Abstract

Intracellular calcium (Ca2+) signals are key regulators of multiple cellular functions, both healthy and physiopathological. It is therefore unsurprising that several cancers present a strong Ca2+ homeostasis deregulation. Among the various hallmarks of cancer disease, a particular role is played by metastasis, which has a critical impact on cancer patients’ outcome. Importantly, Ca2+ signalling has been reported to control multiple aspects of the adaptive metastatic cancer cell behaviour, including epithelial–mesenchymal transition, cell migration, local invasion and induction of angiogenesis (see Abstract Figure). In this context Ca2+ signalling is considered to be a substantial intracellular tool that regulates the dynamicity and complexity of the metastatic cascade. In the present study we review the spatial and temporal organization of Ca2+ fluxes, as well as the molecular mechanisms involved in metastasis, analysing the key steps which regulate initial tumour spread.

Keywords: calcium channel, calcium signalling, cancer cells

Abbreviations

- AA

arachidonic acid

- EC

endothelial cell

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EMT

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- KCa

Ca2+‐activated potassium channels

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MT1‐MMP

membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase

- MLCK

Ca2+‐dependent myosin light chain kinase

- myo II

myosin II

- NCX

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T‐cells

- ORAI

Ca2+ release‐activated Ca2+ channel protein

- PMCA

plasma membrane ATPase

- SOCE

store‐operated Ca2+ entry

- STIM

stromal interaction molecule

- TEC

tumour‐derived endothelial cell

- TRP

transient receptor potential

- TRPA

transient receptor potential ankyrin channel

- TRPC

transient receptor potential canonical channel

- TRPM

transient receptor potential melastatin channel

- TRPV

transient receptor potential vanilloid channel

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VGCC

voltage‐gated Ca2+ channel

Introduction

Calcium (Ca2+) is a ubiquitous second messenger which is involved in the tuning of multiple fundamental cellular functions (Berridge et al. 2000). Due to its multifaceted roles, it is not surprising that deregulated Ca2+ homeostasis has been observed in various disorders, including tumourigenesis (Monteith et al. 2007; Prevarskaya et al. 2011). Among the various manifestations of cancer, a particular role is played by metastasis, which has a critical impact on cancer patients’ outcome (Hanahan & Weinberg, 2011). Tumour spread is a highly regulated process that usually starts with the loss of cell–cell contact and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Kalluri & Weinberg, 2009). During metastasis, cancer cells also acquire enhanced directional movement and activate molecular pathways that enable the proteolysis of an extracellular matrix (ECM) as well as local angiogenesis. As a result, cancer cells enter the body's circulation systems and disseminate to distinct sites around the organism. Importantly, Ca2+ signalling has been reported to control multiple aspects of the adaptive metastatic cancer cell behaviours, including EMT, migration, local angiogenesis induction and intravasation (Chen et al. 2013). In this context, it is considered to be a substantial intracellular tool that regulates the dynamicity and complexity of the metastatic cascade. Intracellular free Ca2+ concentration is highly controlled by the fine regulation of ‘ON’ and ‘OFF’ mechanisms that ultimately generate Ca2+ signals with various amplitudes and frequencies. As regarding the ON mechanisms, cytosolic Ca2+ can either be delivered from extracellular space due to the activity of Ca2+‐permeable channels and transporters in plasma membrane, or occur as a result of a release from Ca2+‐containing organelles (e.g. endoplasmic reticulum) (Berridge et al. 2000). In order to maintain low resting Ca2+ concentration, cells remove Ca2+ using an energy‐dependent mechanism, such as plasma membrane ATPases (PMCAs), or the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX). Moreover Ca2+ is sequestered intracellularly into Ca2+‐containing organelles, primarily endoplasmic reticulum (ER), by means of mechanisms which require either ATP hydrolysis (e.g. a sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+‐ATPase pump), or a favourable electrochemical gradient. In this review we will overview the spatial and temporal organization of Ca2+ fluxes as well as those molecular mechanisms involved in metastasis, analysing the key steps which regulate tumour spread.

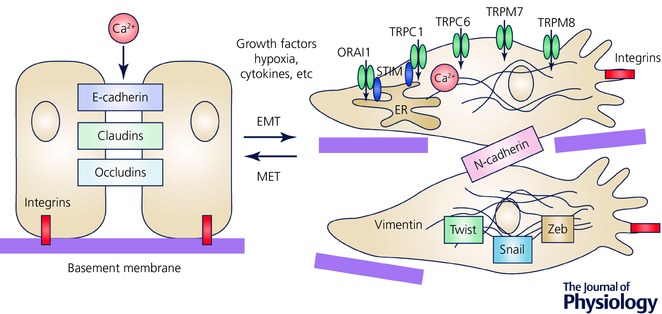

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition and loss of cell–cell contact

EMT is a cellular process during which epithelial cells acquire a fibroblast‐like morphology. This process involves changes in cellular shape, a loss of epithelial polarized organization and cell–cell contacts like tight and adherens junctions. Accordingly, one of the most recognized features of cells undergoing EMT, is a suppression of multiple epithelial markers (e.g. E‐cadherin, claudins, occludins) and an overexpression of mesenchymal markers (e.g. N‐cadherin, vimentin, integrins) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition (EMT), loss of cell–cell contacts and downregulation of proteins such as E‐cadherin, claudin or occludin.

EMT transition is accompanied by the changes in Ca2+ signals due to several factors such as growth factors, cytokines and hypoxia. The most studied Ca2+‐permeable channels, which are associated with EMT, are indicated.

Of note, EMT and the disruption of cell–cell contact is one of the key events in tumour progression. This can be induced by various effectors like growth factors, hypoxia and inflammation (Diepenbruck & Christofori, 2016). Interestingly, the remodelling of Ca2+ signals during EMT processes has been reported for a variety of cancer cells. For example, in breast cancer cells, the potency of ATP‐mediated cytosolic Ca2+ transients exhibits significant changes after epidermal growth factor (EGF) and hypoxia‐induced EMT (Davis et al. 2011; Azimi et al. 2016). Specifically, an attenuation of the cytosolic Ca2+ peak and a sustained phase of Ca2+ influx in the response to ATP have been attributed to the activity of G‐protein‐coupled purinergic receptors (P2Y family) and ligand‐gated Ca2+ channels (P2X family) (Davis et al. 2011; Azimi et al. 2016). Another study reveals that an inhibition of P2X5 reduces the expression of the EMT marker vimentin, whereas its increased expression correlates with breast cancer cells that are associated with a more mesenchymal phenotype (Davis et al. 2011). Moreover, the chelation of free cytosolic Ca2+ suppresses the production of mesenchymal markers like vimentin, N‐cadherin and CD44, after the exposure of breast cancer cells to EGF and hypoxia (Davis et al. 2013; Stewart et al. 2015). Similar findings have been reported for hepatic cancer cells, where chelation of intracellular Ca2+ reversed doxorubicin‐induced EMT (Wen et al. 2016). Furthermore, the EMT of colon cancer cells may be regulated by the small conductance calcium‐activated channel, subfamily N, such as KCNN4, through Ca2+‐dependent mechanisms (Lai et al. 2013). Regarding the store‐operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), the data are ambiguous. On one hand, SOCE and basal Ca2+ influx are reduced after the EGF‐induction of EMT in the MDA‐MD‐468 breast cancer cell line (Davis et al. 2012). On the other hand, transforming growth factor β1 (TGF‐β1)‐induced EMT is associated with enhanced SOCE in the MCF‐7 breast cancer cell line (Hu et al. 2011).

