Abstract

The complexity change of brain activity in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an interesting topic for clinical purpose. To investigate the dynamical complexity of brain activity in AD, a multivariate multi-scale weighted permutation entropy (MMSWPE) method is proposed to measure the complexity of electroencephalograph (EEG) obtained in AD patients. MMSWPE combines the weighted permutation entropy and the multivariate multi-scale method. It is able to quantify not only the characteristics of different brain regions and multiple time scales but also the amplitude information contained in the multichannel EEG signals simultaneously. The effectiveness of the proposed method is verified by both the simulated chaotic signals and EEG recordings of AD patients. The simulation results from the Lorenz system indicate that MMSWPE has the ability to distinguish the multivariate signals with different complexity. In addition, the EEG analysis results show that in contrast with the normal group, the significantly decreased complexity of AD patients is distributed in the temporal and occipitoparietal regions for the theta and the alpha bands, and also distributed from the right frontal to the left occipitoparietal region for the theta, the alpha and the beta bands at each time scale, which may be attributed to the brain dysfunction. Therefore, it suggests that the MMSWPE method may be a promising method to reveal dynamic changes in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Electroencephalograph, Complexity, Weighted permutation entropy, Multivariate multi-scale entropy

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is considered to be the most common type of dementia, which affects millions of elderly people around the world. This progressive disease is characterized by senile or neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the medial temporal lobe structures and cortical areas of the brain, together with a degeneration of the neurons and synapses (Mattson 2004; Blennow et al. 2006). Since AD is a cortical dementia, the electroencephalogram (EEG) which reflects the functional changes in the cerebral cortex is becoming a useful tool for the study of AD (Dauwels et al. 2010a, b; Laske et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2016). The most frequently observed abnormalities in AD are characterized by the perturbations in EEG synchrony (Dauwels et al. 2010a, b; Wang et al. 2015), slowing of the EEG (Czigler et al. 2008; Moretti et al. 2009) and reduced complexity of the EEG signals (Abásolo et al. 2005, 2006, 2008; Park et al. 2007; Woon et al. 2007). Besides, the relation between the above characteristics have also been investigated in some works (Dauwels et al. 2011).

Many complexity measures have been applied to track the pathological alteration of brain with neurological disorders or doing specific tasks, including fractal dimension, Lempel–Ziv complexity, and entropic approaches, which are capable of measuring the probability distributions of possible state and revealing the complexity of the system (Başar et al. 2012; Cao et al. 2015; Hemmati et al. 2013; Talebi et al. 2012). Recently, permutation entropy (PE) (Bandt and Pompe 2002) to characterize the complexity of time series is attracting widespread interests. Many studies indicate the effectiveness of PE in different branches of brain activity study, such as epilepsy research (Bruzzo et al. 2008; Cao et al. 2004; Li et al. 2007; Ouyang et al. 2009, 2010), anesthesiology (Li et al. 2008; Olofsen et al. 2008) and cognitive neuroscience (Schinkel et al. 2007, 2009). Besides, some research works also suggest that PE could be a useful tool for AD detection (Morabito et al. 2012; Timothy et al. 2014). Considering the slowing of EEG in AD reflected in the EEG spectrum (Baker et al. 2008; Morabito et al. 2012; van der Hiele et al. 2007), the information contained in the amplitude of EEG is important for the study of AD. However, PE neglects the influence of the amplitude information and could not differentiate between distinct patterns of a certain motif.

Weighted-permutation entropy (WPE) proposed by Bilal Fadlallah et al. (2013) addressed the limitation of PE. It is modified from PE and incorporates the amplitude information between neighboring values by assigning weights for each vectors extracted from a given signal. Bilal Fadlallah et al. (2013) applied WPE for epilepsy detection and achieved better discriminability than PE. Our previous study (Deng et al. 2015) also showed that WPE can exhibit a better performance in distinguishing the AD patients from the normal controls. However, the quantification of the regularity of a time series on a single time scale based on the traditional entropic methods including WPE may lead to spurious results for nonlinear time series. This can be attributed to the fact that the time series recorded from dynamical physiological systems generally exhibit long-range correlations at multiple temporal scales (Costa et al. 2002) and the complexity of the time series characterized by the entropic values appears different trends with the increase of time scale. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the entropy values at multiple temporal scales. Costa et al. proposed the multi-scale entropy (MSE) and several studies (Escudero et al. 2006; Yang et al. 2013) have supported the effective application of MSE to the analysis of AD. Moreover, WPE algorithm designed for single channel time series is not suitable for multivariate cases, because it deals with the multivariate time series of the complex systems separately and neglects the correlations between different channels, while the correlating effect in the lobe level introduced by the volume conduction should not be neglected.

An original multivariate multi-scale methodology for assessing the complexity of physiological signals was proposed by Ahmed and Mandic (2012) in order to account for both within- and cross-channel dependencies in multiple data channels. The approach combines the univariate MSE and the multivariate cases. It has been validated on both synthetic data and on real-world multivariate physiological data. Morabito et al. (2012) also noticed that the EEG is a multivariate, correlated and noisy data, and they proposed multivariate multi-scale permutation entropy (MMSPE) method. MMSPE was applied to the complexity analysis of EEG in AD and it has the capability of distinguishing AD patients from the normal controls. However, their conclusions are supported by a very small database and are lack of statistical validation. Besides, the behavior of MMSPE has not been testified on any simulated data to ensure its advantage on dealing with the multivariate multi-scale case.

Considering the above factors, a multivariate multi-scale weighted permutation entropy (MMSWPE) is proposed to detect the complexity abnormality of AD EEG at rest state. This method takes into account the permutation patterns incorporating the amplitude information and the correlations between different temporal scales and different brain regions. Firstly, the performance of MMSWPE is validated on the synthetic data, and then the method is applied to extract the complexity features of AD patients and the normal controls in different EEG frequency bands. The remaining part of this paper is organized as follows: in second section, the “Experiment design and EEG recordings” are briefly introduced, including the subjects, the EEG recordings and data preprocessing; in “Methods” section, a description of MMSWPE is presented; in “Results” section, the effectiveness of MMSWPE is verified by the simulated signals, and the advantage of MMSWPE over MMSPE is confirmed by the experimental signals, besides, the MMSWPE analysis results of AD are presented; which is followed by “Discussion” in section seven and “Conclusion” in section eight.

Experiment design and EEG recording

Subjects

The experimental subjects consisted of 14 right-handed AD patients and 14 age-matched normal controls. All the patients (six males and eight females, age 74–78 years old) fulfilled the criteria of probable AD and had undergone thorough clinical examinations, including clinical history, physical and neurological examinations, computed tomography (CT), structural MRI and Mini-Mental-Status examination. The Mini-Mental-Status examination (MMSE) scores ranged from 12 to 15, which indicated a severe cognitive impairment. The control group was formed by four males and ten females (age 74–78 years old) that had no past or present neurological disorders and were not abusing alcohol or illicit drugs which may affect EEG activity. The MMSE scores for all control subjects ranged from 28 to 30. Our study was approved by the local ethics committee. All the subjects gave their informed consent for participation in the current study.

