Abstract

We have discovered a novel series of tetrahydrobenzimidazoles 3 as TGR5 agonists. Initial structure–activity relationship studies with an assay that measured cAMP levels in murine enteroendocrine cells (STC-1 cells) led to the discovery of potent agonists with submicromolar EC50 values for mTGR5. Subsequent optimization through methylation of the 7-position of the core tetrahydrobenzimidazole ring resulted in the identification of potent agonists for both mTGR5 and hTGR5 (human enteroendocrine NCI-H716 cells). While the lead compounds displayed low to moderate exposure after oral dosing, they significantly reduced blood glucose levels in C57 BL/6 mice at 30 mg/kg and induced a 13–22% reduction in the area under the blood glucose curve (AUC)0–120 min in oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT).

Keywords: TGR5, tetrahydrobenzimidazoles, OGTT, type 2 diabetes

TGR5 (also known as GPBAR1, M-BAR, or GPCR19) is a G-protein coupled receptor for bile acids (BAs).1 It is broadly expressed in human tissues, such as the GI tract, gall bladder, spleen, lung, brown adipose tissue, and placenta.2−4 Activation of TGR5 by BAs transduces signal through Gs protein-mediated cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) accumulation and downstream mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. It has been demonstrated that TGR5 activation could regulate a variety of metabolic processes, including hormonal control of energy expenditure.5−8 For example, mice fed a high fat diet containing 0.5% cholic acid gained less weight than the controls on a high fat diet alone. Moreover, significant fat accumulation and weight gain were observed in TGR5 knockout mice on a high fat diet.9,10 It has also been reported that stimulation of STC-1 cells with BAs elevated glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1) secretion, which could improve glucose homeostasis via various mechanisms including stimulation of pancreatic insulin secretion and inhibition of glucagon secretion.11 While application of this mechanism toward a clinically relevant therapy is still at an early stage, TGR5 has emerged as a promising metabolic disease target. In particular, a potent and selective TGR5 agonist may be beneficial for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity.

Design and evaluation of analogues of natural BAs afforded a potent and selective steroidal TGR5 agonist INT-777, which was poised to enter Phase I trials.12 Investigation of nonsteroidal chemical templates may lead to compounds that exhibit better selectivity for TGR5 over related receptors (i.e., farnesoid X receptor). There have been several reports in the literature of synthetic, nonsteroidal TGR5 agonists.13−22 Several series exhibited potent TGR5 agonist activity in cell-based functional assays and were orally efficacious in lowering glucose levels in rodents. Herein, we report our effort to develop novel and selective TGR5 agonists for a treatment of metabolic disease. The goal of the program was to identify orally efficacious TGR5 agonists with dual activities on the human and mouse receptors to enable evaluation in disease-relevant preclinical models.

