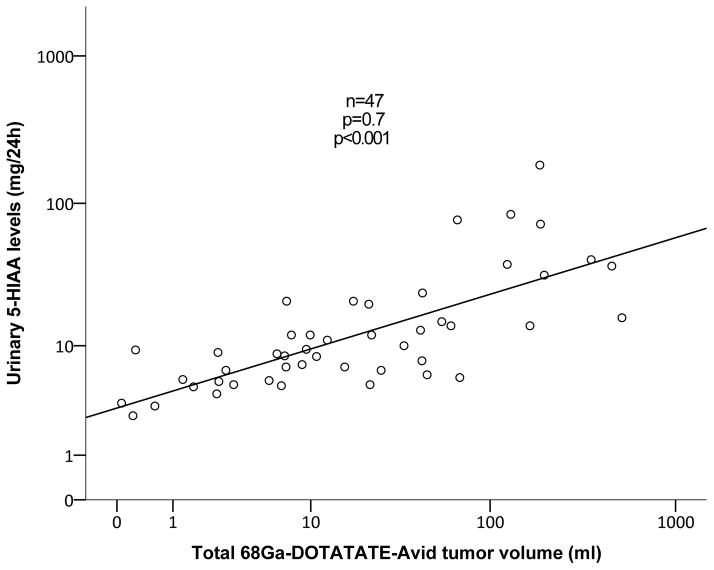

In patients with SINET (n=74), the mean 68Ga-DOTATATE TV and SUVmax were 74.1±133.5 ml and 49.1±25.9, respectively. 24-hour urinary 5-HIAA (p<0.001) levels were higher among patients with distant metastases compared with patient without metastases. The burden of SINET as measured by 68Ga-DOTATATE TV correlated positively with plasma CgA levels (r=0.5, p=0.02; Figure 2A) and with 24-hour urinary 5-HIAA levels (r=0.7, p<0.001; Figure 2B). Similarly, among the subgroup of patients with metastatic SINET, 68Ga-DOTATATE TV had positive correlation with CgA levels (r=0.5, p=0.02) and with 24-hour urinary 5-HIAA levels (r=0.7, p<0.001). In patients with carcinoid syndrome (n=32), 68Ga-DOTATATE TV correlated with 24-hour urinary 5-HIAA (r=0.7, p<0.001) and plasma CgA levels (r=0.5, p=0.02), whereas in patients without carcinoid syndrome 68Ga-DOTATATE TV correlated only with 24-hour urinary 5-HIAA levels (n=15, r=0.9, p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Correlation analysis between 68Ga-DOTATATE-avid tumor volume to plasma chromogranin A and 24-hour 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in patients with small intestine neuroendocrine tumors (A and B, respectively).