EEG recordings and preprocessing

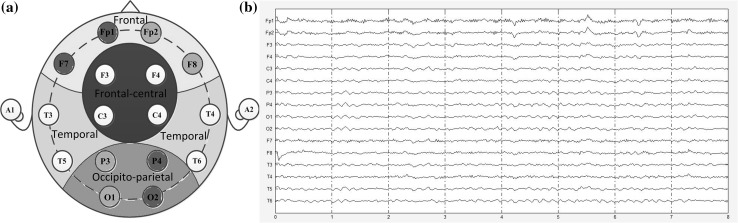

The EEG data were recorded from each subject by a 16-channel Symtop system which is widely used for clinical settings and research purposes at electrodes Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, C3, C4, P3, P4, O1, O2, F7, F8, T3, T4, T5 and T6 of the international 10–20 system, as is shown in Fig. 1a. The linked ears A1 and A2 were used as a reference. In order to detect the difference among different brain regions, we categorize the EEG electrodes according to their positions, namely, frontal (F7, Fp1, Fp2, F8), frontal-central (F3, F4, C3, C4), temporal (T3, T4, T5, T6), occipitoparietal (O1, O2, P3, P4) (Bjørk et al. 2009), left frontal-right occipitoparietal (F7, Fp1, P4, O2) and right frontal-left occipitoparietal (Fp2, F8, P3, O1). The sampling frequency is 1024 Hz. About 5 min of EEG recordings are collected from the subjects whose eyes are closed in a relaxed state with a low level of environmental noise. During the experiment, all the subjects were seated upright in a dedicated semi-dark quiet room which was electromagnetic shielded. All the subjects were told to minimize their movements in order to obtain artifact-free EEG data. The sample selected from the EEG recordings is shown in Fig. 1b.

Fig. 1.

The brain regions and the EEG recordings. a Electrodes position and brain regions. The placement of the electrodes is according to the international 10–20 system. There are six brain regions marked with different colors: the frontal region (Fp1, Fp2, F7, F8) is marked with yellow shade, the frontal-central region (F3, F4, C3, C4) is marked with red shade, the temporal region (T3, T4, T5, T6) is marked with green shade, the occipitoparietal region (O1, O2, P3, P4) is marked with blue shade, the left frontal to the right occipitoparietal region (F7, Fp1, P4, O2) is marked with purple shade and the right frontal to the left occipitoparietal region (Fp2, F8, P3, O1) is marked with pink shade. b 16-channel EEG signals recorded for one AD patient. (Color figure online)

The raw multichannel EEG data for each subject are segmented into 5 non-overlapping eight-second epochs using the EEGLAB toolbox to achieve high confidence of the data. Besides, the artifacts caused by eye movement, muscular movement or other visible disturbances were removed manually on the basis of a thorough visual inspection. The complexity analysis was performed on the following frequency bands: the delta (0.5–4 Hz), the theta (4–8 Hz), the alpha (8–15 Hz) and the beta (16–30 Hz) rhythms. The band-passed Finite Impulse Response (FIR) filter was used to divide the EEG signals into those sub-bands. The digitized EEG data are processed in MATLAB environment (R2014a).

Method

PE and WPE

For an N-point time series , a set of m-dimensional vectors are formed as with ranged from 1 to . Next, arrange in the incremental order , and define as the ordinal pattern. There will be possible ordinal patterns (also called motifs) for -dimensional space and each vector in m-dimensional space can be mapped to one of the motifs. Let represent the frequency of occurrence for each motif in the time series. The probability distribution for each motif is indicated as

| 1 |

where . Then the PE for time series is defined as follows:

| 2 |

The main drawback of PE is that the generation of ordinal patterns maintains little amplitude information, which leads to the vectors with different amplitude distributions contribute similarly to the estimation of PE. Meanwhile, treating the effects of noise uniformly on the PE value leads to the inaccurate ordinal patterns. Consequently, Fadlallah et al. (2013) proposed the weighted-permutation entropy (WPE), which incorporates amplitude information of the time series. The difference between PE and WPE depends on the calculating of the probability distribution of a motif. In order to illustrate the difference, we give an alternative description of as follows:

| 3 |

where , denotes the indicator function of set A defined as if and if .

For WPE, the probability distribution of each motif is defined as follows:

| 4 |

where is the weighted value for vector and is calculated by the variance of each adjacent vector . The expression is

| 5 |

where denotes the arithmetic mean of .

WPE is the extension of PE, and it saves useful amplitude information included in the signal, which is computed as,

| 6 |

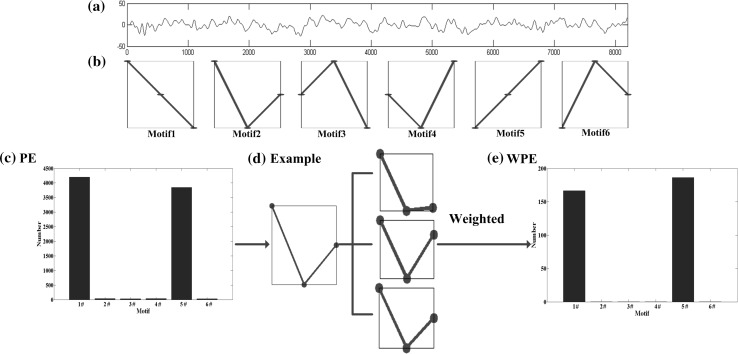

The calculation of is equivalent to the feature selection from the signals. A pictorial description of the PE and the WPE is given in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Illustrations of PE and WPE. a An 8 s segment sample EEG recording extracted from the database. b The six possible motifs corresponding to the embedding dimension and the time delay . c The absolute frequency distribution of the six motifs for PE. d An example of possible vectors corresponding to the same motif. e The absolute frequency distribution of the six motifs for WPE