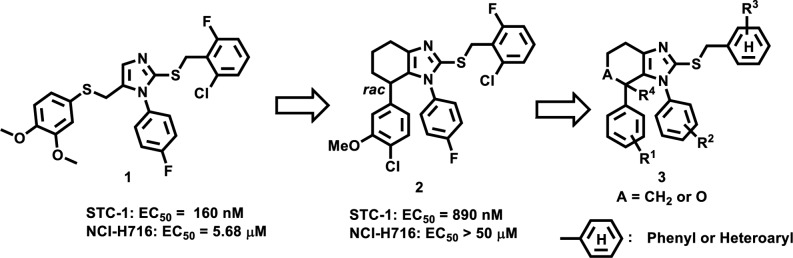

We have recently described a series of 2-thio-5-thiomethyl substituted imidazole scaffold as potent TGR5 agonists (Figure 1).23 Compound 1 displayed an EC50 value of 160 nM against mouse TGR5 (mTGR5) expressed STC-1 cell line, 5.68 μM in human TGR5 (hTGR5) expressed NCI-H716 cell line, and possessed a trend of lowering glucose level in OGTT (Supporting Information, SI). Encouraged by this finding, we investigated ring restriction strategy on two S-containing side chains of the core imidazole ring to develop a novel series of TGR5 agonists. This prompted us to synthesize a few small chemical libraries based on template 1 for preliminary screening. A tetrahydrobenzimidazole 2 was identified as an interesting hit given its moderate potency in STC-1 cells. Compound 2 displayed an EC50 of 890 nM against mTGR5 but was inactive against hTGR5, perhaps as a consequence of the relatively low amino acid sequence identity (83%) between the two receptors.3 The first goal of our medicinal chemistry effort was to maximize mTGR5 potency to assess pharmacology of TGR5 agonists in mouse models. Subsequently, the focus would shift toward improvement of the hTGR5 activity to identify a potent and orally bioavailable lead for clinical development. Beginning with hit compound 2, a novel series of tetrahydrobenzimidazoles (3) were elaborated during the lead optimization process. We mainly focused on structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies of R1–R3 on the pendant aromatic rings as well as R4 and A on the core heterocyclic ring.

Figure 1.

Tetrahydrobenzimidazoles via ring restriction.

The general synthetic routes to all compounds in Table 1 and 2 are shown in Schemes 1 and 2 in SI. We began our SAR studies by investigating the substituents at the R1, R2, and R3 positions as well as the core tetrahydrobenzimidazole ring (Table 1). Replacement of the 4-Cl group of R1 (2, EC50 890 nM) with a 4-F slightly increased mTGR5 potency (20, EC50 550 nM), whereas replacement with a methoxy group (21, EC50 125 nM) yielded a ∼7-fold improvement in mTGR5 potency. 3,4-Dimethoxy-substituted analogue 21 had detectable activity in the hTGR5 assay with an EC50 value of 12.5 μM. A clear preference for the S*-enantiomer (21a, mTGR5 EC50 73 nM) over the R*-enantiomer (21b, mTGR5 EC50 9.39 μM) was demonstrated. Quite strikingly, further modifications of the R1 substituents were generally not associated with improvements in mTGR5 potency. In particular, a more than 20-fold loss of mTGR5 potency was evident by converting the 3,4-di-MeO group into the 3,4-ethylenedioxy group (22, mTGR5 EC50 2.93 μM). Compound 23, a very close analogue of compound 21 bearing the 3,4-methylenedioxy group, had poor potency in the mTGR5 assay (EC50 ∼26 μM). Likewise, replacement of the 3-MeO group of 21 with a 3-Cl group resulted in a significant loss of the mTGR5 activity (24, mTGR5 EC50 1.51 μM) and abolished hTGR5 activity. Finally, removal of the 4-MeO group at the R1 position of 21 led to a greater than 20-fold loss of the mTGR5 potency (25, mTGR5 EC50 2.78 μM).

Table 1. SAR of R1, R2, R3, and A Groups on Imidazoles 3.

| ID | R1 | R2 | R3 | A | STC-1 (mouse)a EC50 (nM) | NCI-H716 (human)b EC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 890 | >50000 |

| 20 | 3-OMe-4-F | 4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 550 | >50000 |

| 21 | 3,4-di-OMe | 4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 125 | 12500 |

| 21a(S*)c | 3,4-di-OMe | 4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 73 | 3400 |

| 21b(R*)d | 3,4-di-OMe | 4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 9390 | >50000 |

| 22 | 3,4-ethylenedioxy | 4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 2930 | >50000 |

| 23 | 3,4-methylenedioxy | 4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 25980 | >50000 |

| 24 | 3-Cl-4-OMe | 4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 1505 | >50000 |

| 25 | 3-OMe | 4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 2776 | >50000 |

| 26 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 4-OMe | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 38160 | >50000 |

| 27 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 4-Cl | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 18550 | >50000 |

| 28 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 3,4-di-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 509 | >50000 |

| 29 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 3-OMe-4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 313 | 30500 |

| 30 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 3-Me-4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 490 | >50000 |

| 31 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 3-Cl-4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 812 | >50000 |

| 32 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 3-CF3-4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 13400 | >50000 |

| 33 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 2,4-di-F | 2-F-6-Cl | CH2 | 1340 | 35180 |

| 34 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 4-F | 2,6-di-F | CH2 | 690 | >50000 |

| 35 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 4-F | 2-F-6-NO2 | CH2 | 397 | >50000 |

| 36 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 4-F | 2-F-6-Br | CH2 | 621 | >50000 |