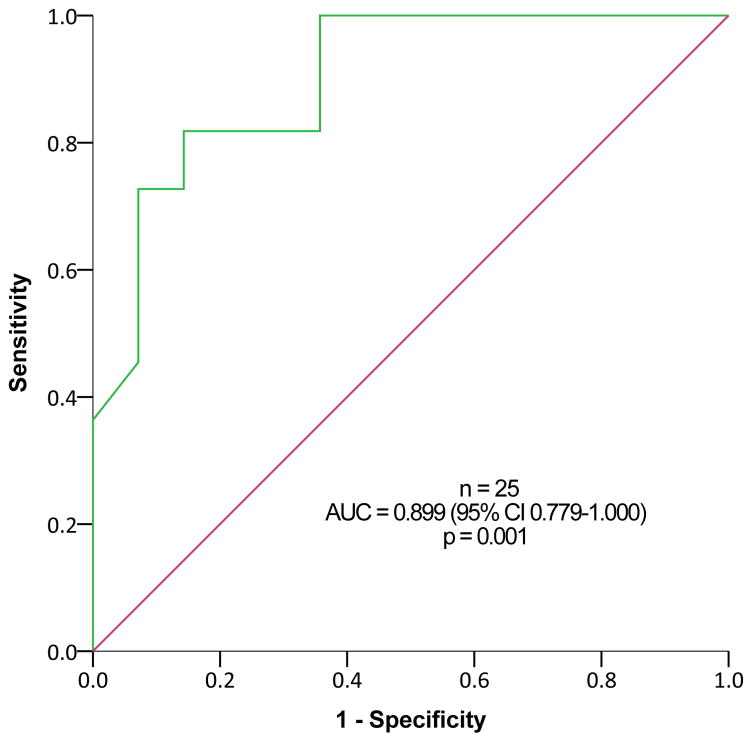

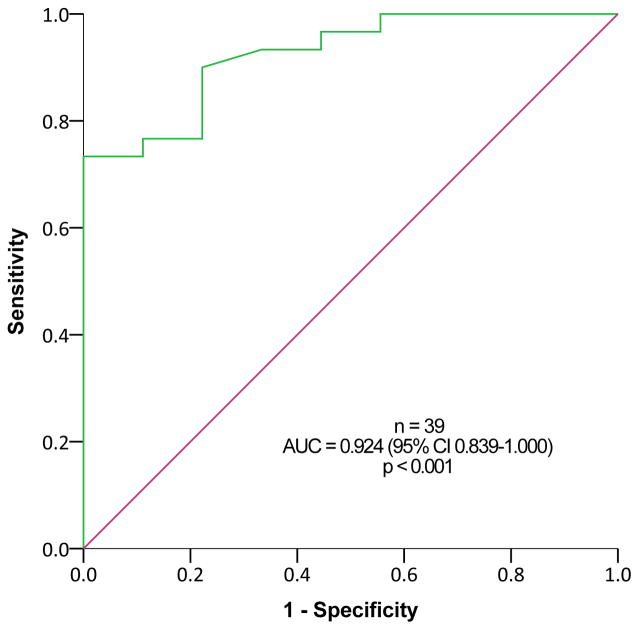

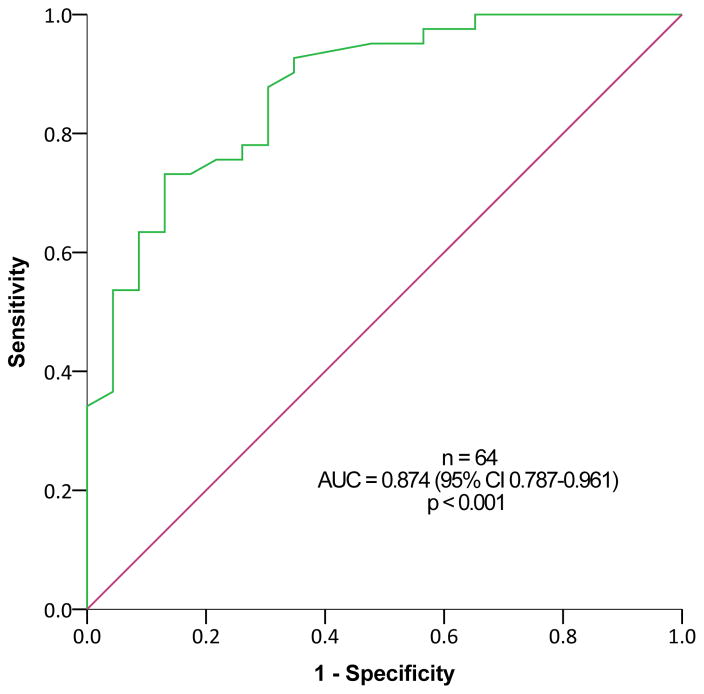

Urinary 5-HIAA levels ≥8.1 mg/24h (upper limit of normal range, 8 mg/24h) predicted metastatic disease based on 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT among subjects with SINET that were not treated with somatostatin analogues, with a sensitivity of 81.8% and a specificity of 85.7%, and positive and negative predictive value of 81.8% and 85.7%, respectively (p=0.001, Figure 3A). This was true also among patients treated with somatostatin analogues (Figure 3B) and among all subjects with SINET (Figure 3C). In contrast, ROC curve analysis revealed limited utility of plasma CgA levels for predicting metastatic SINET (area under the curve = 0.668, 95% confidence interval 0.548–0.788, p=0.008).

Figure 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis for 24-hour urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) levels for predicting metastatic disease in subjects with small-intestine neuroendocrine tumors (SINETs). Patients with (A) and without (B) somatostatin analogues treatment, and including all SINET patients (C).