Multi-scale measures

Given an original time series , a “coarse-graining” process is applied by averaging the time data points within non-overlapping time slice of increasing length , which is defined as the time scale factor. The original time series is then converted into successive coarse-grained versions. Each element of the coarse-grained time series, is computed as:

| 7 |

Multivariate analysis

This method refers to Keller and Wittfeld (2004) and Labate et al. (2013). Given the multiple-channel EEG recordings, a time window of length (data points) and width (channels) is used to select the EEG data, then the absolute frequency is calculated for each channel and for each motif . A matrix of rows and columns reflects the distribution of the motifs in the time window of length . The relative frequency of each channel and each motif is obtained by using the absolute frequency divided by the sum of the matrix. The marginal relative frequencies of each motif is expressed as

| 8 |

The multivariate WPE (MWPE) indicating the cross-channels complexity is calculated as

| 9 |

The single channel WPE can be calculated by the same matrix as follows:

| 10 |

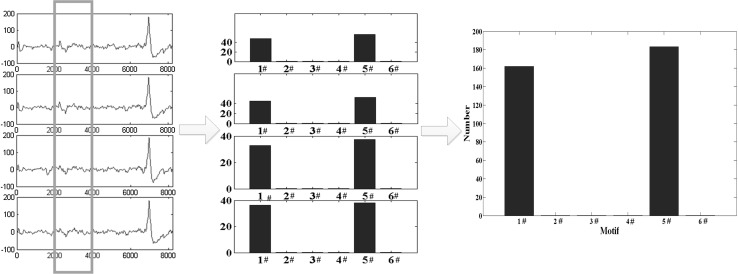

In order to explain the MWPE visually, a pictorial representation of the MWPE is shown in Fig. 3. Four different EEG channels and their absolute frequency of each motif are shown. The right one is the multivariate absolute frequency of each motif.

Fig. 3.

A pictorial representation of the multivariate WPE (MWPE). Four channels and the absolute frequency distributions of the six motifs are given. The right one is the multivariate motifs distribution

The multivariate multi-scale weighted permutation entropy

In order to extract the complexity of AD more effectively, the WPE and the multivariate multi-scale method are combined and multivariate multi-scale weighted permutation entropy (MMSWPE) method is proposed. For an -channel EEG recordings (data points), and , the MMSWPE algorithm is implemented according to the two following steps

- Different time scales of increasing length are obtained by coarse-graining the original multivariate EEG recordings. For a scale factor , the elements of the multivariate coarse-grained EEG recordings is derived as:

11 Calculate MWPE for each coarse-grained multivariate , and plot MWPE as a function of the scale factor .

If the second step is to calculate the multivariate PE for each coarse-grained multivariate , then the analysis results are the multivariate multi-scale permutation entropy (MMSPE) (Labate et al. 2013).

Results

The performance of MMSWPE method is validated with the synthetic data including different types of noise signals and chaotic signals generated by the Lorentz system firstly. In order to confirm the advantage of MMSWPE, the behavior of MMSWPE and MMSPE is then compared for the complexity analysis of EEG. Finally, the method is applied for AD detection.

Validation on synthetic data

Considering the fact that MMSWPE combines WPE and the multivariate multi-scale method, the performance of WPE, multi-scale WPE and MMSWPE are validated step by step.

The chaotic signals are generated by the Lorentz system to make a comparison between WPE and PE. The Lorentz system can be defined by the following set of equations (Lorenz 1963):

| 12 |

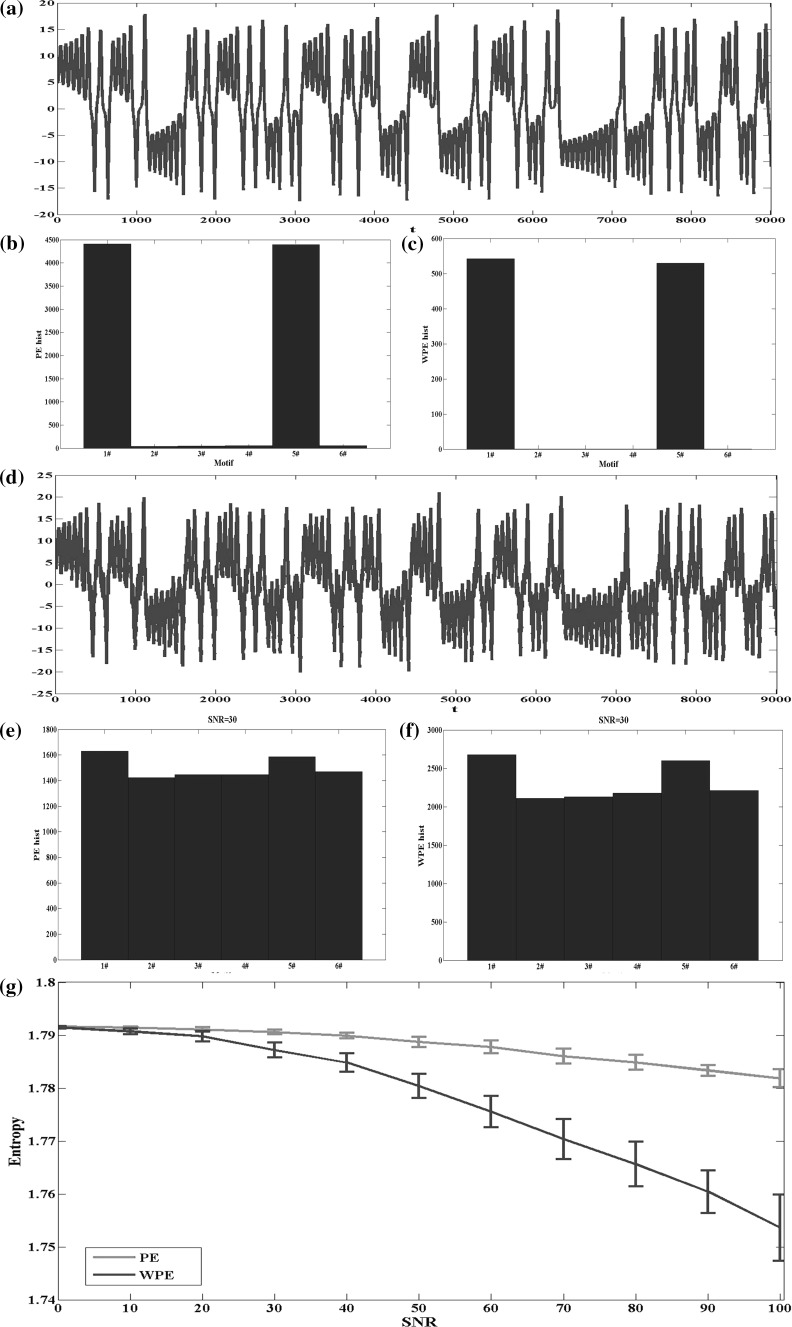

where and is chosen to satisfy the chaotic condition. Variable generated from the system is shown in Fig. 4a, and the corresponding absolute frequency of each motif of PE and WPE are shown in Fig. 4b, c, respectively. The values of the parameters used to calculate WPE and PE in this section are m = 3 and τ = 1 (Bandt and Pompe 2002). Then the white noise is added to the synthetic signal with the signal to noise ratio (SNR) = 30, which is shown in Fig. 4d. Compare the difference of the absolute frequency between PE and WPE in Fig. 4e, f, and it is found that the number of each motif of WPE increases less than that of PE with noise interference. Next the SNR is changed from 0 to 100 and 10 realizations of the chaotic signals are generated by the Lorenz system for each SNR level. The WPE drops dramatically with the increase of SNR, while PE decreases at a smaller pace than WPE in Fig. 4g. The complexity of the useful signal with different intensity of the noise can be discriminated by WPE values more effectively.