| 37 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 4-F | 2-F-6-OMe | CH2 | 4812 | >50000 |

| 38 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 4-F | 2,5-di-F | CH2 | 7415 | >50000 |

| 39 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 4-F | 2,4-di-F | CH2 | 26440 | >50000 |

| 40 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 4-F | 3-F-5-Cl | CH2 | >50000 | >50000 |

| 41 | 3,4-di-OMe | 4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | O | 330 | 20500 |

| 42 | 3-OMe-4-Cl | 4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | O | 778 | >50000 |

| 43 | 3-OMe-4-F | 4-F | 2-F-6-Cl | O | 214 | >50000 |

TGR5 activation in the stimulation of cAMP level in STC-1 cells; for EC50 > 10000 nM (n = 1) and for EC50 < 10000 nM (n > 2, average values, SEM < ±25%);.

TGR5 activation in the stimulation of cAMP level in NCI-H716 cells; for EC50 > 10000 nM (n = 1) and for EC50 < 10000 nM (n > 2, average values, SEM< ± 25%).

Arbitrarily assigned as “S”.

Arbitrarily assigned as “R”(see SI).

Table 2. SAR of R1, R3, and R4 Groups on Tetrahydrobenzimidazoles 3.

TGR5 activation in the stimulation of cAMP level in STC-1 cells; for EC50 > 10000 nM (n = 1) and for EC50 < 10000 nM (n > 2, average values, SEM< ± 25%).

TGR5 activation in the stimulation of cAMP level in NCI-H716 cells; for EC50 > 10000 nM (n = 1) and for EC50 < 10000 nM (n > 2, average values, SEM ± 25%).

Kinetic solubility (see SI).

Two enantiomers were resolved (see SI).

We then turned our attention toward surveying the R2 position. Replacing the 4-F group of compound 2 with the more polar 4-OMe group (26) significantly reduced mTGR5 activity. Moreover, analogue 27 bearing the 4-Cl substituent at the R2 position resulted in a 20-fold loss of mTGR5 potency (EC50 18.55 μM), suggesting there may be a very tight pocket for ligand–receptor binding in this area. Compared with the 4-postion of the R2 phenyl ring, the 3-position provided some flexibility for substitution. Addition of a F, Cl, Me, or MeO group ortho to the 4-F group on the phenyl ring resulted in a slight improvement in mTGR5 potency as shown by 28 (EC50 509 nM), 29 (EC50 313 nM), 30 (EC50 490 nM), and 31 (EC50 812 nM). In contrast, addition of a 3-CF3 substituent significantly attenuated activity (32, mTGR5 EC50 of 13.4 μM).The 2-position of the phenyl ring appeared somewhat less tolerant, as incorporation of a F substituent led to a 2-fold loss of mTGR5 potency (33 EC50 1.34 μM).

We next sought to improve TGR5 potency by alteration of the R3 phenyl ring. A 2,6-substition pattern with halogens or with one halogen and one electron withdrawing group such as nitro were essential for optimal mTGR5 potency, as shown by the 2-F-6-Cl (2), 2,6-di-F (34), 2-F-6-NO2 (35), and 2-F-6-Br (36) substituted analogues. Replacement of one halogen with an electron donating methoxy group reduced the mTGR5 potency significantly (37, EC50 4.81 μM). A 2,4-, 2,5-, or 3,5-substitution pattern dramatically attenuated the mTGR5 potency as indicated by compounds 38–40 with EC50 values in the high micromolar range.

The core tetrahydrobenzimidazole ring was also examined for effects on potency and to adjust pharmaceutical properties of this novel series of TGR5 agonists. Replacement of the core tetrahydrobenzimidazole ring with the more polar oxygen-containing tetrahydropyranoimidazole ring was well tolerated (compounds 41–43). Compounds 41 (EC50 330 nM), 42 (EC50 778 nM), and 43 (EC50 214 nM) all displayed comparable mTGR5 potencies to the corresponding tetrahydrobenzimidazole containing analogues (2, 20, and 21).