Tumor burden measurement in NEToUP and NEToOL

Among sixteen patients with NEToUP correlation analysis revealed strong correlation between 68Ga-DOTATATE TV and 24-hour urinary 5-HIAA levels (r=0.8, p=0.002; Figure 4). Subjects with NEToOL (n=30) had positive correlation between 68Ga-DOTATATE TV and 24-hour 5-HIAA (r=0.7, p=0.02, Spearman’s rho).

The analyses were repeated after excluding patients treated with somatostatin analogues with findings similar to those described for the whole study cohort analysis. Among subjects with NEToOL, excluding patients with somatostatin analogue treatment revealed a correlation between 68Ga-DOTATATE TV and plasma PP levels (n=7, r=0.8, p=0.03).

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the utility of seven biomarkers for assessing NET burden using a novel tumor burden measurement approach based on 68Ga-DOTATATE TV in a large cohort of patients with NET. 68Ga-DOTATATE TV correlated strongly with urinary 5-HIAA and with plasma CgA among patients with SINETs. In addition, MEN-1 patients with PNETs had correlation between tumor burden and plasma glucagon levels, and subjects with VHL disease had correlation between 68Ga-DOTATATE TV and plasma PP and VIP levels. Finally, urinary 5-HIAA levels ≥8.1 mg/24h was associated with metastatic disease in patients with SINET, independent of somatostatin analogue treatment.

Tumor biomarkers measurement are the cornerstone of NET diagnosis[18], and are essential for surveillance after various treatment modalities are carried out. Plasma CgA levels reflect tumor burden in non-functioning PNETs[19], and high urinary 5-HIAA was found mainly in patients with metastatic SINET[20], and is associated with carcinoid heart disease [21]. Indeed, the current guidelines for NET management recommend the use of urinary 5-HIAA for SINET diagnosis, and the measurement of CgA and NSE for the diagnosis of PNET [4,5]. The current study provides data to support these recommendations of using specific NET biomarkers based on the primary tumor site and that elevated values of urinary 5-HIAA for SINET often indicates the presence of metastatic disease which may not be seen by conventional anatomic imaging studies.

Somatostatin receptor based PET/CT is a very sensitive imaging modality to detect NETs [10,22,23]. 68Ga-labeled somatostatin analogue PET/CT is more sensitive for NET localization[5,10], is faster, and requires lower radiation dose[24] compared with Octreoscan. Hence, in the current study, disease extent was assessed by quantification of whole body 68Ga-DOTATATE pathological uptake. Thus, we believe our analysis of the levels of a comprehensive panel of NET biomarkers and NET disease burden more accurately reflects the diagnostic and surveillance clinical utility of biomarkers in patients with NET.

Total 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake in NETs was reported in the past in a series of patients, but not in specific subtypes of NET, and no correlation analysis with tumor biomarkers was reported [12,13]. Moreover, the correlations between tumor biomarkers and tumor burden reported in the past have been based on anatomical imaging[19], counting the number of lesions[10], presence/absence of liver metastases[25] and not based on accurate total tumor volume measurements, as performed in the current analysis. The strong correlation between 24-hour urinary 5-HIAA levels and 68Ga-DOTATATE TV in SINET is not surprising[20], and might explain the strong correlation between total volume measurements and 5-HIAA among patients with NEToUP, as these tumors arise mainly from the small intestine but are not detected[26].

Our findings have important clinical implications. First, baseline 5-HIAA levels ≥8.1 mg/24h should prompt evaluation for metastatic disease in patients with SINET. Second, among patients with NET associated with hereditary syndromes, PP may be used as a biomarker for PNETs, as well as, glucagon and VIP in patients MEN-1 and VHL, respectively.

Our analysis has some limitations. First, the vast majority of the patients in the current study had gastro-entero-pancreatic (GEP) NETs, limiting the ability to make strong conclusions about biomarkers utility among patients with primary tumors at other sites. Second, although the analysis was performed by an experienced nuclear medicine specialist that was blinded to the clinical context, interobserver variation was not tested for in the current study, and should be evaluated in future studies. Third, plasma CgA levels may be elevated in patients with atrophic gastritis and can lead to positive results and every patient in the current study did not have endoscopy and biopsy to determine the presence of this. Finally, the biochemical biomarkers in the current analysis were performed using a single method per biomarker. Since there might be a difference in the measured levels between different analytical methods, the study results may only apply to the methods used in our study and other analytical methods would need to be studied in the future.