It is now clear that the remodelling of Ca2+ signalling is a prominent feature of EMT in various cancer types. Therefore, a deregulation of Ca2+‐permeable channels could subserve as an important EMT regulator during carcinogenesis. Indeed, silencing and pharmacological inhibition of transient receptor potential melastatin channels (TRPM) such as TRPM7 and TRPM8 reduce the expression of a variety of mesenchymal markers in breast cancer cells (Davis et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2014). In the MCF‐7 breast cancer cell line that exhibits a more epithelial‐like phenotype, the overexpression of TRPM8 leads to EMT induction as indicated by the profile of markers expressed (Liu et al. 2014). Consistent with this data, TRPM8 has been found to be upregulated in breast cancer tumour tissues, when compared to adjacent non‐tumour tissues, thereby suggesting the role of TRPM8 as a determinant of EMT transition (Liu et al. 2014). Moreover, in breast cancer cells, EGF‐induced EMT significantly increases the mRNA level of Ca2+ release‐activated Ca2+ channel protein 1 (ORAI1) and leads to altered Ca2+ signalling, possibly due to the involvement of transient receptor potential canonical channel type 1 (TRPC1) (Davis et al. 2012). In hepatic cancer cells, another member of the transient receptor potential canonical channel family, TRPC6, has been shown to affect the expression of EMT markers after doxorubicin induction (Wen et al. 2016).

Overall, the studies of Ca2+ signalling and Ca2+‐permeable channels using various cancer models and EMT effectors have defined a critical role for the Ca2+ signal in the EMT process during tumourigenesis.

Cell migration

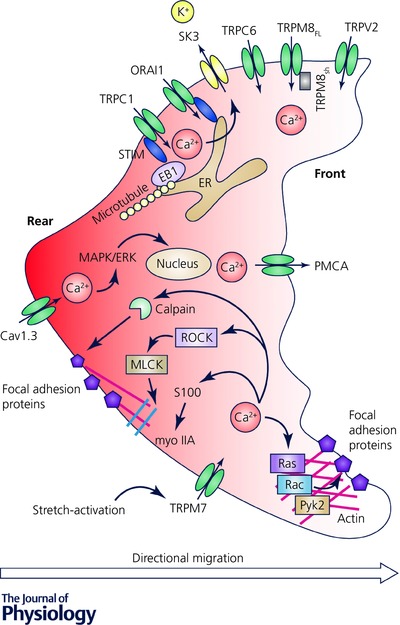

The principal component of cancer cell motility is directional migration, which is due to front–rear end polarity (Mayor & Etienne‐Manneville, 2016). Typically, the leading edge is represented by flat cell membrane extensions with directed actin polymerization and nascent attachment sites, whereas at the rear of the cell, adhesions are disassembled and the trailing edge is contracted (Mayor & Etienne‐Manneville, 2016). Interestingly, global cytosolic Ca2+ is generally higher at the rear end, whereas Ca2+ flickers are enriched near the front edge (Evans et al. 2007; Wei et al. 2009; Tsai & Meyer, 2012). It is suggested that such Ca2+ distribution is involved in controlling directed cellular locomotion (Brundage et al. 1991).

Of note, migration is a complex and multistep process that involves coordination between cytoskeleton remodelling, cell‐substrate adhesion/detachment and cellular protrusion/contraction (Gardel et al. 2010; Parsons et al. 2010). Importantly, several key molecular components and signalling events of the cellular migration machinery are Ca2+ sensitive (Fig. 2). For example, the myosin II (myo II)‐based actomyosin contraction is mainly mediated through the activity of Ca2+‐dependent myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) (Clark et al. 2007). The focal adhesion turnover is also highly dependent on Ca2+ signalling. On the one hand, the disassembly of cell adhesions is achieved due to the cleavage of focal adhesion proteins, such as integrins, talin, vinculin and focal adhesion kinases, by the Ca2+‐sensitive protease, calpain (Franco & Huttenlocher, 2005). On the other hand, Ca2+ is important for the modulation of nascent focal adhesion sites by activating proline‐rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2), and small GTPases like Ras and Rac (Lysechko et al. 2010; Selitrennik & Lev, 2015). S100 proteins, a subgroup of the EF‐hand Ca2+‐binding protein family, regulate a variety of cellular processes via an interaction with different target proteins (Bresnick et al. 2015). In particular, their influence on F‐actin polymerization and myo II–actin assembly has been suggested as governing cell migration due to cytoskeletal structural remodelling (Gross et al. 2014) (Fig. 2). Overall, it is now clear that cell migration can be considered as a Ca2+‐dependent process. Importantly, Ca2+‐permeable channels are responsible for the cytosolic Ca2+ delivery from external and internal cellular stores. Therefore, their activity would define the occurrence of those sustained and transient Ca2+ changes which are important for the orchestration of cellular migration.

Figure 2. Global cytosolic Ca2+ is generally higher at the rear (marked in red), whereas Ca2+ flickers are enriched near the front edge of migrating cell.

The key molecular components and signalling events of the cellular migration machinery are Ca2+ dependent. The most studied Ca2+‐permeable channels, which are associated with directional migration, are indicated. ERK, extracellular signal‐regulated kinase; MAPK, mitogen‐activated protein kinase; MLCK, myosin light chain kinase; Pyk2, proline‐rich tyrosine kinase 2; ROCK, Rho‐associated protein kinase; STIM, stromal interaction molecule.

Interestingly, in migrating erythrocytes and human umbilical vein endothelial cells, the low basal Ca2+ levels at the leading edge are maintained due to the activity of PMCA and the inhibition of PMCA leads to an abrogated front‐to‐rear Ca2+ gradient and decreased migration (Pérez‐Gordones et al. 2009; Tsai et al. 2014). Similar mechanisms could be utilized by the metastatic cells, since the expression of PMCA has been found to directly correlate with the tumourigenicity of breast cancer cells (Lee et al. 2005) (Fig. 2). At the same time, in the front end of ER, low local Ca2+ concentration provokes high sensitivity to SOCE (Tsai et al. 2014). Indeed, the ER residual Ca2+ sensor of SOCE, stromal interaction molecule (STIM), has been found to be distributed along the polar axis in the leading edge of the migrating cell (Tsai et al. 2014). The STIM molecule responds to the ER Ca2+ depletion and provokes ion influx through the plasma membrane ORAI channel (Liou et al. 2005; Roos et al. 2005). Of note, STIM–ORAI proteins have been found to be significantly upregulated in various cancer types and SOCE‐activated Ca2+ signalling is implemented in the mediation of actomyosin assembly and the focal adhesions required for efficient migration (Chen et al. 2011; Fiorio Pla et al. 2016; Jardin & Rosado, 2016) (Fig. 2).