Having established the SAR for mTGR5 agonist potency, we then focused on boosting the hTGR5 activity. As illustrated in Table 1, some compounds displayed satisfactory potency on the mouse receptor but were significantly less potent on the human receptor. Low amino acid sequential identity between the human and mouse TGR5 receptors could be a critical issue in the identification of dual agonists.3 However, expression level of TGR5 in different cell lines would also play a critical role on the potency evaluation. It is possible that rather lower expression of human TGR5 attributed to the lower human TGR5 potency observed in NCI-716 cells. To improve the hTGR5 activity, we decided to further examine the tetrahydrobenzimidazole core by a variety of modifications such as varying the ring size, adding substitution on the ring, aromatization of the core, etc. (data not shown). To our satisfaction, the potency of the 7-methyl tetrahydrobenzimidazole analogue with a 3,4-di-MeO substitution at the R1 position (45) was significantly improved compared to the unsubstituted analogue, with EC50 values of 10 and 440 nM against mTGR5 and hTGR5, respectively (Table 2). In contrast, the potency of the 3-OMe-4-Cl (44) and 3-OMe-4-F (46) substituted analogues was comparable to the nonmethylated analogues in Table 1, although compound 46 had a measurable EC50 value against hTGR5. Given that addition of a methyl group at the 7-position tended to boost hTGR5 potency, other small alkyl substituents were incorporated into the 7-position of the core ring. Surprisingly, introduction of slightly larger or more polar substituents such as 7-Et (47), 7-hydroxymethyl (48), or 7-fluoromethyl (49) abolished hTGR5 activity and significantly reduced mTGR5 potency, suggesting a region of low steric bulk tolerance. Hence, the 7-methyl group was retained in subsequent SAR studies. Compounds with dual activity against mTGR5 and hTGR5 were screened in an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in C57 BL/6 mice (see Table 5 in SI). Surprisingly, those compounds possessed less optimal glucose lowering activity in vivo, probably due to their low aqueous solubility at the physiological condition. For example, kinetic solubility of 45 measured in PBS (pH = 7.4) was only 5.83 μM, which might lead to less in vivo efficacy due to inadequate intestinal exposure. To improve aqueous solubility, we then focused on modifying the pendant phenyl ring at the 4-position. Interestingly, substitution at the 4-position of the phenyl ring was tolerated as long as the 2,6-di-F substitution pattern was maintained. It was therefore possible to install a polar functional group at the 4-position to improve aqueous solubility and to target higher intestinal exposure for in vivo studies. A polar group such as a carboxylic acid (51), a terminal alcohol (52), a PEG chain (53), or a terminal amine (54–57) at the 4-position of the pendant phenyl group was tolerated and yielded compounds with favorable aqueous solubility. Compound 54 displayed EC50 of 120 nM against mTGR5 and 390 nM against hTGR5 as well as superior aqueous solubility in PBS (53.6 μM). Replacement of one methoxy group with a halogen at the R1 position adversely affected hTGR5 activity, as shown by compounds 55–57 with EC50 values in the single to double digit micromolar range, although the effect on mTGR5 activity was more subtle. Replacement of the R3-substituted pendant phenyl ring with an electron deficient heteroaryl ring such as 2,6-di-F-4-pyridine (59) or 2,6-pyrimidine (59–61) provided compounds with moderate potency against both mouse and human TGR5 receptors while improving aqueous solubility in PBS.

Selected compounds were evaluated in a 24 h mouse pharmacokinetic study at an oral dose of 20 mg/kg and an iv dose of 5 mg/kg in 20% HPBCD vehicle (Table 3). Compounds 54, 55, and 56 bearing an amine side chain at the 4-position of the pendant phenyl ring demonstrated moderate oral exposure in plasma (AUClast = 9347, 2543, and 7156 ng·h/mL). They had moderate clearance (9.68, 18.1, and 10.2 mL/min kg) and a low volume of distribution at steady state (Vss = 0.947, 1.63, and 0.818 L/kg), which were suitable for further investigation in preclinical animal studies for an antidiabetic effect. Compounds 60 and 61 with a pyrimidine ring in place of the R3 phenyl ring possessed a different PK profile. Both compounds displayed poor exposure, high clearance, and low oral bioavailability. High clearance combined with moderate solubility are likely responsible for the observed low exposure. Nevertheless, we postulated that the intestinal exposure of both compounds after oral dosing may be sufficient to activate TGR5 in the GI tract and thus increase GLP-1 secretion and lower blood glucose. Furthermore, compounds possessing poor systemic exposure such as 60 and 61 could act as GI restricted ligands to bind directly to the TGR5 receptor in the GI tract via local administration (vide infra). Hence, compounds in Table 3 with different PK profiles were chosen to advance to in vivo screening.