Fig. 4.

Comparison between WPE and PE on the chaotic signals generated by the Lorentz system. a A sample chaotic signal generated by the Lorentz system. b PE absolute frequency of the six possible motifs () for the signal in a. c WPE absolute frequency of the six possible motifs () for the signal in a. d The chaotic signal in a added with the white noise (). e PE absolute frequency of the six possible motifs () for the signal in d. f WPE absolute frequency of the six possible motifs () for the signal in d. g WPE and PE values of the chaotic signals, and with additive Gaussian noise of different SNR level. Lines represent the mean value of entropies over 10 realizations for each SNR level, and bars represent the SD

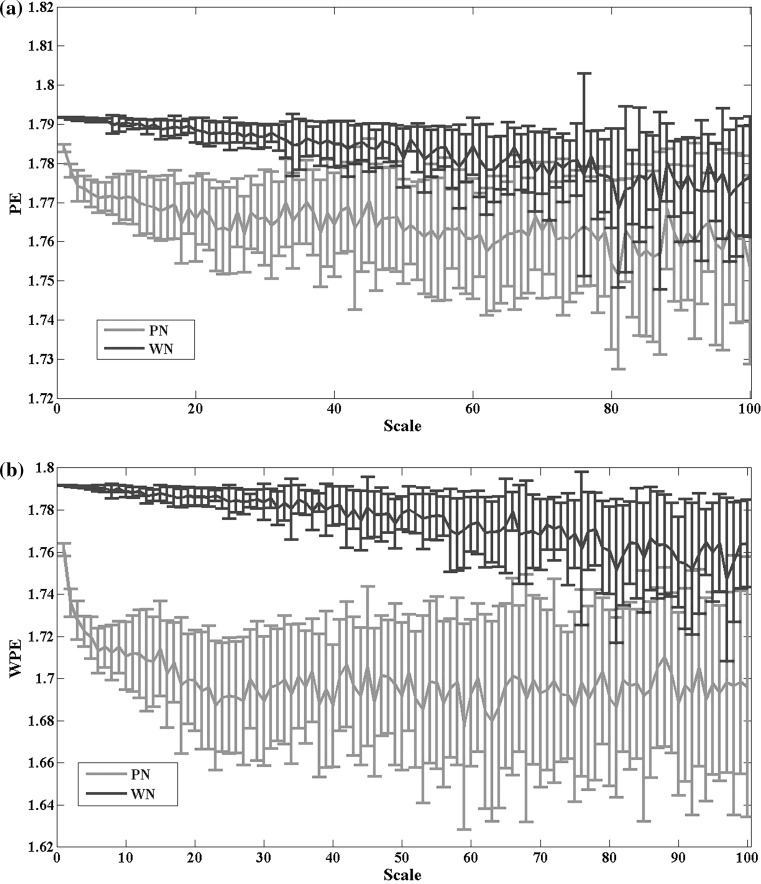

In order to test the behavior of the multi-scale WPE, 8 realizations of the white noise and 1/f noise are generated and each realization contains 10,000 data points. Then the signals were converted into successive coarse-grained versions under 1–100 time scales and the WPE and PE values of each time scale were computed. Figure 5 shows the multi-scale WPE and PE curves for the white noise and 1/f noise: notice that, as expected, the entropy value of the white noise decreases with the time scale gradually. However, the PE value of 1/f noise displays the similar trend to the time scale, which fails to distinguish the white noise and 1/f noise easily. In contrast, the weighted permutation entropy value of 1/f noise keeps relatively stable at larger time scales, which testifies that 1/f noise is more complex than the white noise in the deeper time scales on its own.

Fig. 5.

WPE and PE values of the white noise and 1/f noise with the time scale ranging from 1 to 100. PN represents 1/f noise, and WN represents the white Gaussian noise. Lines represent the mean value of entropies over 8 realizations for each time scale, and bars represent the SD

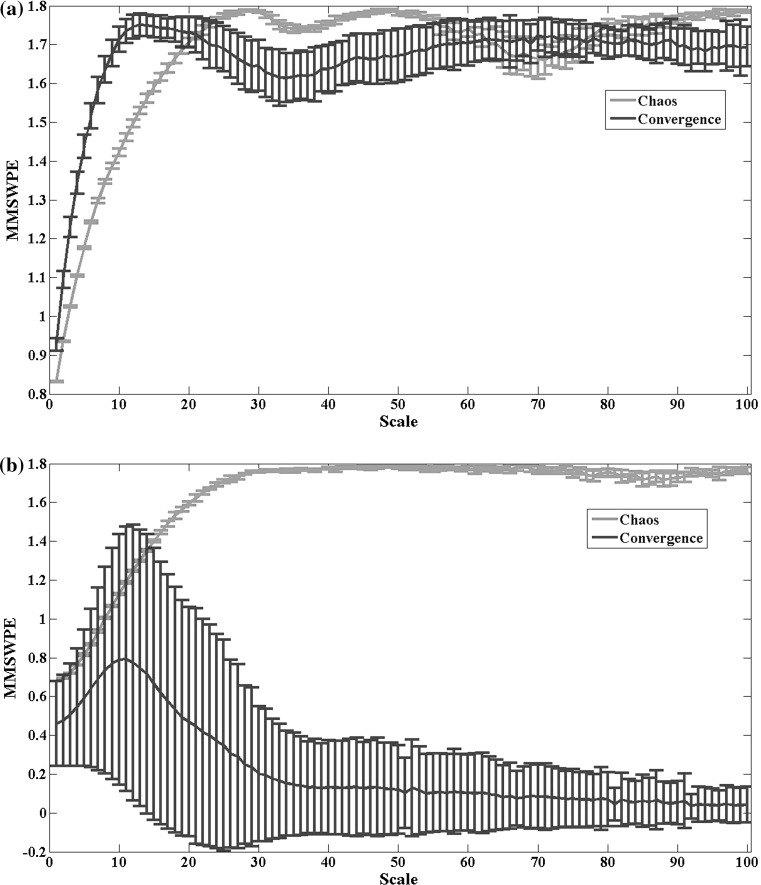

To understand the above behavior of the multivariate multi-scale weighted permutation entropy, two types of signals of 8 realizations, namely chaotic signals and convergent signals, were generated by altering the parameter ρ of the Lorentz system. And then the multivariate multi-scale entropy values were calculated for the trivariate Lorentz signals with a data length 10,000. As is shown in Fig. 6, MMSWPE can discriminate the chaotic signals from the convergent signals effectively compared with MMSPE method, manifested as little overlap between the two kinds of signals in most time scales.

Fig. 6.