Plasma membrane extensions and protrusions play the role of a mechanical stress and thus provide Ca2+ influx through stretch‐activated channels at the front end of a migrating cell. Indeed, TRPM7 can be activated intracellularly through phospholipase C, or by a membrane stretch (Su et al. 2006; Wei et al. 2009; Gao et al. 2011; Middelbeek et al. 2012). Interestingly, TRPM7 is located in close proximity to calpain and myo II (Clark et al. 2007). Therefore, Ca2+ entry provided through TRPM7 modulates actomyosin cytoskeleton contraction, as well as the dynamics of the focal adhesion turnover required for directional cell migration (Clark et al. 2007). Indeed, the pro‐migratory role of TRPM7 has been demonstrated for breast, lung, pancreatic and nasopharyngeal cancers (Visser et al. 2014). Moreover recently, the mechano‐sensitive TRPC1 activation, located at the rear of the cells, has been shown to play a role in the formation of cell polarity of U2OS bone osteosarcoma cells and their directional migration (Huang et al. 2015). Similarly, several members of the TRP channel family have been implicated in cell migration in various cancer types (Fiorio Pla & Gkika, 2013). In particular most TRP channels have been associated with an increase in migration potential. This is the case for TRPC members such as TRPC1 and TRPC6 in glioma cells (Chigurupati et al. 2010; Bomben et al. 2011). In addition, the vanilloid subfamily TRPV2 has also been associated with increased cellular migration in prostate, bladder and breast cancer (Oulidi et al. 2013; Gambade et al. 2016). In contrast, full length TRPM8, has been reported to inhibit cell migration, thus suggesting a protective role for TRPM8 in prostate metastatic cancer progression (Gkika et al. 2010, 2015), whereas the short TRPM8 isoform could have a pro‐metastatic potential (Peng et al. 2015; Bidaux et al. 2016).

Voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) present another pathway for Ca2+ influx that activates a downstream mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK)–extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK) signalling pathway and increases migration (Mertens‐Walker et al. 2010). In particular, Cav1.3 has been found to be overexpressed in endometrial carcinoma and its knockdown has been shown to reduce migration (Hao et al. 2015). Indeed, at filopodia tips increased Ca2+ concentration provided through L‐type VGCCs directs cancer cell migration due to calpain activation (Jacquemet et al. 2016).

Intracellular Ca2+ is an important regulator of Ca2+‐activated potassium channels (KCa). Furthermore, ORAI and TRPC1 channels may form complexes with small conductance KCa channel SK3 (Chantome et al. 2013; Guéguinou et al. 2016). Such an SK3–ORAI complex is crucial for the migratory function of breast and prostate cancer cells and has been found in bone metastasis (Chantome et al. 2013). Similarly, colon cancer cell migration is dependent on SOCE through the SK3–TRPC1–ORAI1 channel complex (Guéguinou et al. 2016).

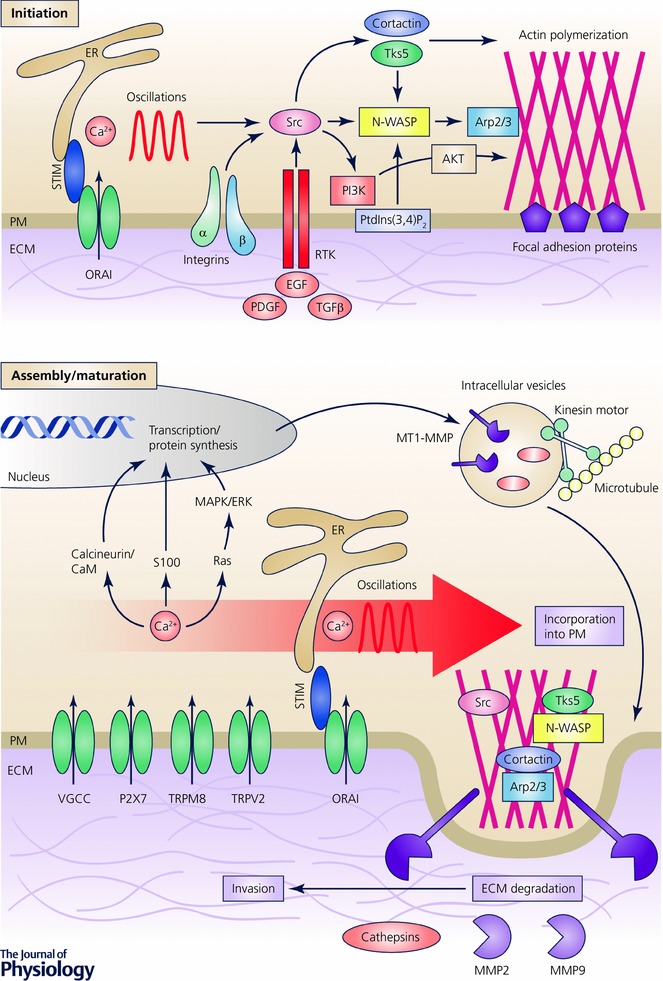

Invasiveness and invadopodia formation

The invasiveness of cancer cells is due to their ability to degrade ECM and migrate into neighbouring connective tissues as well as the lymph‐ and bloodstreams. There, cancer cells spread throughout the organism and give rise to secondary tumour outbursts, metastases. Consequently, the understanding and hence prevention of the process of cancer cell invasion would remarkably improve the survival rate of cancer patients. Cancer cell invasion is achieved due to special structures – invadopodia, which are dynamic actin‐enriched cell protrusions with proteolytic activity. Typically, the invadopodia formation process can be differentiated into the following steps: initiation, assembly and maturation (Fig. 3) (Jacob et al. 2015). The assembly of invadopodia is initiated in response to the focal generation of phosphatidylinositol‐3,4‐bisphosphate and the activation of the non‐receptor tyrosine kinase Src (Mader et al. 2011; Pan et al. 2011; Yamaguchi et al. 2011). The matured invadopodia recruit proteolytic enzymes, such as membrane type 1 (MT1)‐matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), MMP2 and MMP9, to facilitate the focal degradation of the extracellular matrix and allow cell invasion (Beaty et al. 2013).

Figure 3. Ca2+ oscillations are required for the initiation of the invadopodia formation process, whereas Ca2+ influx activates the focal degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM), in particular through upregulation of the proteolytic enzymes like matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and cathepsins.

The most studied Ca2+‐permeable channels, which are associated with invasiveness, are indicated. PI3K, phosphoinositide 3‐kinase; PM, plasma membrane; PtdIns(3,4)P2, phosphatidylinositol‐3,4‐bisphosphate. N‐WASP, neural Wiscott‐Aldrich syndrome protein; PDGF, platelet‐derived growth factor; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase.

Intriguingly, a particular pattern of Ca2+ signalling, Ca2+ oscillations, has been revealed as a predisposing factor for invadopodia formation and activity (Fig. 3) (Sun et al. 2014). For example, Ca2+ oscillations mediated through STIM1 and ORAI1 channels have been reported to activate Src kinase and hence facilitate the assembly of invadopodial precursors in melanoma cells (Sun et al. 2014). The proteolytic activity of invadopodia is predetermined by the incorporation of MMP‐containing endocytic vesicles into the plasma membrane at the ECM degradation sites and can also be linked to Ca2+ signalling machinery (Bravo‐Cordero et al. 2007). Indeed, the inhibition of SOCE‐abrogated fusion of MMP‐containing vesicles with the plasma membrane results in a constrained ECM degradation (Sun et al. 2014). Moreover, constitutively active TRPV2 engenders an intracellular Ca2+ increase and has been associated with an upregulation of MMP9 and the invasive potential of prostate cancer cells (Monet et al. 2010). In oral squamous carcinoma, TRPM8 activity directly correlates with MMP9 activity and the metastatic potential of cells (Okamoto et al. 2012). The downregulation of MMP9 might also be achieved after the inhibition of VGCCs (Kato et al. 2007). Furthermore, in the highly metastatic MDA‐MB‐435 human breast cancer cell line, the activity of the ATP‐gated Ca2+‐permeable P2X7 receptor increases invasion by the release of gelatinolytic cysteine cathepsins (Jelassi et al. 2011). Therefore, in invadopodia, Ca2+ influx is required for the focal degradation of ECM, in particular through the upregulation of proteolytic enzymes like MMPs and cathepsins, whereas Ca2+ oscillations are required for the initiation of the invadopodia formation process (Fig. 3).