Table 3. In Vivo Mouse DMPK Profiles of Selected Compoundsa.

| ID | POb (mpk) | t1/2 (h) | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUClast (h·ng/mL) | IVc (mpk) | Vss (L/kg) | CL (mL/min/kg) | F (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54 | 20 | 2.10 | 2893 | 9347 | 5 | 0.947 | 9.68 | 27.5 |

| 55 | 20 | 1.33 | 918 | 2543 | 5 | 1.63 | 18.1 | 13.9 |

| 56 | 20 | 2.00 | 2410 | 7156 | 5 | 0.818 | 10.2 | 22.1 |

| 60 | 20 | NDd | 507 | 527 | 5 | 1.43 | 58.4 | 9.44 |

| 61 | 20 | NDd | 913 | 785 | 5 | 0.856 | 45.3 | 10.8 |

C57 BL/6 mice (average value, n = 3).

PO (20 mg/kg) in 20% HPBCD.

IV (5 mg/kg) in 20% HPBCD.

ND = not determined.

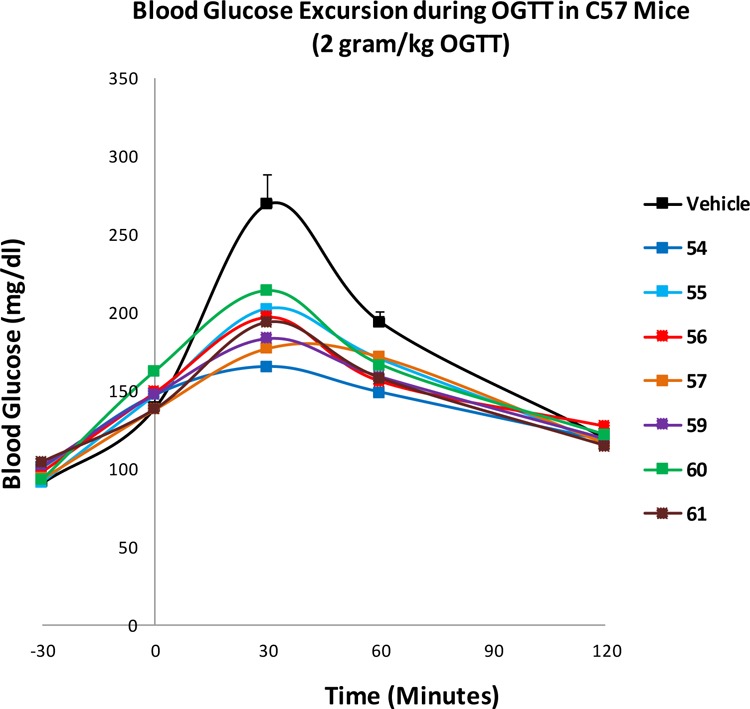

Compounds 51 and 54–61 were evaluated for in vivo glucose lowering activity in an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in C57 BL/6 mice. As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the areas under the curve (AUC)0–120 min for blood glucose levels versus time were calculated after a single oral administration of test compounds at 30 mg/kg in two separate studies. All compounds caused a statistically significant 13–22% of reduction in blood glucose AUC0–120 min compared with the vehicle control group with the exception of compound 60, which showed an 11% reduction with no statistical significance (Figures 2 and 3 and Table 4). Compound exposure levels at 2 h were measured to assess the PK/PD relationship as illustrated in Table 4. Compounds 51 and 53 to 57 with solubilizing side chains such as a carboxylic acid, a terminal amine, or a short chain PEG group displayed robust glucose-lowering activity in the OGTT. Plasma exposures at 2 h for compounds 54–57 were moderate and ranged from 1- to 18-fold the mTGR5 EC50 values. Compound 54 was most efficacious in the OGTT, causing a 22% absolute AUC0–120 min decrease relative to vehicle. Interestingly, less soluble and poorly absorbed compounds exhibited a comparable glucose-lowering effect as the more soluble TGR5 agonists. For example, following oral administration of 59 or 61 at 30 mg/kg, absolute AUC0–120 min decreased by 17.9% compared to the control group despite 2 h plasma levels of only 0.1 and 0.28 μM, respectively. These results may suggest that systemic exposure is not required for acute oral efficacy. The good efficacy observed may be due to a local intracolonic mechanism for TGR5 stimulating GLP-1 release.17,18 There have been increasing efforts to develop gut-restricted TGR5 agonists specifically targeting the GI tract.21 While orally bioavailable TGR5 agonists may be expected to stimulate the release of GLP-1 from the gut, increase insulin sensitivity, and improve glucose tolerance, recent studies have suggested that systemic