MMSWPE and MMSPE values of the trivariate simulated signals generated by the Lorentz system with the time scale ranging from 1 to 100. The red line indicates the entropy values of the trivariate chaotic signals, and the blue line indicates the entropy values of the trivariate convergent signals. Lines represent the mean value of entropies over 8 realizations for each time scale, and bars represent the SD. (Color figure online)

Comparison between MMSWPE and MMSPE

To confirm the advantage of MMSWPE over MMSPE, the alpha rhythm, which is regarded as a sub-band with significant difference between AD and the control group (Cao et al. 2015), is selected for the comparison of the two methods in six different regions.

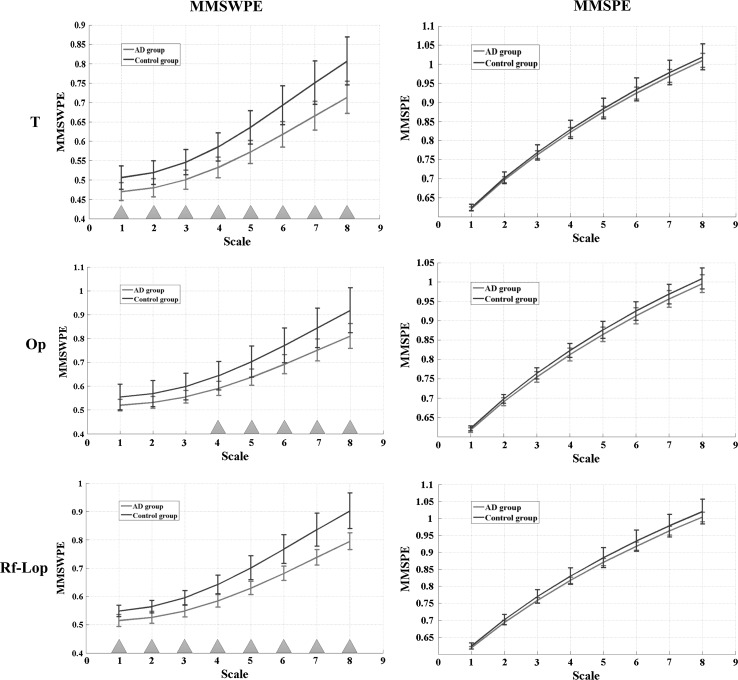

In order to achieve high confidence of the data, a sliding window of size 1 s (1024 data points) with an overlap of 0.75 s (768 data points) is used to the 16-channel recorded EEG data. And in the MMSWPE and MMSPE analysis, the embedding dimension was set to 5 and the time delay was set to 1. Besides, the data length was fixed and the time scale ranges from 1 to 8 (Bandt and Pompe 2002; Yi et al. 2014). The entropic estimates from individual sliding windows were averaged to obtain one entropic estimate per subject, and then the subject-level average estimates are used in the statistical analysis. One-way ANOVA test is applied to assess the differences of entropic values among the two groups at each time scale. In order to facilitate the comparison of the overall trend, the average slope values of the MMSWPE profiles are estimated by the least square method. To obtain the average slope value, the MMSWPE profile was divided into multiple parts and each of them was fitted with straight line, and then the slopes of them were averaged. The regions for which the average slope value of AD group is lower than that of the control group with the significant difference () were shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

The average MMSWPE and MMSPE values of the temporal (T), the occipitoparietal (Op) and the right frontal to the left occipitoparietal (Rf-Lop) regions in the alpha frequency band for different time scale (). Lines represent the mean value of entropies for each time scale, and bars represent the SD. The blue triangles below the graphs indicate that the difference between AD and the control group is significant (). (Color figure online)

It is found that the entropy value of AD group is decreased at each time scale in the temporal, the occipitoparietal, and the right frontal to the left occipitoparietal regions. Notably, the downward trend of MMSWPE is more obvious than that of MMSPE. Particularly, the significant difference between the two groups with the MMSWPE method appears at every time scale except scale 1–3 in the occipitoparietal region, while MMSPE reveals no significant difference.

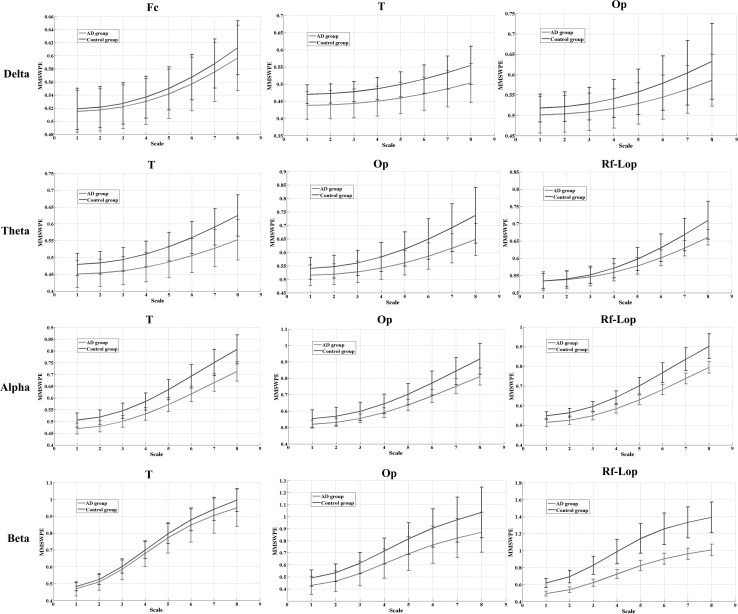

MMSWPE analysis of different regions in AD

To further investigate the complexity abnormity of AD group in different brain regions and time scales, the MMSWPE values of the six brain regions for the four sub-bands are calculated. It can be seen that the MMSWPE value shows an uptrend with the rising of time scale and the frequency. As is shown in Fig. 8, the decreased complexity of AD group compared with the control group is found in the temporal and occipitoparietal regions for all the rhythms and the time scales. In addition, it can also be observed in the right frontal to the left occipitoparietal regions for the theta, the alpha and the beta bands and in the frontal to central region for the delta band.

Fig. 8.

The MMSWPE values for AD and the control groups of which the decreased entropy value in AD is found at each time scale (). The red line represents AD group, and the blue line represents the control group. The bars represent the standard deviation. Fc frontal to central region, T temporal region, Op occipitoparietal region, and Rf-Lop right frontal to the left occipitoparietal region. (Color figure online)

Then the average slope values of the MMSWPE curves were computed for all the time scales and one-way ANOVA was applied to determine whether there are significant differences between both groups. To avoid spurious rejections, Bonferroni correction was applied and the significance level is set at for the comparison in four frequency bands. As is shown in Table 1, both the decreased complexity of AD group and the significant difference between the two groups are found in the temporal and occipitoparietal regions for the theta and the alpha bands. The difference can also be remarkably observed in the right frontal to the left occipitoparietal regions for all the frequency bands except for the delta band.

Table 1.