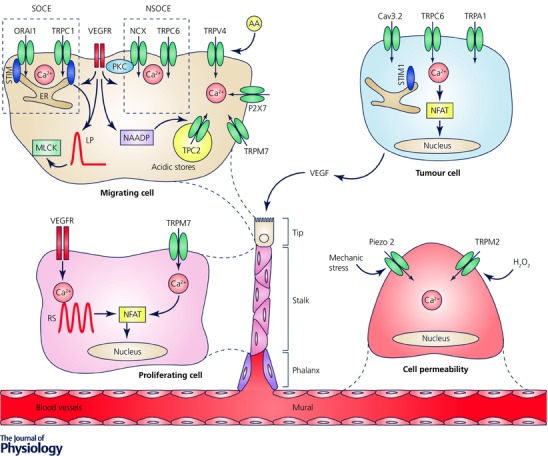

Induction of local angiogenesis

The first mechanical and functional interface between blood and tissues is blood vessels. Thus, in order to sustain metastatic dissemination, as well as providing sufficient metabolic support, tumour neovascularization is required. Indeed, tumour cells enable the ‘activation’ of the nearby endothelial cells (ECs) due to the secretion of specific molecules, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Hence, the complex and multistep process of angiogenesis is achieved due to the proliferation, migration, differentiation and stabilization of such tumour‐derived ECs (TECs) in a new circulatory network (Carmeliet, 2005; Folkman, 2006).

It should be noted that in tumours of various origins, Ca2+ signalling has been shown to regulate the release of VEGF and hence modulate angiogenesis (Fig. 4). For example, plasma membrane Cav3.2 and ER‐residing STIM1 proteins have been shown to promote angiogenesis in vivo due to the stimulation of VEGF secretion in both prostate and cervical cancers (Chen et al. 2011; Warnier et al. 2015). Moreover, the importance of TRPC6 as a modulator of angiogenic potential has been revealed in glioma cells (Chigurupati et al. 2010). According to this study, the number of EC branch points decreases after growing in a conditioned medium harvested from glioma cells, where hypoxia‐induced TRPC6 overexpression and nuclear factor of activated T‐cells (NFAT) activation are inhibited (Chigurupati et al. 2010). Of note, methyl syringate, which is suggested to be a highly specific and selective agonist of transient receptor potential ankyrin channel 1 (TRPA1) suppresses the hypoxia‐induced migration, invasion and secretion of VEGF in human lung epithelial cells (Park et al. 2016).

Figure 4. Induction of local angiogenesis by Ca2+ signalling remodelling.

In tumour cells Ca2+ signals regulate the secretion of proangiogenic stimuli, like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). A newly formed vessel can be differentiated into the following structures: tip – represented by the migrating edge of the vessel; stalk – mostly proliferating part of the vessel; phalanx – tightly apposed, regularly ordered ECs that provide perfusion and oxygenation; mural – functional preformed ECs. Interestingly, VEGF‐ and ATP‐mediated Ca2+ signals provide proangiogenic effects specifically on tumour‐derived tissue and not on healthy ECs. The most studied Ca2+‐permeable channels, which are associated with local angiogenesis, are indicated. NAADP, nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate. LP, long persistent; RS, repeated spikes; NSOCE, non‐store‐operated Ca2+ entry.

Importantly, during tumour neovascularization, the remodelling of Ca2+ machinery has been associated not only with the angiogenic potential of cancer cells, but also with the distinct functions of the ‘activated’ endothelium cells (Fig. 4). Indeed, proangiogenic Ca2+ signals and their related pathways are significantly altered in TECs, compared with normal ECs (Fiorio Pla & Munaron, 2014). As an example, Ca2+ signals mediated by specific factors like VEGF and ATP and intracellular messengers such as arachidonic acid (AA), nitric oxide, or hydrogen sulfide and cyclic AMP are involved in pro‐migratory effects in TEC, but not in normal ECs (Fiorio Pla et al. 2008, 2010, 2012b; Pupo et al. 2011; Avanzato et al. 2016).

Moreover, the role of intracellular Ca2+ increase has been investigated at length in endothelium (Fiorio Pla & Munaron, 2014). Both pro‐ and antiangiogenic molecules can induce an intracellular Ca2+ increase, often leading to different biological effects. For instance, Ca2+ entry triggered by VEGF, as well as by other proangiogenic factors, is often associated with an increase in vessel permeability, EC survival/proliferation, migration and in vitro tubulogenesis (Dragoni et al. 2011, 2015; Li et al. 2011). These outcomes can be achieved by the activation of a distinct intracellular mechanism, such as SOCE via ORAI and TRPC1 channels (Mehta et al. 2003; Paria et al. 2004; Jho et al. 2005; Abdullaev et al. 2008; Dragoni et al. 2011; Li et al. 2011; Fiorio Pla & Munaron, 2014), non‐SOCE mechanisms via TRPC6 channels (Cheng et al. 2006; Hamdollah Zadeh et al. 2008), the specific engagement of the two‐pore channel TPC2 subtype on acidic intracellular Ca2+ stores, resulting in Ca2+ release and angiogenic responses (Favia et al. 2014), or by reverse mode activation of NCX (Fig. 4) (Andrikopoulos et al. 2011). Of note, in a recent study VEGF‐mediated Ca2+ signalling in individual endothelial cells has been investigated and shown to correlate with both stochastic and deterministic response characteristics to the selection of phenotype‐associated angiogenesis. In particular, altering the amount of VEGF signalling in endothelial cells by stimulating them with different VEGF concentrations triggered distinct and mutually exclusive dynamic Ca2+ signalling responses, which correlated with different cellular behaviours such as cell proliferation (monitored by NFAT nuclear translocation) or cell migration (involving MLCK) (Noren et al. 2016). The in vivo role of Ca2+ signals has been recently studied in zebrafish, during angiogenic input by means of high‐speed, three‐dimensional time‐lapse imaging to describe intracellular Ca2+ dynamics in ECs at single‐cell resolution (Yokota et al. 2015; Noren et al. 2016). It may be noted that TRP Ca2+‐permeable channels have profound effects on the control of different steps of tumour angiogenesis. Besides their role in the VEGF‐mediated Ca2+ signals previously described, several data clearly show their involvement Ca2+‐mediated signal transduction with a prominent roles in tumour angiogenesis. In this context, TRPV4 is an emerging player in angiogenesis as on ECs it acts as a mechano‐sensor during changes in cell morphology, cell swelling and shear stress. TRPV4 plays a significant role in endothelial migration, (Fiorio Pla et al. 2012b) displaying a marked increase in ECs derived from human breast carcinomas, as compared with ‘normal’ ECs, leading to a greater Ca2+ entry that in turn activates migration in TECs (Fig. 4) (Fiorio Pla et al. 2012b). Moreover, TRPV4 has recently been described as an important player in tumour vasculature normalization, thereby potentially improving cancer therapies (Adapala et al. 2015; Thoppil et al. 2015, 2016). In addition, TRPM2 has been recently identified as mediating an H2O2‐dependent increase in macrovascular pulmonary EC permeability (Fig. 4) (Hecquet et al. 2008; Mittal et al. 2015). TRPM7 inhibits human umbilical vein endothelial cell proliferation and migration, whereas its functions in human mammary epithelial cells seem to be the opposite (Fig. 4) (Inoue & Xiong, 2009; Baldoli & Maier, 2012; Baldoli et al. 2013; Zeng et al. 2015). Recently, TRPA1 has been found to have a role in the vasodilatation of cerebral arteries, via an increase in Ca2+ influx generated by the detection of reactive oxygen species, a process that requires the peroxidation of membrane lipids (Sullivan et al. 2015). Similarly, TRPV2 has been shown to be expressed in aorta endothelium, but no clear functional data have been reported (Earley, 2011).

