Abstract

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL), also known as kala-azar, is a life-threatening systemic disease caused by the obligate intracellular protozoan, Leishmania, and transmitted to humans by the female phlebotomine sand fly (Phlebotomus argentipes). The disease is fatal, if left untreated. We report a case of a patient clinically suspected of disseminated tuberculosis, but fine needle aspiration cytology of cervical and axillary lymph nodes yielded a diagnosis of leishmaniasis. Diagnosis of VL was challenging as the disease closely mimicked tuberculosis in the setting of extensive lymphadenopathy including conglomerate of mesenteric lymph nodes, on and off fever, and granulomatous lymphadenitis on aspiration. Bone marrow examination was further performed. A detailed workup revealed patient to be severely immunocompromised and newly diagnosed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive. Worldwide, India has the largest number of VL cases, accounting for 40%–50% of world's disease burden and the second largest HIV-infected population, accounting for approximately 10% of the global disease burden. HIV increases the risk of developing VL by 100–2320 times in endemic areas and concurrently VL promotes the clinical progression of HIV disease. Co-infection with HIV alters the body's immune response to leishmaniasis thus leading to unusual presentations. This case highlights the diagnostic problem in the aforesaid setting. Moreover, co-infection with HIV in VL can be a potential source of drug resistance. An early diagnosis and intensified treatment is the key to patient management.

Keywords: Co-infection, human immunodeficiency virus, lymph node, visceral leishmaniasis

INTRODUCTION

Human visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a potentially fatal parasitic infection caused by hematogenous dissemination of amastigote forms of Leishmania species. Demonstration of these parasites in the bone marrow aspirate is a sensitive modality for diagnosis. However, primary diagnosis of VL in an otherwise unsuspected case on lymph node aspirate has seldom been reported. We hereby discuss one such unusual case.

CASE REPORT

A 42-year-old male presented to the medical emergency department with complaints of weakness and significant weight loss over 1 year. He had episodes of low-grade fever in the past year, for which the patient was treated for pulmonary tuberculosis 2 years back. At present, he was again put on antitubercular therapy (ATT) for the past 1 month; however, no improvement was noted and hence the patient was referred to our hospital. There was no significant family history. On general physical examination, the patient was found to be thin built, pale, and afebrile with abdominal distension. Left submandibular and left axillary lymph nodes were enlarged and measured 1.5 cm in diameter. Mild hepatosplenomegaly was noted, however no fluid thrill could be discerned. Ultrasound abdomen revealed enlarged multiple conglomerate of mesenteric lymph nodes with the largest node measuring 22 mm × 18 mm. Clinical chemistry revealed A:G reversal with total protein of 9.5 g%, albumin of 2.0 g%, globulin of 7.5 g%, and A:G ratio of 1:3.75. Other parameters of liver function test and kidney function test were found to be within normal limits. Complete hemogram revealed pancytopenia with hemoglobin: 6 g%, total leukocyte count: 1800/μL, differential leukocyte count: polymorphs 47%, lymphocytes 51%, eosinophils 1%, monocytes 1%, platelets: 48,000/μL, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 50 mm/h. Peripheral smear revealed the presence of rouleaux; however, no hemoparasite was noted.