exposure could simultaneously trigger filling of the gallbladder leading to a dramatic increase in gallbladder volume. GI restricted TGR5 agonists are a potential strategy to target the intestine locally to minimize this unwanted side effect. Hence, compounds with low systemic exposure such as 59 or 61 could also potentially serve as tool compounds to further investigate chronic in vivo pharmacology with minimal effects on gallbladder function.

Figure 2.

Study 1: OGTT studies of 54–57 and 59–61 in C57/BL6 mice. Compound (30 mg/kg in 20% HPBCD) or 20% HPBCD (vehicle control) was orally administered at −30 min of OGTT followed by oral glucose challenge at 2.0 g/kg at 0 min. Blood glucose was measured at −30, 0, 30, 60, and 120 min after administration (n = 8 animals/group).

Figure 3.

Study 2: OGTT studies of 51, 53 and 58 in C57 BL/6 mice. Compound (30 mg/kg in 20% HPBCD) or 20% HPBCD (vehicle control) was orally administered at −30 min of OGTT followed by oral glucose challenge at 2.0 g/kg at 0 min. Blood glucose was measured at −30, 0, 30, 60, and 120 min after administration (n = 8 animals/group).

Table 4. Efficacy and Plasma Concentrations of Compounds in Murine OGTT.

| ID | study | absolute AUC 0–120 min Decrease (%)a | ANOVA analysis | plasma conc @ 2 h (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54 | 1 | 22.6 | P < 0.0001 | 2.21 |

| 55 | 1 | 13.7 | P < 0.001 | 1.61 |

| 56 | 1 | 15.5 | P < 0.001 | 2.11 |

| 57 | 1 | 17.4 | P < 0.0001 | 0.76 |

| 59 | 1 | 17.9 | P < 0.0001 | 0.10 |

| 60 | 1 | 11.1 | nsb | 0.20 |

| 61 | 1 | 17.9 | P < 0.0001 | 0.28 |

| 51 | 2 | 17.8 | P < 0.001 | ndc |

| 53 | 2 | 17.5 | P < 0.001 | nd |

| 58 | 2 | 19.1 | P < 0.001 | nd |

Absolute AUC0–120 min decrease reflects changes in blood glucose levels from time 0 to 120 min compared with the vehicle.

No significance.

Not determined.

In summary, optimization of a series of tetrahydrobenzimidazoles and tetrahydropyranoimidazoles guided by in vitro cAMP assays produced several lead compounds with TGR5 activity in murine (STC-1) and human (NCI-H716) enteroendocrine cells. Furthermore, compounds with moderate or low oral exposure both significantly reduced blood glucose excursion during an OGTT study in C57 BL/6 mice. These compounds therefore deserve to be further tested in chronic models to investigate the therapeutic potential as novel TGR5 agonists for metabolic disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the ADME/PK, Analytical Research, and Lead Generation Biology teams at Janssen Research and Development for support. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Mark Macielag for scientific discussion and revising the manuscript.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00116.