Finally, the emerging family of mechanosensitive Piezo channels has recently been described in vascular endothelial cells: Piezo2 knockdown is involved in glioma angiogenesis, both in vitro and in vivo by promoting abnormal intracellular Ca2+, Wnt11/β‐catenin signalling reduction, leading to altered angiogenic activity of endothelial cells (Fig. 4) (Yang et al. 2016).

In conclusion, due to its multifaceted role in the control of endothelium homeostasis, Ca2+ machinery is a potential molecular target for strategies against tumour neovascularization.

Conclusions

A remodelling of Ca2+ signalling plays an important role during tumourigenesis. Interestingly, there are some specific channel patterns through which such Ca2+ signals occur, at the different stages of cancer progression. This could be partially explained by the specificity of Ca2+ flux, its compartment localization and the proximity of downstream Ca2+‐dependent targets. Furthermore, some ion channels represent multimodal activity and are characterized not only as Ca2+‐permeable pore proteins, but also as possessing other functional domains. For example, the C‐terminal end of TRPM7 is constituted by a serine/threonine protein kinase domain and hence, due to the phosphorylation of cytoskeletal components, regulates cellular migration (Clark et al. 2008).

Importantly, plasma membrane Ca2+ channels are easily and directly accessible via the bloodstream. Therefore, they are potential targets for a variety of therapeutic strategies, such as their regulation on a transcriptional and translational level, their trafficking to the plasma membrane or their stabilization at the plasma membrane (Gkika & Prevarskaya, 2009; Fiorio Pla et al. 2012a; Bernardini et al. 2015; Earley & Brayden, 2015).

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions

O.I. and A.F.P. collected information, conceived the concept, prepared figures and drafted the manuscript. N.P. was involved in supervising and editing the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

O.I. was funded by the ‘la Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer’, France (GB/MA/CD 11813) and Laboratory of Excellence in Ion Channel Science and Therapeutics. The work of A.F.P. and N.P. was funded by Institut National du Cancer. The research in the authors' laboratory is supported by INSERM, la Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer, Le Ministere de l'Education Nationale, the Region Nord/Pas‐de‐Calais, la Fondation de Recherche Medicale, and l'Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer.

Biographies

Oksana Iamshanova is a PhD student at the University of Lille 1 (France) in the Laboratory of Cell Physiology headed by Natalia Prevarskaya. Investigating the role of ion channels in tumorigenesis is one of her major research interests.

Alessandra Fiorio Pla is associate professor at the University of Torino (Italy) and visiting professor at the University of Lille 1 (France). Her research activity is focused on Ca2+ channels characterization, in particular TRP channels, and their involvement in angiogenesis and tumour vascularization/progression by combining Ca2+ imaging and live cell imaging techniques with cell biology.

Natalia Prevarskaya is full‐time professor of physiology at the University of Lille 1 (France), director of the Laboratory of Cell Physiology and head of the team ‘Ca2+ signatures of prostate cancer’ certified by the National League Against Cancer. Her scientific interests are the function and regulation of ion channels, the role of ion channels and Ca2+ signalling in carcinogenesis, Ca2+ signalling in proliferation, apoptosis, migration and differentiation, prostate cancer and prostatic diseases.

This review was presented at “Advances and Breakthroughs in Calcium Signaling”, which took place in Honolulu, Hawaii, 7–9 April 2016.