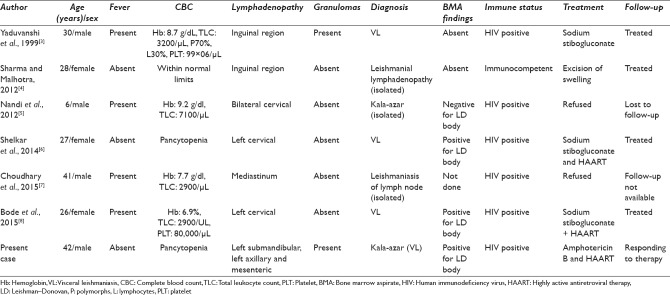

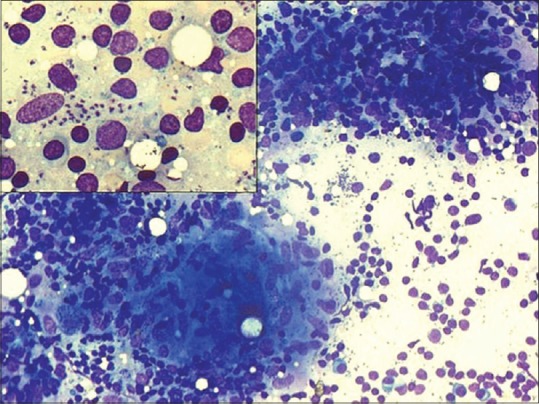

Fine needle aspiration cytology was performed on the left submandibular and axillary lymph nodes, which yielded thick aspirate. Smears prepared showed few epithelioid cell granulomas interspersed with discrete and aggregates of histiocytes in a background of reactive lymphoid cells and many plasma cells. Numerous intracellular as well as extracellular amastigote forms of Leishmania species were seen [Figure 1]. In view of strong clinical suspicion, Ziehl–Neelsen staining for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) was also done which came out to be negative. Both polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis and AFB culture yielded negative result. Later on, rK39 antigen was also found to be positive. Bone marrow examination (both aspirate and biopsy) revealed a prominence of plasma cells and histiocytes along with infiltration by numerous intracellular as well as extracellular amastigote forms of Leishmania spp. Average parasite density (APD) of 5+, i.e., 10–100 Leishman–Donovan (LD) bodies/field, was noted in the bone marrow aspirate (BMA) [Figure 2]. In view of high APD, the patient's human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status was evaluated which showed positive serology. Immune status evaluation revealed a low CD4 count; 28/μL (reference range: 400–1600/μL). The patient was started on intravenous amphotericin B along with highly active antiretroviral therapy. Improvement was noted after 14 days of treatment (CD4 count: 36/μL). Subsequent bone marrow evaluations revealed a significant fall in APD and clinical improvement in patient's health; weight gain, improved appetite, and rise in CD4 counts.

Figure 1.

Lymph node aspirate with scattered epithelioid cell granuloma (Giemsa, ×20). Inset: Numerous intracellular as well as extracellular Leishman–Donovan bodies (Giemsa, ×40)

Figure 2.

Bone marrow aspirate: Histiocytes showing numerous intracellular Leishman–Donovan bodies. Scattered extracellular Leishman–Donovan bodies (Giemsa, ×100); Inset: (a) Megakaryocyte surrounded with Leishman–Donovan bodies (Giemsa ×20) (b) Bone marrow biopsy showing histiocytes containing Leishman–Donovan bodies (H and E, ×40)

DISCUSSION

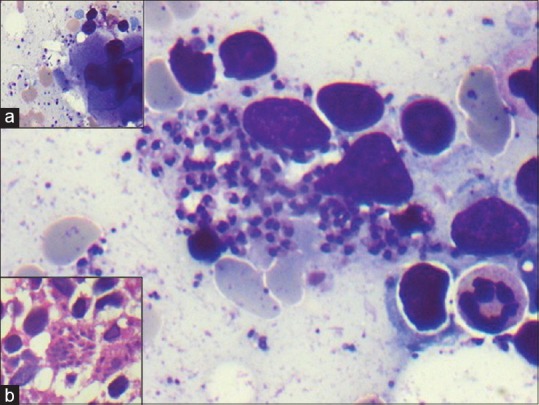

Kala-azar is known to be endemic in the North Indian state of Bihar; however, the cases have now crossed geographical boundaries and have been reported in several other states, probably due to migrant labor population.[1] Presentation of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) ranges from double-peak fever, wasting, weight loss, hepatomegaly with pancytopenia, and splenomegaly to completely asymptomatic infection.[2] Peripheral lymphadenopathy due to kala-azar is rare in India with only a few reported cases where a primary diagnosis has been made on fine needle aspiration of peripheral lymph nodes [Table 1].[3,4,5,6,7,8]

Table 1.

Visceral leishmaniasis cases diagnosed on lymph node aspiration in India

Lymph node aspiration (LNA) is an uncommon modality for the diagnosis of VL. The commonly used method for diagnosing VL has been the demonstration of parasites in bone marrow splenic aspirate. On literature search, only six cases of Indian VL cases diagnosed on lymph node were found. Similar to our index case, two of the reported cases were afebrile at the time of diagnosis while rest had the classical double-peak fever. Cervical lymphadenopathy was present in three of the six cases, which was also noted in our case. In addition, a rare finding of conglomerate of enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes was noted in our case which has not been reported so far in the previously reported cases. Granulomatous inflammation of lymph node is commonly seen in tuberculosis but has been observed very less often in VL cases. Granulomas were noted in our case similar to Yaduvanshi et al.[3] However, their patient had a shorter duration of symptoms and had opportunistic infections such as oral thrush and herpes at the time of presentation. LD bodies were absent in the bone marrow of their patient contrary to the index case where bone marrow examination revealed heavy parasite load. The patient of Yaduvanshi et al.[3] showed a rapid improvement with intramuscular sodium stibogluconate; on the contrary, our patient received a prolonged intensified treatment of Liposomal amphotericin B to achieve remission. Five out of the six reported cases including the present case tested positive for HIV, highlighting a strong link between the two diseases.