Experimental procedures for the synthesis of 2 and 41 and characterization data for 2, 20–61 as well as in vitro and in vivo biological protocols (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Tiwari A.; Maiti P. TGR5: an emerging bile acid G-protein-coupled receptor target for the potential treatment of metabolic disorders. Drug Discovery Today 2009, 14, 523–530. 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T.; Miyamoto Y.; Nakamura T.; Tamai Y.; Okada H.; Sugiyama E.; Nakamura T.; Itadani H.; Tanaka K. Identification of membrane-type receptor for bile acids (M-BAR). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 298, 714–719. 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02550-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata Y.; Fujii R.; Hosoya M.; Harada M.; Yoshida H.; Miwa M.; Fukusumi S.; Habata Y.; Itoh T.; Shintani Y.; Hinuma S.; Fujisawa Y.; Fujino M. A. G protein-coupled receptor responsive to bile acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 9435–9440. 10.1074/jbc.M209706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C.; Pellicciari R.; Pruzanski M.; Auwerx J.; Schoonjans K. Targeting bile-acid signalling for metabolic diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 678–693. 10.1038/nrd2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M.; Houten S. M.; Mataki C.; Christoffolete M. A.; Kim B. W.; Sato H.; Messaddeq N.; Harney J. W.; Ezaki O.; Kodama T.; Schoonjans K.; Bianco A. C.; Auwerx J. Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature 2006, 439, 484–489. 10.1038/nature04330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prawitt J.; Caron S.; Staels B. Bile acid metabolism and the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2011, 11, 160–166. 10.1007/s11892-011-0187-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pols T. W.; Noriega L. G.; Nomura M.; Auwerx J.; Schoonjans K. The bile acid membrane receptor TGR5 as an emerging target in metabolism and inflammation. J. Hepatol. 2011, 54, 1263–1272. 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Lou G.; Meng Z.; Huang W. TGR5: A Novel Target for Weight Maintenance and Glucose Metabolism. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2011, 2011, 853501–853501. 10.1155/2011/853501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T.; Tanaka K.; Suzuki J.; Miyoshi H.; Harada N.; Nakamura T.; Miyamoto Y.; Kanatani A.; Tamai Y. Targeted disruption of G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 (Gpbar1/M-Bar) in mice. J. Endocrinol. 2006, 191, 197–205. 10.1677/joe.1.06546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassileva G.; Golovko A.; Markowitz L.; Abbondanzo S. J.; Zeng M.; Yang S.; Hoos L.; Tetzloff G.; Levitan D.; Murgolo N. J.; Keane K.; Davis H. R. Jr.; Hedrick J.; Gustafson E. L. Targeted deletion of Gpbar1 protects mice from cholesterol gallstone formation. Biochem. J. 2006, 398, 423–430. 10.1042/BJ20060537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuma S.; Hirasawa A.; Tsujimoto G. Bile acids promote glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through TGR5 in a murine enteroendocrine cell line STC-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 329, 386–390. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicciari R.; Gioiello A.; Macchiarulo A.; Thomas C.; Rosatelli E.; Natalini B.; Sardella R.; Pruzanski M.; Roda A.; Pastorini E.; Schoonjans K.; Auwerx J. Discovery of 6alpha-ethyl-23(S)-methylcholic acid (S-EMCA, INT-777) as a potent and selective agonist for the TGR5 receptor, a novel target for diabesity. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7958–7961. 10.1021/jm901390p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans K. A.; Budzik B. W.; Ross S. A.; Wisnoski D. D.; Jin J.; Rivero R. A.; Vimal M.; Szewczyk G. R.; Jayawickreme C.; Moncol D. L.; Rimele T. J.; Armour S. L.; Weaver S. P.; Griffin R. J.; Tadepalli S. M.; Jeune M. R.; Shearer T. W.; Chen Z. B.; Chen L.; Anderson D. L.; Becherer J. D.; De Los Frailes M.; Colilla F. J. Discovery of 3-aryl-4-isoxazolecarboxamides as TGR5 receptor agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7962–7965. 