References

- Abdullaev IF, Bisaillon JM, Potier M, Gonzalez JC, Motiani RK & Trebak M (2008). Stim1 and Orai1 mediate CRAC currents and store‐operated calcium entry important for endothelial cell proliferation. Circ Res 103, 1289–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adapala RK, Thoppil RJ, Ghosh K, Cappelli HC, Dudley AC, Paruchuri S, Keshamouni V, Klagsbrun M, Meszaros JG, Chilian WM, Ingber DE & Thodeti CK (2015). Activation of mechanosensitive ion channel TRPV4 normalizes tumor vasculature and improves cancer therapy. Oncogene 35, 314–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrikopoulos P, Baba A, Matsuda T, Djamgoz MBA, Yaqoob MM & Eccles SA (2011). Ca2+ influx through reverse mode Na+/Ca2+ exchange is critical for vascular endothelial growth factor‐mediated extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 activation and angiogenic functions of human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 286, 37919–37931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avanzato D, Genova T, Fiorio Pla A, Bernardini M, Bianco S, Bussolati B, Mancardi D, Giraudo E, Maione F, Cassoni P, Castellano I & Munaron L (2016). Activation of P2X7 and P2Y11 purinergic receptors inhibits migration and normalizes tumor‐derived endothelial cells via cAMP signaling. Sci Rep 6, 32602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azimi I, Beilby H, Davis FM, Marcial DL, Kenny PA, Thompson EW, Roberts‐Thomson SJ & Monteith GR (2016). Altered purinergic receptor‐Ca2+ signaling associated with hypoxia‐induced epithelial‐mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells. Mol Oncol 10, 166–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldoli E, Castiglioni S & Maier JAM (2013). Regulation and function of TRPM7 in human endothelial cells: TRPM7 as a potential novel regulator of endothelial function. PLoS One 8, e59891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldoli E & Maier JAM (2012). Silencing TRPM7 mimics the effects of magnesium deficiency in human microvascular endothelial cells. Angiogenesis 15, 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaty BT, Sharma VP, Bravo‐Cordero JJ, Simpson MA, Eddy RJ, Koleske AJ & Condeelis J (2013). β1 integrin regulates Arg to promote invadopodial maturation and matrix degradation. Mol Biol Cell 24, 1661–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardini M, Fiorio Pla A, Prevarskaya N & Gkika D (2015). Human transient receptor potential (TRP) channel expression profiling in carcinogenesis. Int J Dev Biol 59, 399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Lipp P & Bootman MD (2000). The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 1, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidaux G, Borowiec A‐S, Dubois C, Delcourt P, Schulz C, Vanden Abeele F, Lepage G, Desruelles E, Bokhobza A, Dewailly E, Slomianny C, Roudbaraki M, Héliot L, Bonnal J‐L, Mauroy B, Mariot P, Lemonnier L & Prevarskaya N (2016). Targeting of short TRPM8 isoforms induces 4TM‐TRPM8‐dependent apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Oncotarget 7, 29063–29080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomben VC, Turner KL, Barclay TTC & Sontheimer H (2011). Transient receptor potential canonical channels are essential for chemotactic migration of human malignant gliomas. J Cell Physiol 226, 1879–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo‐Cordero JJ, Marrero‐Diaz R, Megías D, Genís L, García‐Grande A, García MA, Arroyo AG & Montoya MC (2007). MT1‐MMP proinvasive activity is regulated by a novel Rab8‐dependent exocytic pathway. EMBO J 26, 1499–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnick AR, Weber DJ & Zimmer DB (2015). S100 proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 15, 96–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundage RA, Fogarty KE, Tuft RA & Fay FS (1991). Calcium gradients underlying polarization and chemotaxis of eosinophils. Science 254, 703–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P (2005). Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature 438, 932–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantome A, Potier‐Cartereau M, Clarysse L, Fromont G, Marionneau‐Lambot S, Guéguinou M, Pagès JC, Collin C, Oullier T, Girault A, Arbion F, Haelters JP, Jaffrès PA, Pinault M, Besson P, Joulin V, Bougnoux P & Vandier C (2013). Pivotal role of the lipid raft SK3‐orai1 complex in human cancer cell migration and bone metastases. Cancer Res 73, 4852–4861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y‐F, Chen Y‐T, Chiu W‐T & Shen M‐R (2013). Remodeling of calcium signaling in tumor progression. J Biomed Sci 20, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y‐F, Chiu W‐T, Chen Y‐T, Lin P‐Y, Huang H‐J, Chou C‐Y, Chang H‐C, Tang M‐J & Shen M‐R (2011). Calcium store sensor stromal‐interaction molecule 1‐dependent signaling plays an important role in cervical cancer growth, migration, and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 15225–15230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H‐W, James AF, Foster RR, Hancox JC & Bates DO (2006). VEGF activates receptor‐operated cation channels in human microvascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26, 1768–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chigurupati S, Venkataraman R, Barrera D, Naganathan A, Madan M, Paul L, Pattisapu JV, Kyriazis GA, Sugaya K, Bushnev S, Lathia JD, Rich JN & Chan SL (2010). Receptor channel TRPC6 is a key mediator of Notch‐driven glioblastoma growth and invasiveness. Cancer Res 70, 418–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K, Langeslag M, Figdor CG & van Leeuwen FN (2007). Myosin II and mechanotransduction: a balancing act. Trends Cell Biol 17, 178–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K, Middelbeek J, Lasonder E, Dulyaninova NG, Morrice NA, Ryazanov AG, Bresnick AR, Figdor CG & van Leeuwen FN (2008). TRPM7 regulates myosin IIA filament stability and protein localization by heavy chain phosphorylation. J Mol Biol 378, 790–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis F, Azimi I, Faville R, Peters A, Jalink K, Putney J, Goodhill G, Thompson E, Roberts‐Thomson S & Monteith G (2013). Induction of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in breast cancer cells is calcium signal dependent. Oncogene 33, 2307–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis FM, Kenny PA, Soo ETL, van Denderen BJW, Thompson EW, Cabot PJ, Parat MO, Roberts‐Thomson SJ & Monteith GR (2011). Remodeling of purinergic receptor‐mediated Ca2+ signaling as a consequence of EGF‐induced epithelial‐mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells. PLoS One 6, e23464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis FM, Peters AA, Grice DM, Cabot PJ, Parat MO, Roberts‐Thomson SJ & Monteith GR (2012). Non‐stimulated, agonist‐stimulated and store‐operated Ca2+ influx in MDA‐MB‐468 breast cancer cells and the effect of EGF‐induced EMT on calcium entry. PLoS One 7, e36923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diepenbruck M & Christofori G (2016). Epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis: yes, no, maybe? Curr Opin Cell Biol 43, 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragoni S, Pedrazzoli P, Rosti V, Tanzi F & Moccia F (2011). Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates endothelial colony forming cells proliferation and tubulogenesis by inducing oscillations in intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Stem Cells 29, 1898–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragoni S, Reforgiato M, Zuccolo E, Poletto V, Lodola F, Ruffinatti FA, Bonetti E, Guerra G, Barosi G, Rosti V & Moccia F (2015). Dysregulation of VEGF‐induced proangiogenic Ca2+ oscillations in primary myelofibrosis‐derived endothelial colony‐forming cells. Exp Hematol 43, 1019–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley S (2011). Vanilloid and melastatin transient receptor potential channels in vascular smooth muscle. Microcirculation 17, 237–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley S & Brayden JE (2015). Transient receptor potential channels in the vasculature. Physiol Rev 95, 645–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JH, Falke JJ & Mcintosh JR (2007). Ca2+ influx is an essential component of the positive‐feedback loop that maintains leading‐edge structure and activity in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 16176–16181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favia A, Desideri M, Gambara G, Ruas M, Esposito B, Del Bufalo D, Parrington J, Ziparo E, Palombi F, Galione A & Filippini A (2014). VEGF‐induced neoangiogenesis is mediated by NAADP and two‐pore channel‐2‐dependent Ca2+ signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, E4706–E4715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorio Pla A & Munaron L (2014). Functional properties of ion channels and transporters in tumour vascularization. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 369, 20130103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorio Pla A, Avanzato D, Munaron L & Ambudkar IS (2012a). Ion channels and transporters in cancer. 6. Vascularizing the tumor: TRP channels as molecular targets. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 302, C9–C15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorio Pla A, Genova T, Pupo E, Tomatis C, Genazzani A, Zaninetti R & Munaron L (2010). Multiple roles of protein kinase A in arachidonic acid‐mediated Ca2+ entry and tumor‐derived human endothelial cell migration. Mol Cancer Res 8, 1466–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorio Pla A & Gkika D (2013). Emerging role of TRP channels in cell migration: from tumor vascularization to metastasis. Front Physiol 4, 311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorio Pla A, Grange C, Antoniotti S, Tomatis C, Merlino A, Bussolati B & Munaron L (2008). Arachidonic acid‐induced Ca2+ entry is involved in early steps of tumor angiogenesis. Mol Cancer Res 6, 535–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorio Pla A, Kondratska K & Prevarskaya N (2016). STIM and ORAI proteins: crucial roles in hallmarks of cancer. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 310, C509–C519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorio Pla A, Ong HL, Cheng KT, Brossa A, Bussolati B, Lockwich T, Paria B, Munaron L & Ambudkar IS (2012b). TRPV4 mediates tumor‐derived endothelial cell migration via arachidonic acid‐activated actin remodeling. Oncogene 31, 200–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J (2006). Angiogenesis. Annu Rev Med 57, 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco SJ & Huttenlocher A (2005). Regulating cell migration: calpains make the cut. J Cell Sci 118, 3829–3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambade A, Zreika S, Guéguinou M, Chourpa I, Fromont G, Bouchet AM, Burlaud‐Gaillard J, Potier‐Cartereau M, Roger S, Aucagne V, Chevalier S, Vandier C, Goupille C & Weber G (2016). Activation of TRPV2 and BKCa channels by the LL‐37 enantiomers stimulates calcium entry and migration of cancer cells. Oncotarget 7, 23785–23800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Chen X, Du X, Guan B, Liu Y & Zhang H (2011). EGF enhances the migration of cancer cells by up‐regulation of TRPM7. Cell Calcium 50, 559–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardel ML, Schneider IC, Aratyn‐Schaus Y & Waterman CM (2010). Mechanical integration of actin and adhesion dynamics in cell migration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 26, 315–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkika D, Flourakis M, Lemonnier L & Prevarskaya N (2010). PSA reduces prostate cancer cell motility by stimulating TRPM8 activity and plasma membrane expression. Oncogene 29, 4611–4616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkika D, Lemonnier L, Shapovalov G, Gordienko D, Poux C, Bernardini M, Bokhobza A, Bidaux G, Degerny C, Verreman K, Guarmit B, Benahmed M, de Launoit Y, Bindels RJM, Fiorio Pla A & Prevarskaya N (2015). TRP channel‐associated factors are a novel protein family that regulates TRPM8 trafficking and activity. J Cell Biol 208, 89–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkika D & Prevarskaya N (2009). Molecular mechanisms of TRP regulation in tumor growth and metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793, 953–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross SR, Sin CGT, Barraclough R & Rudland PS (2014). Joining S100 proteins and migration: For better or for worse, in sickness and in health. Cell Mol Life Sci 71, 1551–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guéguinou M, Harnois T, Crottes D, Uguen A, Deliot N, Gambade A, Chantôme A, Haelters JP, Jaffrès PA, Jourdan ML, Weber G, Soriani O, Bougnoux P, Mignen O, Bourmeyster N, Constantin B, Lecomte T, Vandier C & Potier‐Cartereau M (2016). SK3/TRPC1/Orai1 complex regulates SOCE‐dependent colon cancer cell migration: a novel opportunity to modulate anti‐EGFR mAb action by the alkyl‐lipid Ohmline. Oncotarget 7, 36168–36184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdollah Zadeh MA, Glass CA, Magnussen A, Hancox JC & Bates DO (2008). VEGF‐mediated elevated intracellular calcium and angiogenesis in human microvascular endothelial cells in vitro are inhibited by dominant negative TRPC6. Microcirculation 15, 605–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D & Weinberg RA (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J, Bao X, Jin B, Wang X, Mao Z, Li X, Wei L, Shen D & Wang J‐L (2015). Ca2+ channel subunit a 1D promotes proliferation and migration of endometrial cancer cells mediated by 17b‐estradiol via the G protein‐coupled estrogen receptor. FASEB J 29, 2883–2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecquet CM, Ahmmed GU, Vogel SM & Malik AB (2008). Role of TRPM2 channel in mediating H2O2‐induced Ca2+ entry and endothelial hyperpermeability. Circ Res 102, 347–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Qin K, Zhang Y, Gong J, Li N, Lv D, Xiang R & Tan X (2011). Downregulation of transcription factor Oct4 induces an epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition via enhancement of Ca2+ influx in breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 411, 786–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Chang S, I‐Chen Harn H, Huang H, Lin H, Shen M, Tang M & Chiu W (2015). Mechanosensitive store‐ operated calcium entry regulates the formation of cell polarity. J Cell Physiol 230, 2086–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K & Xiong ZG (2009). Silencing TRPM7 promotes growth/proliferation and nitric oxide production of vascular endothelial cells via the ERK pathway. Cardiovasc Res 83, 547–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob A, Prekeris R, Kaverina I & Roger S (2015). The regulation of MMP targeting to invadopodia during cancer metastasis. Front Cell Dev Biol 3, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemet G, Baghirov H, Georgiadou M, Sihto H, Peuhu E, Cettour‐Janet P, He T, Perälä M, Kronqvist P, Joensuu H & Ivaska J (2016). L‐type calcium channels regulate filopodia stability and cancer cell invasion downstream of integrin signalling. Nat Commun 7, 13297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardin I & Rosado JA (2016). STIM and calcium channel complexes in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1863, 1418–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelassi B, Chantoe A, Alcaraz‐Peez F, Baroja‐Mazo A, Cayuela M, Pelegrin P, Surprenant A & Roger S (2011). P2X7 receptor activation enhances SK3 channels‐ and cystein cathepsin‐dependent cancer cells invasiveness. Oncogene 30, 2108–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jho D, Mehta D, Ahmmed G, Gao X‐P, Tiruppathi C, Broman M & Malik AB (2005). Angiopoietin‐1 opposes VEGF‐induced increase in endothelial permeability by inhibiting TRPC1‐dependent Ca2+ influx. Circ Res 96, 1282–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R & Weinberg RA (2009). The basics of epithelial‐mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 119, 1420–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Ozawa S, Tsukuda M, Kubota E, Miyazaki K, St‐Pierre Y & Hata RI (2007). Acidic extracellular pH increases calcium influx‐triggered phospholipase D activity along with acidic sphingomyelinase activation to induce matrix metalloproteinase‐9 expression in mouse metastatic melanoma. FEBS J 274, 3171–3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai W, Liu L, Zeng Y, Wu H, Xu H, Chen S & Chu Z (2013). KCNN4 channels participate in the EMT induced by PRL‐3 in colorectal cancer. Med Oncol 30, 566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WJ, Roberts‐Thomson SJ & Monteith GR (2005). Plasma membrane calcium‐ATPase 2 and 4 in human breast cancer cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 337, 779–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Cubbon RM, Wilson LA, Amer MS, McKeown L, Hou B, Majeed Y, Tumova S, Seymour VAL, Taylor H, Stacey M, O'Regan D, Foster R, Porter KE, Kearney MT & Beech DJ (2011). Orai1 and CRAC channel dependence of VEGF‐activated Ca2+ entry and endothelial tube formation. Circ Res 108, 1190–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J, Kim ML, Won DH, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE & Meyer T (2005). STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+‐store‐ depletion‐triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol 15, 1235–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Chen Y, Shuai S, Ding D, Li R & Luo R (2014). TRPM8 promotes aggressiveness of breast cancer cells by regulating EMT via activating AKT/GSK‐3β pathway. Tumor Biol 35, 8969–8977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysechko TL, Cheung SMS & Ostergaard HL (2010). Regulation of the tyrosine kinase Pyk2 by calcium is through production of reactive oxygen species in cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem 285, 31174–31184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mader CC, Oser M, Magalhaes MAO, Bravo‐Cordero JJ, Condeelis J, Koleske AJ & Gil‐Henn H (2011). An EGFR‐Src‐Arg‐cortactin pathway mediates functional maturation of invadopodia and breast cancer cell invasion. Cancer Res 71, 1730–1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor R & Etienne‐Manneville S (2016). The front and rear of collective cell migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17, 