The statistical analysis for the average slope values of the MMSWPE profiles in the areas and sub bands with significant group difference (p < 0.0025)

| Area | AD patients (mean ± SD) | Control subjects (mean ± SD) | Statistical analysis p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Theta | |||

| T | 0.0147 ± 0.0034 | 0.0211 ± 0.0046 | 0.0002 |

| Op | 0.0191 ± 0.0037 | 0.0285 ± 0.0092 | 0.0009 |

| Rf-Lop | 0.0181 ± 0.0019 | 0.0254 ± 0.0051 | 1.93E−05 |

| (b) Alpha | |||

| T | 0.0361 ± 0.0033 | 0.0447 ± 0.0064 | 6.52E−05 |

| Op | 0.0427 ± 0.0052 | 0.0536 ± 0.0062 | 1.43E−05 |

| Rf-Lop | 0.0413 ± 0.0024 | 0.0525 ± 0.0079 | 1.47E−05 |

| (c) Beta | |||

| Rf-Lop | 0.0793 ± 0.0063 | 0.1197 ± 0.0202 | 4.74E−08 |

T temporal region, Op occipitoparietal region, and Rf-Lop right frontal to the left occipitoparietal region

Since it has been shown that the change of complexity is related to the slowing effect, we further investigated the correlation between the multiscale entropy and the power spectrum. One way ANOVA was applied for the relative power spectrum in different frequency bands and areas (see Table 2). It is demonstrated that significant group difference appears in the most areas for the theta band and Rf-Lop area for the beta band, while no significant difference is found in the alpha band. Moreover, we computed the Pearson Correlation Coefficients of theta power and MMSWPE as an example to illustrate the relation of two measures directly (see Table 3). Only the temporal and occipitoparietal region show weak correlation, indicating that MMSWPE is independent of the power in most brain regions and time scales.

Table 2.

The one-way ANOVA results (p values) of relative power in different bands and areas

| Band | Fp | Fc | T | Op | Rf-Lop | Lf-Lop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delta | 0.0298 | 0.4185 | 0.4273 | 0.4212 | 0.0412 | 0.6422 |

| Theta | 0.0234 | 6.52e−06 | 5.59e−06 | 2.55e−05 | 8.94e−06 | 5.11e−05 |

| Alpha | 0.0124 | 0.0271 | 0.0276 | 0.0075 | 0.0129 | 0.0030 |

| Beta | 0.0239 | 0.6585 | 0.1421 | 0.0540 | 0.0011 | 0.8931 |

The p values indicating significant group difference are marked with bold face

Table 3.

The Pearson Correlation Coefficients of theta power and MMSWPE for AD group in different scales and areas

| Scale | Fp | Fc | T | Op | Rf-Lop | Lf-Lop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0228 | 0.0439 | 0.4335 | 0.4406 | −0.0106 | 0.1230 |

| 2 | 0.0238 | 0.0371 | 0.4288 | 0.4343 | −0.0122 | 0.1213 |

| 3 | 0.0264 | 0.0230 | 0.4187 | 0.4220 | −0.0158 | 0.1197 |

| 4 | 0.0306 | 0.0045 | 0.4024 | 0.4046 | −0.0208 | 0.1167 |

| 5 | 0.0373 | −0.0166 | 0.3832 | 0.3848 | −0.0276 | 0.1163 |

| 6 | 0.0435 | −0.0343 | 0.3638 | 0.3632 | −0.0332 | 0.1125 |

| 7 | 0.0521 | −0.0482 | 0.3482 | 0.3466 | −0.0362 | 0.1109 |

| 8 | 0.0611 | −0.0540 | 0.3340 | 0.3321 | −0.0351 | 0.1087 |

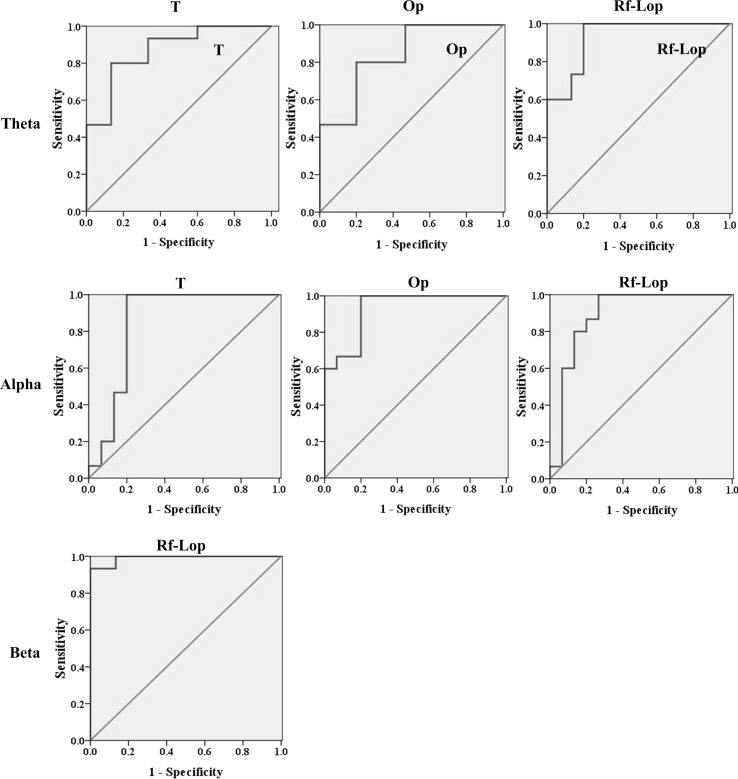

Finally, the ability of the MMSWPE measure to discriminate AD patients from the control subjects of the regions with significant differences was evaluated by means of the ROC plot function in SPSS 17.0 software. Before the ROC analysis, the binary logistic regression analysis is used to estimate the predictive probability which is generated by the binary logistic regression function of SPSS 17.0 automatically. Then the probability is applied to the ROC analysis. Figure 9 depicts the corresponding ROC curves and Table 4 shows the threshold, the sensitivity, specificity, the accuracy and the area under the ROC curve (AUC). According to the result, the highest specificity, accuracy and the AUC were reached in the right frontal to the left occipitoparietal region for the beta band.

Fig. 9.

The ROC curves which assesses the ability of the average slope values of the MMSWPE profiles to discriminate AD patients from the normal controls in the areas with significant group difference (p < 0.0025)

Table 4.