In conclusion, our data supports the use of specific NET markers based on the site of the primary NET, and the presence of hereditary syndrome associated NET. High levels of 24-hour urinary 5-HIAA commonly indicate the presence of metastatic disease in patients with SINET. The heterogeneity of patients with NET necessitates careful matching of biochemical biomarker for each patient according to both tumor and patient characteristics, and might justify personalized biomarker panel evaluation for tumor burden assessment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- 1.Pavel M, O’Toole D, Costa F, Capdevila J, Gross D, Kianmanesh R, Krenning E, Knigge U, Salazar R, Pape U-F, Öberg K Vienna Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Distant Metastatic Disease of Intestinal, Pancreatic, Bronchial Neuroendocrine Neoplasms (NEN) and NEN of Unknown Primary Site. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:172–85. doi: 10.1159/000443167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, Svejda B, Kidd M, Modlin IM. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America. 2011;40:1–18. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frilling A, Modlin IM, Kidd M, Russell C, Breitenstein S, Salem R, Kwekkeboom D, Lau W, Klersy C, Vilgrain V, Davidson B, Siegler M, Caplin M, Solcia E, Schilsky R Working Group on Neuroendocrine Liver Metastases. Recommendations for management of patients with neuroendocrine liver metastases. The Lancet Oncology. 2014;15:e8–21. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, Bartsch DK, Capdevila J, Caplin M, Kos-Kudla B, Kwekkeboom D, Rindi G, Klöppel G, Reed N, Kianmanesh R, Jensen RT participants all other VCC. Neuroendocrinology. Vol. 103. Karger Publishers; 2016. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Patients with Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Non-Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors; pp. 153–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niederle B, Pape U-F, Costa F, Gross D, Kelestimur F, Knigge U, Öberg K, Pavel M, Perren A, Toumpanakis C, O’Connor J, O’Toole D, Krenning E, Reed N, Kianmanesh R participants all other VCC. Neuroendocrinology. Vol. 103. Karger Publishers; 2016. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Jejunum and Ileum; pp. 125–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnold R, Chen Y-J, Costa F, Falconi M, Gross D, Grossman AB, Hyrdel R, Kos-Kudła B, Salazar R, Plöckinger U Mallorca Consensus Conference participants & European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumors: follow-up and documentation. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;90:227–33. doi: 10.1159/000225952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberg K, Modlin IM, De Herder W, Pavel M, Klimstra D, Frilling A, Metz DC, Heaney A, Kwekkeboom D, Strosberg J, Meyer T, Moss SF, Washington K, Wolin E, Liu E, Goldenring J. Consensus on biomarkers for neuroendocrine tumour disease. The Lancet Oncology. 2015;16:e435–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00186-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santhanam P, Chandramahanti S, Kroiss A, Yu R, Ruszniewski P, Kumar R, Taïeb D. Nuclear imaging of neuroendocrine tumors with unknown primary: why, when and how? European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2015;42:1144–55. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreiter NF, Bartels A-M, Froeling V, Steffen I, Pape U-F, Beck A, Hamm B, Brenner W, Röttgen R. Searching for primaries in patients with neuroendocrine tumors (NET) of unknown primary and clinically suspected NET: Evaluation of Ga-68 DOTATOC PET/CT and In-111 DTPA octreotide SPECT/CT. Radiology and oncology. 2014;48:339–47. doi: 10.2478/raon-2014-0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadowski SM, Neychev V, Millo C, Shih J, Nilubol N, Herscovitch P, Pacak K, Marx SJ, Kebebew E. Prospective Study of 68Ga-DOTATATE Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography for Detecting Gastro-Entero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Unknown Primary Sites. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34:588–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deroose CM, Hindie E, Kebebew E, Goichot B, Pacak K, Taieb D, Imperiale A. Molecular Imaging of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Current Status and Future Directions. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.179234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdulrezzak U, Kurt YK, Kula M, Tutus A. Combined imaging with 68Ga-DOTA-TATE and 18F-FDG PET/CT on the basis of volumetric parameters in neuroendocrine tumors. Nuclear medicine communications. 2016;37:874–81. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cieciera M, Kratochwil C, Moltz J, Kauczor HU, Holland Letz T, Choyke P, Mier W, Haberkorn U, Giesel FL. Semi-automatic 3D-volumetry of liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumors to improve combination therapy with 177Lu-DOTATOC and 90Y-DOTATOC. Diagnostic and interventional radiology (Ankara, Turkey) 22:201–6. doi: 10.5152/dir.2015.15304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato Y, Hashimoto S, Mizuno K-I, Takeuchi M, Terai S. Management of gastric and duodenal neuroendocrine tumors. World journal of gastroenterology. 2016;22:6817–28. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i30.6817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Coppola D, Lloyd RV, Suster S. The pathologic classification of neuroendocrine tumors: a review of nomenclature, grading, and staging systems. Pancreas. 2010;39:707–12. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ec124e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster B, Bagci U, Mansoor A, Xu Z, Mollura DJ. A review on segmentation of positron emission tomography images. Computers in Biology and Medicine. 2014;50:76–96. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etchebehere EC, Araujo JC, Fox PS, Swanston NM, Macapinlac HA, Rohren EM. Prognostic Factors in Patients Treated with 223Ra: The Role of Skeletal Tumor Burden on Baseline 18F-Fluoride PET/CT in Predicting Overall Survival. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2015;56:1177–84. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.158626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ardill JES, Erikkson B. The importance of the measurement of circulating markers in patients with neuroendocrine tumours of the pancreas and gut. Endocrine-related cancer. 2003;10:459–62. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han X, Zhang C, Tang M, Xu X, Liu L, Ji Y, Pan B, Lou W. The value of serum chromogranin A as a predictor of tumor burden, therapeutic response, and nomogram-based survival in well-moderate nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors with liver metastases. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2015;27:527–35. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norheim I, Oberg K, Theodorsson-Norheim E, Lindgren PG, Lundqvist G, Magnusson A, Wide L, Wilander E. Malignant carcinoid tumors. An analysis of 103 patients with regard to tumor localization, hormone production, and survival. Annals of surgery. 1987;206:115–25. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198708000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zuetenhorst JM, Bonfrer JMGM, Korse CM, Bakker R, van Tinteren H, Taal BG. Carcinoid heart disease: the role of urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid excretion and plasma levels of atrial natriuretic peptide, transforming growth factor-beta and fibroblast growth factor. Cancer. 2003;97:1609–15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deppen SA, Blume J, Bobbey AJ, Shah C, Graham MM, Lee P, Delbeke D, Walker RC. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. Vol. 57. Society of Nuclear Medicine; 2016. 68Ga-DOTATATE Compared with 111In-DTPA-Octreotide and Conventional Imaging for Pulmonary and Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis; pp. 872–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skoura E, Michopoulou S, Mohmaduvesh M, Panagiotidis E, Al Harbi M, Toumpanakis C, Almukhailed O, Kayani I, Syed R, Navalkissoor S, Ell PJ, Caplin ME, Bomanji J. The Impact of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT Imaging on Management of Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors: Experience from a National Referral Center in the United Kingdom. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2016;57:34–40. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.166017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baumann T, Rottenburger C, Nicolas G, Wild D. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (GEP-NET) - Imaging and staging. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2016;30:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nölting S, Kuttner A, Lauseker M, Vogeser M, Haug A, Herrmann KA, Hoffmann JN, Spitzweg C, Göke B, Auernhammer CJ. Chromogranin a as serum marker for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a single center experience and literature review. Cancers. 2012;4:141–55. doi: 10.3390/cancers4010141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang SC, Parekh JR, Zuraek MB, Venook AP, Bergsland EK, Warren RS, Nakakura EK. Identification of unknown primary tumors in patients with neuroendocrine liver metastases. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill: 1960) 2010;145:276–80. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyubimova NV, Churikova TK, Kushlinskii NE. Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine. Vol. 160. Springer US; 2016. Chromogranin As a Biochemical Marker of Neuroendocrine Tumors; pp. 702–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.