10.1021/jm901434t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert M. R.; Siegel D. L.; Staszewski L.; Cayanan C.; Banerjee U.; Dhamija S.; Anderson J.; Fan A.; Wang L.; Rix P.; Shiau A. K.; Rao T. S.; Noble S. A.; Heyman R. A.; Bischoff E.; Guha M.; Kabakibi A.; Pinkerton A. B. Synthesis and SAR of 2-aryl-3-aminomethylquinolines as agonists of the bile acid receptor TGR5. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 5718–5721. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budzik B. W.; Evans K. A.; Wisnoski D. D.; Jin J.; Rivero R. A.; Szewczyk G. R.; Jayawickreme C.; Moncol D. L.; Yu H. Synthesis and structure–activity relationships of a series of 3-aryl-4-isoxazolecarboxamides as a new class of TGR5 agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 1363–1367. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips D. P.; Gao W.; Yang Y.; Zhang G.; Lerario I. K.; Lau T. L.; Jiang J.; Wang X.; Nguyen D. G.; Bhat B. G.; Trotter C.; Sullivan H.; Welzel G.; Landry J.; Chen Y.; Joseph S. B.; Li C.; Gordon W. P.; Richmond W.; Johnson K.; Bretz A.; Bursulaya B.; Pan S.; McNamara P.; Seidel H. M. Discovery of trifluoromethyl-(pyrimidin-2-yl)azetidine-2-carboxamides as potent, orally bioavailable TGR5 (GPBAR1) agonists: Structure–activity relationships, lead optimization, and chronic in vivo efficacy. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 3263–3282. 10.1021/jm401731q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Q.; Duan H.; Ning M.; Liu J.; Feng Y.; Zhang L.; Zhu J.; Leng Y.; Shen J. 4-Benzofuranyloxynicotinamide derivatives are novel potent and orally available TGR5 agonists. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 82, 1–15. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H.; Ning M.; Chen X.; Zou Q.; Zhang L.; Feng Y.; Zhang L.; Leng Y.; Shen J. Design, synthesis and anti-diabetic activity of 4-phenoxynicotinamide and 4-phenoxypyrimidine-5-carboxamide derivatives as potent and orally efficacious TGR5 agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 10475–10489. 10.1021/jm301071h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski D. W.; Futatsugi K.; Warmus J. S.; Orr S. T. M.; Freeman-Cook K. D.; Londregan A. T.; Wei L.; Jennings S. M.; Herr M.; Coffey S. B.; Jiao W.; Storer G.; Hepworth D.; Wang J.; Lavergne S. Y.; Chin J. E.; Hadcock J. R.; Brenner M. B.; Wolford A. C.; Janssen A. M.; Roush N. S.; Buxton J.; Hinchey T.; Kalgutkar A. S.; Sharma R.; Flynn D. A. Identification of Tetrahydropyrido[4,3-d]pyrimidine Amides as a New Class of Orally Bioavailable TGR5 Agonists. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 63–68. 10.1021/ml300277t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futatsugi K.; Bahnck K. B.; Brenner M. B.; Buxton J.; Chin J. E.; Coffey S. B.; Dubins J.; Flynn D.; Gautreau D.; Guzman-Perez A.; Hadcock J. R.; Hepworth D.; Herr M.; Hinchey T.; Janssen A. M.; Jennings S. M.; Jiao W.; Lavergne S. Y.; Li B.; Li M.; Munchhof M. J.; Orr S. T. M.; Piotrowski D. W.; Roush N. S.; Sammons M.; Stevens B. D.; Storer G.; Wang J.; Warmus J. S.; Wei L.; Wolford A. C. Optimization of triazole-based TGR5 agonists towards orally available agents. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 205–210. 10.1039/C2MD20174G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H.; Ning M.; Zou Q.; Ye Y.; Feng Y.; Zhang L.; Leng Y.; Shen J. Discovery of Intestinal Targeted TGR5 Agonists for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 3315–3328. 10.1021/jm500829b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S.; Patil A.; Aware U.; Deshmukh P.; Darji B.; Sasane S.; Sairam K.V. V. M; Priyadarsiny P.; Giri P.; Patel H.; Giri S.; Jain M.; Desai R. C. Discovery of a Potent and Orally Efficacious TGR5 Receptor Agonist. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 51–55. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Sui Z.; Kauffman J.; Hou C.; Chen C.; Du F.; Kirchner T.; Liang Y.; Johnson D.; Murray V. W.; Demarest K. Evaluation of Anti-diabetic Effect and Gall Bladder Function with 2-Thio-5-Thiomethyl Substituted Imidazoles as TGR5 Receptor Agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 1760–1764. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.02.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.