Immune response to Leishmania infection is T-cell mediated, and Leishmania ensures its own survival by modulating host immune system. Patients with active VL display an impaired Th1 response and an increased Th2-mediated response.[9] HIV–VL co-infection is a complex chronic disease. HIV/leishmaniasis co-infection causes suppression of cell-mediated immunity leading to atypical dissemination of disease to skin and reticuloendothelial system. The presence of both pathogens concomitantly in the same host cell (the macrophage) has enhanced reciprocal effects that influence the expression and multiplication of either one or both pathogens. Diagnosis of VL in these patients is often challenging, in view of the absence of classical clinical presentation, early mortality, drug toxicity, resistance, and poor prognosis vis-a-vis that in VL alone.[10] This will help chalk out long-term management strategy for an effective treatment of these patients.

SUMMARY

The present case highlights the diagnostic problem as the clinical presentation mimicked disseminated tuberculosis very closely. Multiple lymph node enlargements including mesenteric lymphadenopathy are very uncommon in Indian VL. A history of ATT intake, weight loss, intermittent fever, high ESR, and multiple peripheral as well as mesenteric lymphadenopathies are highly suggestive of tuberculosis on clinical ground. Even fine needle aspiration revealed granulomatous inflammation. However, LD bodies were demonstrated in the LNAs, which confirmed the diagnosis of VL. In addition, this case also brings forth the role of HIV co-infection in the modulation of classical presentations. A high degree of awareness is needed to clinch the diagnosis, particularly in HIV-positive patients, as an early intervention is important for better patient management, and to prevent relapse and drug resistance.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

Poojan Agarwal and Manju Kaushal were involved in conceptualization of the study. Vijay Kumar and Poojan Agarwal were involved in writing and formatting of the study. Manju Kumari and Arvind Chaudhary were involved in data collection. This study has not been previously published anywhere.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The study was conducted after taking informed patient consent and within all standards.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

AFB - Acid fast bacilli

ATT - Antitubercular therapy

ESR - Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

FNAC - Fine needle aspiration cytology

HIV - Human immunodeficiency virus

LD body - Leishman Donovan body

LNA - Lymphnode aspirate

VL - Visceral leishmaniasis.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Contributor Information

Poojan Agarwal, Email: poojanagarwal@gmail.com.

Vijay Kumar, Email: vijaypgi1@gmail.com.

Manju Kaushal, Email: manju_kaushal@yahoo.com.

Manju Kumari, Email: manju.yadav126@gmail.com.

Arvind Chaudhary, Email: arvindchaudhary59@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Is the Alarm Justified? India Environment Portal Knowledge for Change. 1999. [Last cited on 2016 Jun 23]. Available from: http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/content/20539/is-the-alarm-justified .

- 2.Chappuis F, Sundar S, Hailu A, Ghalib H, Rijal S, Peeling RW, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis: What are the needs for diagnosis, treatment and control? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:873–82. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaduvanshi A, Jain M, Jain SK, Jain S, Arora S. Visceral leishmaniasis masquerading as tuberculosis in a patient with AIDS. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:732–4. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.75.890.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma M, Malhotra A. Isolated leishmanial lymphadenopathy - A rare type of leishmaniasis in India: A case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:1002–4. doi: 10.1002/dc.21694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nandi M, Sarkar S, Mondal R. Kala-azar presenting as isolated cervical lymphadenopathy in an HIV-infected child. S Afr J Child Health. 2012;6:88–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shelkar R, Ekhar V, Anand A, Rane S, Ghorpade R. Mucosal leishmaniasis a rare entity. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2014;3:3614–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choudhary NS, Kataria S, Guleria M, Puri R. Leishmaniasis presenting as small isolated mediastinal lymphadenopathy diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Endoscopy. 2015;47(Suppl 1):E147–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bode AN, Poflee SV, Pande NP, Umap PS. Leishmaniasis in a patient with HIV co-infection: Diagnosis on fine needle aspiration cytology. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2015;58:563–5. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.169020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ezra N, Ochoa MT, Craft N. Human immunodeficiency virus and leishmaniasis. J Glob Infect Dis. 2010;2:248–57. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.68528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burza S, Mahajan R, Sinha PK, van Griensven J, Pandey K, Lima MA, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis and HIV co-infection in Bihar, India: Long-term effectiveness and treatment outcomes with liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]