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta D, Ahmmed GU, Paria BC, Holinstat M, Voyno‐Yasenetskaya T, Tiruppathi C, Minshall RD & Malik AB (2003). RhoA interaction with inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate receptor and transient receptor potential channel‐1 regulates Ca2+ entry. Role in signaling increased endothelial permeability. J Biol Chem 278, 33492–33500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens‐Walker I, Bolitho C, Baxter RC & Marsh DJ (2010). Gonadotropin‐induced ovarian cancer cell migration and proliferation require extracellular signal‐regulated kinase 1/2 activation regulated by calcium and protein kinase Cd. Endocr Relat Cancer 17, 335–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelbeek J, Kuipers AJ, Henneman L, Visser D, Eidhof I, Van Horssen R, Wieringa B, Canisius SV, Zwart W, Wessels LF, Sweep FCGJ, Bult P, Span PN, Van Leeuwen FN & Jalink K (2012). TRPM7 is required for breast tumor cell metastasis. Cancer Res 72, 4250–4561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal M, Urao N, Hecquet CM, Zhang M, Sudhahar V, Gao X, Komarova Y, Ushio‐Fukai M & Malik AB (2015). Novel role of reactive oxygen species‐activated trp melastatin channel‐2 in mediating angiogenesis and postischemic neovascularization significance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35, 877–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monet M, Lehen'kyi V, Gackiere F, Firlej V, Vandenberghe M, Roudbaraki M, Gkika D, Pourtier A, Bidaux G, Slomianny C, Delcourt P, Rassendren F, Bergerat JP, Ceraline J, Cabon F, Humez S & Prevarskaya N (2010). Role of cationic channel TRPV2 in promoting prostate cancer migration and progression to androgen resistance. Cancer Res 70, 1225–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteith GR, McAndrew D, Faddy HM & Roberts‐Thomson SJ (2007). Calcium and cancer: targeting Ca2+ transport. Nat Rev Cancer 7, 519–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noren DP, Chou WH, Lee SH, Qutub AA, Warmflash A, Wagner DS, Popel AS & Levchenko A (2016). Endothelial cells decode VEGF‐mediated Ca2+ signaling patterns to produce distinct functional responses. Sci Signal 9, ra20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto Y, Ohkubo T, Ikebe T & Yamazaki J (2012). Blockade of TRPM8 activity reduces the invasion potential of oral squamous carcinoma cell lines. Int J Oncol 40, 1431–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oulidi A, Bokhobza A, Gkika D, Vanden Abeele F, Lehen'kyi V, Ouafik L, Mauroy B & Prevarskaya N (2013). TRPV2 mediates adrenomedullin stimulation of prostate and urothelial cancer cell adhesion, migration and invasion. PLoS One 8, e64885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan YR, Chen CL & Chen HC (2011). FAK is required for the assembly of podosome rosettes. J Cell Biol 195, 113–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paria BC, Vogel SM, Ahmmed GU, Alamgir S, Shroff J, Malik AB, Tiruppathi C & Biman C (2004). Tumor necrosis factor‐induced TRPC1 expression amplifies store‐operated Ca2+ influx and endothelial permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 287, L1303–L1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Shim MK, Jin M, Rhyu MR & Lee YJ (2016). Methyl syringate, a TRPA1 agonist represses hypoxia‐induced cyclooxygenase‐2 in lung cancer cells. Phytomedicine 23, 324–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Rick Horwitz A & Schwartz MA (2010). Cell adhesion: integrating cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular tension. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11, 633–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng M, Wang Z, Yang Z, Tao L, Liu Q, Yi L & Wang X (2015). Overexpression of short TRPM8 variantα promotes cell migration and invasion, and decreases starvation‐induced apoptosis in prostate cancer LNCaP cells. Oncol Lett 10, 1378–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Gordones MC, Lugo MR, Winkler M, Cervino V & Benaim G (2009). Diacylglycerol regulates the plasma membrane calcium pump from human erythrocytes by direct interaction. Arch Biochem Biophys 489, 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevarskaya N, Skryma R & Shuba Y (2011). Calcium in tumour metastasis: new roles for known actors. Nat Rev Cancer 11, 609–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pupo E, Fiorio Pla A, Avanzato D, Moccia F, Avelino Cruz JE, Tanzi F, Merlino A, Mancardi D & Munaron L (2011). Hydrogen sulfide promotes calcium signals and migration in tumor‐derived endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med 51, 1765–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, Veliçelebi G & Stauderman KA (2005). STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store‐operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol 169, 435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selitrennik M & Lev S (2015). PYK2 integrates growth factor and cytokine receptors signaling and potentiates breast cancer invasion via a positive feedback loop. Oncotarget 6, 22214–22226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart TA, Azimi I, Thompson EW, Roberts‐Thomson SJ & Monteith GR (2015). A role for calcium in the regulation of ATP‐binding cassette, sub‐family C, member 3 (ABCC3) gene expression in a model of epidermal growth factor‐mediated breast cancer epithelial‐mesenchymal transition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 458, 509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su LT, Agapito MA, Li M, Simonson WTN, Huttenlocher A, Habas R, Yue L & Runnels LW (2006). TRPM7 regulates cell adhesion by controlling the calcium‐dependent protease calpain. J Biol Chem 281, 11260–11270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MN, Gonzales AL, Pires PW, Bruhl A, Leo MD, Li W, Oulidi A, Boop FA, Feng Y, Jaggar JH, Welsh DG & Earley S (2015). Localized TRPA1 channel Ca2+ signals stimulated by reactive oxygen species promote cerebral artery dilation. Sci Signal 8, ra2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Lu F, He H, Shen J, Messina J, Mathew R, Wang D, Sarnaik AA, Chang WC, Kim M, Cheng H & Yang S (2014). STIM1‐ and Orai1‐mediated Ca2+ oscillation orchestrates invadopodium formation and melanoma invasion. J Cell Biol 207, 535–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoppil RJ, Adapala RK, Cappelli HC, Kondeti V, Dudley AC, Gary Meszaros J, Paruchuri S & Thodeti CK (2015). TRPV4 channel activation selectively inhibits tumor endothelial cell proliferation. Sci Rep 5, 14257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoppil RJ, Cappelli HC, Adapala RK, Kanugula AK, Paruchuri S & Thodeti CK (2016). TRPV4 channels regulate tumor angiogenesis via modulation of Rho/Rho kinase pathway. Oncotarget 7, 25849–25861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai FC & Meyer T (2012). Ca2+ pulses control local cycles of lamellipodia retraction and adhesion along the front of migrating cells. Curr Biol 22, 837–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai F‐C, Seki A, Yang HW, Hayer A, Carrasco S, Malmersjö S & Meyer T (2014). A polarized Ca2+, diacylglycerol and STIM1 signalling system regulates directed cell migration. Nat Cell Biol 16, 133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser D, Middelbeek J, Van Leeuwen FN & Jalink K (2014). Function and regulation of the channel‐kinase TRPM7 in health and disease. Eur J Cell Biol 93, 455–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnier M, Roudbaraki M, Derouiche S, Delcourt P, Bokhobza A, Prevarskaya N & Mariot P (2015). CACNA2D2 promotes tumorigenesis by stimulating cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Oncogene 34, 5383–5394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C, Wang X, Chen M, Ouyang K, Song L‐S & Cheng H (2009). Calcium flickers steer cell migration. Nature 457, 901–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen L, Liang C, Chen E, Chen W, Liang F, Zhi X, Wei T, Xue F, Li G, Yang Q, Gong W, Feng X, Bai X & Liang T (2016). Regulation of Multi‐drug Resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cells is TRPC6/Calcium Dependent Sci Rep 6, 23269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Yoshida S, Muroi E, Yoshida N, Kawamura M, Kouchi Z, Nakamura Y, Sakai R & Fukami K (2011). Phosphoinositide 3‐kinase signaling pathway mediated by p110α regulates invadopodia formation. J Cell Biol 193, 1275–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Liu C, Zhou R‐M, Yao J, Li X‐M, Shen Y, Cheng H, Yuan J, Yan B & Jiang Q (2016). Piezo2 protein: a novel regulator of tumor angiogenesis and hyperpermeability. Oncotarget 7, 44630–44643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota Y, Nakajima H, Wakayama Y, Muto A, Kawakami K, Fukuhara S & Mochizuki N (2015). Endothelial Ca2+ oscillations reflect VEGFR signaling‐regulated angiogenic capacity in vivo. Elife 4, e08817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z, Inoue K, Sun H, Leng T, Feng X, Zhu L & Xiong Z‐G (2015). TRPM7 regulates vascular endothelial cell adhesion and tube formation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 308, C308–C318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]