The ROC analysis results for the average slope of the MMSWPE profiles in the areas with significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.0025)

| Area | Threshold | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Theta | |||||

| T | 0.4796 | 80.0 | 86.7 | 83.4 | 0.87 |

| Op | 0.5083 | 80.0 | 80.0 | 80.0 | 0.84 |

| Rf-Lop | 0.2537 | 100.0 | 80.0 | 90.0 | 0.93 |

| (b) Alpha | |||||

| T | 0.4369 | 100.0 | 80.0 | 90.0 | 0.85 |

| Op | 0.2871 | 100.0 | 80.0 | 90.0 | 0.93 |

| Rf-Lop | 0.3223 | 100.0 | 73.4 | 86.7 | 0.89 |

| (c) Beta | |||||

| Rf-Lop | 0.6552 | 93.3 | 100.0 | 96.7 | 0.99 |

T temporal region, Op occipitoparietal region, and Rf-Lop right frontal to the left occipitoparietal region

Discussion

In this study, a modified method for the complexity analysis of AD is proposed which is proven to be more effective. Similarly, Labate et al. (2013) proposed MMSPE for assessing the complexity of AD and found that MMSPE had the possibility of AD detection. However, MMSPE does not take the importance of amplitude information into account, and its performance has not been verified by the model. Besides, the difference of the MMSPE values between AD and the control group at each time scale is very small without the statistical significant difference test. From the comparison between MMSWPE and MMSPE, it is worth noting that MMSWPE succeeds in distinguishing the complexity of chaos and convergence but MMSPE fails. Moreover, MMSWPE is able to discriminate AD patients from the control subjects with more distinct difference. The finding provides the evidence that MMSWPE is more suitable to character the complexity of multichannel noisy signals. This is attributed to the fact that MMSWPE retains the advantages of WPE and multivariate multi-scale method.

In the application of AD detection, the decreased complexity of AD compared with the control group is found in different regions and EEG sub-bands. Reportedly, the different frequency bands reflect separate brain dynamical systems (Jelles et al. 2008). It might be explained by the facts that higher frequency oscillations originate from a short-range neural connectivity, whereas lower-frequency oscillations encompass long-range neural connectivity (Hutcheon and Yarom 2000; Schnitzler and Gross 2005; Takahashi 2013; Von Stein and Sarnthein 2000). Hence, we infer that the complexity abnormality of different frequencies might be associated with the aberrant neural connectivity in AD. Moreover, Mattson (2004) convinced that the size of the temporal lobes correlated with learning and memory processes in AD patients is reduced because of degeneration of synapses. And Yang et al. (2013) found that MSE complexity in EEGs of the temporal and occipitoparietal electrodes correlated significantly with cognitive function. It is coincident that the significant decreased MMSWPE values of AD group are observed in the temporal and the occipitoparietal regions in the theta and the alpha sub-bands, which indicates that the decreased complexity reflects the degeneration of those regions in AD patients. In addition to the MMSPWE analysis, the correlation of the relative power with MMSWPE was also investigated. The results show that the MMSWPE could provide information beyond relative power.

Finally, a ROC curve was used to assess the effect of the average slope of MMSWPE curves in classifying AD and the normal controls. Our results suggest that the right frontal to the left occipitoparietal region is a typical area for differentiate functional decline with different frequencies associated with AD patients since its accuracy reaches 96.7 % for the beta bands. Similar to our findings, Escudero et al. (2006) used MSE to analyze the EEG background activity of AD patients. The average slope values of the MSE profiles for small time scales of the EEGs for AD is decreased at the electrode F7, Fp1, T3, T4 and C4, but no significant differences were found. Taking all discussed above into consideration, MMSWPE might be a potential method to distinguish AD patients from the normal controls.

Conclusion

In this paper, MMSWPE which combines WPE and the multivariate multi-scale method is proposed to quantify the complexity of EEG for AD detection. The detailed dynamic changes and improved quantification of the complexity in AD are observed. The effectiveness of MMSWPE is validated by both the simulated and the experimental signals. The simulation results demonstrate that MMSWPE retains the advantages of WPE and multivariate multi-scale method and is capable of distinguishing the system with different complexity, but MMSPE performs unsatisfactorily. Besides, the superiority of MMSWPE compared with MMSPE is also been verified by the analysis of the alpha rhythm for AD. In the application to the EEG recordings of AD, the MMSWPE values of the canonical frequency bands for six different brain regions over eight time scales are calculated. And we found that the complexity is decreased differently in AD patients for different frequency bands and brain regions. The decreased complexity and significant difference are found in the temporal and occipitoparietal regions for the theta and the alpha bands, which are also distributed in the right frontal to the left occipitoparietal region for the theta, the alpha and the beta bands at each time scale. The abnormalities in the dynamics in AD patients caused by cortical changes can be revealed by MMSWPE effectively. Our findings seem to highlight the potential utility of MMSWPE as a modified method for the assessment of AD and suggests that MMSWPE could be a useful tool to investigate the EEG background activity characteristics.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Tianjin Municipal Natural Science Foundation under Grants 13JCZDJC27900, Tangshan Science and Technology Support Project under Grants 14130223B and Jilin Provincial Natural Science Foundation under Grants 20130101170JC.

References

- Abásolo D, Hornero R, Espino P, Poza J, Sánchez CI, de la Rosa R. Analysis of regularity in the EEG background activity of Alzheimer’s disease patients with approximate entropy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116:1826–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abásolo D, Hornero R, Espino P, Alvarez D, Poza J. Entropy analysis of the EEG background activity in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Physiol Meas. 2006;27:241–253. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/27/3/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abásolo D, Escudero J, Hornero R, Gómez C, Espino P. Approximate entropy and auto mutual information analysis of the electroencephalogram in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2008;46:1019–1028. doi: 10.1007/s11517-008-0392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed MU, Mandic DP. Multivariate multiscale entropy analysis. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2012;19:91–94. doi: 10.1109/LSP.2011.2180713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M, Akrofi K, Schiffer R, O’Boyle MW. EEG Patterns in Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients. Open Neuroimag J. 2008;2:52–55. doi: 10.2174/1874440000802010052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandt C, Pompe B. Permutation entropy: a natural complexity measure for time series. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;88:174102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.174102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Başar E, Güntekin B, Atagün I, Gölbaşı BT, Tülay E, Özerdem A. Brain’s alpha activity is highly reduced in euthymic bipolar disorder patients. Cogn Neurodyn. 2012;6:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s11571-011-9172-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørk MH, Stovner LJ, Engstrøm M, Stjern M, Hagen K, Sand T. Interictal quantitative EEG in migraine: a blinded controlled study. J Headache Pain. 2009;10:331–339. doi: 10.1007/s10194-009-0140-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzo AA, Gesierich B, Santi M, Tassinari C, Birbaumer N, Rubboli G. Permutation entropy to detect vigilance changes and preictal states from scalp EEG in epileptic patients: a preliminary study. Neurol Sci. 2008;29:3–9. doi: 10.1007/s10072-008-0851-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Tung W, Gao JB, Protopopescu VA, Hively LM. Detecting dynamical changes in time series using the permutation entropy. Phys Rev E. 2004;70:046217. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.046217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao YZ, Cai LH, Wang J, Wang RF, Yu HT, Cao YB, Liu J. Characterization of complexity in the electroencephalograph activity of Alzheimer’s disease based on fuzzy entropy. Chaos. 2015;25:083116. doi: 10.1063/1.4929148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M, Goldberger AL, Peng CK. Multiscale entropy analysis of complex physiologic time series. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;89:068102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.068102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czigler B, Csikós D, Hidasi Z, Anna Gaál Z, Csibri E, Kiss E, Salacz P, Molnár M. Quantitative EEG in early Alzheimer’s disease patients—power spectrum and complexity features. Int J Psychophysiol. 2008;68:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauwels J, Vialatte F, Cichocki A. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease from EEG Signals: where are we standing? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:487–505. doi: 10.2174/156720510792231720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauwels J, Vialatte F, Musha T, Cichocki A. A comparative study of synchrony measures for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease based on EEG. Neuroimage. 2010;49:668–693. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauwels J, Srinivasan K, Ramasubba Reddy M, Musha T, Vialatte FB, Latchoumane C, Jeong J, Cichocki A. Slowing and loss of complexity in Alzheimer’s EEG: Two sides of the same coin? Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;2011:53962. doi: 10.4061/2011/539621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng B, Liang L, Li SN, Wang RF, Yu HT, Wang J, Wei XL. Complexity extraction of electroencephalograms in Alzheimer’s disease with weighted-permutation entropy. Chaos. 2015;25:043105. doi: 10.1063/1.4917013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudero J, Abásolo D, Hornero R, Espino P, López M. Analysis of electroencephalograms in Alzheimer’s disease patients with multiscale entropy. Physiol Meas. 2006;27:1091–1106. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/27/11/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadlallah B, Chen B, Keil A, Príncipe J. Weighted-permutation entropy: a complexity measure for time series incorporating amplitude information. Phys Rev E. 2013;87:022911. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.87.022911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati S, Ahmadlou M, Gharib M, Vameghi R, Sajedi F. Down syndrome’s brain dynamics: analysis of fractality in resting state. Cogn Neurodyn. 2013;7:333–340. doi: 10.1007/s11571-013-9248-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheon B, Yarom Y. Resonance, oscillation and the intrinsic frequency preferences of neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:216–222. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01547-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelles B, Scheltens P, van der Flier WM, Jonkman EJ, da Silva FH, Stam CJ. Global dynamical analysis of the EEG in Alzheimer’s disease: frequency-specific changes of functional interactions. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119:837–841. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller K, Wittfeld K. Distances of time series components by means of symbolic dynamics. Int J Bifurcat Chaos. 2004;14:693–703. doi: 10.1142/S0218127404009387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labate D, La Foresta F, Morabito G, Palamara I, Morabito FC. Entropic measures of EEG complexity in Alzheimer’s disease through a multivariate multiscale approach. IEEE Sens J. 2013;13:3284–3292. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2013.2271735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laske C, Sohrabi HR, Frost SM, et al. Innovative diagnostic tools for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:561–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Ouyang G, Richards DA. Predictability analysis of absence seizures with permutation entropy. Epilepsy Res. 2007;77:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Cui S, Voss LJ. Using permutation entropy to measure the electroencephalographic effect of sevoflurane. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:448–456. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318182a91b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, et al. Multiple characteristics analysis of Alzheimer’s electroencephalogram by power spectral density and Lempel–Ziv complexity. Cogn Neurodyn. 2016;10:121–133. doi: 10.1007/s11571-015-9367-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz EN. Deterministic nonperiodic flow. J Atmos Sci. 1963;20:130–141. doi: 10.1175/1520-0469(1963)020<0130:DNF>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2004;430:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabito FC, Labate D, La Foresta F, Bramanti A, Morabito G, Palamara I. Multivariate multi-scale permutation entropy for complexity analysis of Alzheimer’s disease EEG. Entropy. 2012;14:1186–1202. doi: 10.3390/e14071186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti DV, Fracassi C, Pievani M, Geroldi C, Binetti G, Zanetti O, Sosta K, Rossini PM, Frisoni GB. Increase of theta/gamma ratio is associated with memory impairment. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsen E, Sleigh JW, Dahan A. Permutation entropy of the electroencephalogram: a measure of an aesthetic drug effect. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:810–821. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang GX, Li XL, Dang CY, Richards DA. Deterministic dynamics of neural activity during absence seizures in rats. Phys Rev E. 2009;79:041146. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.79.041146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang GX, Dang CY, Richards DA, Li XL. Ordinal pattern based similarity analysis for EEG recordings. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;121:694–703. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Kim S, Kim CH, Cichocki A, Kim K. Multiscale entropy analysis of EEG from patients under different pathological conditions. Fractals. 2007;15:399–404. doi: 10.1142/S0218348X07003691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schinkel S, Marwan N, Kurths J. Order patterns recurrence plots in the analysis of ERP data. Cogn Neurodyn. 2007;1:317–325. doi: 10.1007/s11571-007-9023-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinkel S, Marwan N, Kurths J. Brain signal analysis based on recurrences. J Physiol Paris. 2009;103:315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler A, Gross J. Normal and pathological oscillatory communication in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:285–296. doi: 10.1038/nrn1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T. Complexity of spontaneous brain activity in mental disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talebi N, Nasrabadi AM, Curran T. Investigation of changes in EEG complexity during memory retrieval: the effect of midazolam. Cogn Neurodyn. 2012;6:537–546. doi: 10.1007/s11571-012-9214-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timothy LT, Krishna BM, Menon MK, Nair U. Permutation entropy analysis of EEG of mild cognitive impairment patients during memory activation task. Fractals, wavelets, and their applications. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 395–406. [Google Scholar]

- van der Hiele K, Vein AA, Reijntjes RH, Westendorp RG, Bollen EL, van Buchem MA, van Dijk JG, Middelkoop HA. EEG correlates in the spectrum of cognitive decline. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:1931–1939. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Stein A, Sarnthein J. Different frequencies for different scales of cortical integration: from local gamma to long range alpha/theta synchronization. Int J Psychophysiol. 2000;38:301–313. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8760(00)00172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RF, Wang J, Yu HT, Wei XL, Yang C, Deng B. Power spectral density and coherence analysis of Alzheimer’s EEG. Cogn Neurodyn. 2015;9:291–304. doi: 10.1007/s11571-014-9325-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woon WL, Cichocki A, Vialatte F, Musha T. Techniques for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease using spontaneous EEG recordings. Physiol Meas. 2007;28:335–347. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/28/4/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang AC, et al. Cognitive and neuropsychiatric correlates of EEG dynamic complexity in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;47:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi GS, et al. Ordinal pattern based complexity analysis for EEG activity evoked by manual acupuncture in healthy subjects. Int J Bifurcat Chaos. 2014;24:1450018. doi: 10.1142/S0218127414500187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]